Abstract

Background

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) causes significant cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Current consensus guidelines reflect the neutral results from randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Adequate trial reporting is a fundamental requirement before concluding on RCT intervention efficacy and is necessary for accurate meta-analysis and to provide insight into future trial design. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 statement provides a framework for complete trial reporting. Reporting quality of HFpEF RCTs has not been previously assessed, and this represents an important validation of reporting qualities to date.

Objectives

The aim was to systematically identify RCTs investigating the efficacy of pharmacological therapies in HFpEF and to assess the quality of reporting using the CONSORT 2010 statement.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL databases were searched from January 1996 to November 2015, with RCTs assessing pharmacological therapies on clinical outcomes in HFpEF patients included. The quality of reporting was assessed against the CONSORT 2010 checklist.

Results

A total of 33 RCTs were included. The mean CONSORT score was 55.4% (SD 17.2%). The CONSORT score was strongly correlated with journal impact factor (r=0.53, p=0.003) and publication year (r=0.50, p=0.003). Articles published after the introduction of CONSORT 2010 statement had a significantly higher mean score compared with those published before (64% vs 50%, p=0.02).

Conclusions

Although the CONSORT score has increased with time, a significant proportion of HFpEF RCTs showed inadequate reporting standards. The level of adherence to CONSORT criteria could have an impact on the validity of trials and hence the interpretation of intervention efficacy. We recommend improving compliance with the CONSORT statement for future RCTs.

Keywords: HEART FAILURE

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Several studies have shown that a significant proportion of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrate poor reporting standards despite the availability of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is a considerable source of morbidity and mortality, with no known disease-modifying treatments. The role of reporting of HFpEF trial findings has not been assessed, and the size of the problem is not known.

What does this study add?

We present the first systematic assessment of reporting standards for RCTs investigating therapies for HFpEF using CONSORT, and identify trends and areas which authors, reviewers and journal editorial boards can target for improvement.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Improvements in trial reporting and provision of relevant information for HFpEF will allow important post hoc analysis of trial findings and guide future trial design. This will provide a greater understanding of HFpEF heterogeneity and help to identify phenotypes with tailored therapies.

Introduction

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) along with meta-analysis provide the highest level of evidence on the efficacy of healthcare interventions. Accurate interpretation of results and critical appraisal of RCTs depends on adequate reporting and a study design that is free from bias. Studies have shown poor reporting standards in RCTs,1 particularly so in areas concerning trial methodology.2 3 The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement,4 updated in 2010, aims to improve the quality of reporting clinical trials, allowing results to be better interpreted and critically appraised.

Heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (HFpEF) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality, comparable to heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (HFrEF). HFpEF is the cause of symptomatic heart failure in over half of cases, with increasing prevalence in an increasingly ageing population.5 The recently published European Society of Cardiology heart failure guidelines reflect the absence of disease-modifying effects demonstrated in HFpEF RCTs and meta-analyses.6–10

The absence of evidence for HFpEF treatment efficacy may be due to differing pathophysiological processes compared with that for HFrEF, difficulty in clinical diagnosis and heterogeneity of included study populations with subgroup phenotypes. In addition to these well-recognised issues, clear reporting of HFpEF trials is a fundamental requirement to assess the appraisal of methodological approaches and validity of results, as well as for the accuracy of meta-analysis and subgroup analysis. Adequate reporting of information specifically relevant to issues in the HFpEF trial design will also help direct future clinical trial design to optimise effectiveness. Trends in the quality of HFpEF trial reporting and areas for improvement that will be of clinical and research benefit have not previously been reported.

The aim of this study was to systematically identify RCTs investigating the efficacy of pharmacological therapies in HFpEF published between 1996 and 2015, to assess quality of reporting using the CONSORT 2010 statement and also to identify temporal trends.

Methods

This article has been reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.11

Search strategy

We systematically searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL databases for all clinical trials using the keywords: heart failure and normal ejection fraction, heart failure and preserved cardiac function, heart failure and preserved ejection fraction, diastolic heart failure, diastolic dysfunction, HFpEF and HFnEF (see online supplementary material table S1 for full search protocol). Results were filtered for RCTs using predesigned and validated filters. The search was run on 20 November 2015, with results included from 1 January 1996 to 20 November 2015. The reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews were searched for additional studies. No published study protocol exists for this systematic review.

openhrt-2016-000449supp.pdf (453.1KB, pdf)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (1) RCT, (2) trial inclusion criteria specifying heart failure signs and symptoms with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥40%, (3) pharmacological intervention with placebo or pharmacological comparison and (4) outcomes including all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, hospitalisation and changes in New York Heart Association functional class (NYHA), exercise capacity (6-min walking distance, VO2 max) or quality of life (measured using the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire).

