Abstract

Tumors are characterized by aberrant extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling and chronic inflammation. While advances in biomaterials and tissue engineering strategies have led to important new insights regarding the role of ECM composition, structure, and mechanical properties in cancer in general, the functional link between these parameters and macrophage phenotype is poorly understood. Nevertheless, increasing experimental evidence suggests that macrophage behavior is similarly controlled by physicochemical properties of the ECM and consequential changes in mechanosignaling. Here, we will summarize the current knowledge of macrophage biology and ECM-mediated differences in mechanotransduction and discuss future opportunities of biomaterials and tissue engineering platforms to interrogate the functional relationship between these parameters and their relevance to cancer.

Introduction

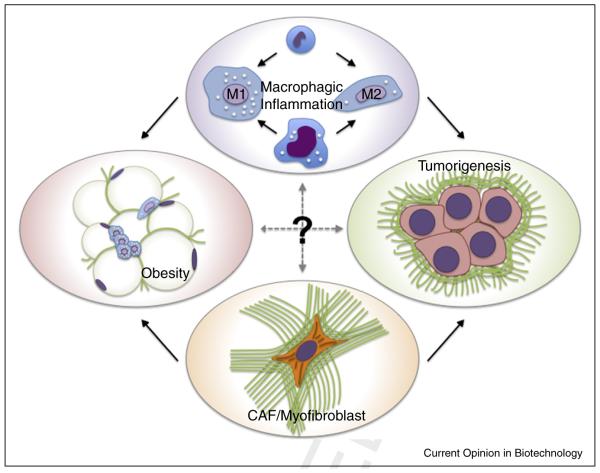

Fibrosis, also termed desmoplasia, and macrophagic inflammation represent two hallmark features of the tumor microenvironment that serve as prognostic indicators for poor clinical outcome [1,2]. Interestingly, both phenomena are also notably present in various other conditions epidemiologically linked to cancer (e.g. obesity, chronic liver disease), and increasing experimental evidence suggests that they contribute to tumor development and progression under these conditions [3,4]. Indeed, it is widely accepted that fibrosis and macrophages promote cancer independently [5,6], and their reciprocal actions propagate tissue dysfunction in other conditions such as obesity [4]. Nevertheless, the functional connections between fibrosis and macrophage functions and the resulting effect on tumorigenesis remain unclear (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Microenvironmental fibrosis and inflammation mediate cancer progression as well as tissue dysfunction in non neoplastic conditions such as obesity. The cellular mediators of fibrosis, activated fibroblasts (myofibroblasts or cancer activated fibroblasts), recruit macrophages by secreting pro inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and by depositing ECMs with varying composition, structure, and mechanics. Nevertheless, the role of obesity and cancer associated fibrotic ECMs in altering macrophage mechanosignaling and the relevance of these changes to tumorigenesis remain unclear.

Tumor-associated and obesity-associated fibrosis can be attributed to increased presence of activated fibroblasts, which mediate changes in extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition. Activated fibroblasts are typically referred to as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) or myofibroblasts and are characterized by excessive deposition of fibrillar ECM components including collagen type I and fibronectin. The inherent contractile phenotype of CAFs and myofibroblasts leads to alignment and partial unfolding of individual ECM fibrils that, in turn, enhances fiber thickness, stiffness, and exposure of cryptic binding domains [7–9]. Collectively, these compositional, structural, and mechanical changes of the ECM promote increased tissue density and stiffness, which is used in cancer patients to detect a mass via radiography and/or palpation. Elevated tissue stiffness additionally impacts tumorigenesis by directly perturbing epithelial morphogenesis, promoting local invasion and metastasis [10], and driving further activation of fibroblasts and other stromal cells through altered mechanosignaling [11].

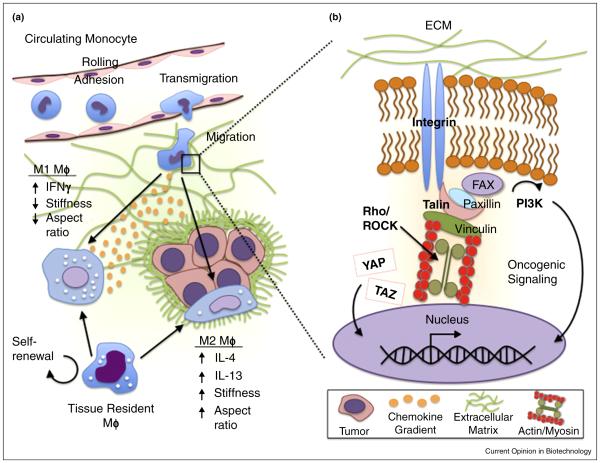

Mechanosignaling is the process in which altered physicochemical stimuli of the ECM are converted into biochemical signals to direct cellular behaviors (Figure 2b). Mechanotransduction pathways are activated by altered engagement of adhesion receptors (e.g. integrins and CD44) that leads to varied cytoskeletal tension and downstream signaling ultimately controlling many processes relevant to tumor initiation and progression including cell proliferation, migration, and apoptosis [12–14]. Notably, adhesion receptors can also cross-talk with growth factor and cytokine receptors by sharing similar downstream signal transduction networks and thus, altered ECM characteristics can additionally modify cell behavior indirectly. Nevertheless, the role of these signaling processes in guiding macrophage behavior in tumor-associated and chronically fibrotic ECM microenvironments is frequently overlooked.

