Abstract

Ameloblastoma is a locally invasive benign neoplasm derived from odontogenic epithelium and presents with diverse phenotypes yet to be characterized molecularly. High recurrence rates of 50–80% with conservative treatment in some sub-types warrants radical surgical resections resulting in high morbidity. The objective of the study was to characterize the transcriptome of ameloblastoma and identify relevant genes and molecular pathways using normal odontogenic tissue (human “dentome”) for comparison. Laser capture microdissection was used to obtain neoplastic epithelial tissue from 17 tumors which were examined using the Agilent 44 k whole genome microarray. Ameloblastoma separated into 2 distinct molecular clusters that were associated with pre-secretory ameloblast and odontoblast. Within the pre-secretory cluster, 9/10 of samples were of the follicular type while 6/7 of the samples in the odontoblast cluster were of the plexiform type (p < 0.05). Common pathways altered in both clusters included cell-cycle regulation, inflammatory and MAPkinase pathways, specifically known cancer-driving genes such as TP53 and members of the MAPkinase pathways. The pre-secretory ameloblast cluster exhibited higher activation of inflammatory pathways while the odontoblast cluster showed greater disturbances in transcription regulators. Our results are suggestive of underlying inter-tumor molecular heterogeneity of ameloblastoma sub-types and have implications for the use of tailored treatment.

Ameloblastoma is a slow-growing, locally invasive, benign epithelial odontogenic neoplasm. It is thought to be arise from SOX2-expressing dental lamina epithelium1, remnants of the tooth-forming enamel organ2. The tumor exhibits epithelial cells resembling pre-ameloblasts on a basement membrane in loosely arranged cells resembling stellate reticulum while the stroma consists of loose connective tissue. Although odontogenic tumors are relatively rare, they constitute 3.8% of head and neck pathology, of which 40–50% are ameloblastoma3,4. Occasionally, ameloblastomas show malignant features or transform into malignancy5 and in rare cases metastasize6. Current treatment modalities range from conservative enucleation to radical excision and vary according to tumor subtype and location7,8. High recurrence rates (50–80%) have been observed in cases of conservative treatment9. Consequently, and despite recent advances in imaging-assisted surgical margin localization, post-operative histological confirmation is still required. This forces surgeons to either act conservatively, risking the need for a second surgery, or act aggressively thus increasing morbidity10 and the need for extensive reconstructive surgery.

There are few genomics and transcriptomics studies of ameloblastoma, with most investigations focusing on candidate-genes. Moreover, different comparison tissues were used in the handful of microarray studies; including gingival tissue11,12, whole tooth buds13, dentigerous cysts14 and a universal human reference RNA15. Furthermore, whole tumor samples used in these studies included large portions of stromal tissue. In spite of the heterogeneity in comparison tissue, there have been advances in understanding tumorigenesis of ameloblastoma.

A recent study examining the whole transcriptome of ameloblastoma suggested the existence of distinct molecular subtypes12. It is envisaged that better understanding of the molecular basis of ameloblastoma can aid the identification of diagnostic and prognostic markers and may lead to the development of novel, personalized treatment protocols16. To address this knowledge gap, we embarked on this study aiming to characterize the transcriptome of neoplastic ameloblastoma tissue and identify relevant molecular pathways and genes, using whole genome microarray.

Methods

Tumor collection and preparation

The study was conducted in accordance with approved human subject research guidelines and was approved by the local institutional review board and the ethics committee of the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. Between 2005 and 2008, 2 fresh frozen samples were obtained during surgical resection and 15 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples were retrieved from the archives of the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology Laboratory, University of North Carolina (UNC) School of Dentistry. All samples were evaluated by a board-certified oral and maxillofacial pathologist and at least one other author and diagnoses were classified based on the 2005 WHO Histologic Classification of Odontogenic Tumors. Additional demographic data including gender, age, race, and tumor recurrence were recorded and examined for potential associations.

The fresh tumors including the bony resected margins were placed in RNAlater and Richard Allan Scientifics’ decalcifying solution (water, hydrochloric acid, EDTA, tetrasodium tartrate and potassium tartrate) at 4 °C for 1–4 weeks. They were then frozen at −80 °C before 7 μm sections were obtained under RNAse-free conditions15, stained lightly with hematoxylin & eosin and sent for immediate laser capture microdissection (LCM). The FFPE blocks were decalcified before embedding in paraffin. The samples were sectioned, stained and sent for laser capture.

Laser capture microdissection

The AutoPixTM automated LCM system (Arcturus Engineering, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to isolate tumor cells (basal epithelial cells adjacent to the basement membrane). Images of the tissue sections including the captured regions were obtained before and after LCM.

RNA extraction and microarray

Laser-captured cells from each tumor were pooled and total RNA was isolated with the PicoPure RNA Isolation kit (Arcturus Bioscience, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was used to assess the yield and quality of total RNA. Amplification was completed on all samples using TargetAmpTM 2-Round Aminoallyl-aRNA Amplification Kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI, USA).