Exclusion criteria were: (1) treatment of acute heart failure, (2) treatment duration <7 days, (3) studies using healthy controls, (4) non-English language publications, (5) abstracts and conference publications and (6) unpublished studies.

Study selection

After the removal of duplicates, the title and abstracts of initial search results were screened for relevance. The full texts of remaining results were independently assessed by three authors (SLZ, FTC, EM) for inclusion based on predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The final list of included studies was decided by discussion between authors and required full agreement. Remaining disagreements were resolved by AAN.

Assessment of quality

Reporting quality was assessed using the CONSORT 2010 score (table 1). Each item on the checklist was answered ‘Yes’, ‘No’ or ‘Not Applicable (NA)’, with each ‘Yes’ scoring 1 point. Each item was weighted equally. An overall reporting quality score percentage was calculated for each study by dividing the number of points by the total available (excluding NA). Two independent physician reviewers (SLZ and FTC) assessed the quality of reporting. Discrepancies in scoring were resolved with discussion between the two reviewers. Any unresolved discrepancies were decided by a third reviewer (EM).

Table 1.

CONSORT 2010 Checklist and percentage of articles that adequately report each CONSORT 2010 checklist item

| Title and abstract | ||

| 1a | Identification as a randomised trial in the title | 30.3% (23/33) |

| 1b | Structured summary of trial design, methods, results and conclusions (for specific guidance, see CONSORT for abstracts) | 9.1% (3/33) |

| Introduction | ||

| Background and objectives | ||

| 2a | Scientific background and explanation of rationale | 93.9% (31/33) |

| 2b | Specific objectives or hypotheses | 87.9% (29/33) |

| Methods | ||

| Trial design | ||

| 3a | Description of trial design (such as parallel, factorial) including allocation ratio | 42.4% (14/33) |

| 3b | Important changes to methods after trial commencement (such as eligibility criteria), with reasons | 100% (6/6) |

| Participants | ||

| 4a | Eligibility criteria for participants | 97% (32/33) |

| 4b | Settings and locations where the data were collected | 21.2% (7/33) |

| Interventions | ||

| 5 | The interventions for each group with sufficient details to allow replication, including how and when they were actually administered | 78.8% (26/33) |

| Outcomes | ||

| 6a | Completely defined prespecified primary and secondary outcome measures, including how and when they were assessed | 66.7% (22/33) |

| 6b | Any changes to trial outcomes after the trial commenced, with reasons | NA (0/0)* |

| Sample size | ||

| 7a | How sample size was determined | 69.7% (23/33) |

| 7b | When applicable, explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines | 100% (4/4) |

| Randomisation | ||

| Sequence generation | ||

| 8a | Method used to generate the random allocation sequence | 33.3% (11/33) |

| 8b | Type of randomisation; details of any restriction (such as blocking and block size) | 33.3% (11/33) |

| Allocation concealment mechanism | ||

| 9 | Mechanism used to implement the random allocation sequence (such as sequentially numbered containers), describing any steps taken to conceal the sequence until interventions were assigned | 12.1% (4/33) |

| Implementation | ||

| 10 | Who generated the random allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, and who assigned participants to interventions | 21.2% (7/33) |

| Blinding | ||

| 11a | If done, who was blinded after assignment to interventions (for example, participants, care providers, those assessing outcomes) and how | 32.3% (10/31) |

| 11b | If relevant, description of the similarity of interventions | 34.5% (10/29) |

| Statistical methods | ||

| 12a | Statistical methods used to compare groups for primary and secondary outcomes | 97.0% (32/33) |

| 12b | Methods for additional analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses | 77.8% (14/18) |

| Results | ||

| Participant flow | ||

| 13a | For each group, the numbers of participants who were randomly assigned, received intended treatment, and were analysed for the primary outcome | 66.7% (22/33) |

| 13b | For each group, losses and exclusions after randomisation, together with reasons | 65.6% (21/32) |

| Recruitment | ||

| 14a | Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up | 45.5% (15/33) |

| 14b | Why the trial ended or was stopped | 12.1% (4/33) |

| Baseline data | ||

| 15 | A table showing baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for each group | 90.9% (30/33) |

| Numbers analysed | ||

| 16 | For each group, number of participants (denominator) included in each analysis and whether the analysis was by original assigned groups | 54.5% (18/33) |

| Outcomes and estimation | ||

| 17a | For each primary and secondary outcome, results for each group, and the estimated effect size and its precision (such as 95% confidence interval) | 39.4% (13/33) |

| 17b | For binary outcomes, presentation of both absolute and relative effect sizes is recommended | 0.0% (0/7) |

| Ancillary analyses | ||

| 18 | Results of any other analyses performed, including subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses, distinguishing prespecified from exploratory | 68.8% (11/16) |