Figure 2.

Mechanosignaling regulation of macrophage phenotype. (a) Macrophages (MΦ) derived from either the circulating monocyte pool or the tissue resident macrophage pool must adapt and respond to a variety of stresses and strains during their lifespan. Differentiation into either classically (M1) or alternatively activated (M2) macrophages is directed by chemokine and cytokine input, but also by varied mechanosignaling caused by changes in ECM stiffness and/or cell morphology. (b) Close up view of cell ECM interactions and mechanotransduction. Integrin attachment to ECM activates signal transduction via Rho GTPase mediated actin myosin contractility to direct cellular behaviors. Additional changes include stimulation of YAP/TAZ transcriptional regulators and downstream targets of phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3K) that regulate cell growth, FAK, focal adhesion kinase; ROCK, Rho associated protein kinase; YAP, yes associated protein; TAZ, transcriptional co activator with PDZ binding motif.

This review will explore current advances in tissue engineering and biomaterials to study the role of ECM physicochemical properties and mechanosignaling in macrophage behavior as it pertains to tumorigenesis. Breast cancer and obesity will be used as examples of tumor-associated and — permissive states linked to fibrosis and macrophagic inflammation, respectively. First, we will review current knowledge of ECM–macrophage interactions. Subsequently, we will discuss biomaterials-based model systems to study the role of ECM physicochemical properties in driving tumorigenic macrophage functions. Finally, we will identify future opportunities for tissue-engineered model systems to study the relationships of macrophages, the ECM, and mechanosignaling.

Macrophagic inflammation and fibrosis — partners in pathology

Macrophages are hematopoietic cells that have wide physiologic roles in the body ranging from innate immunity to trophic roles during health and disease [15]. Macrophages derive from either circulating monocyte or yolk sac-derived tissue resident pools and can be broadly classified into two phenotypes, referred to as polarization: (1) M1/classically activated macrophages that are pro-inflammatory in response to triggers like interferon gamma (IFNγ) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and (2) M2/alternatively activated macrophages which are anti-inflammatory, stimulated by the cytokines interleukin-4 and 13 (IL-4 and IL-13), and are involved in repair and remodeling of tissues (Figure 2a) [16]. Generally, M1 macrophages are considered tumoricidal whereas M2 macrophages are considered tumor promoting [17]. Hence, it is not surprising that tumor cells appear to educate the majority of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) to be biased toward an M2 phenotype [18].

During health, fibrosis and macrophagic inflammation are well-coordinated and self-limiting; for example, due to the resolution of mechanical [19] and biochemical stimuli upon completion of wound healing [20]. On the other hand, pathological fibrosis, as present in obese adipose tissue and the peritumoral microenvironment, is characterized by continued and unchecked pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory signaling [4,21]. This suggests that fibrosis and macrophages are functionally coupled and that ECM-mediated differences in mechanotransduction may play a role in this process. Indeed, fibrotic remodeling in obese adipose tissue correlates to macrophagic inflammation independently of body mass index [3] and increased stroma stiffness in clinical breast cancer samples positively correlates with the number of infiltrated TAMs, and this correlation is stronger in more aggressive tumor subtypes [22•].

While increasing experimental evidence suggests that ECM physicochemical properties directly affect macrophage polarization [23••,24], CAFs and myofibroblasts further potentiate this process by secreting soluble factors that modulate macrophage activation. For example, both cell types secrete CCL2, which stimulates macrophage recruitment and thus malignancy in both the tumor microenvironment and during obesity [25,26]. When combined, biochemical and mechanical stimuli can alter cell behavior in a manner that goes beyond their pure additive effects [27]. However, it remains to be tested whether such synergistic interactions may also apply to myofibroblast/CAF-derived biochemical and mechanical stimuli and their impact on the tumor-promoting effects of macrophages.

