Summary

The motor neuron progenitor domain in the ventral spinal cord gives rise to multiple subtypes of motor neurons and glial cells. Here we examined whether progenitors found in this domain are multipotent and what signals contribute to their cell type-specific differentiation. Using an in vitro neural differentiation model, we demonstrate that motor neuron progenitor differentiation is iteratively controlled by Notch signaling. First, Notch controls the timing of motor neuron genesis by repressing Neurogenin 2 (Ngn2) and maintaining Olig2-positive progenitors in a proliferative state. Second, in an Ngn2-independent manner, Notch contributes to the specification of median vs. hypaxial motor column identity and lateral vs. medial divisional identity of limb innervating motor neurons. Thus, motor neuron progenitors are multipotent and their diversification is controlled by Notch signaling that iteratively increases cellular diversity arising from a single neural progenitor domain.

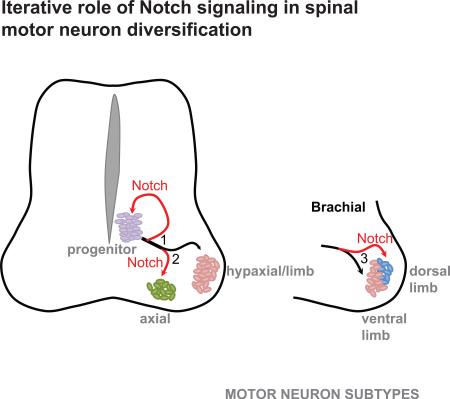

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Establishment of neuronal diversity relies on two principal mechanisms – spatial patterning of neuroepithelium into discrete progenitor domains (Briscoe and Ericson, 2001; Dessaud et al., 2008; Sussel et al., 1999) and intradomain diversification of differentiating progenitors into multiple neuronal and glial subtypes. During early stages of neural tube patterning, diffusible signals establish eleven principal dorso-ventral progenitor domains in the developing spinal cord (Garcia-Campmany et al., 2010). Neural progenitors within the motor neuron progenitor (pMN) domain, marked by expression of Olig2, first generate multiple subtypes of spinal motor neurons, followed by production of oligodendrocytes and astrocytes (Masahira et al., 2006; Novitch et al., 2001; Zhou and Anderson, 2002; Zhou et al., 2001).

While specification of the pMN domain by spatially- and temporally-graded sonic hedgehog and retinoid signals has been extensively studied (Briscoe et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2011; Ericson et al., 1997; Novitch et al., 2003), mechanisms contributing to the diversification of pMN progenitors into different neuronal and glial subtypes are less understood. Heterochronic transplantation studies established that late Olig2+ progenitors have a limited developmental potential and are unable to generate motor neurons, even when grafted into earlier neurogenic neural tube (Mukouyama et al., 2006). Whether early specified Olig2+ progenitors consist of a mixture of lineage committed progenitors or whether each cell is multipotent remains to be determined.

The Notch signaling pathway contributes to neural diversification in invertebrates and vertebrates through two principal mechanisms (Moohr, 1919; Udolph, 2012) - specification of cell fate indirectly through the regulation of the timing of neurogenesis and by direct Notch mediated regulation of cell fate determinants in asymmetrically dividing cells. In laminar regions of the vertebrate CNS, inhibition of Notch signaling typically results in premature neurogenesis and increased production of early born neuronal subtypes at the expense of later born cells (Livesey and Cepko, 2001; Nelson et al., 2007). A more direct role of Notch signaling has been demonstrated for several cell types in the CNS, including in the developing retina where activation of Notch in postmitotic retinal cells induces Muller glia identity and represses rod photoreceptor cell fate (Mizeracka et al., 2013) and in the developing ventral spinal cord, where Notch has been shown to specify V2b over V2a interneuron identity (Marklund et al., 2010; Peng et al., 2007; Ramos et al., 2010; Rocha et al., 2009).

Within the motor neuron progenitor domain, it has been proposed that Notch controls motor neuron subtype identity primarily indirectly by controlling the timing of neurogenesis and gliogenesis. Gde2-null mice exhibit increased Notch signaling in late pMN progenitors, accompanied by a decrease in neurogenic divisions and a reduction in the number of presumably late born hypaxial motor column (HMC) or lateral motor column (LMC) motor neurons. Machado et al. observed that a reduction in Notch signaling promotes specification of phrenic motor neurons, a subpopulation of HMCs (Machado et al., 2014), but the precise mechanisms of Notch involvement have not been examined. The Notch ligand Jag2 has been shown to prevent both motor neuron and oligodendroglial differentiation by locking developing chick spinal cord cells in a progenitor identity (Rabadan et al., 2012). Consistent with these observations, pharmacological inhibition of Notch signaling promotes differentiation of human pMNs into motor neurons (Ben-Shushan et al., 2015). However, the effect of this treatment on subtype identity of the resulting neurons has not been examined.

Interpretation of the effects of Notch manipulation in vivo are complicated by the complexity of neural tissue and poor temporal resolution of motor neuron subtype differentiation. To assess the role of Notch signaling in motor neuron subtype specification, we took advantage of a controlled, pharmacologically and genetically-accessible embryonic stem cell (ESC) differentiation model (Wichterle et al., 2002). In vitro-derived motor neurons acquire segmentally-appropriate columnar, divisional and pool subtype identities; migrate to proper locations within the spinal cord; and project axons toward appropriate muscle targets upon transplantation into the developing neural tube (Peljto et al., 2010). Taking advantage of this bone fide model of motor neuron development, we demonstrate that multipotent motor neuron progenitors iteratively utilize the Notch signaling pathway to control the timing of motor neuron genesis and motor neuron subtype identity.