| Harms | ||

| 19 | All important harms or unintended effects in each group (for specific guidance, see CONSORT for harms) | 53.1% (17/32) |

| Discussion | ||

| Limitations | ||

| 20 | Trial limitations, addressing sources of potential bias, imprecision, and, if relevant, multiplicity of analyses | 78.8% (26/33) |

| Generalisability | ||

| 21 | Generalisability (external validity, applicability) of the trial findings | 87.9% (29/33) |

| Interpretation | ||

| 22 | Interpretation consistent with results, balancing benefits and harms, and considering other relevant evidence | 97.0% (32/33) |

| Other information | ||

| Registration | ||

| 23 | Registration number and name of trial registry | 48.5% (16/33) |

| Protocol | ||

| 24 | Where the full trial protocol can be accessed, if available | 100.0% (13/13) |

| Funding | ||

| 25 | Sources of funding and other support (such as supply of drugs), role of funders | 36.4% (12/33) |

Statistical analysis

Interobserver analysis scores were assessed for correlation using Cohen's κ score. Pearson's product–moment correlation was used to assess the correlation between CONSORT score and prespecified variables (journal impact factor, journal 5-year impact factor, article influence, eigenfactor, year of publication, author number, participant number and trial length). Mann-Whitney U test was used to test for binary non-parametric data. Journal metrics were obtained from InCites Journal Citation Reports.12 Risk of bias for each study was not analysed. Statistical analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics V.22 and Microsoft Excel 2011.

Results

Study search results and interobserver variability

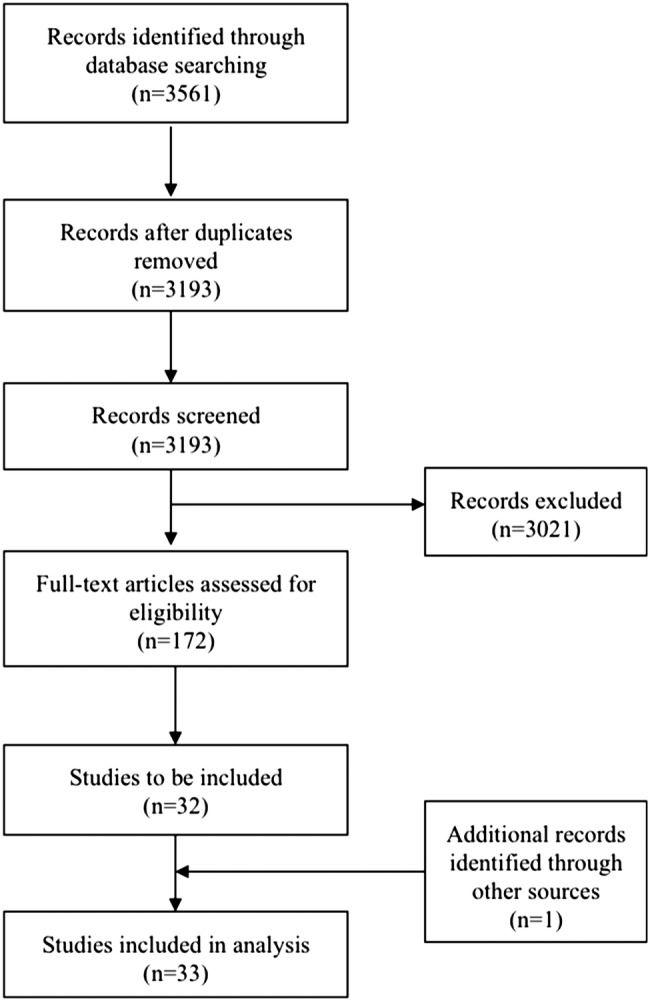

Initial search identified 3561 potential studies (MEDLINE n=1128, EMBASE n=1442, CENTRAL n=991). After the removal of duplicates and non-relevant articles, the full texts of 172 articles were reviewed (figure 1). The reference list of included articles and systematic review articles was searched for additional trials, identifying one other study. In total, 33 studies were included for analysis (see online supplementary material table S2 for study summary). Cohen's κ score for interobserver variability of CONSORT checklist scoring was 0.86 (91.3% observed agreement, 1115 of 1221 items).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study search, selection, inclusion and exclusion of articles.