Relevance of mechanotransduction to macrophage phenotype

Although the mechanisms via which fibrotic/desmoplastic ECM remodeling may regulate macrophage polarization are not well understood, changes in mechanotransduction likely play a key role. Macrophages and their precursors are fully capable to adapt their behavior to a variety of compressive and shear stresses, strains, and tissue elasticities during tissue invasion (Figure 2a) [28]. Yet our knowledge of the cellular and molecular signals that may underlie differential macrophage responses to their mechanical environment is limited and currently mostly derived from extrapolating results obtained with other cell types (Figure 2b).

Studies with mesenchymal stem and tumor cells, for example, have revealed that ECM mechanical alterations mediate phenotypic changes by regulating integrin clustering, focal adhesion formation, and cell contractility in a manner that depends on Rho GTPase and Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) signaling [10,29]. Stiffness-dependent increases in cell contractility, in turn, cross-talk with growth factor receptor signaling and can up-regulate down-stream events such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling, an important participant in oncogenic transformation [30–32]. Furthermore, cellular interactions with stiffer ECM promote nuclear localization of transcriptional regulators of cell-proliferative and anti-apoptotic genes including Yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) [3,33,34]. As the self-renewing tissue resident macrophage pool can be recruited to become TAMs [35,36] or significantly contribute to obesity-associated macrophagic inflammation [37], these mechanosignaling pathways may play a role in the proliferation of this compartment.

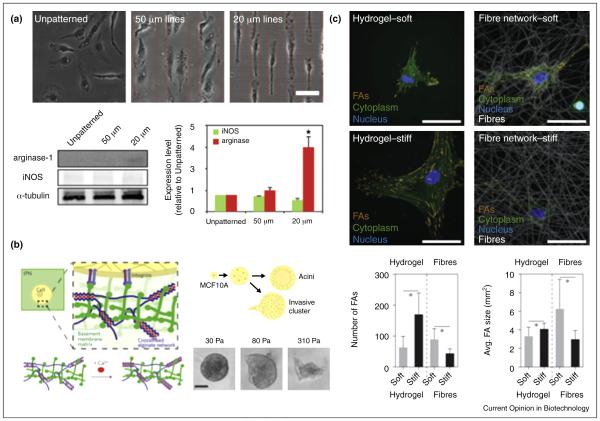

Although it has yet to be elucidated whether macrophages are regulated through similar mechanisms, compelling evidence indicates that their phenotype is dependent on substrate stiffness. In fact, increased substrate rigidity decreases macrophage pro-inflammatory responses directly [38,39] but may also indirectly affect macrophages by modulating cell shape [40•]. Forcing macrophages into an elongated shape with micropatterned arrays of fibronectin upregulates M2 markers and decreases response to pro-inflammatory stimuli (Figure 3a) [40•]. These findings are further supported by the finding that ROCK represents a master switch in macrophage polarization with ROCK2 inhibition promoting M1 while decreasing M2 markers [41]. Finally, ECM stiffness-dependent changes in cell contractility can stimulate paracrine signaling of macrophage-modulating morphogens; for example, by enhancing mechanoactivation of transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) [42], a potent immunosuppressive cytokine that modulates macrophages to a more M2 phenotype and reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion [43].

Figure 3.

Examples of biomaterials systems for studying macrophage phenotypic changes in response to fibrotic ECMs. (a) Geometric control of murine bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) by micropatterning drives macrophage polarization to an M2 phenotype with cellular elongation [40•] suggesting that microenvironmental control of cell shape influences macrophage function. (b) Interpenetrating network of calcium crosslinked alginate in Matrigel® to control hydrogel stiffness independent of ligand binding density and porosity revealed that stiffness alone induces an invasive phenotype in MCF10A breast epithelial cells [31••]. (c) Studies comparing cellular stiffness responses on flat hydrogels and synthetic fibrous materials revealed that they were inversely correlated. Unlike 2D hydrogels where greater bulk stiffness increased focal adhesion formation and proliferation, greater stiffness of individual fibers limited the ability of human mesenchymal stem cell (hMSC) to bundle fibers and form focal adhesion complexes [55].

Source: Images were reproduced with permission from the National Academy of Sciences (a) and Nature Publishing Group (b, c).

Biomaterials systems for studying fibrosis-associated macrophage mechanosignaling

Macrophages have typically been studied in monolayer culture or in vivo models. While two-dimensional (2D) cultures have led to important new insights, they cannot recapitulate the ECM compositional, structural, and mechanical changes that regulate macrophages during fibrosis. Mouse models on the other hand may not fully mimic human disease and isolated control of select parameters is difficult. We have previously shown that tissue engineered-model systems using biomaterials mimics of the ECM bridge the gap between 2D cultures and in vivo conditions [44,45] and thus offer potential to study macrophage behavior with fibrosis.