RNA was then analyzed using the Agilent Whole Human Genome Microarray 4 × 44 K G4112F (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) containing 44 thousand 60-mer oligonucleotides representing over 41 thousand human gene transcripts. For this step, 200 ng of RNA was converted into labeled cRNA with nucleotides coupled to fluorescent dye Cy3 using the Low RNA Input Linear Amplification Kit (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The Human Universal Reference RNA from Stratagene (Santa Clara, CA, USA) was coupled with Cy5. Cy3-labeled cRNA (1.65 ng) from each sample and the Cy5-labeled universal reference was hybridized to the Agilent whole genome array 41 k formatted chips. Data were extracted using Feature Extraction version 9.5 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Background subtraction and Loess normalization were performed using default setting of the Agilent extractor. The use of the universal RNA facilitated the use of the dentome as a comparison. It acts as a technical intra/inter normalizing control, decreasing variability by measuring signal output ratio of experimental to reference RNA rather than relying on absolute signal intensity two-color hybridization experiments17. The dentome consists of odontogenic tissue (microdissected samples of human odontoblasts, pre-secretory ameloblasts and secretory ameloblasts) expression data from previous work that employed the universal reference as a normalizing control18. The data set included 4 samples of each type of odontogenic tissue. It was collected from 12 anterior tooth buds (incisor and canine) from 4 different fetuses with each fetus contributing 3 tooth buds. Each type of odontogenic tissue was collected from a single tooth bud with each of the 3 buds providing a single type of odontogenic tissue or developmental stage. (Gene Expression Omnibus microarray database accession number GSE63289). The ameloblastoma expression data were submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus microarray database (accession number GSE68531).

Microarray data analysis

A multiclass analysis was conducted between the 3 types of odontogenic tissue and the 60 genes differentially expressed at a false discovery rate (FDR) <20% were designated as the odontogenic tissue-defining genes. The most appropriate comparison tissue was decided to be the normal tissue with the most similar profile to ameloblastoma, such that identified differences would be tumor specific. Cluster analysis was conducted using Cluster 3.0 between the 3 normal and tumor samples and visualized using Java TreeView-1.1.6r2.

Differential gene expression between tumors and comparison tissue were examined using Significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) 4.0. Ingenuity pathway analysis was used to identify differentially expressed pathways. In addition, upstream analysis from the ingenuity pathway analysis software was conducted. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)19 was conducted using GSEA v2.1.0 from the Broad institute (Cambridge, MA, USA) and the “all curated gene sets v4.0” available via the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB)20. Additionally, the ameloblastoma transcriptome was compared with the 13 cancer molecular subtypes from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project21 to investigate possible correlation with other known cancer types.

Microarray gene expression validation using NanoString

A variety of approaches have been used to validate microarray data in the literature and NanoString was selected for the study. A random subset of 3 ameloblastoma and 2 control odontogenic tissue samples was used to validate the microarray gene expression data. NanoString nCounter (Seattle, WA, USA) high throughput gene expression analysis22 was performed using the Human Cancer Reference codeset (http://www.nanostring.com/products/gene_expression_panels). Each reaction contained 50 ng of total sample RNA plus reporter and capture probes. Digital counts were extracted, normalized and analyzed using nSolver v2.5 software. Differential expression between ameloblastoma and pre-secretory ameloblast from nanoString was compared with that obtained from the microarray.

Results

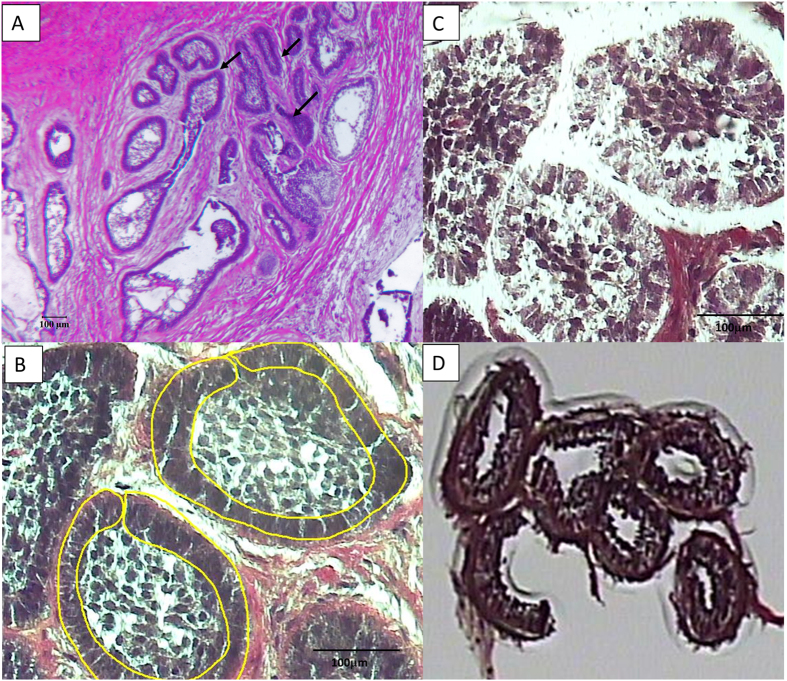

LCM facilitated the isolation of basal epithelial (neoplastic) cells from the tumor samples (Fig. 1) without contamination from surrounding stroma cells. RNA was extracted from the LCM samples, with the 260/280 ratio for the 17 samples between 1.7–2.5 and a yield of between 88ng to 928ng (Supplemental Table 1). Quality control analysis conducted on the microarray chips indicated expected values for positive and negative controls, as well as uniformly high detected genes in both the red and green channels. Overall, no outliers were detected in either the normal tissue or tumor arrays indicating consistency in hybridization between samples.

