Abstract

The reactive dicarbonyl metabolite methylglyoxal (MG) is the precursor of the major quantitative advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) in physiological systems - arginine-derived hydroimidazolones and deoxyguanosine-derived imidazopurinones. The glyoxalase system in the cytoplasm of cells provides the primary defence against dicarbonyl glycation by catalysing the metabolism of MG and related reactive dicarbonyls. Dicarbonyl stress is the abnormal accumulation of dicarbonyl metabolites leading to increased protein and DNA modification contributing to cell and tissue dysfunction in ageing and disease. It is produced endogenously by increased formation and/or decreased metabolism of dicarbonyl metabolites. Dicarbonyl stress contributes to ageing, disease and activity of cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents. It contributes to ageing through age-related decline in glyoxalase 1 (Glo-1) activity. Glo-1 has a dual role in cancer as a tumour suppressor protein prior to tumour development and mediator of multi-drug resistance in cancer treatment, implicating dicarbonyl glycation of DNA in carcinogenesis and dicarbonyl-driven cytotoxicity in mechanism of action of anticancer drugs. Glo-1 is a driver of cardiovascular disease, likely through dicarbonyl stress-driven dyslipidemia and vascular cell dysfunction. Dicarbonyl stress is also a contributing mediator of obesity and vascular complications of diabetes. There are also emerging roles in neurological disorders. Glo-1 responds to dicarbonyl stress to enhance cytoprotection at the transcriptional level through stress-responsive increase of Glo-1 expression. Small molecule Glo-1 inducers are in clinical development for improved metabolic, vascular and renal health and Glo-1 inhibitors in preclinical development for multidrug resistant cancer chemotherapy.

Keywords: Methylglyoxal; Glycation; Glyoxalase; Obesity; Diabetes, cancer; Renal failure; Cardiovascular disease; Therapeutics

Dicarbonyl stress and the glyoxalase system

Dicarbonyl stress is the abnormal accumulation of dicarbonyl metabolites leading to increased modification of protein and DNA contributing to cell and tissue dysfunction in ageing and disease [1]. Highly reactive dicarbonyl metabolites often mediating dicarbonyl stress in physiological systems are methylglyoxal (MG), glyoxal, 3-deoxyglucosone (3-DG) and others. The glyoxalase system is a cytoplasm enzymatic pathway, which metabolises the most highly reactive acyclic dicarbonyls – mainly MG and glyoxal. It thereby plays a major role in suppressing dicarbonyl stress in physiological systems, keeping dicarbonyl metabolites at low, tolerable levels. Typical concentrations of glyoxal and MG are 50–150 nM in human plasma and 1–4 μM in plant and mammalian cells [2–4]. When dicarbonyl concentrations increase beyond this there is potential for protein and cell dysfunction leading to impaired health and disease. Examples of dicarbonyl stress are the increased MG in ageing plants [2], increased MG-protein modification in ageing human lens [5], increased plasma and tissue concentration of MG in diabetes [6], and increased concentrations of MG and glyoxal in renal failure [4]. Dicarbonyl stress is caused by an imbalance of the formation and metabolism of dicarbonyl metabolites and also by increased exposure to exogenous dicarbonyls – Fig. 1a. In this review there is a particular but not exclusive focus on MG as it is a major contributor to dicarbonyl stress in physiological systems. Other recent reviews focussing mostly on dicarbonyl stress in obesity and diabetes have been given elsewhere [7, 8].

Fig. 1.

Biochemistry of dicarbonyl stress. a Metabolism of MG by the glyoxalase system. b Formation of hydroimidazolone MG-H1 from arginine residues. c Formation of imidazopurinone MGdG in DNA. Adduct residue is shown with guanyl base only

Formation of methylglyoxal

In mammalian metabolism, MG is formed at relatively high flux mainly by the trace level degradation of triosephosphates, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GA3P) and dihydroxyacetonephosphate (DHAP) - 0.05 – 0.1 % of flux. GA3P was ca. 8-fold more reactive than DHAP in degrading to MG but as the concentration ratio of DHAP/GA3P in cells in situ is ca. 9 or similar [9], both of these triosephosphates are important sources of MG formation in physiological systems in situ [10]. MG formation is a minor fate of triosephosphates: early studies with red blood cells suggested only 0.089 % glucotriose (2 x glucose consumption) was converted to MG [11] and our subsequent studies with endothelial cells and fibroblasts suggest a similar flux. The rate of total cellular formation of MG was estimated to be ca. 125 μmol/kg cell mass per day [11], which for an adult human of 70 kg body mass and 25 kg body cell mass [12] equates to a predicted whole body rate of formation of ca. 3 mmol MG per day (or ca. 3 mg/kg body weight/day). MG is also formed by the oxidation of acetone catalysed by cytochrome P450 2E1 in the catabolism of ketone bodies [13] – which is low except where ketone bodies are increased as in diabetic ketoacidosis, prolonged (>3 days) fasting or low calorie diet [13–15]. MG may also be formed from the oxidation of aminoacetone by semicarbazide amine oxidase (SSAO) in the catabolism of threonine [16]. Recent estimates of the concentration and rates of metabolism of aminoacetone in the presence and absence of SSAO inhibitor suggest this pathway has a flux of ca. 0.1 mmol MG per day in human subjects [17] or ca. 3 % of total MG formation. Vascular adhesion protein-1 is considered the origin of SSAO activity in mammals in vivo [18]. It is found in plasma, endothelium, adipose tissue and smooth muscle and increases ca. 2-fold in congestive heart failure, diabetes and inflammatory liver diseases [19], and may relatedly increase MG formation in these conditions. MG is also formed by the degradation of proteins glycated by glucose and the degradation of monosaccharides [20]. Under physiological conditions with low level phosphate and chelation of trace metal ion, the predicted flux of MG formation from glycated protein degradation is ca. 0.2 mmol MG per day or ca. 7 % of total MG formation. Dietary contributions to MG exposure from food are normally relatively low: sweetened soft drink, 330 ml – 0.1 μmol MG [21], fruit juice, 330 ml – 0.7 μmol, bread/cakes, 100 g, 1–2 μmol and other foodstuffs [22]; that is, combined likely <0.03 mmol MG per day or <1 % MG exposure. MG in foodstuffs was also metabolised and/or reacted with proteins before absorption in the gastrointestinal tract and imposed dicarbonyl stress mainly in the gastrointestinal lumen [23]. The diet may contribute markedly greater to total exposure for other dicarbonyls where culinary heating is a source of formation; for example, 3-DG [24]. Sources of formation of MG and routes of metabolism are summarised in Fig. 2.

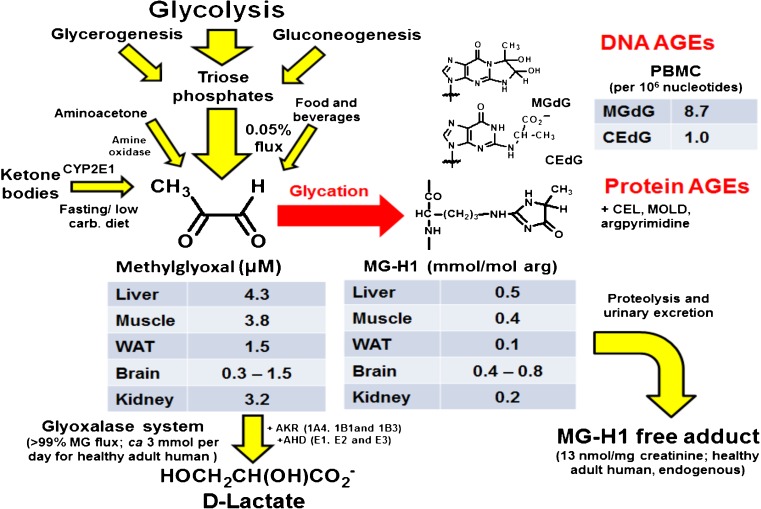

Fig. 2.

Formation of methylglyoxal, metabolism and glycation of protein and DNA in vivo. Tissue levels of MG and MG-H1 adduct residues in tissues are given for mice. PBMC DNA AGEs are for human subjects and flux of MG metabolised by the glyoxalase system and urinary excretion of MG-H1 free adduct is for healthy adduct humans. Data from [2, 63, 89, 122, 137] and Masania, J, Shafie, A, Rabbani, N and Thornalley, P.J., Unpublished observations

Dicarbonyl metabolism by the glyoxalase system

Glyoxal and MG are metabolised mainly by glyoxalase 1 (Glo-1) of the glutathione-dependent glyoxalase system, with minor metabolism by aldoketo reductases (AKRs) and aldehyde dehydrogenases (ADHs). As total MG-derived glycation adducts excreted in urine of healthy human subjects was typically ca. 10 μmol per day [25, 26], it can be inferred that less than 1 % MG formed endogenously modifies the proteins. Most of the MG formed (>99 %) is metabolised by glyoxalase 1 (Glo-1) and aldoketo reductase (AKR) isozymes, which thereby constitute an enzymatic defence against MG glycation. From studies of the level of expression of Glo-1 and AKRs [27, 28], it can be inferred that Glo-1 activity in situ exceeds that of AKR activity for MG metabolism by >30-fold in all human tissues except the renal medulla where the expression of AKR is extraordinarily high. Indeed, Glo-1 is a highly efficient and high abundance enzyme; typically 0.02 % of total protein [27] and is in the top 13 % of proteins by abundance in human cells [29]. In principle, ADHs may also metabolise glyoxal and MG to glyoxylate and pyruvate, respectively. In examination of ADH-linked MG dehydrogenase activity in human cells to date we have found very low or undetectable activity. AKRs and ADH catalyse the metabolism of 3-DG whereas Glo-1 does not [4, 30]. Other proteins, “glyoxalase III” and DJ1, were proposed as glyoxalases but their low catalytic efficiency and cellular content suggests this is unlikely [31].