Results

Temporal sequence of motor neuron genesis and gliogenesis during ESC differentiation

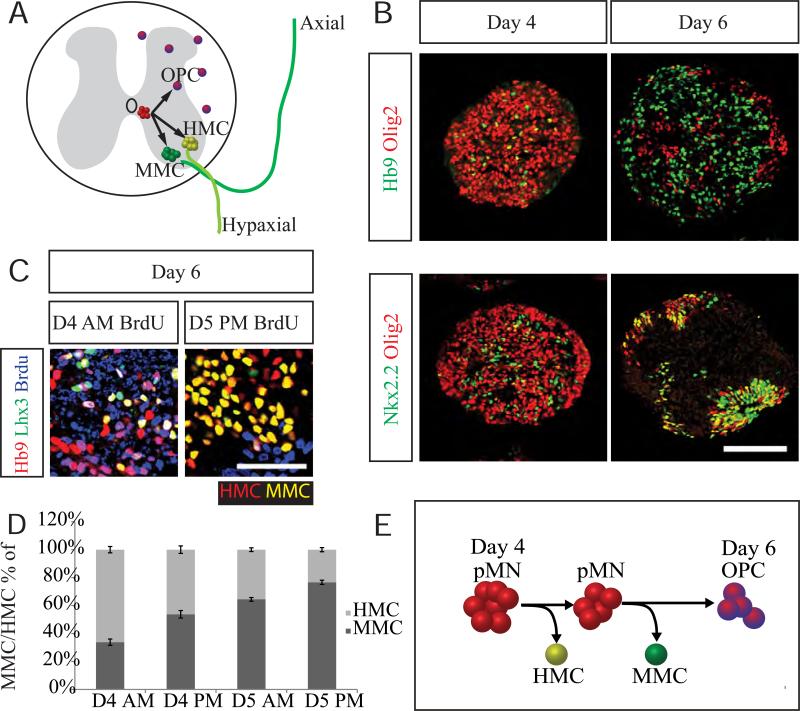

ESCs differentiated into cervical spinal motor neuron identity in the presence of retinoic acid (RA) and Smoothened agonist (SAG) acquire appropriate median motor column (MMC) and HMC identity (Figure 1A) (Peljto et al., 2010; Wichterle et al., 2002). At day four of mouse ESC differentiation, the majority of cells are patterned into Olig2+ motor neuron progenitors lacking the expression of oligodendroglial progenitor marker Nkx2.2 (Figure 1B) (Zhou et al., 2001). By day 6, a majority of Olig2+ cells differentiated into Hb9+ postmitotic motor neurons. Many of the remaining Olig2+ cells co-express Nkx2.2, indicating a switch to oligodendrocyte precursor (OPC) identity (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Temporal progression of pMN differentiation.

A. In cervical spinal cord, early pMNs differentiate into MMC and HMC motor neurons that migrate to their appropriate positions in the ventral horn and project their axons axially or hypaxially, respectively. After motor neurons are generated Olig2+ progenitors in the pMN domain acquire expression of Nkx2.2 and differentiate into oligodendrocytes precursors that migrate throughout the spinal cord. B. ESC to motor neuron differentiation recapitulates the neuronal to glial cell fate switch. In early day 4 cultures, Olig2+ progenitors do not express Nkx2.2 and many differentiate into Hb9+ motor neurons on day 5-6 of differentiation. Many Olig2+ cells present on day 6 of differentiation acquire expression of Nkx2.2. Scale bar marks 100μm. C. BrdU birthdating study reveals that early pMNs preferentially differentiate into HMC motor neurons while later pMNs preferentially differentiate into MMC motor neurons (cells were examined on day 6, BrdU was applied between day 4 and 5 as indicated). Scale bar marks 50μm. D. Quantification of Lhx3+ (MMC) and Lhx3− (HMC) motor neurons born prior to the application of BrdU (BrdU−). Data reported as mean ± SEM (n=3 independent differentiations).

Motor neurons become postmitotic over a relatively short period spanning from day 4 to day 5 of differentiation. To determine whether early born motor neurons acquire different subtype identity compared to late born motor neurons, we combined bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) birthdating with immunostaining for Hb9 (expressed by both MMC and HMC motor neurons), and Lhx3 to distinguish between MMC (Lhx3+) and HMC (Lhx3−) motor neurons. We demonstrate that 66% of motor neurons born on or before day 4 are Lhx3− HMC motor neurons (Figure 1C-D). This contrasts with the presence of ~75% of Lhx3+ MMC motor neurons at the end of differentiation, indicating that early pMNs preferentially give rise to HMC motor neurons and later differentiating progenitors give rise primarily to MMC motor neurons (Fig 1E).

Notch signaling controls the timing of motor neuron differentiation

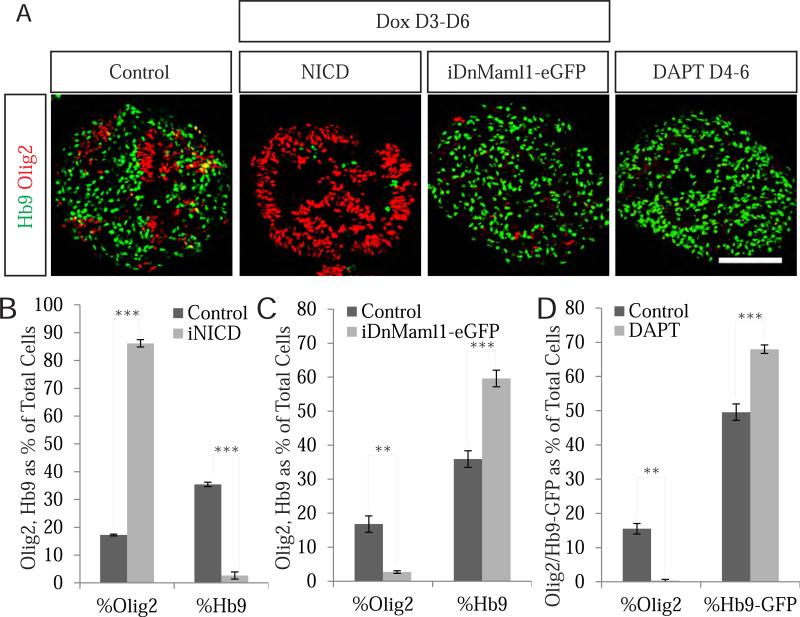

To test whether regulation of Notch signaling controls timing of motor neuron differentiation, we generated an inducible ESC line carrying a V5-tagged Notch intracellular domain (NICD) under the control of a doxycycline-inducible promoter. NICD, a product of γ-secretase cleavage of the Notch receptor, transduces the Notch signal to the nucleus where it interacts with RBP-J and Mastermind1 (Maml1) co-activators to regulate Notch target genes (Hori et al., 2013). Treatment of embryoid bodies with doxycycline on day 3 of differentiation resulted in robust expression of NICD-V5 and activation of Notch signaling in day 4 embryoid bodies (Figure S1A, C). Notch activation interfered with motor neuron differentiation as Hb9+ cells decreased from 35% to less than 3% (the remaining few Hb9 cells escaped NICD induction) and the percentage of Olig2+ cells increased from 17% to over 86% of all cells (Figure 2A-B). Thus, cell autonomous Notch activation prevents motor neuron differentiation and increases the number of Olig2+ progenitors.

