Abstract

Noble metal nanoparticles (NPs) such as silver (Ag) and gold (Au) have unique plasmonic properties that give rise to surface enhanced Raman scattering (SERS). Generally, Ag NPs have much stronger plasmonic properties and, hence, provide stronger SERS signals than Au NPs. However, Ag NPs lack the chemical stability and biocompatibility of comparable Au NPs and typically exhibit the most intense plasmonic resonance at wavelengths much shorter than the optimal spectral region for many biomedical applications. To overcome these issues, various experimental efforts have been devoted to the synthesis of Ag/Au hybrid NPs for the purpose of SERS detections. However, a complete understanding on how the SERS enhancement depends on the chemical composition and structure of these nanoparticles has not been achieved. In this study, Mie theory and the discrete dipole approximation have been used to calculate the plasmonic spectra and near-field electromagnetic enhancements of Ag/Au hybrid NPs. In particular, we discuss how the electromagnetic enhancement depends on the mole fraction of Au in Ag/Au alloy NPs and how one may use extinction spectra to distinguish between Ag/Au alloyed NPs and Ag-Au core-shell NPs. We also show that for incident laser wavelengths between ∼410 nm and 520 nm, Ag/Au alloyed NPs provide better electromagnetic enhancement than pure Ag, pure Au, or Ag-Au core-shell structured NPs. Finally, we show that silica-core Ag/Au alloy shelled NPs provide even better performance than pure Ag/Au alloy or pure solid Ag and pure solid Au NPs. The theoretical results presented will be beneficial to the experimental efforts in optimizing the design of Ag/Au hybrid NPs for SERS-based detection methods.

I. INTRODUCTION

The current landscape of noble metal nanoparticle (NP) research is one of great diversity owing to the unique plasmonic properties of silver (Ag) and gold (Au) and their potential applications in chemical and biomolecular sensing, imaging, and catalysis.1–10 Both Ag and Au NPs have been found to greatly enhance the Raman signals of adsorbed small molecules.11–16 This surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) effect has been primarily utilized for the detection of chemical and biological species in trace amounts. Because SERS provides finger-print spectra, it is less likely to suffer from background signal interference than other detection methods. When combined with the signal enhancement provided by noble metal NPs, SERS becomes advantageous for the detection of these trace species. Although chemical effects account for a portion of SERS signal enhancement, the primary source of this phenomenon in metal NPs is generally attributed to the electromagnetic enhancement around NP surfaces.17,18 Upon irradiation, noble metals exhibit surface plasmon resonance (SPR), a coherent oscillation of the “free” conduction band electrons at the metal surface. When the dimensions of the metal are smaller than the wavelength of incident light, the conduction band electrons oscillate collectively throughout the particle, a phenomenon known as localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR).19–22 These plasmon resonances generate large electric fields (E-fields) at the NP surface that can greatly enhance the signal intensities of both the incident and scattered photons in Raman spectroscopy.15 In addition to enhancing the E-fields at the NP surface, the LSPR of noble metal NPs gives rise to large absorption coefficients, typically in the visible and near-infrared (NIR) spectral regions.23 These optical properties are influenced by several physical characteristics of the system, including NP size, shape, and the dielectric properties of both the NP and the medium, the effects of which have been the subject of many studies.23–30

Ag NPs are known to exhibit more intense plasmonic properties than Au NPs of similar size and, consequently, provide greater SERS enhancements.31 However, the stronger enhancements by Ag NPs are often observed at shorter wavelengths of incident light than typically used for many Au NP applications. These wavelengths are often outside the optimal spectral region for many biomedical applications in which infrared or near-infrared incident light is preferable. In addition to these spectral differences, Ag NPs also lack the chemical stability and biocompatibility of Au NPs.6,32–36 These factors have limited the use of Ag NPs in biological detection applications. In order to achieve strong SERS enhancement while maintaining the stability and biocompatibility of Au NPs, numerous experimental efforts have been devoted to the development of hybrid nanomaterials that combine the strong plasmonic properties of Ag with the chemical stability and biocompatibility of Au.37–48 Because Ag and Au have nearly identical crystal structures, combining the two metals to prepare hybrid particles is fairly straightforward. Most commonly, Ag and Au are combined by the formation of core-shell structures41,47,49,50 or by alloying the two metals.51

The earliest work we have found regarding the preparation of Ag/Au alloyed NPs was presented by Papavassiliou51 who used an electric arc deposition method to prepare Ag/Au alloyed NPs of varying Au/Ag mole fraction. Another technique for the synthesis of Ag/Au alloyed NPs is the co-reduction of silver nitrate (AgNO3) and chloroauric acid (HAuCl4) in solution.37 However, the homogeneity of the Ag/Au alloyed NPs prepared via this method is questionable. Recently, Gao et al.43 have addressed this issue by annealing NPs at 1000 °C within a protective silica shell. The annealing process allows for atomic diffusion yielding chemically homogenous alloyed NPs. Although much progress has been made in the synthesis of Ag/Au alloyed NPs, a detailed theoretical understanding of SERS signal enhancements with respect to Ag/Au molar ratio is not currently available. Early on, an issue was encountered in that the extinction spectra of spherical Ag/Au alloyed NPs calculated by the Mie theory using a molar ratio proportionate average of the dielectric functions of Ag and Au to represent the dielectric function of an Ag/Au alloy did not match the experimentally measured extinction spectra of the same alloy.37 The theoretically calculated spectra exhibit two plasmonic peaks, while the experimental spectra show a single peak that red shifts with increasing Au mole fraction. In contrast, by using an experimentally measured dielectric function for an Ag/Au alloy thin film, for a given mole ratio, Link et al. were able to obtain the calculated extinction spectrum using the Mie theory that provided much better agreement with a corresponding experimental spectrum.37