Basal and inducible expression of Glo-1, AKRs and ADH are under stress-responsive control by nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2) through regulatory antioxidant response elements (AREs) [32–36]. The cytoprotective function of Nrf2 therefore involves enhancing basal and inducible expression and activities of enzymes of dicarbonyl metabolism and thereby prevention of dicarbonyl stress [32]. Other regulatory elements in the mammalian GLO-1 gene are: metal response element, insulin response element, early gene 2 factor-isoform-4, and activating enhancer binding protein-2α, as reviewed [31]. Glo-1 expression is negatively regulated by hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF1α) in hypoxia [37] and also by the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) [31]. Hypoxia may be an important physiological driver of dicarbonyl stress as it both increases MG formation by flux through anaerobic glycolysis and likely decreases Glo-1 expression through activation of HIF1α.

Glo-1 expression is also increased by copy number variation (CNV) of the GLO-1 gene in human and mouse genomes. Human GLO-1 is located in chromosome 6 at locus 6p21.2 [38] and mouse Glo-1 in chromosome 17 at locus 17 a3.3 [39]. Gene cloning and bioinformatics analysis showed that human GLO-1 coding regions consists of 12 kb with introns separating six exons [40, 41]. CNV of human GLO-1 was detected by Redon et al. with a prevalence of ca. 2 %. [42]. Murine Glo-1 CNV was found in inbred strains of mice which included complete copies of Glo-1 and complete and partial copies of other genes [43, 44], giving rise to a 2–4-fold increase in Glo-1 expression. GLO-1 duplication appeared linked to anxiety-like behaviour in mice but may rather be due to a proximate genetic locus co-duplicated with Glo-1 [45].

At in situ concentrations of MG, GSH and Glo-1, the formation and fragmentation of the hemithioacetal of MG and GSH are rapid compared to the Glo-1-catalysed step [31]. A consequence of this is that in situ activity of Glo-1 is directly proportional to GSH concentration. So cellular GSH concentration is an influential factor on in situ activity of Glo-1 and oxidative or non-oxidative depletion of GSH leads to increased glyoxal and MG [46]. The concentration of S-D-lactoylglutathione (SLG) is also maintained at low levels. This is likely so that lactoyl-transfer to protein thiol groups and related inactivation of enzymes with functional cysteinyl thiols is prevented [31]. SLG is also toxic if it leaks out of cells and is metabolised by γ-glutamyl transferase and dipeptidase with rearrangement to N-lactoylcysteine which is an inhibitor of pyrimidine synthesis [47]. A mathematical model of the glyoxalase pathway predicted very low levels of MG and SLG in cells which fitted well with experimental observation [31].

The likely evolutionary pressure for development of Glo-1 was to evolve an enzyme that accepts the major solution species of MG, the MG-GSH hemithioacetal, which is also highly efficient with kcat/KM at the diffusion limit. Glo-1 is thereby exquisitely suited to its function. High reactivity of arginine and cysteine residues in Glo-1 protein could be a problem for Glo-1 stability which would occur with relatively low microscopic pKa. Our computations of microscopic pKa values (as previously described [48]) indicates functionally important R37, R122 and C139 of human Glo-1 have high microscopic pKa values (>12), which confers low reactivity towards MG. Also in cells with 1–4 μM MG, there is a pool of ca. 20 mM cysteinyl thiol groups and ca. 80 mM arginine residues to which MG may bind and only 2 μM and 4 μM of these, respectively, are functionally important residues of Glo-1 [27]. Therefore, Glo-1 is very resistant to inactivation in situ by MG.

Biochemical consequences of dicarbonyl stress

Dicarbonyl stress produces increased in situ rates of glycation by dicarbonyls of proteins, DNA and basic phospholipids. Reaction with proteins is directed to arginine residues forming dihydroxyimidazolidine and hydroimidazolone adducts. The hydroimidazolone derived from MG, MG-H1, is one of the most quantitatively and functionally important AGEs in physiological systems – Fig. 1b. There are also minor lysine-derived AGEs formed: Nε-carboxymethyl-lysine and Nε(1-carboxyethyl)lysine formed from glyoxal and MG, respectively, and others. The major source of CML formation, however, is the oxidative degradation of Nε-fructosyl-lysine residues [49].

Dicarbonyl glycation is particularly insidious as it is directed to arginine – the amino acid residue with highest probability of location in functional sites of proteins, modification induces loss of charge of the side chain guanidino group and functionally important arginine residues tend to be those most reactive towards dicarbonyl glycation [50]. The extent of glycation of proteins by dicarbonyls is low, usually 1–5 %, but may increase in ageing and disease. Proteins modified by glyoxal and MG in dicarbonyl stress are recognised as mis-folded and directed to the proteasome for proteolysis. In yeast an unfocussed gene deletion analysis showed strains deleted for genes of ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation were sensitive to glyoxal and MG toxicity [51]. Examples of physiological dysfunction mediated by dicarbonyl glycation of arginine residues of proteins are: mitochondrial protein dysfunction and increased formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [52], inflammatory protein expression (RAGE, S100 proteins and high mobility group box-1) [53], mitochondrial pathway activated apoptosis [54] and cell detachment from the extracellular matrix and anoikis [55].

A surprising observation was increased chaperone function of αA-crystallin with very high modification by MG for reversing dithiothreitol- and heat-induced misfolding of proteins [56]. With lower, physiological extent of modification by MG, however, the chaperone function of αA-crystallin was not enhanced further [57].

Early studies of specific proteins modified by MG used antibodies to the trace MG-derived AGE, argpyrimidine. In endothelial cells the heat shock protein-27 (HSP27) was detected as a major MG modified protein [58]. This could not be verified by ultrahigh resolution Orbitrap mass spectrometry with direct examination for MG-modification in tryptic peptides – even when modification of proteins was increased 10-fold in cell lysates [59], suggesting earlier studies suffered interference. Subsequent studies showed recombinant HSP27 was modified by 500 μM – 5 mM MG at multiple sites and MG-modified HSP27 was more protective than unmodified protein against apoptotic cell death [60]. The physiological significance is unclear, however, as recent studies were unable to find evidence of MG modification of HSP27 [59] and increased MG and Glo-1 inhibitors tend to promote rather than suppress apoptosis [61, 62].

Glyoxal and MG are important precursors of DNA adducts in physiological systems: major adducts are imidazopurinones GdG and MGdG – nucleotide AGEs. MGdG was the major nucleotide AGE found physiologically – Fig. 1c. DNA content of MGdG exceeded those of the major DNA oxidative damage adduct, 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine. Increased nucleotide AGEs was associated with DNA strand breaks and mutagenesis [63].

Physiological consequences of dicarbonyl stress

Where dicarbonyl stress occurs there is potential for increased cell dysfunction, detachment from the extracellular matrix and anoikis, and apoptosis. Cell dysfunction is driven by the effects of protein glycation: loss of substrate protein activity – through inactivation and/or increased rate of proteolysis and decreased half-life (unless compensatory increased expression is activated), or by gaining a new and damaging function – for example, low density lipoproteins become small, dense and atherogenic by MG modification [64]. This affects multiple proteins – the dicarbonyl proteome - in different cell and tissue compartments [50]. The effects span multiple compartments by diffusion of increased MG or other dicarbonyl in dicarbonyl stress. MG permeates cell plasma membranes by passive diffusion of the unhydrated form. This is rate limited by MG dehydration, giving a half-life of ~4 min [2]. The half-life of MG for metabolism by the glyoxalase system to D-lactate from in situ rates of D-lactate formation in cells is ca. 10 min with free MG mostly (>95 %) reversibly bound to protein. The rate of irreversible binding to protein in plasma was ca. 3.6 h [65]. This implies that part of the MG formed inside cells leaks out from the site of formation and may diffuse through interstitial fluid into plasma and thereafter permeate back into interstitial fluid and cells of other tissues. Also, MG formed from the degradation of glycated proteins in the extracellular compartment may enter cells for metabolism by Glo-1 and AKRs. The locus of dicarbonyl stress and related pathogenesis linked to MG accumulation is therefore likely particularly sensitive to local decrease of Glo-1 expression and activity. Kinetic considerations of the rate of glycation of protein, similar to those for ROS [66], indicates a diffusion distance of MG of ca. 2–3 cm before irreversible reaction, suggesting that MG has relatively long range and half-life to locate and modify sensitive sites of proteins, often leading to protein inactivation and dysfunction.