Figure 2. Notch signaling controls the timing of motor neuron differentiation.

A. NICD induction strongly inhibits motor neuron differentiation and maintains Olig2+ pMNs. Conversely, inhibition of Notch signaling by overexpression of DnMaml1-eGFP or treatment with DAPT induces motor neuron differentiation. Scale bar marks 100μm. B. Quantification of Hb9 (P<.001) and Olig2 (P<.001) expressing cells as a percentage of total cells in day 6 control and NICD-induced EBs. Data reported as mean ± SEM (n=3). C. Quantification of Olig2+ (P<.001) and Hb9-GFP+ (P<.001) cells in control versus DAPT treated cultures. Data reported as mean ± SEM (n=3). D. Quantification of Olig2+ (P=.006) and Hb9+ (P<.001) cells in day 6 control versus DnMaml1-eGFP EBs. Data reported as mean ± SEM (n=3). See also Figure S1.

To determine whether Notch inactivation is sufficient to initiate motor neuron genesis we generated an inducible ESC line expressing a dominant negative form of the Notch co-factor Maml1 fused to eGFP (DnMaml1-eGFP) under the control of a doxycycline-inducible promoter (Maillard et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2000) (Figure S2B). Induction of DnMaml1-eGFP led to efficient inactivation of Notch signaling in pMNs (Figure S2C) and to a significant increase in Hb9+ motor neurons from 36% to 60% of all cells (Figure 2A,C), with a corresponding reduction in Olig2+ cells from 17% to less than 3% of cells on day 6 of differentiation (Figure 2 A,C). Pharmacological inhibition of γ-secretase by DAPT treatment on day 4 had an even stronger neurogenic effect, depleting pMNs to less than 1% and increasing motor neurons to 68% as revealed by flow cytometric quantification of HB9-GFP+ cells (Figure 2 A,D). Birthdating analysis revealed that DAPT treatment also accelerated motor neuron generation, increasing the number of motor neurons that became postmitotic on day 4 from 41% to 78% (Figure S2A-B). Together these findings indicate that early pMNs are multipotent progenitors, whose fate is controlled by Notch signaling. Inhibition of Notch results in uniform and accelerated differentiation of progenitors into postmitotic neurons, while activation of Notch results in the maintenance of Olig2 progenitor identity.

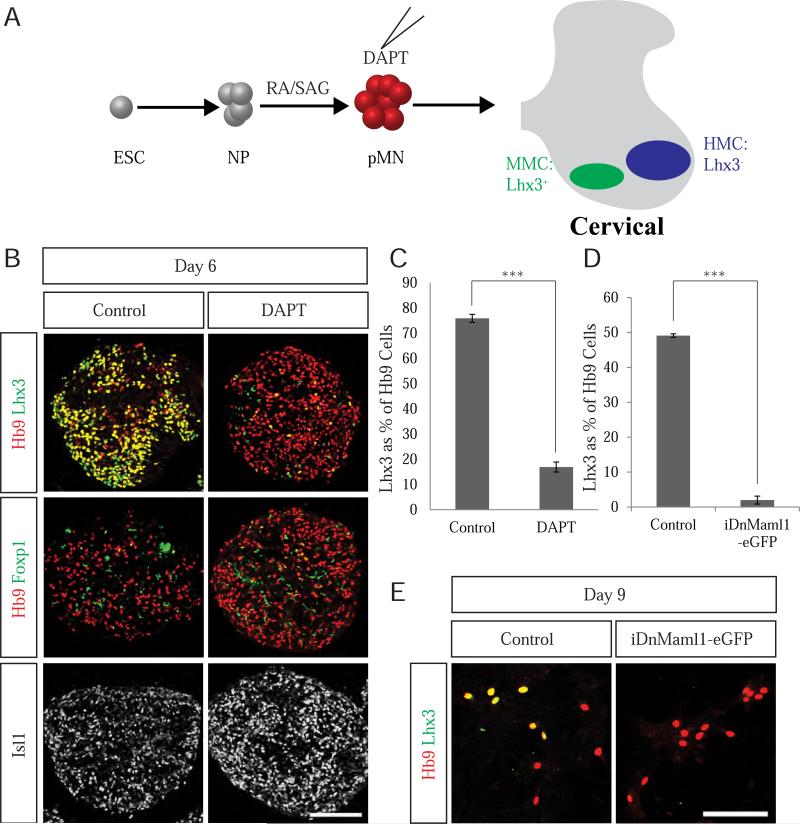

Notch inactivation respecifies MMC neurons into segmentally-appropriate columnar subtypes

Treatment of pMNs early on day 4 with DAPT revealed a dramatic shift in motor neuron columnar identity from predominantly Lhx3+ MMC motor neurons to predominantly Lhx3−, Foxp1− HMC motor neurons (Figure 3B-C). DAPT treatment does not simply repress expression of Lhx3, as we detect robust Lhx3 expression in DAPT treated motor neurons on day 5 of differentiation (Figure S3A). This is consistent with transient expression of Lhx3 in all nascent motor neurons before its selective downregulation in HMC and LMC cells. Caspase-3 staining was not elevated in day 5 DAPT-treated motor neurons ruling out the possibility that the shift in motor neuron identity is due to selective death of MMC motor neurons (Figure S3A, B). Importantly, DnMaml1-eGFP induction phenocopied the decrease in Lhx3 expression from 49% to just 2% of Hb9+ cells (Figure 3D-E), indicating that Notch activity is required for maintained expression of Lhx3 and its inactivation leads to a near-complete conversion of motor neuron columnar subtype identity from MMC to HMC.

Figure 3. Notch inactivation increases generation of HMC motor neurons at the expense of MMC motor neurons.

