Abstract

Peptides containing α,α-dialkylated α-amino acids, owing to their ability to disrupt aggregation of β-amyloid proteins, have therapeutic potential in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Thermodynamic and structural analyses are reported for a series of β-hairpin peptides containing α,α-dialkylated α-amino acids with varying side-chain lengths. Results of these experiments show that α,α-dialkylated α-amino acids with side-chain lengths longer than one carbon unit are tolerated in a β-hairpin, although at a moderate cost to folded stability.

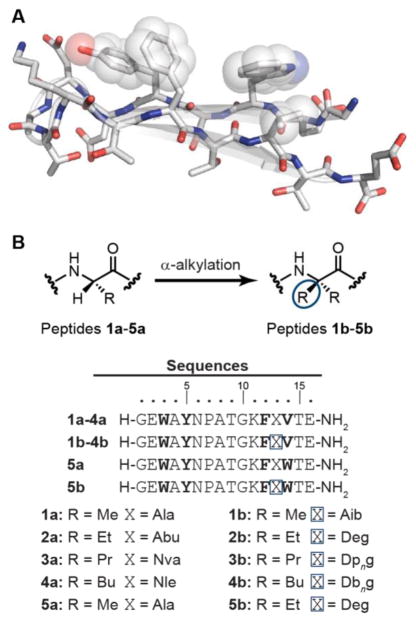

Graphical Abstract

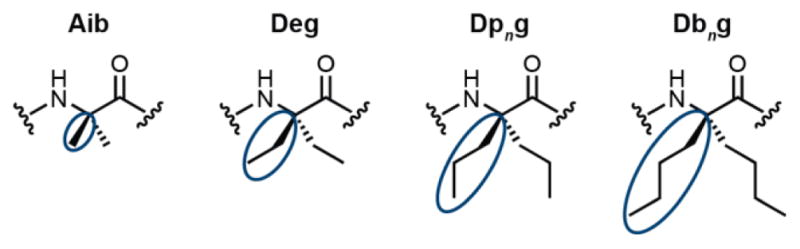

α-Amino acids bearing two alkyl substituents at Cα are common building blocks in peptide-based natural products1–3 as well as synthetic peptidomimetics.4 α-Aminoisobutyric acid (Aib, Figure 1), the most well-studied α,α-dialkylated α-amino acid, strongly promotes helical secondary structures5 and can act as a “β-breaker,” significantly disfavoring β-sheet formation.6 In cases where Aib has been examined in sheet secondary structure contexts, it can also act as a tight turn inducer.7,8 Chiral Cα-Me-residues are also excellent helix stabilizers, even when the parent α-amino acid typically favors sheet (e.g., (αMe)Val vs. Val).9 In contrast to Aib and related (αMe)α-residues, a number of symmetric α,α-dialkylated α-amino acids bearing bulkier substituents can promote fully-extended backbone conformations.10 For example, small homooligomers of diethylglycine (Deg) and di-n-propylglycine (Dpng) have been shown to form fully-extended chains both in solution and the solid state.11–15 Seeking to leverage this precedent toward biomedical application, recent studies have shown that strategic incorporation of bulky α,α-dialkylated amino acids (e.g., diisobutylglycine, dibenzylglycine, di-n-propylglycine) into short β-strands can cap growing β-sheets, preventing formation of amyloid fibrils and even promoting their disassembly.16–18

Figure 1.

Examples of symmetric α,α-dialkylated α-residues: α-aminoisobutyric acid (Aib), diethylglycine (Deg), di-n-propylglycine (Dpng), and di-n-butylglycine (Dbng). The additional side chains of the α,α-dialkylated α-amino acids are circled.

While the structural studies described above indicate that α,α-dialkylated α-amino acids can promote extended conformations in peptides, the thermodynamic impact of such modifications in the biologically relevant context of aqueous medium has not been investigated. Addressing this gap in knowledge would improve fundamental understanding of the role of α,α-dialkylated α-amino acid side-chain identity in promoting β-sheet folds. Such knowledge, in turn, could enable applications related to amyloid inhibition by identifying residues that not only promote folding and facilitate tight binding to the exposed end of a β-sheet but also prevent the next strand from docking to the growing aggregate. Based on the precedent detailed above, we hypothesized that side-chain steric bulk could be optimized to achieve this end. Thus, we set out in the present work to systematically examine the structural and thermodynamic consequences of incorporation of four different achiral symmetric α,α-dialkylated α-residues (Figure 1) in the context of a β-hairpin fold.

