Abstract

Between 1997 and 2000 a single multidrug-susceptible methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone, M (sequence type 30 [ST30]-staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec [SCCmec] type IV), was present in a pediatric hospital in Mexico City, Mexico. In 2001 the international multidrug-resistant New York-Japan clone (ST5-SCCmec type II) was introduced into the hospital, completely replacing clone M by 2002.

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most important human pathogens causing skin and tissue infections, deep abscess formation, pneumonia, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, toxic shock syndrome, and bacteremia (34). The emergence of penicillin-, methicillin-, and, recently, high-level vancomycin-resistant strains (7-9) showed that S. aureus could easily adapt to antibiotic pressure and acquire resistance genes of heterologous origin. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), besides having established itself in the hospital setting, is now beginning to appear in the wider community as well as among people without typical associated risk factors for MRSA acquisition (18, 19). There are only a limited number of nosocomial MRSA clones spread worldwide (15, 28), and the genetic backgrounds of community-acquired MRSA strains do not correspond to that of hospital-acquired MRSA in the same geographic region (35). The success in colonization and production of disease by this bacterium is largely due to the expression of a battery of virulence factors, which promote adhesion, acquisition of nutrients, and evasion of the host immunologic response (23).

The prevalence of resistant bacteria has been increasing rapidly in Mexican hospitals during the last few years. According to different studies performed in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000, the prevalence of MRSA in Mexican hospitals was estimated to vary from 7 to 30% (5, 6, 21, 33). However, reports from Mexico documenting the clonality of MRSA isolates are very scarce, and to the best of our knowledge there was just one publication describing the molecular characterization of isolates from Mexico (4).

The aim of the present study was to define the MRSA clonal types and their evolution over time (1997 to 2003) in a tertiary care pediatric hospital in Mexico City by different molecular typing methods, including pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), spa typing, multilocus sequence typing (MLST), and staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) typing. Additionally, the presence of several staphylococcal virulence determinants and accessory gene regulator (agr) types was also determined in the different MRSA clones.

A total of 659 S. aureus strains were isolated at the Hospital de Pediatría of Centro Médico Nacional, Siglo XXI-IMSS, in Mexico City, Mexico, between January 1997 and May 2003. During this period a total of 98 single-patient S. aureus isolates were identified as MRSA, each of which was available for molecular typing. The frequency of MRSA varied between 17 and 23% of the total of S. aureus isolates during the 5 years up to 2001, after which it dropped to 4% in 2002 and to 0% in 2003. The decrease in the frequency of MRSA strains since 2002 was most probably related to the intervention of the infection control committee of the hospital at the end of 2001.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by the MicroScan automated method (Dade-Behring, Sacramento, Calif.) for penicillin, oxacillin, amoxicillin, cefotaxime, cephalothin, cefazolin, imipenem, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, clindamycin, erythromycin, clarithromycin, gentamicin, rifampin, tetracycline, and vancomycin. The MIC of vancomycin was determined by broth microdilution according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) guidelines (25).

PFGE of SmaI digests of chromosomal DNAs (10), hybridization of SmaI digests with a Tn554 probe (12), spa typing (32), MLST (14), and SCCmec typing (26) were performed as previously described. For spa typing and MLST, sequences of both strands were determined at Macrogen, Seoul, South Korea.

Sequences specific for the genes encoding staphylococcal enterotoxins A to E (SEA to SEE, respectively) and G to J (SEG to SEJ, respectively) and the toxic shock syndrome toxin were detected by a multiplex PCR strategy (24). Beta, gamma, and gamma variant hemolysins; exfoliatin toxins A, B, and D (ETA, ETB, and ETD); Panton-Valentine leukocidin; leukocidin LukE-LukD; and exotoxin of the epidermal cell differentiation inhibitor were detected as previously described (20, 35). The agr type was determined by PCR as described elsewhere (16).