A. The use of RA in ESC to motor neuron differentiation results in cervical cultures where motor neurons are organized into the Lhx3+ MMC and Lhx3− HMC columns. B. Control conditions yield motor neurons that are primarily Lhx3+ MMC motor neurons. DAPT treatment of motor neuron progenitors led to dramatic downregulation in Lhx3 expression. Consistent with a conversion from MMC to HMC identity, Foxp1 was not expressed in both control and DAPT treated conditions and DAPT treatment led to increased Isl1 immunoreactivity. Scale bar marks 100μm. C. Quantification of Lhx3 expression in day 6 control and DAPT-treated motor neurons (P<0.001). Data reported as mean ± SEM (n=3). D. Quantification of Lhx3 expression in dissociated day 9 motor neurons after DnMaml1-eGFP overexpression. Data reported as mean ± SEM (n=3). E. DnMaml1-eGFP induction also increases the percentage of HMC motor neurons at the expense of MMC motor neurons in dissociated day 9 cultures. Scale bar marks 100μm. See also Figure S3.

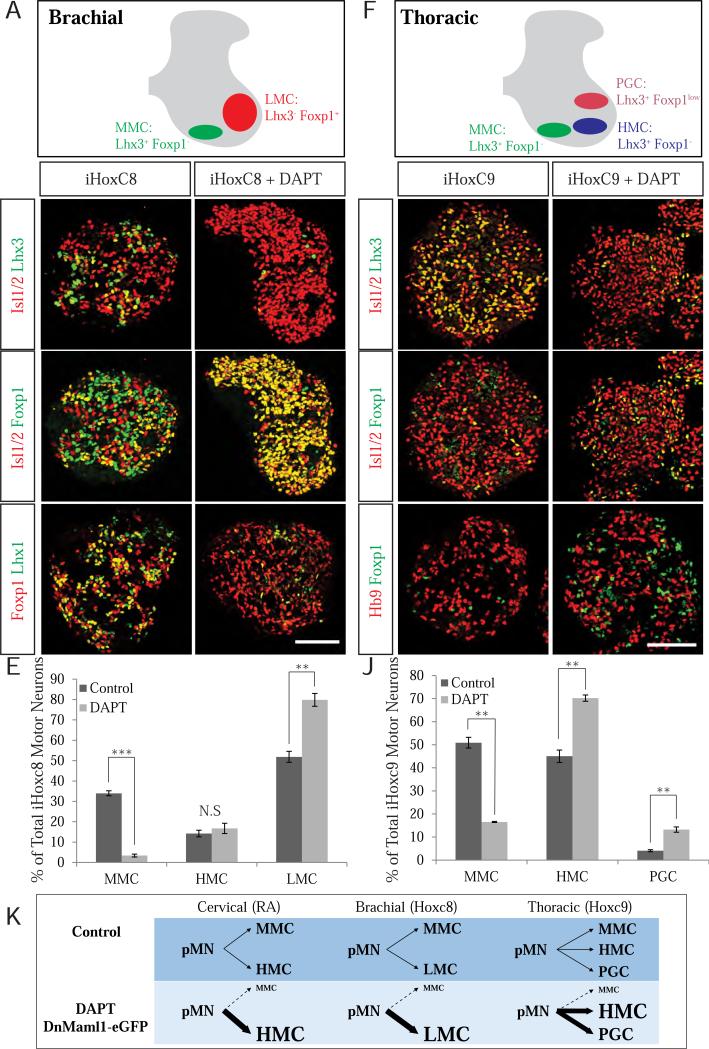

While the MMC spans the entire rostro-caudal axis of the spinal cord, the HMC motor column is limited to the neck and trunk spinal regions. At limb levels, HMC neurons are largely replaced by the Foxp1-expressing lateral motor column (LMC) motor neurons that project their axons to the limbs (Figure 6A). To examine the effects of Notch inhibition on motor neuron columnar identity at limb (brachial) and thoracic spinal levels, we took advantage of observations that misexpression of Hoxc8 and Hoxc9 transcription factors is sufficient to induce ectopic brachial and thoracic motor neurons, respectively (Dasen et al., 2008; Dasen et al., 2003; Jung et al., 2010).

We generated an inducible Hoxc8 ESC line and demonstrated that doxycycline treatment of EBs on day 3 of differentiation resulted in a specification of a significant number of limb innervating Foxp1+ LMC motor neurons (~52%), with a smaller number of Lhx3+ MMC neurons (34%) and a minority of HMC neurons (~14%) (Figure 4B-C, and E). Similar to cervical cultures, DAPT treatment on day 4 led to a dramatic decrease in Lhx3-expressing MMC motor neurons from 34% to just 3% of Isl1/2+ motor neurons (Figure 4B’, E). In contrast to cervical cultures, the number of HMC motor neurons was increased only minimally (Figure 4E), while Foxp1-expressing LMC motor neurons increased dramatically from 52% to 80% (Figure 4C’, E). LMC neurons in DAPT-treated cultures exhibited very strong Isl1 immunoreactivity indicating that they differentiated primarily into medial LMC (LMCm) neurons innervating ventral limb muscles (Sockanathan and Jessell, 1998; Tsuchida et al., 1994). Accordingly, expression of LMCl markers Lhx1 and Hb9 (Kania et al., 2000) was nearly completely extinguished in DAPT-treated LMC motor neurons (Figure 4D, S4), indicating that inhibition of Notch signaling promotes specification of the early born LMCm neurons at the expense of later generated LMCl neurons (Sockanathan and Jessell, 1998).

Figure 4. Notch is required for MMC identity along the rostral-caudal axis of spinal cord.

