Abstract

RNA helicases play fundamental roles in modulating RNA structures and facilitating RNA-protein (RNP) complex assembly in vivo. Previously, our laboratory demonstrated that the DEAD-box RNA helicase Dbp2 in S. cerevisiae is required to promote efficient assembly of the co-transcriptionally associated mRNA binding proteins Yra1, Nab2, and Mex67 onto poly(A) + RNA. We also found that Yra1 associates directly with Dbp2 and functions as an inhibitor of Dbp2-dependent duplex unwinding, suggestive of a cycle of unwinding and inhibition by Dbp2. To test this, we undertook a series of experiments to shed light on the order of events for Dbp2 in co-transcriptional mRNP assembly. We now show that Dbp2 is recruited to chromatin via RNA and forms a large, RNA-dependent complex with Yra1 and Mex67. Moreover, single molecule (smFRET) and bulk biochemical assays show that Yra1 inhibits unwinding in a concentration-dependent manner by preventing the association of Dbp2 with single-stranded RNA. This inhibition prevents over-accumulation of Dbp2 on mRNA and stabilization of a subset of RNA Pol II transcripts. We propose a model whereby Yra1 terminates a cycle of mRNP assembly by Dbp2.

Keywords: DEAD-box, helicase, RNA-Protein complex, chromatin, RNA

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Gene expression is an extremely complex process that involves numerous, highly choreographed steps [1]. During transcription in eukaryotes, the newly synthesized messenger RNA (mRNA) undergoes a variety of intimately linked processing events, including 5’ capping, splicing, and 3’ end formation, prior to nuclear export and translation [1–3]. Throughout each of these steps, the mRNA is bound by RNA-binding proteins to form messenger ribonucleoprotein complexes (mRNP), the composition of which is constantly changing at each maturation stage [4]. Proper mRNP formation is critical for gene expression and requires correctly structured mRNA at the appropriate biological time point [2,5]. Given their physical properties, RNA molecules tend to form stable secondary structures that are long-lived and require large amounts of energy to unfold and refold to alternative conformations [6,7]. This results in a need for proteins to accelerate RNA structural conversions inside the cell. In the budding yeast S. cerevisiae, mRNA appears to be largely unstructured in vivo, in contrast to thermodynamic predictions [2], suggesting the involvement of active mechanisms to prevent formation of aberrant structures. Consistently, ATP-depletion in budding yeast results in increased formation of secondary structure in mRNA [2]. Moreover, recent genome wide analyses of mRNA secondary structure have found a striking correlation between single nucleotide polymorphisms and altered RNA structure within regulatory regions (i.e. miRNA-binding sites), indicating that structural aberrations may alter gene regulation [8,9].

Likely candidates for structural rearrangement of cellular mRNAs are ATP-dependent RNA helicases, which act as RNA unwinding or RNA-protein (RNP) remodeling enzymes [10,11]. DEAD-box proteins make up the largest class of enzymes in the RNA helicase family with around 40 members in human cells (25 in yeast). Members of this class are ubiquitously present in all domains of life from bacteria to mammals and are involved in every aspect of RNA metabolism, including pre-mRNP assembly [12]. For example, alternative splicing of the pre-mRNA that encodes the human Tau protein is regulated by a stem-loop structure downstream of the 5’ splice site of exon 10 [13]. In order for U1 snRNP to access the 5’ splice site of tau exon 10, this stem-loop needs to be resolved by the DEAD-protein DDX5 [13]. Mis-regulation of splicing in the tau gene is highly associated with dementia, underscoring the importance of remodeling for proper gene expression [14,15]. However, our understanding of the biochemical mechanism(s) of pre-mRNA/mRNA remodeling has been hampered due to the complex and highly interdependent nature of co-transcriptional processes. Moreover, individual DEAD-box protein family members exhibit a wide variety of biochemically distinct activities including RNA annealing, nucleotide sensing, and RNP remodeling, with further diversification of biological functions conferred by regulatory accessory proteins [11,16–18]

The S. cerevisiae ortholog of DDX5 is Dbp2 [19]. Our laboratory has previously established that Dbp2 is an active ATPase and RNA helicase that associates with transcribing chromatin [17,20]. Moreover, Dbp2 is required for assembly of the mRNA binding proteins Yra1 and Nab2, as well as the mRNA export receptor Mex67, onto mRNA [17]. Interestingly, Yra1 interacts directly with Dbp2 and this interaction inhibits Dbp2 unwinding in multiple cycle, bulk assays, demonstrating that Yra1 restricts unwinding by Dbp2 [17]. Nevertheless, the mechanism and the biological role of Yra1-dependent inhibition were not understood.

By utilizing a combination of biochemical, molecular biology and biophysical methods, we now provide compelling evidence that Yra1 constrains the activity of Dbp2 to co-transcriptional mRNP assembly steps. This inhibition is important for maintenance of transcript levels in vivo. Single molecule (sm) FRET and fluorescence anisotropy studies show that Yra1 inhibits Dbp2 unwinding by preventing association of Dbp2 with RNA. Consistently, loss of the Yra1-Dbp2 interaction in yeast cells causes post-transcriptional accumulation of Dbp2 on mRNA. Taken together, this suggests that Yra1 terminates a cycle of Dbp2-dependent mRNP assembly in vivo.

Results

Dbp2 is recruited to chromatin via nascent RNA

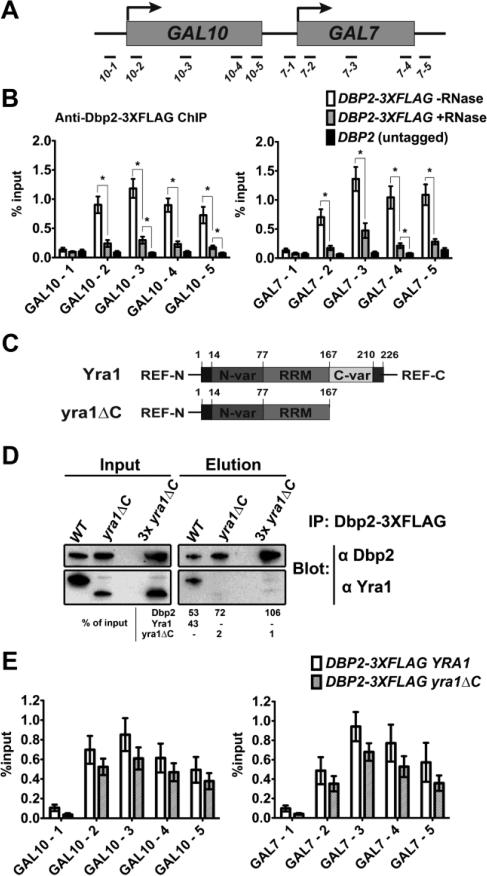

The DEAD-box RNA helicase Dbp2 is predominately localized in the nucleus in association with actively transcribed genes [20–23]. To determine if Dbp2 is recruited to chromatin via nascent RNA, we conducted chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays with or without RNase treatment [24]. Briefly, yeast cells harboring a 3XFLAG epitope tag fused to the 3’ end of the endogenous DBP2 coding region were grown in the presence of galactose to induce transcription of the GAL genes, known gene targets for Dbp2 association [17]. DBP2 untagged strains were used to serve as a background control. Chromatin was then isolated and incubated with a mixture of RNase A and RNase I or buffer alone prior to ChIP with the anti-FLAG antibody. The eluted fractions were then subjected to quantitative (q)PCR with probes across the GAL10 and GAL7 genes (Fig. 1A). Consistent with previous studies, this revealed that Dbp2 is evenly distributed across the coding regions of both GAL10 and GAL7 with little to no association with promoters (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, RNase treatment drastically reduced Dbp2 occupancy across the entire locus for both the GAL10 and GAL7 genes (Fig.1B). This suggests that Dbp2 is recruited to chromatin by interacting with newly transcribed RNA. The low level of RNase-resistant Dbp2 could be due to trace amounts of RNA still present after enzymatic digestion or an alternative recruitment mechanism, such as interaction with RNA Polymerase II (RNA Pol II).

Figure 1. Dbp2 is recruited to chromatin via RNA.

(A) Schematic diagram of the GAL10 and GAL7 genes and the positions of qPCR amplicons. (B) Dbp2 is recruited to chromatin in an RNA-dependent manner. Transcription of the GAL genes was induced by growing yeast cells in rich media plus glucose initially and subsequently shifting to media with galactose for 5 hours. Chromatin was then isolated, sheared by sonication, and incubated with 7.5 U RNase A and 300 U RNase I or buffer alone before being subjected to ChIP using anti-FLAG antibodies. Results are shown as the percent of precipitated DNA over input averaged across four biological replicates with SEM. * indicates a p-value < 0.05 as assessed by student's t-test. (C) Diagram of the functional motifs of Yra1 [22,25,45,80]. The C-terminal half of Yra1 interacts with Dbp2 in vitro [17]. (D) Dbp2 interacts with the C-terminal half of Yra1 in vivo. Immunoprecipitation assays were conducted using anti-FLAG antibodies to isolate Dbp2-3xFLAG and associated proteins from wild type or yra1ΔC strains. 10% of the lysate was used as input. Dbp2 and Yra1 were detected by Western blotting with protein-specific antibodies. Immunoprecipitated Dbp2, Yra1 and yra1ΔC were quantified by densitometry and are shown as a percentage of input. (E) Loss of the C-terminal half of Yra1 does not affect the association of Dbp2 with GAL10 (left) or GAL7 (right) genes. WT and yra1ΔC strains were used for ChIP with anti-FLAG antibody against Dbp2-3xFLAG. Student t-test was performed between full-length YRA1 and yra1ΔC strains in all primer sets. All the p-values > 0.05.

