Abstract

Background

We report treatment outcomes for a large non-endemic cohort of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) and chemotherapy.

Methods

We identified 177 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed, non-metastatic nasopharyngeal cancer treated with definitive IMRT between 1998 and 2011. Endpoints included local, regional, distant control, and overall survival.

Results

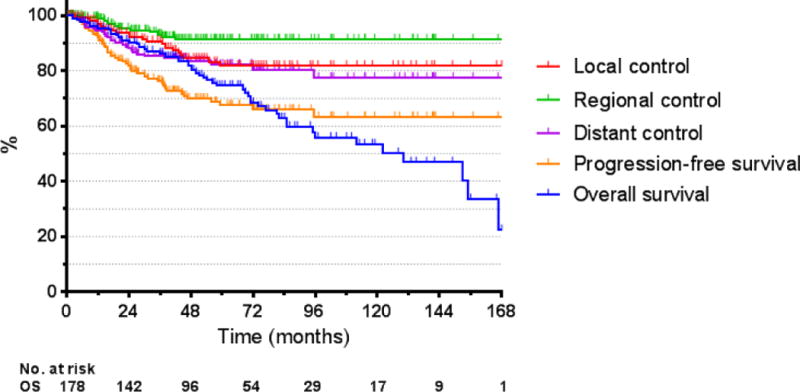

Median follow-up was 52 months. The 3-/5-year actuarial rates of local control, regional control, distant control, and overall survival were 92%/83%, 93%/91%, 86%/83%, and 87%/74%, respectively. The median time to local recurrence was 30 months; the annual hazard of local recurrence did not diminish until the 6th year of follow-up.

Conclusion

s. Overall, we observed excellent rates of disease control and survival consistent with initially reported results from our institution. Attaining locoregional control in patients with extensive primary tumors remains a significant clinical challenge. With mature follow-up we observed that more than half of observed local relapses occurred after 2 years, a pattern distinct from that of carcinomas arising from other head and neck sites. These findings raise the possibility that patients with NPC may benefit from close follow-up during post-treatment years 3–5.

Keywords: clinical outcomes, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, radiotherapy, IMRT

INTRODUCTION

Intensity-modulated radiotherapy has developed into the standard definitive treatment for nasopharyngeal carcinoma over the past 15 years, in both the United States and in Asia, where Epstein-Barr virus-related non-keratinizing carcinomas of the nasopharynx are endemic.(1, 2) Three randomized trials have compared IMRT to conventional radiotherapy in the treatment of NPC.(3–5) Although local control rates with IMRT have improved with the advent and now widespread adoption of IMRT, distant recurrence remains a persistent problem. The addition of chemotherapy has been shown to demonstrate a survival benefit among those with locally advanced NPC in both North American(6) and Asian clinical trials.(7–9)

Numerous studies have reported long-term follow-up for patients with NPC treated with IMRT, but relatively few have reported mature outcomes from non-endemic series.(10–12) In this retrospective analysis, we report treatment outcomes for a large non-endemic cohort of such patients with long-term follow-up.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A waiver of informed consent for retrospective analysis of individual patient data was obtained from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) institutional review board. The MSKCC tumor registry and Radiation Oncology departmental databases were used to identify all patients with a diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with definitive IMRT between 07/1998 and 04/2011. After exclusion of patients with recurrent or metastatic disease at presentation, we identified 177 patients who form the study cohort of the present analysis.

Patient/staging evaluation

A complete medical history, physical examination with fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy, computed tomographic (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging scans of the nasopharynx, skull base, neck were performed as part of the pretreatment evaluation. Chest imaging consisted of either plain film radiograph or CT scan during the early portion of the study period. Pretreatment magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the nasopharynx/skull base were routinely acquired for all patients unless there was a contraindication. Positron emission tomography (PET) scans were initially performed as clinically indicated on the basis of abnormal screening test results or symptoms, but became part of the standard staging workup during the study period. For the purposes of the present study, patients were restaged according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual.