We chose peptide 1a (Figure 2) as a host in which to explore the above questions. This 16-residue sequence (Figure 2a), derived from the C-terminal hairpin of protein GB1,19,20 consists of two anti-parallel β-strands connected by a four-residue (PATG) turn. All modifications to 1a were made at Ala13, the central residue in the C-terminal strand of the β-hairpin. This position was selected based on two lines of reasoning. First, because Ala13 is at a non-hydrogen-bonding site, substitution with dialkylated α-residues will not disrupt intrastrand backbone interactions necessary for folding; this increases the relevance of results to inform the use of dialkylated residues to disrupt β-sheet-mediated aggregation. Second, modifications to the side chain at Ala13 will not alter the hydrophobic core of the folded hairpin consisting of residues Trp3, Tyr5, Phe12, and Val14.

Figure 2.

(A) Folded structure of the C-terminal hairpin from protein GB1 (PDB: 2QMT).21 Side chains of hydrophobic core residues are indicated with spheres. (B) Sequences of peptides 1a–5a and 1b–5b. α,α-Dialkylated α-residues are indicated with blue boxes and the hydrophobic core in bold.

In order to systematically probe the relationship between steric bulk in α,α-dialkylated α-residues and β-sheet forming propensity, we synthesized the series of peptides 1b–4b (Figure 2b). These sequences incorporate one of four α,α-dialkylated α-residues in place of Ala13 in 1a: Aib in 1b, diethylglycine (Deg) in 2b, di-n-propylglycine (Dpng) in 3b, and di-n-butylglycine (Dbng) in 4b. To isolate any effects of increasing side-chain length and hydrophobicity on folding, we prepared additional control sequences where Ala13 was replaced with monoalkylated residues α-aminobutyric acid (2a), norvaline (3a), or norleucine (4a). Peptides 2a–4a and 1b–4b were synthesized using standard Fmoc solid-phase methods, purified by preparative HPLC, and the identity and purity of each sequence confirmed by MALDI-MS and analytical HPLC (see Supporting Information).

We first assessed the folding behavior of control peptides 1a–4a by multidimensional NMR (TOCSY, NOESY, and COSY) at 278 K in 50 mM phosphate buffer (9:1 H2O/D2O, pH 6.3 uncorrected for presence of D2O). Spectral data for peptide 1a were previously reported under identical conditions.20 The magnitude of chemical shift separation (Δδ) between the two diastereotopic protons found in glycine residues near the turn of a β-hairpin-forming peptide can be used as a spectroscopic handle to quantify folded population.22 Thus, we assigned the chemical shifts of the HN and Hα resonances from Gly10 in 1a–4a (Table S2) and used these data to calculate the Δδ and folded population for each sequence. A reference Δδ value of 0.310 ppm was used for the fully folded state in these calculations based on data previously reported for a disulfide-cyclized variant of 1a.20 The folded populations and corresponding ΔGfold values for peptides 1a–4a are identical within experimental uncertainty (Table 1). These data indicate that, despite increasing relative hydrophobicity of the residues in question, increasing the length of the side chain at position 13 in this peptide sequence has little or no impact on β-hairpin folded stability.

Table 1.

Folding Thermodynamics of Peptides 1a–4a at 278 K and Peptides 5a and 1b–5b at 298 K.

| peptide | temperature (K) | ΔδGly10 (ppm) | fraction foldeda | ΔGfold (kcal/mol)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 278 | 0.202 | 0.66 ± 0.06 | −0.4 ± 0.1 |

| 2a | 278 | 0.201 | 0.66 ± 0.06 | −0.4 ± 0.1 |

| 3a | 278 | 0.208 | 0.68 ± 0.06 | −0.4 ± 0.1 |

| 4a | 278 | 0.209 | 0.68 ± 0.06 | −0.4 ± 0.1 |

|

| ||||

| 1ab | 293 | 0.185 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | −0.2 ± 0.1 |

| 1b | 298 | 0.026 | 0.08 ± 0.05 | +1.41 ± 0.04 |

| 2b | 298 | 0.080 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | +0.6 ± 0.1 |

| 3b | 298 | 0.083 | 0.27 ± 0.05 | +0.6 ± 0.1 |

| 4b | 298 | 0.091 | 0.29 ± 0.05 | +0.5 ± 0.2 |

|

| ||||

| 5a | 298 | 0.310 | 1.01 ± 0.07 | N/A |

| 5b | 298 | 0.151 | 0.49 ± 0.05 | +0.0 ± 0.04 |

Error propagated assuming 0.010 ppm uncertainty in chemical shift assignments.

Previously reported at 293 K.20 Included for comparison purposes.