Dbp2 is required for efficient assembly of mRNA-binding proteins and export factors, including Nab2, Mex67 and Yra1, and interacts directly with the C-terminal half of Yra1 [17]. Yra1 is co-transcriptionally recruited to chromatin through interaction with Pcf11, an essential component of the cleavage and polyadenylation factor IA complex involved in 3’-end formation [25]. To determine if the Dbp2-Yra1 interaction modulates recruitment of Dbp2 to chromatin, we conducted ChIP as above in either wild type or yra1ΔC strains, the latter of which lacks the ability to associate with Dbp2 in vivo (Fig. 1C – 1D). This revealed no difference in the recruitment pattern of level of Dbp2 to the GAL10 and GAL7 genes (Fig. 1E). Thus, Yra1 does not mediate recruitment of Dbp2 to chromatin.

Yra1 prevents accumulation of Dbp2 on RNA Pol II transcripts

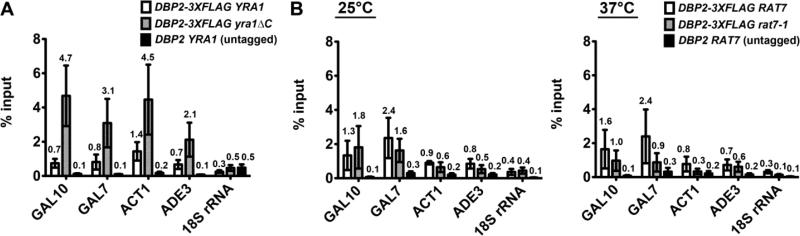

To determine if the Dbp2-Yra1 interaction modulates the association of Dbp2 with RNA, we conducted RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) of a DBP2-3XFLAG strain. Since Dbp2 associates with the GAL10, GAL7, ACT1, and ADE3 genes shown by ChIP [20], we selected these four gene transcripts as candidates whereas 18S rRNA serves as a negative control. Analysis of the levels of immunoprecipitated transcripts by RT-qPCR revealed that Dbp2 associates with all four, candidate mRNAs at levels ~7-fold above an untagged background control strain. Furthermore, loss of the Dbp2-Yra1 interaction in the yra1ΔC strain increased the association of Dbp2 with RNA Pol II transcripts by ~3 to 5-fold (Fig. 2A), suggesting that Yra1 prevents accumulation of Dbp2 on mRNA. Interestingly, the Dbp2-Yra1 interaction also affects the abundance of Dbp2 protein, with the yra1ΔC strain exhibiting two-fold more Dbp2 than wild type (Supplemental Fig. 1A). To determine if the accumulation of Dbp2 on RNA in the yra1ΔC strain is due to overexpression of DBP2, we transformed wild type cells with a 2 micron plasmid encoding DBP2 under the control of the highly active GAL1/10 promoter or with empty vector and conducted RIP as above. Under this condition, Dbp2 protein levels are at least two-fold more abundant in pGAL-DBP2 than the wild type cells with empty vector (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Furthermore, this revealed that similar amounts of the GAL10, GAL7, ACT1 and ADE3 transcripts were co-precipitated regardless of the levels of Dbp2 protein (Supplemental Fig. 1C). This suggests that the accumulation of Dbp2 on mRNA is not simply due to overexpression but is specific to the yra1ΔC strain. Furthermore, the fact that Dbp2 accumulates on RNA not chromatin (Fig. 1E) suggests this accumulation occurs after the transcript is released from the site of synthesis in yra1ΔC strains.

Figure 2. Yra1 prevents over-accumulation of Dbp2 on RNA Pol II transcripts.

(A) Dbp2 accumulates on the RNA Pol II transcripts in a yra1ΔC strain. RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assays were performed to determine the level of RNA associated with Dbp2 in wild type and isogenic yra1ΔC cells. Cells were grown with galactose to promote expression of GAL10 and GAL7 genes as in Fig. 1 and subsequently cross-linked with formaldehyde. RNPs were isolated with anti-FLAG antibodies and transcripts were detected by RT-qPCR with primers specific to the 5’ end of each mRNA (see Supplemental Table 4). Dbp2-3xFLAG occupancy on specific transcripts is shown as the average percent of isolated RNA over input for three biological replicates. Error bars indicate the SEM. (B) The association of Dbp2 with RNA Pol II transcripts is not altered in the mRNA export mutant strain, rat7-1. RIP assays were performed as above with wild type cells, isogenic rat7-1 cells [81], or isogenic, wild type untagged cells at both the permissive temperature (25°C, left) and the non-permissive temperature (37°C, right) for rat7-1 [26–28].

Prior studies have shown that loss of the C-terminal half of Yra1 results in a mild but detectible mRNA export defect [22]. To determine if the accumulation of Dbp2 on RNA is caused by a block to mRNA export, we conducted RIP in rat7-1 strains, which harbor a mutation in the NUP159 gene required for mRNA export and has been shown to induce export defects at the non-permissive temperature (37°C) [26–28]. Interestingly, this revealed slightly lower levels of Dbp2 on mRNA at the non-permissive temperature (37°C) in rat7-1 strain as compared to wild type (Fig. 2B), indicating that the accumulation of Dbp2 on mRNA is not due to a block in mRNA export.

Dbp2 is found in a large RNA-dependent complex in vivo

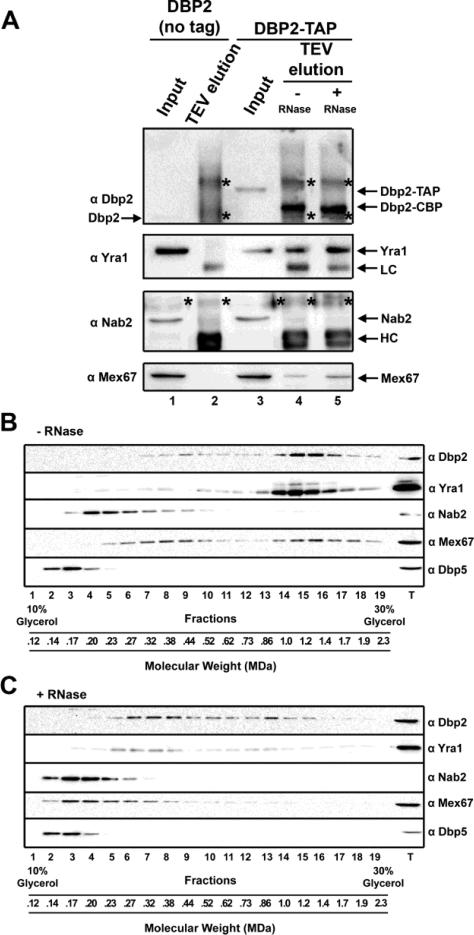

Dbp2 is necessary for efficient assembly of the RNA-binding protein Yra1, the mRNA export receptor Mex67, and the poly(A)-binding protein Nab2 with poly(A)+ RNA [17], three proteins that interact in vivo and form a trimeric complex in vitro [29]. Because Dbp2 interacts directly with Yra1, we asked if Dbp2 associates with other members of this complex in cells. To this end, we performed immunoprecipitation assays with DBP2-TAP strains with and without RNase treatment. DBP2 untagged strains serve as a background control. Though a faint band was observed at the size of Dbp2 in the elution fraction of DBP2 untagged strains (Fig. 3A, lane 2), the signal of Dbp2-CBP following TEV cleavage of the bound Dbp2-TAP [30] from DBP2-TAP strains was much stronger in either the presence or absence of RNase treatment (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 5). This suggests that Dbp2 was successfully precipitated. Consistent with in vitro studies, Yra1 was efficiently co-purified with Dbp2 regardless of RNase treatment (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 5). In addition, Mex67 was also co-purified with Dbp2 independent of RNA (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 5). This suggests that Dbp2 interacts with Yra1 and Mex67. In contrast, Nab2 did not co-purify with Dbp2 regardless of RNase treatment (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 5). To determine if these factors are present in the same complex with Dbp2 and in what proportion, we subjected wild type whole cell lysate to gradient fractionation followed by western blotting for detection of Dbp2, mRNA binding protein Yra1, Mex67, and Nab2, and the DEAD-box helicase Dbp5. Approximate molecular weights were then determined from the fractionation pattern relative to a molecular weight standard for each protein. Interestingly, Dbp2, Yra1 and Mex67 co-migrated in a large ~1.2 MDa complex, with no detectible free Dbp2 (Fig. 3B, fractions 14 – 17). This corresponds to approximately 70% of the Dbp2 and Yra1 across all fractions and 40% of Mex67. The presence of Dbp2 in a large complex is not an inherent property of DEAD-box proteins in general as the mRNA export factor and DEAD-box RNA helicase Dbp5 migrated at a significantly smaller size (Fig. 3B, fraction 2 – 4). The remaining fraction of Mex67 migrated at a smaller position corresponding to fractions 5 – 10, partially overlapping the migration pattern of Nab2 (Fig. 3B fractions 4 – 6). Approximately 3% of the total Yra1 co-migrated with Nab2 and Mex67, suggesting that the vast majority of Yra1 is also found in a large complex.

Figure 3. Dbp2 forms a large RNA-dependent complex with Yra1 and Mex67 in vivo.

