Abstract

Background and objectives

Current measures for predicting renal functional decline in patients with type 2 diabetes with preserved renal function are unsatisfactory, and multiple markers assessing various biologic axes may improve prediction. We examined the association of four biomarker-to-creatinine ratio levels (monocyte chemotactic protein-1, IL-18, kidney injury molecule-1, and YKL-40) with renal outcome.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We used a nested case-control design in the Action to Control Cardiovascular Disease Trial by matching 190 participants with ≥40% sustained eGFR decline over the 5-year follow-up period to 190 participants with ≤10% eGFR decline in a 1:1 fashion on key characteristics (age within 5 years, sex, race, baseline albumin-to-creatinine ratio within 20 μg/mg, and baseline eGFR within 10 ml/min per 1.73 m2), with ≤10% decline. We used a Mesoscale Multiplex Platform and measured biomarkers in baseline and 24-month specimens, and we examined biomarker associations with outcome using conditional logistic regression.

Results

Baseline and 24-month levels of monocyte chemotactic protein-1-to-creatinine ratio levels were higher for cases versus controls. The highest quartile of baseline monocyte chemotactic protein-1-to-creatinine ratio had fivefold greater odds, and each log increment had 2.27-fold higher odds for outcome (odds ratio, 5.27; 95% confidence interval, 2.19 to 12.71 and odds ratio, 2.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.44 to 3.58, respectively). IL-18-to-creatinine ratio, kidney injury molecule-1-to-creatinine ratio, and YKL-40-to-creatinine ratio were not consistently associated with outcome. C statistic for traditional predictors of eGFR decline was 0.70, which improved significantly to 0.74 with monocyte chemotactic protein-1-to-creatinine ratio.

Conclusions

Urinary monocyte chemotactic protein-1-to-creatinine ratio concentrations were strongly associated with sustained renal decline in patients with type 2 diabetes with preserved renal function.

Keywords: albuminuria; renal injury; renal fibrosis; chronic kidney disease; Biomarkers; Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2; Follow-Up Studies; Inflammation; CCL2 protein, human; CHI3L1 protein, human

Introduction

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) develops in >40% of patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and affects >7 million people in the United States (1). The prevalence of DKD has increased by >50% over the past few decades, it is now the single largest cause of ESRD, and it accounts for 44% of patients with incident ESRD (2). DKD is a major risk factor for other complications, including coronary artery disease, stroke, and retinopathy (3). Thus, DKD is a public health problem and places a significant burden on the health care system.

Current markers for prognostication of DKD include eGFR and albuminuria. However, in patients with T2D and preserved renal function, eGFR and albuminuria are only modestly useful for risk prediction (4). In addition, albuminuria has significant limitations, including regression spontaneously or after therapy. Recent epidemiologic studies have also shown DKD progression in the absence of albuminuria (5,6). Thus, newer markers for DKD prognostication are urgently needed to implement preventive efforts early and shed light on therapeutic targets.

Although the Action to Control Cardiovascular Disease (ACCORD) Trial was a cardiovascular (CV) outcome trial, the effect of intensive risk factor control on microvascular outcomes, including nephropathy, has been well studied (7). Patients selected were at risk for CV events but had preserved renal function at baseline. However, they were also at risk for renal decline because of a long history of poor glycemic and BP control.

Because DKD is a complex, multifactorial disease, multiple markers representing distinct biologic pathways have better predictive value than a single marker. The interlinked axes of inflammation, injury, and fibrosis are key in DKD progression. We chose to study a biomarker panel representing various pathways of DKD as well as biomarkers, which have reliable assays and can be readily multiplexed. We chose to study two inflammatory biomarkers: monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and IL-18. MCP-1 has been associated with DKD progression in two small studies (8,9), and IL-18 is associated with eGFR decline in nondiabetic populations (10). We also studied kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), which has been associated with incident and progressive CKD in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Study cohort (11), and a repair/fibrosis marker, YKL-40, which is upregulated in AKI and elevated in CKD and DKD (12,13). We sought to examine the association between these biomarkers with sustained eGFR decline in a multiethnic T2D cohort with preserved renal function and compare them with traditional predictors.

Materials and Methods

The ACCORD Trial

The ACCORD Trial enrolled individuals with T2D and a hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) of ≥7.5% between the ages of 40 and 79 years old with CV disease or between the ages of 55 and 79 years old with anatomic evidence of significant atherosclerosis, albuminuria, left ventricular hypertrophy, or at least two additional risk factors for CV disease at 77 clinical centers across the United States and Canada (7). All 10,251 patients were randomly assigned to receive intensive therapy targeting an HbA1C of <6.0% or standard therapy targeting a level of 7.0%–7.9%. With a double two by two factorial design, 4733 patients were randomly assigned to lower their BP by receiving either intensive therapy (systolic BP target <120 mmHg) or standard therapy (systolic BP target <140 mmHg). Similarly, 5518 patients treated with open label simvastatin were randomly assigned to receive fenofibrate or placebo. Total follow-up of patients was 5 years, with banked urine specimens from the baseline visit and 24 months.

Selection of Cases and Controls

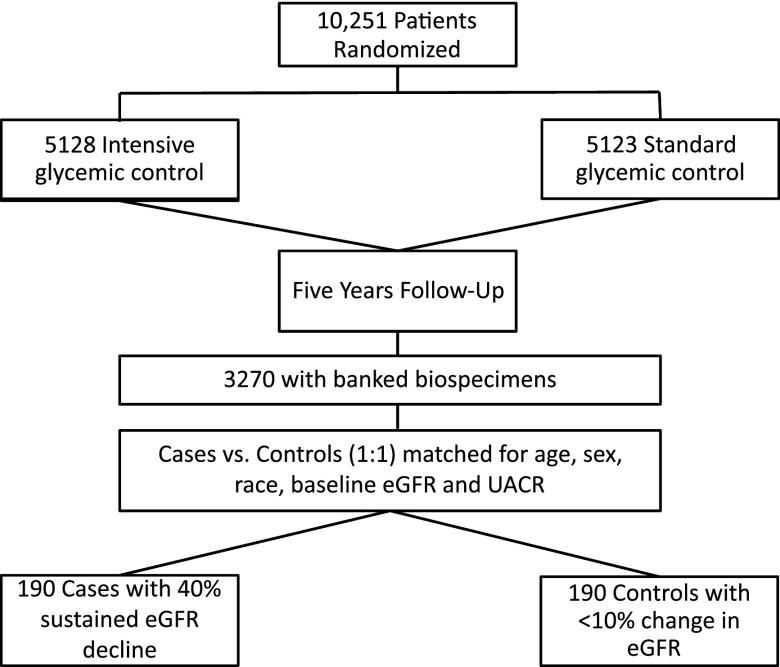

Our primary outcome was a sustained (on two or more visits 3 months apart) decline in eGFR of ≥40% from baseline during the 5-year follow-up. This is independently associated with mortality and ESRD (14). We also considered a secondary outcome of CKD stage 3b or higher defined as an eGFR≤45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 on two or more values during the 5-year follow-up for sensitivity analyses. We used a nested case-control approach to select cases and controls. Of 10,251 ACCORD Trial participants, 3270 had both plasma and urine available at baseline and 24 months. There were no significant differences between the participants with banked biospecimens and those from the overall cohort (Supplemental Table 1). Among participants with available biospecimens, we selected cases with outcome and individually matched them to controls with ≤10% eGFR decline in a 1:1 fashion on key characteristics (age within 5 years, sex, race, baseline albumin-to-creatinine ratio within 20 μg/mg, and baseline eGFR within 10 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Total sample size was 190 cases and 190 controls (Figure 1). Because of the deidentified nature of the study, it was deemed Institutional Review Board exempt.