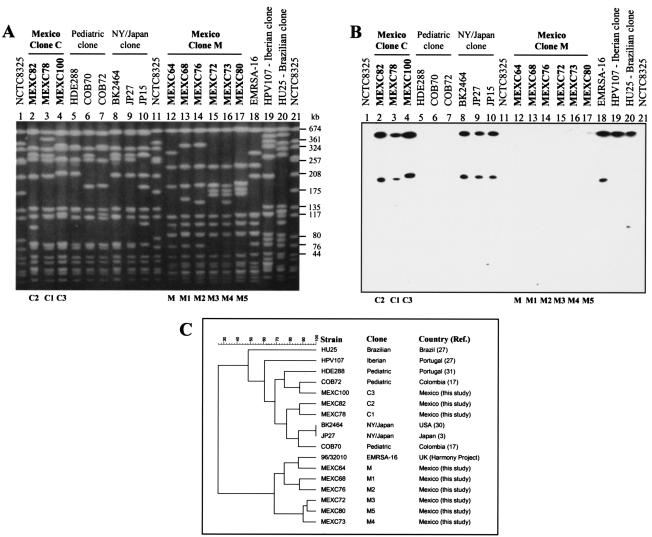

The 98 MRSA isolates were distributed into two PFGE types, M (six subtypes) and C (three subtypes) (Fig. 1A). All 75 MRSA isolates recovered between 1997 and 2000 belonged to clone M. In 2001 clones M and C represented 39 and 61% of the isolates, respectively, and in 2002 clone M was completely replaced by clone C. The 82 isolates classified as PFGE pattern M belonged to a clear major subtype, M (n = 65), and interestingly, all isolates collected during 2001 belonged to the second most frequent subtype, M5 (n = 7). Each of the remaining subtypes of pattern M included fewer than five isolates. Clone C was represented by 16 isolates, out of which the large majority (n = 14) belonged to subtype C1.

FIG. 1.

(A) SmaI PFGE patterns of the MRSA clones found in the Hospital de Pediatría of Centro Médico Nacional, Siglo XXI-IMSS, Mexico City, Mexico, and international MRSA clones. (B) SmaI PFGE of panel A hybridized with a Tn554 probe. (C) Dendrogram of data from panel A. The relatedness among PFGE profiles was evaluated by using Bionumerics software (version 3.0; Applied Maths, Ghent, Belgium). Patterns were clustered by the unweighted pair group method using arithmetic averages, and the similarity coefficients were generated from a similarity matrix calculated with the Jaccard coefficient. NY, New York; USA, United States; UK, United Kingdom.

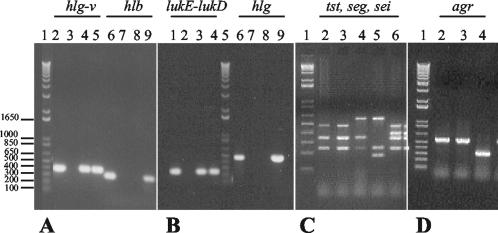

Clones M and C could be easily distinguished not only by PFGE but also by antibiogram and other molecular properties as well (Table 1). (i) Clone M showed a limited pattern of resistance (resistance to β-lactams and gentamicin only), while clone C was multidrug resistant (resistance to β-lactams, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, and erythromycin). (ii) The hybridization with a Tn554 probe of one representative of each PFGE subtype found in the present study (subtypes M to M5 and C1 to C3) indicated that strains belonging to clone M did not have homology with transposon Tn554, while strains characterized by PFGE pattern C carried two copies of Tn554 in SmaI fragments of approximately 646 and 200 kb (Fig. 1B). (iii) Representatives of clone C (two isolates belonging to the clearly dominant subtype C1) showed spa type 2 (TJMBMDMGMK), sequence type 5 (ST5), and SCCmec type II, whereas representatives of the two major clone M subtypes (one isolate of M and one isolate of M5) were characterized by spa type 183 (WGKAKAOKMQ), ST30, and SCCmec type IV. (iv) The same isolates were tested for the presence of virulence determinants and agr type, showing that clone C was positive for hlg-v (the gamma-hemolysin variant gene) and lukE-lukD, while clone M was positive for hlb (the beta-hemolysin gene), hlg (the gamma-hemolysin gene), and tst (the toxic shock syndrome toxin gene). Clone C was of agr type 2, and clone M was of agr type 3. Figure 2 shows the agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products of virulence determinants and agr group for representatives of clones C and M.

TABLE 1.

Phenotypic and genotypic properties of the two MRSA clones present in a pediatric hospital in Mexico City, Mexico (1997 to 2003)

| Property | Result for clone:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| M | C | |

| Antibiograma | β-Lactams, GEN | β-Lactams, GEN, CIP, CD, ERYb |

| PFGE pattern | M-M5 | C1 to C3 |

| spa typec | 183 (WGKAKAOKMQ) | 2 (TJMBMDMGMK) |

| ST | 30 | 5 |

| SCCmec type | IV | II |

| agr type | 3 | 2 |

| Virulence gened | ||

| hlg-v | − | + |

| hlg | + | − |

| lukE-lukD | − | + |

| tst | + | − |

| seg | + | + |

| sei | + | + |

| hlb | + | − |

Antibiotic abbreviations: GEN, gentamicin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CD, clindamycin; ERY, erythromycin.