Radiotherapy

The use of IMRT in the treatment of nasopharynx cancer was implemented in July of 1998. During the early portion of the study period 59 patients were treated with a hyperfractionated concomitant boost regimen. Patients who received this fractionation regimen were treated to a total dose of 70 Gy in 6 weeks. An IMRT plan encompassing all areas of gross and presumed microscopic disease was used for the first 20 fractions, followed by 10 days of twice-daily treatment, each day using the initial IMRT plan for the first treatment and a second IMRT plan to boost sites of gross disease for the second treatment.(11) From 2002 to 2007, 25 patients enrolled on an single-institution phase I/II protocol (IRB# 02-077A) were treated using hypofractionated dose-painting IMRT to a total dose of 70 Gy in 30 daily fractions of 2.34 Gy.(13) The remaining patients included in this study were treated with dose-painting IMRT to a total dose of 70 Gy in 33 fractions (PTV70 received 70 Gy in 2.12 Gy/fraction, and PTV59.4 received 1.8Gy/fraction). Fusion of MRI and/or PET with treatment planning CT images was implemented whenever possible to increase accuracy in target delineation.

The approach to target delineation evolved during the study time period. In the initial approach, a ‘PTVg’ was defined by adding a 1-cm margin to the gross tumor volume to include both biologic and technical uncertainties. This margin was applied isotropically except posterior to the primary tumor where a 5-mm margin was used. A second PTV that encompassed both the gross disease and volumes at high risk for microscopic involvement, plus 5-mm margin, was termed ‘PTVm.’

In a later approach used for patients treated with dose-painting IMRT two CTVs were defined as follows: CTV70 = GTV (no margin unless there was uncertainty to extent of gross disease), CTV59.4 = CTV70 + 5 mm margin plus areas at high risk for microscopic involvement. High risk regions for microscopic involvement included the entire nasopharynx, retropharyngeal nodal regions, skull base, clivus, pterygoid fossae, parapharyngeal space, sphenoid sinus, the posterior third of the nasal cavity or maxillary sinuses that includes the pterygopalatine fossae and level I–V lymph node regions. Elective nodal irradiation of the low neck (levels IVB and VB) consisted of an extended IMRT field or a matching conventional anterior-posterior field to 50.4 Gy at 1.8 Gy per fraction. In the extended IMRT field approach, the low neck was included in a lower-risk CTV treated to 54 Gy at 1.64 Gy per fraction at the discretion of the treating physician. A planning target volume (PTV) of 3–5mm was added to each of the CTVs previously mentioned to account for organ motion and daily treatment set-up uncertainties. Margins could be reduced to 1mm in areas where the GTV or CTV was adjacent to critical normal structures such as the brainstem.

Chemotherapy

The vast majority (158; 89%) of patients received concurrent chemotherapy, including 126 (71%) who received both concurrent and adjuvant chemotherapy. Among this group of patients, 91% were treated as per the INT-0099 trial: 2–3 cycles of cisplatin (100mg/m2) administered every 3 weeks during radiotherapy, and up to 3 planned cycles of adjuvant cisplatin (80mg/m2) and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU; 1000mg/m2/day).(6) Patients with significant renal dysfunction, neuropathy (including hearing loss) or other contraindication received carboplatin/5-fluorouracil in lieu of cisplatin (3%). Other alternate concurrent/adjuvant regimens included weekly cisplatin followed by adjuvant carboplatin/5-FU (2%), or cisplatin/bevacizumab (4%; RTOG 0615).(14)

Twenty-four patients (13%) received concurrent but not adjuvant chemotherapy. Eight patients (4%) received neoadjuvant and concurrent chemotherapy, including 4 who received platinum/fluorouracil-based (PF) neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and 4 who received taxane/platinum/fluorouracil (TPF) neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Follow-up

Patients were evaluated weekly during the course of radiotherapy. After completing their treatment, patients were evaluated every 2–3 months for the first 2 years. Past this time point, evaluations were performed every 4–6 months. Follow up visits consisted of physical exams, flexible fiberoptic endoscopy, and neck palpation. Imaging studies were performed to document treatment response, determine whether patients were clinically free from disease, or required further diagnostic biopsy and/or treatment. Three months after treatment, a positron emission tomography scan as well as CT or magnetic resonance imaging scan of the nasopharynx and neck were performed as well. Chest radiographs or other imaging was performed annually to assess for distant metastases.