Dicarbonyl stress in ageing and disease

Ageing

The link of dicarbonyl stress to ageing was unequivocally established in a functional genomics study of Glo-1 in the nematode C. elegans [52]. Ageing-related decline in renal function was prevented in transgenic rats overexpressing Glo-1 [67]. Intuitively we expect this is due to AGE accumulation in proteins of tissues and body fluids with related protein dysfunction. MG-derived AGEs were increased in human lens with age and this was linked to cataract formation [5, 68] and also in skin but to markedly lower extent [68]. Decreased Glo-1 activity was associated with age-linked impairment of wound healing [69] and increased dicarbonyl stress is associated with several ageing-linked diseases – see below. Glo-1 activity declines with age so there is also increased stress on cell proteolysis and compensatory gene expression to keep AGE-modified proteins to a low tolerable level and provide replacement unmodified proteins. Dicarbonyl stress is likely a feature of proliferative senescence of fibroblasts in culture where Glo-1 expression is decreased and glycolytic flux is increased [70, 71]. It is also likely involved in senescence of plants: dicarbonyl content of broccoli increased with age [2] and MG-H1 was a major AGE in Arabidopsis leaves [72].

Obesity

For many years a genetic linkage of Glo-1 to body weight in mice [73] and of GLO-1 to upper-arm circumference and supra-iliac skinfold thickness in human subjects [74] suggested a role for Glo-1 in obesity. In the mouse overeating model of obesity, leptin mutant (ob/ob) mice, Glo-1 protein was decreased 80 % in the liver [75]. Recent conference reports described increased weight gain on high fat diet (HFD)-fed mouse with through-life expression of GLO-1 siRNA and Glo-1 deficiency, compared to wild-type controls [76], and decreased weight gain in Glo-1 overexpressing transgenic mice [77], suggesting a functional role of Glo-1 and dicarbonyl stress in obesity. HFD-fed wild-type mice had increased MG-H1 content of heart and liver, as judged by immunoassay [78]. Dicarbonyl stress may be a mediator of obesity and insulin resistance and thereby a risk factor for development of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Diabetes and diabetic vascular complications

Hypotheses for the involvement of dicarbonyl stress in disease are most advanced and critically evaluated for involvement in the vascular complications of diabetes. Glo-1 activity is decreased and MG-H1 residue content of proteins is increased in the kidney, retina and nerve of pre-clinical models of microvascular complications of diabetes (nephropathy, retinopathy and neuropathy) [79–83]. Functional genomics studies with Glo-1 deficient mice and Glo-1 overexpressing transgenic mice and preventive intervention such as high dose thiamine and Benfotiamine support increased MG as a risk factor linked to the development of diabetic microvascular complications [79, 84–87]. Dicarbonyl stress is also linked to diabetic cardiovascular disease – see below. Formation of MG is increased in cells with GLUT1 glucose transport incubated in high glucose concentration [11, 88]. Decreased Glo-1 activity synergises with increased MG formation to increase cellular and extracellular MG concentration. MG content of blood samples was increased by up to 5–6 fold in patients with diabetes [6]. Increased MG has been found in diabetic kidney in vivo [89] and vascular endothelial cells in high glucose concentration cultures in vitro [55] – including in mitochondria [90]. In locations where it is difficult to excise tissues without leaking of MG from cells and disrupting extracellular fluid – such as retina and cellular and extracellular compartment of peripheral nerve, evidence of dicarbonyl stress is increased levels of dicarbonyl–derived AGEs [83, 91]. Increased MG concentration and protein content of MG-H1 was not found in liver, skeletal muscle and brain in experimental models of type 1 diabetes [25, 83, 92]. MG-derived AGEs were increased in plasma protein and skin collagen of diabetic patients and were linked to risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications [26, 93–95].

Dicarbonyl stress may also play a role in development of T2DM through promotion of insulin resistance [77, 96] and development of type 1 diabetes through mediation of beta-cell toxicity [97]. Recent studies have found increased levels of MG, glyoxal and 3-DG of subjects with impaired glucose tolerance and patients with T2DM in the fasting state and during an oral glucose tolerance test challenge [98]; plasma and glyoxal levels were ca. 3-fold higher for MG and glyoxal than obtained using the reference assay protocol which control [2].

Chronic renal disease

Experimental models of renal failure, bilateral nephrectomy and bilateral ureteral ligation - models of acute total loss and partial loss of renal function, respectively, were associated with profound dicarbonyl stress. Plasma glyoxal and MG increased 5 and 15 fold within 72 h [99]. Patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD) on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis had increased plasma MG and flux of formation of dicarbonyl-derived AGEs [4, 100]. The cause of dicarbonyl stress is unlikely due to decreased dicarbonyl excretion as there is little in normal health [23], although it is linked to renal function [99]. Decreased Glo-1 expression by hypoxia and inflammation in ESRD [101, 102], hypoxia-induced increased anaerobic glycolysis [103] and decreased disposal of triosephosphates by the reductive pentosephosphate pathway (enzymes of which are inhibited by uremic toxins [104]) leading to increased formation of MG may produce dicarbonyl stress in ESRD. Decreased Glo-1 activity in rare GLO-1 frameshift mutation heterozygote human subjects was associated with decreased glomerular filtration rate [67]. A patient with ESRD and low Glo-1 activity had a high frequency of recurrent cardiovascular disease (CVD) events [105]. Further studies showed a high mortality rate in patients with homozygous GLO-1 419CC mutation - reviewed in [106]. This suggests a link of dicarbonyl stress to development of renal failure and CVD complications of ESRD.

Cardiovascular disease

A recent pre-clinical and clinical integrative genomics study revealed Glo-1 deficiency as a driver of CVD [107]. Chemical inhibition of Glo-1 induced atherosclerosis in apoE deficient mice [108]. MG-derived AGEs in plasma protein have been found to be linked to risk of CVD in diabetes [94, 109]. High levels of MG-H1 and CML were associated with rupture-prone plaques in human carotid endarterectomy, accumulating in macrophages surrounding the necrotic core. The expression of Glo-1 was decreased in ruptured compared with stable plaque segments [110]. However, overexpression of Glo-1 in mice did not affect atherosclerotic lesion size and severity in ApoE−/− mice with or without diabetes [111]. Unexpectedly plasma MG and glyoxal concentration were not decreased in Glo-1 transgenic mice. The reason for this is not clear but dicarbonyls are predominately sourced from metabolism and there was limited increase in Glo-1 activity of the liver in the Glo-1 transgenic mice [112]. Dicarbonyl stress in plasma likely contributes to CVD risk through induction of dyslipidaemia and vascular cell dysfunction. MG modification of LDL induced atherogenic transformation to small, dense LDL with increased affinity for arterial walls through binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans [64]. MG modification of HDL induced re-structuring of the HDL particles, increasing density, decreasing stability and plasma half-life in vivo [113]. Dicarbonyl stress also induces vascular cell dysfunction: silencing of Glo-1 in human aortal endothelial cells changed expression of >400 genes – including increased expression of RAGE and associated ligands [53, 107].

Carcinogenesis, tumour growth and cancer chemotherapy

Dicarbonyl stress has a duality of function in cancer development and treatment. Glo-1 is a tumour suppressor protein and a mediator of multidrug resistance (MDR) in cancer chemotherapy. The tumour suppressor function of Glo-1 was revealed in a genome-wide study in p53 knockout, Ras overexpression model of liver carcinogenesis [114]. This is consistent with mutation arising from of dicarbonyl glycation of DNA sometimes leading to carcinogenesis. There were 14 tumour suppressor genes found and currently Glo-1 is the only one for which a readily available strategy for increased cancer prevention exists – dietary Glo-1 inducers in functional foods. The role of Glo-1 in MDR was revealed in a transcriptome-wide subtraction technique of drug-sensitive and drug-resistant tumour cell lines [115]. Increased Glo-1 expression in tumours may be mediated through GLO-1 amplification [116], and also by mutation and increased transcriptional activity of Nrf2 through ARE-linked up-regulation of Glo-1 transcription [117]. High Glo-1 activity may be permissive for growth with high glycolytic activity and flux of MG formation [63]. MDR tumours are susceptible to cell permeable Glo-1 inhibitors [116, 118].

Other diseases

Following discovery of Glo-1 gene duplication in some strains of mice with an anxiety phenotype [43], a link of Glo-1 to pathologic anxiety was proposed – although the anxiety phenotype was linked to both increased and decreased Glo-1 expression [119, 120]. In attempts to link Glo-1 metabolically to dysfunctional brain metabolism, MG was found to agonise the GABAA receptor in primary cerebellar granule neurons with a median effective concentration EC50 of 10.5 μM and this was proposed as mediator of sedation to explain increased GLO-1 CNV with an anxiety phenotype [121]. MG concentration in mouse brain tissue is ca. 7-fold lower than this [122] and only approached the EC50 value with dosing of 300 mg/kg MG [121] – similar to doses producing acute toxicity [123]. Transgenic mice with 2-fold, 4-fold and 5-fold increased Glo-1 expression had an anxiety phenotype with 4- and 5-fold increased expression but not with 2-fold increased expression [121]. Some inconsistences remain, therefore, and further investigation is required.

Dicarbonyl stress has also been linked to severe schizophrenia through a rare frameshift mutation of GLO-1 [124], synucleinopathies such as Parkinson’s disease in experimental pre-clinical models [122] and Alzheimer’s disease through clinical biomarker studies [125].