Two isolates were also resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

spa types 2 and 183 were assigned according to the work of Shopsin et al. (32) or to the work of B. N. Kreiswirth and S. Naidich (personal communication), respectively.

Results for virulence genes absent in both clones (Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes, edinAC, eta, etb, etd, sea, seb, sec, sed, see, seh, sej, sek, sel, and sem) are not presented; +, presence of toxin gene; −, absence of toxin gene.

FIG. 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products of virulence determinants and agr group. (A) hlg-v and hlb. Lane 1, 1 Kb Plus (Gibco BRL); lanes 2 to 5 (hlg-v), RIMD 31092 (positive control), MEXC80 (clone M), MEXC79 (clone C), and MEXC78 (clone C), respectively; lanes 6 to 9 (hlb), NCTC 7428 (positive control), MEXC79, MEXC78, and MEXC80, respectively. (B) lukE-lukD and hlg. Lanes 1 to 4 (lukE-lukD), FRI-913 (positive control), MEXC80, MEXC79, and MEXC78, respectively; lane 5, 1 Kb Plus (Gibco BRL); lanes 6 to 9 (hlg), ATCC 49775 (positive control), MEXC79, MEXC78, and MEXC80, respectively. (C) tst (559 bp), seg (327 bp), and sei (465 bp). Lane 1, 1 Kb Plus (Gibco BRL); lane 2, MEXC79; lane 3, MEXC78; lane 4, MEXC80; lane 5, FRI913 (see+ tst+); lane 6, FRI472 (seg+ sed+ sei+). Amplification of a 228-bp band corresponding to 16S rRNA was used as an internal control. (D) agr group. Lane 1, 1 Kb Plus (Gibco BRL); lanes 2 to 4, MEXC79 (type 2), MEXC78 (type 2), and MEXC80 (type 3), respectively. Numbers at left are molecular sizes in kilobases.

Clone M, previously designated the Mexican clone (4), was also found in a hospital in Patras, Greece, and is related to the EMRSA-16 clone (1). Although representatives of the Mexican clone M and of EMRSA-16 showed very similar PFGE patterns (one-band difference [Fig. 1A]), they had distinct sequence types (ST30 and ST36, respectively) and SCCmec types (type IV and type II, respectively, which in part explains the multidrug resistance of the latter clone). Therefore, it is important that clones be identified by a combination of molecular typing methods, namely, PFGE, MLST, and SCCmec typing, as previously pointed out by others (15, 28). Curiously, although clone M represented all the MRSA isolates found between 1997 and 2000 at the pediatric hospital in Mexico City, it has not been reported in other countries of Latin America so far.

As previously shown in other studies from our laboratory (2), clone M, which showed a limited resistance pattern, was replaced by a more resistant clone, clone C. One isolate belonging to each subtype of clone C (C1 to C3) was compared to strains belonging to previously characterized MRSA clones sharing identical sequence types (ST5), i.e., representatives of the pediatric clone and isolates belonging to the New York-Japan clone and also to other international pandemic clones, namely, the Iberian, Brazilian, and EMRSA-16 clones (Fig. 1C). Clone C showed a high degree of similarity to the pediatric (75.9%) and the New York-Japan (77.7%) clones (Fig. 1C). The multidrug-resistant New York-Japan clone (3, 30) and the multidrug-susceptible pediatric MRSA clone (31) shared very similar spa types; spa type 2 (TJMBMDMGMK) and spa type 45 (TJMBDMGMK), respectively, were both ST5 but differed in the type of SCCmec (types II and IV, respectively) (27). The isolates found in Colombia in 1996 to 1998 that belonged to the pediatric clone harbored SCCmec type IV (27). The combination of characteristics strongly suggested that clone C, found at the pediatric hospital in Mexico since 2001, was very similar to the multiresistant New York-Japan clone, which was widely spread in different states of the United States (11, 22, 29, 30), and to the clone spread in Colombia in 1996 to 1998 (17). Therefore, clone C belongs to the New York-Japan lineage and might have been transferred from the United States to Mexico. The replacement of a multidrug-susceptible clone by this multiresistant clone that has spread in a pediatric hospital could create a serious public health threat since the therapeutic options would become even more limited. In addition, seven out of the eight vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus strains isolated in the United States (22) and the first two high-level vancomycin-resistant S. aureus isolates (7, 9), which acquired in vivo Tn1546 from Enterococcus faecalis, belonged to the New York lineage (22, 36), reinforcing concerns of potential emergence of similar vancomycin-resistant S. aureus strains in Mexico.