Figure 1. The micrographs show the laser capture of the epithelial portion of an ameloblastoma sample.

(A) – light micrograph of follicular ameloblastoma at 4X showing tumor epithelial follicles that are single-cell thick with surrounding stroma. Arrows points to tumor follicles, (B) – light micrograph of follicular ameloblastoma at 20X showing the laser capture outline of epithelial cells, (C) – remnants of the stroma tissue after LCM and (D) – captured cells on capsure cap. Scale bar: 100 μm.

NanoString validation

Due to the limited RNA quantity available, we did not conduct qPCR validation; instead, the NanoString platform was used to validate microarray gene expression data. Fold changes obtained with the nCounter system were correlated with those obtained from the microarray for the same samples (Supplementary Table 2). The 2 sets of expression data showed a good Pearson correlation (r = 0.61) in the scatter-plot (Supplementary Fig. 1).

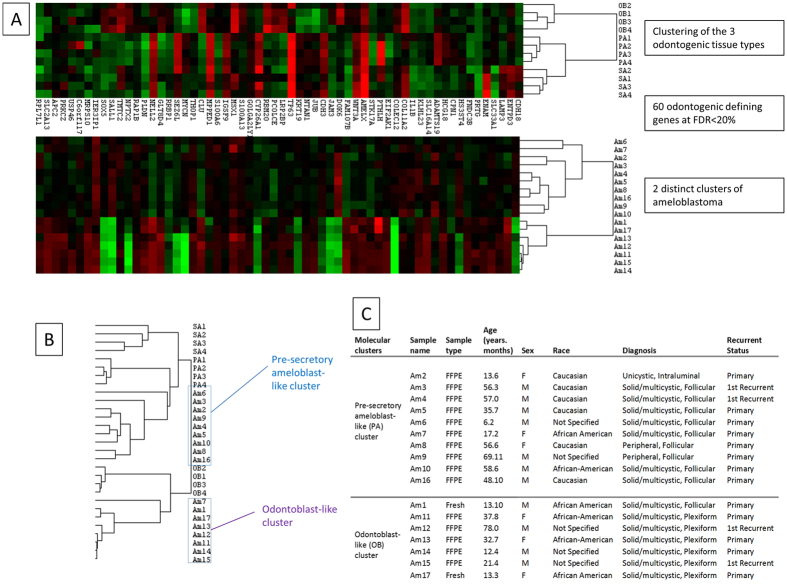

Determination of comparison tissue

Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted for the tumor and normal tissue samples which showed the presence of 2 distinct clusters of ameloblastoma and a separate cluster of normal odontogenic tissue (Supplementary Fig. 2). Supervised cluster analysis using the 60 odontogenic tissue defining genes showed that the 2 clusters of ameloblastoma associated most closely with pre-secretory ameloblast (PA) and odontoblast (OB) (Fig. 2A,B). As such, these 2 clusters were designated as the pre-secretory ameloblast-like ameloblastoma (pAM) and odontoblast-like ameloblastoma (oAM), respectively. Out of 10 samples in the pAM cluster, 9 were of the follicular type while 6/7 of the samples in the oAM cluster were of the plexiform type. (Fig. 2C). A Chi-Square analysis showed that the molecular clusters were significantly associated with a histological subtype (p < 0.05). A single comparison tissue could not be designated as the 2 clusters associated most closely with different odontogenic tissue; instead, a multiclass approach was employed.

Figure 2. Cluster analysis used to determine reference tissue.

(A) – Heat map of the 3 different odontogenic tissues (OB – Odontoblast, PA – Pre-secretory ameloblast, SA – Secretory ameloblast) and the 2 distinct clusters of Ameloblastoma (AM) clustered using the 60 odontogenic epithelium-defining genes. (B) – Array tree showing grouping of the 2 clusters with odontoblast and pre-secretory ameloblast. (C) – Participant demographic and tumor phenotype.

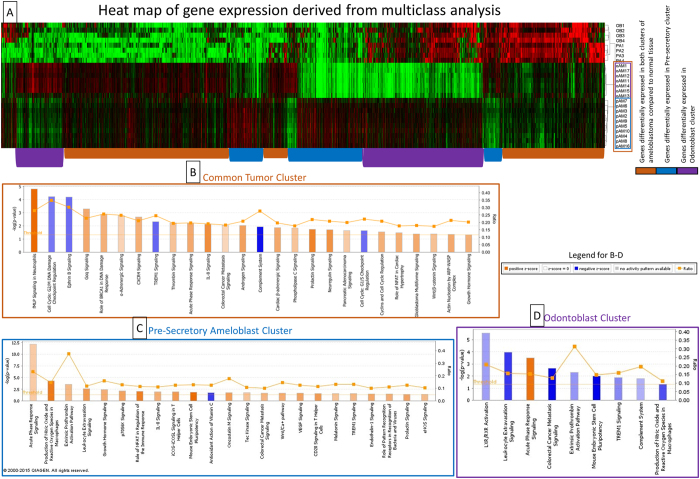

Multiclass analysis

Multiclass analysis was conducted between the 2 tumor clusters and 2 associated normal tissues (pAM, oAM, PA, OB) and differentially expressed genes were carried forward in a cluster analysis (Fig. 3A). To characterize the transcriptome of ameloblastoma and the 2 molecular sub-clusters, the gene expression data were analyzed in 3 groups. The common tumor cluster describes differential gene expression common in both tumor clusters compared to normal tissue and comprises 2592 genes that were expressed at a higher and lower level in the 2 tumor clusters (pAM, oAM) compared to the 2 normal tissue clusters (OB, PA). The pAM cluster describes differential gene expression unique to that cluster and consists of 1287 genes expressed at higher and lower levels compared to the other 3 groups. The oAM cluster describes differential gene expression unique to oAM tumors and consists of 1516 genes expressed at a higher and lower levels compared to the other 3 groups. The genes with fold changes at FDR < 1% were used for pathway analysis (Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 3. Multiclass and pathway analysis of the different tumor clusters.