A. In contrast to cervical spinal cord, motor neurons are organized into the Lhx3+/Foxp1− MMC and Lhx3−/Foxp1+ lateral motor columns (LMC) in brachial spinal cord. B-D’ Induction of Hoxc8 leads to adoption of brachial identity by differentiating motor neurons, including robust expression of LMC marker Foxp1. B-B’. Similar to cervical conditions, DAPT treatment in Hoxc8 induced cultures results in a dramatic downregulation in Lhx3 expression. C-C’. DAPT treatment in Hoxc8 conditions dramatically increases the number Foxp1+ LMC motor neurons. D-D’. DAPT treatment also leads to a robust downregulation in the expression of Lhx1, marker of the lateral division of the LMC column (LMCl) (See also Figure S4). Scale bar marks 100μm. E. Quantitative comparison of MMC (P<0.001), HMC (P=.45), and LMC (P=.002) motor neurons in control and DAPT-treated Hoxc8-induced day 6 EBs. Data reported as mean ± SEM (n=3). F. Motor neurons at thoracic level are organized into the Lhx3+/Foxp1− MMC and Lhx3−/Foxp1− HMC and Lhx3−/Foxp1low preganglionic (PGC) motor columns. G. Similar to cervical conditions, Hoxc9 induced cultures primarily produce motor neurons with Lhx3+ MMC identity. G-I’ Induction of Hoxc9 leads to adoption of thoracic identity manifested by the presence of PGC motor neurons expressing low levels of Foxp1. G’. DAPT treatment results in dramatic decrease in Lhx3 expression. H- I’. DAPT treatment increases the number of Lhx3−/Foxp1− HMC motor neurons as well as Hb9−/Foxp1low PGC motor neurons. Scale bar marks 100μm. J. Quantitative comparison of MMC (P=.004), HMC (P=.008), and PGC (P=.004) motor neurons in control and DAPT-treated Hoxc9-induced day 6 EBs. Data reported as mean ± SEM (n=3). K. Schematic depicting rostral-caudal appropriate changes in motor neuron subtype identity after Notch inactivation. In cervical (RA) and thoracic (Hoxc9) conditions, Notch inactivation primarily converts MMC motor neurons into HMC motor neurons. In contrast, Notch inactivation in brachial (Hoxc8) conditions leads to conversion of MMC motor neurons into LMC motor neurons. See also Figure S4.

We next explored the role of Notch signaling in thoracic spinal cord by analyzing motor column composition in inducible Hoxc9 motor neurons (Jung et al., 2010; Mazzoni et al., 2011) in the presence and absence of DAPT. Besides MMC and HMC motor neurons, thoracic spinal cord contains preganglionic sympathetic (PGC) motor neurons expressing low levels of Foxp1 in the absence of Hb9 (Thaler et al., 2004) (Figure 4F). We found that 51% of motor neurons in Hoxc9-induced cultures were Lhx3+, 4% were Foxp1+, and 45% were Lhx3−/Foxp1− (Figure 4G-H and J). The lack of Hb9 immunoreactivity indicated that Isl+/Foxp1+ motor neurons were likely PGC motor neurons (Figure 44H). DAPT treatment led to a down-regulation of Lhx3 from 51% to 16.5% of motor neurons (Figure 4G and J), accompanied by an increase in HMC motor neurons from 45% to 70% (Figure 4J), with a small but significant increase in PGC motor neurons from 4% to 13% (Figure I-J). The combined data indicate that Notch signaling is required for the maintenance of Lhx3 expression and MMC identity at all spinal levels. However, the subtype identity of neurons generated in the absence of Notch signaling depends on the rostro-caudal spinal position – in upper cervical and thoracic levels, MMC neurons are primarily respecified into HMC neurons, while at brachial level they primarily acquire LMCm identity (Figure 4K).

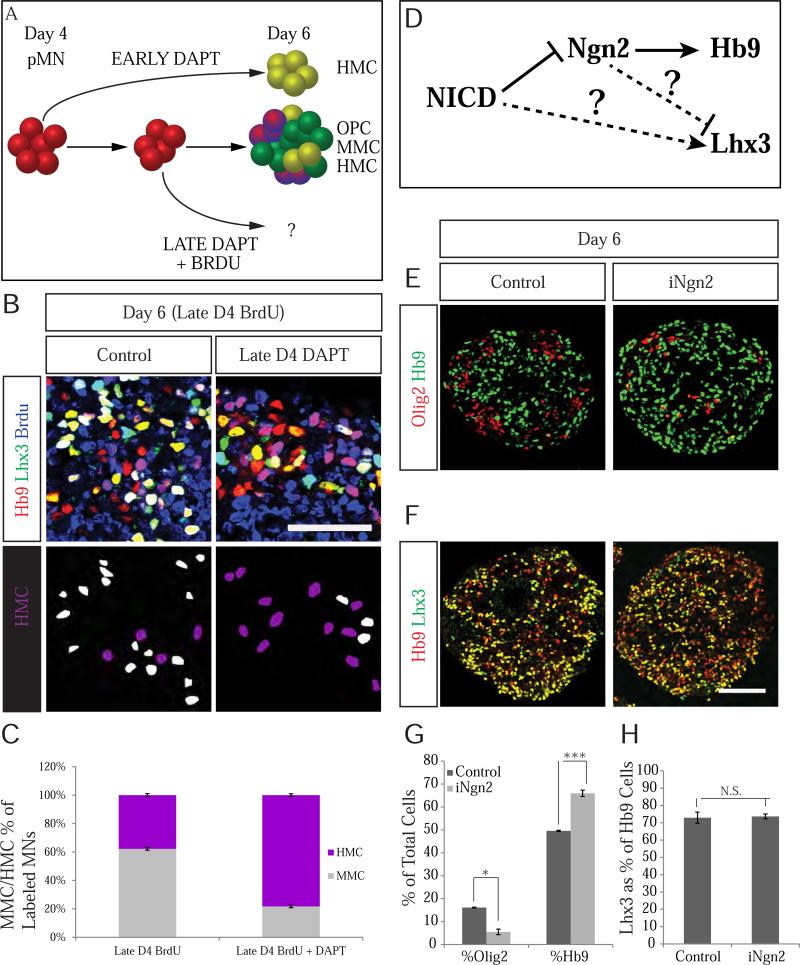

Notch controls the timing of neurogenesis and motor neuron subtype identity by independent mechanisms

Treatment of nascent motor neurons with DAPT on day 5 of differentiation failed to downregulate Lhx3 expression (Figure S3C-D), indicating that young postmitotic motor neurons are already committed to their columnar fate and are insensitive to Notch inactivation. To determine whether Notch inhibition controls motor neuron subtype identity indirectly through acceleration of motor neuron genesis, we examined effects of Notch inhibition during late stages of motor neuron production, when MMC neurons are primarily generated. Surprisingly, combining DAPT treatment with BrdU birthdating late on day 4 still revealed a significant decrease in Lhx3 expression from 62% to 21% in late born BrdU+ motor neurons (Figure 5A-C). This finding indicates that Notch inhibition promotes HMC identity irrespective of the timing of motor neuron production.

Figure 5. Notch signaling instructively specifies MMC identity.