Eady and Cove (13) suggested that MRSA isolates associated with community-acquired skin and soft tissue infections could represent the displacement of some hospital clones, namely, the EMRSA-15 clone, the pediatric clone, and the gentamicin-susceptible MRSA from French hospitals, all harboring SCCmec type IV and therefore showing a limited susceptibility pattern similar to that of community-acquired MRSA. Besides containing SCCmec type IV, community-acquired MRSA also usually belongs to agr type 3 (35), as is the case with clone M from Mexico. The overall characteristics of the Mexican clone suggest that it may be a candidate for transfer from the hospital to the community.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, Cuernavaca, Morelos, México, and by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Lisbon, Portugal, within project POCTI/1999/ESP/34872 awarded to H. de Lencastre. M. E. Velazquez-Meza is a Ph.D. fellow at the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Iztapalapa and was supported by grant 176380 of program C/PFPN-2002-35-32 PIFOP-Conacyt, México, and by project CEM/NET 31 from IBET awarded to H. de Lencastre.

We thank Barry N. Kreiswirth and Steve Naidich for the new spa assignment, spa type 183.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aires de Sousa, M., C. Bartzavali, I. Spiliopoulou, I. Santos Sanches, M. I. Crisostomo, and H. de Lencastre. 2003. Two international methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones endemic in a university hospital in Patras, Greece. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2027-2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aires de Sousa, M., and H. de Lencastre. 2004. Bridges from hospitals to the laboratory: genetic portraits of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 40:101-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aires de Sousa, M., H. de Lencastre, I. Santos Sanches, K. Kikuchi, K. Totsuka, and A. Tomasz. 2000. Similarity of antibiotic resistance patterns and molecular typing properties of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates widely spread in hospitals in New York City and in a hospital in Tokyo, Japan. Microb. Drug Resist. 6:253-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aires de Sousa, M., M. Miragaia, I. S. Sanches, S. Avila, I. Adamson, S. T. Casagrande, M. C. Brandileone, R. Palacio, L. Dell'Acqua, M. Hortal, T. Camou, A. Rossi, M. E. Velazquez-Meza, G. Echaniz-Aviles, F. Solorzano-Santos, I. Heitmann, and H. de Lencastre. 2001. Three-year assessment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Latin America from 1996 to 1998. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2197-2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alpuche, A. C., F. C. Avila, D. M. Espinoza, B. D. Gómez, and P. J. I. Santos. 1989. Perfiles de sensibilidad antimicrobiana de Staphylococcus aureus en un hospital pediatríco: prevalencia de resistencia a meticilina. Bol. Med. Hosp. Infant. Mex. 11:697-699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calderón, J. E., D. M. Espinoza, and B. R. Avila. 2002. Epidemiology of drug resistance: the case of Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase negative staphylococci infections. Salud Pública Méx. 44:108-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2004. Brief report: vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus—New York, 2004. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 53:322-323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002. Public health dispatch: vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Pennsylvania, 2002. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51:902-903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002. Staphylococcus aureus resistant to vancomycin, United States, 2002. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 51:565-567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung, M., H. de Lencastre, P. Matthews, A. Tomasz, I. Adamsson, M. Aires de Sousa, T. Camou, C. Cocuzza, A. Corso, I. Couto, A. Dominguez, M. Gniadkowski, R. Goering, A. Gomes, K. Kikuchi, A. Marchese, R. Mato, O. Melter, D. Oliveira, R. Palacio, R. Sá-Leão, I. Santos Sanches, J. H. Song, P. T. Tassios, and P. Villari. 2000. Molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: comparison of results obtained in a multilaboratory effort using identical protocols and MRSA strains. Microb. Drug Resist. 6:189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung, M., G. Dickinson, H. de Lencastre, and A. Tomasz. 2004. International clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in two hospitals in Miami, Florida. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:542-547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Lencastre, H., I. Couto, I. Santos, J. Melo-Cristino, A. Torres-Pereira, and A. Tomasz. 1994. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease in a Portuguese hospital: characterization of clonal types by a combination of DNA typing methods. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 13:64-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eady, E. A., and J. H. Cove. 2003. Staphylococcal resistance revisited: community-acquired methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus—an emerging problem for the management of skin and soft tissue infections. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 16:103-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enright, M. C., N. P. Day, C. E. Davies, S. J. Peacock, and B. G. Spratt. 2000. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1008-1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enright, M. C., D. A. Robinson, G. Randle, E. J. Feil, H. Grundmann, and B. G. Spratt. 2002. The evolutionary history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7687-7692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilot, P., G. Lina, T. Cochard, and B. Poutrel. 2002. Analysis of the genetic variability of genes encoding the RNA III-activating components Agr and TRAP in a population of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from cows with mastitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4060-4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomes, A. R., I. S. Sanches, M. Aires de Sousa, E. Castaneda, and H. de Lencastre. 2001. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Colombian hospitals: dominance of a single unique multidrug-resistant clone. Microb. Drug Resist. 7:23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorak, E. J., S. M. Yamada, and J. D. Brown. 1999. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospitalized adults and children without known risk factors. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:797-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hussain, F. M., S. Boyle-Vavra, and R. S. Daum. 2001. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in healthy children attending an outpatient pediatric clinic. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 20:763-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarraud, S., C. Mougel, J. Thioulouse, G. Lina, H. Meugnier, F. Forey, X. Nesme, J. Etienne, and F. Vandenesch. 2002. Relationships between Staphylococcus aureus genetic background, virulence factors, agr groups (alleles), and human disease. Infect. Immun. 70:631-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macia, H., V. Medina, and R. Gaona. 1993. Estafilococos resistentes a meticilina en un hospital general de León, Guanajuato. Enferm. Infect. Microbiol. 3:123-127. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDougal, L. K., C. D. Steward, G. E. Killgore, J. M. Chaitram, S. K. McAllister, and F. C. Tenover. 2003. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing of oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from the United States: establishing a national database. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5113-5120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monday, S. R., and G. A. Bohach. 1999. Properties of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins and toxin shock syndrome toxin-1, p. 589-610. In J. E. Alouf and J. H. Freer (ed.), The comprehensive sourcebook of bacterial protein toxins, 2nd ed. Academic Press, London, England.