Figure 1.

Selection of cases and controls from overall cohort. This figure shows the selection of the nested cases and controls from the overall cohort. UACR, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

Exposure Ascertainment

Our primary and secondary exposures of interest were the baseline and 24-month urine biomarker concentrations, respectively. They were indexed to corresponding urine creatinine to adjust for variability in urine concentration and osmolality (15).

Assessment of Covariates

Body mass index was defined as weight divided by the square of height (kilograms per meter2). BP was on the basis of the average of three measurements using an automated device (Omron 907) after 5 minutes of rest with the participant seated in a chair. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was calculated with a standardized formula. HbA1C was measured by HPLC. Serum creatinine was determined using the Roche Creatinine Plus Enzymatic Assay with spectrometric analysis on a Roche Double Modular P Analytics Analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). The results are traceable to the isotope dilution mass spectrometry reference method (16). eGFR was calculated from the measured serum creatinine by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation (17,18). Urine albumin was determined by immunonephelometry on a Siemens BN II Nephelometer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY), and urinary creatinine was determined by a modified Jaffé reaction (16). Urinary albumin excretion was estimated from a single spot urine collection by computing the albumin-to-creatinine ratio in units of milligrams per gram. All laboratory and vital measurements were conducted as part of the ACCORD Trial parent study. Medication use, CV disease, and smoking history were all self-reported by participants.

Biospecimens Storage and Analytes Measurement

The urine samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. Urine biomarkers were measured using the four–plex prototype assay on the Mesoscale Platform (Meso Scale Diagnostics, Gaithersburg, MD), which uses proprietary electrochemiluminescence detection methods combined with patterned arrays. The four–plex multiplex assays were validated earlier using urine samples from two different cohorts with respect to its sensitivity, linearity, and recovery. All of the samples were measured using the same lot of reagents and plates. The intra–assay coefficient of variation for the calibrators was <10%, and the interassay coefficients of variation for the calibrators were 2.2%–6.8% for urinary IL-18 (uIL-18), 5.02%–9.29% for urinary kidney injury molecule-1 (uKIM-1), 3.6%–15.25% for urinary monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (uMCP-1), and 1.63%–12.13% for urinary YKL-40 (uYKL-40). The average lower limit of detection obtained from multiple runs was 0.09 pg/ml for uIL-18, 0.28 pg/ml for uKIM-1, 0.05 pg/ml for uMCP-1, and 0.16 pg/ml for uYKL-40. Pooled urine samples from participants undergoing cardiac surgery (quality control) from the Translational Research Investigating Biomarker Endpoints-AKI Study cohort were run in duplicate along with samples on each plate to account for any plate to plate variability. The interassay coefficients of variation for the quality control sample were 11.12% for uIL-18, 13.53% for uKIM-1, 9.68% for uMCP-1, and 8.57% for uYKL-40.

Statistical Analyses

We expressed descriptive results for the participants’ baseline characteristics and biomarkers via means and SDs or for skewed variables, medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). We made statistical comparisons between groups by paired t tests for data that were normally distributed, Wilcoxon tests for skewed continuous data, and McNemar test for categorical data. Because the distribution of concentrations of urinary biomarker-to-creatinine ratios was rightward skewed, we used each marker as a natural log–transformed continuous variable. We also categorized each marker into quartiles on the basis of the biomarker distributions. Using multivariable conditional logistic regression, we evaluated the associations of biomarker-to-creatinine ratio with renal decline. We present results for the biomarkers both as per natural log increment and for each of the top three quartiles compared with the bottom quartile.

We also adjusted for unmatched risk factors (former/current smoker, HbA1C, CV disease history, intensive glycemic control, intensive BP control, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I)/angiotensin-2 receptor blockers (ARBs) use, fibrate use, and thiazolidinedione use) in a series of staged models. Also, to account for imperfect matching, we additionally adjusted for baseline urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) and CKD-EPI eGFR. Because baseline albuminuria is a strong predictor of renal decline, we also stratified by moderate albuminuria (<30 versus ≥30 mg/g) to assess for change in association. We did not stratify for baseline eGFR, because all cases and controls had preserved eGFR at baseline. We assessed discrimination and improvement in discrimination through the C statistic, which was bootstrapped with 1000 iterations with resampling to adjust for optimism bias. We also used Akaike information criterion and Schwartz Bayesian information criterion to compare the fit of various models, The initial model consisted of the traditional predictors of renal function decline (baseline eGFR, UACR, age, sex, race, CV disease history, MAP, baseline HbA1C, ACEI/ARB, and fibrates) selected on the basis of prior studies of DKD progression (19). We added biomarkers individually and then, in pairwise combinations initially in all participants and stratified by baseline albuminuria. To account for multiple testing, we established a heuristic significance threshold at P<0.03 for association analysis; the Bonferroni correction was considered to be punitive, because the biomarkers were correlated with each other. We conducted all analyses using STATA SE, version 12 (StataCorp., College Station, TX).

Results

Characteristics of Cases and Controls at Baseline and Follow-Up

The 380 participants (190 matched case-control pairs) were well matched with regards to age, sex, race, baseline CKD-EPI eGFR, and UACR (Table 1). Cases and controls had similar body mass index, diabetes duration, and HbA1C. In contrast, cases had more CV disease and higher baseline MAP, and a greater proportion was randomized to fibrates. Cases had lower eGFR than controls at the end of follow-up (46 versus 83 ml/min per 1.73 m2; P<0.01), but there was no significant difference in UACR.

Table 1.