Reporting quality

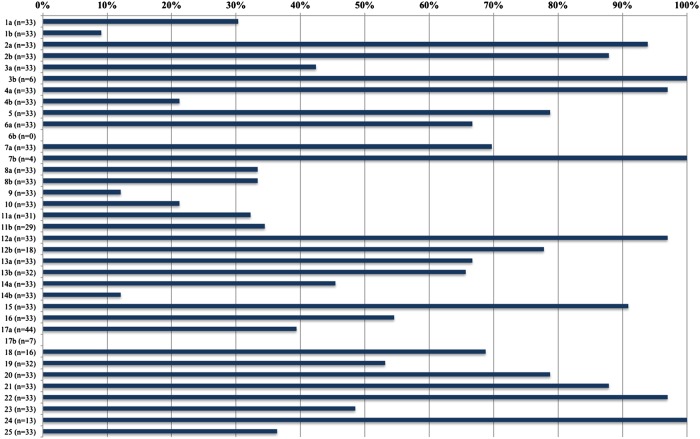

The mean article CONSORT score was 55.4% (range 23.3–93.8%, SD 17.2%; figure 2 and table 1). No article scored 100%. The best reported criteria were: protocol (item 24, 100%, 13/13), changes to methodology (item 3b, 100%, 6/6), interim analysis (item 7b, 100%, 4/4), interpretation (item 22, 97%, 32/33), eligibility criteria (item 4a, 97%, 32/33), statistical methods (item 12a, 97.0%, 32/33), background (item 21, 93.9%, 31/33) and baseline data (item 15, 90.9%, 30/33; figure 2 and table 1). The worst reported criteria were presentation of binary outcomes (item 17b, 0%, 0/7), abstract (item 1b, 9.1%, 3/33), trial termination (item 14b, 12.1% 4/33) and allocation concealment (item 9, 12.1%, 4/33).

Figure 2.

Percentage of studies adequately reporting each CONSORT 2010 checklist item where applicable.

Time trend and CONSORT statement updates

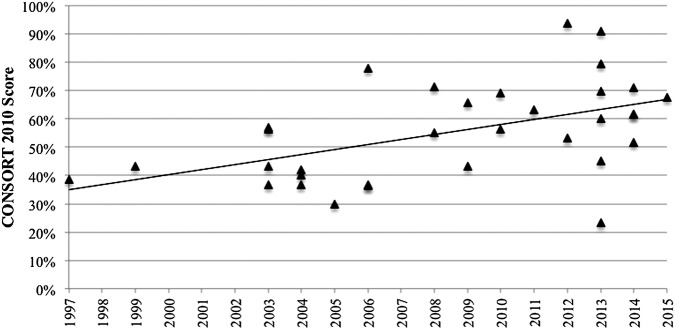

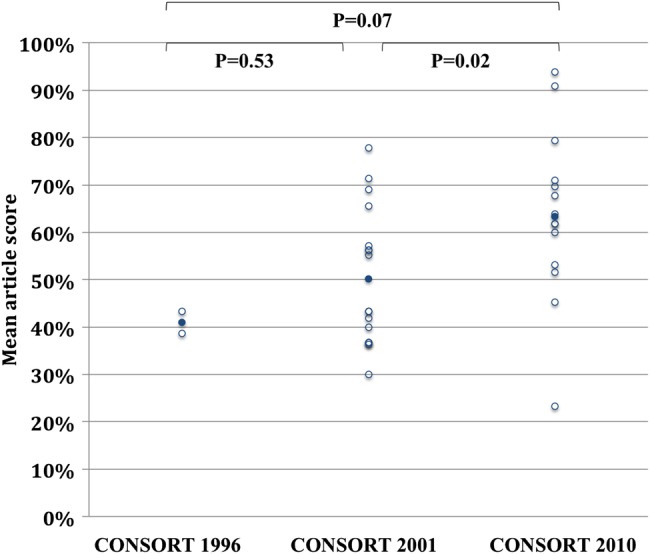

The CONSORT 2010 score increased with time and showed strong correlation with the year of publication (r=0.50, p=0.003; figure 3). Articles published after the CONSORT 1996 statement but before the CONSORT 2001 update had a mean score of 41.0% (SD 3.3%; figure 4). Articles published between CONSORT 2001 and CONSORT 2010 had a mean score of 50.2% (SD 14.5%). Articles published after CONSORT 2010 had a mean score of 63.8% (SD 18.1%). There was a significant increase in the mean score of articles published after CONSORT 2010 compared with those published between CONSORT 2001 and 2010 (difference between means 13.6%, p=0.02), whereas the difference between CONSORT 1996 and 2010 scores approached significance (difference between means 22.8%, p=0.07). There was no significant difference between CONSORT 1996 and 2001 scores (difference between means 9.2%, p=0.53).

Figure 3.

The year of publication and CONSORT 2010 score.

Figure 4.

Individual study CONSORT 2010 score grouped by latest CONSORT statement at the time of publication. Individual study CONSORT 2010 score (open circles) grouped by available CONSORT statement (1996, 2001 and 2010) at the time of study publication, with mean scores during each period (filled circles).