Endpoints and statistical analysis

Actuarial rates of local control, regional control, locoregional control, distant control, progression-free survival and overall survival were calculated from the start of RT using the Kaplan-Meier method. Progression-free survival was defined as freedom from disease recurrence and death from any cause. Univariate and multivariate analyses using Cox proportional hazard regression models were performed to determine the predictive value of patient, tumor and treatment variables on censored treatment outcomes. The annual hazard of disease relapse was estimated using the life-table method.

RESULTS

Median follow-up among all patients and among surviving patients was 52 and 70 months, respectively. Patient and tumor characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Among 177 patients, 26 patients developed locoregional recurrence, and 27 patients developed distant recurrence during the follow-up period. Among those patients who developed a locoregional recurrence, there were 10 with an isolated local recurrence, 4 with an isolated regional recurrence, 7 with both local and regional recurrences, 3 with local and distant recurrences, and 1 patient with local, regional and distant recurrence.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median | 52 |

| <40 | 36 (20) |

| 40–50 | 47 (27) |

| 51–60 | 47 (27) |

| 61–70 | 30 (17) |

| >70 | 17 (10) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 125 (71) |

| Female | 52 (30) |

| Smoking status* | |

| Never | 92 (52) |

| Former | 54 (31) |

| Current | 31 (18) |

| Smoking pack-years** | |

| <100 cigarettes lifetime | 92 (52) |

| 0–10 | 17 (10) |

| >10 | 60 (34) |

| Unknown | 8 (5) |

| Ethnicity/Race | |

| White† | 89 (51) |

| Black† | 16 (9) |

| Asian | 55 (31) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 14 (8) |

| Unknown | 3 (2) |

| T-category | |

| T1 | 66 (36) |

| T2 | 37 (20) |

| T3 | 48 (26) |

| T4 | 26 (14) |

| N-category | |

| N0 | 48 (26) |

| N1 | 49 (27) |

| N2 | 55 (30) |

| N3a | 9 (5) |

| N3b | 16 (9) |

| Histology | |

| Keratinizing | 11 (6) |

| Non-keratinizing | 125 (69) |

| Basaloid | 2 (1) |

| Unknown | 39 (21) |

‘Never’ defined as less than 100 cigarettes life-time. ‘Former’ defined as smoking cessation for at least 12 months.

Among ‘former’ or ‘current’ smokers.

Non-hispanic/latino ethnicity.