It is desirable to calculate and predict the optical properties of Ag/Au alloyed NPs at any chemical composition prior to synthesis. One earlier study examined the extinction spectra and near-field enhancement for Ag/Au alloyed NPs;39 however, their calculations relied on composition-weighted averages of the dielectric responses of Ag and Au to represent Ag/Au alloys. Hence, these results were not reliable. Recently, Rioux et al.52 proposed an analytic model for the dielectric functions of Ag/Au alloys. Their analytic model effectively fits experimentally determined dielectric functions of Ag/Au alloy, Ag, and Au thin films and can accurately represent any alloy composition. They showed that the calculated extinction spectra of spherical Ag/Au alloyed NPs using their fitted empirical dielectric functions of the alloy compare very well with the experimental measured extinction spectra. However, these authors did not calculate the near-field electromagnetic enhancement, which is related to the SERS enhancement of such spherical Ag/Au alloyed NPs. We have made use of the progress of Rioux et al. and have theoretically investigated the near-field electromagnetic enhancement of Ag/Au alloyed NPs as a function of chemical composition. Additionally, we have compared the near-field enhancement effects of Ag/Au alloyed NPs with Ag-Au core-shell structured NPs of the same sizes and the same chemical composition and discussed how these two structures compare in terms of expected SERS enhancement.

II. THEORETICAL METHODS

A. SERS enhancement

The SERS enhancement expected from a NP is related to the near-field electromagnetic enhancement R(ω), , where E is the electric field near the surface of the NPs, E0 is the electric field amplitude of the incident light, and ω is the frequency of light. A common approximation for the SERS enhancement factor (EF) is given by SERS EF = R(ωi) R(ωs), where ωi is the frequency of incident light and ωs is the frequency of scattered light.31 For Raman detection, frequency differences between ωs and ωi are typically small, hence one may further assume SERS EF = R(ωi)2. In the current study, we focus on the dependence of R(ω) on the chemical composition and structure of Ag/Au hybrid NPs. We employed two approaches, the Mie theory and the Discrete Dipole Approximation (DDA) to calculate R(ω).

B. Mie theory

Calculations of light scattering and absorption by spherical core-shell and alloyed Ag/Au hybrid NPs can be done through the Lorentz-Mie theory which provides an exact analytical solution to the Maxwell equations.21,27,53–58 We have used the recursive algorithm developed by Wu and Wang57 and implemented the calculations according to the Mie theory in Mathematica® 9. The extinction efficiency, Qext, is calculated according to the equation as follows:

| (1a) |

| (1b) |

where R is the particle radius, Nm and Np are the complex refractive indices of the medium and particle, respectively, and an and bn are the Mie scattering coefficients obtained through the extended Mie theory solution for a multi-layered particle.

The surface-averaged near-field EF, , is given by59

| (2) |

where is the spherical Hankel function of the second kind.

C. Discrete dipole approximation

DDA is a well-known approximation method to solve Maxwell’s equations for the targets of arbitrary geometries for which exact solutions are not available. We used the DDSCAT 7.3 implementation of DDA. The DDA method has been widely used and is discussed in detail elsewhere.60–63 In brief, the particle is represented by N point dipoles with the material-specific polarizabilities αj at locations rj on a cubic lattice according to a specified geometry. The polarization (Pj) of each dipole at its location rj is given by

| (3) |

where Ej, the electric field at point rj, is a summation of the electric fields generated by all other dipoles, Eother,j (4b), plus the incident electric field, Einc,j (4a), where E0 is the amplitude and k is the wave vector of the incident light,

| (4a) |

| (4b) |

The contribution of the electric field at point j, by the dipole at point k, is found by summing over the term −AjkPk. The term Ajk is a 3 × 3 matrix given by

| (5a) |

| (5b) |

Once the polarizabilities (αj) are assigned, the resultant set of 3N linear equations can be solved through an iterative method to yield the electric field at each point dipole as well as the polarizations (Pj). The extinction and absorption cross sections of the target can be subsequently determined from the optical theory. The electric fields, |Ej|/|E0|, were obtained for all dipole locations within the particle volume and in an extended volume surrounding the particle and plotted with Mayavi. A sufficient number of dipoles (N = 106–107) were used such that the calculated DDA spectra have sufficient agreement with those calculated by the extended Mie theory.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A. Ag/Au alloyed nanoparticles

