Abstract

Stroke disability is the only major disease without an effective treatment. The substantial clinical burden of stroke in disabled survivors and the lack of a medical therapy that promotes recovery provide an opportunity to explore the use of biomaterials to promote brain repair after stroke. Hydrogels can be injected as a liquid and solidify in situ to form a gelatinous solid with similar mechanical properties to the brain. These biomaterials have been recently explored to generate pro-repair environments within the damaged organ. This review highlights the clinical problem of stroke treatment and discusses recent advances in using in situ forming hydrogels for brain repair.

Introduction

Stroke is the leading cause of adult disability in the US and the third cause of death worldwide [1]. Ischemic stroke is caused by the occlusion of a vascular structure within the brain and an unsuccessful attempt of the body to establish reperfusion. The subsequent brain injury develops from a complex series of pathological events such as depolarization, inflammation and excitotoxicity [2]. These phenomena dramatically compromise the stability of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and activate the release of free radicals and proteases which not only lead to local cell death but also deepen and extend the injury. Unlike other organ tissues, brain tissue responds to ischemia in a very unique way; while the core of the infarct is immediately and irreversibly damaged and the associated neurological function is immediately impaired, the boundaries of the core expand to the adjacent tissue over the course of days, spreading apoptotic death to a region that was initially distal from the occluded vessel and healthy at the stroke onset. Promoting tissue regeneration at the site of a wound that is dynamic in space and time represents one of the biggest challenges in regenerative medicine, as stroke treatment is currently facing very limited therapeutic approaches and an extensive series of unsuccessful clinical trials [3]. In this article, the pathobiology of ischemic stroke, the current treatment approaches and the latest hydrogel-based therapeutic strategies used to promote brain repair will be presented and discussed. For more comprehensive reviews for biomaterial approaches in the central nervous system, please see [4].

1. Post-stroke endogenous repair mechanisms

Stroke patients show some degree of recovery over time independent of the treatment chosen. Below, we present the main endogenous repair mechanisms activated after stroke: inflammation, neurogenesis and angiogenesis.

1.1 Inflammation-induced cavity

The massive cell death that occurs following stroke results in the activation of local inflammatory cells or microglia [5], the expression and activation of extracellular matrix (ECM)-degrading enzymes (e.g. matrix metalloproteinases, hyaluronidases, serine proteases, etc.) and the loss of mechanical integrity of the damaged tissue [6]. In order to limit this matrix degradation to the boundaries of the stroke, astrocytes undergo an extensive morphology remodeling and extend processes around the lesion to form a scar [7] that compartmentalizes the degraded tissue within a physical empty cavity. Thus, cells attempting to infiltrate the stroke cavity are faced with a physical barrier and a landscape that is not amenable to migration because it is much softer and less elastic than normal brain [6] and is likely lacking in the natural ECM integrin ligands, fibers and structural features necessary for cell migration. Recently, a positive correlation was found between the thickness of this astrocytic scar and the stroke severity as the accumulation of astrocytes around the stroke site jeopardizes the infiltration of regenerative cells [8].

1.2 Neurogenesis

A major advance within the past decade has been the discovery of ongoing adult neurogenesis, defined by a continuous proliferation and maintenance of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) along the ventricles and in the hippocampus [9]. Under normal conditions, these newborn neurons migrate toward the hippocampus and the olfactory bulb. However, stroke damage was shown to increase NPC proliferation and re-route them towards the damaged site [9]. Whether these NPCs fully differentiate and contribute to stroke patient's functional recovery remains uncertain as the majority of newborn neuroblasts die prematurely within their migratory path.

1.3 Local angiogenesis

Experimental and clinical studies show that enhanced vessel formation and restored perfusion at the ischemic border correlate with improved long-term functional recovery and longer survival of stroke patients [10]. Measurements of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) levels in both serum and brain tissue of stroke patients showed a positive correlation between the severity of damage and the concentration of the growth factor, suggesting its involvement in the subsequent repair process resulting in recovery [11]. Interestingly, post-stroke neurogenesis and angiogenesis are tightly linked. Indeed, the specific inhibition of vascular growth worsens both neurogenesis and the neurological deficit, leading the path for a new approach based on the administration of VEGF to promote brain tissue regeneration [12].

2. Current therapeutic strategies

The only FDA-approved treatments in stroke focus on acute brain injury by promoting reperfusion. These approaches include direct clot lysis with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and endovascular stent/retrievers, which have shown substantial clinical trial success and are likely to be soon approved for use [13]. However, these approaches can only benefit a small percentage of stroke patients, as the currently approved therapeutic window is reduced to few hours after the stroke onset, leaving behind a large portion of untreated stroke patients. To date, no medical therapy that promotes repair and recovery in this disease has been found. Rehabilitation approaches, such as physical, occupation or speech therapy, are used to help patients mobility but have resulted in limited recovery after stroke [14].

