Highlights

-

•

Gallstone obstruction is a rare clinical entity presenting usually in elderly patients and is associated with a medical history of biliary symptoms.

-

•

CT examination uncovered all findings consisting Rigler’s triad, thus air in the gall bladder, bowel obstruction and a gallstone inside the bowel lumen. It also identified a cholecystoduodenal fistula.

-

•

Rupture of the small bowel occurred intraoperatively, and a large 3.2 cm gallstone was located in the terminal ileum, which was recovered.

-

•

Post-surgical recovery was uneventful with no further report of obstruction symptoms at 6 month follow up.

Keywords: Gallstone bowel obstruction, Gallstone ileus, Rigler’s triad, Biliogastric fistula, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Gallstone bowel obstruction is a rare form of mechanical ileus usually presenting in elderly patients, and is associated with chronic or acute cholecystitis episodes.

Case presentation

We present the case of an 80 year old female with abdominal pain, inability to defecate and recurrent episodes of diarrhea for the past 8 months. CT examination uncovered a cholecystoduodenal fistula along with gas in the gall bladder and the presence of a ≥2 cm gallstone inside the small bowel lumen causing obstruction. Patient was admitted to the operating room, where a 3.2 cm gallstone was located in the terminal ileus. A rupture was found in the antimesenteric part of a discolored small bowel segment, approximately 60 cm from the ileocaecal valve, through which the gallstone was recovered. The bowel regained its peristalsis, and the rupture was debrided and sutured. Patient was discharged uneventfully on the 6th postoperative day.

Discussion

Gallstone ileus is caused due to the impaction of a gallstone inside the bowel lumen. It usually passes through a fistula connecting the gallstone with the gastrointestinal tract. It can present with nonspecific or acute abdominal symptoms. CT usually confirms the diagnosis, while there are a number of treatment options; conservative, minimal invasive and surgical. Our patient was successfully relieved of the obstruction through recovery of the gallstone using open surgery, with no repair of the fistula.

Conclussion

Although rare, gallstones must be suspected as a possible cause of bowel obstruction, especially in elderly patients reporting biliary symptoms.

1. Introduction

Gallstone ileus, or gallstone gastrointestinal obstruction, is a rare form of bowel obstruction caused by the presence of a gallstone in the bowel lumen, due to a fistula that connects the gallbladder with the gastrointestinal tract. It often presents in elderly people above the age of 65, and is related with a history of gallstones and recurrent episodes of cholecystitis. Differential diagnosis can be hard, due to nonspecific findings during physical examination, while there are a number of options regarding diagnosis and treatment. We present the rare case of an 80 year old female patient with gastrointestinal obstruction due to a 3.2 cm gallstone, which caused perforation of the small bowel wall. The aim of this report is to remind clinicians of this rare entity along with a review of the current literature.

2. Case presentation

An 80 year old Caucasian female was admitted to our emergencies department, complaining of vague periomphalic abdominal pain for the past 3 days, combined with an inability to defecate. Her past medical history included a partially controlled diabetes mellitus, hypertension and a pacemaker implantation due to bradycardia. She also reported recurrent episodes of diarrhea for the past 8 months. On physical examination, blood pressure was 138/74 mmHg, heart rate was 87 beats/min and body temperature was37.3C. Her abdomen was soft without tenderness but distended, which caused her heavy breathing.

Laboratory data revealed a white blood cell count of 9.6 × 103/μL, hemoglobin of 10.2 g/dL and a hematocrit of 30.7%. Biochemistry exams and liver function studies disclosed potassium 3.8 mmol/L, sodium 138 mmol/L, urea 27 mg/dl, creatinine 0.7 mg/dl, glucose 262 mg/dl, AST 13 IU/L, ALT 9 IU/L, amylase 36 IU/L, total bilirubin 0.42 mg/dL and lowered albumin of 2.7 g/dL.