We next examined the peptide series 1b–4b under identical conditions. We noted poor solubility of these peptides at 278 K, which we attribute to the added hydrophobicity from the α,α-dialkylated α-residues at a solvent-exposed position in the hairpin. At a higher temperature of 298 K, the samples were fully homogeneous and spectra showed clear splitting of HN resonances (Figure S1), supporting the absence of aggregation. Thus, we proceeded with the analysis of folded population based on glycine Hα chemical shifts at the higher temperature (Table 1). Previously reported data are provided for peptide 1a at 293 K to facilitate comparison.20

The NMR data for 1b–4b support the hypothesis that increasing steric bulk in the dialkylated α-residue beyond the size of a methyl group shifts the equilibrium to favor sheet secondary structure. As expected, substitution of Ala13 in 1a with Aib in 1b almost completely abolishes the β-hairpin fold. Replacing the Aib in 1b with Deg in 2b boosts the folded population to ~26%. Interestingly, increasing the steric bulk beyond Deg in 2b to Dpg in 3b and Dbg in 4b had no additional effect on folded population. In all cases, the folds of peptides bearing alkylated residues are destabilized relative to control peptide 1a. This destabilization may be caused by a loss of chirality in the backbone; in a recent study carried out in the context of a helix in a small protein, it was demonstrated that such a loss of chirality can lead to an entropic destabilization of the folded state.23

Collectively, the NMR data obtained for 1b–4b show that (1) consistent with precedent, the dialkylated α-amino acid Aib is a strong sheet breaker; (2) extending the size of the side chain from methyl to ethyl partially mitigates this effect; (3) increasing the size of the linear dialkylated side chain beyond two carbon units has no measurable impact on folding; and (4) none of the dialkylated α-residues promote sheet formation as effectively as a protein α-amino acid. These results are in line with previously published conformational studies of homopolymers comprised of α,α-dialkylated α-amino acids.10,24,25

One possible origin of the destabilization seen in peptides 2b–4b is that the folded structure in these sequences is fundamentally different than that of the host β-hairpin. In order to test this hypothesis, we pursued the high-resolution structure of a hairpin bearing an α,α-dialkylated α-residue. The low folded populations of peptides 2b–4b under conditions in which they were soluble precluded direct structural analysis. In order to circumvent this issue, we made mutations elsewhere in the sequence to further stabilize the hairpin fold. It has been shown that introducing a “tryptophan zipper” motif into sequences similar to 1a dramatically increases the folded stability of the β-hairpin.26 Thus, we prepared peptide 5a (Figure 2), which contains a Val14-to-Trp mutation relative to 1a, and peptide 5b, which contains the same Val14-to-Trp mutation in the context of Deg-containing sequence 2b. As there was no significant difference between the folded populations of peptides containing Deg, Dpng, or Dbng, we anticipated results for Deg would prove broadly informative.

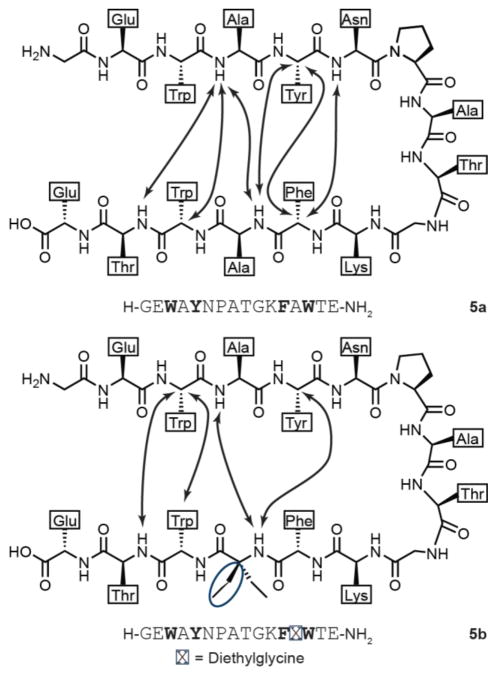

We carried out multidimensional NMR on peptides 5a and 5b at 298 K and assigned the backbone (Tables S3, S4) and side-chain resonances for each. Glycine diastereotopic Hα chemical shifts (Table 1) suggested that the folded population of 5a was indistinguishable from that of a disulfide-cyclized variant of 1a reported in a previous study.20 This result shows that the introduction of tryptophan at position 14 had the intended stabilizing effect. The corresponding analysis of peptide 5b indicated a folded population of 49%, a significant increase relative to peptide 2b. The fact that Val14-to-Trp substitution had the same apparent stabilizing effect on 1a and 2b supports the hypothesis that these two peptides (as well as 5a and 5b) adopt similar hairpin folds. To provide more direct evidence bearing on this question, we examined the folded structures of 5a and 5b through detailed NOE analysis. Overlap of side-chain resonances prevented unambiguous assignment of some NOEs; however, we were able to locate several long-range contacts in both sequences consistent with the expected β-hairpin folded conformation (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

NOE analysis of peptides 5a and 5b. Arrows indicate the presence of cross-strand NOEs consistent with a β-hairpin folded conformation. The additional side chain of the α,α-dialkylated α-amino acid is circled.