(A) Mex67 and Yra1 copurify with immunoprecipitated Dbp2. TAP-tag immunoprecipitation assays of Dbp2 were conducted in the presence or absence of RNase A and RNase I. Input (1%) and elutions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and proteins were detected by western blotting. Cross-reactive heavy (HC) and light chains (LC) are noted whereas an asterisk (*) marks a nonspecific band. Note that the faster migrating band in lanes 4-5 corresponds to LC not untagged Dbp2, as there is no untagged DBP2 expressed in the haploid, DBP2-TAP strain. (B) Dbp2, Yra1 and Mex67 co-migrate as a large complex by glycerol gradient fractionation. Glycerol gradient (10 – 30%) were performed with yeast lysate and the isolated fractions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and proteins were detected by western blotting. Molecular weights were determined using a standard curve generated by resolving catalase (250 kDa), apoferritin (480 kDa), and thyroglobulin (670 kDa). (C) RNase treatment of yeast lysate prior to gradient fractionation shifts the migration pattern of Dbp2, Yra1 and Mex67. Glycerol gradient (10 – 30%) were performed as above but with RNase A and RNase I.

To determine if the migration pattern of these proteins is dependent on RNA, we subjected yeast cell lysate to RNase treatment prior to gradient fractionation. Interestingly, RNase treatment shifted the migration pattern of Dbp2, Yra1 and Mex67 to lower gradient fractions in the absence of RNA (Fig. 3C, fractions 6 – 8). Whereas the migration pattern of Nab2 was not significantly changed, Dbp2, Yra1 and Mex67 were detected across multiple smaller fractions with a larger portion of Mex67 (75%) co-fractionating with Nab2 than above (Fig. 3C, Lanes 3-6). Thus, Dbp2, Yra1 and a fraction of Mex67 form large RNA-dependent complexes in vivo. Although the precise step for Yra1-dependent inhibition is not known, this suggests that inhibition occurs during or immediately following Dbp2-dependent assembly of Yra1 and Mex67 with mRNA but prior to addition of Nab2 and subsequent mRNA export (see Discussion). This would be consistent with accumulation of Dbp2 on RNA in yra1ΔC strains (Fig. 2).

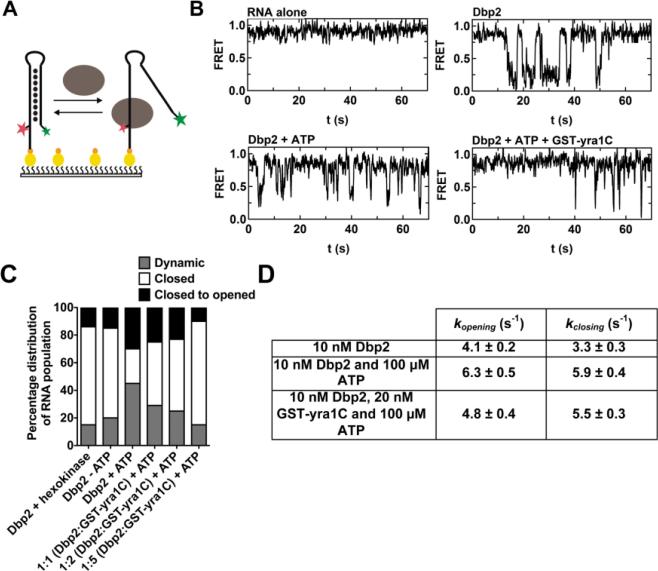

Yra1 does not alter the kinetics of Dbp2-dependent unwinding by smFRET

Our prior studies used bulk, multiple cycle assays to show that Yra1 inhibits Dbp2-dependent unwinding in vitro [17]. A limitation of these assays was the inability to distinguish between kinetic effects of Yra1 on duplex unwinding rates after association of Dbp2 or thermodynamic effects on initial binding of Dbp2 with RNA targets. To determine if Yra1 inhibits Dbp2 by decreasing the duplex unwinding rate, we first established single molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (smFRET) assays for Dbp2-dependent unwinding using a fluorescently labeled dsRNA stem-loop molecule. Although the precise substrates for Dbp2-dependent unwinding are unknown, a stem-loop is the most common secondary structure identified in cellular mRNAs to date [2,8,31,32], and, thus, represents a likely physiological target for Dbp2 in vivo.

Briefly, a 39 nt hairpin dsRNA labeled with FRET pair fluorophores Cy3 and Cy5 was surface-immobilized onto a pegylated microscope quartz slide through biotin-neutravidin linkage (Fig. 4A). The FRET pair fluorophores are close together and exhibit a high FRET state (0.9) when the dsRNA forms a closed hairpin whereas the FRET pair fluorophores are farther apart when the dsRNA is unwound with a low FRET state (0.1) (Fig. 4A). A threshold of 0.6 FRET was used to distinguish between the opened (0.1 FRET) and closed (0.9 FRET) states of the hairpin. To study Dbp2-dependent unwinding at the single molecule level, we initially established smFRET assays in the presence of low salt (30 mM NaCl) to parallel previous bulk in vitro assay experiments [17]. Under these conditions, 98% of the hairpin RNA molecules exhibit a high FRET state (0.9) in the absence of any protein or nucleotide (Supplemental Fig. 2A and Supplemental Fig. 2B), indicative of a stable dsRNA hairpin. In the presence of 10 nM Dbp2, we found that 27% showed a single transition from a closed to opened state within the course of the experiment (Supplemental Fig. 2A and Supplemental Fig. 2B). This indicates that Dbp2 can unwind a dsRNA substrate in the absence of ATP, an observation not seen in our previous in vitro bulk unwinding assays [17]. Addition of 100 μM ATP and equimolar magnesium increased the percentage of these molecules to 61%, suggesting that more molecules are acted upon by Dbp2 in the presence of ATP. This is consistent with the thermodynamic coupling of ATP and RNA-binding in DEAD-box family members [33–35]. However, we were unable to monitor the kinetics of duplex unwinding in these conditions because only ~15% of the RNA molecules exhibited dynamic cycles of opening and closing (Supplemental Fig. 2B).

Figure 4. Yra1 decreases the number of RNA hairpins unwound by Dbp2 without altering the kinetics of unwinding.

(A) Schematic representation of smFRET with a doubly-labeled hairpin RNA. Dual labeled RNA (Cy3 and Cy5) was purchased from IDT and subsequently surface-immobilized on a pegylated microscope quartz slide via biotin-neutravidin bridge (shown as yellow and orange ovals) [82]. The oval represents Dbp2. The red star represents Cy5 and the green star represents Cy3. (B) Representative FRET trajectory in the smFRET experiments. Representative trajectories of a closed RNA hairpin alone (top left), in the presence of 10 nM Dbp2 (top right),10 nM Dbp2 and 100 μM ATP (bottom left), or in the presence of 10 nM Dbp2, 20 nM yra1C, and 100 μM ATP (bottom right) are shown. (C) Yra1 decreases the number of hairpin dsRNAs unwound by Dbp2. The distribution of closed, closed to opened (single opening events), or dynamic (multiple cycles of opening and closing) hairpin dsRNAs with 10 nM Dbp2 with or without 100 μM hexokinase and 1 mM glucose in the absence of ATP or 10 nM Dbp2 with increasing concentrations of GST-yra1C in the presence of ATP are shown. Trajectories exhibiting more than one excursion into 0.2 – 0.8 FRET, i.e., opening more than once, are considered dynamic molecules. Trajectories exhibiting constant high (0.9) or low (0.1) FRET throughout the experimental time window are classified as closed or opened molecules, respectively. A threshold of 0.6 FRET was used to distinguish between the open (0.1 FRET) and close (0.9 FRET) state of the hairpin. (D) Yra1 does not appreciably alter the kinetics of Dbp2-dependent unwinding. Dwell times for each opening/closing event were measured from FRET time trajectories from dynamic dsRNA molecules. Single exponential decay was used to fit the dwell time histograms to determine kopening and kclosing respectively.

To remedy this and to make our analyses more physiologically relevant, we conducted smFRET in the presence of 150mM NaCl. The representative FRET time trajectory of RNA alone shows that the hairpin dsRNA is stable at 150 mM NaCl (Fig. 4B). This resulted in 45% of the molecules exhibiting dynamic behavior in the presence of Dbp2 and ATP, which is defined by hairpin opening more than once, whereas dsRNAs that remained closed or opened through out the trajectory, were defined as closed or opened, respectively (Fig. 4B – 4C). The increase in number of dynamic molecules was not due to a less stable RNA substrate, as the smFRET molecule remained stable throughout the timecourse (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, and consistent with our low salt studies, the addition of Dbp2 alone also resulted in dynamic cycles of opening and closing, albeit with less RNA molecules showing dynamic behavior in the absence of ATP (Fig. 4B-C). ATP-independent unwinding was not due to contaminating ATP in the Dbp2 purification as dsRNA hairpins still exhibited dynamic opening and closing cycles after treatment with hexokinase and glucose (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, smFRET studies of the mitochondrial group II intron also demonstrated an ATP-independent role for the DEAD-box protein Mss116 in RNA folding, a process that requires both folding and unwinding steps ([36] and see Discussion).

To determine if ATP alters the opening and closing rates of the RNA molecules, numerous (~100), dynamic trajectories were used to build dwell time histograms. Measurement of the dwell time distribution in the presence of Dbp2 alone (no ATP) revealed opening and closing rate constants of 4.1 s−1 and 3.3 s−1, respectively (Fig. 4D). Addition of ATP and equimolar magnesium did not appreciably increase either the opening (6.3 s−1) or closing (5.9 s−1) rates of the RNA duplex (Fig. 4D). Together, this indicates that ATP increases the population of dsRNA molecules acted upon by Dbp2.