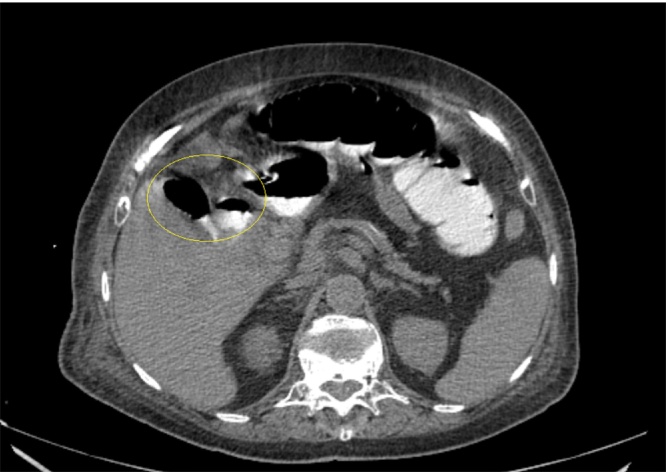

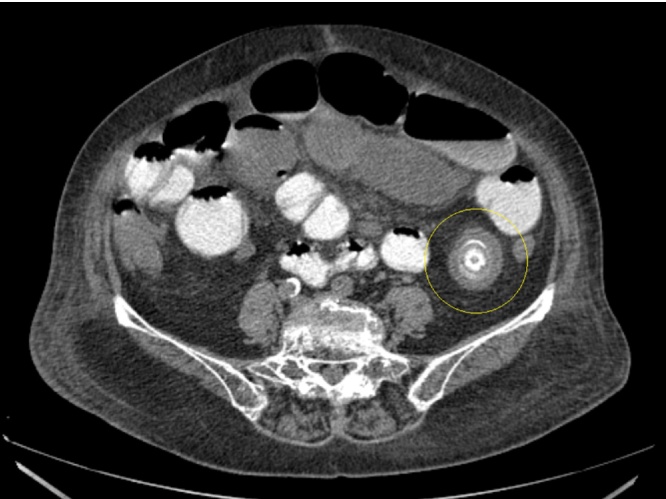

A plain abdominal radiograph was performed, showing unspecified bowel distension. Further CT examination revealed the presence of a cholecystoduodenal fistula with gas in the gall bladder, distended small bowel segments and a rim-calcified gallstone ≥2.5 cm inside the small bowel lumen (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). The inability of gastrografin to progress further in the bowel lumen after the impacted gallstone indicated a complete obstruction.

Fig. 1.

CT examination showing a cholocystoduodenal fistula with air and gastrografin inside the gall bladder.

Fig. 2.

CT examination showing bowel distension and a 2 cm in diameter calcified gallstone inside the small bowel lumen.

After admission, patient started therapy on IV antibiotics. A nasogastric tube was inserted with no retrograde flow of gastric content. Her clinical condition was serious but stable after 20 h of conservative therapy. The size and location of the gallstone pointed us towards surgical therapy, since it would be very unlikely for a gallstone of this size to pass through the ileocaecal valve. After written consent, the patient was taken to the operating room.