Clinical and renal marker characteristics by case-control status

| Clinical and Renal Marker Characteristics | Controls, n=190 | Cases, n=190 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics of participants | |||

| Age, yra | 61.9 (5.4) | 62.3 (5.6) | 0.48 |

| Womena | 93 (48.9) | 92 (48.4) | 0.80 |

| Racea | 0.78 | ||

| White | 141 (74.2) | 141(74.2) | |

| Black | 20 (10.5) | 20 (10.5) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 16 (8.4) | 16 (8.4) | |

| Other | 13 (6.8) | 13 (6.8) | |

| Baseline mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 95 (10.3) | 97.1 (11.4) | 0.06 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 32.6 (5.5) | 33.4 (5.9) | 0.18 |

| History of cardiovascular disease | 44 (23.5) | 76 (40) | 0.002 |

| Former/current smoker | 98 (52.4) | 115 (60.5) | 0.11 |

| Duration of diabetes, yr | 10.8 (7.8) | 11.9 (7.9) | 0.18 |

| Baseline hemoglobin A1C, % | 8.4 (1.1) | 8.4 (1.01) | 0.65 |

| Use of ACEI or ARB at baseline | 122 (65.2) | 140 (73.4) | 0.09 |

| Use of thiazolidinediones at baseline | 33 (17.7) | 36 (19) | 0.65 |

| Use of sulfonylureas at baseline | 80 (42.8) | 90 (47.4) | 0.37 |

| Use of insulin at baseline | 69 (37) | 78 (41) | 0.40 |

| Use of biguanides at baseline | 116 (62) | 135 (71) | 0.10 |

| Randomized to fibrate arm | 28 (15) | 84 (44.2) | 0.003 |

| Randomized to intensive glycemic control | 95 (50.8) | 101 (53.2) | 0.72 |

| Randomized to intensive BP control | 42 (22.5) | 49 (25.8) | 0.35 |

| Traditional renal markers | |||

| Baseline CKD-EPI eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2a | 90.2 [78.6–95.9] | 87 [77.2–93.7] | 0.31 |

| CKD-EPI eGFR at end of follow-up, ml/min per 1.73 m2b | 83.1 [65.3–92.0] | 46.3 [37.4–55.9] | <0.001 |

| Urine albumin-to-Cr ratio, mg/mga | 20.5 [7.6–66.4] | 20 [7.8–104] | 0.10 |

| Urine albumin-to-Cr ratio at end of follow-up, mg/mgb | 19.3 [7.3–64.9] | 18.7 [6.9–138.4] | 0.96 |

| Baseline urinary Cr, mg/dl | 112.4 [64.7–162.8] | 114.1 [80.2–142.8] | 0.80 |

| Novel renal markers | |||

| Urinary MCP-1-to-Cr ratio at baseline | 1.29 [0.90–2.05] | 1.76 (1.19–2.82) | <0.001 |

| Urinary MCP-1-to-Cr ratio at 24 mo | 1.31 [0.88–1.85] | 1.53 [0.93–2.30] | 0.01 |

| Urinary IL-18-to-Cr ratio at baseline | 0.28 (0.15–0.46) | 0.28 (0.16–0.57) | 0.25 |

| Urinary IL-18-to-Cr ratio at 24 mo | 0.28 [0.15–0.47] | 0.27 [0.14–0.44] | 0.36 |

| Urinary KIM-1-to-Cr ratio at baseline | 8.46 (4.73–12.2) | 9.15 (5.48–13.5) | 0.38 |

| Urinary KIM-1-to-Cr ratio at 24 mo | 6.76 [3.72–10.51] | 6.28 [4.04–10.46] | 0.48 |

| Urinary YKL-40-to-Cr ratio at baseline | 2.37 (0.71–5.03) | 3.01 (1.00–5.77) | 0.32 |

| Urinary YKL-40-to-Cr ratio at 24 mo | 3.27 [1.30–6.67] | 2.74 [0.76–9.11] | 0.44 |

Values are presented as means (SDs) or medians [interquartile ranges] for continuous values and N (%) for categorical values. ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotension-II receptor blockers; CKD-EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration; Cr, creatinine; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule-1.

Indicates variables matched in case-control study.

Missing in 28 of 380 (7.3%).

Cases had higher baseline median MCP-1-to-creatinine ratio compared with controls (1.76; [IQR, 1.19–2.82 pg/mg versus 1.29; IQR, 0.90–2.05 pg/mg; P<0.01); baseline levels of other markers did not differ. Similarly, median MCP-1-to-creatinine ratio levels at 24 months were higher in cases versus controls (1.53; IQR, 0.93–2.30 pg/mg versus 1.31; IQR, 0.88–1.85 pg/mg; P<0.01), and 24-month levels of other biomarker-to-creatinine ratio levels were not different. Although the mortality did not differ between cases and controls, cases had a higher proportion of nonfatal CV events (15.3% versus 7.4%; P=0.02).

Association of Biomarker-to-Creatinine Ratio with Baseline Characteristics

Baseline MCP-1-to-creatinine ratio and KIM-1-to-creatinine ratio correlated with UACR. Baseline IL-18-to-creatinine ratio and YKL-40-to-creatinine ratio had weak associations with higher baseline eGFR. All markers weakly correlated with each other (Table 2).

Table 2.

Partial Pearson correlations of natural log–transformed urinary biomarkers indexed to urinary creatinine with each other and participant characteristics

| Biomarker | Age, yr | MAP, mmHg | Baseline eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | UACR, mg/mg | HbA1C, % | BMI, kg/m2 | MCP-1-to-Cr, pg/mg | KIM-1-to-Cr, pg/mg | IL-18-to-Cr, pg/mg | YKL-40-to-Cr, pg/mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCP-1-to-Cr, pg/mg | −0.001 | 0.14a | 0.05 | 0.26a | 0.11b | 0.06 | 0.50b | 0.25b | 0.20b | |

| KIM-1-to-Cr, pg/mg | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.004 | 0.21b | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.50b | 0.24b | 0.16b | |

| IL-18-to-Cr, pg/mg | −0.05 | 0.11b | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.23a | 0.16a | 0.25b | 0.24b | 0.29b | |

| YKL-40-to-Cr, pg/mg | −0.02 | 0.13b | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.14a | 0.02 | 0.20b | 0.16b | 0.29b |

MAP, mean arterial pressure; UACR, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio; HbA1C, hemoglobin A1C; BMI, body mass index; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; Cr, creatinine; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule-1.

P<0.01.

P<0.05.