Correlation with journal impact factor

The CONSORT score was strongly correlated with journal impact factor (r=0.53, p=0.003) and journal 5-year impact factor (r=0.49, p=0.006). The score was also strongly correlated with article influence score (r=0.50, p=0.005) and with eigenfactor score (r=0.36, p=0.05).

Correlation with other variables

The CONSORT score was strongly correlated with author number (r=0.52, p=0.002) but not with participant number (r=0.30, p=0.09) or treatment duration (r=0.17, p=0.34). Trials that included ≥100 patients had a higher CONSORT score (63.7% vs. 46.5%, p=0.011). There was no significant difference for treatment duration (≥12 m or <12 m), trial assignment (parallel or crossover) or funding sponsor (national/charity/academic or pharmaceutical company/industry; table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of trial characteristics on CONSORT score

| Variable | Mean score (SD) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment duration | ||

| <12 m (n=21) | 53.1% (17.8%) | NS |

| ≥12 m (n=12) | 59.4% (16.1%) | |

| Participant number | ||

| <100 (n=16) | 46.5% (13.5%) | 0.011 |

| ≥100 (n=17) | 63.7% (16.4%) | |

| Primary end point result | ||

| Positive | 57.5% (19.6%) | NS |

| Negative | 52.7% (15.5%) | |

| Centres | ||

| Single centre (n=14) | 48.0% (14.0%) | NS |

| Multicentre (n=10) | 57.3% (19.0%) | |

| International multicentre (n=9) | 64.8% (16.2%) | |

| Assignment | ||

| Parallel (n=5) | 49.1% (20.1%) | NS |

| Crossover (n=28) | 56.5% (16.8%) | |

| Funding/sponsor | ||

| National, charity, academic (n=18) | 56.5% (15.4%) | NS |

| Pharmaceutical company, industry (n=15) | 59.2% (17.0%) | |

Reporting quality of Methods and Results

The mean reporting score for the Methods section (checklist items 3a–12b) was 51.9% (range 15.4–92.9%, SD 19.7%) and that for the Results section (checklist items 13a–19) was 51.9% (range 12.5–100%, SD 24.1%). There remained correlation with the year of publication and journal's impact factor (Methods: r=0.32 and r=0.36; Results: r=0.39 and r=0.51; combined methods and results: r=0.38 and r=0.47), which was not significantly different from correlation coefficient of total score with the year of publication (p>0.20 for all). Mean scores for Methods and Results increased after CONSORT 2010 publication from 42.5% to 61.9% and 44.1% to 59.3%, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we have systematically identified all RCTs investigating the efficacy of pharmacological interventions in HFpEF and have, for the first time, comprehensively assessed the reporting quality of these publications. We show a trend in improving reporting quality of HFpEF RCTs over time and following updates to CONSORT guidelines, though there remains a considerable variation in reporting quality, with many important aspects relating to trial methodology and results consistently under-reported. The mean CONSORT 2010 score for HFpEF RCTs is 55.4%, comparable to the findings from similar contemporary studies in other fields of medicine and surgery.13–17 We also identified a strong positive correlation between the CONSORT score and metrics of journal impact and author number.

Critical appraisal of the validity and generalisability of study findings requires comprehensive reporting of clinical trials, with discrepancies associated with variations in effect estimate that may affect management decisions by doctors and policymakers. Although several criteria were well reported, we identified significant deficiencies in trial methodology and reporting of results. These have impact on readers' assessments of study quality and risk of bias, and will reduce the quality and accuracy of meta-analyses. Similar reviews have echoed these findings, highlighting particularly poor reporting of details surrounding randomisation.2 14–18 Chen and Liu2 showed that the reporting of methodology in RCTs in a high impact cardiology journal was inadequate, with 70% of studies reporting less than half of methodological items sufficiently, with randomisation and blinding frequently affected.

The CONSORT 2010 score demonstrates positive correlation with the year of publication, with articles published after 2010 scoring more favourably than those from earlier periods. The CONSORT update in 2010 is likely to have generated increased awareness of the importance of high reporting standards. A Cochrane review in 2012 demonstrating superior reporting quality of articles published by journals that endorse CONSORT guidelines compared with those that did not, and improvements after a journal's endorsement of CONSORT.19 Accordingly, almost 600 biomedical journals, including Open Heart, endorse CONSORT and advise adherence from submitting authors.20

We demonstrate positive correlation between measures of journal impact with CONSORT score. Although authors will aim to submit the most thoroughly reported studies to the most influential publishers, higher impact factor journals have higher rejection rates and will therefore impose more rigorous presubmission checks and review processes. Furthermore, better-reported studies may be more extensively cited, with a corresponding positive influence on journal impact factor.