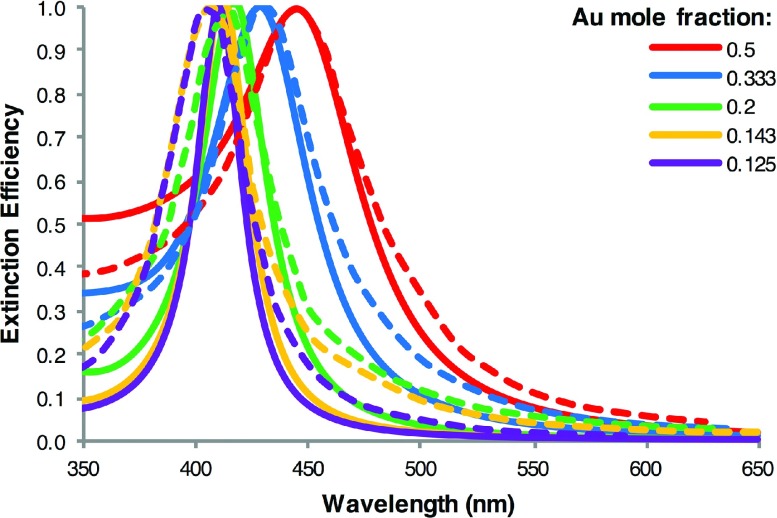

We first used the analytic model of dielectric function proposed by Rioux et al. to calculate the extinction spectra of Ag/Au alloyed NPs with dimensions and molar compositions corresponding to those of NPs synthesized by Gao et al.,43 which exhibited excellent chemical homogeneity and of high quality. Details of how these particles were prepared and characterized can be found in Ref. 43. Figure 1 compares our calculated extinction spectra with the experimentally reported spectra. For clarity, all spectra have been normalized by the peak intensity. The overall agreement between the calculated and experimental spectra is very good, especially in regard to the peak position. Size corrections to the thin film dielectric functions of Rioux et al. resulted in only minor changes to the refractive index values and, thus, are not included in our calculations.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the calculated extinction spectra (solid lines) with the experimental spectra of Gao et al. (dashed lines) for 20 nm Ag/Au alloyed NPs; the theoretical curves are calculated with Mie theory using the dielectric function data of Rioux et al.

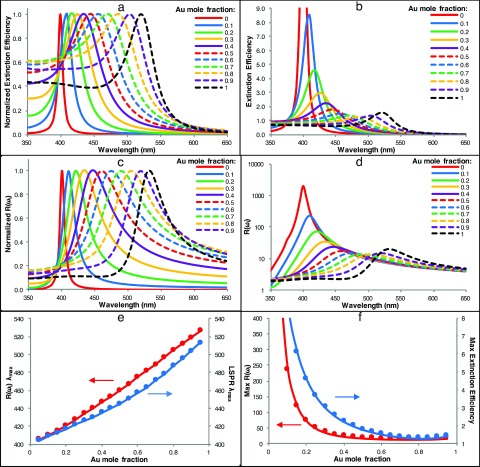

We have further used the Ag/Au alloy dielectric functions of Rioux et al. to calculate both the extinction spectra and wavelength dependent E-field EFs, R(ω), for Ag/Au alloyed NPs with Au mole fractions ranging from 0.0 to 1.0. Figure 2 presents these data to illustrate the effects of chemical composition on the extinction spectra and E-field enhancement.

FIG. 2.

(a) Normalized and (b) non-normalized extinction spectra, (c) normalized and (d) non-normalized wavelength dependent E-field EFs, R (ω), (e) λmax for R(ω) (red, primary y-axis) vs Au mole fraction and LSPR λmax (blue, secondary y-axis) vs Au mole fraction, and (f) max R(ω) (red, primary y-axis) vs Au mole fraction and max extinction efficiency (blue, secondary y-axis) vs Au mole fraction for 20 nm Ag/Au alloyed NPs.

As observed by others,37,43 in the extinction spectra of Ag/Au alloyed NPs, the LSPR λmax shifts almost linearly with increasing Au mole fraction, as shown in the normalized extinction spectra of 20 nm diameter Ag/Au alloyed NPs (Figure 2(a)). A similar plot of the normalized E-field EFs, as a function of wavelength, reveals a similar shift of λmax of R(ω) (Figure 2(c)). Figure 2(e) compares these two trends by plotting R(ω) λmax and LSPR λmax as a function of Au mole fraction. When compared with the LSPR λmax, the R(ω) λmax is red-shifted, generally to a greater degree for larger Au mole fractions. The maximum extinction efficiencies and maximum R(ω) values both demonstrate an exponential decrease in magnitude with increasing Au mole fraction (Figure 2(f)) up to a mole fraction of about 0.8. Further increase in Au mole fraction results in a slight increase of both the maximum R(ω) value and the extinction efficiency. This can be seen in the plots of the non-normalized extinction spectra and the E-field EF R(ω) spectra shown in Figures 2(b) and 2(d).