(A) – Heat map of the genes with a FDR < 1% that are differentially expressed in the 4 clusters (OB – odontoblast, PA – pre-Secretory Ameloblast, oAM – odontoblast-like ameloblastoma, pAM – pre-secretory Ameloblast-like ameloblastoma) from a SAM multiclass analysis. The cluster tree on the right shows the 2 distinct clusters of ameloblastoma. Groups of genes with similar expression (identified by colored bars at the bottom of the heat map) were used for pathway analysis for the different clusters of ameloblastoma which were shown in (B–D). (B) – Canonical pathways that are differentially expressed for the Common tumor cluster in IPA. (C) – Canonical pathways that are differentially expressed for the Pre-secretory ameloblast cluster in IPA. (D) – Canonical pathways that are differentially expressed for the odontoblast cluster in IPA.

Pathway and gene set enrichment analysis

Ingenuity pathway analysis was used to examine the activated and inhibited canonical pathways for each tumor cluster (Table 1).

Table 1. Canonical pathways differentially expressed in ameloblastoma clusters.

| Canonical pathways different between the ameloblastoma common tumor cluster and normal cells | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological process | Ingenuity Canonical Pathways | −log(p-value*) | Ratio | z-score |

| Inflammatory (Immune) response/cytokine signaling | fMLP Signaling in Neutrophils | 4.81 | 0.28 | 3.674 |

| CXCR4 Signaling | 2.68 | 0.21 | 1.961 | |

| TREM1 Signaling | 2.34 | 0.25 | −1.213 | |

| Thrombin Signaling | 2.21 | 0.19 | 1.512 | |

| Acute Phase Response Signaling | 2.20 | 0.20 | 2.117 | |

| IL-8 Signaling | 2.12 | 0.19 | 2.785 | |

| Complement System | 1.94 | 0.28 | −1.89 | |

| Cell cycle regulation | Cell Cycle: G2/M DNA Damage Checkpoint Regulation | 4.23 | 0.35 | −1.069 |

| Role of BRCA1 in DNA Damage Response | 2.88 | 0.26 | 1.941 | |

| Cell Cycle: G1/S Checkpoint Regulation | 1.63 | 0.22 | −1.155 | |

| Cyclins and Cell Cycle Regulation | 1.53 | 0.21 | 1.941 | |

| Cancer | Colorectal Cancer Metastasis Signaling | 2.04 | 0.18 | 1 |

| Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Signaling | 1.63 | 0.20 | 1.291 | |

| Glioblastoma Multiforme Signaling | 1.40 | 0.18 | 2.132 | |

| Wnt/β-catenin Signaling | 1.37 | 0.18 | 1.528 | |

| Actin Nucleation by ARP-WASP Complex | 1.35 | 0.21 | 2.111 | |

| Map kinase related | Gαq Signaling | 3.31 | 0.23 | 2.117 |

| α-Adrenergic Signaling | 2.77 | 0.25 | 1.069 | |

| Phospholipase C Signaling | 1.83 | 0.18 | 1.461 | |

| Prolactin Signaling | 1.74 | 0.22 | 3.051 | |

| Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) | Ephrin B Signaling | 4.21 | 0.30 | −1.155 |

| Neuregulin Signaling | 1.69 | 0.21 | 2.668 | |

| Nuclear receptor signaling | Androgen Signaling | 2.01 | 0.21 | 2.333 |

| Cellular growth and proliferation | Growth Hormone Signaling | 1.32 | 0.20 | 1.941 |

| Others | Cardiac β-adrenergic Signaling | 1.87 | 0.20 | 2.138 |

| Role of NFAT in Cardiac Hypertrophy | 1.47 | 0.18 | 1.961 | |

| Canonical pathways different for the ameloblastoma presecretory cluster | ||||

| Inflammatory (Immune) response/cytokine signaling | Acute Phase Response Signaling | 12.20 | 0.23 | 1.225 |

| Production of Nitric Oxide and Reactive Oxygen Species in Macrophages | 4.26 | 0.15 | 3.138 | |

| Extrinsic Prothrombin Activation Pathway | 3.55 | 0.38 | 1.633 | |

| Leukocyte Extravasation Signaling | 2.63 | 0.12 | 2.324 | |

| Role of NFAT in Regulation of the Immune Response | 2.08 | 0.11 | 3 | |

| IL-8 Signaling | 1.95 | 0.11 | 1.886 | |

| iCOS-iCOSL Signaling in T Helper Cells | 1.91 | 0.13 | 2.333 | |

| Antioxidant Action of Vitamin C | 1.80 | 0.13 | −1.897 | |

| CD28 Signaling in T Helper Cells | 1.60 | 0.12 | 2.333 | |

| TREM1 Signaling | 1.55 | 0.13 | 1.667 | |

| Role of Pattern Recognition Receptors in Recognition of Bacteria and Viruses | 1.44 | 0.11 | 1.897 | |