Having established the unwinding behavior of Dbp2 after association with duplexed RNA, we then asked if Yra1 affects this behavior by incorporating a GST-tagged C-terminal half of Yra1 (yra1C) into our smFRET assays. Yra1C is the minimal Dbp2-interacting region in Yra1, which is sufficient for inhibition of helicase activity and also lacks intrinsic RNA-binding activity that would complicate experimental interpretation [17]. Interestingly, addition of a two-fold molar excess of yra1C, consistent with the ratio of Dbp2 and Yra1 proteins in yeast cells [37], did not appreciably reduce the opening (4.8 s−1) and closing (5.5 s−1) rates of the hairpin (Fig. 4D). However, yra1C did decrease the percentage of unwound molecules (both dynamic and closed to opened) across the population in a dose-dependent manner, to levels similar to Dbp2 without ATP (Fig. 4C).

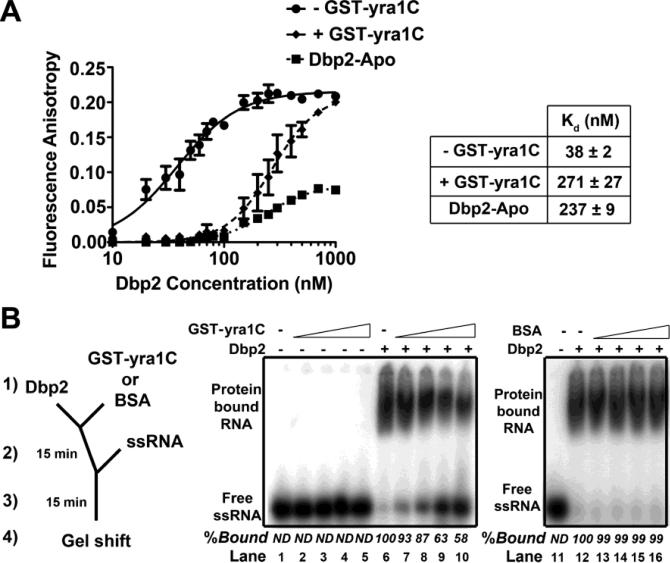

Yra1 prevents Dbp2 from associating with ssRNA in vitro

ATP promotes high RNA-binding affinity by DEAD-box proteins [38]. The population effects seen in our smFRET studies suggest that Yra1 may decrease the affinity of Dbp2 for RNA, similar to the absence of ATP. To test this, we performed fluorescence anisotropy assays with Dbp2, 6-FAM-labeled ssRNA and the pre-hydrolysis ATP analog ADP-BeFx (Fig. 5A). We also utilized low salt conditions (30 mM NaCl), as the decreased dynamics would be predicted to increase RNA-binding and the ability to form a stable complex. ADP-BeFx was also utilized to promote stable binding of Dbp2 RNA [39]. To ensure that our assays were performed under equilibrium conditions, we first conducted a time course and monitored the change in anisotropy. This showed that equilibrium is established within 100 min (Supplemental Fig. 3). Next, we conducted fluorescence anisotropy with Dbp2 in the presence or absence of ADP-BeFx. This revealed that ADP-BeFx decreased the dissociation constant (Kd) of Dbp2 for ssRNA from 237 to 38 nM (Fig. 5A), similar to other DEAD-box proteins [40,41]. Interestingly, inclusion of 150 nM yra1C increased the Kd by 7-fold to 271 nM (Fig. 5A). This suggests that Yra1 inhibits Dbp2 by reducing the affinity for RNA.

Figure 5. Yra1 reduces the RNA-binding affinity of Dbp2 in vitro.

(A) Yra1C reduces the affinity of Dbp2 for RNA. Fluorescence anisotropy assays were conducted with varying amounts of Dbp2 with or without 150 nM of GST-yra1C and 10 nM of a 16mer fluorescently labeled ssRNA (5’-6-FAM-AGC ACC GUA AAG ACG C-3’) in the presence or absence of 2 mM ADP-BeFx under equilibrium conditions. Experiments were conducted in triplicate with the average shown and error bars indicating the SEM. (B) Yra1C decreases association of Dbp2-ADP-BeFx with RNA in pre-equilibrium experiments. Gel shift assays were conducted in the presence of 2 mM ADP-BeFX/MgCl2, 10 nM of a 5’-radioactively labeled ssRNA (5’-AGC ACC GUA AAG ACG C-3’), with or without the Dbp2 (400 nM) and varying amounts of GST-yra1C or BSA (0 nM, 300 nM, 600 nM, 1200 nM, and 1800 nM). Complexes were assembled at 4°C as indicated in the schematic diagram followed by resolution on a 4% native PAGE and subsequent autoradiography. Time courses show that it takes >60 min to reach equilibrium (Supplemental Fig. 3). ND indicates the protein-bound signal was not detected.

To determine if Yra1 prevents initial RNA-binding by Dbp2, we exploited the slow on rate of the ADP-BeFx-bound Dbp2 to RNA (Supplemental Fig. 3; [39]) and asked if Yra1 reduces the association step of Dbp2 with RNA by performing an order of addition experiment under pre-equilibrium conditions for the Dbp2-ADP-BeFx-RNA complex. Briefly, Dbp2 and yra1C or BSA were pre-incubated for 15 min in the presence of ADP-BeFx followed by addition of a radiolabeled, 16 nucleotide ssRNA for an additional 15 min prior to resolution of RNA-bound complexes on a native gel (Fig. 5B). Consistent with the reduced RNA-binding affinity above (Fig. 5A), pre-incubation of Dbp2 with yra1C resulted in a concentration-dependent reduction of Dbp2 binding to ssRNA, from 100% bound to 58% (Fig. 5B, lanes 6-10). The reduction is specific to yra1C, as BSA had no effect on the RNA-binding by Dbp2 (Fig. 5B, lanes 12-16). Moreover, this is not due to competition between Yra1 and Dbp2 for RNA as yra1C does not exhibit appreciable RNA binding activity ([17] and Fig. 5B, lanes 2-5). Yra1 also reduced ssRNA binding by Dbp2 at physiological (150 mM) salt concentrations (Supplemental Fig. 4). This indicates that Yra1 inhibits the unwinding activity of Dbp2 by reducing the affinity for RNA. Because Yra1 and Dbp2 exist in a 2:1 ratio in yeast cells [37] and Yra1 prevents over accumulation of Dbp2 on cellular mRNAs (Fig. 2A), this suggests that Yra1 functions similarly in vivo.

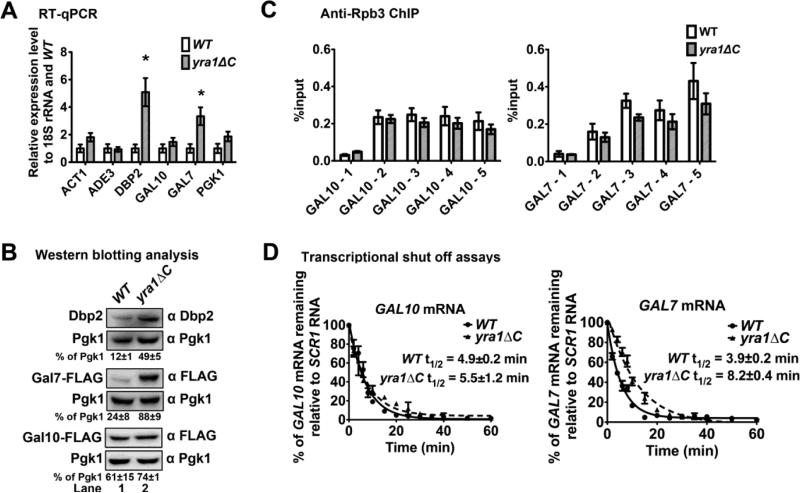

Loss of the Dbp2-Yra1 interaction increases the half-life of GAL7 mRNA

To determine if Yra1-dependent inhibition of Dbp2 is necessary for proper gene expression, we analyzed Dbp2-bound targets for expression defects in wild type and yra1ΔC strains. We also analyzed the DBP2 transcript itself since the yra1ΔC strain shows higher Dbp2 protein levels than wild type cells (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Interestingly, this revealed that both the DBP2 and GAL7 transcripts and resulting proteins are significantly upregulated in yra1ΔC strains (Fig. 6A-B). In contrast, none of the other Dbp2-associated transcripts exhibited altered abundance (Fig. 6A). We were also unable to detect a change in protein level for GAL10 (Fig. 6B). This suggests that the accumulation of Dbp2 results in a transcript-specific effect on gene expression.

Figure 6. The Dbp2-Yra1 interaction prevents overexpression of specific of gene products in vivo.

(A) Loss of the Dbp2-Yra1 interaction results in overaccumulation of GAL7 and DBP2 transcripts. Growing wild type or yra1ΔC cells with galactose induced transcription of the GAL genes. RT-qPCR was performed for the indicated genes following extraction of RNA using primers listed in Supplemental Table 4. Transcript levels were normalized to 18S rRNA and wild type. Error bars indicate the SEM from three biological replicates and * indicates a p-value <0.05 from a two tailed student t-test. (B) Loss of the Dbp2-Yra1 interaction increases protein levels of Gal7 and Dbp2. C-terminally 3X-FLAG-tagged GAL10 and GAL7 strains were constructed in the yra1ΔC strain by standard yeast methods to provide an epitope for western blotting. Protein detection by western blotting was conducted using anti-Dbp2 [23] or anti-FLAG as indicated. Protein signal intensity was quantified with ImageQuant. The average signal and SEM with respect to Pgk1 is shown for three biological replicates. (C) RNA Pol II exhibits a similar pattern of gene occupancy in both wild type and yra1ΔC strains. ChIP was performed as above, but with anti-Rpb3 antibodies, a subunit of RNA Pol II. (D) The GAL7 mRNA has a longer half-life in yra1ΔC strains than wild type cells. Transcriptional shut off assays were performed by shifting indicated strains to glucose to repress transcription of GAL genes after a 10 hours induction with galactose. RNA was extracted at the indicated time points and transcripts were detected by Northern blotting. Transcripts were quantified by densitometry and normalized to scR1. Half-lives were calculated from three, independent biological replicates by fitting the data to an exponential decay equation.