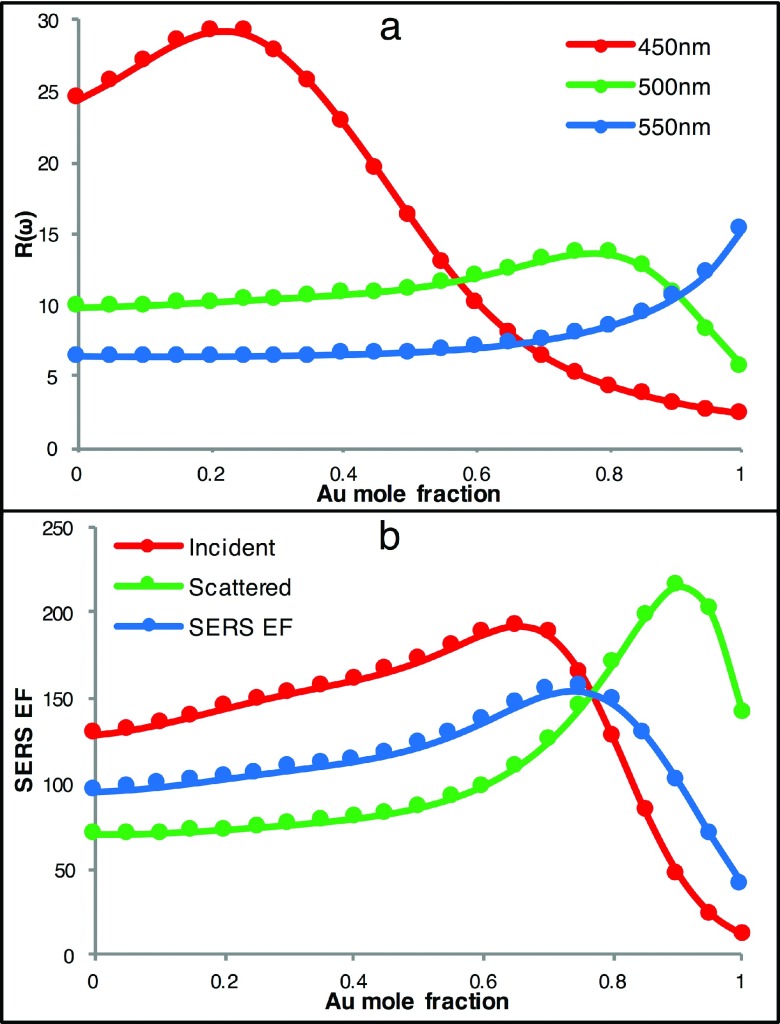

The SERS enhancement is largely determined by R(ω). From Figure 2(d), one can observe that pure Ag NPs have the largest R(ω) enhancement at λ = 410 nm, near the plasmonic peak of pure silver NPs. Away from that wavelength, there is still enhancement, although not as strong as at λ = 410 nm. Adding Au to make Ag/Au alloy NPs decreases the peak intensity significantly, but the enhancement at other wavelengths does not diminish significantly. To better illustrate the effects of chemical composition on these wavelength dependent SERS enhancements, we have plotted R(ω) as a function of Au mole fraction for three incident wavelengths (450 nm, 500 nm, and 550 nm) (Figure 3). These three wavelengths were chosen to demonstrate the E-field EF dependence on chemical composition. The E-field EF R(ω) has, in general, three types of wavelength-dependence on chemical compositions. For incident wavelengths of λ ∼ 410 nm or shorter, R(ω) decreases with increasing Au mole fraction (data not shown). For incident wavelengths between ∼410 nm and ∼520 nm, R(ω) is greatest for a chemical composition in between pure Ag and pure Au, as seen for λ = 450 nm and λ = 500 nm in Figure 3. This suggests that, for incident wavelengths in this range, Ag/Au alloyed NPs with an optimum chemical composition would have larger E-field EFs and, therefore, outperform both pure Ag and pure Au NPs. For wavelengths longer than ∼520 nm, the E-field enhancement increases with increasing Au mole fraction as seen for λ = 550 nm. For NIR incident light (λ > ∼ 700 nm), R(ω) is generally constant across all alloy compositions since spherical alloyed NPs do not provide large E-field enhancements in NIR region. One must rely on other nanostructures, such as ellipsoids or core-shell structures, to produce sufficient enhancement in the NIR region. We further note that, because the SERS EF is dependent on both R(ωi) and R(ωs), the maximum SERS enhancement as a function of chemical composition may differ from when only R(ωi) or R(ωs) is considered. Figure 3(b), for example, shows the peak shift in the calculated SERS EFs of Ag/Au alloyed NPs assuming SERS EF = R(ωi)2, SERS EF = R(ωs)2, or SERS EF = R(ωi) R(ωs).

FIG. 3.

(a) E-field EFs, R(ω), at three representative wavelengths (450 nm, 500 nm, and 550 nm) as a function of Au mole fraction for 20 nm Au/Ag alloyed NPs, (b) SERS EF at an incident wavelength in the visible region (R(ω)2 at 488 nm, red), a wavelength corresponding to a 1037 cm−1 Stokes shift (R(ω)2 at 514 nm, green), and the SERS EF = R(ωi) R(ωs) (blue).