Natural biomaterials

Given their intrinsic biochemical and physical similarity to the native ECM, decellularized ECMs prepared by detergent-based extraction offer promise to study macrophages [46]. They can be prepared from cells or tissues prone to increased fibrotic remodeling [3] and are suitable to study macrophage responses to ECM-dependent changes in mechanosignaling or TGFβ1 mechanoactivation. However, decellularized ECMs frequently vary between batches, are difficult to scale up for higher throughput applications, and are mostly prepared from 2D cultures with their inherent limitations. Moreover, these ECMs are typically fragile during handling although improved protocols permit to prepare them more robustly by covalent coupling to their underlying sub-strates [47•]. Controlling functional properties of these ECMs selectively and across multiple time and length scales is still difficult, and due to the limited thickness of such substrates re-seeded cells may respond to the underlying culture plate rather than the ECM itself [48]. Matrigel® and collagen type I-based hydrogels are utilized to circumvent some of these limitations.

Matrigel® is a basement membrane mixture isolated from a mouse sarcoma whose composition varies widely between batches and does not permit mimicry of fibrosis-relevant ECM structural motifs and stiffnesses. The latter can be overcome by mixing Matrigel® with alginate to form interpenetrating networks whose stiffness can be adjusted through calcium-crosslinks (Figure 3b) [31••]. While this approach maintains constant adhesion ligand density and mimics physiologically more relevant visco-elastic rather than elastic matrix properties [49], it does not exclude an additional confounding factor of Matrigel®, namely that it contains growth factors that can interfere with macrophage phenotype. Collagen type I is devoid of growth factors, but stiffness adjustment is typically achieved by varying concentration, which independently alters cell behavior. Covalent crosslinking via non-enzymatic glycation overcomes this limitation [50], but simultaneously affects hydrogel pore size and thus possibly macrophage behavior [51,52]. Importantly, the source of collagen is important as bovine versus rat tailderived collagen forms gels with thicker fibers, larger pore sizes, and higher elastic modulus [53]. Thicker or stretched ECM fibrils are typically stiffer than thinner or unstretched fibers [54,55••], which may impact mechanosignaling at the fibril rather than bulk level (Figure 3c). The resulting functional consequences can be tested by altering collagen fibril characteristics independent of bulk stiffness; for example, by adjusting the gelation temperature or pH [53,56]. While both Matrigel and collagen type I offer many advantages including their remodelability by cells and ready adaptability across disciplines, their mechanical range is limited and spatiotemporal control of ECM properties is difficult.

Synthetic biomaterials

Synthetic biomaterials such as polyacrylamide (PA) or poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogels allow for more controlled modulation of ECM physicochemical parameters. While PA and PEG hydrogels are inherently non-adhesive, they can be functionalized to enable cell binding by coupling purified ECM components, decellularized ECM, or peptide sequences thereof [57]. For example, PA hydrogels modified with fibronectin or RGD adhesion peptides and adjusted in their cross-linking density through altering the ratio of acrylamide to bisacrylamide are routinely used to analyze stiffness-dependent cell responses [58]. However, PA cannot be remodeled by cells nor can cells be encapsulated into these gels due to monomer toxicity limiting these studies to 2D formats. PEG-based hydrogels circumvent the dimensionality and toxicity shortcomings, but cannot be remodeled by cells either. Introducing and/or removing functionalities (e.g. integrin adhesion sites and matrix metalloproteinase [MMP]-cleavable sequences) through light-dependent mechanisms (e.g. photoinitiated addition, photocrosslinking, or photodegradation [59,61,62••])]) or via modular bioclick and bioclip reactions can help to address this shortcoming. Selectively adding or removing functionality at a desired timepoint [63,64] or in a specific location [60,61] additionally provides the opportunity to introduce temporal and spatial control over both chemical and mechanical properties of the respective hydrogel. Despite their advantages, these model systems are often amorphous and lack ECM structural entities that drive macrophage behavior.

To mimic the combination of amorphous and fibrillar components in the native ECM, fibers prepared through electrospinning or polymerization of native ECM components could be integrated into composite hydrogels [65]. In particular, incorporation of fibers into hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels of varying bulk stiffness [66] will be exciting as hyaluronic acid is increased with fibrosis and cancer [67,68] and has been shown to modulate macrophage behavior [23,69]. Integrating varyingly stiff and thick fibers [55••] into hydrogels of altered bulk mechanical properties will permit to decouple the effects of individual fiber versus bulk stiffness properties on macrophages. Differentiating between these properties will be critical as most current research focuses on bulk mechanical properties, but disregards that fiber mechanics are similarly important and may, in fact, lead to differential cell responses [55••]. Finally, being able to modulate the orientation of such fibers, for example, by unidirectional compression of the fiber-containing hydrogels [70] will enable new insights. This manipulation will allow assessing whether changes in collagen fiber orientation from parallel to radial alignment upon tumor progression can influence macrophage migration [71].