Ongoing experimental and clinical studies to treat the stroke brain include the use of stem cells but also proneurogenic and angiogenic growth factors to regenerate the lost tissue. Stem or progenitor cell transplantation after stroke was shown to promote recovery in pre-clinical models. However, these studies are limited by poor survival of the transplant when administered as a suspended form into the damaged brain due to the immunological attack and the abrupt withdrawal of growth factor and adhesive support [15]. Transplanted NPCs that do survive often remain in an undifferentiated state [15]. Pro-angiogenic approaches were also tested with the systemic or intracerebral delivery of soluble VEGF and were shown to be unsuccessful. Indeed, the early administration of VEGF after stroke increases BBB opening, worsens edema, and promote the formation of disorganized and immature vasculature while its antagonist reduces the injury [16].

The substantial clinical burden of stroke in disabled survivors and the lack of a medical therapy that promotes recovery provide an opportunity to explore the use in situ tissue regeneration strategies to promote brain repair after stroke.

3. General tissue engineering approach using hydrogels

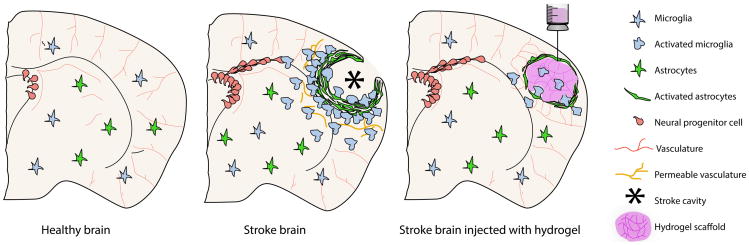

Classical tissue engineering strategies involve the ex vivo generation of engineered organs that can be implanted to substitute the lost tissue. However, this approach is not well suited for brain repair because it requires the invasive implantation of the tissue construct and it is unclear if functional brain tissue could be engineered/produced ex vivo. In situ tissue regeneration aims to completely bypass the ex vivo generation of the engineered organ by implanting a scaffold directly at the site of injury in order to stimulate endogenous tissue repair through the use of local or transplanted progenitors. Although early materials for brain repair utilized implantable materials [17,18], recent efforts have focused on engineered injectable hydrogels that can be directly transplanted within the stroke cavity for a minimally invasive procedure [19]. The hydrogels can be designed to match the mechanical properties of the normal brain by modulating the crosslinking density and to serve as local drug delivery depots (Figure 1). Hydrogels are formed by reducing the mobility of water-swollen polymers via the introduction of physical and/or covalent bonds between polymer chains, creating a crosslinked network. Depending on the polymer chain length and its tendency to coil and percolate, the crosslinking point and network mesh size can be modulated, which in turn modulates nutrient diffusion and cell motility.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of a coronal brain section and the major physiopathological events occurring after an ischemic stroke. In order to protect the healthy parenchyma from nearby lesion area, star-shaped glial cells, astrocytes, elongate cytosolic processes to surround the damaged site, forming the astrocytic scar. The long-term persisting peri-lesion scar is known to act as a physical barrier to tissue regeneration by blocking the way to axonal, vascular and neuronal infiltration. After the initial cell death in stroke, the activation and recruitment of microphage-like microglia allows for the clearance of debris in the lesion, leaving a compartmentalized cavity that can accept a large volume transplant without damaging further the surrounding healthy parenchyma. This stroke cavity is situated directly adjacent to the region of the brain that undergoes the most substantial repair and recovery, the peri-infarct tissue, meaning that any therapeutic delivered to the cavity will have direct access to the tissue target for repair and recovery.

In situ forming (injectable) hydrogel materials offer a unique platform to bioengineer pro-repair environments directly at the stroke site. Hydrogels can promote repair through providing structural support to the surrounding tissue to minimize secondary cell death and manage the inflammatory response. They can also effectively bypass the BBB by local injection of drug-loaded hydrogels, which can encourage cells from the surrounding parenchyma to infiltrate the scaffold and promote local regeneration. Injectable hydrogels can also serve as a cell transplantation vehicle to deliver NPCs. However, because access to the brain and the skull requires invasive delivery, the direct delivery of cells into the brain after stroke in conjunction with a pro-repair biomaterial must be controlled so that tissue adjacent to the infarct is not damaged [15]. Although in pre-clinical models the location of the stroke and the injection volume can be controlled such that hydrogel injections are possible without harmful effects, this will not be the case when translating to a clinical study. Therefore, hydrogels delivered intracerebrally must not swell significantly to avoid further brain damage, and injection would ideally be guided using a non-invasive imaging approach [20]. Modo et al. have successfully utilized MRI to simultaneously guide hydrogel injection and drain the brain to prevent intracranial pressure buildup [21].