Association of Biomarker-to-Creatinine Ratio with Sustained eGFR Decline

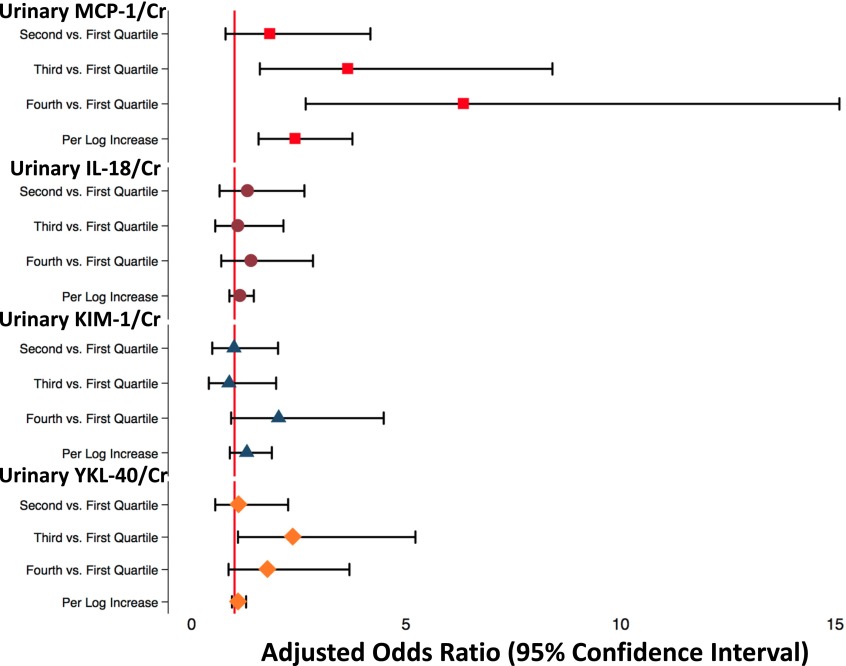

There was a graded relationship between quartiles of uMCP-1-to-creatinine ratio at baseline and eGFR decline (Figure 2, Table 3). The top quartile of MCP-1-to-creatinine ratio was associated with fivefold odds of sustained eGFR decline (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 5.27; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 22.19 to 12.71; P<0.01), and each log increment in MCP-1-to-creatinine ratio was associated with twofold higher odds of outcome (aOR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.44 to 3.58; P<0.01), even after additionally adjusting for baseline eGFR and UACR. In addition, MCP-1-to-creatinine ratio was associated with sustained eGFR decline, regardless of baseline albuminuria (top quartile versus bottom quartile: aOR, 6.58; 95% CI, 1.91 to 17.22 in participants without albuminuria and aOR, 5.13; 95% CI, 1.78 to 13.30 in participants with albuminuria) (Supplemental Table 2). There were no significant associations with eGFR decline with regards to IL-18-to-creatinine ratio, KIM-1-to-creatinine ratio, or YKL-40-to-creatinine ratio continuously. However, the second quartile of YKL-40-to-creatinine ratio was associated with a 2.37 times higher odds of eGFR decline, suggesting a U-shaped relationship. In addition, we also analyzed the association of urinary biomarkers not indexed to urinary creatinine with sustained eGFR decline and found similar results (Supplemental Table 3).

Figure 2.

Adjusted odds ratios for urinary biomarker-to-creatinine (Cr) ratio levels by quartile and continuously. Forest plots shows the odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. The vertical red line indicates an odds ratio of one. Odds ratios for urinary monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) -to-Cr ratio (red squares), urinary IL-18-to-Cr ratio (maroon circles), urinary kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) -to-Cr ratio (blue triangles), and urinary YKL-40-to-Cr ratio (orange diamonds) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals are shown.

Table 3.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for sustained 40% decline in eGFR for urinary biomarkers-to-creatinine ratio modeled categorically and continuously

| Concentration of Urine Biomarkers | Model 1 OR (95% CI) | Model 2 OR (95% CI) | Model 3 OR (95% CI) | Model 4 OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary MCP-1-to-Cr, pg/mg | ||||

| ≤0.88 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 0.89–1.35 | 1.49 (0.75 to 2.96) | 1.66 (0.80 to 3.45) | 1.96 (0.83 to 4.65) | 1.97 (0.82 to 4.73) |

| 1.36—2.11 | 2.51 (1.27 to 4.97) | 2.82 (1.37 to 5.82) | 3.40 (1.45 to 7.98) | 3.72 (1.55 to 8.93) |

| >2.11 | 3.95 (1.98 to 7.84) | 4.35 (2.08 to 9.08) | 6.57 (2.70 to 16.01) | 5.27(2.19 to 12.71) |

| OR per 1-U increment in log MCP-1/mg | 1.92 (1.37 to 2.69) | 1.98 (1.38 to 2.84) | 2.46 (1.57 to 3.87) | 2.27 (1.44 to 3.58) |

| Urinary IL-18-to-Cr, pg/mg | ||||

| ≤0.14 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 0.15–0.25 | 1.26 (0.69 to 2.31) | 1.28 (0.68 to 2.43) | 1.18 (0.57 to 2.44) | 1.33 (0.62 to 2.84) |

| 0.26–0.44 | 0.94 (0.52 to 1.67) | 0.90 (0.49 to 1.66) | 0.96 (0.48 to 1.92) | 1.05 (0.51 to 2.17) |

| ≥0.45 | 1.39 (0.78 to 2.51) | 1.30 (0.68 to 2.43) | 1.35 (0.66 to 2.78) | 1.43 (0.67 to 3.06) |

| OR per 1-U increment in log IL-18/mg | 1.12 (0.91 to 1.38) | 1.08 (0.86 to 1.35) | 1.11 (0.86 to 1.44) | 1.13 (0.87 to 1.49) |

| Urinary KIM-1-to-Cr, pg/mg | ||||

| ≤4.28 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 4.29–7.35 | 1.14 (0.62 to 2.09) | 1.24 (0.64 to 2.39) | 1.24 (0.64 to 2.39) | 1.20 (0.55 to 2.63) |

| 7.36–11.89 | 0.83 (0.44 to 1.59) | 0.83 (0.42 to 1.67) | 0.83 (0.42 to 1.67) | 0.93 (0.40 to 2.15) |

| ≥11.90 | 1.47 (0.78 to 2.78) | 1.57 (0.80 to 0.308) | 1.57 (0.80 to 3.08) | 1.76 (0.76 to 4.09) |

| OR per 1-U increment in log KIM-1/mg | 1.07 (0.79 to 1.43) | 1.09 (0.79 to 1.49) | 1.29 (0.89 to 1.87) | 1.21 (0.81 to 1.80) |

| Urinary YKL-40-to-Cr, pg/mg | ||||

| ≤0.94 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 2.82–5.85 | 0.88 (0.49 to 1.59) | 0.85 (0.45 to 1.59) | 1.07 (0.51 to 2.25) | 1.14 (0.53 to 2.46) |

| 2.82–5.85 | 1.89 (1.00 to 3.51) | 1.92 (1.00 to 3.73) | 2.55 (1.13 to 5.77) | 2.96 (1.26 to 6.93) |

| ≥5.86 | 1.30 (0.73 to 2.33) | 1.35 (0.72 to 2.53) | 1.73 (0.81 to 3.66) | 1.91 (0.86 to 4.23) |

| OR per 1-U increment in log YKL-40/mg | 1.04 (0.92 to 1.17) | 1.17 (0.70 to 1.95) | 1.08 (0.92 to 1.27) | 1.09 (0.93 to 1.29) |

Model 1: conditional logistic model with cases and controls. Model 2: model 1 and diabetic/cardiovascular risk factors (hemoglobin A1C, mean arterial pressure, history of cardiovascular disease, and intensive glycemic and BP control). Model 3: model 2 and medications (fibrates, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors [ACEIs], angiotensin receptor blockers, and thiazolidinedione). Model 4: model 3, baseline eGFR, and urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio. OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; Cr, creatinine; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule-1.