A. Schematic highlighting approach to determine whether Notch controls columnar identity in a permissive or instructive manner. If Notch is permissive, then inhibition of Notch signaling at the late stages of differentiation should not significantly affect columnar identity of late born motor neurons. If Notch is instructive, then late Notch inactivation will still lead to increased HMC genesis. Differentiating cells were treated with BrdU and DAPT on the evening of day 4. Columnar identity of late born (BrdU+) motor neurons was determined by Lhx3 and Hb9 immunostaining. B. Late DAPT treatment leads to a robust reduction in MMC (white) motor neurons with a corresponding increase in HMC (purple) motor neurons. Scale bar marks 50μm. C. Quantification of MMC and HMC motor neurons in control and late DAPT treated day 6 EBs (P<0.001). Data reported as mean ± SEM (n=3). D. Schematic depicting alternate Ngn2-dependent and –independent pathways through which Notch potentially regulates motor neurons subtype identity. E. Similar to Notch inactivation by DAPT treatment or DnMaml1-eGFP overexpression, Ngn2 overexpression leads to increased motor neuron differentiation at the expense of Olig2+ progenitors. F. In contrast, Ngn2 overexpression has no effect on Lhx3 expression. Scale bar marks 100μm. G. Quantification of Olig2+ (P<.001) and Hb9+ (P=.006) in control versus Ngn2-induced day 6 EBs. Data reported as mean ± SEM (n=3) H. Quantification of Lhx3 in control versus Ngn2-induced motor neurons (P=.84). Data reported as mean ± SEM (n=5 from 3 EBs per differentiation). See also Figure S5.

Our finding that Notch effects on the timing of motor neuron genesis can be dissociated from its effects on motor neuron subtype specification prompted us to investigate whether the two developmental processes are controlled by divergent pathways. We observed a 3.3-fold increase in expression of a proneural gene Ngn2 in pMNs 12 hours after DAPT treatment (Figure S5A-C), indicating that upregulation of Ngn2 might mediate effects of Notch inhibition in pMNs (Figure 5D). To test this hypothesis, we generated an inducible ESC line carrying V5-tagged Ngn2. Induction of Ngn2 in day 4 progenitors (Figure S5D) revealed that similar to Notch inhibition, Ngn2 over-expression increased motor neuron yield from 49% to 65% (Figure 5E, G), and concomitantly decreased Olig2 from 15.8% to 5.5% (Figure 5E, G), indicating the Ngn2 is sufficient to drive neurogenic differentiation of pMNs. In contrast, quantification of Lhx3 expression in Ngn2-induced motor neurons revealed that Ngn2 overexpression had no significant effect of the columnar identity of generated motor neurons (Figure 5F, H). These data support the conclusion that timing of neurogenesis and control of motor neuron subtype identity are functionally independent processes regulated by molecularly distinct Notch targets.

Discussion

Several recent studies have started to address the function of Notch signaling in motor neuron subtype specification (Machado et al., 2014; Sabharwal et al., 2011). However, it remained unclear whether Notch acts primarily indirectly by controlling the timing of motor neuron genesis. Our results support a model in which Notch directly controls motor neuron subtype identity. First, we demonstrate that HMC generation peaks prior to MMC production in the ESC-to-motor neuron differentiation system. Second, we demonstrate that inhibition of Notch signaling leads to accelerated neurogenic differentiation of pMNs. Third, we find that Notch inhibition at late (preferentially MMC-producing) phase of cervical motor neuron genesis leads to overproduction of HMC motor neurons. This finding is incompatible with a model in which Notch controls neuronal subtype identity through the timing of motor neuron generation and supports the conclusion that activation of Notch signaling during or immediately after the final division of pMNs instructs differentiating motor neurons to acquire MMC identity. Furthermore, our observation that Notch manipulation results in a global respecification of pMN fate indicates that early Olig2 expressing progenitors are functionally multipotent.

We propose that the observed temporal changes in motor neuron subtype differentiation reflect changes in the signaling environment rather than intrinsic changes in pMN competence. Increased production of MMC neurons late in differentiation might reflect feedback signaling from Notch ligand Jag2-expressing postmitotic motor neurons (Marklund et al., 2010; Valsecchi et al., 1997). Besides Notch, other signals contribute to motor neuron subtype specification. Agalliu et al. demonstrated that overexpression of non-canonical Wnt4/5 induces MMC identity at the expense of HMC and LMC identity (Agalliu et al., 2009), raising the possibility that Wnt and Notch signals cooperate to specify MMC identity (Hayward et al., 2005; Hu et al., 2010; Koyanagi et al., 2007; Koyanagi et al., 2005).

Spinal motor neurons acquire finer subtype identity at limb level manifested as lateral and medial LMC divisions. Inhibition of Notch signaling in cells programmed to acquire limb level motor neuron identity by overexpression of Hoxc8 resulted in a striking downregulation of a lateral LMC marker Lhx1, indicating that Notch signaling is also required for specification of divisional motor neuron identity. Interestingly, Machado et al. recently demonstrated that activation of Notch signaling stratifies HMC motor neurons in cervical spinal cord to induce specification of phrenic motor neurons innervating the diaphragm (Machado et al., 2014). Jointly, these results support a hierarchical model, in which final motor neuron subtype identity is achieved by a series of cell fate decisions regulated by local Notch signaling in conjunction with other inductive signals, such as retinoids for LMCl (Sockanathan et al., 2003) and non-canonical Wnts for MMC specification. We propose that the Notch signaling pathway, conserved in all metazoans, has been repeatedly co-opted during the evolution of the motor system to increase neuronal diversity in step with the development of more complex body plans.

Experimental Procedures

Mouse ESC culture and MN differentiation

ESCs were cultured and differentiated into motor neurons as previously described (Wichterle and Peljto, 2008).

Induction of transgenes and DAPT treatment

Inducible ESC lines were generated as previously described (Mazzoni et al., 2011). New ESC lines generated for this study include inducible DnMaml1-eGFP, NICD-V5, and Ngn2-V5. To induce expression of transgenes in day 4 pMNs, doxycycline was added one day prior on day 3 at a concentration of 2μg/ml.

To inhibit Notch signaling in pMNs during MN differentiation, DAPT was added to the cultures at a final concentration of 5μg/ml (Calbiochem). To prevent precipitation, DAPT was pre-diluted in DMSO to a concentration of 5mg/ml.