4. Biomaterial-based targeted therapy to guide brain repair after stroke

Different tissue engineering approaches can be exploited to overcome the limitations of current therapies and promote the beneficial effects of endogenous post-stroke mechanisms.

4.1 Gel implantation to reduce post-stroke brain tissue inflammation

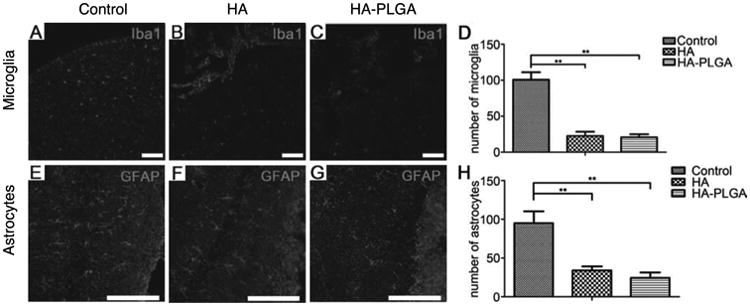

The first and most important step in the bioengineering of materials for brain repair after stroke is the development of a scaffold that contains the necessary mechanical [22-24], topographical, and integrin-binding features to allow, promote and guide cellular infiltration and axonal growth into a stroke cavity. One advantage of hydrogel biomaterials is that they show anti-inflammatory properties after inflammation if their mechanical properties match those of the surrounding tissue [25]. In situ formation of empty hyaluronic acid (HA)/peptide hydrogels directly at the stroke cavity showed differential macrophage activation depending on matrix stiffness; stiff hydrogels with a bulk storage modulus of 1300 Pa showed an increased macrophage density at the tissue-material interface compared to a softer gel [26]. This finding demonstrates the anti-inflammatory properties of materials that match the brain's tissue stiffness. Similarly, a functionalized self-assembling peptide hydrogel was shown to reduce the formation of the glial scar two weeks after stroke [27]. Hydrogels can then be loaded with anti-inflammatory drugs such as osteopondin to further limit inflammation. Gelatin microspheres loaded with osteopondin were injected into the striatum of stroked mice. Delivery from the microspheres showed longer lasting levels of osteopondin, decreased inflammation, and increased neuroprotection after stroke [28] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Fluorescent microscopy showing brain inflammation (reactive microglia, Iba1 - Ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 staining) and the astrocytic scar (GFAP - Glial Fibrillary Acid Protein staining) in a mouse stroked brain transplanted with HA and HA–PLGA (poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid), compared with a negative control brain with no implant. The results show a significantly reduced number of astrocytes and microglia in both transplanted groups compared with the control (**p < 0.01). Scale bar: 100 μm. Adapted with permission from [29].