Significance of reporting quality in HFpEF clinical trials

As in all conditions with uncertain therapies, the meta-analysis of pooled trial and registry data are important in increasing our understanding of possible treatments for HFpEF. High-quality meta-analysis depends on comprehensive and accurate trial information, with particular emphasis on the population, intervention and outcome measures, and trial design. Although there have been many recent meta-analyses of specific drug classes in HFpEF,21–23 the last comprehensive review for all drug therapies in HFpEF was published in 2011 and identified no reduction in all-cause mortality for drug classes, individually and combined.24 Since then, there have been a large number of new trials—including at least 14 RCTs identified in this study—some of which have evaluated novel treatments and there is value in including these in an updated review.25

Detailed reporting of study inclusion criteria and participant demographics are particularly important in HFpEF clinical trials. Trial inclusion criteria are heterogeneous and have changed as the understanding of HFpEF as a disease syndrome has evolved.26 Combinations of LVEF cut-offs, prior heart failure hospitalisation, clinical features, the presence or absence of comorbidities, echocardiographic and haemodynamic parameters, and natriuretic peptide levels are being used as inclusion criteria. In a recent analysis comparing three major HFpEF trials (the Digitalis Investigation Group-Preserved Ejection Fraction (DIG-PEF), Candesartan in Heart Failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM-Preserved) and Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved systolic function (I-PRESERVE)), the authors found that the I-PRESERVE study population was most representative of HFpEF patients in the community, possibly attributable to its comparatively stringent inclusion criteria.27 Although strict inclusion criteria is likely to reduce the recruitment of patients with LV systolic dysfunction, exclusion of significant comorbidities may result in a non-representative study population and reduce the applicability of results to real-life settings. Analysing the effects that patient selection criteria have on published trial outcomes will be important in optimising future trial design.

The pathophysiological role of non-cardiac comorbidities in patients with HFpEF is becoming well characterised and better understood.28 29 HFpEF populations demonstrate a high prevalence of pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus and cardiometabolic disorders, anaemia, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and obesity30–32 and are independently associated with poor outcomes.33–36 The distribution of such comorbidities in clinical trials is likely to influence results, and indeed it has been argued that the absence of positive outcomes may be related to inclusion of non-HFpEF patients.37 Although patient demographics were well reported (91% of all trials), detailed description of important comorbidities was much poorer: diabetes mellitus was reported in 70% of trials, atrial fibrillation in 52%, COPD in 18%, anaemia in 9%, CKD in 9% and obesity in 6%. This shows that while adherence to reporting standards is to be encouraged, it is important that salient information of particular interest in HFpEF should be provided.

It is increasingly accepted that HFpEF is a heterogeneous condition with a range of disease phenotypes. Using the novel approach of latent class analysis (LCA), Kao et al38 used patients enrolled in the I-PRESERVE study and identified a significant positive response to irbesartan compared with placebo in a group characterised by high prevalence of obesity, diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidaemia. Although LCA is one approach that can identify subgroups with differing prognoses and responses to treatments, this requires patient-level data that can be challenging to access.39 Consequently, there is strength in combining individual trial subgroup analyses using meta-analysis. This approach of investigating treatment effects on different patient groups stratified by variables will likely yield insight into which groups are likely to respond to therapy. The ability and success of this approach depends on the clear reporting of all prespecified analyses and primary and secondary outcomes, including subgroup analyses and exploratory outcomes. A review of heart failure disease-management programmes found that significant and clinically important differences within subgroups are not meta-analysed due to a dearth of available reported data,40 a finding that is likely to be true for HFpEF. Similarly, another group undertaking meta-analysis of the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments in patients with NYHA class I or II symptoms were unable to do so due to poor reporting and non-disclosure of data.39

Important aspects of HFpEF trial design can influence outcomes and the investigators' ability to detect differences.41 As demonstrated in the Perindopril in Elderly People with Chronic Heart Failure (PEP-CHF) study, the primary end point of all-cause mortality and unplanned heart failure hospitalisation trended towards statistical significance at 12 months (HR 0.69, p=0.055). However, these beneficial effects were lost by the end of the trial (HR 0.92, p=0.545). This was due to a significant proportion of patients in the placebo arm going onto open-label ACEi, resulting in an eventual study power of just 35%. The CHARM-preserved trial generated neutral results, though study-drug discontinuation for adverse events or laboratory abnormalities was significantly higher in the treatment arm than in the placebo arm (18% vs 14%, p=0.001). The use of a run-in period to establish drug tolerance may reduce the differential effects of study drug discontinuation. Although trial results have been largely neutral, it cannot be conclusively argued that perindopril, candesartan or other HFpEF trial treatments are of no clinical benefit, as trial design and limitations can clearly affect the ability of studies to detect meaningful differences and must therefore be clearly reported.