B. Ag-Au core-shell structured NPs

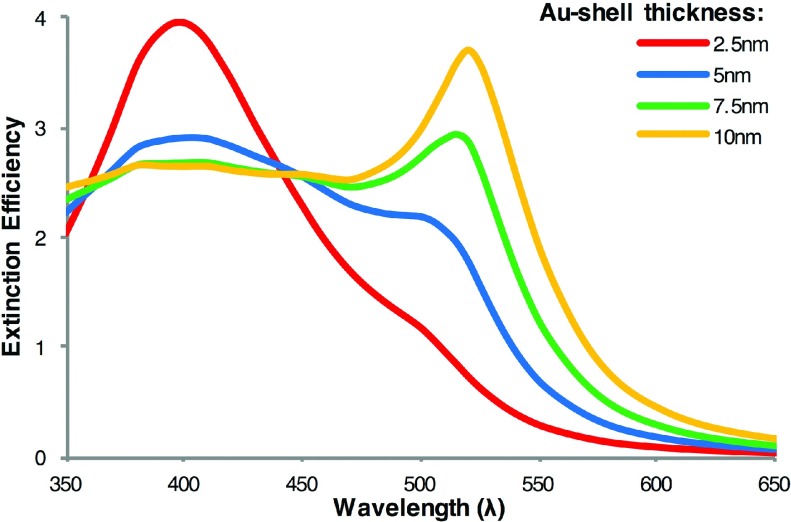

Ag-Au core-shell structured NPs are also of great interest for SERS detections. An outer Au shell provides chemical and biological stability to the more strongly plasmonic Ag core. The plasmonic properties of Ag-Au core-shell structured NPs can be tuned by tuning the shell thickness with respect to the core radius. Figure 4 presents the extinction spectra for Ag-Au core-shell structured NPs with a fixed size of Ag core and varied Au shell thickness. The extinction spectra of Ag-Au core-shell NPs are very different from those of Ag/Au alloyed NPs. While the spectra of Ag/Au alloyed NPs consist of single peaks that red shift with increasing Au mole fraction (see Figure 2), the core-shell structured NP spectra exhibit two plasmonic peaks corresponding to two LSPR modes. The first mode, from left to right, is higher in energy with a peak near the LSPR peak of a pure Ag NP, and the second mode is lower in energy with a peak near that of a pure Au NP. As the Au shell thickness increases, the intensity of the first peak decreases and broadens until it is no longer distinguishable. Conversely, the peak corresponding to the second mode, lower energy mode, increases in intensity and red shifts slightly with increasing Au shell thickness. A previous study by Bruzzone et al. also used Mie theory and compared the far field (Qext) and near field spectra of Ag-Au core shell particles to the spectra of Ag/Au alloyed NPs of corresponding sizes. In their study, they used a linear combination of the refractive indices of Ag and Au to approximate the refractive indices of the alloys.39 From their results, they inferred that the plasmon resonances of Ag-Au core-shell NPs and corresponding Ag/Au alloyed NPs were very close. Based on the reported experimental spectra and our calculations, their conclusion is clearly invalid.52 In fact, the differences in the extinction spectra of Ag/Au alloyed NPs and Ag-Au core-shell NPs are such that one could use the extinction spectra to determine if synthesized NPs are core-shell structures or alloyed NPs. The core-shell structured NPs will most likely have broad extinction spectra containing two plasmonic peaks. The spectra of alloyed NPs will have only a single narrow plasmonic peak. Additionally, we note that the extinction spectra of Ag-Au core-shell structured NPs differ greatly from the spectra of silica-Au core-shell structured NPs.23 For NPs consisting of a silica core and a thin Au shell, the plasmonic peak is red shifted significantly relative to that of solid Au NPs. For Ag-Au core-shell NPs, however, the plasmonic peaks are between those of pure Ag and pure Au NPs. This difference is due to the strong plasmonic properties of the Ag core in contrast to a silica core, as discussed in our recent paper.27 The dielectric function of Ag has a large imaginary component that dampens the plasmonic properties of the NP compared with a silica core NP.

FIG. 4.

Calculated extinction spectra of Ag-Au core-shell NPs with Au shell thicknesses ranging from 2.5 nm to 10 nm and 30 nm Ag core.

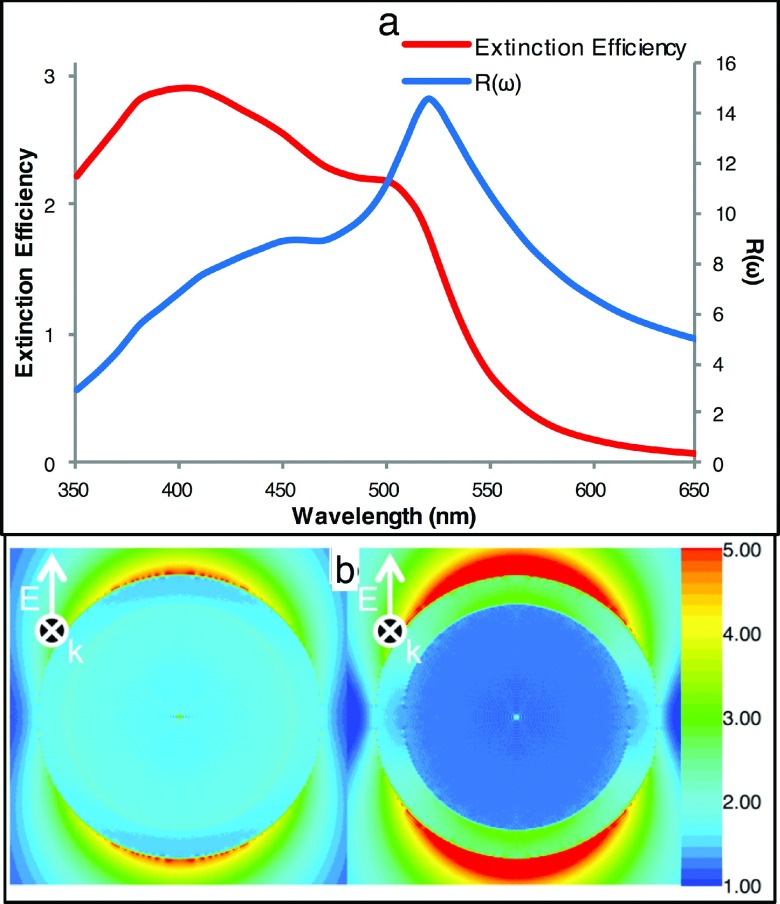

As alluded to previously, the E-field enhancement, R(ω), spectra differ from the far-field extinction efficiency spectra for alloyed NPs. The maximum R(ω) value is red-shifted compared with the peak maximum of the extinction spectrum (see Figure 2(e)) for an Ag/Au alloyed NP. This difference is also significant in the case of a core-shell structured NP. Figure 5(a) plots the extinction spectrum and R(ω) for an Ag-Au core-shell NP together for comparison. According to the hybridization model proposed by Prodan et al., the surface plasmons formed at the two dielectric interfaces present in a core-shell structured NP can hybridize to form a higher energy, asymmetrically coupled mode and a lower energy symmetrically coupled mode.29 For this Ag-Au NP, the asymmetrically coupled mode (∼420 nm, left) absorbs light more strongly than the symmetrically couple mode (∼520 nm, right). However, symmetric coupling of the two surface plasmons results in greater E-field enhancement at the NP surface. Plots of the local E-fields in and around the NP (Figure 5(b)), calculated using the DDA method, illustrate these two modes. From Figure 5, it is evident that the calculation of the far-field extinction spectrum alone does not provide always an accurate estimation of a NP’s E-field enhancement. To accurately determine a NP’s relative SERS properties, calculation of the E-field EF R(ω) spectrum is necessary.

FIG. 5.

(a) Extinction efficiency (primary y-axis) and R(ωi) (secondary y-axis) for an Ag-Au core-shell NP with a 30 nm Ag-core and a 5 nm Au-shell, (b) E-field maps at 420 nm (left) and 520 nm (right).