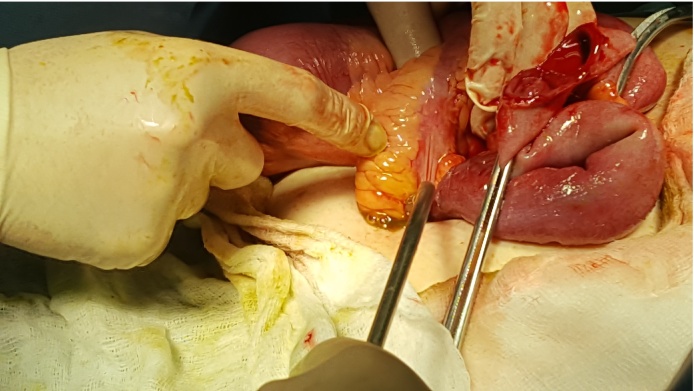

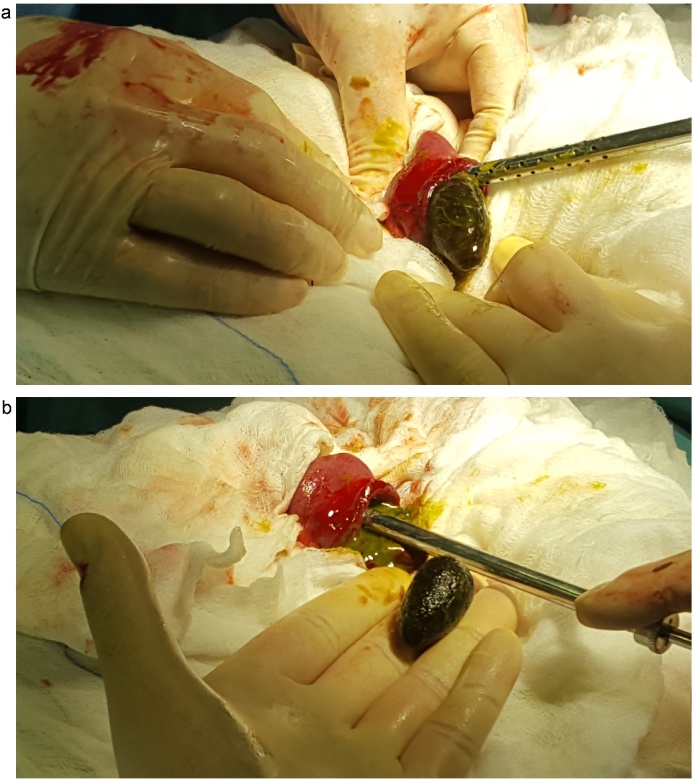

Under general anesthesia, a small infraumbilical incision was performed. Upon entering the abdominal cavity, examination of the small bowel started through palpation, to locate the gallstone. During handling of the bowel, we noticed enteric content inside the abdominal cavity, and further examination revealed a rupture in the antimesenteric part of the small bowel wall, approximately 60 cm from the ileocaecal valve (Fig. 3). Macroscopically, the segment of the bowel at the rupture site was discolored. Further on, a 3.2 cm egg-shaped gallstone was located in the terminal ileum near the ileocaecal valve, which was advanced upwards, and removed through the ruptured bowel (Figs. 4, 5a,b and 6 ). After removal of the gallstone, the intestine regained its peristalsis. The ruptured bowel wall had adequate blood perfusion, so a debridement and suturing was performed, with no resection (Fig. 7).

Fig. 3.

Bowel rupture site.

Fig. 4.

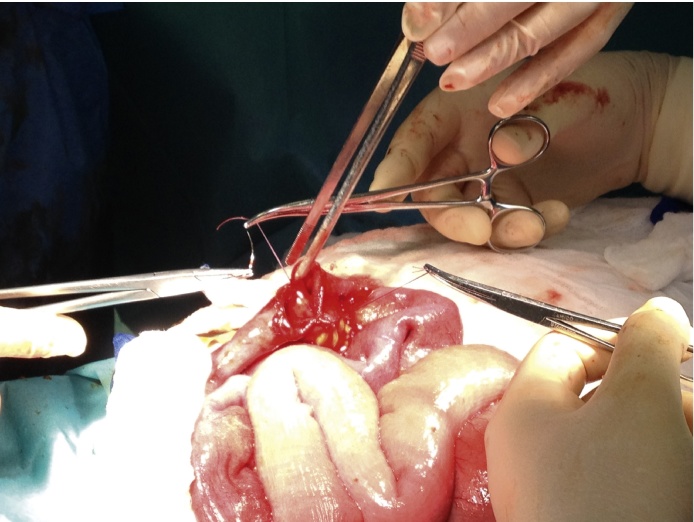

The location of the gallstone inside the bowel lumen and near the terminal ileum. Next to it the ruptured bowel segment.

Fig. 5.

(a,b) Removal of the gallstone through the ruptured site.

Fig. 6.

A 3.2 cm gallstone found to be the cause of the obstruction.

Fig. 7.

Suturing of the ruptured bowel.

Post-surgical clinical course was uneventful with the patient reporting normal defecation on the 3rd postoperative day. She was discharged uneventfully on the 6th day, with no further reports of abdominal pain or vomit at 6 month follow up.

3. Discussion

Gastrointestinal obstruction because of a gallstone is a rare form of mechanical obstructive ileus. It is caused by the passing and impaction of a gallstone in the bowel lumen, usually through a fistula connecting the gall bladder with the gastrointestinal tract. It grounds for 0.3–5.3% of all bowel obstruction causes [1]. The fistula is created due to the inflamed gall bladder being in contact with segments of the bowel and the pressure caused from a gallstone on the bladder wall. Recurrent episodes of cholecystitis also play a major role in the formation of the fistula [2]. The most common site of connection is the duodenum (69–70%), then parts of the colon (14%) and the small bowel (6%) [1], [3]. Presentation can be with nonspecific abdominal symptoms including nausea, vague abdominal pain and vomiting, or as a typical bowel obstruction manifestation, with acute abdominal pain and distension. Patients usually report a medical history of gallstones or recurrent episodes of cholecystitis up to 80% of cases [2], [4]. Gallstone ileus seems to appear more frequently in elderly population above the age of 65, showing a preference in women, since they are more prone to acute or chronic cholecystitis than men, with a ratio of 3–1 [1], [3], [5]. Our patient reported no such medical history, although she did report recurrent episodes of diarrhea for the past 8 months. We speculate those episodes might be due to bile acid dripping inside the bowel lumen from an existing fistula which got enlarged and allowed passage of the gallstone [6]. Unfortunately, no radiological examinations were performed over the past 10 years to confirm the presence of gallstones or chronic cholecystitis.

Rigler’s triad, described by Leo George Rigler in 1941, is a combination of radiological findings specific for bowel obstruction due to gallstones. It consists of gas in the billiary tree, small bowel obstruction and the presence of a gallstone inside the bowel lumen [3], [6], [7], [8]. Our patient had no findings on the plain abdominal radiograph, but had all three of Rigler’s findings in the CT examination. Computed tomography has a sensitivity of up to 93% for gallstone obstruction. In up to 14.8% of cases it is possible to also identify the biliogastric fistula [2]. Preoperative diagnosis, knowledge of location and number of gallstones inside the bowel lumen play a major role in the decision management regarding treatment.