Geographic variation in the rates of mortality and hospitalisation in HFpEF clinical trials has been well described.42 In the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function with Aldosterone Antagonist Trial (TOPCAT), the primary end point rate was far lower in Russia and Georgia (unadjusted rate of 2.3 per 100 patient-years in placebo group) than in the Americas (12.6 per 100 patient-years).43 Similar results were found for the CHARM-Preserved and I-PRESERVE trials, with unadjusted rates of mortality, and adjusted rates for hospitalisation for heart failure greater in North America compared with Eastern Europe and Russia.42 This variation is more specific for trials of HFpEF rather than trials of HFrEF and may reflect the logistical challenges and disparate criteria for diagnosing HFpEF, or differing provision of healthcare services available.42 Regional variations in outcome rates are an important consideration in international, multicentre RCTs, with clear reporting of trial centre locations and number of patients enrolled, event rates by regional area and subgroup analysis by region all important in understanding the influence that geographical variation has on treatment outcomes.

Study limitations

One limitation of our study methods is that the outcome measure, CONSORT 2010 score, requires subjective assessment. Publications from CONSORT provide good guidance on this,1 and scoring was carried out blindly by two assessors in this study. We showed a high degree of interobserver agreement, comparable with other similar published studies, with all discrepancies resolved by discussion. The use of ‘N/A’ as an additional qualifier protects studies against falsely low scores, by only scoring articles out of a relevant total. It must be emphasised that a study's CONSORT score does not reflect the quality of the study or its risk of bias. Rather, high-quality reporting is necessary for accurate meta-analysis, trial evaluation to aid interpretation and implementation, and allows contributions to the wider body of work. One argument against the rigid use of CONSORT or its surrogate as a marker of article reporting quality is that certain aspects may be deemed to be unnecessary (eg, absolute risk difference may be easily calculated from the individual event rates), and indeed reviewers may ask for superfluous information to be removed. In our study, we are unable to discern whether failure to report a CONSORT item has occurred due to authors, editors or reviewers.

Conclusions

The reporting quality of RCTs investigating the impact of pharmacological interventions in HFpEF has improved over time but remains suboptimal. We identified a positive trend in the quality of reporting following each revision of the CONSORT statement and demonstrated correlation between the quality of study reporting and journal impact factor. Encouragingly, reporting of methodology and results increased significantly after the update of CONSORT in 2010. Although improvements in adherence to CONSORT 2010 reporting criteria are necessary, specific details related to inclusion criteria, patient demographics, trial design and subgroup analysis by important variables (participant demographics, comorbidities and geographical variation) will provide greater insight into treatment effects for HFpEF and lend a basis on which future clinical trials be designed. The treatment of HFpEF remains a substantial clinical challenge and, given the relatively small number of dedicated RCTs, transparent and complete reporting will likely improve our understanding of the disease and its treatments.

Footnotes

Contributors: SLZ, FTC and EM take full-responsibility as cofirst authors. SJ involved in data collection and drafting of the manuscript. AAN reviewed the manuscript. All authors approve the final manuscript, and account for the accuracy and integrity of the work.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c869 10.1136/bmj.c869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen HL, Liu K. Reporting in randomized trials published in International Journal of Cardiology in 2011 compared to the recommendations made in CONSORT 2010. Int J Cardiol 2012;160:208–10. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.06.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan AW, Altman DG. Epidemiology and reporting of randomised trials published in PubMed journals. Lancet 2005;365:1159–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71879-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c332 10.1136/bmj.c332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:e147–239. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD et al. Authors/Task Force Members, Document Reviewers. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. Published Online First: 20 May 2016. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Q, Chen Y, Liu Q et al. Effects of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors on mortality, hospitalization, and diastolic function in patients with HFpEF: a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials. Herz 2016;41:76–86. 10.1007/s00059-015-4346-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Wang H, Lu Y et al. Effects of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in patients with preserved ejection fraction: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMC Med 2015;13:10 10.1186/s12916-014-0261-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capuano A, Scavone C, Vitale C et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Int J Cardiol 2015;200:15–19. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.07.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu F, Chen Y, Feng X et al. Effects of beta-blockers on heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e90555 10.1371/journal.pone.0090555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deswal A, Richardson P, Bozkurt B et al. Results of the Randomized Aldosterone Antagonism in heart failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction trial (RAAM-PEF). J Card Fail 2011;17:634–42. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevanovic A, Schmitz S, Rossaint R et al. CONSORT item reporting quality in the top ten ranked journals of critical care medicine in 2011: a retrospective analysis. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0128061 10.1371/journal.pone.0128061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adie S, Harris IA, Naylor JM et al. CONSORT compliance in surgical randomized trials: are we there yet? A systematic review. Ann Surg 2013;258:872–8. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31829664b9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bearn DR, Alharbi F. Reporting of clinical trials in the orthodontic literature from 2008 to 2012: observational study of published reports in four major journals. J Orthod 2015;42:186–91. 10.1179/1465313315Y.0000000011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu LQ, Morris PJ, Pengel LH. Compliance to the CONSORT statement of randomized controlled trials in solid organ transplantation: a 3-year overview. Transpl Int 2013;26:300–6. 10.1111/tri.12034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camm CF, Chen Y, Sunderland N et al. An assessment of the reporting quality of randomised controlled trials relating to anti-arrhythmic agents (2002–2011). Int J Cardiol 2013;168:1393–6 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redfield MM, Chen HH, Borlaug BA et al. Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition on exercise capacity and clinical status in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;309:1268–77. 10.1001/jama.2013.2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner L, Shamseer L, Altman DG et al. Does use of the CONSORT Statement impact the completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials published in medical journals? A Cochrane review. Syst Rev 2012;1:60 10.1186/2046-4053-1-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CONSORT. Secondary. http://www.consort-statement.org/about-consort/endorsers