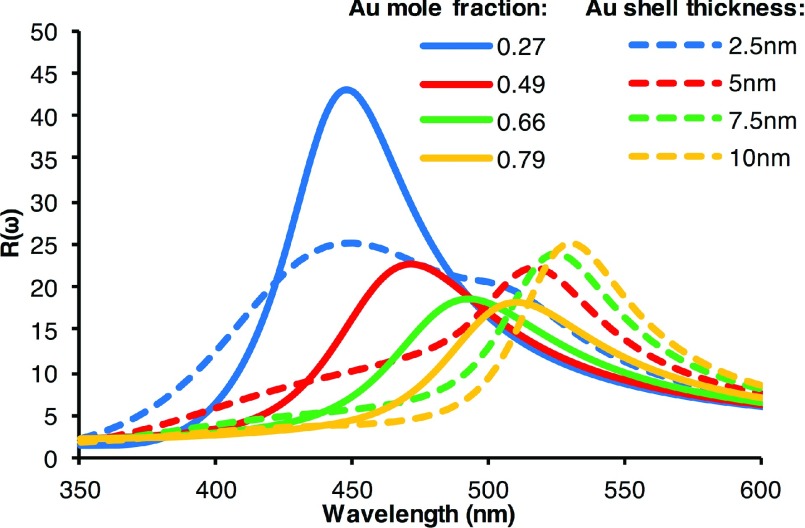

According to Gao et al., core-shell structured NPs can be converted to alloyed NPs by annealing the particles at high temperature.43 Therefore, it would be of interest to compare the E-field EFs of Ag-Au core-shell structured NPs with those of similarly sized Ag/Au alloyed NPs of the same chemical composition. For this comparison, the Au mole fractions of Ag-Au core-shell structured NPs were calculated by assuming bulk densities of Ag and Au in the core and shell, respectively. Figure 6 presents the comparison of electric field enhancement factor R(ω) of both core-shell structured NPs and the corresponding alloyed NPs of the same composition. The comparison reveals several interesting features about the SERS enhancement expected from core-shell structured NPs versus alloyed NPs. We see that for laser excitation wavelengths between 420 nm and 500 nm, Ag/Au alloyed NPs have stronger E-field enhancements than the corresponding core-shell structured NPs. The E-field EFs, R(ω), for the alloy NP with an Au mole fraction of 0.27 have a larger maximum EF than the corresponding core-shell structured NP. Within this same laser excitation window, Ag/Au alloyed NPs offer better SERS enhancements than pure Ag or pure Au NPs (see Figure 3(a)). This indicates that, for incident laser wavelengths between ∼420 nm and ∼500 nm, Ag/Au alloyed NPs would provide better SERS enhancements than core-shell structured NPs, pure Ag NPs, or pure Au NPs. However, for laser excitation wavelengths above 500 nm, the Ag-Au core-shell structured NPs provide better SERS enhancements than the corresponding alloy NPs.

FIG. 6.

Wavelength-dependent E-field EFs of Ag-Au core-shell NPs with Au shell thicknesses ranging from 2.5 nm to 10 nm with Ag cores (dashed) and corresponding Ag/Au alloyed NPs (solid). The total size of NP is fixed at 50 nm while the shell thickness is varied.

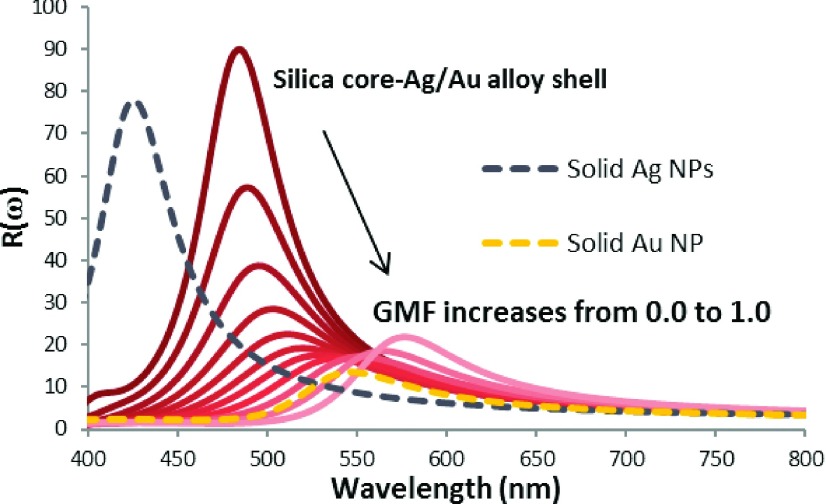

C. Silica-Ag/Au alloy core-shell structured NPs

The plasmonic peaks of NPs with silica-cores and thin Au shells are red-shifted relative to solid Au NPs with the extent of the red shift determined by the shell thickness with respect to the core size.23 The thinner the Au shell, the larger the red-shift. This property has been utilized by the Halas group for nanoshell based photothermal therapy.64 Because the Ag/Au alloy NPs have LSPR peaks that shift from the LSPR peak of a pure Ag NP to that of pure Au NP with increasing Au mole fraction, an Ag/Au alloy shell deposited on a silica core can allow for the tuning of the NPs LSPR peaks by adjusting both the Au mole fraction and the alloy shell thickness. Figure 7 presents the E-field EFs, R(ω), of silica-Ag/Au alloy core-shell NPs with 30 nm silica cores and 10 nm Ag/Au alloy shells. The E-field EFs of solid (no silica core) Ag NPs and solid Au NPs of the same size are included for comparison. We see that the R(ω) of alloy shell NPs is red-shifted relative to those of the solid Ag NPs and solid Au NPs. The maximum enhancement factors of the alloy shell NPs are larger than for both the solid Au NPs and solid Ag NPs. Hence, we believe this Ag/Au hybrid NP design may be of great interest for future SERS detection methods.

