Abstract

Adipose lesions rarely affect the peripheral nerves. This can occur in two different ways: Direct compression by an extraneural lipoma, or by a lipoma originated from the adipose cells located inside the nerve. Since its first description, many terms have been used in the literature to mention intraneural lipomatous lesions. In this article, the authors report a case of a 62-year-old female who presented with an intraneural median nerve lipoma and review the literature concerning the classification of adipose lesions of the nerve, radiological diagnosis and treatment.

Key words: Carpal tunnel syndrome, lipoma, median nerve, peripheral nerves

Introduction

Adipose tumors are the most common soft tissue tumor of nonneural origin in the body,[1,2] with predominance in females and higher incidence during the fourth and fifth decades.[3] It is estimated that the annual incidence of lipoma is about 1 case/1,000 people.[4] These lesions are most commonly located in the trunk, shoulder, upper arm, and neck, but they are unusual in the hand and foot. In the hand, lipomas account for <5% of benign tumors.[5]

Despite very prevalent, lipomas rarely affect the peripheral nerves.[6] This can occur in two different ways: Direct compression by an extraneural lipoma, or by an intraneural lipoma originated from the adipose cells located inside the nerve. Intraneural lipomas are quite rare with few case reports and small series reported in the literature.[6] Furthermore, the nomenclature for these lesions is confusing, with many terms being used over the years.[7]

The objectives of this paper are to report a case of an intraneural lipoma of the median nerve mimicking carpal tunnel syndrome and to review the literature concerning the current classification of adipose tumors involving the peripheral nerves, pathology, and treatment of these lesions.

Case Report

A 62-year-old female presented at our institution with a history of an enhancing subcutaneous mass on the right hand over the past 10 years. Over the last 3 years, she experienced episodes of moderate pain and paraesthesias on the first and second fingers. She had no medical history and had no history of hand trauma. Physical exam identified a 3 cm long subcutaneous tumor on the center of the right palmar region, with a hard consistency on palpation, slightly mobile for lateral movement [Figure 1a]. Neurological examination revealed hypoesthesia on the first, second, and third fingers, associated with handgrip impairment due to the tumor, not for weakness. Tinel's sign was present in the wrist, proximally to the mass. No other cutaneous or soft tissue lesions were noted. Ultrasound exam performed in other institution identified a 3.0 cm × 2.6 cm hypoechoic nodular image with irregular borders. The electromyographic examination inferred carpal tunnel syndrome due to a partial conduction block of the median nerve at the wrist. Magnetic resonance image (MRI) revealed a 3.0 cm × 2.6 cm × 1.6 cm heterogeneous lesion in the palmar region attached to the median nerve [Figure 2]. The patient underwent surgical resection of the lesion. After the section of carpal ligament and exposure of the median nerve, a gross total resection of the well-encapsulated mass was achieved. The lesion was found to originate in the median nerve close to its division in the palmar region. The tumor was stuck to the lateral and medial branches, and a careful dissection was performed in order to remove the tumor in one piece without damaging to the nerve structures. Gentle interfascicular dissection was needed in the proximal part of tumor attached to the median nerve [Figure 1]. Microscopic examination revealed a uniform lesion consisting of lobules of mature adipose tissue separated by fibrocollagenous septae, without neural elements in between [Figure 3]. Immediate pain relief was reported after surgery, and no new neurological deficit was identified. On clinical examination 2 years after surgery, the patient was free from hypoesthesia and paresthesia, with no evidence of tumor recurrence.

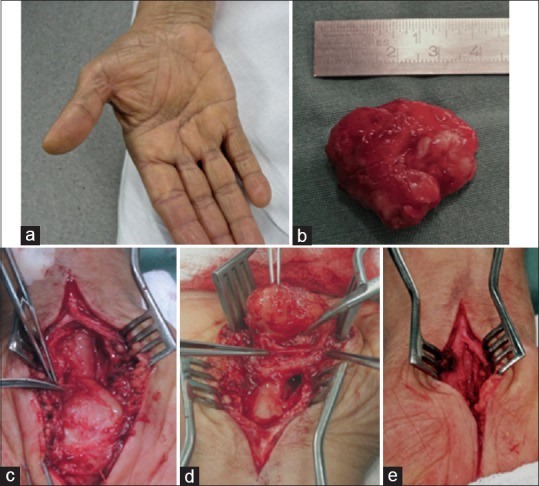

Figure 1.