Dicarbonyl stress-based therapeutics

Alleviation of dicarbonyl stress by glyoxalase 1 inducers

Initial attempts to alleviate dicarbonyl stress were made through dicarbonyl scavengers and claimed for dicarbonyl scavenging properties of existing drugs in treatments for vascular complications of diabetes. A challenge in the design of dicarbonyl scavengers is to achieve sufficient reactivity for the low concentration of drug achieved clinically with the 1000–10,000 fold higher concentration of arginine residues in tissues and body fluids. Aminoguanidine and phenacylthiazolium bromide showed some promise but their toxicity and instability prohibited further development [4, 126, 127]. Metformin and pyridoxamine are not efficient scavengers of MG and where associated with alleviation of dicarbonyl stress likely function by other mechanisms [128–131]. High dose thiamine supplements for prevention of T2DM and vascular complications of diabetes may work partly by preventing the formation of MG through increased disposal of triosephosphates in the reductive pentosephosphate pathway [132, 133].

A better strategy is development of Glo-1 inducers through activation and binding of Nrf2 to the GLO-1 functional ARE [32]. This offers an alternative that is likely safe and effective. It also addresses a key cause of dicarbonyl stress in disease – disease-associated, tissue-specific deficiency of Glo-1. Detection of Nrf2 activators for ARE-linked induction of Glo-1 expression requires a specific screen with the GLO-1-ARE motif or similar as not all Nrf2 activators induce expression of Glo-1. Nrf2 activators typically change expression of a subset of ARE-linked genes. The basis of this subset selection is unknown but it is likely determined by the level of functionally-active Nrf2 achieved in the cell nucleus in response to the Nrf2 activator, recruitment of relevant accessory proteins – such as small maf proteins [134, 135], and absence of activation of counter-signalling effects required to induce the ARE-linked gene of interest. Nrf2 regulates inducible expression of ca. 890 genes [136]. The advantage of Nrf2 regulated, ARE-regulated genes is that they are a battery of protective genes and so where co-regulated along with Glo-1, they tend to add to the health beneficial response. In this regard, concurrent induction of GSH synthesis for increased cellular GSH concentration to support increased in situ activity of Glo-1 is particularly beneficial [137].

A Glo-1 inducer formulation has been optimised and evaluated in Phase 1 clinical trial (Clinicaltrials.org; NCT02095873) in overweight and obese subjects for safety and target pharmacology at a working dose. We also did functional assessments – Phase 2 A trials for health improvement in obesity. The Glo-1 inducer is a binary combination of trans-resveratrol and hesperetin (tRES-HESP) and was evaluated in a randomised, placebo-controlled crossover clinical trial in 29 overweight and obese subjects. In highly overweight subjects (BMI >27.5 kg/m2), tRES-HESP co-formulation increased expression and activity of Glo-1, decreased plasma methylglyoxal and total body methylglyoxal-protein glycation. It decreased fasting and postprandial plasma glucose, increased oral-glucose-insulin-sensitivity (OGIS) index – an assessment of insulin sensitivity, and improved arterial dilatation. In all subjects, it decreased vascular inflammation marker sICAM-1. In previous clinical evaluations, tRES and HESP individually were ineffective. tRES-HESP co-formulation could be a suitable treatment for improved metabolic and vascular health in overweight and obese populations. It now available for evaluation in Phase 2 clinical trial against disease targets.

This first-in-class Glo-1 inducer trial establishes Glo-1 target pharmacology for tRES-HESP. Whilst increased Glo-1 expression likely contributes to the observed health beneficial effects, changes in other gene expression occurred and their interplay may also mediate the overall health benefit achieved. Nevertheless it was pursuit and optimisation of induction of Glo-1 expression that arrived at this synergistic combination of bioactive compounds and achieved improved metabolic and vascular health in overweight and obese subjects that is unmatched by other therapy. The marked health improvements were achieved with expression of many antioxidant-linked genes unchanged – at least in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells analysed.

Cell permeable Glo-1 inhibitors which increase dicarbonyl stress may find use as anti-tumour and anti-microbial agents for treatment of Glo-1-linked MDR tumours and microbial infections. S-p-Bromobenzylglutathione diethyl ester was the first cell permeable Glo-1 inhibitor developed and had median growth inhibitory concentration GC50 values in the range 7–20 μM for a range of cancer cell lines. Subsequent development of the cyclopentyl ester derivative increased potency and had anti-tumour activity in tumour-bearing mice [62, 138, 139]. A difficulty in clinical translation is identifying tumours that are sensitive to Glo-1 inhibitors. These are likely tumours with a relatively high flux of MG formation and high activity of Glo-1 such that when a Glo-1 inhibitor is delivered into the tumour, MG accumulates rapidly to toxic levels. GLO-1 amplification in tumours is not a reliable marker of this as it is not always functional and does not report on flux of MG. Systems modelling of the glyoxalase pathway is beneficial in assessment of the potency of Glo-1 inducer or Glo-1 inhibitor required to achieve the desired pharmacological and therapeutic effects [31].

Stages of development of therapeutics targeting dicarbonyl stress are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Therapeutic agents in development targeting the glyoxalase system

| Therapeutic class | Mechanism of action | Primary target application (secondary) | Stage of development | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyoxalase 1 inducer | Small molecule Nrf2 activator targeting GLO-1-ARE transcriptional activity | Diabetic nephropathy (other microvascular complications of diabetes; obesity – NAFLD; cardiovascular disease) | Clinical trial Phase 2 ready (Phase 1 complete with safety, dose and pharmacology established). | [137] |

| Glyoxalase 1 inhibitor | Substrate analogue inhibitor diester (prodrug) | Cancer (GLO-1 overexpressing, MDR tumours) | Pre-clinical in vivo models | [62, 118, 140] |

Acknowledgments

With thank research colleagues and collaborators who have contributed to studies covered in this review.

Abbreviations

- ADH

Aldehyde dehydrogenase

- AGE

Advanced glycation endproduct

- AKR

Aldoketo reductase

- ARE

Antioxidant response element

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- 3-DG

3-Deoxyglucosone

- DHAP

Dihydroxyacetonephosphate

- ESRD

End stage renal disease

- GA3P

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

- GdG

3-(2′-deoxyribosyl)-6,7-dihydro-6,7-dihydroxyimidazo-[2,3-b]purin-9(8)one

- Glo-1

Glyoxalase 1

- HFD

High fat diet

- HIF1α

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

- HSP27

Heat shock protein 27

- MDR

Multidrug resistance

- MG

Methylglyoxal

- MGdG

3-(2′-deoxyribosyl)-6,7-dihydro-6,7-dihydroxy-6/7-methylimidazo-[2,3-b]purine-9(8)one

- MG-H1

Nδ-(5-hydro-5-methyl-4-imidazolon-2-yl)-ornithine

- NAFLD

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Nrf2

Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- RAGE

Receptor for advanced glycation endproducts

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SSAO

Semicarbazide amine oxidase

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

References

- 1.Rabbani N, Thornalley PJ. Glyoxalase centennial conference: introduction, history of research on the glyoxalase system and future prospects. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2014;42(2):413–418. doi: 10.1042/BST20140014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabbani N, Thornalley PJ. Measurement of methylglyoxal by stable isotopic dilution analysis LC-MS/MS with corroborative prediction in physiological samples. Nat. Protoc. 2014;9(8):1969–1979. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thornalley PJ, Rabbani N. Assay of methylglyoxal and glyoxal and control of peroxidase interference Biochem. Soc. Transit. 2014;42(2):504–510. doi: 10.1042/BST20140009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabbani, N., Thornalley, P.J.: Dicarbonyls (Glyoxal, Methylglyoxal, and 3-Deoxyglucosone). In: Uremic Toxins. pp. pp. 177–192. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., (2012)

