Abstract

Primers specific for Escherichia coli O15:K52:H1 were devised based on a novel single-nucleotide polymorphism identified within the housekeeping gene fumC, i.e., G594A. In experiments comparing various reference typing methods, the new primers provided 100% sensitivity and specificity for the O15:K52:H1 clonal group, including 162 diverse clinical and reference E. coli isolates.

The O15:K52:H1 clonal group of Escherichia coli is a globally distributed extraintestinal pathogen, often associated with multi-antimicrobial drug resistance (7, 13, 15, 17, 18, 20, 21). It first gained notoriety during a community-wide outbreak of drug-resistant urinary tract infections in London, England, in 1986-1987 (18, 20). It subsequently was identified among blood isolates in Copenhagen and urine and blood isolates in Spain (15, 17, 21), where in comparison with other E. coli isolates, it more often infected younger hosts and caused pyelonephritis (21). A recent survey showed it to be broadly distributed across the U.S. and to preferentially infect humans over animals (13).

Combined resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfonamides, tetracycline, and trimethoprim has characterized the O15:K52:H1 clonal group since its first appearance. Additionally, fluoroquinolone resistance has been detected among isolates from Spain and Iowa (7, 13, 21). This increases the clinical importance of the O15:K52:H1 clonal group and indicates a need for further molecular epidemiological studies.

To date, identification of the O15:K52:H1 clonal group has relied on O:K:H serotypes or PCR-based genomic profiles as generated by repetitive-element PCR or random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis (7, 13, 17, 20, 21). Unfortunately, O:K:H serotyping is not generally available, and PCR-based fingerprinting methods suffer from run-to-run, cycler-to-cycler, and interlaboratory variability (3, 9, 23) and subjective interpretation (2, 22, 24). A more reproducible, objective, and portable diagnostic test for this clonal group is needed. Accordingly, we sought to develop a gene-specific PCR assay for rapid and specific detection of the O15:K52:H1 clonal group, analogous to the recently devised fumC-based PCR assay for E. coli clonal group A (CGA) (11).

Sequence analysis and primer design.

Reference strains for the O15:K52:H1 clonal group included E. coli 29/P (isolated from urine from Barcelona, Spain) (21) and 2P9 (isolated from a urosepsis patient from Seattle, Wash.) (13). Comparison isolates for sequence analysis (number of isolates, 32) included representatives of several other recognized extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) clonal groups, including E. coli CGA (8, 14), plus selected members of the E. coli Reference (ECOR) collection (16) representing all four major E. coli phylogenetic groups (A, B1, B2, and D) and the ungrouped ECOR strains (4). A partial coding sequence (469 bp) for fumC was determined bidirectionally by using internal primers (11). Sequences were aligned by using CLUSTAL-X. Trees constructed according to various phylogenetic methods consistently paired the two O15:K52:H1 reference strains as a strongly supported discrete clade that had ECOR strain 44 (phylogenetic group D) as its nearest neighbor and the CGA clade as its next nearest neighbor (11).

One putative O15:K52:H1-specific single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) was identified, i.e., fumC G594A. A reverse primer with this SNP at its 3′ terminus (5′-CCGGAAATCTCCTGT-3′, bp 608 to 594) was paired with a forward primer based on an upstream consensus fumC region (5′-GCTGCTGGCGCTGCGCAAGCAA-3′, bp 456 to 473) and used in PCR with known positive and negative controls.

PCR conditions.

Boiled lysates were used as template DNA (12). Amplification was done using 25-μl reaction products containing a 0.6 μM concentration of each primer, 0.8 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Sigma), 4 mM MgCl2 (Applied Biosystems), 1× commercial buffer, 1.25 U of thermally activated Taq polymerase (Applied Biosystems), and 2 μl of template DNA. The cycling protocol consisted of the following: 95°C for 10 min, then 25 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 63°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 3 min, and then 72°C for 10 min. To assess the assay stability, PCR was done with various concentrations of each ingredient and at annealing temperatures from 59 to 67°C.

RAPD analysis.

Isolates were defined as O15:K52:H1 if their genomic profiles (8, 14) were indistinguishable from those of the O15:K52:H1 reference strains according to RAPD analysis using one or more of five primers, selected from among decamers 1247, 1254, 1281, 1283, and 1290 (1).

Primer validation.

The new fumC primers were tested against 162 E. coli isolates, including 51 putative O15:K52:H1 isolates from diverse locales and 111 putative non-O15:K52:H1 isolates. The latter group comprised geographically and phylogenetically diverse clinical isolates and ECOR strains, including representatives of all four E. coli phylogenetic groups and multiple representatives of CGA (Table 1). The predicted 153-bp band was obtained, in duplicate, with 45 of the 51 positive control strains (estimated sensitivity, 88%) but with none of the 111 negative controls (estimated specificity, 100%).