FIG. 7.

Wavelength-dependent E-field EFs, R(ω), of silica core-Ag/Au alloy shell NPs with gold mole fractions (GMF) varied from 0.0 to 1.0 (solid lines) with those of pure Ag NPs and pure Au NPs (two dashed lines). The total NP size is fixed at 50 nm. For the core-shell structured NPs, the silica core is 30 nm and the Ag/Au alloy shell thickness is 10 nm.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we have calculated both the extinction and E-field EF R(ω) spectra of Ag/Au hybrid NPs in order to develop a better understanding of the SERS enhancement properties of Ag/Au hybrid NPs. We have shown that the extinction spectra of Ag/Au alloyed NPs calculated using the Mie theory and the dielectric functions of Rioux et al.52 correlate well with the reported experimental spectra. The extinction spectra of Ag/Au alloy NPs exhibit a single plasmonic peak that red shifts as the Au mole fraction increases, a trend that is in agreement with past observations.37 The E-field EF spectra have a similar dependence on chemical composition, but the maxima of these spectra are red-shifted relative to the maxima of the extinction spectra. We have further shown that, for incident wavelengths between ∼420 nm and ∼520 nm, Ag/Au alloyed NPs provide stronger SERS enhancements than pure Ag or pure Au NPs. Additionally, within this range of incident laser wavelengths, the SERS enhancements of Ag/Au alloyed NPs are stronger than those of corresponding Ag-Au core-shell structured NPs. However, for incident laser wavelength above 500 nm, Ag-Au core-shell structured NPs will provide better enhancement than Ag/Au alloyed NPs. Finally, we have shown that silica core and Ag/Au alloy shell structured NPs have larger E-field EFs than pure Ag/Au alloy NPs, pure Ag NPs, and pure Au NPs. Hence, Ag/Au alloy shell deposited on silica core NPs should be of great interest to pursue experimentally.