A 62-year-old female presented with an enhancing subcutaneous mass on the right palmar region over 10 years (a). She experienced pain and paraesthesias on the first and second fingers. Neurological examination revealed hypoesthesia on the first, second, and third fingers, as well as Tinel's sign. The patient underwent surgical resection of a well-encapsulated mass that was found to originate in the median (b-e)

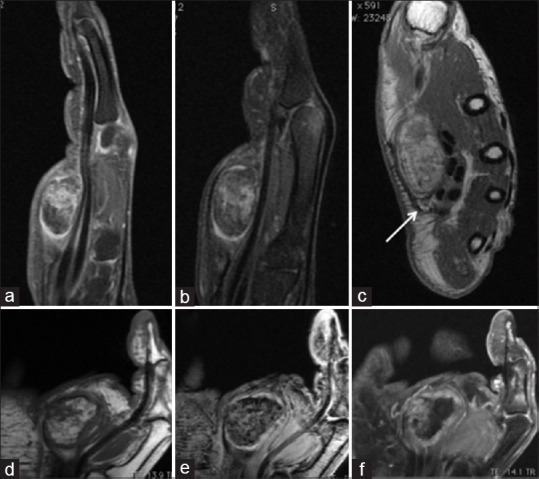

Figure 2.

Hand magnetic resonance image demonstrating the well-encapsulated fatty-fibrous tumor of the median nerve. Sagittal T1-weighted with gadolinium (a) and fat suppression (b) demonstrating the relationship with the palmar tendons. Axial T1-weighted (c) demonstrating the heterogeneous mass attached to the median nerve (arrow). Coronal T1 (d) demonstrates similar fat signal of the hipotenar region complemented with coronal T2 gradient echo (e) and T1 with gadolinium (f)

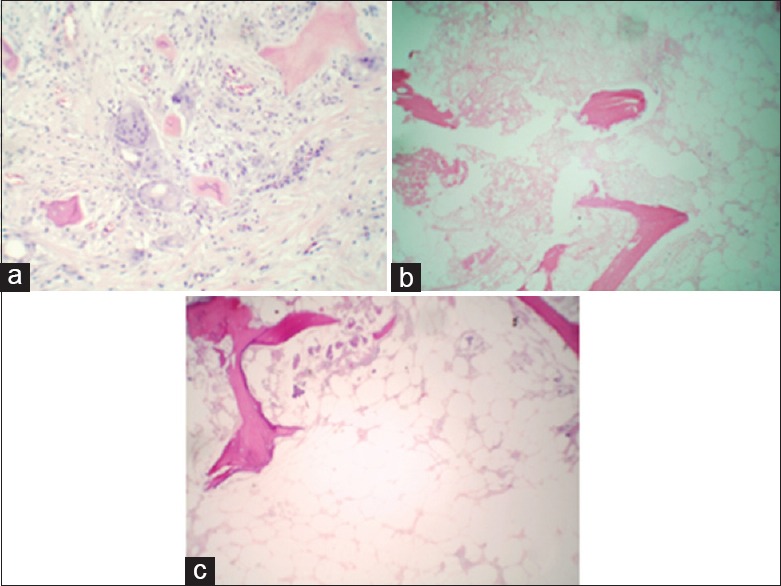

Figure 3.

Histopathology demonstrates mature adipose tissue with fibrosis, necrosis, and some areas of ossification (a: H and E, ×400; b: H and E, ×100; c: H and E, ×200)

Discussion

There is two broad of categories of tumors that can cause nerve compression: Tumors with a neural sheat origin and those with nonneural sheat origin. The formers are much more frequent and are represented by schwannomas, neurofibromas and malignant peripheral nerve sheat tumors. In the experience of 30 years of Gosk et al.,[8] the authors reported 101 nerve tumors in 94 patients, 8 of them had nonneural sheat origin. Kim et al.[9] reviewed their experience with 146 nonneural nerve sheat tumors and reported that 113 were benign. Adipose tumors accounted for 11% of all lesions (12 lipomas and 4 lipomatosis of nerve). Other etiologies of benign lesions included ganglion cyst (33), localized hyperthophic neuropathy (16), tumor of vascular origin (12), desmoid tumor (11), myositis ossifications (4), osteochondroma (4), ganglioneuroma (4), meningioma (2), cystic hygroma (2), myoblastoma (2), granular cell tumor (2), triton tumor (2), lymphangioma (2) and epidermoid cyst (1).

Adipose cells are normal constituent of peripheral nerve, wherein they reside in epineurum between fascicles. However, lipomatous tumors that arise in the peripheral nerves are extremely rare. The first description of an intraneural lipoma was done by Morley in 1964.[10] Since its description, many terms have been used to refer to lipomatous tumors involving peripheral nerves such as intraneural lipomas, neural fibrolipoma, libofibromatous hamartoma, perineural lipoma, macrodystrophia lipomatosa, lipomatosis of nerve, extraneural lipomas compressing the nerves.