4.2 Gel encapsulation of neural stem cell delivery and neuroprotection

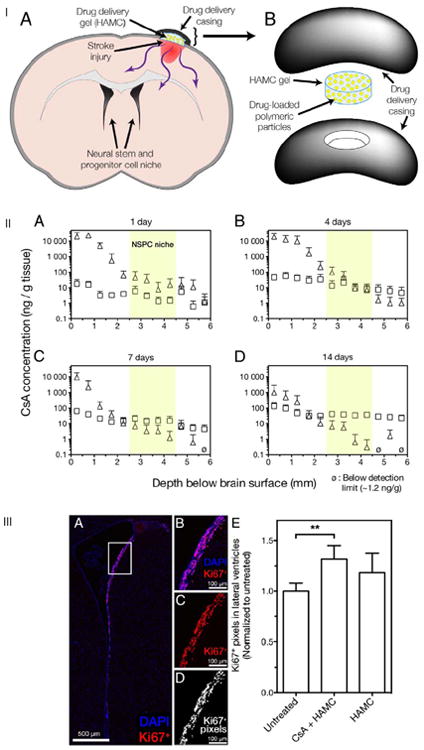

Engineering strategies that can further encourage the migration, survival and differentiation of NPCs by promoting a stem cell niche-like environment provides an avenue to rebuild a functional neuronal network. The Shoichet lab has engineered an injectable physically crosslinked hydrogel composed of a hyaluronan/methylcellulose (HAMC) blend. This hydrogel is applied epi-cortically through injection (Figure 3) and has been used to achieve sustained and sequential delivery of erythopoietin [30] [30,31], epidermal growth factor (EGF) [32] and most recently cyclosporine A (CsA) [33]. Encapsulated EGF released from this system increased NPC proliferation in uninjured and stroke-injured brains, while modifying EGF with polyethylene glycol (PEG) significantly enhanced protein stability, diffusion distance, and in vivo bioactivity. Encapsulated EPO release resulted in an attenuated inflammatory response, reduced stroke cavity size, and increased neurogenesis [31]. Sequential delivery of EGF-PEG and EPO by encapsulation of these factors in PLGA micro/nanoparticles and subsequent delivery within the hyaluronan/methyl cellulose (HAMC) blend reduced inflammation, significantly improved neurogenesis, and minimized tissue damage compared to intracerebroventricular infusion. CsA delivery showed increased drug concentration in the endogenous NPC niche compared to mini-pump delivery of the same drug especially at later time points [33]. These results indicate that local drug delivery from injectable hydrogel formulations can outperform traditional bolus delivery in the brain.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the injured-brain with the drug delivery HAMC scaffold device to achieve epi-cortical sustained local delivery to the brain (IA). Drug delivery system in expanded view shows that HAMC is held in place by both gelation and a casing comprised of polycarbonate discs (IB). CsA delivery from HAMC-PLGA composite (Δ) provides sustained release to the stroke injured rat brain. CsA systemically delivered with a subcutaneous while osmotic minipump (□) diffuses across the BBB into the brain at similar levels throughout the depths examined. CsA penetration and spatial distribution in the ipsilateral hemisphere was evaluated after for 1, 4, 7 and 14 days (IIA, B, C and D respectively) showing that CsA diffuses from HAMC to the NPC niche located 2.5 to 4.5 mm from the brain surface (IIA–D, highlighted in yellow). The epi-cortical delivery of CsA from HAMC increased the amount of Ki67+ proliferating cells in the lateral ventricles of stroke-injured rats. Representative images of Ki67, a marker for cell proliferation + staining of cells along the lateral ventricles (IIIA, IIIB) with (IIIC) and without a nucleus staining (Dapi). (IIID) The number of Ki67+ pixels along the dorsolateral ventricle wall was used to quantify the number of Ki67+ cells in both cerebral hemispheres (mean + standard deviation reported). Only treatment with CsA + HAMC significantly increased the Ki67+ signal in the ventricles (p = 0.006 vs. untreated). Adapted with permission from [33].

4.3 Tissue engineering strategies to enhance transplanted cell survival and engraftment

Materials to promote survival must be biocompatible but also bioresorbable to allow transplanted cells to degrade the biomaterials as they spread within the gel, form a network and migrate towards the peri-ischemic area where they can connect to an existing network. Indeed, NPCs transplanted within a commercially available HA/heparin/collagen hydrogel into the infarct cavity 7 days after stroke promoted the survival of NPCs and also diminished inflammatory infiltration of the graft [35]. Similarly, transplantation of NPCs within type I collagen scaffolds into the ischemic injury facilitated the structural recovery of the neural tissue and improved neurological function [36]. The same result was shown with NPCs encapsulated in a functionalized self-assembling peptide hydrogel [27].

4.4 Cell instructive biomaterials for the differentiation of transplanted cells

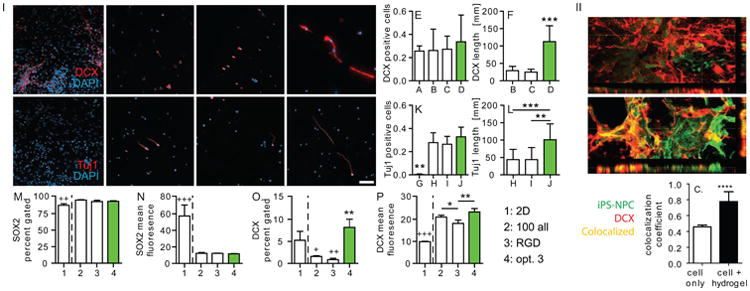

In addition to promoting transplanted cell survival, the delivery of NPCs within a hydrogel matrix provides the opportunity to guide transplanted cell differentiation. A powerful method to dictate cellular phenotype and differentiation is through the incorporation of ECM derived peptides such as the fibronectin-derived peptide RGD and the laminin-derived peptides IKVAV and YIGSR. These peptides are generally added at a 1:1:1 molar ratio. However, through using a design of experiments (DOE) multifactorial approach, we were able to optimize the outcome of NPC differentiation into immature neurons with an ECM-derived peptide ratio of 100 μM RGD:300 μM IKVAV:48 μM YIGSR [37] [38] (Figure 4). Furthermore, the overexpression of integrins via viral transduction has been shown to enhance the regenerative capacity of adult neurons [39]. NPC transplantation on VEGF-loaded PLGA microparticles to the stroke cavity showed increased NPC differentiation towards astrocytes and neurons and an enhanced revascularization of the stroke area [40].

Figure 4.