- 24.Monday, S. R., and G. A. Bohach. 1999. Use of multiplex PCR to detect classical and newly described pyrogenic toxin genes in staphylococcal isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3411-3414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Eleventh informational supplement: vol. 21, no. 1. Approved standard M2-A7. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 26.Oliveira, D. C., and H. de Lencastre. 2002. Multiplex PCR strategy for rapid identification of structural types and variants of the mec element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2155-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliveira, D. C., A. Tomasz, and H. de Lencastre. 2001. The evolution of pandemic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: identification of two ancestral genetic backgrounds and the associated mec elements. Microb. Drug Resist. 7:349-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliveira, D. C., A. Tomasz, and H. de Lencastre. 2002. Secrets of success of a human pathogen: molecular evolution of pandemic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2:180-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts, R. B., M. Chung, H. de Lencastre, J. Hargrave, A. Tomasz, D. P. Nicolau, J. F. John, Jr., and O. Korzeniowski. 2000. Distribution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones among health care facilities in Connecticut, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Microb. Drug Resist. 6:245-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts, R. B., A. de Lencastre, W. Eisner, E. P. Severina, B. Shopsin, B. N. Kreiswirth, A. Tomasz, et al. 1998. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in 12 New York hospitals. J. Infect. Dis. 178:164-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sa-Leão, R., I. Santos Sanches, D. Dias, I. Peres, R. M. Barros, and H. de Lencastre. 1999. Detection of an archaic clone of Staphylococcus aureus with low-level resistance to methicillin in a pediatric hospital in Portugal and in international samples: relics of a formerly widely disseminated strain? J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1913-1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shopsin, B., M. Gomez, S. O. Montgomery, D. H. Smith, M. Waddington, D. E. Dodge, D. A. Bost, M. Riehman, S. Naidich, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 1999. Evaluation of protein A gene polymorphic region DNA sequencing for typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3556-3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solano, L. I., H. E. Urdez, and V. R. Fajardo. 1999. Infecciones intrahospitalarias (IIH) causadas por estafilococos resistentes a meticilina (EMR), p. 418-460. In Enfermedades y Infecciones Microbiológicas. XXIV Congreso Anual de la Asociación Mexicana de Infectología y Microbiología Clínica, vol. 19. Asociación Mexicana de Infectología y Microbiología Clínica, Mexico City, Mexico.

- 34.Tenover, F. C., and R. P. Gaynes. 2000. The epidemiology of Staphylococcus infections, p. 414-421. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferretti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 35.Vandenesch, F., T. Naimi, M. C. Enright, G. Lina, G. R. Nimmo, H. Heffernan, N. Liassine, M. Bes, T. Greenland, M. E. Reverdy, and J. Etienne. 2003. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes: worldwide emergence. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:978-984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weigel, L. M., D. B. Clewell, S. R. Gill, N. C. Clark, L. K. McDougal, S. E. Flannagan, J. F. Kolonay, J. Shetty, G. E. Killgore, and F. C. Tenover. 2003. Genetic analysis of a high-level vancomycin-resistant isolate of Staphylococcus aureus. Science 302:1569-1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]