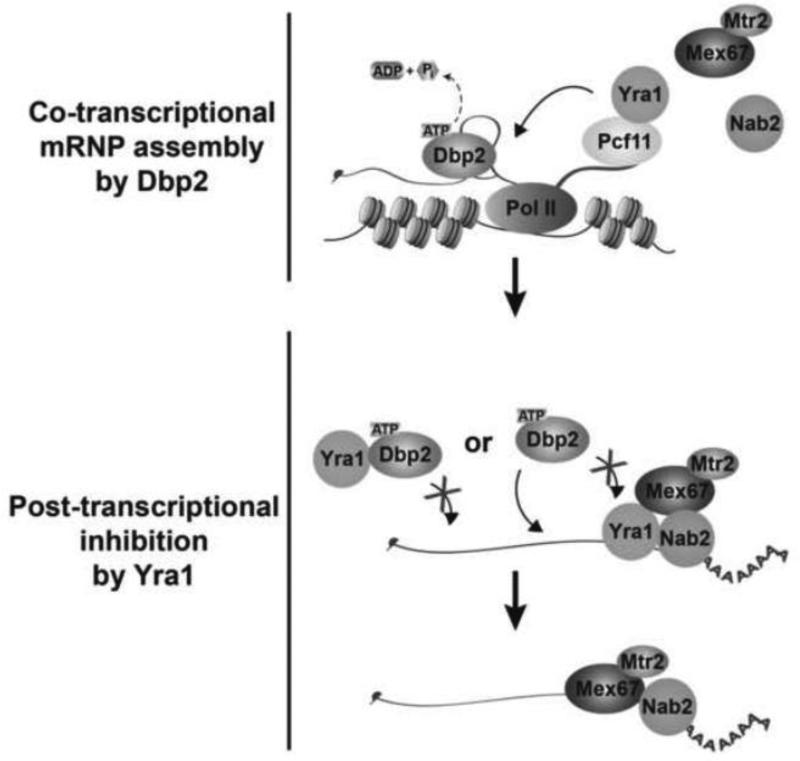

To determine the mechanism for increased GAL7 mRNA abundance in yra1ΔC strains, we asked if the increase occurred at transcription or decay. To this end, we conducted ChIP of RNA Pol II and transcriptional shut off assays to compare the transcription and mRNA decay efficiencies, respectively. ChIP using anti-Rpb3 revealed similar levels and patterns of RNA Pol II occupancy in both wild type and yra1ΔC strains across both GAL7 and GAL10, suggesting that Dbp2 accumulation does not alter transcription efficiency (Fig. 6C). In contrast, however, transcriptional shut off assays, using glucose addition to the media and subsequent northern blotting, revealed that the half-life of the GAL7 mRNA is approximately two times longer in yra1ΔC strains as compared to wild type (Fig. 6D). This was not the case for the GAL10 mRNA, whose half-life was unchanged. This suggests that Dbp2 accumulation prevents efficient degradation of a subset of transcripts. Although it is currently unclear what renders GAL7 mRNAs sensitive to Dbp2 accumulation, it is likely that this specificity is dictated by the mRNA sequence and/or structure itself. Regardless, this demonstrates that Yra1-dependent inhibition of Dbp2 alters mRNA metabolism in vivo. Taken together, and in conjunction with our prior work and studies of mRNP assembly from other groups [17,42,43], we propose a model whereby Dbp2 promotes efficient assembly of mRNA-binding proteins including Yra1 onto mRNA during transcription which, in turn, prevent recycling of Dbp2 onto the properly formed mRNP (Fig. 7 and Discussion).

Figure 7. Enzymatic inhibition of Dbp2 by Yra1 restricts cycles of Dbp2-dependent mRNP remodeling in vivo.

Dbp2 is co-transcriptionally recruited to chromatin through RNA to resolve RNA duplexes. This resolution allows co-transcriptional loading of RNA-binding proteins Yra1, Mex67, and Nab2 onto the nascent RNA. After nucleotide exchange, Yra1 prevents post-transcriptional re-association by reducing the single-stranded RNA binding affinity of Dbp2. This activity likely prevents Dbp2 from accumulating on mRNA, which results in aberrant transcript stabilization and overexpression of specific gene products.

Discussion

The human genome encodes approximately 100 helicases, of which ~60% are RNA-dependent [44]. DEAD-box proteins are the largest class in the RNA helicase family and have been implicated in all aspects of RNA biology. However, there is a large gap in our knowledge regarding the precise biochemical role(s) of individual DEAD-box protein family members in the cell.

In conjunction with the current state of the mRNP assembly field [17,42,43], our collective studies provide a model for co-transcriptional assembly of mRNPs in S. cerevisiae by the DEAD-box protein Dbp2. During transcription, Dbp2 co-transcriptionally associates with actively transcribed chromatin via RNA. Based on the ATP-stimulated RNA-binding activity of Dbp2 and other DEAD-box proteins [40,41], we propose that this constitutes the ATP-bound form, which likely catalyzes structural rearrangements on the nascent RNA. Yra1, which harbors a single-stranded RNA-binding motif and exhibits single-stranded RNA-binding activity in vitro [22,45,46], would then be loaded onto newly exposed single-stranded RNA regions on the nascent RNA, along with protein-binding partners Nab2 and Mex67 [22,45,46]. Yra1 is recruited to chromatin through the interaction with the 3’ end-processing factor Pcf11 and/or the CTD of RNA Pol II [25,48], thus, this factor is already poised for “hand off” onto nascent mRNA. Although it is currently unclear if Dbp2 resolves structured RNA elements in vivo, this role is consistent with the biochemical activity in vitro and the fact that loss of DBP2 reduces the association of Yra1, Nab2 and Mex67 with poly(A)+ RNA in yeast cells [17]. Moreover, a recent study on the distribution of RNA-protein interactions and secondary structure in Arabidopsis has revealed an anti-correlative relationship [49]. With the new advances in mRNA structural analysis in living cells [2,8,32], it may be possible to determine specific RNA sequences that depend on Dbp2 or other DEAD-box proteins for resolution in vivo.

Prior studies from our laboratory showed that Yra1 interacts directly with Dbp2 and inhibits duplex unwinding activity [17]. Using smFRET, we now show that Yra1 reduces the number of dynamic molecules across a population of dsRNAs. Moreover, Yra1 does this by decreasing the RNA-binding affinity of Dbp2. DEAD-box RNA helicases exhibit structurally distinct conformations based on association with ATP and RNA [50–52]. In the absence of either, these enzymes exist in a largely open confirmation, whereas binding of ATP and RNA induces formation of a closed state with the RecA domains coming together and bending the RNA into a structure that is incompatible with an A-form helix [50,51].

A seemingly surprising finding from our study is that Dbp2 can unwind RNA hairpins in the absence of ATP. This ATP-independent activity is not due to contaminating ATP in the purification as revealed by hexokinase/glucose treatment, suggesting this is an inherent property of Dbp2. Although it is not clear how the structure of Dbp2 accommodates duplex unwinding in the absence of ATP, we note that this activity is quite low due to the low RNA-binding affinity. Moreover, it is unlikely to occur in vivo given the estimated intracellular ATP concentration of 2.6 mM in S. cerevisiae [53]. Regardless, the fact that the kinetics of unwinding are not appreciably different with or without ATP suggests that nucleotide-free Dbp2 can adopt a conformation compatible with duplex unwinding. To the best of our knowledge, our study represents the only study of DEAD-box helicase unwinding at the single molecule level with a simple, RNA hairpin substrate to date. Studies of Mss116 demonstrated an ATP-independent role in group II intron folding, a complex process that involves both unwinding and annealing [36]. Thus, it is plausible that other members of this enzyme family also exhibit ATP independent unwinding on similar simple substrates.

The enzymatic activities of many DEAD-box proteins are regulated by protein co-factors [17,54–57]. To the best of our knowledge, eIF4A and Ded1 are the only two DEAD-box proteins whose inhibition mechanisms have been determined [58–60]; Pdcd4 inhibits both the ATPase and unwinding activity of eIF4A through blocking RNA binding [58,59], whereas eIF4G inhibits the unwinding activity of Ded1 by interfering with Ded1 oligomerization and increasing RNA-binding affinity [60]. Our data demonstrates that Yra1 prevents stable association of Dbp2 with RNA, suggestive of an inhibitory mechanism similar to Pdcd4. Although the molecular basis for how this occurs is not known, the fact that Yra1 prevents accumulation of Dbp2 on mRNA transcripts indicates that this inhibition mechanism also occurs in vivo.