In a sensitivity analysis with the outcome of CKD stage 3b or higher with 171 matched cases and controls, uMCP-1-to-creatinine ratio was associated with incident CKD stage 3b both continuously and categorically. The other biomarkers were not associated with CKD stage 3b (Supplemental Table 4). There was also no association with change in urinary biomarker level from baseline to 24 months and sustained eGFR decline (Supplemental Table 5). When the associations of 24-month concentrations of biomarker levels were analyzed with outcome, MCP-1 was associated with eGFR decline (odds ratio, 1.38; 95% confidence interval 1.04 to 1.84, for each log increment in log MCP-1-to-creatinine ratio). However, this was attenuated by adjusting for change in eGFR and UACR over 24 months. None of the other urinary biomarkers were consistently associated with outcome (Supplemental Table 6).

Novel Biomarkers Compared with Traditional Predictors of Renal Decline

Adding MCP-1-to-creatinine ratio to a model consisting of traditional predictors significantly improved the model fit. In addition, the C statistic improved with addition of uMCP-1-to-creatinine ratio from 0.70 to 0.74 (P=0.02). IL-18-to-creatinine ratio, KIM-1-to-creatinine ratio, and YKL-40-to-creatinine ratio did not improve either model fit or C statistic (Table 4). After stratifying by albuminuria, none of the biomarkers, individually or in combination, improved the C statistic, possibly because of a loss of power (Table 5).

Table 4.

C statistic and measures of model fit for the conventional predictors with individual or combined biomarker-to-creatinine ratio levels

| Conventional Predictors with Individual/Combined Biomarker Levels | AIC | BIC | C Statistic (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPa | 485.7 | 528.8 | 0.70 (0.65 to 0.76) | Reference |

| TP + uMCP-1-to-Cr | 470.7 | 517.7 | 0.74 (0.69 to 0.79) | 0.02 |

| TP + uIL-18-1-to-Cr | 486 | 533.1 | 0.71 (0.66 to 0.76) | 0.99 |

| TP + uKIM-1-to-Cr | 486.6 | 533.7 | 0.71 (0.66 to 0.76) | 0.97 |

| TP + uYKL-40-to-Cr | 486.2 | 533.2 | 0.71 (0.66 to 0.76) | 0.96 |

| TP + uMCP-1-to-Cr + uIL-18-1-to-Cr | 475.8 | 526.8 | 0.74 (0.69 to 0.79) | 0.02 |

| TP + uMCP-1-to-Cr + uKIM-1-to-Cr | 471.6 | 522.6 | 0.74 (0.69 to 0.79) | 0.02 |

| TP + uMCP-1-to-Cr + uYKL-40-to-Cr | 475.8 | 526.8 | 0.74 (0.69 to 0.79) | 0.02 |

| TP + uIL-18-to-Cr + uKIM-1-to-Cr | 490.8 | 541.8 | 0.71 (0.66 to 0.76) | 0.96 |

| TP + uIL-18-to-Cr + uYKl-40-to-Cr | 490.8 | 541.9 | 0.70 (0.65 to 0.76) | 0.92 |

| TP + uKIM-1-to-Cr + uYKl-40-to-Cr | 490.9 | 541.9 | 0.71 (0.66 to 0.76) | 0.96 |

| TP + uMCP-1-to-Cr + uIL-18-1-to-Cr + uKIM-1-to-Cr | 473.6 | 528.5 | 0.74 (0.69 to 0.79) | 0.02 |

| TP + uIL-18-1-to-Cr + uKIM-1-to-Cr + uYKL-40-to-Cr | 492.7 | 547.6 | 0.71 (0.66 to 0.76) | 0.96 |

| TP + all biomarker-to-Cr | 472.3 | 531.1 | 0.74 (0.69 to 0.79) | 0.03 |

AIC, Akaike information criterion; BIC, Schwartz Bayesian information criterion; TP, traditional predictors; uMCP-1, urinary monocyte chemotactic protein-1; Cr, creatinine; uIL-18, urinary IL-18; uKIM-1, urinary kidney injury molecule-1; uYKL-40, urine YKL-40.

Sex, body mass index, age, hemoglobin A1C, eGFR (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration), fibrate intervention, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I)/angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) use, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio, and cardiovascular disease history.

Table 5.

C statistic and measures of model fit for the conventional predictors with individual or combined biomarker-to-creatinine ratio levels stratified by baseline albuminuria

| Albuminuria Stratum | AIC | BIC | AUC (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants without albuminuria, n=214 | ||||

| TPa | 279.1 | 316.1 | 0.74 (0.68 to 0.81) | Reference |

| TP + uMCP-1-to-Cr | 267.3 | 307.6 | 0.78 (0.71 to 0.84) | 0.13 |

| TP + uIL-18-1-to-Cr | 279 | 319.3 | 0.75 (0.68 to 0.81) | 0.95 |

| TP + uKIM-1-to-Cr | 276.1 | 317.0 | 0.75 (0.69 to 0.82) | 0.70 |

| TP + uYKL-40-to-Cr | 268.7 | 312.4 | 0.78 (0.72 to 0.84) | 0.11 |

| TP + uMCP-1-to-Cr + uIL-18-1-to-Cr | 268.5 | 312.2 | 0.78 (0.71 to 0.84) | 0.15 |

| TP + uMCP-1-to-Cr + uKIM-1-to-Cr | 268.5 | 312.1 | 0.77 (0.71 to 0.84) | 0.12 |

| TP + uMCP-1-to-Cr + uYKL-40-to-Cr | 279 | 322.7 | 0.75 (0.69 to 0.82) | 0.44 |

| TP + uIL-18-to-Cr + uKIM-1-to-Cr | 278.4 | 322 | 0.75 (0.69 to 0.82) | 0.67 |

| TP + uIL-18-to-Cr + uYKl-40-to-Cr | 278.7 | 322.3 | 0.75 (0.69 to 0.82) | 0.63 |

| TP + uKIM-1-to-Cr + uYKl-40-to-Cr | 269.7 | 316.7 | 0.78 (0.72 to 0.84) | 0.11 |

| TP + uMCP-1-to-Cr + uIL-18-1-to-Cr + uKIM-1-to-Cr | 280.3 | 327.3 | 0.75 (0.69 to 0.82) | 0.64 |

| TP + uIL-18-1-to-Cr + uKIM-1-to-Cr + uYKL-40-to-Cr | 279.7 | 326.6 | 0.75 (0.69 to 0.82) | 0.94 |