- 5.Ahmed N, Thornalley PJ, Dawczynski J, Franke S, Strobel J, Stein G, Haik GM., Jr Methylglyoxal-derived hydroimidazolone advanced glycation endproducts of human lens proteins. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44(12):5287–5292. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLellan AC, Thornalley PJ, Benn J, Sonksen PH. The glyoxalase system in clinical diabetes mellitus and correlation with diabetic complications. Clin. Sci. 1994;87(1):21–29. doi: 10.1042/cs0870021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matafome P, Sena C, Seiça R. Methylglyoxal, obesity, and diabetes. Endocr. 2013;43(3):472–484. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9795-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maessen DEM, Stehouwer CDA, Schalkwijk CG. The role of methylglyoxal and the glyoxalase system in diabetes and other age-related diseases. Clin. Sci. 2015;128(12):839–861. doi: 10.1042/CS20140683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veech RI, Rajiman L, Dalziel K, Krebs HA. Disequilibrium in the triose phosphate isomerase system. Biochem. J. 1969;115(4):837–842. doi: 10.1042/bj1150837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips SA, Thornalley PJ. The formation of methylglyoxal from triose phosphates. Investigation using a specific assay for methylglyoxal. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;212(1):101–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thornalley PJ. Modification of the glyoxalase system in human red blood cells by glucose in vitro. Biochem.J. 1988;254(3):751–755. doi: 10.1042/bj2540751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis KJ. Human body composition: in vivo methods. Physiol. Rev. 2000;80(2):649–680. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reichard GA, Skutches CL, Hoeldtke RD, Owen OE. Acetone metabolism in humans during diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetes. 1986;35(6):668–674. doi: 10.2337/diab.35.6.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balasse EO. Kinetics of ketone body metabolism in fasting humans. Metabolism. 1979;28(1):41–50. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(79)90166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magee, M.S., Knopp, R.H., Benedetti, T.J.: Metabolic effects of 1200-kcal diet in obese pregnant women with gestational diabetes. Diabetes 39(2), 234–240 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Lyles GA, Chalmers J. The metabolism of aminoacetone to methylglyoxal by semicarbazide- sensitive amino oxidase in human umbilical artery. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1992;43(7):1409–1414. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90196-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kazachkov, M., Yu, P.H.: A novel HPLC procedure for detection and quantification of aminoacetone, a precursor of methylglyoxal, in biological samples. J. Chromatogr. B 824(1–2), 116–122 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Stolen CM, Yegutkin GG, Kurkijärvi R, Bono P, Alitalo K, Jalkanen S. Origins of serum semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase. Circ. Res. 2004;95(1):50–57. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000134630.68877.2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pannecoeck, R., Serruys, D., Benmeridja, L., Delanghe, J.R., Geel, N.v., Speeckaert, R., Speeckaert, M.M.: Vascular adhesion protein-1: Role in human pathology and application as a biomarker. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 52(6), 284–300 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Thornalley PJ, Langborg A, Minhas HS. Formation of glyoxal, methylglyoxal and 3-deoxyglucosone in the glycation of proteins by glucose. Biochem. J. 1999;344(1):109–116. doi: 10.1042/bj3440109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thornalley PJ, Rabbani N. Dicarbonyls in cola drinks sweetened with sucrose or high fructose corn syrup. In: Thomas MC, Forbes J, editors. Maillard reaction: Interface between aging, nutrition and metabolism. London: RSC Publishing; 2010. pp. 158–163. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Degen J, Hellwig M, Henle T. 1,2-dicarbonyl compounds in commonly consumed foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60(28):7071–7079. doi: 10.1021/jf301306g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Degen J, Vogel M, Richter D, Hellwig M, Henle T. Metabolic transit of dietary methylglyoxal. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61(43):10253–10260. doi: 10.1021/jf304946p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Degen J, Beyer H, Heymann B, Hellwig M, Henle T. Dietary influence on urinary excretion of 3-deoxyglucosone and its metabolite 3-Deoxyfructose. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014;62(11):2449–2456. doi: 10.1021/jf405546q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thornalley PJ, Battah S, Ahmed N, Karachalias N, Agalou S, Babaei-Jadidi R, Dawnay A. Quantitative screening of advanced glycation endproducts in cellular and extracellular proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Biochem. J. 2003;375(3):581–592. doi: 10.1042/bj20030763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed N, Babaei-Jadidi R, Howell SK, Beisswenger PJ, Thornalley PJ. Degradation products of proteins damaged by glycation, oxidation and nitration in clinical type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2005;48(8):1590–1603. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1810-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsen K, Aronsson AC, Marmstal E, Mannervik B. Immunological comparison of glyoxalase I from yeast and mammals with quantitative determination of the enzyme in human tissues by radioimmunoassay. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. 1985;82(4):625–638. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(85)90499-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishimura C, Furue M, Ito T, Ohmori Y, Tanimoto T. Quantitative determination of human aldose reductase by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1993;46(1):21–28. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90343-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwanhausser B, Busse D, Li N, Dittmar G, Schuchhardt J, Wolf J, Chen W, Selbach M. Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature. 2011;473(7347):337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collard F, Vertommen D, Fortpied J, Duester G, Van Schaftingen E. Identification of 3-deoxyglucosone dehydrogenase as aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 A1 (retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 1) Biochimie. 2007;89(3):369–373. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rabbani N, Xue M, Thornalley PJ. Activity, regulation, copy number and function in the glyoxalase system. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2014;42(2):419–424. doi: 10.1042/BST20140008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xue M, Rabbani N, Momiji H, Imbasi P, Anwar MM, Kitteringham NR, Park BK, Souma T, Moriguchi T, Yamamoto M, Thornalley PJ. Transcriptional control of glyoxalase 1 by Nrf2 provides a stress responsive defence against dicarbonyl glycation. Biochem. J. 2012;443(1):213–222. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwak MK, Wakabayashi N, Itoh K, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW. Modulation of gene expression by cancer chemopreventive dithiolethiones through the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Identification of novel gene clusters for cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(10):8135–8145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacLeod AK, McMahon M, Plummer SM, Higgins LG, Penning TM, Igarashi K, Hayes JD. Characterization of the cancer chemopreventive NRF2-dependent gene battery in human keratinocytes: demonstration that the KEAP1-NRF2 pathway, and not the BACH1-NRF2 pathway, controls cytoprotection against electrophiles as well as redox-cycling compounds. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(9):1571–1580. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishinaka T, Yabe-Nishimura C. Transcription factor Nrf2 regulates promoter activity of mouse aldose reductase (AKR1B3) Gene. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2005;97(1):43–51. doi: 10.1254/jphs.FP0040404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thimmulappa RK, Mai KH, Srisuma S, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Biswal S. Identification of Nrf2-regulated genes induced by the chemopreventive agent sulforaphane by oligonucleotide array. Cancer Res. 2002;62(18):5196–5203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H, Li H, Xi HS, Li S. HIF1α is required for survival maintenance of chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells. Blood. 2012;119(11):2595–2607. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-387381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tripodis N, Mason R, Humphray SJ, Davies AF, Herberg JA, Trowsdale J, Nizetic D, Senger G, Ragoussis J. Physical Map of Human 6p21.2–6p21.3: Region Flanking the Centromeric End of the Major Histocompatibility Complex. Genome Res. 1998;8(6):631–643. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.6.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meo T, Douglas T, Rijnbeek AM. Glyoxalase-I polymorphism in mouse - new genetic-marker linked to H-2. Science. 1977;198(4314):311–313. doi: 10.1126/science.910130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ranganathan S, Ciaccio PJ, Walsh ES, Tew KD. Genomic sequence of human glyoxalase-I: analysis of promoter activity and its regulation. Gene. 1999;240(1):149–155. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00420-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gale CP, Grant PJ. The characterisation and functional analysis of the human glyoxalase-1 gene using methods of bioinformatics. Gene. 2004;340(2):251–260. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Redon, R., Ishikawa, S., Fitch, K.R., Feuk, L., Perry, G.H., Andrews, T.D., Fiegler, H., Shapero, M.H., Carson, A.R., Chen, W., Cho, E.K., Dallaire, S., Freeman, J.L., Gonzalez, J.R., Gratacos, M., Huang, J., Kalaitzopoulos, D., Komura, D., MacDonald, J.R.1, Marshall, C.R., Mei, R., Montgomery, L., Nishimura, K., Okamura, K., Shen, F., Somerville, M.J., Tchinda, J., Valsesia, A., Woodwark, C., Yang, F., Zhang, J., Zerjal, T., Zhang, J., Armengol, L., Conrad, D.F., Estivill, X., Tyler-Smith, C., Carter, N.P., Aburatani, H., Lee, C., Jones, K.W., Scherer, S.W., Hurles, M.E.: Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature 444(7118), 444–454 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Williams R, Lim JE, Harr B, Wing C, Walters R, Distler MG, Teschke M, Wu C, Wiltshire T, Su AI, Sokoloff G, Tarantino LM, Borevitz JO, Palmer AA. A common and unstable copy number variant is associated with differences in Glo-1 expression and anxiety-like behavior. PLoS One. 2009;4(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cahan P, Li Y, Izumi M, Graubert TA. The impact of copy number variation on local gene expression in mouse hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Nat. Genet. 2009;41(4):430–437. doi: 10.1038/ng.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shafie A, Xue MZ, Thornalley PJ, Rabbani N. Copy number variation of glyoxalase I. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2014;42(2):500–503. doi: 10.1042/BST20140011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abordo EA, Minhas HS, Thornalley PJ. Accumulation of α-oxoaldehydes during oxidative stress. A role in cytotoxicity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;58(4):641–648. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00132-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edwards LG, Adesida A, Thornalley PJ. Inhibition of human leukaemia 60 cell growth by S -D-lactoylglutathione in vitro. Mediation by metabolism to N -D-lactoylcysteine and induction of apoptosis. Leuk. Res. 1996;20:17–26. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(95)00095-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmed N, Dobler D, Dean M, Thornalley PJ. Peptide mapping identifies hotspot site of modification in human serum albumin by methylglyoxal involved in ligand binding and esterase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280(7):5724–5732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rabbani N, Thornalley PJ. Glycation research in amino acids: a place to call home. Amino Acids. 2012;42(4):1087–1096. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0782-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rabbani N, Thornalley PJ. Methylglyoxal, glyoxalase 1 and the dicarbonyl proteome. Amino Acids. 2012;42(4):1133–1142. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0783-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoon, S., Gebbia, M., Costanzo, M., Davis, R.W., Giaever, G., Nislow, C.: A global perspective of the genetic basis for carbonyl stress resistance. G3 (Bethesda, Md.) 1(3) (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Morcos M, Du X, Pfisterer F, Hutter H, Sayed AAR, Thornalley P, Ahmed N, Baynes J, Thorpe S, Kukudov G, Schlotterer A, Bozorgmehr F, El Baki RA, Stern D, Moehrlen F, Ibrahim Y, Oikonomou D, Hamann A, Becker C, Zeier M, Schwenger V, Miftari N, Humpert P, Hammes HP, Buechler M, Bierhaus A, Brownlee M, Nawroth PP. Glyoxalase-1 prevents mitochondrial protein modification and enhances lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2008;7(2):260–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yao D, Brownlee M. Hyperglycemia-induced reactive oxygen species increase expression of RAGE and RAGE ligands. Diabetes. 2009;59(1):249–255. doi: 10.2337/db09-0801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chan WH, Wu HJ, Shiao NH. Apoptotic signaling in methylglyoxal-treated human osteoblasts involves oxidative stress, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, caspase-3, and p21-activated kinase 2. J. Cell. Biochem. 2007;100(4):1056–1069. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dobler D, Ahmed N, Song LJ, Eboigbodin KE, Thornalley PJ. Increased dicarbonyl metabolism in endothelial cells in hyperglycemia induces anoikis and impairs angiogenesis by RGD and GFOGER motif modification. Diabetes. 2006;55(7):1961–1969. doi: 10.2337/db05-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nagaraj RH, Oya-Ito T, Padayatti PS, Kumar R, Mehta S, West K, Levison B, Sun J, Crabb JW, Padival AK. Enhancement of chaperone function of alpha-crystallin by methylglyoxal modification. Biochemistry. 2003;42(36):10746–10755. doi: 10.1021/bi034541n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gangadhariah MH, Wang BL, Linetsky M, Henning C, Spanneberg R, Glomb MA, Nagaraj RH. Hydroimidazolone modification of human alpha A-crystallin: effect on the chaperone function and protein refolding ability. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1802(4):432–441. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schalkwijk CG, van Bezu J, van der Schors RC, Uchida K, Stehouwer CDA, van Hinsbergh VWM. Heat-shock protein 27 is a major methylglyoxal-modified protein in endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(6):1565–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rabbani N, Thornalley PJ. Dicarbonyl proteome and genome damage in metabolic and vascular disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2014;42(2):425–432. doi: 10.1042/BST20140018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oya-Ito T, Naito Y, Takagi T, Handa O, Matsui H, Yamada M, Shima K, Yoshikawa T. Heat-shock protein 27 (Hsp27) as a target of methylglyoxal in gastrointestinal cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1812(7):769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kang Y, Edwards LG, Thornalley PJ. Effect of methylglyoxal on human leukaemia 60 cell growth: modification of DNA, G 1 growth arrest and induction of apoptosis. Leuk. Res. 1996;20:397–405. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(95)00162-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thornalley PJ, Edwards LG, Kang Y, Wyatt C, Davies N, Ladan MJ, Double J. Antitumour activity of S-p- bromobenzylglutathione cyclopentyl diester in vitro and in vivo. Inhibition of glyoxalase I and induction of apoptosis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1996;51(10):1365–1372. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thornalley PJ, Waris S, Fleming T, Santarius T, Larkin SJ, Winklhofer-Roob BM, Stratton MR, Rabbani N. Imidazopurinones are markers of physiological genomic damage linked to DNA instability and glyoxalase 1-associated tumour multidrug resistance. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(16):5432–5442. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rabbani N, Godfrey L, Xue M, Shaheen F, Geoffrion M, Milne R, Thornalley PJ. Conversion of low density lipoprotein to the pro-atherogenic form by methylglyoxal with increased arterial proteoglycan binding and aortal retention. Diabetes. 2011;60(7):1973–1980. doi: 10.2337/db11-0085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thornalley PJ. Dicarbonyl intermediates in the Maillard reaction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005;1043:111–117. doi: 10.1196/annals.1333.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Winterbourn CC. Reconciling the chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4(5):278–286. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ikeda Y, Inagi R, Miyata T, Nagai R, Arai M, Miyashita M, Itokawa M, Fujita T, Nangaku M. Glyoxalase I retards renal senescence. Amer. J. Pathol. 2011;179(6):2810–2821. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fan X, Sell DR, Zhang J, Nemet I, Theves M, Lu J, Strauch C, Halushka MK, Monnier VM. Anaerobic vs aerobic pathways of carbonyl and oxidant stress in human lens and skin during aging and in diabetes: a comparative analysis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;49(5):847–856. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fleming TH, Theilen TM, Masania J, Wunderle M, Karimi J, Vittas S, Bernauer R, Bierhaus A, Rabbani N, Thornalley PJ, Kroll J, Tyedmers J, Nawrotzki R, Herzig S, Brownlee M, Nawroth PP. Aging-dependent reduction in glyoxalase 1 delays wound healing. Gerontology. 2013;59(5):427–437. doi: 10.1159/000351628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ahmed EK, Rogowska-Wrzesinska A, Roepstorff P, Bulteau AL, Friguet B. Protein modification and replicative senescence of WI-38 human embryonic fibroblasts. Aging Cell. 2010;9(2):252–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.James EL, Michalek RD, Pitiyage GN, de Castro AM, Vignola KS, Jones J, Mohney RP, Karoly ED, Prime SS, Parkinson EK. Senescent human fibroblasts show increased glycolysis and redox homeostasis with extracellular metabolomes that overlap with those of irreparable DNA damage, aging, and disease. J. Proteome Res. 2015;14(4):1854–1871. doi: 10.1021/pr501221g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bechtold U, Rabbani N, Mullineaux PM, Thornalley PJ. Quantitative measurement of specific biomarkers for protein oxidation, nitration and glycation in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant J. 2009;59(4):661–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wuschke S, Dahm S, Schmidt C, Joost HG, Al Hasani H. A meta-analysis of quantitative trait loci associated with body weight and adiposity in mice. Int. J. Obes. 2006;31(5):829–841. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wilson AF, Elston RC, Tran LD, Siervogel RM. Use of the robust sib-pair method to screen for single-locus, multiple-locus, and pleiotropic effects: application to traits related to hypertension. Amer J Human Genet. 1991;48(5):862–872. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sanchez JC, Converse V, Nolan A, Schmid G, Wang S, Heller M, Sennitt MV, Hochstrasser DF, Cawthorne MA. Effect of rosiglitazone on the differential expression of diabetes-associated proteins in pancreatic islets of C57BI/6 lep/lep mice. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2002;1(7):509–516. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M200033-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wortmann, M., Hakimi, M., Fleming, T., Peters, A., Nawroth, P., Bockler, D., Dihlmann, S.: The role of glyoxalase-1 (Glo-1) in mouse metabolism and atherosclerosis. Biochem.Soc.Trans., www.biochemistry.org/Portals/0/Conferences/abstracts/SA158/SA158P005.pdf (2013).