| eNOS Signaling | 1.35 | 0.10 | 1.604 | |

| Cellular growth and proliferation | Growth Hormone Signaling | 2.44 | 0.16 | 1.897 |

| p70S6K Signaling | 2.15 | 0.13 | 2.138 | |

| Mouse Embryonic Stem Cell Pluripotency | 1.84 | 0.13 | 3.464 | |

| Oncostatin M Signaling | 1.75 | 0.18 | 2.236 | |

| VEGF Signaling | 1.63 | 0.12 | 2.121 | |

| Protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) | Tec Kinase Signaling | 1.73 | 0.11 | 1.387 |

| Cancer | Colorectal Cancer Metastasis Signaling | 1.71 | 0.10 | 1.706 |

| Wnt/Ca+ pathway | 1.68 | 0.15 | 1.89 | |

| Others | Melatonin Signaling | 1.59 | 0.13 | 1.414 |

| Endothelin-1 Signaling | 1.45 | 0.10 | 2 | |

| Prolactin Signaling | 1.41 | 0.12 | 2.121 | |

| Canonical pathways different for the ameloblastoma odontoblast cluster | ||||

| Inflammatory (Immune) response/cytokine signaling | Leukocyte Extravasation Signaling | 3.99 | 0.16 | −2.524 |

| Acute Phase Response Signaling | 3.51 | 0.16 | 1.897 | |

| Extrinsic Prothrombin Activation Pathway | 2.30 | 0.31 | −1.342 | |

| TREM1 Signaling | 1.89 | 0.16 | −1.508 | |

| Complement System | 1.80 | 0.19 | −1 | |

| Production of Nitric Oxide and Reactive Oxygen Species in Macrophages | 1.33 | 0.11 | −2.236 | |

| Nuclear receptor signaling | LXR/RXR Activation | 5.57 | 0.21 | −1.225 |

| Cancer | Colorectal Cancer Metastasis Signaling | 2.67 | 0.13 | −3.157 |

| Cellular growth and proliferation | Mouse Embryonic Stem Cell Pluripotency | 2.01 | 0.15 | −3.207 |

*p-value < 0.05.

The common tumor cluster had 21 activated (z-score > 1) and 5 inhibited (z-score < −1) pathways (Fig. 3B) at p-value < 0.05. Genes associated with notable biological processes that were differentially expressed in all the ameloblastoma tumors included prevention of damage to cell cycle regulation, cancer pathways, inflammatory pathways and Map kinase related pathways.

In addition, GSEA conducted between the common tumor cluster and normal tissues showed that 1860 out of the 2381 genes sets in the “all curated gene sets v4.0” were up-regulated in the common tumor cluster. Nineteen upregulated gene sets were significantly enriched at the nominal p-value < 0.05. (Supplementary Table 4).

The pre-secretory ameloblast tumor cluster had 22 activated and 1 inhibited pathway below the critical p-value threshold (Fig. 3C). Pathway analysis showed activation in the known cancer pathways, several inflammatory pathways and EGFR pathways.

The odontoblast tumor cluster had 1 activated and 8 inhibited pathways (Fig. 3D). Several inflammatory pathways were found to be inhibited in this cluster.

Upstream analysis

Upstream regulators that were predicted to be activated or inhibited are listed in Table 2. Most of the predicted upstream regulators in the common tumor cluster were transcription regulators, kinases and cytokines. Specifically, several Map kinase members and inflammatory cytokines were predicted to be activated.

Table 2. Upstream analysis using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis.

| Activated and inhibited molecules in Common Tumor Cluster | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecule Type | Upstream Regulator | Predicted Activation State | Activation z-score | p-value of overlap |