| TP + all biomarker-to-Cr | 271.3 | 321.7 | 0.78 (0.72 to 0.84) | 0.12 |

| Participants with albuminuria, n=166 | ||||

| TPa | 211.9 | 245.9 | 0.75 (0.68 to 0.83) | Reference |

| TP + uMCP-1-to-Cr | 212.2 | 249.3 | 0.76 (0.69 to 0.83) | 0.48 |

| TP + uIL-18-1-to-Cr | 213.8 | 250.9 | 0.75 (0.68 to 0.82) | 0.96 |

| TP + uKIM-1-to-Cr | 213.2 | 250.2 | 0.76 (0.69 to 0.83) | 0.34 |

| TP + uYKL-40-to-Cr | 213.7 | 250.8 | 0.75 (0.68 to 0.83) | 0.88 |

| TP + uMCP-1-to-Cr + uIL-18-1-to-Cr | 213.9 | 254 | 0.76 (0.69 to 0.84) | 0.28 |

| TP + uMCP-1-to-Cr + uKIM-1-to-Cr | 211.7 | 251.8 | 0.76 (0.69 to 0.84) | 0.35 |

| TP + uMCP-1-to-Cr + uYKL-40-to-Cr | 213.6 | 253.7 | 0.76 (0.69 to 0.83) | 0.34 |

| TP + uIL-18-to-Cr + uKIM-1-to-Cr | 211.7 | 251.8 | 0.76 (0.69 to 0.84) | 0.35 |

| TP + uIL-18-to-Cr + uYKl-40-to-Cr | 215.7 | 255.8 | 0.75 (0.68 to 0.83) | 0.86 |

| TP + uKIM-1-to-Cr + uYKl-40-to-Cr | 215.0 | 255.2 | 0.76 (0.68 to 0.83) | 0.43 |

| TP + uMCP-1-to-Cr + uIL-18-1-to-Cr + uKIM-1-to-Cr | 212.9 | 256.1 | 0.77 (0.69 to 0.84) | 0.26 |

| TP + uIL-18-1-to-Cr + uKIM-1-to-Cr + uYKL-40-to-Cr | 217 | 260.2 | 0.76 (0.68 to 0.83) | 0.38 |

| TP + all biomarker-to-Cr | 214.8 | 261.1 | 0.77 (0.70 to 0.84) | 0.23 |

Albuminuria defined by urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g. AIC, Akaike information criterion; BIC, Schwartz Bayesian information criterion; AUC, area under the curve; TP, traditional predictors; uMCP-1, urinary monocyte chemotactic protein-1; Cr, creatinine; uIL-18, urinary IL-18; uKIM-1, urinary kidney injury molecule-1; uYKL-40, urine YKL40.

Sex, body mass index, age, hemoglobin A1C, eGFR (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration), fibrate intervention, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I)/angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) use, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio, and cardiovascular disease history.

Discussion

This analysis evaluated the performance of four urinary biomarkers, representative of renal inflammation, injury, and fibrosis, with renal outcome in a nested case-control study from a large ambulatory cohort with T2D and preserved eGFR. Although several studies have examined uKIM-1 and uIL-18 as biomarkers for renal outcomes with mixed results, there are few studies on MCP-1 and YKL-40. We observed that MCP-1-to-creatinine ratio was independently associated with sustained eGFR decline in the setting of glycemic and BP control and independent of albuminuria. However, the three other urinary markers were not associated with the renal outcome.

Ongoing inflammation, injury, and tubulointerstitial fibrosis are universal in all progressive CKD, including DKD (20,21). A multidimensional panel assessing these interlinked axes could characterize additional kidney health dimensions and accurately subphenotype patients at high risk. Thus, we assessed a multimarker panel of four urinary biomarkers representing axes of CKD progression. Moreover, because of similar dilutions and compatibility, we were able to assay these four urinary markers as a multiplex assay using only a total of 10 μL urine, which improves detection limits, reduces variation, improves time and efficacy, and substantially reduces cost. Additionally, we also measured these markers at baseline and 24 months, thus assessing association of change over time.

MCP-1 is a member of the chemokine family that promotes recruitment and transformation of monocytes into macrophages (22). Kidney cells secrete MCP-1 in response to an inflammatory stimuli, and MCP-1 is known to be upregulated in kidney diseases as part of ongoing inflammation (23). In murine models, high glucose levels stimulate MCP-1 mRNA synthesis and consequent uMCP-1 expression by a pathway involving activation of protein kinase C, oxidative stress via peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor–γ, and nuclear translocation of the transcription factor NF-κB (24–26). In addition, blocking MCP-1 receptor suppresses inflammation and ameliorates glomerulosclerosis in DKD rodent models (27). Human studies assessing uMCP-1 have been limited by small sample size and/or lack of clinically relevant outcomes (9,10,27,28). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that assessed the association of uMCP-1 with meaningful renal outcomes in a large sample of patients with T2D after adjusting for additional covariates, including thiazolidinediones, which have been associated with lower plasma MCP-1 levels (29). Baseline uMCP-1-to-creatinine ratio provided robust risk stratification, although uMCP-1-to-creatinine ratio concentrations did not increase over 2 years in those who developed the renal outcome, and associations of 24-month uMCP-1-to-creatinine ratio levels with outcome were attenuated after adjusting for eGFR/UACR change over 24 months. Although our results with uMCP-1-to-creatinine ratio and renal decline are encouraging, they need to be further validated. Thus, uMCP-1-to-creatinine ratio could be a valuable tool that risk stratifies participants for renal decline, especially those with normal eGFR and mild to moderate albuminuria.

uIL-18 is a proinflammatory cytokine of the IL-1 superfamily, and it is known to be upregulated in response to ischemia-reperfusion injury (30). Although uIL-18 has been extensively studied in the context of AKI, studies for CKD progression are lacking (31,32). Although there is mechanistic evidence that individuals with DKD have renal tubular cell overexpression of IL-18 and although studies in patients who are HIV positive show increased eGFR progression with uIL-18, we did not find uIL-18 to be associated with renal progression (10,33).

uKIM-1 is a transmembrane glycoprotein that is expressed in the apical membrane of proximal tubular cells in response to injury and has been associated with AKI, acute RRT, and AKI-related death (34–36). Studies assessing utility of uKIM-1 in progressive CKD have had conflicting results. A case-control study from the MESA Study cohort showed that urinary levels of KIM-1 were associated with incident CKD and rapid renal function decline (11). Conversely, in another study of 260 Pima Indians with diabetes followed for 14 years, uKIM-1-to-creatinine ratio did not have any association with incident ESRD or all-cause mortality (37). Another case-control study showed no significant association of uKIM-1 levels with incident CKD stage 3 in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (38). Similarly, we did not show any association with uKIM-1-to-creatinine ratio and eGFR decline in the ACCORD Trial population.