Acknowledgments

We thank the financial support of the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institutes (Grant No. R15 CA 195509-01), National Science Foundation Tennessee EPSCOR funding (TN-SCORE) (Grant No. EPS-1004083) and NIH/NIGMS No. R15 GM106326-01A.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jain P. K., Huang X., El-Sayed I. H., and El-Sayed M. A., Acc. Chem. Res. , 1578 (2008). 10.1021/ar7002804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halas N. J., Lal S., Chang W.-S., Link S., and Nordlander P., Chem. Rev. , 3913 (2011). 10.1021/cr200061k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim J.-H., Kim J.-S., Choi H., Lee S.-M., Jun B.-H., Yu K.-N., Kuk E., Kim Y.-K., Jeong D. H., Cho M.-H., and Lee Y.-S., Anal. Chem. , 6967 (2006). 10.1021/ac0607663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuenya B. R., Thin Solid Films , 3127 (2010). 10.1016/j.tsf.2010.01.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boisselier E. and Astruc D., Chem. Soc. Rev. , 1759 (2009). 10.1039/b806051g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sau T. K., Rogach A. L., Jäckel F., Klar T. A., and Feldmann J., Adv. Mater. , 1805 (2010). 10.1002/adma.200902557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dreaden E. C., Alkilany A. M., Huang X., Murphy C. J., and El-Sayed M. A., Chem. Soc. Rev. , 2740 (2012). 10.1039/C1CS15237H [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhana S., Lin G., Wang L., Starring H., Mishra S. R., Liu G., and Huang X., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces , 11637 (2015). 10.1021/acsami.5b02741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhana S., Wang Y., and Huang X., Nanomedicine , 1973 (2015). 10.2217/nnm.15.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhana S., Chaffin E., Wang Y., Mishra S. R., and Huang X., Nanomedicine , 593 (2014). 10.2217/nnm.13.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleischmann M., Hendra P. J., and McQuillan A. J., Chem. Phys. Lett. , 163 (1974). 10.1016/0009-2614(74)85388-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeanmaire D. L. and Van Duyne R. P., J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. , 1 (1977). 10.1016/S0022-0728(77)80224-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albrecht M. G. and Creighton J. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. , 5215 (1977). 10.1021/ja00457a071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kneipp K., Wang Y., Kneipp H., Perelman L., Itzkan I., Dasari R., and Feld M., Phys. Rev. Lett. , 1667 (1997). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.1667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kneipp K., Kneipp H., Itzkan I., Dasari R. R., and Feld M. S., J. Phys.: Condens. Matter , R597 (2002). 10.1088/0953-8984/14/18/202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nie S., Science (5303), 1102 (1997). 10.1126/science.275.5303.1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schatz G. C., Young M. A., and Van Duyne R. P., Top. Appl. Phys. , 19 (2006). 10.1007/3-540-33567-6_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moskovits M., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. , 5301 (2013). 10.1039/c2cp44030j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerker M., The Scattering of Light and Other Electromagnetic Radiation (Academic Press, New York, USA, 1969). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papavassiliou G., Prog. Solid State Chem. , 185 (1979). 10.1016/0079-6786(79)90001-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bohren C. F. and Huffman D. R., Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles (Wiley-VCH, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayer K. M. and Hafner J. H., Chem. Rev. , 3828 (2011). 10.1021/cr100313v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain P. K., Lee K. S., El-Sayed I. H., and El-Sayed M. A., J. Phys. Chem. B , 7238 (2006). 10.1021/jp057170o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain P. K. and El-Sayed M. A., Nano Lett. , 2854 (2007). 10.1021/nl071496m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hooshmand N., Jain P. K., and El-Sayed M. A., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. , 374 (2011). 10.1021/jz200034j [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oldenburg S., Averitt R., Westcott S., and Halas N., Chem. Phys. Lett. , 243 (1998). 10.1016/S0009-2614(98)00277-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaffin E. A., Bhana S., O’Connor R. T., Huang X., and Wang Y., J. Phys. Chem. B , 14076 (2014). 10.1021/jp505202k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brullot W., Valev V. K., and Verbiest T., Nanomedicine , 559 (2012). 10.1016/j.nano.2011.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prodan E., Radloff C., Halas N. J., and Nordlander P., Science , 419 (2003). 10.1126/science.1089171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prodan E., Nordlander P., and Halas N. J., Chem. Phys. Lett. , 94 (2003). 10.1016/S0009-2614(02)01828-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeman E. J. and Schatz G. C., J. Phys. Chem. , 634 (1987). 10.1021/j100287a028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bar-Ilan O., Albrecht R. M., Fako V. E., and Furgeson D. Y., Small , 1897 (2009). 10.1002/smll.200801716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Homola J., Yee S. S., and Gauglitz G., Sens. Actuators, B , 3 (1999). 10.1016/S0925-4005(98)00321-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greulich C., Kittler S., Epple M., Muhr G., and Köller M., Langenbecks Arch. Surg. , 495 (2009). 10.1007/s00423-009-0472-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pauksch L., Hartmann S., Rohnke M., Szalay G., Alt V., Schnettler R., and Lips K. S., Acta Biomater. , 439 (2014). 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schrand A. M., Braydich-Stolle L. K., Schlager J. J., Dai L., and Hussain S. M., Nanotechnology , 235104 (2008). 10.1088/0957-4484/19/23/235104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Link S., Wang Z. L., and El-Sayed M. A., J. Phys. Chem. B , 3529 (1999). 10.1021/jp990387w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee K.-S. and El-Sayed M. A., J. Phys. Chem. B , 19220 (2006). 10.1021/jp062536y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruzzone S., Malvaldi M., Arrighini G. P., and Guidotti C., Mater. Sci. Eng. C , 1015 (2007). 10.1016/j.msec.2006.09.047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alqudami A., Annapoorni S., Govind , and Shivaprasad S. M., J. Nanopart. Res. , 1027 (2008). 10.1007/s11051-007-9333-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang L., Chen G., Wang J., Wang T., Li M., and Liu J., J. Mater. Chem. , 6849 (2009). 10.1039/b909600k [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Güzel R., Ustündağ Z., Ekşi H., Keskin S., Taner B., Durgun Z. G., Turan A. A. I., and Solak A. O., J. Colloid Interface Sci. , 35 (2010). 10.1016/j.jcis.2010.07.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao C., Hu Y., Wang M., Chi M., and Yin Y., J. Am. Chem. Soc. , 7474 (2014). 10.1021/ja502890c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fan M., Lai F.-J., Chou H., Lu W., Hwang B.-J., and Brolo A. G., Chem. Sci. , 509 (2013). 10.1039/C2SC21191B [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li J.-M., Yang Y., and Qin D., J. Mater. Chem. C , 9934 (2014). 10.1039/C4TC02004A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y., Pedireddy S., Lee Y. H., Hegde R. S., Tjiu W. W., Cui Y., and Ling X. Y., Small , 4940 (2014). 10.1002/smll.201401242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karam T. E., Smith H. T., and Haber L. H., J. Phys. Chem. C , 18573 (2015). 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b05110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bhatia P., Consiglio J., Diniz J., Lu J. E., Hoff C., Ritz-Schubert S., and Terrill R. H., J. Spectrosc. , 1. 10.1155/2015/676748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olson T. Y., Schwartzberg A. M., Orme C. A., Talley C. E., O’Connell B., and Zhang J. Z., J. Phys. Chem. C , 6319 (2008). 10.1021/jp7116714 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Román-Velázquez C. E., Noguez C., and Zhang J. Z., J. Phys. Chem. A , 4068 (2009). 10.1021/jp810422r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Papavassiliou G. C., J. Phys. F: Met. Phys. , L103 (1976). 10.1088/0305-4608/6/4/004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rioux D., Vallières S., Besner S., Muñoz P., Mazur E., and Meunier M., Adv. Opt. Mater. , 176 (2014). 10.1002/adom.201300457 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mie G., Ann. Phys. , 377 (1908). 10.1002/andp.19083300302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fenn R. W. and Oser H., Appl. Opt. , 1504 (1965). 10.1364/AO.4.001504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Toon O. B. and Ackerman T. P., Appl. Opt. , 3657 (1981). 10.1364/AO.20.003657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bhandari R., Appl. Opt. , 1960 (1985). 10.1364/AO.24.001960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu Z. S. and Wang Y. P., Radio Sci. , 1393, doi:10.1029/91RS01192 (1991). 10.1029/91RS01192 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang W., Appl. Opt. , 1710 (2003). 10.1364/AO.42.001710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Messinger B. J., von Raben K. U., Chang R. K., and Barber P. W., Phys. Rev. B , 649 (1981). 10.1103/PhysRevB.24.649 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Draine B. T. and Flatau P. J., J. Opt. Soc. Am. A , 1491 (1994). 10.1364/JOSAA.11.001491 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Draine B. T. and Flatau P. J., J. Opt. Soc. Am. A , 2693 (2008). 10.1364/JOSAA.25.002693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flatau P. J. and Draine B. T., Opt. Express , 1247 (2012). 10.1364/OE.20.001247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gutkowicz-Krusin D. and Draine B. T., “Propagation of electromagnetic waves on a rectangular lattice of polarizable points,” Astrophysicse-print arXiv:astro-ph/0403082. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lal S., Clare S. E., and Halas N. J., Acc. Chem. Res. , 1842 (2008). 10.1021/ar800150g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]