Immunostaining

EBs were fixed, sectioned and processed for immunostaining as previously described (Novitch et al., 2001). Commercial antibodies used in this study include: Rabbit anti-Olig2 (Millipore, AB9610), mouse anti-V5 (Life Technologies, 46-0705), rat anti-Brdu (Accurate Chemical, OBT0030), mouse Hb9 (DSHB, 81.5C10), mouse anti Isl1/2 (DSHB, 39.4D5). Rabbit anti-Lhx1, rabbit anti-Lhx3, guinea pig Foxp1, guinea pig Olig2, and mouse Nkx2.2 were generously provided by Dr. Tom Jessell and Susan Morton (Arber et al., 1999; Briscoe et al., 2000; Dasen et al., 2008; Kania et al., 2000; Novitch et al., 2001). Mouse anti-Ngn2 was generously provided by Dr. David Anderson (Zhou et al., 2001). All images were acquired using a confocal laser microscope (LSM Zeiss Meta 510).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

RNA was initially extracted from pMNs using Trizol LS RNA extraction (Life Technologies), and further purified using RNeasy (Qiagen) spin column mini kits. cDNA was prepared by Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase per the manufacturer's instructions (Life Technologies). Samples were analyzed using SYBR green qRTPCR mix in MX3000P QPCR System (Stratagene).

Statistical analysis

Quantifications were reported as average ± standard error of mean (SEM). Statistical significance was calculated using two-tailed Student's t-test with unequal variance. Relevant p values were as follows: *p=0.01-0.05, **p=0.001-0.01, ***p<0.001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Thomas Jessell and Susan Morton for providing a number of antibodies that were critical for this study. We thank Warren Ewens for providing a DnMaml1-eGFP expression construct and Nicholas Gaiano for providing an NICD expression construct. We thank Phuong Hoang and Ho Sung Rhee for their insight and comments on the manuscript. We are grateful for Austin Wei for his graphic design expertise. G.C.T. was in part funded by NIH training grant (T32HD55165). This work was supported by Project ALS foundation, Target ALS and National Institutes of Health grant R01 NS-078097.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

All experiments were designed by HW and GCT. All experiments were performed by GCT. Inducible Hoxc8 and Hoxc9 ESC lines were generated by EOM.