- 77.Maessen, D., Brouwers, O., Miyata, T., Stehouwer, C., Schalkwijk, C.: Glyoxalase-1 overexpression reduces body weight and adipokine expression, and improves insulin sensitivity in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Diabetologia 57, Supplement 1, 713 (2014).

- 78.Li SY, Liu Y, Sigmon VK, McCort A, Ren J. High-fat diet enhances visceral advanced glycation end products, nuclear O-Glc-Nac modification, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and apoptosis. Diabetes Obesity & Metabolism. 2005;7(4):448–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2004.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bierhaus A, Fleming T, Stoyanov S, Leffler A, Babes A, Neacsu C, Sauer SK, Eberhardt M, Schnolzer M, Lasischka F, Neuhuber WL, Kichko TI, Konrade I, Elvert R, Mier W, Pirags V, Lukic IK, Morcos M, Dehmer T, Rabbani N, Thornalley PJ, Edelstein D, Nau C, Forbes J, Humpert PM, Schwaninger M, Ziegler D, Stern DM, Cooper ME, Haberkorn U, Brownlee M, Reeh PW, Nawroth PP. Methylglyoxal modification of Nav1.8 facilitates nociceptive neuron firing and causes hyperalgesia in diabetic neuropathy. Nat. Med. 2012;18(6):926–933. doi: 10.1038/nm.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Barati MT, Merchant ML, Kain AB, Jevans AW, McLeish KR, Klein JB. Proteomic analysis defines altered cellular redox pathways and advanced glycation end-product metabolism in glomeruli of db/db diabetic mice. Amer J Physiol - Renal Physiology. 2007;293(4):F1157–F1165. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00411.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Palsamy P, Subramanian S. Resveratrol protects diabetic kidney by attenuating hyperglycemia-mediated oxidative stress and renal inflammatory cytokines via Nrf2/Keap1 signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2011;1812(7):719–731. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Miller AG, Tan G, Binger KJ, Pickering RJ, Thomas MC, Nagaraj RH, Cooper ME, Wilkinson-Berka JL. Candesartan attenuates diabetic retinal vascular pathology by restoring glyoxalase 1 function. Diabetes. 2010;59(12):3208–3215. doi: 10.2337/db10-0552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Karachalias N, Babaei-Jadidi R, Rabbani N, Thornalley PJ. Increased protein damage in renal glomeruli, retina, nerve, plasma and urine and its prevention by thiamine and benfotiamine therapy in a rat model of diabetes. Diabetologia. 2010;53(7):1506–1516. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1722-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Giacco F, Du X, D’Agati VD, Milne R, Sui G, Geoffrion M, Brownlee M. Knockdown of glyoxalase 1 mimics diabetic nephropathy in nondiabetic mice. Diabetes. 2014;63(1):291–299. doi: 10.2337/db13-0316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Berner AK, Brouwers O, Pringle R, Klaassen I, Colhoun L, McVicar C, Brockbank S, Curry JW, Miyata T, Brownlee M, Schlingemann RO, Schalkwijk C, Stitt AW. Protection against methylglyoxal-derived AGEs by regulation of glyoxalase 1 prevents retinal neuroglial and vasodegenerative pathology. Diabetologia. 2012;55(3):845–854. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2393-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Babaei-Jadidi R, Karachalias N, Ahmed N, Battah S, Thornalley PJ. Prevention of incipient diabetic nephropathy by high dose thiamine and benfotiamine. Diabetes. 2003;52(8):2110–2120. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.8.2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hammes HP, Du X, Edelstein D, Taguchi T, Matsumura T, Ju Q, Lin J, Bierhaus A, Nawroth P, Hannak D, Neumaier M, Bergfeld R, Giardino I, Brownlee M. Benfotiamine blocks three major pathways of hyperglycemic damage and prevents experimental diabetic retinopathy. Nat. Med. 2003;9(3):294–299. doi: 10.1038/nm834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shinohara M, Thornalley PJ, Giardino I, Beisswenger PJ, Thorpe SR, Onorato J, Brownlee M. Overexpression of glyoxalase I in bovine endothelial cells inhibits intracellular advanced glycation endproduct formation and prevents hyperglycaemia-induced increases in macromolecular endocytosis. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101(5):1142–1147. doi: 10.1172/JCI119885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Geoffrion M, Du X, Irshad Z, Vanderhyden BC, Courville K, Sui G, D'Agati VD, Ott-Braschi S, Rabbani N, Thornalley PJ, Brownlee M, Milne RW. Differential effects of glyoxalase 1 overexpression on diabetic atherosclerosis and renal dysfunction in streptozotocin-treated, apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Phys. Rep. 2014;2(6) doi: 10.14814/phy2.12043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pun PBL, Logan A, Darley-Usmar V, Chacko B, Johnson MS, Huang GW, Rogatti S, Prime TA, Methner C, Krieg T, Fearnley IM, Larsen L, Larsen DS, Menger KE, Collins Y, James AM, Kumar GDK, Hartley RC, Smith RAJ, Murphy MP. A mitochondria-targeted mass spectrometry probe to detect glyoxals: implications for diabetes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014;67:437–450. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Duran-Jimenez B, Dobler D, Moffatt S, Rabbani N, Streuli CH, Thornalley PJ, Tomlinson DR, Gardiner NJ. Advanced glycation endproducts in extracellular matrix proteins contribute to the failure of sensory nerve regeneration in diabetes. Diabetes. 2009;58:2893–2903. doi: 10.2337/db09-0320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Phillips SA, Mirrlees D, Thornalley PJ. Modification of the glyoxalase system in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Effect of the aldose reductase inhibitor Statil. Biochem.Pharmacol. 1993;46:805–811. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90488-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Genuth S, Sun W, Cleary P, Gao X, Sell DR, Lachin J, Group, t.D.E.R. Monnier VM. Skin Advanced Glycation Endproducts (AGEs) Glucosepane and Methylglyoxal Hydroimidazolone are Independently Associated with Long-term Microvascular Complication Progression of Type I diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64(1):266–278. doi: 10.2337/db14-0215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hanssen NMJ, Beulens JWJ, van Dieren S, Scheijen JLJM, van der A DL, Spijkerman AMW, van der Schouw YT, Stehouwer CDA, Schalkwijk CG. Plasma Advanced Glycation End Products Are Associated With Incident Cardiovascular Events in Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes: A Case-Cohort Study With a Median Follow-up of 10 Years (EPIC-NL). Diabetes. 2015;64(1):257–265. doi: 10.2337/db13-1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Perkins BA, Rabbani N, Weston A, Ficociello LH, Adaikalakoteswari A, Niewczas M, Warram J, Krolewski AS, Thornalley P. Serum levels of advanced glycation endproducts and other markers of protein damage in early diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. PLoS One. 2012;7(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nigro C, Raciti G, Leone A, Fleming T, Longo M, Prevenzano I, Fiory F, Mirra P, D’Esposito V, Ulianich L, Nawroth P, Formisano P, Beguinot F, Miele C. Methylglyoxal impairs endothelial insulin sensitivity both in vitro and in vivo. Diabetologia. 2014;57(7):1485–1494. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim MJ, Kim DW, Lee BR, Shin MJ, Kim YN, Eom SA, Park BJ, Cho YS, Han KH, Park J, Hwang HS, Eum WS, Choi SY. Transduced tat-glyoxalase protein attenuates streptozotocin-induced diabetes in a mouse model. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013;430(1):294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.10.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Maessen DE, Hanssen NM, Scheijen JL, van der Kallen CJ, van Greevenbroek MM, Stehouwer CD, Schalkwijk CG. Post–glucose load plasma α-dicarbonyl concentrations are increased in individuals with impaired glucose metabolism and type 2 diabetes: the CODAM study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(5):913–920. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rabbani N, Sebekova K, Sebekova K, Jr., Heidland A, Thornalley PJ. Protein glycation, oxidation and nitration free adduct accumulation after bilateral nephrectomy and ureteral ligation. Kidney Int. 2007;72(9):1113–1121. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Agalou S, Ahmed N, Babaei-Jadidi R, Dawnay A, Thornalley PJ. Profound mishandling of protein glycation degradation products in uremia and dialysis. J. Amer. Soc. Nephrol. 2005;16(5):1471–1485. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004080635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nangaku M. Chronic hypoxia and Tubulointerstitial injury: a final common pathway to end-stage renal failure. J. Amer. Soc. Nephrol. 2006;17(1):17–25. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005070757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Reiniger N, Lau K, McCalla D, Eby B, Cheng B, Lu Y, Qu W, Quadri N, Ananthakrishnan R, Furmansky M, Rosario R, Song F, Rai V, Weinberg A, Friedman R, Ramasamy R, D'Agati V, Schmidt AM. Deletion of the receptor for advanced glycation end products reduces glomerulosclerosis and preserves renal function in the diabetic OVE26 mouse. Diabetes. 2010;59(8):2043–2054. doi: 10.2337/db09-1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Robin ED, Murphy BJ, Theodore J. Coordinate regulation of glycolysis by hypoxia in mammalian cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1984;118(3):287–290. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041180311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pietrzak I, Baczyk K. Erythrocyte transketolase activity and guandino compounds in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2001;59(S78):S97–S101. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.07837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Miyata T, van Ypersele de Strihou C, Imasawa T, Yoshino A, Ueda Y, Ogura H, Kominami K, Onogi H, Inagi R, Nangaku M, Kurokawa K. Glyoxalase I deficiency is associated with an unusual level of advanced glycation end products in a hemodialysis patient. Kidney Int. 2001;60(6):2351–2359. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rabbani N, Thornalley PJ. Glyoxalase in diabetes, obesity and related disorders. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011;22(3):309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mäkinen, V.-P., Civelek, M., Meng, Q., Zhang, B., Zhu, J., Levian, C., Huan, T., Segrè, A.V., Ghosh, S., Vivar, J., Nikpay, M., Stewart, A.F.R., Nelson, C.P., Willenborg, C., Erdmann, J., Blakenberg, S., O'Donnell, C.J., März, W., Laaksonen, R., Epstein, S.E., Kathiresan, S., Shah, S.H., Hazen, S.L., Reilly, M.P., Lusis, A.J., Samani, N.J., Schunkert, H., Quertermous, T., McPherson, R., Yang, X., Assimes, T.L., the Coronary, A.D.G.-W.R., Meta-Analysis, C.: Integrative Genomics Reveals Novel Molecular Pathways and Gene Networks for Coronary Artery Disease. PLoS Genet. 