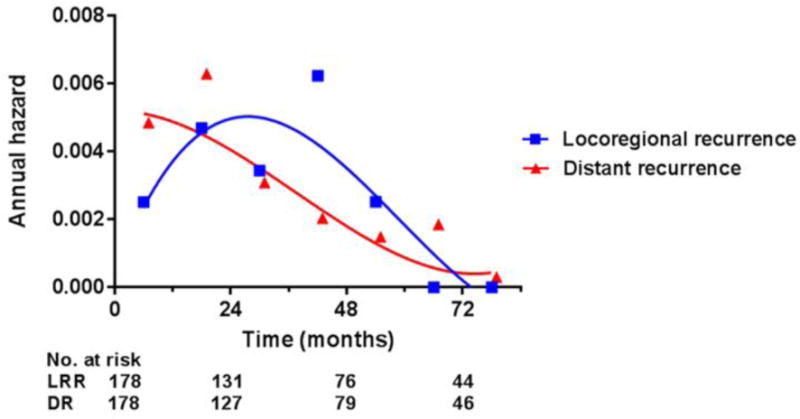

The 3- and 5-year actuarial rates of local control were 92% (95% confidence intervals: 88–96%) and 83% (76–90%), respectively. The median time to local recurrence was 30 months. More than half (13 of 23) of the local relapses observed in our series occurred after 2 years Figure 2 details the annual hazard of local, regional, and distant recurrence by year of follow-up. The 3- and 5-year actuarial rates of regional control were 93% (89–97%) and 91% (87–96%), respectively. The median time to regional recurrence was 19 months. The 3- and 5-year rates of locoregional control were 89% (84–94%) and 80% (72–87%), respectively. The 3- and 5-year rates of distant control were 86% (80–91%) and 83% (76–89%), respectively. The median time to distant recurrence was 17 months.

Figure 2. Annual hazard of locoregional and distant recurrence.

Abbreviations: LRR, locoregional recurrence; DR, distant recurrence.

Treatment outcomes stratified by T-, N-category and overall stage are detailed in Table 2. Patients with T4 disease were at markedly elevated risk of local, regional and distant recurrence compared to those with less advanced primary tumors, as evidenced by 5-year progression-free survival of 42%. When analyzed as an ordinal variable, advanced T-category was associated with a significantly increased of local recurrence, as well as a trend towards increased risk of regional and distant recurrence (Table 3). When patients were dichotomized between T4 and T1–3 disease, the prognostic value of T-category for regional (p=0.02) and distant (p=0.03) recurrence did reach statistical significance.

Table 2.

Treatment outcomes by T, N-category and overall stage.

| # | Percent survival estimated by Kaplan-Meier method (95% confidence intervals) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local control | Regional control | Distant control | Progression-free survival | Overall survival | |||||||

| 3-yr (95%CI) | 5-yr (95%CI) | 3-yr (95%CI) | 5-yr (95%CI) | 3-yr (95%CI) | 5-yr (95%CI) | 3-yr (95%CI) | 5-yr (95%CI) | 3-yr (95%CI) | 5-yr (95%CI) | ||

| All pts | 178 | 92 (88–96) | 83 (76–90) | 93 (89–97) | 91 (87–96) | 86 (80–91) | 83 (76–89) | 77 (70–83) | 68 (60–76) | 87 (81–92) | 74 (67–81) |

| T-category†* | |||||||||||

| T1 | 66 | 98 (95–100) | 88 (78–98) | 95 (89–100) | 93 (86–100) | 92 (85–99) | 89 (81–98) | 89 (81–96) | 76 (64–89) | 94 (88–100) | 85 (74–95) |

| T2 | 37 | 96 (89–100) | 86 (71–100) | 96 (89–100) | 96 (89–100) | 77 (62–92) | 77 (62–92) | 74 (59–90) | 66 (48–83) | 74 (59–88) | 66 (49–83) |

| T3 | 48 | 88 (79–98) | 85 (74–96) | 96 (89–100) | 93 (85–100) | 88 (78–98) | 85 (73–96) | 74 (61–88) | 69 (55–83) | 95 (89–100) | 76 (62–91) |

| T4 | 26 | 72 (50–93) | 55 (28–81) | 75 (54–97) | 75 (54–97) | 75 (55–94) | 65 (41–90) | 49 (26–72) | 42 (19–65) | 70 (50–89) | 55 (33–76) |

| N-category†* | |||||||||||

| N0 | 48 | 85 (73–96) | 64 (46–82) | 94 (86–100) | 94 (86–100) | 92 (84–100) | 87 (74–100) | 80 (67–92) | 63 (45–81) | 84 (73–95) | 81 (70–93) |

| N1 | 49 | 88 (79–98) | 85 (74–96) | 91 (82–99) | 91 (82–99) | 84 (73–95) | 84 (73–95) | 73 (59–86) | 69 (55–83) | 91 (83–99) | 73 (58–88) |

| N2 | 55 | 98 (94–100) | 90 (80–99) | 92 (84–100) | 87 (77–97) | 84 (74–94) | 78 (66–91) | 76 (64–88) | 64 (50–78) | 90 (82–98) | 69 (54–83) |