Conclusions and perspectives

While the above described biomaterials strategies allow for multicomponent analysis of macrophage function in response to fibrosis-associated ECMs, these systems are coupled to ever evolving complexity and thus future opportunities. For example, computational strategies may become necessary to analyze the large multifaceted data sets and distinguish individual influences on cell behavior in a dynamic network of exponentially increasing interactions. Studying macrophage behavior in 3D tissue-engineered models furthermore requires high resolution imaging modalities for real-time tracking of cells and subcellular-components, which may not be routinely accessible by many labs. Moreover, it has to be kept in mind that incorporation of macrophages will alter the physicochemical properties of the utilized ECM mimics over time. Assessing the spatiotemporal feedback of macrophage phenotype and ECM compositional, structural, and mechanical properties will be necessary to advance our knowledge of the underlying mechanisms. In addition to evaluating the influence of ECM-mediated stress and strain on immune cells, biomaterials models should reflect the multicellular composition of fibrosis-associated microenvironment. For example, fibrosis is characterized by altered vasculature and thus altered convective and diffusive transport properties. Microfluidic co-culture devices with integrated vascular networks could be used to evaluate the role of transport properties as well as shear and interstitial pressure on processes essential to macrophage function [72,73]. Ultimately, these model systems should be extended to investigate the physical control of other immune cells that play important regulatory roles in fibrosis and/or tumor-associated microenvironments (e.g. T helper cells). In summary, the rapid development of new biomaterials and tissue engineering strategies provides an opportunity to further our understanding of macrophage interactions with fibrotic ECM microenvironments and their relevance to tumorigenesis. Ultimately, this offers the potential to identify new targets for future preventative or therapeutic interventions in order to positively impact the lives of individuals at risk for or living with cancer.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute through award numbers R01CA185293 and U54CA143876 (Cornell Center on the Microenvironment & Metastasis). Dr. Springer was supported by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health, under award number T32OD0011000.