(I) iPS-NPCs cultured for 1 week in A) 2-D, and B–D) hydrogels were stained for Doublecortin (Dcx) and DAPI. The number of E) Dcx-positive cells and F) their axonal length was quantified. Cells were also stained and quantified for tuj1, a marker of mature neuron (G–J, K) and (L) their axonal length quantified. Flow cytometry data for M,N) SOX2, a marker of immature NPC and O,P) Dcx, indicate that the 3D HA hydrogels promote differentiation of the iPS-NPCs. *'s: difference between three dimensional samples. +'s: difference between 3D and 2D sample. Scale bar = 100 μm. */+: p < 0.5, **/++: p < 0.01, ***/+++: p < 0.001. (II) 3-dimensional reconstruction of (A) cell only and (B) cell + hydrogel sections stained for GFP-labeled transplanted cells and Dcx. (C) Colocalization analysis shows that the majority of Dcx positive signal seen in cell + hydrogel condition is from transplanted cell differentiation. Adapted from [38].

4.5 Nanotechnology-based VEGF delivery

As mentioned previously, both systemic and intracerebral bolus administration of VEGF have been unsuccessful and associated with severe side effects such as edema and hemorrhage. Interestingly, with either repeated administration or a hydrogel-mediated sustained release approach, VEGF local delivery consistently improved recovery and reduced the injury as compared to a bolus systemic administration strategy [16]. This demonstrated that a controlled release strategy of VEGF from a transplantable hydrogel may be a promising solution to overcome the main limitations of poor penetration across the BBB, the clinically unviable option of repeated local injections, and the short half-life of VEGF. One example of this strategy is the implantation of a composite non-injectable hyaluronic acid (HA) scaffold containing VEGF- and angiopoietin-1-loaded PLGA microparticles, and conjugated with an antibody against NOGO, an axonal growth inhibitor, resulting in improved vascularization and recovery by controlled release of the growth factors [29]. Our group recently demonstrated the sustained delivery of VEGF from an injectable HA gel containing RGD motifs and crosslinked with an MMP-sensitive crosslinker directly in the stroke cavity. VEGF was encapsulated within protease-labile, water-soluble nanocapsules formed through radical polymerization of acrylate-modified peptides (release rate is controlled through mixing L and D crosslinking peptides). We demonstrated that controlled release in vivo is associated with improved vascularization within the stroke peri-infarct and infarct regions [41].

Conclusions and future perspectives

Stroke is a traumatic event that is the most common cause of severe and long-term disability in adults. However, despite the widespread practice and proven benefits of reperfusion therapies, the majority of patients are still left with a long-lasting neurological impairment. Over the past few years, new therapeutic strategies aimed at enhancing endogenous repair mechanisms of the brain, such as post-stroke neurogenesis and angiogenesis, have failed in their translation to the clinic, mainly due to the short half-life and systemic effects of injected growth factors [2] and poor survival of transplanted cells. The lack of a successful medical therapy that promotes long-term recovery is a tremendous clinical and economic burden, urging the need to search for a medical solution outside the confines of conventional treatments practiced in neurology. Recent advances in tissue engineering have developed injectable biomaterials that can serve as a protective vehicle for both cells and trophic factors with distinct advantages compared with simple injection of either alone. The overall premise of in situ tissue regeneration is that by implanting an engineered scaffold at the site of injury or disease, one can generate a reparative niche that would lead to local tissue repair. Polymer-based hydrogels show numerous advantages as a wide variety of chemical, mechanical and spatial cues can be incorporated to adapt to the host tissue and to the encapsulated cells or bioactive signals.

Furthermore, although biomaterials-based regenerative medicine strategies have been studied for at least two decades, they have not been consistently applied to brain repair after stroke. Because of this, there are a number of already existing strategies that can be applied to the brain, such as incorporating an open pore structure and topographical cues and using hydrogel mechanics to guide differentiation. Although an open pore structure has been shown to be superior for tissue infiltration and repair in other organs [42,43] porous hydrogels have not been used for brain repair probably because these materials are typically non-injectable. However, two approaches to generate injectable porous hydrogels have been recently published [44,45]. Both manuscripts report superior tissue repair and reduced inflammation due to the porous nature of the hydrogel. In addition, topographical guidance cues have been extensively studied to guide spinal cord axonal sprouting [46], but have not been used to guide brain axonal sprouting. Thus, the introduction of porosity and topographical guidance cues offer exciting new possibilities for brain repair. In addition, mechanical guidance cues have been shown to be a powerful differentiation cue to neural progenitor cells [24]. The use of mechanics, however, has not been exploited in vivo to guide differentiation of transplanted or local progenitors, likely because soft matrices (needed to guide neuronal differentiation) tend to degrade faster than desired. Therefore, approaches to decouple matrix mechanical properties from matrix stability are needed to fully exploit mechanical guidance cues.