- 21.Bavishi C, Chatterjee S, Ather S et al. Beta-blockers in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev 2015;20:193–201. 10.1007/s10741-014-9453-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emdin CA, Callender T, Cao J et al. Meta-analysis of large-scale randomized trials to determine the effectiveness of inhibition of the renin-angiotensin aldosterone system in heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2015;116:155–61. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.03.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pandey A, Garg S, Matulevicius SA et al. Effect of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists on cardiac structure and function in patients with diastolic dysfunction and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Am Heart Assoc 2015;4:e002137 10.1161/JAHA.115.002137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holland DJ, Kumbhani DJ, Ahmed SH et al. Effects of treatment on exercise tolerance, cardiac function, and mortality in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. A meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:1676–86. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Lueder TG, Krum H. New medical therapies for heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015;12:730–40. 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly JP, Mentz RJ, Mebazaa A et al. Patient selection in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:1668–82. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell RT, Jhund PS, Castagno D et al. What have we learned about patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction from DIG-PEF, CHARM-preserved, and I-PRESERVE? J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:2349–56. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mentz RJ, Kelly JP, von Lueder TG et al. Noncardiac comorbidities in heart failure with reduced versus preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:2281–93. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paulus WJ, Tschope C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:263–71. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinberg BA, Zhao X, Heidenreich PA et al. Trends in patients hospitalized with heart failure and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: prevalence, therapies, and outcomes. Circulation 2012;126:65–75. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.080770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fonarow GC, Stough WG, Abraham WT et al. Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart failure: a report from the OPTIMIZE-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:768–77. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yancy CW, Lopatin M, Stevenson LW et al. Clinical presentation, management, and in-hospital outcomes of patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure with preserved systolic function: a report from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) database. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:76–84. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braunstein JB, Anderson GF, Gerstenblith G et al. Noncardiac comorbidity increases preventable hospitalizations and mortality among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1226–33. 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00947-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Felker GM, Shaw LK, Stough WG et al. Anemia in patients with heart failure and preserved systolic function. Am Heart J 2006;151:457–62. 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacDonald MR, Petrie MC, Varyani F et al. Impact of diabetes on outcomes in patients with low and preserved ejection fraction heart failure: an analysis of the Candesartan in Heart failure: assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) programme. Eur Heart J 2008;29:1377–85. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith DH, Thorp ML, Gurwitz JH et al. Chronic kidney disease and outcomes in heart failure with preserved versus reduced ejection fraction: the Cardiovascular Research Network PRESERVE Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013;6:333–42. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perez-Calvo JI, Montero-Perez-Barquero M, Formiga F. Diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: still a challenge. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1748–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kao DP, Lewsey JD, Anand IS et al. Characterization of subgroups of heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction with possible implications for prognosis and treatment response. Eur J Heart Fail 2015;17:925–35. 10.1002/ejhf.327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fleetcroft R, Ford J, Gollop ND et al. Difficulty accessing data from randomised trials of drugs for heart failure: a call for action. BMJ 2015;351:h5002 10.1136/bmj.h5002published [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clark AM, Savard LA, Thompson DR. What is the strength of evidence for heart failure disease-management programs? J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:397–401. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Becher PM, Fluschnik N, Blankenberg S et al. Challenging aspects of treatment strategies in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: “Why did recent clinical trials fail?”. World J Cardiol 2015;7:544–54 10.4330/wjc.v7.i9.544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kristensen SL, Kober L, Jhund PS et al. International geographic variation in event rates in trials of heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. Circulation 2015;131:43–53. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF et al. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1383–92. doi:0.1056/NEJMoa1313731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

openhrt-2016-000449supp.pdf (453.1KB, pdf)