References and recommended reading

References and recommended reading Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Mujtaba SS, Ni Y-B, Tsang JYS, Chan S-K, Yamaguchi R, Tanaka M, Tan P-H, Tse GM. Fibrotic focus in breast carcinomas: relationship with prognostic parameters and biomarkers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2842–2849. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2955-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Cheng S, Zhang M, Zhen L, Pang D, Zhang Q, Li Z. High-infiltration of tumor-associated macrophages predicts unfavorable clinical outcome for node negative breast cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seo BR, Bhardwaj P, Choi S, Gonzalez J, Eguiluz RCA, Wang K, Mohanan S, Morris PG, Du B, Zhou XK, et al. Obesity-dependent changes in interstitial ECM mechanics promote breast tumorigenesis. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:1–12. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun K, Tordjman J, Clément K, Scherer PE. Fibrosis and adipose tissue dysfunction. Cell Metab. 2013;18:470–477. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pickup MW, Mouw JK, Weaver VM. The extracellular matrix modulates the hallmarks of cancer. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:1243–1253. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sica A, Schioppa T, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages are a distinct M2 polarised population promoting tumour progression: potential targets of anti-cancer therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:717–727. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonnans C, Chou J, Werb Z. Remodelling the extracellular matrix in development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:786–801. doi: 10.1038/nrm3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krammer A, Craig D, Thomas WE, Schulten K, Vogel V. A structural model for force regulated integrin binding to fibronectin’s RGD-synergy site. Matrix Biol. 2002;21:139–147. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klotzsch E, Smith ML, Kubow KE, Muntwyler S, Little WC, Beyeler F, Gourdon D, Nelson BJ, Vogel V. Fibronectin forms the most extensible biological fibers displaying switchable force-exposed cryptic binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:18267–18272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907518106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, Lakins JN, Rozenberg GI, Gefen A, Reinhart-King CA, Margulies SS, Dembo M, Boettiger D, et al. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu F, Mih JD, Shea BS, Kho AT, Sharif AS, Tager AM, Tschumperlin DJ. Feedback amplification of fibrosis through matrix stiffening and COX-2 suppression. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:693–706. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Multhaupt HAB, Leitinger B, Gullberg D, Couchman JR. Extracellular matrix component signaling in cancer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.10.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2015.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Parekh A, Weaver AM. Regulation of invadopodia by mechanical signaling. Exp. Cell Res. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.10.038. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.10.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Yu F-X, Zhao B, Guan K-L. Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue homeostasis, and cancer. Cell. 2015;163:811–828. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollard JW. Trophic macrophages in development and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:259–270. doi: 10.1038/nri2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olefsky JM, Glass CK. Macrophages, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:219–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coffelt SB, Lewis CE, Naldini L, Brown JM, Ferrara N, De Palma M. Elusive identities and overlapping phenotypes of proangiogenic myeloid cells in tumors. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:1564–1576. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sousa S, Brion R, Lintunen M, Kronqvist P, Sandholm J, Mönkkönen J, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P-L, Lauttia S, Tynninen O, Joensuu H, et al. Human breast cancer cells educate macrophages toward the M2 activation status. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:101. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0621-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Galli A, Bochaton-Piallat M-L, Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast: one function, multiple origins. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1807–1816. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Headland SE, Norling LV. The resolution of inflammation: principles and challenges. Semin Immunol. 2015;27:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dvorak HF. Tumors: wounds that do not heal. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1650–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612253152606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Acerbi I, Cassereau L, Dean I, Shi Q, Au A, Park C, Chen YY, Liphardt J, Hwang ES, Weaver VM. Human breast cancer invasion and aggression correlates with ECM stiffening and immune cell infiltration. Integr Biol. 2015;7:1120–1134. doi: 10.1039/c5ib00040h. This study illustrates the clinical significance of the integrated effects of tumor stromal fibrosis and macrophage infiltration in breast cancer progression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng FW, Slivka PF, Dearth CL, Badylak SF. Solubilized extracellular matrix from brain and urinary bladder elicits distinct functional and phenotypic responses in macrophages. Biomaterials. 2015;46:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.12.044. Solublized ECM from embryologically distinct tissues induce divergent macrophage polarization states due to differences in ECM composition. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han TTY, Toutounji S, Amsden BG, Flynn LE. Adipose-derived stromal cells mediate in vivo adipogenesis, angiogenesis and inflammation in decellularized adipose tissue bioscaffolds. Biomaterials. 2015;72:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitamura T, Qian B-Z, Soong D, Cassetta L, Noy R, Sugano G, Kato Y, Li J, Pollard JW. CCL2-induced chemokine cascade promotes breast cancer metastasis by enhancing retention of metastasis-associated macrophages. J Exp Med. 2015;212:1043–1059. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arendt LM, McCready J, Keller PJ, Baker DD, Naber SP, Seewaldt V, Kuperwasser C. Obesity promotes breast cancer by CCL2-mediated macrophage recruitment and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:6080–6093. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chandler EM, Seo BR, Califano JP, Andresen Eguiluz RC, Lee JS, Yoon CJ, Tims DT, Wang JX, Cheng L, Mohanan S, et al. Implanted adipose progenitor cells as physicochemical regulators of breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:9786–9791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121160109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Previtera ML. Mechanotransduction in the immune system. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2014;7:473–481. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wen JH, Vincent LG, Fuhrmann A, Choi YS, Hribar KC, Taylor-Weiner H, Chen S, Engler AJ. Interplay of matrix stiffness and protein tethering in stem cell differentiation. Nat Mater. 2014;13:979–987. doi: 10.1038/nmat4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang H, Tibbitt MW, Langer SJ, Leinwand LA, Anseth KS. Hydrogels preserve native phenotypes of valvular fibroblasts through an elasticity-regulated PI3K/AKT pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:19336–19341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306369110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaudhuri O, Koshy ST, Branco da Cunha C, Shin J-W, Verbeke CS, Allison KH, Mooney DJ. Extracellular matrix stiffness and composition jointly regulate the induction of malignant phenotypes in mammary epithelium. Nat Mater. 2014;13:970–978. doi: 10.1038/nmat4009. This study showed that interpenetrating networks of calcium-crosslinked alginate and reconstituted basement membrane allow tuning hydrogel stiffness independently of composition with effects on tumor cell mechanosignaling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubashkin MG, Cassereau L, Bainer R, DuFort CC, Yui Y, Ou G, Paszek MJ, Davidson MW, Chen Y-Y, Weaver VM. Force engages vinculin and promotes tumor progression by enhancing PI3K activation of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-triphosphate. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4597–4611. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aragona M, Panciera T, Manfrin A, Giulitti S, Michielin F, Elvassore N, Dupont S, Piccolo S. A mechanical checkpoint controls multicellular growth through YAP/TAZ regulation by actin-processing factors. Cell. 2013;154:1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang Y, Rowe RG, Botvinick E, Kurup A, Putnam A, Seiki M, Weaver V, Keller E, Goldstein S, Dai J, et al. MT1-MMP-dependent control of skeletal stem cell commitment via a β1-Integrin/YAP/TAZ signaling axis. Dev Cell. 2013;25:402–416. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franklin RA, Liao W, Sarkar A, Kim MV, Bivona MR, Liu K, Pamer EG, Li MO. The cellular and molecular origin of tumor-associated macrophages. Science. 2014;344:921–925. doi: 10.1126/science.1252510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lahmar Q, Keirsse J, Laoui D, Movahedi K, Van Overmeire E, Van Ginderachter JA. Tissue-resident versus monocyte-derived macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Biochim Biophys Acta - Rev Cancer. 2016;1865:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amano SU, Cohen JL, Vangala P, Tencerova M, Nicoloro SM, Yawe JC, Shen Y, Czech MP, Aouadi M. Local proliferation of macrophages contributes to obesity-associated adipose tissue inflammation. Cell Metab. 2014;19:162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel NR, Bole M, Chen C, Hardin CC, Kho AT, Mih J, Deng L, Butler J, Tschumperlin D, Fredberg JJ, et al. Cell elasticity determines macrophage function. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blakney AK, Swartzlander MD, Bryant SJ. The effects of substrate stiffness on the in vitro activation of macrophages and in vivo host response to poly(ethylene glycol)-based hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res. 2012;100A:1375–1386. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McWhorter FY, Wang T, Nguyen P, Chung T, Liu WF. Modulation of macrophage phenotype by cell shape. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:17253–17258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308887110. Using micropatterned substrates prepared by soft lithography this study shows that the polarization state of macrophages depends on cell shape. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zandi S, Nakao S, Chun K-H, Fiorina P, Sun D, Arita R, Zhao M, Kim E, Schueller O, Campbell S, et al. ROCK isoform specific polarization of macrophages associated with age-related macular degeneration. Cell Rep. 2015;10:1173–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klingberg F, Chow ML, Koehler A, Boo S, Buscemi L, Quinn TM, Costell M, Alman BA, Genot E, Hinz B. Prestress in the extracellular matrix sensitizes latent TGF-B1 for activation. J Cell Biol. 2014;207:283–297. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201402006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferrante CJ, Leibovich SJ. Regulation of macrophage polarization and wound healing. Adv Wound Care. 2012;1:10–16. doi: 10.1089/wound.2011.0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fischbach C, Chen R, Matsumoto T, Schmelzle T, Brugge JS, Polverini PJ, Mooney DJ. Engineering tumors with 3D scaffolds. Nat Methods. 2007;4:855–860. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DelNero P, Lane M, Verbridge SS, Kwee B, Kermani P, Hempstead B, Stroock A, Fischbach C. 3D culture broadly regulates tumor cell hypoxia response and angiogenesis via pro-inflammatory pathways. Biomaterials. 2015;55:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Badylak SF. Decellularized allogeneic and xenogenic tissue as a bioscaffold for regenerative medicine: factors that influence the host response. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014;42:1517–1527. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0963-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prewitz MC, Seib FP, von Bonin M, Friedrichs J, Stißel A, Niehage C, Müller K, Anastassiadis K, Waskow C, Hoflack B, et al. Tightly anchored tissue-mimetic matrices as instructive stem cell microenvironments. Nat Methods. 2013;10:788–794. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2523. Fibronectin covalently bound to a glass surface provides an anchor for realistic ECM assembly by tissue specific progenitor cells, stabilizes these matrices during decellularization, and enables subsequent studies of stem cell responses. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buxboim A, Ivanovska IL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity, cytoskeletal forces and physics of the nucleus: how deeply do cells “feel” outside and in? J Cell Sci. 2010;123:297–308. doi: 10.1242/jcs.041186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chaudhuri O, Gu L, Darnell M, Klumpers D, Bencherif SA, Weaver JC, Huebsch N, Mooney DJ. Substrate stress relaxation regulates cell spreading. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6365. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Girton T, Oegema T, Tranquillo R. Exploiting glycation to stiffen and strengthen tissue equivalents for tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;46:87–92. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199907)46:1<87::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Goethem E, Poincloux R, Gauffre F, Maridonneau-Parini I, Le Cabec V. Matrix architecture dictates three-dimensional migration modes of human macrophages: differential involvement of proteases and podosome-like structures. J Immunol. 2010;184:1049–1061. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trappmann B, Gautrot JE, Connelly JT, Strange DGT, Li Y, Oyen ML, Cohen Stuart MA, Boehm H, Li B, Vogel V, et al. Extracellular-matrix tethering regulates stem-cell fate. Nat Mater. 2012;11:742–742. doi: 10.1038/nmat3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wolf K, te Lindert M, Krause M, Alexander S, te Riet J, Willis AL, Hoffman RM, Figdor CG, Weiss SJ, Friedl P. Physical limits of cell migration: control by ECM space and nuclear deformation and tuning by proteolysis and traction force. J Cell Biol. 2013;201:1069–1084. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201210152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kubow KE, Klotzsch E, Smith ML, Gourdon D, Little WC, Vogel V. Crosslinking of cell-derived 3D scaffolds up-regulates the stretching and unfolding of new extracellular matrix assembled by reseeded cells. Integr Biol (Camb) 2009;1:635–648. doi: 10.1039/b914996a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baker BM, Trappmann B, Wang WY, Sakar MS, Kim IL, Shenoy VB, Burdick JA, Chen CS. Cell-mediated fibre recruitment drives extracellular matrix mechanosensing in engineered fibrillar microenvironments. Nat Mater. 2015;14:1262–1268. doi: 10.1038/nmat4444. Using flat hydrogels and synthetic matrices with controlled fiber proper ties this study suggests that fiber properties can regulate cell behavior independent of bulk stiffness. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moraes C, Sun Y, Simmons CA. (Micro)managing the mechanical microenvironment. Integr Biol (Camb) 2011;3:959–971. doi: 10.1039/c1ib00056j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Young DA, Choi YS, Engler AJ, Christman KL. Stimulation of adipogenesis of adult adipose-derived stem cells using substrates that mimic the stiffness of adipose tissue. Biomaterials. 2013;34:8581–8588. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.07.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pelham RJ, Jr, Yu-Li W. Cell locomotion and focal adhesions are regulated by substrate flexibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:13661–13665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khetan S, Guvendiren M, Legant WR, Cohen DM, Chen CS, Burdick JA. Degradation-mediated cellular traction directs stem cell fate in covalently crosslinked three-dimensional hydrogels. Nat Mater. 2013;12:458–465. doi: 10.1038/nmat3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kloxin AM, Tibbitt MW, Anseth KS. Synthesis of photodegradable hydrogels as dynamically tunable cell culture platforms. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1867–1887. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Owen SC, Fisher SA, Tam RY, Nimmo CM, Shoichet MS. Hyaluronic acid click hydrogels emulate the extracellular matrix. Langmuir. 2013;29:7393–7400. doi: 10.1021/la305000w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang C, Tibbitt MW, Basta L, Anseth KS. Mechanical memory and dosing influence stem cell fate. Nat Mater. 2014;13:645–652. doi: 10.1038/nmat3889. Photodegradable PEG hydrogels were used to decrease stiffness over time to monitor the mechanical memory of mesenchymal stem cells and how this retention of mechanical information alters cellular differentiation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patterson J, Hubbell JA. Enhanced proteolytic degradation of molecularly engineered PEG hydrogels in response to MMP-1 and MMP-2. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7836–7845. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chwalek K, Tsurkan MV, Freudenberg U, Werner C. Glycosaminoglycan-based hydrogels to modulate heterocellular communication in in vitro angiogenesis models. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4414. doi: 10.1038/srep04414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Highley CB, Rodell CB, Kim IL, Wade RJ, Burdick JA. Ordered, adherent layers of nanofibers enabled by supramolecular interactions. J Mater Chem B Mater Biol Med. 2014;2:8110–8115. doi: 10.1039/C4TB00724G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shen Y, Abaci HE, Krupsi Y, Weng L, Burdick JA, Gerecht S. Hyaluronic acid hydrogel stiffness and oxygen tension affect cancer cell fate and endothelial sprouting. Biomater Sci. 2014;2:655–665. doi: 10.1039/C3BM60274E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kang L, Lantier L, Kennedy A, Bonner JS, Mayes WH, Bracy DP, Bookbinder LH, Hasty AH, Thompson CB, Wasserman DH. Hyaluronan accumulates with high-fat feeding and contributes to insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2013;62:1888–1896. doi: 10.2337/db12-1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schwertfeger KL, Cowman MK, Telmer PG, Turley EA, McCarthy JB. Hyaluronan, inflammation, and breast cancer progression. Front Immunol. 2015;6:236. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rayahin JE, Buhrman JS, Zhang Y, Koh TJ, Gemeinhart RA. High and low molecular weight hyaluronic acid differentially influence macrophage activation. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2015;1:481–493. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brownfield DG, Venugopalan G, Lo A, Mori H, Tanner K, Fletcher DA. Bissell MJ: Patterned collagen fibers orient branching mammary epithelium through distinct signaling modules. Curr Biol. 2013;23:703–709. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Provenzano PP, Eliceiri KW, Campbell JM, Inman DR, White JG, Keely PJ. Collagen reorganization at the tumor-stromal interface facilitates local invasion. BMC Med. 2006;4:38. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-4-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morgan JP, Delnero PF, Zheng Y, Verbridge SS, Chen J, Craven M, Choi NW, Diaz Santana A, Kermani P, Hempstead B, et al. Formation of microvascular networks in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1820–1836. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miller JS, Stevens KR, Yang MT, Baker BM, Nguyen D-HT, Cohen DM, Toro E, Chen AA, Galie PA, Yu X, et al. Rapid casting of patterned vascular networks for perfusable engineered three-dimensional tissues. Nat Mater. 2012;11:768–774. doi: 10.1038/nmat3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]