Abstract

We describe the first case of gastritis in a male Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea) in which members of the family Helicobacteraceae, particularly the genus Wolinella, were detected. The sea lion exhibited clinical signs of gastrointestinal disease, including abdominal pain, lack of appetite, and lethargy. Examination of one ileal and five gastric biopsy specimens collected over a 10-year period revealed persistent fibrosis and/or superficial focal erosion and ulceration of the lamina propria. Spiral-shaped organisms 5 to 12 μm long were observed in two of the gut biopsy specimens. While Helicobacter species were detected by PCR in one of the gastric biopsy specimens, Wolinella species were detected in four of the five gastric specimens, including those in which spiral-shaped organisms were observed. Comparisons of biopsy specimen ribosomal DNA sequences with those obtained from the feces of this animal, the gastric tissue of a clinically healthy individual, and the feces of several other cohoused sea lions and fur seals revealed a separate and possibly novel gastric Helicobacter species. A possibly novel Wolinella species, along with Wolinella succinogenes, was also identified. These findings highlight the pathogenic potential of other members of this family in the etiopathogenesis of gastric disease in these animals.

Members of the family Helicobacteraceae, particularly the Helicobacter species, have been recognized as agents of gastrointestinal disease in both humans and a broad range of animal hosts (11, 26). While not all species are pathogenic (25), colonization of the gut by such organisms (particularly Helicobacter pylori) may lead to conditions of gastroenteritis, gastric ulceration, and gastric adenocarcinoma (1, 9). The genus Wolinella, like the genus Helicobacter, belongs to the epsilon subclass of the proteobacteria and is a member of the family Helicobacteraceae (29). However, as a natural inhabitant of the rumen of cattle (31), its role as a pathogen has not been described. In this article, we describe a case of chronic gastritis in a male Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea) and, through an examination of other, asymptomatic cohoused fur seals and sea lions, discuss the potential role of the family Helicobacteraceae in the etiopathogenesis of gastric disease in these animals.

CASE REPORT

In early March 1992, a 4-year-old male Australian sea lion (N. cinerea) that was named Duran and that had abdominal pain, lack of appetite, and lethargy was examined for a possible obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract. However, an exploratory laparotomy revealed no apparent obstruction. Instead, gas-filled loops of the small intestine that were purple in color and that had obvious poor perfusion were observed. A biopsy of the ileum revealed eosinophilic enteritis that was tentatively attributed to an enteric allergenic response. While the nature of the allergen was unclear, it was proposed that parasitic antigens and/or food allergens might cause similar reactions. However, despite the absence of any obvious etiological agent, the animal was subsequently treated for Helicobacter species infection over a 2-week period with amoxicillin (10 mg/kg of body weight twice daily) (SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, Dandenong, Victoria, Australia), prednisolone (30 mg daily) (Mavlab Pty Ltd., Slacks Creek, Queensland, Australia), and metronidazole (10 mg/kg twice daily) (Alphapharm Pty Ltd., Glebe, New South Wales, Australia).

While the animal exhibited some clinical signs of recovery after several days of treatment (bright, alert, and with an increased appetite), the animal appeared to relapse 2 weeks later. Further biopsy specimens obtained endoscopically from the stomach of the animal (in late March 1992) revealed the presence of active ulcerative gastritis in conjunction with some poorly preserved spiral-shaped structures suggestive of Helicobacter. The animal was subsequently continued on the previous antibiotic treatment regimen.

A substantial improvement in the animal's condition was reported several weeks later (mid-April 1992) and was substantiated by resolving gastritis noted in a second endoscopic examination of the stomach. Nevertheless, the animal continued to exhibit intermittent signs of abdominal discomfort in association with a loss of appetite and a strange hiccough-like behavior between May 1992 and March 2002. Broad-spectrum antibiotics (amoxicillin at 10 mg/kg twice daily [SmithKline Beecham] and omeprazole at 20 mg daily [Astrazeneca Pty Ltd., North Ryde, New South Wales, Australia]) were periodically continued, and further biopsy specimens were taken from the stomach in May 1992, May 2000, and March 2002 for histopathological evaluation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Histopathological analysis.

One ileal and five gastric biopsy specimens were obtained from a male Australian sea lion (N. cinerea) named Duran between 1992 and 2002 (A1 to A6). Also, as a control, a gastric biopsy specimen was obtained from a clinically healthy and cohoused female Australian sea lion named Portia in 1992. Tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at a thickness of 2 to 4 μm. Samples were subsequently stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and examined microscopically for signs of infection (inflammation and/or ulceration) like those associated with Helicobacter infections in other animals.