YKL-40 is a product of the chitinase 3–like 1 gene and upregulated in kidney macrophages after ischemia-reperfusion injury (39). In addition, in AKI, elevated urinary levels of YKL-40 were associated with adverse outcomes, including renal function worsening and in-hospital death (13). There are limited data regarding the association of uYKL-40 and eGFR decline in patients with T2D. In a small study of 82 patients from The Netherlands, although uYKL-40 was part of a large multimarker panel that improved prediction for DKD worsening, it was not individually associated with eGFR decline (40). Similarly, we did not find any significant associations between urinary YKL-40 levels and the renal outcome in the ACCORD Trial. Although there may be a suggestion of a nonlinear relationship with the outcome, power was lacking to evaluate this further.

This study should be interpreted in the light of some limitations. There was significant storage time of up to 14 years between sample collection and biomarker assessment. Although they were all stored at −80°C, there are limited data on the stability of these analytes at this temperature. We cannot rule out imperfect case-control matching, although there were no significant differences between key characteristics. A large proportion of our study population was on renin-angiotensin blockers, which may affect biomarker concentrations by reducing their excretion or causing subclinical AKI (41). To minimize this, we indexed all urinary levels of biomarkers to urine creatinine concentrations as well as adjusted for ACEI/ARB use at baseline. Also, fibrate intervention has been shown to increase serum creatinine from baseline in a reversible manner (16). There were more than twice as many patients who were randomized to fibrates compared with controls. However, the estimates were robust when fibrate intervention was included in the multivariable model as a predictor variable, and in fact, association between uMCP-1-to-creatinine ratio and sustained eGFR decline was strengthened. eGFR values were calculated from serum creatinine measurements; however, direct measurement of GFR in large cohort studies is not practical. Because the participants had to survive to 24 months to have baseline and follow-up biospecimens, we cannot rule out an immortal time bias in the initial selection of 3270 participants with baseline and follow-up specimens, although this is likely to be minimal considering the low cumulative incidence of mortality. Finally, we selected inflammation, injury, and fibrosis markers that were compatible to be assayed on a single Mesoscale chip and thus, did not measure other urinary markers. Strengths of this study include the use of novel biomarkers assessing varying axes of renal decline, large number of cases and controls with preserved baseline renal function, and choice of a clinically relevant outcome.

In conclusion, urinary concentrations of uMCP-1-to-creatinine ratio were associated with sustained eGFR decline of ≥40% and added to risk prediction beyond that conferred by traditional markers. Additional studies are needed to determine whether uMCP-1 is associated with renal outcomes in other diabetic populations as well as its utility when added to other blood/urine prognostic biomarkers.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

G.N.N. is supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant T32-DK007757. C.R.P. is supported by NIH grant K24-DK090203 and NIH P30-DK079310-07 O’Brien Center Grant. C.R.P and S.G.C are supported, in part, by Chronic Kidney Disease Biomarker Consortium grant 1U01DK106962-01. This research was supported by National Institute of Diabetes Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant R01DK096549 (to S.G.C.). The Action to Control Cardiovascular Disease Trial was supported by contracts N01-HC-95178, N01-HC-95179, N01-HC-95180, N01-HC-95181, N01-HC-95182, N01-HC-95183, N01-HC-95184, IAA-Y1-HC-9035, and IAA-Y1-HC-1010 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; other components of the NIH, including the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Eye Institute; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and General Clinical Research Centers. C.R.P. is a named coinventor on the IL-18 patent.