TABLE 1.

Validation of the O15:K52:H1-specific fumC PCR assay for 162 E. coli isolates of known clonal group status

| Isolate source(s) | Putative O15:K52:H1 clonal group status (no.)b

|

Basis for assignmentc |

fumC PCR assay result (no.)

|

Commentd | Reference(s) or source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos. | Neg. | Pos. | Neg. | ||||

| Spain, England (urine) | 25 | O:K:H serotype | 22 | 3 | All 3 isolates neg. by PCR assay were non-O15:K52:H1 by RAPD and MLST; 2 were K− or Knt | 21 | |

| 15 | O:K:H serotype | 0 | 15 | 21 | |||

| U.S., Africa (all O15 isolates) | 18 | RAPD, ERIC, BOX | 15 | 3 | All 3 isolates neg. by PCR assay were positive for F7-2 and hly and non-O15:K52:H1 by RAPD (one also by MLST); two were serotyped as O15:K2:H18 | 13 | |

| 18 | RAPD, ERIC, BOX | 0 | 18 | 13 | |||

| Iowa clin. micro. labsa | 7 | RAPD, O15 antigen | 7 | 0 | All isolates resistant to ciprofloxacin | 7 | |

| ECOR collection | 13 | O antigen, phylo. gp. | 0 | 13 | ECOR strains 7, 10, 24, 30, 35, 40, 41, 44, 47, 50, 59, 62, 72 | 5,17 | |

| Pyelonephritis (U.S.) | 1 | O antigen, RAPD | 1 | 0 | 8 | ||

| 20 | O antigen, RAPD | 0 | 20 | 8 | |||

| Cystitis (Minn.) | 8 | O antigen | 0 | 8 | 14 | ||

| Global CGA search | 24 | Phylo. gp., RAPD | 0 | 23 | Abstractf | ||

| CGA in acute cystitis | 18 | ERIC, RAPD, PFGE | 0 | 18 | 14 | ||

| Total | 51 | 111 | 45 | 117 | PCR assay sensitivitye 88% (or 100%); specificity, 100% | ||

Clin. micro. labs, clinical microbiology laboratories.

Pos., positive; neg., negative.

ERIC and BOX, ERIC2 and BOX A1R repetitive-element fingerprinting; phylo. gp., phylogenetic group; PFGE, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

MLST, multilocus sequence typing; K−, capsule minus; Knt, K nontypeable; F7-2, papA variant (P fimbrial structural subunit); hly, hemolysin gene.

Estimated sensitivity depends on whether the seven false-negative fumC reference isolates are regarded as O15:K52:H1 (see the text).

A. C. Murray, T. T. O'Bryan, M. A. Kuskowski, A. R. Manges, L. W. Riley, and J. R. Johnson. Abstr. 103rd Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol.

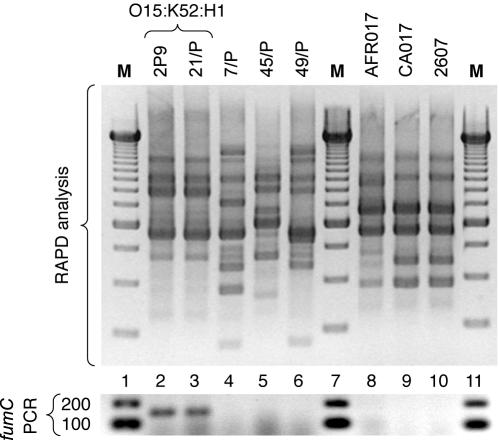

Further analysis of the six putative O15:K52:H1 isolates that yielded negative fumC PCR results demonstrated that none were actually O15:K52:H1 clonal group members. According to RAPD analysis (Fig. 1) and fumC sequence analysis (data not shown), three of the isolates proved to be members of a distinct clonal group which, according to published data (13), exhibits the K2 capsular and H18 flagellar antigens, the F7-2 papA allele (rather than F16), and hly (the hemolysin gene; absent from O15:K52:H1 strains) (Table 1). Three others, including one that could not be confirmed as O15 and two that were previously serotyped as K− and K nontypeable (21), proved to be of diverse (including non-group D) phylogenetic backgrounds. Reclassification of these six isolates as non-O15:K52:H1 improved the fumC assay's estimated accuracy to 100% (100% sensitivity and 100% specificity) (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