Collection of fecal samples.

Fecal samples were collected in 2003 from the nightly enclosures of Duran, Portia, and four other cohoused fur seals and sea lions (Bella, Groucher, Massey, and Shilo) from UnderWater World (Mooloolaba, Queensland, Australia). A 20-g sample was collected from each individual, placed in a sterile collection vial containing 40 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 20% glycerol, mixed, and placed immediately on ice.

Total DNA extraction.

For each biopsy specimen, approximately 15 mg of paraffin-embedded tissue was removed with a sterile scalpel blade and added to a sterile 2-ml microcentrifuge tube. Total DNA was extracted from the sections by using a QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen, Clifton Hill, Victoria, Australia) and reeluted in 100 μl of elution buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.5).

Fecal samples were homogenized for 2 min, and a 200-μl aliquot (or approximately 200 mg) was removed and placed in a sterile 2-ml microcentrifuge tube. Total DNA was extracted from the feces by using a QIAamp DNA stool minikit (Qiagen) and reeluted in 200 μl of elution buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.5).

PCR conditions.

To establish whether Helicobacter species were present in biopsy specimens or fecal samples, the following genus-specific primers were used to produce 16S rRNA amplicons approximately 400 bp long: 5′-TATGACGGGTATCCGGC-3′ (H276 forward) and 5′-ATTCCACCTACCTCTCCCA-3′ (H676 reverse) (12). Total volumes of 30 μl were used in all PCRs, which were performed by using a Mastercycler gradient (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Reaction mixtures contained 25 pmol of each primer, 1× PCR buffer [67 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 16.6 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.45% Triton X-100, 0.2 mg of gelatin/ml], 2.5 mM MgCl2, 170 μM deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate, 1.0 U of Taq polymerase (Biotech International, Perth, Western Australia, Australia), and 2 μl of DNA extract. All reactions were heated at 94°C for 2 min and then subjected to 30 cycles consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 66°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. For biopsy specimens, a 2-μl aliquot from each of the initial PCRs (including the controls [see below]) was added to the above reaction mixture and subjected to a second round of amplification (total of 60 cycles). A 5-μl aliquot from each of the PCRs was separated by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV light. The image was recorded by using GeneSnap (version 4.00.00) (Syngene [a division of Synoptics Ltd.], Cambridge, England).

PCR controls.

To verify the results of the PCRs, several controls were included with each series of reactions. These included one positive and two negative controls. The positive control was used to verify the success of the PCR and contained 2 μl of H. pylori strain 26695 genomic DNA (School of Microbiology and Immunology, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia). The negative controls were used to detect the presence of false amplification products and contained either 2 μl of Escherichia coli genomic DNA or 2 μl of water.

Cloning, plasmid isolation, and sequencing.

Amplicons were cloned by using a pGEM-T Easy Vector system (Promega). In accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, 3 μl of PCR product was ligated with 50 ng of vector at room temperature for 1 h and transformed with high-efficiency JM109 competent cells (Promega). Clones were selected by using ampicillin plates containing isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) and screened for inserts by using a CloneChecker system (Invitrogen, Mulgrave, Queensland, Australia). Plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli JM109 cells by using a Wizard Plus SV Minipreps DNA purification system (Promega). DNA was submitted to the Australian Genome Research Facility and sequenced with an ABI Prism BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

Sequence analysis.

Sequences obtained from both biopsy and fecal samples were entered into the BioEdit sequence alignment editor for Windows 95/98/NT (version 5.0.9) (15) and aligned by using CLUSTAL W (version 1.4) (28). Sequences retrieved from the GenBank database for H. pylori, Arcobacter nitrofigilis, Sulfurospirillum deleyianum, and several Campylobacter and Wolinella species were included with this alignment as reference sequences. Also, sequences from both biopsy and fecal samples were aligned with sequences of other Helicobacter and Campylobacter species retrieved from GenBank to determine the variation (if any) between these sequences and those of other species. A difference in nucleotide sequence of approximately 3% or greater between any two ribosomal DNAs was used to distinguish a separate species (5, 10, 18, 27). Tree diagrams representing these alignments were constructed with the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis program (version 2.1) (19) by using the neighbor-joining method.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences determined in this study were deposited under the following GenBank accession numbers: for Duran's biopsy specimens—B210210 (A2), AY501370; B211689 (A3), AY501371; B214747 (A4), AY501372; B019694 (A5), AY501373; and B212633 (A6), AY501374; for Portia's biopsy specimen—B211685, AY606046; and for the feces of the captive seals—Duran (DN210503), AY501375; Portia (PT210503), AY501378; Bella (BE210503), AY501376; Shilo (SH210503), AY501377; Groucher (GH210503), AY501399; and Massey (MY210503), AY501340.