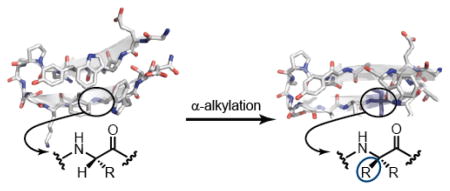

Encouraged by these results, we carried out simulated annealing with NMR-derived distance restraints to calculate high-resolution folded structures of 5a and 5b.27,28 For each peptide, we used unambiguous NOE signals to tabulate a set of inter-residue distance restraints (Tables S5, S6). These restraints were used to generate ensembles of three-dimensional structures which converged to β-hairpin conformations for both peptides (Figure S4). After confirming the hydrogen-bond register for 5a and 5b in preliminary simulations, we added additional distance restraints to enforce the corresponding inter-strand hydrogen bonds and generated new ensembles. We used the ten lowest energy structures from each ensemble (Figure S5) to calculate average NMR structures for the two peptides (Figure 4).

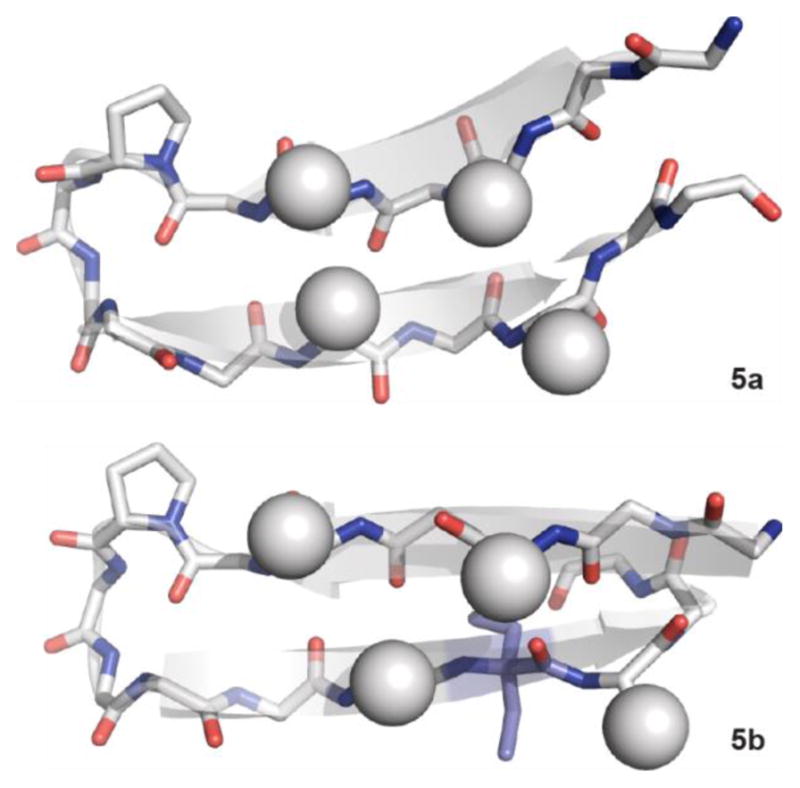

Figure 4.

NMR structures of peptides 5a and 5b. Spheres represent the side-chains of hydrophobic core residues Trp3, Tyr5, Phe12, and Trp14. The α,α-dialkylated α-amino acid in 5b is colored purple.

The NMR structures show that 5a and 5b both adopt similar canonical β-hairpin folds. Despite destabilization caused by inclusion of the α,α-dialkylated α-residue, the folded state of 5b appears very similar to that of peptide 5a. For comparison of these hairpins to a typical protein β-sheet, we calculated root-mean square deviation (RMSD) values for the backbone overlay of peptides 5a and 5b to the C-terminal hairpin of protein GB1, the origin of sequence 1a (Figure S6).21 Both natural peptide 5a and variant 5b bearing a Deg residue aligned well with the full length protein (RMSD 0.866 Å and 1.347 Å, respectively). That fact that the RMSD values for the two sequences are similar indicates that the presence of the α,α-dialkylated α-residue, while energetically destabilizing, does not significantly perturb the β-hairpin fold.