RAPD profiles and fumC PCR results for confirmed and putative representatives of E. coli O15:K52:H1. (Top) RAPD profiles as generated using arbitrary decamer 1247 (1). (Bottom) fumC PCR assay results for same isolates. Lane numbers are shown between top and bottom images. Lanes: 2 and 3, O15:K52:H1 reference isolates 2P9 (Seattle, Wash.) (13) and 21/P (Barcelona, Spain) (21); 4-6, putative O15:K52:H1 clonal group members from Spain (21); 8-10, non-European putative O15:K52:H1 clonal group members (13). Strains CA017 and 2607 (lanes 8 and 9) exhibited serotype O15:K2:H18 according to the International Escherichia and Klebsiella Centre (World Health Organization), Statens Seruminstitut, Copenhagen, Denmark (13). Strain AFR017 (lane 10) was O15:H untypeable according to the E. coli Reference Center, University Park, Pa. (13). Sizes shown for marker bands are in base pairs. M, 250-bp ladder (top) and 100-bp ladder (bottom) (Gibco).

Stability and portability of assay.

In the primary laboratory (the laboratory of J.R.J.), halving and doubling the concentrations of all reaction mixture components (individually) and varying the annealing temperature from 59 to 65°C had negligible effects on assay results (data not shown). At an annealing temperature of 67°C, no product was obtained.

In a separate laboratory (the laboratory of G.P.), the assay was carried out successfully using newly synthesized primers, separate reagents (deoxynucleoside triphosphates from Roche and polymerase from Bioline), and new lysates. However, an annealing temperature of 58°C was required to obtain a consistent fumC amplicon. Of 24 reference isolates tested, including 16 putative O15:K52:H1 representatives and eight non-O15:K52:H1 strains, 23 (96%) yielded results identical to those obtained in the primary laboratory. The single discrepancy proved to represent a strain substitution, the correction of which resolved the conflict.

Significance.

The O15:K52:H1-specific primers we selected based on a newly identified SNP within fumC (G594A) detected clonal group members with extreme precision within a large and phylogenetically diverse strain set. The assay was simple, tolerated diverse PCR conditions, and yielded concordant results between laboratories. It thus should make unambiguous and reproducible detection of the O15:K52:H1 clonal group available to any laboratory, without the well-recognized pitfalls of PCR-based fingerprinting methods (2, 3, 9, 22-24).

This study extends our prior work regarding the identification of ExPEC clonal groups using gene-specific PCR assays based on distinctive SNPs within presumably selection-neutral housekeeping genes (11). Conceivably, this strategy could be applied to the detection of any E. coli clonal group of interest (6, 10, 19).

Interestingly, the assay identified as non-O15:K52:H1 several isolates that previously were classified as O15:K52:H1. Three of these isolates were known to exhibit distinctive K:H serotypes and/or virulence profiles, which previously had been interpreted as reflecting novel antigenic and pathotypic diversity within the O15:K52:H1 clonal group (13). Reassessment of these isolates by using RAPD fingerprinting and fumC sequence analysis showed them to be highly homogeneous yet distinct from orthodox O15:K52:H1 reference strains. This showed that they represent a novel O15:K2:H18 clonal group, which confirmed the validity of the O15:K52:H1 fumC PCR assay's negative result. The other three isolates with putatively false-negative fumC PCR results also proved to represent misclassification errors (13, 21).

Why the assay required a lower annealing temperature in one laboratory than in the other is unclear. Undefined differences in the reagents, which were from different suppliers, or other technical aspects of the assay may have contributed. Assay optimization may be required when the fumC PCR assay is established in a new laboratory.

In summary, we have devised and validated a PCR assay, based on an SNP within fumC (G594A), that provides rapid and specific detection of the epidemic and antimicrobial resistance-associated O15:K52:H1 clonal group of E. coli. The new assay should facilitate future studies regarding the prevalence, distribution, ecology, and epidemiology of this intriguing and enigmatic ExPEC clonal group.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs; the Minnesota Department of Health; and National Research Initiative (NRI) Competitive Grants Program/United States Department of Agriculture grant 00-35212-9408.