RESULTS

Histopathological findings.

One ileal and five gastric biopsy specimens taken from Duran over a 10-year period as well as a control specimen taken from a clinically healthy female sea lion (Portia) were examined for pathological features consistent with infections caused by members of the genus Helicobacter. Photomicrographs of the control specimen and several gastric biopsy specimens exhibiting distinct pathological features and/or the presence of a possible etiological agent from Duran are shown in Fig. 1 to 3.

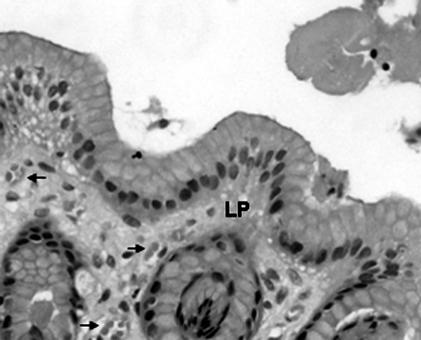

FIG. 1.

Histological section B211685 (control) from the stomach of Portia, a clinically healthy female Australian sea lion (N. cinerea). Several small focal but loose accumulations of lymphocytes and plasma cells (arrows) are observed within the lamina propria (LP). No fibrosis, ulceration, or spiral-shaped bodies are evident. Hematoxylin and eosin stain; magnification: ×340.

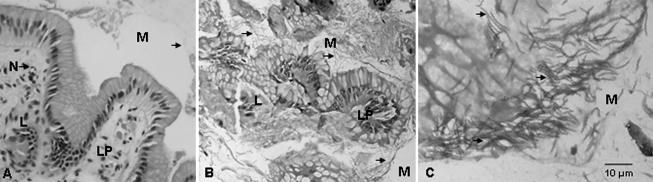

FIG. 3.

Histological section B019694 (A5) from the stomach of Duran, a male Australian sea lion with gastritis. (A to C) The lamina propria (LP) is expanded and features congestion and infiltrates of lymphoid cells (L) and neutrophils (N). Immense numbers of spiral-shaped bodies (arrows) are observed in the superficial mucus layer (M). HE stain; magnifications: A and B, ×400; C, ×1,000.

Small focal but inconsequential loose accumulations of lymphocytes and plasma cells were detected in the lamina propria of the control gastric tissue specimen collected from Portia (Fig. 1). As these changes occurred in the absence of fibrosis, ulceration, and spiral-shaped bodies, they may be considered to be within normal limits and thus may be representative of the normal gastric mucosa.

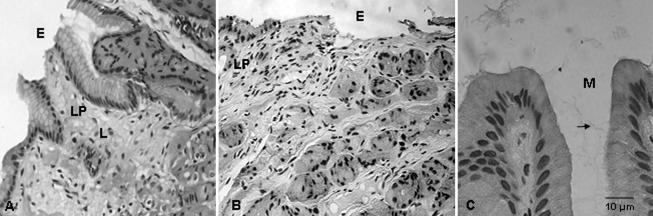

Mild to moderate enteritis characterized by a hypercellular lamina propria consisting of infiltrates of eosinophils, mast cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells was observed for the ileal biopsy specimen (A1) obtained in March 1992 (data not shown). While these features may be indicative of an enteric allergenic response, no etiological agent was observed. For the gastric biopsy specimen (A2) collected in April 1992, however, some spiral-shaped bodies approximately 10 μm in length (although poorly preserved) were observed in the superficial mucus layer (Fig. 2). In comparison with the findings for the control (Fig. 1), these spiral-shaped bodies occurred in association with moderate to severe gastritis, which was characterized by superficial focal erosion, ulceration, and fibrosis of the lamina propria with infiltrates of lymphocytes; these features most likely represented the etiological agent. However, no spiral-shaped bodies were observed in a second gastric biopsy specimen (A3) taken approximately 14 days later (data not shown). With a focal loss of glands and replacement fibrosis associated with a mild infiltration of monocytes in the lamina propria, this specimen was in marked contrast to specimen A2 and thus may have indicated resolving gastritis. Nevertheless, mild gastritis featuring fibrosing lymphocytic infiltration of the lamina propria and congestion of the superficial mucosa was observed for the gastric biopsy specimen (A4) obtained 4 weeks later, in May 1992 (data not shown). However, no spiral-shaped bodies were observed in this specimen.

FIG. 2.