References

- Agalliu D, Takada S, Agalliu I, McMahon AP, Jessell TM. Motor Neurons with Axial Muscle Projections Specified by Wnt4/5 Signaling. Neuron. 2009;61:708–720. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arber S, Han B, Mendelsohn M, Smith M, Jessell TM, Sockanathan S. Requirement for the homeobox gene Hb9 in the consolidation of motor neuron identity. Neuron. 1999;23:659–674. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shushan E, Feldman E, Reubinoff BE. Notch signaling regulates motor neuron differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Stem cells. 2015;33:403–415. doi: 10.1002/stem.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J, Ericson J. Specification of neuronal fates in the ventral neural tube. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:43–49. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J, Pierani A, Jessell TM, Ericson J. A homeodomain protein code specifies progenitor cell identity and neuronal fate in the ventral neural tube. Cell. 2000;101:435–445. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JA, Huang YP, Mazzoni EO, Tan GC, Zavadil J, Wichterle H. Mir-17-3p controls spinal neural progenitor patterning by regulating olig2/irx3 cross-repressive loop. Neuron. 2011;69:721–735. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasen JS, De Camilli A, Wang B, Tucker PW, Jessell TM. Hox Repertoires for Motor Neuron Diversity and Connectivity Gated by a Single Accessory Factor, FoxP1. Cell. 2008;134:304–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasen JS, Liu JP, Jessell TM. Motor neuron columnar fate imposed by sequential phases of Hox-c activity. Nature. 2003;425:926–933. doi: 10.1038/nature02051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessaud E, McMahon AP, Briscoe J. Pattern formation in the vertebrate neural tube: a sonic hedgehog morphogen-regulated transcriptional network. Development. 2008;135:2489–2503. doi: 10.1242/dev.009324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson J, Briscoe J, Rashbass P, van Heyningen V, Jessell TM. Graded sonic hedgehog signaling and the specification of cell fate in the ventral neural tube. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1997;62:451–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Campmany L, Stam FJ, Goulding M. From circuits to behaviour: motor networks in vertebrates. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward P, Brennan K, Sanders P, Balayo T, DasGupta R, Perrimon N, Martinez Arias A. Notch modulates Wnt signalling by associating with Armadillo/beta-catenin and regulating its transcriptional activity. Development. 2005;132:1819–1830. doi: 10.1242/dev.01724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori K, Sen A, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Notch signaling at a glance. Journal of cell science. 2013;126:2135–2140. doi: 10.1242/jcs.127308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Lefort K, Qiu W, Nguyen BC, Rajaram RD, Castillo E, He F, Chen Y, Angel P, Brisken C, et al. Control of hair follicle cell fate by underlying mesenchyme through a CSL-Wnt5a-FoxN1 regulatory axis. Genes & development. 2010;24:1519–1532. doi: 10.1101/gad.1886910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H, Lacombe J, Mazzoni EO, Liem KF, Jr., Grinstein J, Mahony S, Mukhopadhyay D, Gifford DK, Young RA, Anderson KV, et al. Global control of motor neuron topography mediated by the repressive actions of a single hox gene. Neuron. 2010;67:781–796. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kania A, Johnson RL, Jessell TM. Coordinate roles for LIM homeobox genes in directing the dorsoventral trajectory of motor axons in the vertebrate limb. Cell. 2000;102:161–173. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyanagi M, Bushoven P, Iwasaki M, Urbich C, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Notch signaling contributes to the expression of cardiac markers in human circulating progenitor cells. Circulation research. 2007;101:1139–1145. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.151381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyanagi M, Haendeler J, Badorff C, Brandes RP, Hoffmann J, Pandur P, Zeiher AM, Kuhl M, Dimmeler S. Non-canonical Wnt signaling enhances differentiation of human circulating progenitor cells to cardiomyogenic cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:16838–16842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500323200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesey FJ, Cepko CL. Vertebrate neural cell-fate determination: lessons from the retina. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2:109–118. doi: 10.1038/35053522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado CB, Kanning KC, Kreis P, Stevenson D, Crossley M, Nowak M, Iacovino M, Kyba M, Chambers D, Blanc E, et al. Reconstruction of phrenic neuron identity in embryonic stem cell-derived motor neurons. Development. 2014;141:784–794. doi: 10.1242/dev.097188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillard I, Weng AP, Carpenter AC, Rodriguez CG, Sai H, Xu L, Allman D, Aster JC, Pear WS. Mastermind critically regulates Notch-mediated lymphoid cell fate decisions. Blood. 2004;104:1696–1702. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marklund U, Hansson EM, Sundstrom E, de Angelis MH, Przemeck GK, Lendahl U, Muhr J, Ericson J. Domain-specific control of neurogenesis achieved through patterned regulation of Notch ligand expression. Development. 2010;137:437–445. doi: 10.1242/dev.036806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masahira N, Takebayashi H, Ono K, Watanabe K, Ding L, Furusho M, Ogawa Y, Nabeshima Y, Alvarez-Buylla A, Shimizu K, et al. Olig2-positive progenitors in the embryonic spinal cord give rise not only to motoneurons and oligodendrocytes, but also to a subset of astrocytes and ependymal cells. Dev Biol. 2006;293:358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni EO, Mahony S, Iacovino M, Morrison CA, Mountoufaris G, Closser M, Whyte WA, Young RA, Kyba M, Gifford DK, et al. Embryonic stem cell-based mapping of developmental transcriptional programs. Nat Methods. 2011;8:1056–1058. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizeracka K, DeMaso CR, Cepko CL. Notch1 is required in newly postmitotic cells to inhibit the rod photoreceptor fate. Development. 2013;140:3188–3197. doi: 10.1242/dev.090696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moohr OL. Character changes caused by mutation of an entire region of a chromosome in Drosophila. Genetics. 1919;4:275–278. doi: 10.1093/genetics/4.3.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukouyama YS, Deneen B, Lukaszewicz A, Novitch BG, Wichterle H, Jessell TM, Anderson DJ. Olig2+ neuroepithelial motoneuron progenitors are not multipotent stem cells in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1551–1556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510658103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BR, Hartman BH, Georgi SA, Lan MS, Reh TA. Transient inactivation of Notch signaling synchronizes differentiation of neural progenitor cells. Dev Biol. 2007;304:479–498. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novitch BG, Chen AI, Jessell TM. Coordinate regulation of motor neuron subtype identity and pan-neuronal properties by the bHLH repressor Olig2. Neuron. 2001;31:773–789. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00407-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novitch BG, Wichterle H, Jessell TM, Sockanathan S. A requirement for retinoic acid-mediated transcriptional activation in ventral neural patterning and motor neuron specification. Neuron. 2003;40:81–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peljto M, Dasen JS, Mazzoni EO, Jessell TM, Wichterle H. Functional diversity of ESC-derived motor neuron subtypes revealed through intraspinal transplantation. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng CY, Yajima H, Burns CE, Zon LI, Sisodia SS, Pfaff SL, Sharma K. Notch and MAML signaling drives Scl-dependent interneuron diversity in the spinal cord. Neuron. 2007;53:813–827. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabadan MA, Cayuso J, Le Dreau G, Cruz C, Barzi M, Pons S, Briscoe J, Marti E. Jagged2 controls the generation of motor neuron and oligodendrocyte progenitors in the ventral spinal cord. Cell death and differentiation. 2012;19:209–219. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos C, Rocha S, Gaspar C, Henrique D. Two Notch ligands, Dll1 and Jag1, are differently restricted in their range of action to control neurogenesis in the mammalian spinal cord. PloS one. 2010;5:e15515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha SF, Lopes SS, Gossler A, Henrique D. Dll1 and Dll4 function sequentially in the retina and pV2 domain of the spinal cord to regulate neurogenesis and create cell diversity. Dev Biol. 2009;328:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabharwal P, Lee C, Park S, Rao M, Sockanathan S. GDE2 regulates subtype-specific motor neuron generation through inhibition of Notch signaling. Neuron. 2011;71:1058–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sockanathan S, Jessell TM. Motor neuron-derived retinoid signaling specifies the subtype identity of spinal motor neurons. Cell. 1998;94:503–514. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81591-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sockanathan S, Perlmann T, Jessell TM. Retinoid receptor signaling in postmitotic motor neurons regulates rostrocaudal positional identity and axonal projection pattern. Neuron. 2003;40:97–111. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussel L, Marin O, Kimura S, Rubenstein JL. Loss of Nkx2.1 homeobox gene function results in a ventral to dorsal molecular respecification within the basal telencephalon: evidence for a transformation of the pallidum into the striatum. Development. 1999;126:3359–3370. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.15.3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaler JP, Koo SJ, Kania A, Lettieri K, Andrews S, Cox C, Jessell TM, Pfaff SL. A postmitotic role for Isl-class LIM homeodomain proteins in the assignment of visceral spinal motor neuron identity. Neuron. 2004;41:337–350. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida T, Ensini M, Morton SB, Baldassare M, Edlund T, Jessell TM, Pfaff SL. Topographic organization of embryonic motor neurons defined by expression of LIM homeobox genes. Cell. 1994;79:957–970. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udolph G. Notch signaling and the generation of cell diversit in Drosophila neuroblast lineages. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2012;727:47–107. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0899-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valsecchi C, Ghezzi C, Ballabio A, Rugarli EI. JAGGED2: a putative Notch ligand expressed in the apical ectodermal ridge and in sites of epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. Mechanisms of development. 1997;69:203–207. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichterle H, Lieberam I, Porter JA, Jessell TM. Directed differentiation of embryonic stem cells into motor neurons. Cell. 2002;110:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00835-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichterle H, Peljto M. Differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells to spinal motor neurons. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1002/9780470151808.sc01h01s5. Chapter 1, Unit 1H 1 1-1H 1 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Aster JC, Blacklow SC, Lake R, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Griffin JD. MAML1, a human homologue of Drosophila mastermind, is a transcriptional co-activator for NOTCH receptors. Nature genetics. 2000;26:484–489. doi: 10.1038/82644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Anderson DJ. The bHLH transcription factors OLIG2 and OLIG1 couple neuronal and glial subtype specification. Cell. 2002;109:61–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00677-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Choi G, Anderson DJ. The bHLH transcription factor Olig2 promotes oligodendrocyte differentiation in collaboration with Nkx2.2. Neuron. 2001;31:791–807. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00414-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.