This work was presented at the American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week in San Diego, California, November 3–8, 2015.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.12051115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.de Boer IH, Rue TC, Hall YN, Heagerty PJ, Weiss NS, Himmelfarb J: Temporal trends in the prevalence of diabetic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 305: 2532–2539, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lu Y, Singh GM, Cowan MJ, Paciorek CJ, Lin JK, Farzadfar F, Khang Y-H, Stevens GA, Rao M, Ali MK, Riley LM, Robinson CA, Ezzati M; Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases Collaborating Group (Blood Glucose) : National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: Systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2·7 million participants. Lancet 378: 31–40, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afkarian M, Sachs MC, Kestenbaum B, Hirsch IB, Tuttle KR, Himmelfarb J, de Boer IH: Kidney disease and increased mortality risk in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 302–308, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunkler D, Gao P, Lee SF, Heinze G, Clase CM, Tobe S, Teo KK, Gerstein H, Mann JF, Oberbauer R, ONTARGET and ORIGIN Investigators: Risk prediction for early CKD in type 2 diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1371–1379, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Araki S, Haneda M, Sugimoto T, Isono M, Isshiki K, Kashiwagi A, Koya D: Factors associated with frequent remission of microalbuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 54: 2983–2987, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nosadini R, Velussi M, Brocco E, Bruseghin M, Abaterusso C, Saller A, Dalla Vestra M, Carraro A, Bortoloso E, Sambataro M, Barzon I, Frigato F, Muollo B, Chiesura-Corona M, Pacini G, Baggio B, Piarulli F, Sfriso A, Fioretto P: Course of renal function in type 2 diabetic patients with abnormalities of albumin excretion rate. Diabetes 49: 476–484, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, Goff DC Jr., Bigger JT, Buse JB, Cushman WC, Genuth S, Ismail-Beigi F, Grimm RH Jr., Probstfield JL, Simons-Morton DG, Friedewald WT; Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group : Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 358: 2545–2559, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Titan SM, Vieira JM Jr., Dominguez WV, Moreira SRS, Pereira AB, Barros RT, Zatz R: Urinary MCP-1 and RBP: Independent predictors of renal outcome in macroalbuminuric diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Complications 26: 546–553, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verhave JC, Bouchard J, Goupil R, Pichette V, Brachemi S, Madore F, Troyanov S: Clinical value of inflammatory urinary biomarkers in overt diabetic nephropathy: A prospective study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 101: 333–340, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shlipak MG, Scherzer R, Abraham A, Tien PC, Grunfeld C, Peralta CA, Devarajan P, Bennett M, Butch AW, Anastos K, Cohen MH, Nowicki M, Sharma A, Young MA, Sarnak MJ, Parikh CR: Urinary markers of kidney injury and kidney function decline in HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 61: 565–573, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peralta CA, Katz R, Bonventre JV, Sabbisetti V, Siscovick D, Sarnak M, Shlipak MG: Associations of urinary levels of kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1) and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) with kidney function decline in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am J Kidney Dis 60: 904–911, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Żurawska-Płaksej E, Ługowska A, Hetmańczyk K, Knapik-Kordecka M, Adamiec R, Piwowar A: Proteins from the 18 glycosyl hydrolase family are associated with kidney dysfunction in patients with diabetes type 2. Biomarkers 20: 52–57, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall IE, Stern EP, Cantley LG, Elias JA, Parikh CR: Urine YKL-40 is associated with progressive acute kidney injury or death in hospitalized patients. BMC Nephrol 15: 133, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coresh J, Turin TC, Matsushita K, Sang Y, Ballew SH, Appel LJ, Arima H, Chadban SJ, Cirillo M, Djurdjev O, Green JA, Heine GH, Inker LA, Irie F, Ishani A, Ix JH, Kovesdy CP, Marks A, Ohkubo T, Shalev V, Shankar A, Wen CP, de Jong PE, Iseki K, Stengel B, Gansevoort RT, Levey AS; CKD Prognosis Consortium : Decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate and subsequent risk of end-stage renal disease and mortality. JAMA 311: 2518–2531, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Seaghdha CM, Hwang S-J, Larson MG, Meigs JB, Vasan RS, Fox CS: Analysis of a urinary biomarker panel for incident kidney disease and clinical outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1880–1888, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mychaleckyj JC, Craven T, Nayak U, Buse J, Crouse JR, Elam M, Kirchner K, Lorber D, Marcovina S, Sivitz W, Sperl-Hillen J, Bonds DE, Ginsberg HN: Reversibility of fenofibrate therapy-induced renal function impairment in ACCORD type 2 diabetic participants. Diabetes Care 35: 1008–1014, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Greene T, Zhang YL, Beck GJ, Froissart M, Hamm LL, Lewis JB, Mauer M, Navis GJ, Steffes MW, Eggers PW, Coresh J, Levey AS: Comparative performance of the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) and the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study equations for estimating GFR levels above 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Am J Kidney Dis 56: 486–495, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, Kausz AT, Levin A, Steffes MW, Hogg RJ, Perrone RD, Lau J, Eknoyan G; National Kidney Foundation : National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med 139: 137–147, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferenbach D, Kluth DC, Hughes J: Inflammatory cells in renal injury and repair. Semin Nephrol 27: 250–259, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanasaki K, Taduri G, Koya D: Diabetic nephropathy: The role of inflammation in fibroblast activation and kidney fibrosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 4: 7, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tesch GH: MCP-1/CCL2: A new diagnostic marker and therapeutic target for progressive renal injury in diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F697–F701, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rovin BH, Rumancik M, Tan L, Dickerson J: Glomerular expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in experimental and human glomerulonephritis. Lab Invest 71: 536–542, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ihm CG, Park JK, Hong SP, Lee TW, Cho BS, Kim MJ, Cha DR, Ha H: A high glucose concentration stimulates the expression of monocyte chemotactic peptide 1 in human mesangial cells. Nephron 79: 33–37, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banba N, Nakamura T, Matsumura M, Kuroda H, Hattori Y, Kasai K: Possible relationship of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 with diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 58: 684–690, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsui T, Yamagishi S, Ueda S, Nakamura K, Imaizumi T, Takeuchi M, Inoue H: Telmisartan, an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, inhibits advanced glycation end-product (AGE)-induced monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in mesangial cells through downregulation of receptor for AGEs via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activation. J Int Med Res 35: 482–489, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanamori H, Matsubara T, Mima A, Sumi E, Nagai K, Takahashi T, Abe H, Iehara N, Fukatsu A, Okamoto H, Kita T, Doi T, Arai H: Inhibition of MCP-1/CCR2 pathway ameliorates the development of diabetic nephropathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 360: 772–777, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Camilla R, Brachemi S, Pichette V, Cartier P, Laforest-Renald A, MacRae T, Madore F, Troyanov S: Urinary monocyte chemotactic protein 1: Marker of renal function decline in diabetic and nondiabetic proteinuric renal disease. J Nephrol 24: 60–67, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bragt MCE, Plat J, Mensink M, Schrauwen P, Mensink RP: Anti-inflammatory effect of rosiglitazone is not reflected in expression of NFkappaB-related genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Endocr Disord 9: 8, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faubel S, Edelstein CL: Caspases as drug targets in ischemic organ injury. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord 5: 269–287, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parikh CR, Jani A, Melnikov VY, Faubel S, Edelstein CL: Urinary interleukin-18 is a marker of human acute tubular necrosis. Am J Kidney Dis 43: 405–414, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siew ED, Ikizler TA, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Wickersham N, Bossert F, Peterson JF, Parikh CR, May AK, Ware LB: Elevated urinary IL-18 levels at the time of ICU admission predict adverse clinical outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1497–1505, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyauchi K, Takiyama Y, Honjyo J, Tateno M, Haneda M: Upregulated IL-18 expression in type 2 diabetic subjects with nephropathy: TGF-beta1 enhanced IL-18 expression in human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 83: 190–199, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonventre JV, Yang L: Kidney injury molecule-1. Curr Opin Crit Care 16: 556–561, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parikh CR, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Garg AX, Kadiyala D, Shlipak MG, Koyner JL, Edelstein CL, Devarajan P, Patel UD, Zappitelli M, Krawczeski CD, Passik CS, Coca SG; TRIBE-AKI Consortium : Performance of kidney injury molecule-1 and liver fatty acid-binding protein and combined biomarkers of AKI after cardiac surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1079–1088, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liangos O, Perianayagam MC, Vaidya VS, Han WK, Wald R, Tighiouart H, MacKinnon RW, Li L, Balakrishnan VS, Pereira BJG, Bonventre JV, Jaber BL: Urinary N-acetyl-β-(D)-glucosaminidase activity and kidney injury molecule-1 level are associated with adverse outcomes in acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 904–912, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fufaa GD, Weil EJ, Nelson RG, Hanson RL, Bonventre JV, Sabbisetti V, Waikar SS, Mifflin TE, Zhang X, Xie D, Hsu C-Y, Feldman HI, Coresh J, Vasan RS, Kimmel PL, Liu KD; Chronic Kidney Disease Biomarkers Consortium Investigators : Association of urinary KIM-1, L-FABP, NAG and NGAL with incident end-stage renal disease and mortality in American Indians with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 58: 188–198, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhavsar NA, Köttgen A, Coresh J, Astor BC: Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) and kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1) as predictors of incident CKD stage 3: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 233–240, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt IM, Hall IE, Kale S, Lee S, He C-H, Lee Y, Chupp GL, Moeckel GW, Lee CG, Elias JA, Parikh CR, Cantley LG: Chitinase-like protein Brp-39/YKL-40 modulates the renal response to ischemic injury and predicts delayed allograft function. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 309–319, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pena MJ, Heinzel A, Heinze G, Alkhalaf A, Bakker SJL, Nguyen TQ, Goldschmeding R, Bilo HJG, Perco P, Mayer B, de Zeeuw D, Lambers Heerspink HJ: A panel of novel biomarkers representing different disease pathways improves prediction of renal function decline in type 2 diabetes. PLoS One 10: e0120995, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nielsen SE, Rossing K, Hess G, Zdunek D, Jensen BR, Parving H-H, Rossing P: The effect of RAAS blockade on markers of renal tubular damage in diabetic nephropathy: u-NGAL, u-KIM1 and u-LFABP. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 72: 137–142, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.