Histological section B210210 (A2) from the stomach of Duran, a male Australian sea lion with gastritis. (A and B) The gastritis is characterized by fibrosing lymphocytic-plasmacytic (L) infiltration of the lamina propria (LP), with focal superficial erosion and ulceration (E). (C) Small numbers of poorly preserved spiral-shaped bodies (arrow) are observed in the superficial mucus layer (M). HE stain; magnifications: A and B, ×400; C, ×1,000.

For the gastric biopsy specimen (A5) collected 10 years later, in May 2000, an expanded lamina propria featuring congestion, focal hemorrhage, and infiltration of lymphoid cells and neutrophils was observed (Fig. 3). In contrast to the findings for the control specimen and Duran's previous biopsy specimens, immense numbers of spiral-shaped organisms approximately 5 to 12 μm in length were observed in the superficial mucus layer.

However, no spiral-shaped organisms were observed in the gastric biopsy specimen (A6) taken in March 2002. Despite this finding, mild gastritis characterized by fibrosis of the superficial submucosa with infiltrates of mononuclear cells was apparent (data not shown).

PCR detection of species of the family Helicobacteraceae.

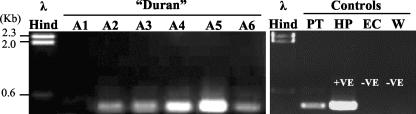

PCR analysis of paraffin-embedded gut biopsy specimens collected from Duran over a 10-year period is shown in Fig. 4. Amplicons of the expected size of approximately 400 bp were observed for all gastric biopsy specimens collected between 1992 and 2002 (A2 to A6). However, no amplification product was observed for the ileal biopsy specimen collected in March 1992 (A1). Interestingly, while a product was observed for biopsy specimen A5, which featured immense numbers of spiral-shaped organisms, products also were observed for biopsy specimens in which no such organisms were seen (A3, A4, and A6).

FIG. 4.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products produced from total DNA extracted from paraffin-embedded gut biopsy specimens from Duran, a male Australian sea lion. A1 to A6 correspond to the code numbers used in the histological images. Experimental controls include the following: PT, total DNA extract from a paraffin-embedded control biopsy specimen (B211685) taken from a clinically healthy sea lion named Portia; HP, H. pylori genomic DNA; EC, E. coli genomic DNA; W, water (no template); λ Hind, molecular weight marker (λ phage DNA cut with HindIII).

Amplicons of the expected size of approximately 400 bp were also observed for the control biopsy specimen taken from Portia in 1992 (Fig. 4) and the fecal samples collected from Duran, Portia, and the other cohoused seals in 2003 (data not shown).

Sequence analysis.

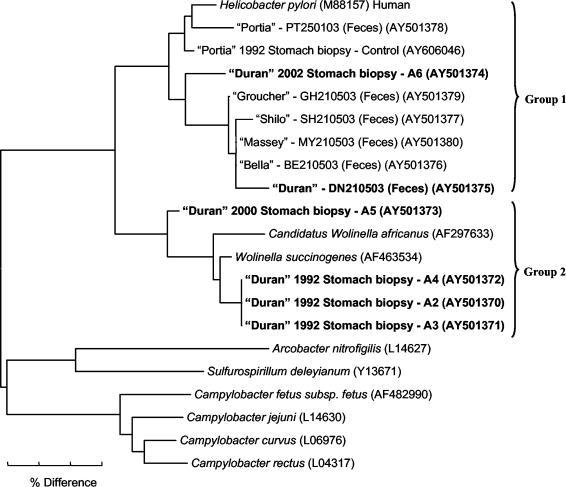

A tree demonstrating the alignment of 16S rRNA sequences from amplicons recovered from gastric biopsy specimens collected from Duran over a 10-year period (1992 to 2002), the gastric biopsy specimen collected from Portia in 1992, and fecal samples obtained from Duran, Portia, and several other cohoused seals in 2003 is shown in Fig. 5. Two main groups of sequences differing by more than 20 bp (95% identity) were observed. Group 1 consisted of sequences that clustered with the Helicobacter type species H. pylori and included both a fecal sequence and a gastric biopsy sequence (A6) obtained from Duran in 2003 and 2002, respectively. Sequences obtained from the gut biopsy and fecal specimens from Portia as well as fecal specimens from the other cohoused seals (Shilo, Massey, Groucher, and Bella) also clustered within this group. While a difference of no more than 6 bp (98.4% identity) was observed between sequences obtained from fecal specimens from Duran and the other seals (with the exception of Portia), a difference of 11 to 16 bp (96 to 97.3% identity) was observed between these sequences and the sequence obtained from gastric biopsy specimen A6 from Duran. The sequence obtained from gastric biopsy specimen A6 from Duran thus may represent a Helicobacter species distinct from that obtained from his feces or the feces from the other seals.