In 1978, Terzis et al. classified benign adipose tumors of the peripheral nerves into three types: Well-encapsulated intraneural lipomas, diffusely infiltrating fibrofatty tumors (lipofibromatous hamartomas), and macrodystrophia lipomatosa.[11] In 1994, Guthikonda et al. reviewed this classification and proposed that the peripheral nerves can be affected by lipomatous tumors in four different ways: (1) Soft lipoma, when a solitary subcutaneous or deep-located (in the subfascial or muscular planes) lipoma compresses the nerve causing symptoms; (2) intraneural lipoma, referred by an encapsulated and clearly defined tumor occurring within the nerve, easily resecable with partial interfascicular dissection; (3) lipofibromatous hamartoma, a condition characterized by an enormous diffuse swelling of a major nerve due to dense infiltration of the nerve by fibrofatty tissue not easily separable from the fascicles; and (4) macrodystrophia lipomatosa, a lesion characterized by a diffuse enlargement of the digits due to the fatty infiltration or hypertrophy of all components of the digit, including skin, subcutaneous tissue, bone, and nerves.[12]

In 2002, The World Health Organization's (WHO) Committee for the Classification of Soft Tissue Tumors divided benign lipomatous tumors into nine distinct diagnoses: (1) Lipoma; (2) lipomatosis; (3) lipomatosis of nerve; (4) lipoblastoma/lipoblastomatosis; (5) angiolipoma; (6) myolipoma of soft tissue; (7) chondroid lipoma; (8) spindle-cell lipoma/pleomorphic lipoma; (9) hibernoma. This system of classification recognized two newly characterized entities, myolipoma and chondroid lipoma, and acknowledged the renaming of fibrolipomatous hamartoma of nerve as lipomatosis of nerve.[13]

More recently, Spinner et al.[7] proposed a new classification for lipomatous tumors involving the peripheral nerves based on the WHO's pathologic definitions of lipoma and lipomatosis of the nerve. Their classification takes into consideration the presence of focal (lipoma) or diffuse (lipomatosis) lesion and the location of the tumor in relation to the nerve (intra- or extra-neural). Lipomatosis of nerve consists of a diffuse epineural and interfascicular of mature fatty or fibroadipose tissue, with macroscopically normally entrapped fascicles. Lipomas are focal, usually well-demarcated masses that can affect the epineurium (intraneural lipomas), or they have an extraneural origin and can cause nerve compression. The authors grouped adipose tumors into two main categories: (1) Basic lipomas or lipomatosis of nerve (either intra or extraneural); and (2) combined lesions: Combinations of intra- and extra-neural lesions, combinations of lipomas with lipomatosis, or combined intra- and extra-neural lipomas in the setting of lipomatosis.

The majority of lipomas involving the peripheral nerves were reported in the median,[2,3,5,12,14,15,16,17] radial,[18,19,20,21,22] and ulnar nerves.[23,24] There are also reports about lipomas involving the brachial plexus,[9,25] suprascapular,[26] supraclavicular,[27] posterior tibial,[28,29] and fibular nerves.[29,30] In their series of 146 nonneural nerve sheat tumors in a period of 30 years, Kim et al.[9] reviewed 16 adipose tumors involving peripheral nerves. There were 4 lipomatosis of median nerve and 12 lipomas: 4 of them involved the median nerve, followed by ulnar (2), brachial plexus (2), musculocutaneous (1), axillary (1), radial (1), and sciatic (1).

Due to their slow-growing nature, adipose lesions of nerve usually present as asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic swelling.[3] Severe nerve dysfunction is seldom reported in nerve lipomas.[12] Median nerve lipoma should be suspected in patients with unilateral carpal tunnel syndrome and nerve conduction abnormalities.[16] Carpal tunnel syndrome is known to be idiopathic and to occur bilaterally and in the majority of cases. Nakamichi and Tachibana reported an increased prevalence of space-occupying lesions in patients with unilateral carpal tunnel syndrome.[31] Bagatur and Yalcinkaia reported two cases of occult palmar lipomas causing median nerve compression in patients with unilateral carpal tunnel syndrome.[16]