| transcription regulator | SOX11 | Inhibited | −2.16 | 0.47 |

| NUPR1 | Inhibited | −2.46 | 0.00 | |

| NEUROG1 | Inhibited | −2.18 | 0.00 | |

| KDM5B | Inhibited | −3.66 | 0.00 | |

| TP53 | Inhibited | −2.37 | 0.00 | |

| HIF1A | Activated | 2.90 | 0.00 | |

| JUN | Activated | 2.55 | 0.00 | |

| FOXM1 | Activated | 2.99 | 0.00 | |

| EZH2 | Activated | 2.06 | 0.10 | |

| YAP1 | Activated | 2.21 | 0.01 | |

| MYB | Activated | 2.39 | 0.00 | |

| kinase | TRIB3 | Inhibited | −2.00 | 0.10 |

| CDKN1A | Inhibited | −2.60 | 0.00 | |

| AKT1 | Activated | 2.65 | 0.01 | |

| EGFR | Activated | 2.20 | 0.04 | |

| MAPK9 | Activated | 2.31 | 0.02 | |

| PIM1 | Activated | 2.42 | 0.05 | |

| MAP3K14 | Activated | 2.21 | 0.13 | |

| EIF2AK2 | Activated | 2.43 | 0.01 | |

| ERBB2 | Activated | 2.46 | 0.00 | |

| cytokine | CSF2 | Activated | 2.43 | 0.01 |

| TNF | Activated | 2.27 | 0.00 | |

| IL1A | Activated | 2.12 | 0.00 | |

| IL6 | Activated | 3.33 | 0.01 | |

| OSM | Activated | 2.41 | 0.00 | |

| enzyme | STUB1 | Inhibited | −2.24 | 0.03 |

| HRAS | Activated | 2.16 | 0.00 | |

| ligand-dependent nuclear receptor | PGR | Activated | 3.22 | 0.00 |

| ESRRA | Activated | 2.20 | 0.07 | |

| transporter | SLC29A1 | Activated | 2.00 | 0.14 |

| S100A6 | Activated | 2.12 | 0.01 | |

| complex | IgG | Inhibited | −2.04 | 0.00 |

| NFkB (complex) | Activated | 2.35 | 0.00 | |

| Cg | Activated | 2.69 | 0.00 | |

| group | STAT5a/b | Activated | 2.00 | 0.55 |

| Mek | Activated | 2.36 | 0.05 | |

| Growth hormone | Activated | 2.55 | 0.06 | |

| transmembrane receptor | TREM1 | Activated | 2.82 | 0.00 |

| growth factor | NRG1 | Activated | 2.17 | 0.06 |

| other | RBM5 | Inhibited | −2.34 | 0.07 |

| UXT | Inhibited | −2.44 | 0.01 | |

| AHI1 | Activated | 2.00 | 0.24 | |

| RABL6 | Activated | 3.30 | 0.00 | |

| HSPB2 | Activated | 2.22 | 0.00 | |

| Activated and inhibited molecules in Presecretory Cluster | ||||

| enzyme | MGEA5 | Inhibited | −2.04 | 0.00 |

| ligand-dependent nuclear receptor | PPARG | Activated | 2.01 | 0.00 |

| transcription regulator | NUPR1 | Activated | 2.11 | 0.00 |

| growth factor | WISP2 | Activated | 2.24 | 0.06 |

| Activated and inhibited molecules in Odontoblast Cluster | ||||

| transcription regulator | SOX11 | Inhibited | −2.98 | 0.05 |

| MDM2 | Inhibited | −2.24 | 0.04 | |

| CEBPA | Inhibited | −2.14 | 0.00 | |

| NUPR1 | Inhibited | −2.47 | 0.36 | |

| TP53 | Inhibited | −2.19 | 0.01 | |

| enzyme | TGM2 | Inhibited | −3.59 | 0.00 |

| HMOX1 | Activated | 2.00 | 0.27 | |

| ligand-dependent nuclear receptor | AR | Inhibited | −2.24 | 0.25 |

| NR3C1 | Inhibited | −2.56 | 0.17 | |

| transporter | S100A6 | Activated | 2.45 | 0.01 |

| group | estrogen receptor | Inhibited | −2.28 | 0.00 |

Correlation with The Cancer Genome Atlas

The 2 molecular subtypes of ameloblastoma were compared with the transcriptome of the cancer subtypes in TCGA (Supplementary Fig. 3). The analysis did not show any significant correlation of ameloblastoma with any of the 13 subtypes of cancers that are well studied and has established treatment protocols. As ameloblastoma does not seem to correlate molecularly with the cancer subtypes, more investigation into ameloblastoma tumorigenesis is needed for the development of effective treatment.

Discussion

The major finding of this study was the molecular heterogeneity of ameloblastoma that was strongly associated with its histological subtypes. Gene expression profiles of follicular and plexiform subtypes were more closely related to gene expression profiles of different normal odontogenic tissues and the follicular subtype showed activation of different molecular pathways compared with the plexiform subtype. This new knowledge can serve as a rich hypothesis-generating resource for the study of molecular and phenotypic characteristics of ameloblastoma.

One of the strengths of this study was the use of LCM for the examination of odontogenic tumors. The ability of LCM to isolate one cell-thick discrete tissue populations23 facilitates the targeting and pooling of neoplastic epithelial portions of ameloblastoma. Similar to the present study, Heikinheimo and colleagues found that ameloblastoma gene expression is heterogeneous, and identified 2 distinct tumor clusters with gene expression profile that were most similar to gene expression in the cap/bell stage of tooth development12. Using supervised cluster analysis we found that more than half of ameloblastoma samples were most similar in gene expression to pre-secretory ameloblast, similar to those observed in the early cap/bell stage as described by Heikinheimo. The remaining ameloblastoma samples were associated with the mesenchymal-derived odontoblast rather than the epithelial-derived ameloblast; this appears to be driven by differences in inflammatory pathways and was associated with a different histological appearance. However, the early pre-secretory ameloblast in this sample could be more appropriately described as preameloblast from the early cap stage of tooth development. Preameloblasts share a number of genes with odontoblasts due to significant cross-talk during differentiation; it is therefore unsurprising that a cluster of ameloblastoma was associated with odontoblast.

The examination of pathways common to both tumors shows that inflammation appears to play an important role in ameloblastoma tumorigenesis and proliferation. This finding is similar to an earlier microarray study showing increased expression levels of inflammatory mediators13. Canonical pathway analysis showed that several immune/inflammatory pathways are activated in addition to several predicted activated upstream cytokines. The association between dysregulated inflammation and cancer progression has been studied extensively24. The greater number of pathways activated in the pre-secretory cluster suggests that this process may be more important in the follicular subtype.