FIG. 5.

Neighbor-joining tree demonstrating the 16S rRNA sequence identity among species of the family Helicobacteraceae in gut biopsy specimens collected from a male Australian sea lion (Duran) over several years, a gut biopsy specimen collected from a clinically healthy sea lion (Portia), and fecal material collected from Duran, Portia, and several other cohoused seals. Code numbers for biopsy samples are included and correspond to those used in the histological images. H. pylori, Wolinella spp., and Campylobacter spp. are included as reference sequences. The scale bar represents a 3% difference in nucleotide sequences. GenBank accession numbers are given in parentheses. Specimens with sequences of interest are shown in boldface characters.

While the sequence obtained from Portia's gastric biopsy specimen differed from that obtained from her feces by no more than 7 bp (98% identity), a difference of 10 to 16 bp (96 to 97.4% identity) was observed among this sequence, the sequence obtained from gut biopsy specimen A6 from Duran, and the sequences obtained from the feces from all of the other seals. The sequence obtained from Portia's gastric tissue thus may represent a Helicobacter species distinct from that obtained from gut biopsy specimen A6 from Duran or the feces from the other seals.

Interestingly, group 2 consisted of sequences from the Wolinella type species Wolinella succinogenes, a sequence from a putative Wolinella species (“Candidatus Wolinella africanus”), and sequences obtained from four gastric biopsy specimens collected from Duran in 1992 and 2000 (A2, A3, A4, and A5). While this finding may demonstrate the apparent lack of Helicobacter specificity in the current PCR assay, it is surprising that given the large numbers of spiral-shaped organisms observed in biopsy specimen A5, a sequence similar to that of the genus Wolinella was recovered. No difference in nucleotide sequence (100% identity) was observed among sequences obtained from biopsy specimens A2, A3, and A4; these sequences thus may represent the same species. Moreover, no more than a 5-bp difference (98.7% identity) was observed between these sequences and the W. succinogenes sequence; these sequences thus may represent this organism. The sequence obtained from gastric biopsy specimen A5, however, differed from these gastric biopsy specimen sequences and the Wolinella sp. sequence by 11 to 14 bp (96.5 to 97.2% identity); this sequence thus may represent a separate and possibly novel Wolinella species.

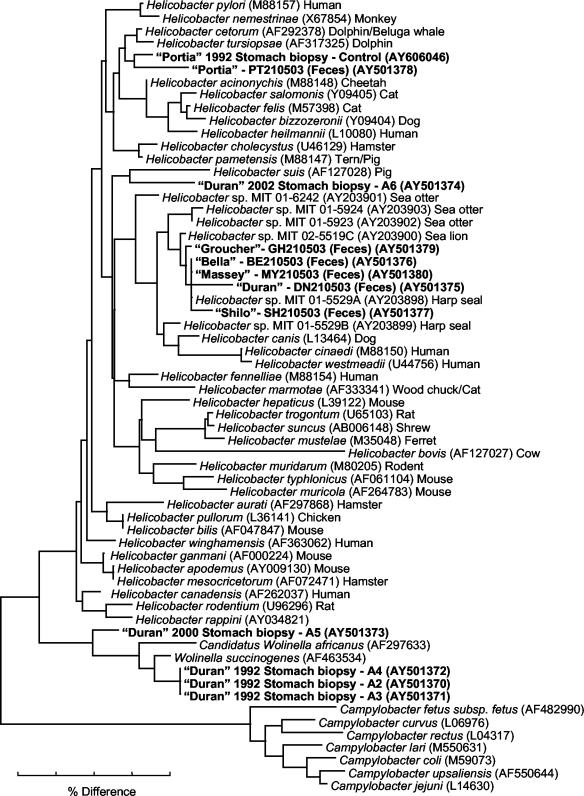

A tree diagram representing the alignment of 16S rRNA sequences obtained from the fecal and gastric biopsy specimens collected from Duran and Portia, the fecal specimens collected from the other cohoused seals, and other bacterial species contained in the GenBank database is shown in Fig. 6. Despite a comparison with 40 other Helicobacter species, sequences obtained from four of the five gastric biopsy specimens collected from Duran (A2, A3, A4, and A5) remained as a cluster with members of the genus Wolinella. Only the sequence obtained from one biopsy specimen (A6) clustered with members of the genus Helicobacter. In particular, this sequence, although clustering with a Helicobacter species previously identified from pigs (namely, Helicobacter suis), differed from this sequence and all other sequences by at least 12 bp (97% identity) and thus may represent a novel species.