Dave Prentiss (Minneapolis VA Medical Center) prepared the figure. Timothy T. O'Bryan provided expert technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berg, D. E., N. S. Akopyants, and D. Kersulyte. 1994. Fingerprinting microbial genomes using the RAPD or AP-PCR method. Methods Mol. Cell. Biol. 5:13-24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burr, M. D., and I. L. Pepper. 1997. Variability in presence-absence scoring of AP PCR fingerprints affects computer matching of bacterial isolates. J. Microbiol. Methods 29:63-68. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellsworth, D. L., K. D. Rittenhouse, and R. L. Honeycutt. 1993. Artifactual variation in randomly amplified polymorphic DNA banding patterns. BioTechniques 14:214-217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herzer, P. J., S. Inouye, M. Inouye, and T. S. Whittam. 1990. Phylogenetic distribution of branched RNA-linked multicopy single-stranded DNA among natural isolates of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 172:6175-6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson, J. R., P. Delavari, M. Kuskowski, and A. L. Stell. 2001. Phylogenetic distribution of extraintestinal virulence-associated traits in Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 183:78-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson, J. R., P. Delavari, and T. O'Bryan. 2001. Escherichia coli O18:K1:H7 isolates from acute cystitis and neonatal meningitis exhibit common phylogenetic origins and virulence factor profiles. J. Infect. Dis. 183:425-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson, J. R., M. A. Kuskowski, K. Owens, A. Gajewski, and P. L. Winokur. 2003. Phylogenetic origin and virulence genotype in relation to resistance to fluoroquinolones and/or extended spectrum cephalosporins and cephamycins among Escherichia coli isolates from animals and humans. J. Infect. Dis. 188:759-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson, J. R., A. R. Manges, T. T. O'Bryan, and L. R. Riley. 2002. A disseminated multi-drug resistant clonal group of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli as a cause of pyelonephritis. Lancet 359:2249-2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson, J. R., and T. T. O'Bryan. 2000. Improved repetitive-element PCR fingerprinting for resolving pathogenic and nonpathogenic phylogenetic groups within Escherichia coli. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 7:265-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson, J. R., T. T. O'Bryan, M. A. Kuskowski, and J. N. Maslow. 2001. Ongoing horizontal and vertical transmission of virulence genes and papA alleles among Escherichia coli blood isolates from patients with diverse-source bacteremia. Infect. Immun. 69:5363-5374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson, J. R., K. Owens, A. R. Manges, and L. W. Riley. 2004. Rapid and specific detection of Escherichia coli clonal group A by gene-specific PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2618-2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson, J. R., and A. L. Stell. 2000. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J. Infect. Dis. 181:261-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson, J. R., A. L. Stell, T. T. O'Bryan, M. Kuskowski, B. Nowicki, C. Johnson, J. M. Maslow, A. Kaul, J. Kavle, and G. Prats. 2002. Global molecular epidemiology of the O15:K52:H1 extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli clonal group: evidence of distribution beyond Europe. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1913-1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manges, A. R., J. R. Johnson, B. Foxman, T. T. O'Bryan, K. E. Fullerton, and L. W. Riley. 2001. Widespread distribution of urinary tract infections caused by a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli clonal group. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:1007-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirelis, B., E. Miro, F. Navarro, C. A. Ogalla, J. Bonal, and G. Prats. 1993. Increased resistance to quinolones in Catalonia, Spain. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 16:137-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ochman, H., and R. K. Selander. 1984. Standard reference strains of Escherichia coli from natural populations. J. Bacteriol. 157:690-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olesen, B., H. J. Kolmos, F. Orskov, and I. Orskov. 1995. A comparative study of nosocomial and community-acquired strains of Escherichia coli causing bacteraemia in a Danish university hospital. J. Hosp. Infect. 31:295-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Neill, P. M., C. A. Talboys, A. P. Roberts, and B. S. Azadian. 1990. The rise and fall of Escherichia coli O15 in a London teaching hospital. J. Med. Microbiol. 33:23-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orskov, I., F. Orskov, A. Birch-Andersen, M. Kanamori, and C. Svanborg Eden. 1982. O, K, H and fimbrial antigens in Escherichia coli serotypes associated with pyelonephritis and cystitis. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 33:18-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips, I., S. Eykyn, A. King, W. R. Grandsden, B. Rowe, J. A. Frost, and R. J. Gross. 1988. Epidemic multiresistant Escherichia coli infection in West Lambeth health district. Lancet i:1038-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prats, G., F. Navarro, B. Mirelis, D. Dalmau, N. Margall, P. Coll, A. Stell, and J. R. Johnson. 2000. Escherichia coli serotype O15:K52:H1 as a uropathogenic clone. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:201-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salamon, H., M. R. Segal, A. Ponce de Leon, and P. M. Small. 1998. Accommodating error analysis in comparison and clustering of molecular fingerprints. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 4:159-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swaminathan, B., and T. J. Barrett. 1995. Amplification methods for epidemiologic investigations of infectious diseases. J. Microbiol. Methods 23:129-139. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson, W. C. 1995. Subjective interpretation, laboratory error and the value of forensic DNA evidence: three case studies. Genetica 96:153-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]