MRI is the visualization modality of choice for explorations of tumors of the hand. Examining a series of 134 cases of hand and wrist tumors, Capelastegui et al. compared MRI with histopathological findings and concluded that MRI has a positive predictive value of 94%.[32] Classically, adipose tumors appear as a homogeneous mass, with sharp border, high signal intensity in T1 and T2, reduced signal intensity after erasure of the fat signal, and no enhancement using the gadolinium contrast agent.[33,34] Heterogeneous signal can be observed in lesions with fibrous component, as observed in our case. MRI is the best noninvasive exam to differentiate intraneural lipomas from lipomatosis of nerve and other lesions involving the peripheral nerves. In MRI lipomatosis of nerve appears as a diffuse enlargement of the affected nerve, with fatty and fibrous infiltration causing cable-like or spaghetti-like appearance of the thickened fascicles.[35] Besides, it is helpful to planning surgery once it shows the extent of the tumor and its relation to important structures.[36] Some authors have recently described their experience with ultrasonography in the diagnosis and intraoperative management of peripheral nerve lesions.[37,38] The method can be used for refining the localization of the normal and pathological anatomy, being particularly useful in cases of multiple lesions, small lesions, deep or difficult-to-localize nerves, and in previously operated or traumatized regions.[37] As mentioned by Haldeman et al.,[37] it is expected that in near future the improvements of high-resolution ultrasonography can be used to define not only the nerves and pathology but also the intraneural anatomy to improve results of nerve tumors.