A major question from our study is what prevents Yra1 from inhibiting initial binding of Dbp2 to nascent RNA, prior to the mRNP assembly step. One possibility is that Yra1 and/or Dbp2 is post-translationally modified to control protein-protein interactions between these two molecules. In line with this, ubiquitination of Yra1, Nab2 and Mex67 has been shown to modulate the interactions between these three RNA-binding proteins and mRNA export factors in a manner that controls the timing of pre-mRNP assembly in the nucleus [29]. The fact that the yra1ΔC strain does not exhibit increased Dbp2 accumulation on chromatin in comparison to wild type suggests that inhibition occurs post-transcriptionally following release of the mRNA from the site of synthesis. Consistent with this, accumulation of Dbp2 causes stabilization of a subset of transcripts, a process that is predominantly post-transcriptional [61].

Given that the ADP-bound form of DEAD-box proteins has low RNA-binding affinity [40,41,62], we would predict that Dbp2 is released from mRNA after unwinding and Yra1 loading. Yra1 bound to mRNA then prevents re-association of another ATP-bound Dbp2 with the properly assembled mRNP prior to mRNA export. The latter is consistent with the fact that Yra1 prevents accumulation of Dbp2 on mRNA but also leads one to wonder why the physical interaction between Yra1 and Dbp2 is necessary. This may be answered by the fact that this complex appears to be long lived, as evidenced by the RNA-dependent co-migration of Dbp2 with Yra1 and co-purification of these two factors from yeast, suggestive of a larger role than simple sequestration of helicase activity. Future studies are necessary to determine the rate-limiting steps in mRNP assembly that would promote accumulation of a Dbp2-Yra1 complex in vivo.

Yra1 acts as an adaptor protein for recruitment of Mex67 to nascent RNA [22,47]. Nab2, a poly(A)-binding protein involved in poly(A) tail formation and mRNA export, then joins this complex as an additional adaptor protein for Mex67 [29]. Yra1 is a non-shuttling nuclear protein [45] whose release from RNA is likely mediated by ubquitination by the E3 ubiquitin ligase Tom1 [29]. Our studies suggest that Dbp2 accumulates at an intermediate step prior to Nab2 loading. Furthermore, both over-expression of DBP2 and yra1ΔC lead to mild mRNA export defects [17,22], indicating that Yra1 acts prior to mRNA transport from the nucleus. Although the identity of this step is unknown, the physical interaction between Yra1 and the nuclear exosome component Rrp6 suggests that this complex may constitute a checkpoint for mRNA quality control prior to export [63]. This would be consistent with the fact that dbp2Δ and rrp6Δ are synthetic lethal [20] and the fact that accumulation of Dbp2 causes stabilization of a subset of transcripts. The mechanism for recruitment and specificity of RNA decay factors is currently an area of intense investigation.

The mammalian ortholog of Dbp2, termed p68, is a well known oncogene whose product is involved in numerous processes requiring modulation of RNA structure, including pre-mRNA splicing [13,64,65] and rRNA processing [66]. Interestingly, the mammalian counterpart of Yra1, Aly, also interacts with p68 [67]. This suggests that the inhibition mechanism for Dbp2 may be conserved in multicellular eukaryotes. Several drugs have been successfully developed to target the DEAD-box RNA helicase eIF4A, which alter the enzymatic activity of this enzyme by manipulating RNA-binding activity and/or ATP hydrolysis activity [68–75]. Thus far, the eIF4A inhibitors Silvestrol and Paetamine A have proven useful therapeutic tools for uncontrolled cell growth [73,74], suggesting that inhibition of individual DEAD-box enzymes is a successful strategy for cancer intervention. Thus, understanding the mechanisms for enzymatic modulation of helicases in vivo is crucial for designing novel drug therapies.

Materials and Methods

For extended methods and materials, please see Supplemental Materials and Methods.

Plasmids and Yeast Strains

Please see Supplemental Table 1 and 2 for all the plasmids and yeast strains that were used in this study.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assays (ChIP)

ChIP analysis was performed as described previously [20], with the following modifications. Sheared chromatin with or without RNase treatment was used in ChIP by anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (F3165, Sigma) or anti-Rpb3 monoclonal antibody (WP012, Neoclone). Isolated DNA was then subjected to qPCR using primers listed (Supplemental Table 3). All ChIP experiments were conducted with at least three biological replicates and three technical repeats. Error bars indicate the SEM of the biological replicates.

RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP) Assays

RNA-IP was performed as described [76] with the following modifications and the isolated RNA was detected by RT-qPCR (for primers, see Supplemental Table 4). All RNA-IP experiments were performed with three biological and three technical repeats. Error bars indicate the SEM of the biological replicates.

Protein Immunoprecipitation Assays

TAP-tag immunoprecipitation was conducted as described previously [17] in the presence or absence of 70 U of RNase A and 1000 U of RNase I. For 3XFLAG-tag immunoprecipitation, cells were harvested at mid-log phase and lysed with glass beads using a mini-bead beater (BioSpec Products) in cold lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 6.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Triton X-100, 70 mM NaCl, 1X protease inhibitor (Complete, EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablet) (Roche), and 1 mM PMSF. Lysate was subjected to immunoprecipitation. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected by western blotting.

Glycerol Gradient Centrifugation

Cells were harvested at mid log phase and lysed. Lysate in the presence or absence of 70 U of RNase A and 1000 U of RNase I was subjected to 10-30% glycerol gradients in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 110 mM KOAc, 0.5% Triton X-100 and 0.1% Tween. After centrifugation in an SW41 rotor using Beckman Coulter Optima L-90K Ultracentifuge at 35,000 rpm for 18 hours at 4°C, 600μl fractions were collected from the top of the gradient and analyzed for the presence of the proteins by SDS-PAGE followed by western blotting analysis. 0.6% of the lysate was used to serve as an input (T). Molecular weights from each fraction in the glycerol gradients were determined using a standard curve that was generated by resolving the molecular weight standards comprising catalase (250 kDa), apoferritin (480 kDa), and thyroglobulin (670 kDa).

Recombinant Protein Expression and Purification

Expression and purification of pMAL MBP-TEV-DBP2 and pET21GST-YRA1C in E. coli cells was conducted as previously described [17].

Single Molecule FRET

dsRNA hairpin was purchased from Integrated DNA technologies (IDT) and labeled as described [77]. Single molecule experiments were carried out as previously described [78]. Hexokinase treatment was conducted by incubating 10 nM Dbp2 with 100 μM hexokinase and 1 mM glucose in the imaging buffer for 10 minutes before imaging.

Gel Shift Assays

10 μL reactions containing 2 mM ADP-BeFX/MgCl2, 20 U of Superase-in (Ambion), 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.01% NP-40, 2 mM DTT, 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 10 nM labeled ssRNA (16 nt, 5’-AGC ACC GUA AAG ACG C-3’), and 400 nM of recombinant, purified Dbp2 in the presence or absence of varying amounts of recombinant, purified yra1C. Varying amounts of BSA with 400 nM of recombinant, purified Dbp2 was used to serve as specificity control. Components were added in the order as indicated and incubated at 4°C for indicated time. Reaction mixtures were resolved on a non-denaturing gel and signal was detected by densitometry.

Fluorescence Anisotropy Assays

Assays were conducted in 40 μL reactions containing 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 30 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ADP-BeFx, 2 mM DTT, 40 U Superase-in (Ambion),. Time courses were performed by incubating 20 nM of Dbp2 with 10 nM of fluorescently labeled ssRNA in the presence of 2 mM ADP-BeFx and analyzing fluorescence polarization over the indicated timepoints. Varying amounts of Dbp2 and 150 nM yra1C were then incubated in the reaction buffer at 25°C for 15 min followed by addition of 10 nM fluorescently labeled ssRNA (5’-6-FAM-AGC ACC GUA AAG ACG C-3’) for an additional100 min to reach equilibrium. Fluorescence anisotropy signals of 6-FAM (λex = 495 nm and λem = 520 nm) was measured using the BioTek Synergy 4 plate reader. The data were fitted to the following equation: Y=Bmax*Xh/(Kdh+Xh) in Prism.

Transcriptional Shut Off Assays

Transcriptional shut off assays were conducted as described [79]. Cells were grown at 25°C in glucose to log phase then shift to galactose for 10 hours to induce the GAL genes expression followed by a shift to glucose to repress transcription. RNA was isolated at indicated time points, subjected to Northern Blotting analysis, and detected by densitometry. RNA half-lives were determined by measuring the amount of GAL10 or GAL7 transcript over time with respect to the stable scR1 transcript. All experiments were performed with three biological replicates.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Dbp2 associates with chromatin in an RNA-dependent manner