A number of new studies report on hydrogels that contain both physical and covalent bonds, which are soft and have long lasting mechanical support because the physical bonds can break and reform as the cells infiltrate [47-49]. Physical hydrogels with covalent stabilization were used as a stem cell transplantation vehicle to the stroke cavity and shown to promote stem cell survival and angiogenesis without the delivery of angiogenic factors [50]. Along with physical guidance the delivery of trophic factors maybe needed to further encourage axonal sprouting functional connections [53].

Research Highlights.

Stroke is the leading cause of adult disability

In situ forming hydrogels can be injected directly into the stroke cavity

In situ forming hydrogels can be used to construct pro-repair environments in the brain after stroke

Drug-loaded in situ forming hydrogels can be used to bypass the BBB for the delivery of drugs to the brain

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin RL, Lloyd HG, Cowan AI. The early events of oxygen and glucose deprivation: setting the scene for neuronal death? Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:251–257. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ST C. The 3 Rs of Stroke Biology: Radial, Relayed, and Regenerative. Neurotherapeutics. 2015 Nov 24; doi: 10.1007/s13311-015-0408-0. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tam RY, Fuehrmann T, Mitrousis N, Shoichet MS. Regenerative therapies for central nervous system diseases: a biomaterials approach. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:169–188. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dirnagl U, Iadecola C, Moskowitz MA. Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: an integrated view. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:391–397. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michalski D, Hartig W, Krueger M, Hobohm C, Kas JA, Fuhs T. A novel approach for mechanical tissue characterization indicates decreased elastic strength in brain areas affected by experimental thromboembolic stroke. Neuroreport. 2015;26:583–587. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sofroniew MV, Vinters HV. Astrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:7–35. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0619-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang L, Wu ZB, Zhuge Q, Zheng W, Shao B, Wang B, Sun F, Jin K. Glial scar formation occurs in the human brain after ischemic stroke. Int J Med Sci. 2014;11:344–348. doi: 10.7150/ijms.8140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alvarez-Buylla A, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Tramontin AD. A unified hypothesis on the lineage of neural stem cells. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:287–293. doi: 10.1038/35067582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krupinski J, Kaluza J, Kumar P, Kumar S, Wang JM. Role of angiogenesis in patients with cerebral ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1994;25:1794–1798. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.9.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slevin M, Krupinski J, Slowik A, Kumar P, Szczudlik A, Gaffney J. Serial measurement of vascular endothelial growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta1 in serum of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2000;31:1863–1870. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.8.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohab JJ, Fleming S, Blesch A, Carmichael ST. A neurovascular niche for neurogenesis after stroke. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006;26:13007–13016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4323-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen CJ, Ding D, Starke RM, Mehndiratta P, Crowley RW, Liu KC, Southerland AM, Worrall BB. Endovascular vs medical management of acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2015 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobkin BH, Dorsch A. New evidence for therapies in stroke rehabilitation. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15:331. doi: 10.1007/s11883-013-0331-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemmens R, Steinberg GK. Stem cell therapy for acute cerebral injury: what do we know and what will the future bring? Curr Opin Neurol. 2013;26:617–625. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma Y, Zechariah A, Qu Y, Hermann DM. Effects of vascular endothelial growth factor in ischemic stroke. J Neurosci Res. 2012;90:1873–1882. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woerly S, Marchand R, Lavallee C. Intracerebral implantation of synthetic polymer/biopolymer matrix: a new perspective for brain repair. Biomaterials. 1990;11:97–107. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(90)90123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woerly S, Laroche G, Marchand R, Pato J, Subr V, Ulbrich K. Intracerebral implantation of hydrogel-coupled adhesion peptides: tissue reaction. J Neural Transplant Plast. 1995;5:245–255. doi: 10.1155/NP.1994.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Overman JJ, Clarkson AN, Wanner IB, Overman WT, Eckstein I, Maguire JL, Dinov ID, Toga AW, Carmichael ST. A role for ephrin-A5 in axonal sprouting, recovery, and activity-dependent plasticity after stroke. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:E2230–2239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204386109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20*.Massensini AR, Ghuman H, Saldin LT, Medberry CJ, eane TJ, Nicholls FJ, Velankar SS, Badylak SF, Modo M. Concentration-dependent rheological properties of ECM hydrogel for intracerebral delivery to a stroke cavity. Acta Biomater. 2015;27:116–130. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.08.040. This article highlights the influence of the biomaterial stiffness, viscosity and elasticity on the material-host tissue interaction after transplantation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholls FJ, Rotz MW, Ghuman H, MacRenaris KW, Meade TJ, Modo M. DNA-gadolinium-gold nanoparticles for in vivo T1 MR imaging of transplanted human neural stem cells. Biomaterials. 2015;77:291–306. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sack I, Bernd B, Jens W, Dieter K, Uwe H, Sebastian P, Peter M, Jürgen B. The impact of aging and gender on brain viscoelasticity. NeuroImage. 2009;46:652–657. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.William JT. The mechanobiology of brain function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2012;13 doi: 10.1038/nrn3383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Penelope CG, William JM, David FM, Evelyn SS, Paul AJ. Matrices with Compliance Comparable to that of Brain Tissue Select Neuronal over Glial Growth in Mixed Cortical Cultures. Biophysical Journal. 2008;90 doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.073114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoban DB, Newland B, Moloney TC, Howard L, Pandit A, Dowd E. The reduction in immunogenicity of neurotrophin overexpressing stem cells after intra-striatal transplantation by encapsulation in an in situ gelling collagen hydrogel. Biomaterials. 2013;34:9420–9429. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26**.Lam J, Lowry WE, Carmichael ST, Segura T. Delivery of iPS-NPCs to the Stroke Cavity within a Hyaluronic Acid Matrix Promotes the Differentiation of Transplanted Cells. Advanced Functional Materials. 2014;24:7053–7062. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201401483. NPC transplantation using a hyaluronic acid/peptide in situ forming hydrogel was optimized to promote NPC survival during the injection and gellation process. Injection speed and needle gauge were found to be key factors regulating cell survival during transplantation. Transplanted NPC showed an increased neuronal differentiation when transplanted in the hyaluronic hydrogel compared to no hydrogel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27**.Cheng TY, Chen MH, Chang WH, Huang MY, Wang TW. Neural stem cells encapsulated in a functionalized self-assembling peptide hydrogel for brain tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2013;34:2005–2016. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.11.043. This article is an excellent example of how the addition of adhesive motifs in hydrogels can promote encapsulated neural progenirot cell survival and differentiation while reducing the peri-infarct scar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28**.Jin Y, Kim IY, Kim ID, Lee HK, Park JY, Han PL, Kim KK, Choi H, Lee JK. Biodegradable gelatin microspheres enhance the neuroprotective potency of osteopontin via quick and sustained release in the post-ischemic brain. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:3126–3135. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.02.045. This article provides an example of how engineered biodegradable microspheres can be utilized to protect encapsulated drugs from the inflammation-derived degradation after delivery in the injured brain. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29*.Ju R, Wen Y, Gou R, Wang Y, Xu Q. The experimental therapy on brain ischemia by improvement of local angiogenesis with tissue engineering in the mouse. Cell Transplant. 2014;23 Suppl 1:S83–95. doi: 10.3727/096368914X684998. Very innovative study targeting both post-stroke angiogenesis and axonal growth after stroke. The authors show a siginificant effect on recovery and vessel growth. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitaksuteepong T, Somsiri A, Waranuch N. Targeted transfollicular delivery of artocarpin extract from Artocarpus incisus by means of microparticles. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2007;67:639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, Cooke MJ, Morshead CM, Shoichet MS. Hydrogel delivery of erythropoietin to the brain for endogenous stem cell stimulation after stroke injury. Biomaterials. 2012;33:2681–2692. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32**.Wang Y, Cooke MJ, Sachewsky N, Morshead CM, Shoichet MS. Bioengineered sequential growth factor delivery stimulates brain tissue regeneration after stroke. J Control Release. 2013;172:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.07.032. This elegant work employs the use of PLGA and polymeric particles, each retaining a different growth factor, and both encapsulated within a hydrogel, to deliver sequentially the growth factors in a mouse injured brain after stroke. The authors show an improved tissue repair via reduced stroke-induced damage compared to the delivery of the same drugs via implanted pumps in the ventricle. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tuladhar A, Morshead CM, Shoichet MS. Circumventing the blood-brain barrier: Local delivery of cyclosporin A stimulates stem cells in stroke-injured rat brain. J Control Release. 2015;215:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uchimura E, Yamada S, Uebersax L, Yoshikawa T, Matsumoto K, Kishi M, Funeriu DP, Miyake M, Miyake J. On-chip transfection of PC12 cells based on the rational understanding of the role of ECM molecules: efficient, non-viral transfection of PC12 cells using collagen IV. Neuroscience Letters. 2005;378:40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhong J, Chan A, Morad L, Kornblum HI, Fan G, Carmichael ST. Hydrogel matrix to support stem cell survival after brain transplantation in stroke. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair. 2010;24:636–644. doi: 10.1177/1545968310361958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu H, Cao B, Feng M, Zhou Q, Sun X, Wu S, Jin S, Liu H, Lianhong J. Combinated transplantation of neural stem cells and collagen type I promote functional recovery after cerebral ischemia in rats. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2010;293:911–917. doi: 10.1002/ar.20941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herz J, Reitmeir R, Hagen SI, Reinboth BS, Guo Z, Zechariah A, ElAli A, Doeppner TR, Bacigaluppi M, Pluchino S, et al. Intracerebroventricularly delivered VEGF promotes contralesional corticorubral plasticity after focal cerebral ischemia via mechanisms involving anti-inflammatory actions. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45:1077–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38*.Lam J, Carmichael ST, Lowry WE, Segura T. Hydrogel design of experiments methodology to optimize hydrogel for iPSC-NPC culture. Adv Healthc Mater. 2015;4:534–539. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201400410. This manuscript utilizes design of experiments to systematically optimize the concentration of three ECM peptides, RGD, YIGSR and IKVAV on neuroprogenitor cell survival and differentiation. A non-equimolar concentration of each peptide was found to be optimal to promote progenitor cell survival. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andrews MR, Czvitkovich S, Dassie E, Vogelaar CF, Faissner A, Blits B, Gage FH, ffrench-Constant C, Fawcett JW. Alpha9 integrin promotes neurite outgrowth on tenascin-C and enhances sensory axon regeneration. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5546–5557. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0759-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bible E, Qutachi O, Chau DY, Alexander MR, Shakesheff KM, Modo M. Neo-vascularization of the stroke cavity by implantation of human neural stem cells on VEGF-releasing PLGA microparticles. Biomaterials. 2012;33:7435–7446. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.06.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41*.Zhu S, Nih L, Carmichael ST, Lu Y, Segura T. Enzyme-Responsive Delivery of Multiple Proteins with Spatiotemporal Control. Adv Mater. 2015;27:3620–3625. doi: 10.1002/adma.201500417. This study presents a successful drug sequential delivery strategy by using enzyme-responsive nanocapsules. The authors show that delivering VEGF and PEGF-BB respectively in an ischemic wound promotes tissue repair better than the administration of the growth factors alone or in the inverse order. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madden LR, Mortisen DJ, Sussman EM, Dupras SK, Fugate JA, Cuy JL, Hauch KD, Laflamme MA, Murry CE, Ratner BD. Proangiogenic scaffolds as functional templates for cardiac tissue engineering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:15211–15216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006442107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tokatlian T, Cam C, Segura T. Non-viral DNA delivery from porous hyaluronic acid hydrogels in mice. Biomaterials. 2014;35:825–835. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Griffin DR, Weaver WM, Scumpia PO, Di Carlo D, Segura T. Accelerated wound healing by injectable microporous gel scaffolds assembled from annealed building blocks. Nat Mater. 2015;14:737–744. doi: 10.1038/nmat4294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Drury JL, Mooney DJ. Hydrogels for tissue engineering: scaffold design variables and applications. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4337–4351. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khaing ZZ, Schmidt CE. Advances in natural biomaterials for nerve tissue repair. Neurosci Lett. 2012;519:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pakulska MM, Vulic K, Tam RY, Shoichet MS. Hybrid Crosslinked Methylcellulose Hydrogel: A Predictable and Tunable Platform for Local Drug Delivery. Adv Mater. 2015;27:5002–5008. doi: 10.1002/adma.201502767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McKinnon DD, Domaille DW, Brown TE, Kyburz KA, Kiyotake E, Cha JN, Anseth KS. Measuring cellular forces using bis-aliphatic hydrazone crosslinked stress-relaxing hydrogels. Soft Matter. 2014;10:9230–9236. doi: 10.1039/c4sm01365d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodell CB, MacArthur JW, Dorsey SM, Wade RJ, Woo YJ, Burdick JA. Shear-Thinning Supramolecular Hydrogels with Secondary Autonomous Covalent Crosslinking to Modulate Viscoelastic Properties. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25:636–644. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201403550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang J, Tokatlian T, Zhong J, Ng QK, Patterson M, Lowry B, Carmichael ST, Segura T. Physically Associated Synthetic Hydrogels with Long-Term Covalent Stabilization for Cell Culture and Stem Cell Transplantation. Advanced Materials. 2011 doi: 10.1002/adma.201103349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kleim JA, Chan S, Pringle E, Schallert K, Procaccio V, Jimenez R, Cramer SC. BDNF val66met polymorphism is associated with modified experience-dependent plasticity in human motor cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:735–737. doi: 10.1038/nn1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Partridge K, Yang X, Clarke NM, Okubo Y, Bessho K, Sebald W, Howdle SM, Shakesheff KM, Oreffo RO. Adenoviral BMP-2 gene transfer in mesenchymal stem cells: in vitro and in vivo bone formation on biodegradable polymer scaffolds. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;292:144–152. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loh NK, Woerly S, Bunt SM, Wilton SD, Harvey AR. The regrowth of axons within tissue defects in the CNS is promoted by implanted hydrogel matrices that contain BDNF and CNTF producing fibroblasts. Exp Neurol. 2001;170:72–84. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]