The Wnt signaling pathway is important in the development of ameloblastoma as discussed in the microarray study by DeVilliers15. Some investigators found the activation of beta-catenin downstream of Wnt signaling25 while others found that expression of various Wnt pathways differ among ameloblastoma with the canonical Wnt pathway being the main transduction pathway26. In this study, the canonical Wnt/β-catenin Signaling pathway was found to be activated in the common tumor cluster, highlighting its importance in tumorigenesis.

Additionally, both tumor clusters revealed that damage to cell cycle regulation pathways play important roles. Alteration in cell cycle regulation has been found by other investigators examining ameloblastoma gene expression11,14. A key regulator in the cell cycle damage prevention pathways is TP53 which is also predicted to be inhibited in our upstream analysis. TP53 is a major tumor suppression gene27 and the loss of a tumor suppressor gene activity in ameloblastoma may be important in the tumorigenesis process. Although the dental epithelium defining SOX2 was not found to be differentially expressed, SOX11 of the same family of transcription factors related to oncogenic transformation28 was found to be inhibited in the tumor samples.

Several canonical pathways involving the MAPK pathways and upstream members were found to be activated in the common tumor cluster. The MAPK pathways have long been considered tumor driver pathways in the pathogenesis of various cancers and are thought to be important in ameloblastoma tumorigenesis29,30. Although the expression levels of usual targets such as BRAF and EGFR were not directly increased, activation of the pathway suggests alterations in the activity of the members. Recently, Kurppa and colleagues found BRAF gene mutations, specifically V600E mutation, in 63% of ameloblastomas31. BRAF is in the RAS pathway and MAPK cascade. This mutation leads to a 500 fold increase in activity of BRAF and increases signals through MEK to activate ERK32. ERK is the activator of numerous downstream transcription factors which induces biochemical functions such as cell differentiation, proliferation, growth, and apoptosis. The V600E mutation in BRAF is a promising oncogene target for the anti-neoplastic drug dabrafenib; which was used in conjunction with a MEK inhibitor in a patient with stage 4 ameloblastoma with good results33. The use of chemotherapeutic agents to reduce tumor size can be very helpful in cases of ameloblastoma requiring extensive surgical margins and major post-surgical reconstruction34.

In GSEA, the gene sets with the highest activation scores, were cancer related including “SMID_BREAST_CANCER_LUMINAL_A_DN”. Cancer related pathways were also found to be differentially expressed in our pathway analysis. Moreover, breast cancer specific “Role of BRCA1 in DNA Damage Response” pathway was found to be differentially expressed, with the 2 different analyses highlighting similar molecular pathways.

One of the short-comings of this study is that most of the samples were FFPE. Formalin fixing can cause the degradation of RNA35 and affect the accuracy of microarrays. However, recent studies supported the use of such samples for gene expression analysis36 and NanoString has been shown to produce consistent results independent of the sample type (fresh frozen versus FFPE)37. Genes in our microarray data that had the greatest fold changes showed good correlation with the nanoString expression. In addition, there were no outliers in the cluster analysis among the ameloblastoma cluster analysis indicating consistent results between fresh frozen and FFPE samples.

Strengths of the study included the use of LCM and universal RNA as a means of normalizing between arrays. Ameloblastoma presents with neoplastic epithelial tissue surrounded by stromal tissue making isolation very difficult. As a result, most investigations of ameloblastoma used samples that contain diverse cell populations such as the surrounding stroma which can obscure driver pathways from the actual neoplastic epithelial cells. The use of the universal RNA facilitated the use of the dentome as a comparison and also allows the use of the microarray data by other investigators using universal RNA for normalization.

In conclusion, our study isolated ameloblastoma epithelial and normal odontogenic cells using LCM to identify gene expression profiles and molecular pathways that are potentially important in the tumorigenesis of ameloblastoma. Ameloblastoma showed 2 distinct molecular profiles that were associated with different histological subtypes suggesting they could be receptive to different chemotherapeutic protocols. These results provide a wealth of information that can be used in future experimental and mechanistic studies, involving animal models and new pharmacogenomic approaches.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Hu, S. et al. Ameloblastoma Phenotypes Reflected in Distinct Transcriptome Profiles. Sci. Rep. 6, 30867; doi: 10.1038/srep30867 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Cynthia Suggs, MS for her work on the laser capture microdissection and microarrays and Gary Rosson, PhD from the UNC GPath Core for his work on the NanoString experiments. This study is supported by NIDCR Grant # DE016079.

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.T.W. designed the study, data collection was performed by J.T.W., R.P. and V.M. analysis was conducted by J.P. and S.H., interpretation and figure preparation was by S.H., K.D. and S.H. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors were involved in writing the paper and had final approval of the submitted version.