Loss of Yra1-Dbp2 interaction leads to over-accumulation of Dbp2 on mRNA

Yra1 inhibits duplex unwinding by reducing RNA-binding activity of Dbp2

Yra1-dependent inhibition of Dbp2 prevents aberrant mRNA stabilization

Regulation of Dbp2 is critical for maintaining proper gene expression

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Tran laboratory for thoughtful discussions. This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM097332 to E.J.T., P30CA023168 for core facilities at the Purdue University Center for Cancer Research, the Clinical Sciences Center of the Medical Research Council (RCUK MC-A658-5TY10) and a startup grant from the Imperial College London to D.R. We also thank Xin Liu from Carol Fierke's laboratory (University of Michigan) for technical assistance with fluorescence anisotropy assays and Susan Baserga (Yale University) and members of her laboratory for discussion and technical assistance with gradient fractionation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zorio DA, Bentley DL. The link between mRNA processing and transcription: communication works both ways. Exp Cell Res. 2004;296:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.03.019. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.03.019S0014482704001326 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rouskin S, Zubradt M, Washietl S, Kellis M, Weissman JS. Genome-wide probing of RNA structure reveals active unfolding of mRNA structures in vivo. Nature. 2014;505:701–705. doi: 10.1038/nature12894. doi:nature12894 [pii] 10.1038/nature12894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cramer P, Srebrow A, Kadener S, Werbajh S, de la Mata M, Melen G, et al. Coordination between transcription and pre-mRNA processing. FEBS Lett. 2001;498:179–182. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02485-1. doi:S0014-5793(01)02485-1 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen CYA, Bin Shyu A. Emerging mechanisms of mRNP remodeling regulation, Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2014;5:713–22. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1241. doi:10.1002/wrna.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laurent FX, Sureau A, Klein AF, Trouslard F, Gasnier E, Furling D, et al. New function for the RNA helicase p68/DDX5 as a modifier of MBNL1 activity on expanded CUG repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:3159–3171. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1228. doi:gkr1228 [pii]10.1093/nar/gkr1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herschlag D. RNA chaperones and the RNA folding problem. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20871–20874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.20871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan C, Russell R. Roles of DEAD-box proteins in RNA and RNP Folding. RNA Biol. 2010;7:667–676. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.6.13571. doi:13571 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wan Y, Qu K, Zhang QC, a Flynn R, Manor O, Ouyang Z, et al. Landscape and variation of RNA secondary structure across the human transcriptome. Nature. 2014;505:706–9. doi: 10.1038/nature12946. doi:10.1038/nature12946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.V Ramos SB, Laederach A. Molecular biology: A second layer of information in {RNA} Nature. 2014;505:621–622. doi: 10.1038/505621a. doi:10.1038/505621a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarmoskaite I, Russell R. RNA helicase proteins as chaperones and remodelers. Annu Rev Biochem. 2014;83:697–725. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035546. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Putnam AA, Jankowsky E. DEAD-box helicases as integrators of RNA, nucleotide and protein binding. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829:884–893. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.02.002. doi:S1874-9399(13)00024-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linder P, Fuller-Pace FV. Looking back on the birth of DEAD-box RNA helicases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gene Regul. Mech. 2013;1829:750–755. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.03.007. doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kar A, Fushimi K, Zhou X, Ray P, Shi C, Chen X, et al. RNA helicase p68 (DDX5) regulates tau exon 10 splicing by modulating a stem-loop structure at the 5’ splice site. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1812–1821. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01149-10. doi:MCB.01149-10 [pii]10.1128/MCB.01149-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, et al. Association of missense and 5’-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature. 1998;393:702–705. doi: 10.1038/31508. doi:10.1038/31508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasegawa M, Smith MJ, Iijima M, Tabira T, Goedert M. FTDP-17 mutations N279K and S305N in tau produce increased splicing of exon 10. FEBS Lett. 1999;443:93–96. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01696-2. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(98)01696-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Q, Jankowsky E. ATP- and ADP-dependent modulation of RNA unwinding and strand annealing activities by the DEAD-box protein DED1. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13591–13601. doi: 10.1021/bi0508946. doi:10.1021/bi0508946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma WK, Cloutier SC, Tran EJ. The DEAD-box protein Dbp2 functions with the RNA-binding protein Yra1 to promote mRNP assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 2013;425:3824–3838. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tran EJ, Zhou Y, Corbett AH, Wente SR. The DEAD-box protein Dbp5 controls mRNA export by triggering specific RNA:protein remodeling events. Mol Cell. 2007;28:850–859. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.019. doi:S1097-2765(07)00631-4 [pii]10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barta I, Iggo R. Autoregulation of expression of the yeast Dbp2p “DEAD-box” protein is mediated by sequences in the conserved DBP2 intron. EMBO J. 1995;14:3800–3808. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cloutier SC, Ma WK, Nguyen LT, Tran EJ. The DEAD-box RNA helicase Dbp2 connects RNA quality control with repression of aberrant transcription. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:26155–26166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.383075. doi:M112.383075 [pii] 10.1074/jbc.M112.383075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson SA, Kim H, Erickson B, Bentley DL. The export factor Yra1 modulates mRNA 3’ end processing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1164–1171. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2126. doi:nsmb.2126 [pii]10.1038/nsmb.2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zenklusen D, Vinciguerra P, Strahm Y, Stutz F. The yeast hnRNP-Like proteins Yra1p and Yra2p participate in mRNA export through interaction with Mex67p. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4219–4232. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4219-4232.2001. doi:10.1128/MCB.21.13.4219-4232.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck ZT, Cloutier SC, Schipma MJ, Petell CJ, Ma WK, Tran EJ. Regulation of Glucose-Dependent Gene Expression by the RNA Helicase Dbp2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2014;198:1001–14. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.170019. doi:genetics.114.170019 [pii] 10.1534/genetics.114.170019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abruzzi KC, Lacadie S, Rosbash M. Biochemical analysis of TREX complex recruitment to intronless and intron-containing yeast genes. EMBO J. 2004;23:2620–2631. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600261. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.76002617600261 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson SA, Cubberley G, Bentley DL. Cotranscriptional recruitment of the mRNA export factor Yra1 by direct interaction with the 3’ end processing factor Pcf11. Mol Cell. 2009;33:215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.007. doi:S1097-2765(08)00848-4 [pii]10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krebber H, Taura T, Lee MS, Silver PA. Uncoupling of the hnRNP Npl3p from mRNAs during the stress-induced block in mRNA export. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1994–2004. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorsch LC, Dockendorff TC, Cole CN. A conditional allele of the novel repeat-containing yeast nucleoporin RAT7/NUP159 causes both rapid cessation of mRNA export and reversible clustering of nuclear pore complexes. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:939–955. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.4.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Del Priore V, Snay CA, Bahr A, Cole CN. The product of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RSS1 gene, identified as a high-copy suppressor of the rat7-1 temperature-sensitive allele of the RAT7/NUP159 nucleoporin, is required for efficient mRNA export. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1601–1621. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.10.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iglesias N, Tutucci E, Gwizdek C, Vinciguerra P, Von Dach E, Corbett AH, et al. Ubiquitin-mediated mRNP dynamics and surveillance prior to budding yeast mRNA export. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1927–1938. doi: 10.1101/gad.583310. doi:24/17/1927 [pii] 10.1101/gad.583310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puig O, Caspary F, Rigaut G, Rutz B, Bouveret E, Bragado-Nilsson E, et al. The tandem affinity purification (TAP) method: a general procedure of protein complex purification. Methods. 2001;24:218–229. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1183. doi:10.1006/meth.2001.1183S1046-2023(01)91183-1 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Svoboda P, Di Cara a. Hairpin RNA: a secondary structure of primary importance. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006;63:901–8. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5558-5. doi:10.1007/s00018-005-5558-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding Y, Tang Y, Kwok CK, Zhang Y, Bevilacqua PC, Assmann SM. In vivo genome-wide profiling of RNA secondary structure reveals novel regulatory features. Nature. 2014;505:696–700. doi: 10.1038/nature12756. doi:10.1038/nature12756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samatanga B, Klostermeier D. DEAD-box RNA helicase domains exhibit a continuum between complete functional independence and high thermodynamic coupling in nucleotide and RNA duplex recognition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:1–11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku747. doi:10.1093/nar/gku747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banroques J, Cordin O, Doere M, Linder P, Tanner NK. A conserved phenylalanine of motif IV in superfamily 2 helicases is required for cooperative, ATP-dependent binding of RNA substrates in DEAD-box proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3359–3371. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01555-07. doi:MCB.01555-07 [pii]10.1128/MCB.01555-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theissen B, Karow AR, Köhler J, Gubaev A, Klostermeier D. Cooperative binding of ATP and RNA induces a closed conformation in a DEAD box RNA helicase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:548–553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705488105. doi:10.1073/pnas.0705488105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karunatilaka KS, Solem A, Pyle AM, Rueda D. Single-molecule analysis of Mss116-mediated group II intron folding. Nature. 2010;467:935–939. doi: 10.1038/nature09422. doi:nature09422 [pii]10.1038/nature09422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chong YT, Koh JLY, Friesen H, Duffy K, Cox MJ, Moses A, et al. Yeast Proteome Dynamics from Single Cell Imaging and Automated Analysis. Cell. 2015;161:1413–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.051. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rudolph MG, Klostermeier D. When core competence is not enough: functional interplay of the DEAD-box helicase core with ancillary domains and auxiliary factors in RNA binding and unwinding. Biol. Chem. 2015;396:849–65. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2014-0277. doi:10.1515/hsz-2014-0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu F, Putnam AA, Jankowsky E. DEAD-box helicases form nucleotide-dependent, long-lived complexes with RNA. Biochemistry. 2014;53:423–433. doi: 10.1021/bi401540q. doi:10.1021/bi401540q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao W, Coman MM, Ding S, Henn A, Middleton ER, Bradley MJ, et al. Mechanism of Mss116 ATPase reveals functional diversity of DEAD-Box proteins. J Mol Biol. 2011;409:399–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.004. doi:S0022-2836(11)00383-4 [pii]10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henn A, Cao W, Hackney DD, De La Cruz EM. The ATPase cycle mechanism of the DEAD-box rRNA helicase. DbpA, J Mol Biol. 2008;377:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.046. doi:S0022-2836(07)01675-0 [pii]10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oeffinger M, Montpetit B. Emerging properties of nuclear RNP biogenesis and export. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015;34:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.04.007. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Babour A, Dargemont C, Stutz F. Ubiquitin and assembly of export competent mRNP. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1819:521–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.12.006. doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Umate P, Tuteja N, Tuteja R. Genome-wide comprehensive analysis of human helicases. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2011;4:1–20. doi: 10.4161/cib.4.1.13844. doi:10.4161/cib.4.1.13844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stutz F, Bachi A, Doerks T, Braun IC, Seraphin B, Wilm M, et al. REF, an evolutionary conserved family of hnRNP-like proteins, interacts with TAP/Mex67p and participates in mRNA nuclear export. RNA. 2000;6:638–650. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maris C, Dominguez C, Allain FHT. The RNA recognition motif, a plastic RNA-binding platform to regulate post-transcriptional gene expression. FEBS J. 2005;272:2118–2131. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04653.x. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strässer K, Hurt E. Splicing factor Sub2p is required for nuclear mRNA export through its interaction with Yra1p. Nature. 2001;413:648–652. doi: 10.1038/35098113. doi:10.1038/35098113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MacKellar AL, Greenleaf AL. Cotranscriptional association of mRNA export factor Yra1 with C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:36385–36395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.268144. doi:M111.268144 [pii]10.1074/jbc.M111.268144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gosai SJ, Foley SW, Wang D, Silverman IM, Selamoglu N, Nelson ADL, et al. Global analysis of the RNA-protein interaction and RNA secondary structure landscapes of the Arabidopsis nucleus. Mol. Cell. 2015;57:376–88. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.004. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sengoku T, Nureki O, Nakamura A, Kobayashi S, Yokoyama S. Structural Basis for RNA Unwinding by the DEAD-Box Protein Drosophila Vasa. Cell. 2006;125:287–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.054. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andersen CB, Ballut L, Johansen JS, Chamieh H, Nielsen KH, Oliveira CL, et al. Structure of the exon junction core complex with a trapped DEAD-box ATPase bound to RNA. Science (80−. ) 2006;313:1968–1972. doi: 10.1126/science.1131981. doi:1131981 [pii]10.1126/science.1131981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aregger R, Klostermeier D. The DEAD box helicase YxiN maintains a closed conformation during ATP hydrolysis. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10679–10681. doi: 10.1021/bi901278p. doi:10.1021/bi901278p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ozalp VC, Pedersen TR, Nielsen LJ, Olsen LF. Time-resolved measurements of intracellular ATP in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae using a new type of nanobiosensor. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:37579–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.155119. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.155119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hilbert M, Kebbel F, Gubaev A, Klostermeier D. eIF4G stimulates the activity of the DEAD box protein eIF4A by a conformational guidance mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:2260–2270. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1127. doi:gkq1127 [pii]10.1093/nar/gkq1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schutz P, Bumann M, Oberholzer AE, Bieniossek C, Trachsel H, Altmann M, et al. Crystal structure of the yeast eIF4A-eIF4G complex: an RNA-helicase controlled by protein-protein interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9564–9569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800418105. doi:0800418105 [pii]10.1073/pnas.0800418105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Granneman S, Lin C, Champion EA, Nandineni MR, Zorca C, Baserga SJ. The nucleolar protein Esf2 interacts directly with the DExD/H box RNA helicase, Dbp8, to stimulate ATP hydrolysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3189–3199. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl419. doi:34/10/3189 [pii]10.1093/nar/gkl419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alcazar-Roman AR, Tran EJ, Guo S, Wente SR. Inositol hexakisphosphate and Gle1 activate the DEAD-box protein Dbp5 for nuclear mRNA export. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:711–716. doi: 10.1038/ncb1427. doi:ncb1427 [pii]10.1038/ncb1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang JH, Cho YH, Sohn SY, Choi JM, Kim A, Kim YC, et al. Crystal structure of the eIF4A-PDCD4 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3148–3153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808275106. doi:0808275106 [pii]10.1073/pnas.0808275106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loh PG, Yang HS, Walsh MA, Wang Q, Wang X, Cheng Z, et al. Structural basis for translational inhibition by the tumour suppressor Pdcd4. EMBO J. 2009;28:274–285. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.278. doi:emboj2008278 [pii]10.1038/emboj.2008.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Putnam AA, Gao Z, Liu F, Jia H, Yang Q, Jankowsky E. Division of Labor in an Oligomer of the DEAD-Box RNA Helicase Ded1p. Mol. Cell. 2015;59:541–52. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.030. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bevilacqua A, Ceriani MC, Capaccioli S, Nicolin A. Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression by degradation of messenger RNAs. J. Cell. Physiol. 2003;195:356–372. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10272. doi:10.1002/jcp.10272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Henn A, Cao W, Licciardello N, Heitkamp SE, Hackney DD, De La Cruz EM. Pathway of ATP utilization and duplex rRNA unwinding by the DEAD-box helicase, DbpA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:4046–4050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913081107. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913081107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zenklusen D, Vinciguerra P, Wyss J-C, Stutz F. Stable mRNP formation and export require cotranscriptional recruitment of the mRNA export factors Yra1p and Sub2p by Hpr1p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:8241–53. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.23.8241-8253.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu ZR. p68 RNA helicase is an essential human splicing factor that acts at the U1 snRNA-5’ splice site duplex. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5443–5450. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.15.5443-5450.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guil S, Gattoni R, Carrascal M, Abian J, Stevenin J, Bach-Elias M. Roles of hnRNP A1, SR proteins, and p68 helicase in c-H-ras alternative splicing regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2927–2941. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.8.2927-2941.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jalal C, Uhlmann-Schiffler H, Stahl H. Redundant role of DEAD box proteins p68 (Ddx5) and p72/p82 (Ddx17) in ribosome biogenesis and cell proliferation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3590–3601. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm058. doi:gkm058 [pii]10.1093/nar/gkm058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zonta E, Bittencourt D, Samaan S, Germann S, Dutertre M, Auboeuf D. The RNA helicase DDX5/p68 is a key factor promoting c-fos expression at different levels from transcription to mRNA export. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:554–564. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1046. doi:gks1046 [pii] 10.1093/nar/gks1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eberle J, Krasagakis K, Orfanos CE. Translation initiation factor eIF-4A1 mRNA is consistently overexpressed in human melanoma cells in vitro. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:396–401. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970502)71:3<396::aid-ijc16>3.0.co;2-e. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970502)71:3<396::AID IJC16>3.0.CO;2-E [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shuda M, Kondoh N, Tanaka K, Ryo A, Wakatsuki T, Hada A, et al. Enhanced expression of translation factor mRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:2489–2494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gao F, Zhang P, Zhou C, Li J, Wang Q, Zhu F, et al. Frequent loss of PDCD4 expression in human glioma: possible role in the tumorigenesis of glioma. Oncol Rep. 2007;17:123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wen YH, Shi X, Chiriboga L, Matsahashi S, Yee H, Afonja O. Alterations in the expression of PDCD4 in ductal carcinoma of the breast. Oncol Rep. 2007;18:1387–1393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bordeleau ME, Cencic R, Lindqvist L, Oberer M, Northcote P, Wagner G, et al. RNA-mediated sequestration of the RNA helicase eIF4A by Pateamine A inhibits translation initiation. Chem Biol. 2006;13:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.10.005. doi:S1074-5521(06)00384-X [pii]10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bordeleau ME, Robert F, Gerard B, Lindqvist L, Chen SM, Wendel HG, et al. Therapeutic suppression of translation initiation modulates chemosensitivity in a mouse lymphoma model. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2651–2660. doi: 10.1172/JCI34753. doi:10.1172/JCI34753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bordeleau ME, Matthews J, Wojnar JM, Lindqvist L, Novac O, Jankowsky E, et al. Stimulation of mammalian translation initiation factor eIF4A activity by a small molecule inhibitor of eukaryotic translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10460–10465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504249102. doi:0504249102 [pii]10.1073/pnas.0504249102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Low WK, Dang Y, Schneider-Poetsch T, Shi Z, Choi NS, Merrick WC, et al. Inhibition of eukaryotic translation initiation by the marine natural product pateamine A. Mol Cell. 2005;20:709–722. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.008. doi:S1097-2765(05)01678-3 [pii]10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gilbert C, Svejstrup JQ. RNA immunoprecipitation for determining RNA-protein associations in vivo. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2704s75. Chapter 27. Unit 27 4. doi:10.1002/0471142727.mb2704s75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wood S, Ferré-D'Amaré AR, Rueda D. Allosteric tertiary interactions preorganize the c-di-GMP riboswitch and accelerate ligand binding. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012;7:920–927. doi: 10.1021/cb300014u. doi:10.1021/cb300014u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mundigala H, Michaux JB, Feig AL, Ennifar E, Rueda D. HIV-1 DIS stem loop forms an obligatory bent kissing intermediate in the dimerization pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:7281–7289. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku332. doi:10.1093/nar/gku332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Coller J. Chapter 14 Methods to Determine mRNA Half-Life in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 2008;448:267–284. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02614-1. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02614-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Strasser K, Hurt E. Yra1p, a conserved nuclear RNA-binding protein, interacts directly with Mex67p and is required for mRNA export. EMBO J. 2000;19:410–420. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.3.410. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.3.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brykailo MA, McLane LM, Fridovich-Keil J, Corbett AH. Analysis of a predicted nuclear localization signal: implications for the intracellular localization and function of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNA-binding protein Scp160. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:6862–6869. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm776. doi:gkm776 [pii]10.1093/nar/gkm776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lamichhane R, Solem A, Black W, Rueda D. Single-molecule FRET of protein-nucleic acid and protein-protein complexes: Surface passivation and immobilization. Methods. 2010;52:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.06.010. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.