FIG. 6.

Neighbor-joining tree demonstrating the 16S rRNA sequence identity among organisms contained within the GenBank database and sequences of the family Helicobacteraceae in gut biopsy specimens collected from a male Australian sea lion (Duran) over several years, a biopsy specimen collected from a clinically healthy sea lion (Portia), and fecal material collected from Duran, Portia, and several other cohoused seals in 2003. Code numbers for biopsy samples are included and correspond to those used in the histological images. The scale bar represents a 4% difference in nucleotide sequences. GenBank accession numbers are given in parentheses. Specimens with sequences of interest are shown in boldface characters.

Interestingly, while the sequence obtained from Duran's fecal specimens differed from those obtained from his biopsy specimens, this sequence (with a difference of 4 to 11 bp [97.2 to 98.9% identity]) clustered with Helicobacter species previously identified from other marine mammals, including harp seals (Helicobacter sp. strain MIT 01-5529A), sea lions (Helicobacter sp. strain MIT 02-5519C), and sea otters (Helicobacter sp. strain MIT 01-5924). In addition, with the exception of Portia (whose sequences clustered with Helicobacter species from dolphins and whales), sequences obtained from the feces of all of the other seals, differing by no more than 0 to 8 bp (97.9 to 100% identity), also clustered with this group of sequences.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we report on the occurrence of species of the family Helicobacteraceae within the gut of a male Australian sea lion with gastritis. Despite continued treatment, this condition was (in comparison to the control) characterized by persistent inflammation and/or ulceration of the superficial gastric mucosa over a 10-year period (March 1992 to March 2002). While no etiological agent was observed for the majority of biopsy specimens, spiral-shaped organisms approximately 5 to 12 μm in length were apparent in two gastric biopsy specimens exhibiting marked erosion, ulceration, and fibrosis of the lamina propria (A2 and A5). Interestingly, given that such organisms appear to be morphologically consistent with members of the genus Helicobacter that cause similar conditions of disease in humans and a broad range of animal hosts (10, 26), such organisms may represent the etiological agent in this animal. However, considering that infections by such organisms may often be persistent despite treatment (23), the inability of the current antibiotic treatment regimen (10 mg of amoxicillin/kg twice daily) to effectively treat this animal requires review.

Sequences similar to those of the genus Wolinella rather than to those of the genus Helicobacter were, however, obtained from PCR products from four of the six biopsy specimens collected from Duran, including specimens in which spiral-shaped organisms were observed (A2 and A5). Interestingly, for three of these specimens (A2, A3, and A4), a sequence similar to the sequence of the type species W. succinogenes was recovered. This species, despite the absence of evidence to support it being pathogenic in humans or animals, supports numerous virulence genes homologous to those in other closely related and well-recognized pathogenic species (namely, H. pylori and Campylobacter jejuni) (2). Given that this species maintains curved or helical rod-shaped features (20) similar to those observed for many Helicobacter species (26), it is possible that this species represents the spiral-shaped organisms observed in these specimens. Nevertheless, its occurrence in this host is unique and reflects an ecological niche outside the bovine rumen (2). Moreover, its detection in association with gastritis has not been previously reported and merits further examination.

Of particular interest in this study was the detection of a putative novel Wolinella species in one of Duran's gastric biopsy specimens (A5), in which gastritis and immense numbers of spiral-shaped organisms were observed. While such organisms (as previously stated) are morphologically consistent with the genus Helicobacter (26), it is surprising that given the large numbers of these organisms, a sequence similar to that of Wolinella was recovered. Despite the fact that only one species (W. succinogenes) has been described to date, another putative novel species (namely, “Candidatus W. africanus”) was recently detected by PCR in patients with esophageal carcinoma (3). Given the substantial difference in nucleotide sequence (approximately 7 to 12%) from more than 40 Helicobacter and Campylobacter sequences, it is likely that this sequence represents a novel species. However, as the 16S rRNA sequence is not sufficient to describe a new species (7), other studies clearly are required to isolate and characterize this organism. Nevertheless, given the morphological variation between Helicobacter species (26), this putative novel Wolinella species may be representative of the spiral-shaped organisms observed in this biopsy specimen and may reflect the potential for more than one Wolinella species to infect this host.