In summary, we have shown for first time the thermodynamic consequences of incorporating α,α-dialkylated α-amino acids into a β-sheet context in aqueous medium. Symmetric α,α-dialkylated α-amino acids with linear side chains can be accommodated into a β-hairpin secondary structure, albeit with accompanying destabilization of the folded structure, potentially limiting therapeutic efficacy in peptides containing these residues. The possibility exists that further fine-tuning of side chain structure may minimize this destabilization or perhaps even reverse it. We hypothesize that these ends may be achieved by examining chiral α,α-dialkylated α-residues or by utilizing more diverse side chains; homopolymers of β-branched α,α-dialkylated α-amino acids, for example, have shown the ability to template sheet formation.29 Work towards these ends is ongoing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Slippery Rock University and by the National Institutes of Health (R01GM107161 to W.S.H.).

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Experimental methods, supplemental figures, supplemental tables (PDF)

References

- 1.Duclohier H. Chem Biodivers. 2007;4:1023. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toniolo C, Brückner H. Chem Biodiv. 2007;4:1021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brückner H, Toniolo C. Chem Biodiv. 2013;10:731. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201300139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benedetti E. Biopolymers. 1996;40:3. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0282(1996)40:1<3::aid-bip2>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karle IL, Balaram P. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6747. doi: 10.1021/bi00481a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moretto V, Crisma M, Bonora GM, Toniolo C, Balaram H, Balaram P. Macromolecules. 1989;22:2939. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aravinda S, Shamala N, Balaram P. Chem Biodiv. 2008;5:1238. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200890112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu L, McElheny D, Setnicka V, Hilario J, Keiderling TA. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Bioinf. 2012;80:44. doi: 10.1002/prot.23140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valle G, Crisma M, Toniolo C, Polinelli S, Boesten WHJ, Schoemaker HE, Meijer EM, Kamphuis J. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1991;37:521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peggion C, Moretto A, Formaggio F, Crisma M, Toniolo C. Biopolymers. 2013;100:621. doi: 10.1002/bip.22267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toniolo C, Benedetti E. Macromolecules. 1991;24:4004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toniolo C, Bonora GM, Bavoso A, Benedetti E, Di Blasio B, Pavone V, Pedone C, Barone V, Lelj F, Leplawy MT, Kaczmarek K, Redlinski A. Biopolymers. 1988;27:373. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benedetti E, Di Blasio B, Pavone V, Pedone C, Bavoso A, Toniolo C, Bonora GM, Leplawy MT, Hardy PM. J Biosci. 1985;8:253. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barone V, Lelj F, Bavoso A, Di Blasio B, Grimaldi P, Pavone V, Pedone C. Biopolymers. 1985;24:1759. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonora GM, Toniolo C, Di Blasio B, Pavone V, Pedone C, Benedetti E, Lingham I, Hardy P. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:8152. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etienne MA, Aucoin JP, Fu Y, McCarley RL, Hammer RP. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3522. doi: 10.1021/ja0600678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bett CK, Ngunjiri JN, Serem WK, Fontenot KR, Hammer RP, McCarley RL, Garno JC. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2010;1:608. doi: 10.1021/cn100045q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bett CK, Serem WK, Fontenot KR, Hammer RP, Garno JC. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2010;1:661. doi: 10.1021/cn900019r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fesinmeyer RM, Hudson FM, Andersen NH. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7238. doi: 10.1021/ja0379520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lengyel GA, Horne WS. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:15906. doi: 10.1021/ja306311r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frericks Schmidt HL, Sperling LJ, Gao YG, Wylie BJ, Boettcher JM, Wilson SR, Rienstra CM. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:14362. doi: 10.1021/jp075531p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fesinmeyer RM, Hudson FM, Olsen K, White GN, Euser A, Andersen N. J Biomol NMR. 2005;33:213. doi: 10.1007/s10858-005-3731-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tavenor NA, Reinert ZE, Lengyel GA, Griffith BD, Horne WS. Chem Commun. 2016;52:3789. doi: 10.1039/c6cc00273k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toniolo C, Crisma M, Formaggio F, Peggion C. Biopolymers. 2001;60:396. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2001)60:6<396::AID-BIP10184>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka M. Chem Pharm Bull. 2007;55:349. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cochran AG, Skelton NJ, Starovasnik MA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091100898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang J-S, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Acta Crystallogr Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunger AT. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2728. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Simone G, Lombardi A, Galdiero S, Nastri F, Di Costanzo L, Gohda S, Sano A, Yamada T, Pavone V. Biopolymers. 2000;53:182. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(200002)53:2<182::AID-BIP8>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.