There is an assortment of modalities regarding therapy for gallstone bowel obstruction. Those include conservative, surgical and non-surgical methods. Usually, gallstones ≥2–2.5 cm are able to cause a complete obstruction, therefore smaller gallstones can present as ‘rolling stones’ moving inside the bowel lumen and causing a phenomenon called ‘tumbling phenomenon’ [1]. Patients can be helped with the use of laxatives in order to defecate smaller gallstones and dissolve the obstruction. Non-surgical methods include endoscopic extraction of the gallstones or the application of U/S guided extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) [2], [5], [9], [10]. Surgical management of gallstone obstruction has seen much controversy with two methods being the most applied ones. There is a one-stage surgical procedure in which the gallstone is removed after an enterotomy, the biliogastric fistula is repaired and a cholecystectomy is performed. A two-stage procedure involves the removal of the gallstone at first, and repair of the fistula with cholecystectomy after four to six weeks [2], [3]. One-stage procedure is reported having a mortality rate of up to 16.7%, while the two-stage approach of up to 11.7% [2]. The choice of treatment is tailored to each patient, with surgical experience playing a major role, since the one-staged approach is a much more complex and technically demanding procedure.

In our case, the age of the patient along with her comorbidities led to the decision of performing a conservative surgical approach, with removal of the gallstone and no repair of the fistula. We speculate the gallstone was impacted on the ruptured location, weakened the bowel wall and caused perforation during manipulation of the bowel. It advanced afterwards further down the gastrointestinal tract where it was located. An enterotomy wasn’t necessary, since the gallstone was recovered through the ruptured site. It was decided not to perform the second stage of the procedure; that would put our patient in unnecessary and unjustified risk.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, although a rare clinical manifestation, gallstone ileus must be suspected in elderly patients with bowel obstruction symptoms and recurrent episodes of cholecystitis. A good medical history along with a CT examination is usually able to set the diagnosis. Treatment plan must be tailored to each patient individually, according to his age and comorbidities. In our case, despite the size of the gallstone the obstruction was resolved successfully, with an uneventful postoperative recovery.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

Nothing to declare.

Ethical approval

Nothing to declare.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

GS wrote the manuscript. GS, KM, PD, AT contributed on data acquisition and analysis. CM performed the operation with the help of GS and KM. CM supervised the manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final version of the submitted manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The work has been reported in line with the CARE criteria.

Gagnier J.J., Kienle G., Altman D.G., Moher D., Sox H., Riley D., et al. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2014; 67(1): 46–51.

The authors would like to thank Nikolaos Beis for his help during preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Apollos J.R., Guest R.V. Recurrent gallstone ileus due to a residual gallstone: a case report and literature review. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2015;13:12–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nuno-Guzman C.M., Marin-Contreras M.E., Figueroa-Sanchez M., Corona J.L. Gallstone ileus: clinical presentation, diagnostic and treatment approach. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2016;8(1):65–76. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conzo G., Mauriello C., Gambardella C., Napolitano S., Cavallo F., Tartaglia et al E. Gallstone ileus: one-stage surgery in an elderly patient: one-stage surgery in gallstone ileus. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2013;4(3):316–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayantunde A.A., Agrawal A. Gallstone ileus: diagnosis and management. World J. Surg. 2007;31(6):1292–1297. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee C.H., Yin W.Y., Chen J.H. Gallstone ileus with jejunum perforation managed with laparoscopic-assisted surgery: rare case report and minimal invasive management. Int. Surg. 2015;100(5):878–881. doi: 10.9738/INTSURG-D-14-00265.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Julian Walters R.F., Sanjeev Pattni S. Managing acid bile diarrhea. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2010;3(November (6)):349–357. doi: 10.1177/1756283X10377126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rigler L.G., Borman C.N., Noble J.F. Gallstone obstruction: pathogenesis and roentgen manifestations. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1941;117:1753–1759. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaduputi V., Tariq H., Rahnemai-Azar A.A., Dev A., Farkas D.T. Gallstone ileus with multiple stones: where Rigler triad meets Bouveret’s syndrome. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2015;7(12):394–397. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v7.i12.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qasaimeh G.R., Bakkar S., Jadallah K. Bouveret’s syndrome: an overlooked diagnosis: a case report and review of literature. Int. Surg. 2014;99(6):819–823. doi: 10.9738/INTSURG-D-14-00087.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pezzoli A., Maimone A., Fusetti N., Pizzo E. Gallstone ileus treated with non-surgical conservative methods: a case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2015;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]