A Helicobacter sequence type different from those previously detected in the gastric mucosa of wild harp seals exhibiting similar histopathological features of gastritis (17) was also recovered from a gastric biopsy specimen (A6) from Duran. While no spiral-shaped organisms were observed in this (or the control) specimen, such Helicobacter-like organisms may not always be detected by standard staining procedures such as HE staining (4). Despite this limitation, its detection in the gut of this host, given the ability of other species to cause similar conditions of disease in other marine mammals (16, 17), is novel and reflects the potential for multiple genera of the family Helicobacteraceae to infect this host. Coinfection of a host by closely related taxa has some precedence in the literature and has been reported for Campylobacter, Helicobacter, and Wolinella species (3, 24). While any of these species may have been responsible for the development of gastritis in this animal, they also may have been mere bystanders (3), as species of Helicobacter, like those of Wolinella, may be nonpathogenic in their natural host (25, 26). Indeed, with the detection of Helicobacter species in the gut of a clinically healthy sea lion (Portia) exhibiting no significant pathological features consistent with Helicobacter infections in other animals (16, 17), the role of Helicobacter in this host requires further examination.

Interestingly, the Helicobacter sequence obtained from one of Duran's gastric biopsy specimens was different from that recovered from his feces or feces from the other seals. Moreover, while this sequence was different from that obtained from gastric tissue and feces from the clinically healthy sea lion (Portia), the sequence obtained from feces from Duran and the other seals clustered together with sequences from Helicobacter species from other marine mammals. Since gastric Helicobacter species are not often detected in the feces of the host (14, 30), such sequences (despite recovery from Duran's ileal biopsy specimen) may have been representative of an enteric species common to both Duran and the other seals. However, since multiple gastric and enteric species may commonly colonize the digestive systems of a wide variety of hosts (11, 26), the recovery of different Helicobacter sequence types from gut biopsy specimens from Portia and Duran may represent the potential for more than one species to colonize the gut of these animals.

Although it is unclear (without further endoscopic examination) whether other seals in this population shared similar gastric Helicobacter (or even Wolinella) species, it is interesting that only Duran exhibited clinical signs of disease. However, as the relationship between disease and infection is often host specific (6, 13, 21), it is not surprising that animals like Duran may suffer from such infections while other animals like Portia remain asymptomatic. Nevertheless, since clinical disease may be absent in the presence of profound pathological changes (8, 22, 26) or, more importantly, that organisms like Helicobacter may establish persistent infections despite activating host defense responses (23), further studies should be directed to the routine endoscopic examination of asymptomatic animals. The extent of these infections may be better elucidated by such studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank UnderWater World and its staff for their support and cooperation in the collection of samples, in particular, Greg Elks, Kristy Rychdalvalsky, Chris Groot, Lucas Robinson, Brad McKenzie, and Malcolm Westwood. We also thank IDEXX Laboratories (Brisbane, Queensland, Australia) and its staff for their kind assistance in the preparation of histological specimens, in particular, Richard Miller, Emma Baggs, and John Moushall.