10(7), e1004502 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 108.Tikellis C, Pickering RJ, Tsorotes D, Huet O, Cooper ME, Jandeleit-Dahm K, Thomas MC. Dicarbonyl stress in the absence of hyperglycemia increases endothelial inflammation and atherogenesis similar to that observed in diabetes. Diabetes. 2014;63(11):3915–3925. doi: 10.2337/db13-0932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nin JW, Jorsal A, Ferreira I, Schalkwijk CG, Prins MH, Parving HH, Tarnow L, Rossing P, Stehouwer CD. Higher plasma levels of advanced glycation end products are associated with incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in type 1 diabetes a 12-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):442–447. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hanssen NMJ, Wouters K, Huijberts MS, Gijbels MJ, Sluimer JC, Scheijen JLJM, Heeneman S, Biessen EAL, Daemen MJAP, Brownlee M, de Kleijn DP, Stehouwer CDA, Pasterkamp G, Schalkwijk CG. Higher levels of advanced glycation endproducts in human carotid atherosclerotic plaques are associated with a rupture-prone phenotype. Eur. Heart J. 2014;35(17):1137–1146. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hanssen NMJ, Brouwers O, Gijbels MJ, Wouters K, Wijnands E, Cleutjens JPM, De Mey JG, Miyata T, Biessen EA, Stehouwer CDA, Schalkwijk CG. Glyoxalase 1 overexpression does not affect atherosclerotic lesion size and severity in ApoE−/− mice with or without diabetes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014;104(1):160–170. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Inagi R, Miyata T, Ueda Y, Yoshino A, Nangaku M, de Strihou CV, Kurokawa K. Efficient in vitro lowering of carbonyl stress by the glyoxalase system in conventional glucose peritoneal dialysis fluid. Kidney Int. 2002;62(2):679–687. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Godfrey L, Yamada-Fowler N, Smith JA, Thornalley PJ, Rabbani N. Arginine-directed glycation and decreased HDL plasma concentration and functionality. Nutrition and diabetes. 2014;4 doi: 10.1038/nutd.2014.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zender L, Xue W, Zuber J, Semighini CP, Krasnitz A, Ma B, Zender P, Kubicka S, Luk JM, Schirmacher P, Richard McCombie W, Wigler M, Hicks J, Hannon GJ, Powers S, Lowe SW. An Oncogenomics-based in vivo RNAi screen identifies tumor suppressors in liver cancer. Cell. 2008;135(5):852–864. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sakamoto H, Mashima T, Kazaki A, Dan S, Hashimoto Y, Naito M, Tsuruo T. Glyoxalase I is involved in resistance of human leukemia cells to antitumour agent-induced apoptosis. Blood. 2000;95(10):3214–3218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Santarius T, Bignell GR, Greenan CD, Widaa S, Chen L, Mahoney CL, Butler A, Edkins S, Waris S, Thornalley PJ, Futreal PA, Stratton MR. GLO1 - a novel amplified gene in human cancer. Genes Chromosom. Cancer. 2010;49(8):711–725. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Shibata T, Ohta T, Tong KI, Kokubu A, Odogawa R, Tsuta K, Asamura H, Yamamoto M, Hirohashi S. Cancer related mutations in NRF2 impair its recognition by Keap1-Cul3 E3 ligase and promote malignancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105(36):13568–13573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806268105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sakamoto H, Mashima T, Sato S, Hashimoto Y, Yamori T, Tsuruo T. Selective activation of apoptosis program by S-p-bromobenzylglutathione cyclopentyl diester in glyoxalase I-overexpressing human lung cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001;7(8):2513–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hovatta I, Tennant RS, Helton R, Marr RA, Singer O, Redwine JM, Ellison JA, Schadt EE, Verma IM, Lockhart DJ, Barlow C. Glyoxalase 1 and glutathione reductase 1 regulate anxiety in mice. Nature. 2005;438(7068):662–666. doi: 10.1038/nature04250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kromer SA, Kessler MS, Milfay D, Birg IN, Bunck M, Czibere L, Panhuysen M, Putz B, Deussing JM, Holsboer F, Landgraf R, Turck CW. Identification of glyoxalase-I as a protein marker in a mouse model of extremes in trait anxiety. J. Neurosci. 2005;25(17):4375–4384. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0115-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Distler MG, Plant LD, Sokoloff G, Hawk AJ, Aneas I, Wuenschell GE, Termini J, Meredith SC, Nobrega MA, Palmer AA. Glyoxalase 1 increases anxiety by reducing GABAA receptor agonist methylglyoxal. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122(6):2306–2315. doi: 10.1172/JCI61319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kurz A, Rabbani N, Walter M, Bonin M, Thornalley PJ, Auburger G, Gispert S. Alpha-synuclein deficiency leads to increased glyoxalase I expression and glycation stress. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011;68(4):721–733. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0483-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Conroy, P.J.: Carcinostatic activity of methylglyoxal and related substances in tumour-bearing mice. In: Submolecular Biology and Cancer: Ciba Foundation Symposium, vol. 67. pp. 271–298. Excerpta Medica, Amsterdam (1979) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 124.Arai M, Yuzawa H, Nohara I, Ohnishi T, Obata N, Iwayama Y, Haga S, Toyota T, Ujike H, Arai M, Ichikawa T, Nishida A, Tanaka Y, Furukawa A, Aikawa Y, Kuroda O, Niizato K, Izawa R, Nakamura K, Mori N, Matsuzawa D, Hashimoto K, Iyo M, Sora I, Matsushita M, Okazaki Y, Yoshikawa T, Miyata T, Itokawa M. Enhanced carbonyl stress in a subpopulation of schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):589–597. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ahmed N, Ahmed U, Thornalley PJ, Hager K, Fleischer GA, Munch G. Protein glycation, oxidation and nitration marker residues and free adducts of cerebrospinal fluid in Alzheimer's disease and link to cognitive impairment. J. Neurochem. 2004;92(2):255–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ferguson GP, Vanpatten S, Bucala R, Al Abed Y. Detoxification of methylglyoxal by the nucleophilic bidentate, phenylacylthiazolium bromide. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1999;12(7):617–622. doi: 10.1021/tx990007y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Thornalley PJ, Minhas HS. Rapid hydrolysis and slow alpha,beta-dicarbonyl cleavage of an agent proposed to cleave glucose-derived protein cross-links. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;57(3):303–307. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(98)00284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ruggiero-Lopez D, Lecomte M, Moinet G, Pattereau G, Legrarde M, Wiernsperger N. Reaction of metformin with dicarbonyl compounds. Possible implication in the inhibition of advanced glycation end product formation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;58(11):1765–1773. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kinsky OR, Hargraves TL, Anumol T, Jacobsen NE, Dai J, Snyder SA, Monks TJ, Lau SS. Metformin scavenges methylglyoxal to form a novel Imidazolinone metabolite in humans. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Battah S, Ahmed N, Thornalley PJ. Kinetics and mechanism of the reaction of metformin with methylglyoxal. Int. Congr. Ser. 2002;1245:355–356. doi: 10.1016/S0531-5131(02)00889-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Adrover M, Vilanova B, Frau J, Muñoz F, Donoso J. A comparative study of the chemical reactivity of pyridoxamine, Ac-Phe-Lys and Ac-Cys with various glycating carbonyl compounds. Amino Acids. 2009;36(3):437–448. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Alaei Shahmiri F, Soares MJ, Zhao Y, Sherriff J. High-dose thiamine supplementation improves glucose tolerance in hyperglycemic individuals: a randomized, double-blind cross-over trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2013;52(7):1821–1824. doi: 10.1007/s00394-013-0534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Rabbani N, Shahzad Alam S, Riaz S, Larkin JR, Akhtar MW, Shafi T, Thornalley PJ. High dose thiamine therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes and microalbuminuria: a pilot randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Diabetologia. 2009;52(2):208–212. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Xue, M., Momiji, H., Rabbani, N., Barker, G., Bretschneider, T., Shmygol, A., Rand, D.A., Thornalley, P.J.: Frequency modulated translocational oscillations of Nrf2 mediate the ARE cytoprotective transcriptional response Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 23(7), 613–629 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 135.Xue M, Momiji H, Rabbani N, Bretschneider T, Rand DA, Thornalley PJ. Frequency modulated translocational oscillations of Nrf2, a transcription factor functioning like a wireless sensor. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2015;43(4):669–673. doi: 10.1042/BST20150060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Malhotra D, Portales-Casamar E, Singh A, Srivastava S, Arenillas D, Happel C, Shyr C, Wakabayashi N, Kensler TW, Wasserman WW, Biswal S. Global mapping of binding sites for Nrf2 identifies novel targets in cell survival response through ChIP-Seq profiling and network analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(17):5718–5734. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Xue M., Weickert M.O., Qureshi S., Ngianga-Bakwin K., Anwar A., Waldron M., Shafie A., Messenger D., Fowler M., Jenkins G., Rabbani N., Thornalley P.J.: Improved glycemic control and vascular function in overweight and obese subjects by glyoxalase 1 inducer formulation diabetes. In: Press (2016). doi:10.2337/db2316-0153) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 138.Lo TWC, Thornalley PJ. Inhibition of proliferation of human leukemia 60 cells by diethyl esters of glyoxalase inhibitors in vitro. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1992;44(12):2357–2363. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90680-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Thornalley PJ. Advances in glyoxalase research. Glyoxalase expression in malignancy, anti-proliferative effects of methylglyoxal, glyoxalase I inhibitor diesters and S -D-lactoylglutathione, and methylglyoxal-modified protein binding and endocytosis by the advanced glycation endproduct receptor. Crit. Rev. in Oncol. and Haematol. 1995;20(1–2):99–128. doi: 10.1016/1040-8428(94)00149-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Sharkey EM, O'Neill HB, Kavarana MJ, Wang HB, Creighton DJ, Sentz DL, Eiseman JL. Pharmacokinetics and antitumor properties in tumor-bearing mice of an enediol analogue inhibitor of glyoxalase I. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2000;46(2):156–166. doi: 10.1007/s002800000130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]