References

- Juuri E., Isaksson S., Jussila M., Heikinheimo K. & Thesleff I. Expression of the stem cell marker, SOX2, in ameloblastoma and dental epithelium. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 121, 509–516, doi: 10.1111/eos.12095 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehdev M. K., Huvos A. G., Strong E. W., Gerold F. P. & Willis G. W. Proceedings: Ameloblastoma of maxilla and mandible. Cancer 33, 324–333 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siriwardena B. S., Tennakoon T. M. & Tilakaratne W. M. Relative frequency of odontogenic tumors in Sri Lanka: Analysis of 1677 cases. Pathol. Res. Pract. 208, 225–230, doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2012.02.008 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avelar R. L. et al. Worldwide incidence of odontogenic tumors. J. Craniofac. Surg. 22, 2118–2123, doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182323cc7 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzawa N. et al. Primary ameloblastic carcinoma of the maxilla: A case report and literature review. Oncol. Lett. 9, 459–467, doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2654 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo D. Y., Feng C. J. & Guo J. B. Pulmonary metastases from an Ameloblastoma: case report and review of the literature. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 40, e470–e474, doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2012.03.006 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichart P. A., Philipsen H. P. & Sonner S. Ameloblastoma: biological profile of 3677 cases. Eur. J. Cancer. B Oral Oncol. 31B, 86–99 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M. et al. Treatment algorithm for ameloblastoma. Case Rep Dent. 2014, 121032, doi: 10.1155/2014/121032 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendenhall W. M., Werning J. W., Fernandes R., Malyapa R. S. & Mendenhall N. P. Ameloblastoma. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, 645–648, doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181573e59 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva I. et al. Achieving adequate margins in ameloblastoma resection: the role for intra-operative specimen imaging. Clinical report and systematic review. PLoS One 7, e47897, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047897 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carinci F. et al. Genetic expression profiling of six odontogenic tumors. J. Dent. Res. 82, 551–557 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikinheimo K. et al. Early dental epithelial transcription factors distinguish ameloblastoma from keratocystic odontogenic tumor. J. Dent. Res. 94, 101–111, doi: 10.1177/0022034514556815 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikinheimo K. et al. Gene expression profiling of ameloblastoma and human tooth germ by means of a cDNA microarray. J. Dent. Res. 81, 525–530 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J. et al. Oligonucleotide microarray analysis of ameloblastoma compared with dentigerous cyst. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 35, 278–285, doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00393.x (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVilliers P., Suggs C., Simmons D., Murrah V. & Wright J. T. Microgenomics of ameloblastoma. J. Dent. Res. 90, 463–469, doi: 10.1177/0022034510391791 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes C. C., Diniz M. G. & Gomez R. S. Progress towards personalized medicine for ameloblastoma. J. Pathol. 232, 488–491 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoradovskaya N. et al. Universal Reference RNA as a standard for microarray experiments. BMC Genomics 5, 20, doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-20 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S., Parker J. & Wright J. T. Towards unraveling the human tooth transcriptome: the dentome. PLoS One 10, e0124801, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124801 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberzon A. et al. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics 27, 1739–1740, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr260 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoadley K. A. et al. Multiplatform analysis of 12 cancer types reveals molecular classification within and across tissues of origin. Cell 158, 929–944, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.049 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiss G. K. et al. Direct multiplexed measurement of gene expression with color-coded probe pairs. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 317–325, doi: 10.1038/nbt1385 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y. et al. Comprehensive analysis of gene expression in the junctional epithelium by laser microdissection and microarray analysis. J. Periodontal Res. 45, 618–625, doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2010.01276.x (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens L. M. & Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 420, 860–867, doi: 10.1038/nature01322 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanahashi J. et al. Mutational analysis of Wnt signaling molecules in ameloblastoma with aberrant nuclear expression of beta-catenin. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 37, 565–570, doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00645.x (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siar C. H. et al. Differential expression of canonical and non-canonical Wnt ligands in ameloblastoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 41, 332–339, doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01104.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivlin N., Brosh R., Oren M. & Rotter V. Mutations in the p53 Tumor Suppressor Gene: Important Milestones at the Various Steps of Tumorigenesis. Genes Cancer 2, 466–474, doi: 10.1177/1947601911408889 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C., Wilhelm D. & Koopman P. Sox genes and cancer. Cytogenet Genome Res 105, 442–447, doi: 10.1159/000078217 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N. A. et al. Activating FGFR2-RAS-BRAF mutations in ameloblastoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 5517–5526, doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1069 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney R. T. et al. Identification of recurrent SMO and BRAF mutations in ameloblastomas. Nat. Genet. 46, 722–725, doi: 10.1038/ng.2986 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurppa K. J. et al. High frequency of BRAF V600E mutations in ameloblastoma. J. Pathol. 232, 492–498, doi: 10.1002/path.4317 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell-Dorris E. R., O’Leary J. J. & Sheils O. M. BRAFV600E: implications for carcinogenesis and molecular therapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 10, 385–394, doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0799 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye F. J., Ivey A. M., Drane W. E., Mendenhall W. M. & Allan R. W. Clinical and radiographic response with combined BRAF-targeted therapy in stage 4 ameloblastoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 107, 378, doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju378 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikinheimo K., Kurppa K. J. & Elenius K. Novel targets for the treatment of ameloblastoma. J. Dent. Res. 94, 237–240, doi: 10.1177/0022034514560373 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravo M. et al. Quantitative expression profiling of highly degraded RNA from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded breast tumor biopsies by oligonucleotide microarrays. Lab. Invest. 88, 430–440, doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.11 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdueva D., Wing M., Schaub B., Triche T. & Davicioni E. Quantitative expression profiling in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples by affymetrix microarrays. J Mol Diagn. 12, 409–417, doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090155 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkov V. A. et al. Multiplexed measurements of gene signatures in different analytes using the Nanostring nCounter Assay System. BMC Res. Notes 2, 80, doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-80 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.