This work was supported by the School of Biological, Cellular, and Molecular Sciences, University of New England, and the National Marine Science Centre, Coffs Harbour, New South Wales, Australia. Support was also provided by the Faculty of Science, University of the Sunshine Coast.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asghar, R. J., and J. Parsonnet. 2001. Helicobacter pylori and risk for gastric adenocarcinoma. Semin. Gastrointest. Dis. 12:203-208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baar, C., M. Eppinger, G. Raddatz, J. Simon, C. Lanz, O. Klimmek, R. Nandakumar, R. Gross, A. Rosinus, H. Keller, P. Jagtap, B. Linke, F. Meyer, H. Lederer, and S. C. Schuster. 2003. Complete genome sequence and analysis of Wolinella succinogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:11690-11695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohr, U. R., I. Segal, A. Primus, T. Wex, H. Hassan, R. Ally, and P. Malfertheiner. 2003. Detection of a putative novel Wolinella species in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Helicobacter 8:608-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casazza, S., G. Tunesi, E. Marinaro, F. Caruso, M. Canepa, P. Michetti, and S. Rovida. 1997. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in 201 stomach biopsies using the polymerase chain reaction, histological staining (H&E/Giemsa) and immunohistochemistry. Pathologica 89:405-411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clayton, R. A., G. Sutton, P. S. Hinkle, Jr., C. Bult, and C. Fields. 1995. Intraspecific variation in small-subunit rRNA sequences in GenBank: why single sequences may not adequately represent prokaryotic taxa. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:595-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cover, T. L. 1997. Commentary: Helicobacter pylori transmission, host factors, and bacterial factors. Gastroenterology 113:S29-S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dewhirst, F. E., J. G. Fox, and S. L. On. 2000. Recommended minimal standards for describing new species of the genus Helicobacter. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:2231-2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dooley, C. P., H. Cohen, P. L. Fitzgibbons, M. Bauer, M. D. Appleman, G. I. Perez-Perez, and M. J. Blaser. 1989. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and histologic gastritis in asymptomatic persons. N. Engl. J. Med. 321:1562-1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernst, P. B., and B. D. Gold. 2000. The disease spectrum of Helicobacter pylori: the immunopathogenesis of gastroduodenal ulcer and gastric cancer. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:615-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox, G. E., J. D. Wisotzkey, and P. Jurtshuk, Jr. 1992. How close is close: 16S rRNA sequence identity may not be sufficient to guarantee species identity. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42:166-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox, J. G., and A. Lee. 1997. The role of Helicobacter species in newly recognized gastrointestinal tract diseases of animals. Lab. Anim. Sci. 47:222-255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Germani, Y., C. Dauga, P. Duval, M. Huerre, M. Levy, G. Pialoux, P. Sansonetti, and P. A. Grimont. Strategy for the detection of Helicobacter species by amplification of 16S rRNA genes and identification of H. felis in a human gastric biopsy. Res. Microbiol. 148:315-326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Go, M. F. 1997. What are the host factors that place an individual at risk for Helicobacter pylori-associated disease? Gastroenterology 113:S15-S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gramley, W. A., A. Asghar, H. F. Frierson, Jr., and S. M. Powell. 1999. Detection of Helicobacter pylori DNA in fecal samples from infected individuals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2236-2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall, T. A. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41:95-98. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harper, C. G., Y. Feng, S. Xu, N. S. Taylor, M. Kinsel, F. E. Dewhirst, B. J. Paster, M. Greenwell, G. Levine, A. Rogers, and J. G. Fox. 2002. Helicobacter cetorum sp. nov., a urease-positive Helicobacter species isolated from dolphins and whales. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4536-4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harper, C. G., S. Xu, A. B. Rogers, Y. Feng, Z. Shen, N. S. Taylor, F. E. Dewhirst, B. J. Paster, M. Miller, J. Hurley, and J. G. Fox. 2003. Isolation and characterization of novel Helicobacter spp. from the gastric mucosa of harp seals, Phoca groenlandica. Dis. Aquat. Org. 57:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolbert, C. P., and D. H. Persing. 1999. Ribosomal DNA sequencing as a tool for identification of bacterial pathogens. Curr. Microbiol. 2:299-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, I. B. Jakobsen, and M. Nei. 2001. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics 17:1244-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kupper, J., I. Wildhaber, Z. Gao, and E. Baeuerlein. 1989. Basal-body-associated disks are additional structural elements of the flagellar apparatus isolated from Wolinella succinogenes. J. Bacteriol. 171:2803-2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, H., C. Stoicov, X. Cai, T. C. Wang, and J. Houghton. 2003. Helicobacter and gastric cancer disease mechanisms: host response and disease susceptibility. J. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 5:459-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazzucchelli, L., C. H. Wilder-Smith, C. Ruchti, B. Meyer-Wyss, and H. S. Merki. 1994. Gastrospirillum hominis in asymptomatic, healthy individuals. Dig. Dis. Sci. 38:2087-2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhen, M., S. Eriksson, M. Clements, S. Bergstrom, and S. J. Normark. 2003. The basis of persistent bacterial infections. Trends Microbiol. 11:80-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen, Z., Y. Feng, F. E. Dewhirst, and J. G. Fox. 2001. Coinfection of enteric Helicobacter spp. and Campylobacter spp. in cats. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2166-2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simmons, J. H., L. K. Riley, C. L. Besch-Williford, and C. L. Franklin. 2000. Helicobacter mesocricetorum sp. nov., a novel Helicobacter isolated from the feces of Syrian hamsters. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1811-1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solnick, J. V., and D. B. Schauer. 2001. Emergence of diverse Helicobacter species in the pathogenesis of gastric and enterohepatic diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:59-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stackebrandt, E., and B. M. Goebel. 1994. Taxonomic note: a place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44:846-849. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Vandamme, P., E. Falsen, R. Rossau, B. Hoste, P. Segers, R. Tytgat, and J. De Ley. 1991. Revision of Campylobacter, Helicobacter, and Wolinella taxonomy: emendation of generic descriptions and proposal of Arcobacter gen. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41:88-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Zwet, A. A., J. C. Thijs, A. M. Kooistra-Smid, J. Schirm, and J. A. Snijder. 1994. Use of PCR with feces for detection of Helicobacter pylori infections in patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1346-1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolin, M. J., E. A. Wolin, and N. J. Jacobs. 1961. Cytochrome-producing anaerobic vibrio, Vibrio succinogenes sp. nov. J. Bacteriol. 81:911-917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]