Intraneural lipomas are encapsulated epineural masses that displace rather than surround nerve fascicles. In some cases, partial interfascicular dissection is required for complete removal of intraneural lipomas.[3] This was needed in 1 of 12 lipomas reported by Kim et al.[9] Surgical resection of the lipoma is generally safe and effective in reducing neuropathic symptoms. The risks of surgery relate largely to the location and size of the tumor, including contractures, infection, nerve damage, scar sensitivity, and complex regional pain syndrome.[1] In their series of eight adipose tumors involving the peripheral nerves, Flores and Carneiro reported a patient who developed a clinical picture of sympathetic reflex dystrophy after resection of a median nerve lipoma.[6] Significant involvement of fatty-fibrous mass within the nerve is observed in cases of lipomatosis of nerve. Because of the severe neural involvement, the usual surgical management involves just nerve decompression rather than an attempt to remove the tumor. Kim et al.[9] reported four cases of lipomatosis of the median nerve and the treatment consisted of section of carpal ligament and nerve decompression.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cribb GL, Cool WP, Ford DJ, Mangham DC. Giant lipomatous tumours of the hand and forearm. J Hand Surg Br Eur Vol. 2005;30:509–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amadio PC, Reiman HM, Dobyns JH. Lipofibromatous hamartoma of nerve. J Hand Surg Am. 1988;13:67–75. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(88)90203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gennaro S, Merciadri P, Secci F. Intraneural lipoma of the median nerve mimicking carpal tunnel syndrome. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2012;154:1299–301. doi: 10.1007/s00701-012-1303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rydholm A, Berg NO. Size, site and clinical incidence of lipoma. Factors in the differential diagnosis of lipoma and sarcoma. Acta Orthop Scand. 1983;54:929–34. doi: 10.3109/17453678308992936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jalan D, Garg B, Marimuthu K, Kotwal P. Giant lipoma: An unusual cause of carpal tunnel syndrome. Pan Afr Med J. 2011;9:29. doi: 10.4314/pamj.v9i1.71205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flores LP, Carneiro JZ. Peripheral nerve compression secondary to adjacent lipomas. Surg Neurol. 2007;67:258–62. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2006.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spinner RJ, Scheithauer BW, Amrami KK, Wenger DE, Hébert-Blouin MN. Adipose lesions of nerve: The need for a modified classification. J Neurosurg. 2012;116:418–31. doi: 10.3171/2011.8.JNS101292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gosk J, Gutkowska O, Mazurek P, Koszewicz M, Ziólkowski P. Peripheral nerve tumours: 30-year experience in the surgical treatment. Neurosurg Rev. 2015;38:511–20. doi: 10.1007/s10143-015-0620-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, Moes G, Kline DG. A series of 146 peripheral non-neural sheath nerve tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:256–66. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.2.0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morley GH. Intraneural lipoma of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel. Report of a case. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1964;46:734–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terzis JK, Daniel RK, Williams HB, Spencer PS. Benign fatty tumors of the peripheral nerves. Ann Plast Surg. 1978;1:193–216. doi: 10.1097/00000637-197803000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guthikonda M, Rengachary SS, Balko MG, van Loveren H. Lipofibromatous hamartoma of the median nerve: Case report with magnetic resonance imaging correlation. Neurosurgery. 1994;35:127–32. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199407000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fletcher CD. The evolving classification of soft tissue tumours – An update based on the new 2013 WHO classification. Histopathology. 2014;64:2–11. doi: 10.1111/his.12267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein LJ, Helfend LK, Kordestani RK. Postoperative edema after vascular access causing nerve compression secondary to the presence of a perineuronal lipoma: Case report. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:412–3. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200202000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Babins DM, Lubahn JD. Palmar lipomas associated with compression of the median nerve. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:1360–2. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199409000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bagatur AE, Yalcinkaya M. Unilateral carpal tunnel syndrome caused by an occult palmar lipoma. Orthopedics. 2009;32 doi: 10.3928/01477447-20090818-20. pii: Orthosupersite.com/view.asp?rID= 43775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okubo T, Saito T, Mitomi H, Takagi T, Torigoe T, Suehara Y, et al. Intraneural lipomatous tumor of the median nerve: Three case reports with a review of literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3:407–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balakrishnan A, Chang YJ, Elliott DA, Balakrishnan C. Intraneural lipoma of the ulnar nerve at the elbow: A case report and literature review. Can J Plast Surg. 2012;20:e42–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzgerald A, Anderson W, Hooper G. Posterior interosseous nerve palsy due to parosteal lipoma. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:535–7. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2002.0783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganapathy K, Winston T, Seshadri V. Posterior interosseous nerve palsy due to intermuscular lipoma. Surg Neurol. 2006;65:495–6. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henrique A. A high radial neuropathy by parosteal lipoma compression. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:386–8. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.121766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lidor C, Lotem M, Hallel T. Parosteal lipoma of the proximal radius: A report of five cases. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17:1095–7. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(09)91072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galeano M, Colonna M, Risitano G. Ulnar tunnel syndrome secondary to lipoma of the hypothenar region. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;46:83–4. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200101000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ozdemir O, Calisaneller T, Gerilmez A, Gulsen S, Altinors N. Ulnar nerve entrapment in Guyon's canal due to a lipoma. J Neurosurg Sci. 2010;54:125–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sergeant G, Gheysens O, Seynaeve P, Van Cauwelaert J, Ceuppens H. Neurovascular compression by a subpectoral lipoma. A case report of a rare cause of thoracic outlet syndrome. Acta Chir Belg. 2003;103:528–31. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2003.11679484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hazrati Y, Miller S, Moore S, Hausman M, Flatow E. Suprascapular nerve entrapment secondary to a lipoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;411:124–8. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000063791.32430.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zvijac JE, Sheldon DA, Schürhoff MR. Extensive lipoma causing suprascapular nerve entrapment. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2003;32:141–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen WS. Lipoma responsible for tarsal tunnel syndrome. Apropos of 2 cases. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1992;78:251–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Resende LA, Silva MD, Kimaid PA, Schiavão V, Zanini MA, Faleiros AT. Compression of the peripheral branches of the sciatic nerve by lipoma. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1997;37:251–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vasudevan JM, Freedman MK, Beredjiklian PK, Deluca PF, Nazarian LN. Common peroneal entrapment neuropathy secondary to a popliteal lipoma: Ultrasound superior to magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosis. PM R. 2011;3:274–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamichi K, Tachibana S. Unilateral carpal tunnel syndrome and space-occupying lesions. J Hand Surg Br. 1993;18:748–9. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(93)90236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Capelastegui A, Astigarraga E, Fernandez-Canton G, Saralegui I, Larena JA, Merino A. Masses and pseudomasses of the hand and wrist: MR findings in 134 cases. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28:498–507. doi: 10.1007/s002560050553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ergun T, Lakadamyali H, Derincek A, Tarhan NC, Ozturk A. Magnetic resonance imaging in the visualization of benign tumors and tumor-like lesions of hand and wrist. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2010;39:1–16. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goodwin RW, O'Donnell P, Saifuddin A. MRI appearances of common benign soft-tissue tumours. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:843–53. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahlawat S, Chhabra A, Blakely J. Magnetic resonance neurography of peripheral nerve tumors and tumorlike conditions. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2014;24:171–92. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pagonis T, Givissis P, Christodoulou A. Complications arising from a misdiagnosed giant lipoma of the hand and palm: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:552. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haldeman CL, Baggott CD, Hanna AS. Intraoperative ultrasound-assisted peripheral nerve surgery. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E4. doi: 10.3171/2015.6.FOCUS15232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee FC, Singh H, Nazarian LN, Ratliff JK. High-resolution ultrasonography in the diagnosis and intraoperative management of peripheral nerve lesions. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:206–11. doi: 10.3171/2010.2.JNS091324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]