| N3a | 9 | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 43 (6–80) | 43 (6–80) | 43 (6–80) | 43 (6–80) | 45 (8–82) | 45 (8–82) |

| N3b | 16 | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 87 (70–100) | 87 (70–100) |

| Stage†* | |||||||||||

| I | 19 | 100 (N/A) | 92 (78–100) | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 81 (56–100) | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) |

| II | 40 | 94 (87–100) | 87 (75–99) | 91 (82–100) | 91 (82–100) | 86 (75–98) | 86 (75–98) | 81 (68–93) | 81 (56–100) | 85 (74–96) | 75 (60–90) |

| III | 72 | 92 (86–99) | 86 (76–95) | 96 (90–100) | 91 (84–99) | 86 (77–95) | 81 (71–92) | 76 (65–86) | 73 (58–88) | 94 (77–100) | 75 (63–87) |

| IVA | 21 | 65 (40–91) | 41 (9–73) | 69 (43–95) | 69 (43–95) | 73 (51–96) | 69 (55–83) | 41 (16–67) | 31 (5–57) | 67 (45–89) | 49 (25–73) |

| IVB | 25 | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 100 (N/A) | 82 (65–98) | 82 (65–98) | 82 (65–98) | 82 (65–98) | 74 (55–92) | 74 (55–92) |

Abbreviations: HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence intervals.

Analyzed as an ordinal variable.

American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th edition.

Table 3.

Univariate Cox regression analysis.

| # | Local control | Regional control | Distant control | Progression-free survival | Overall survival | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | ||

| T-category†* | 1.77 (1.2–2.7) | 0.006 | 1.54 (0.9–2.6) | 0.11 | 1.37 (1.0–1.9) | 0.07 | 1.46 (1.1–1.9) | 0.005 | 1.28 (1.0–1.6) | 0.05 | |

| N-category†* | 0.45 (0.3–0.7) | 0.002 | 0.93 (0.6–1.5) | NS | 1.1 (0.79–1.5) | NS | 0.90 (0.7–1.2) | NS | 1.02 (0.8–1.3) | NS | |

| Stage†* | 1.07 (0.7–1.5) | NS | 1.18 (0.7–1.9) | NS | 1.34 (1.0–1.9) | 0.06 | 1.10 (0.9–1.5) | NS | 1.23 (1.0–1.5) | 0.07 | |

| Histology | NS | NS | 0.19 | NS | 0.01 | ||||||

| Non-keratinizing (reference) | 125 | ||||||||||

| Keratinizing | 11 | 2.18 (0.5–9.7) | NS | 2.86 (0.6–13.3) | 0.18 | No events | NS | 1.30 (0.4–4.3) | NS | 2.30 (0.8–6.6) | 0.13 |

| Basaloid | 2 | No events | NS | No events | NS | No events | NS | No events | NS | No events | NS |

| Unknown | 39 | 1.75 (0.7–4.6) | NS | 0.42 (0.1–3.3) | NS | 2.39 (1.1–5.2) | 0.03 | 1.96 (1.1–3.7) | 0.03 | 2.55 (1.4–4.5) | 0.002 |

| Smoking status‡ | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||||||

| Never (reference) | 92 | ||||||||||

| Former | 54 | 0.96 (0.4–2.6) | NS | 2.26 (0.6–8.4) | NS | 0.95 (0.4–2.2) | NS | 1.07 (0.6–2.0) | NS | 1.60 (0.9–2.9) | 0.12 |

| Current | 31 | 1.17 (0.4–3.7) | NS | 2.47 (0.6–11.0) | NS | 0.85 (0.3–2.6) | NS | 1.00 (0.5–2.2) | NS | 1.67 (0.8–3.3) | 0.15 |

| Smoking pack-years | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) | NS | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | 0.17 | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | NS | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | 0.001 | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | 0.001 | |

| Ethnicity | NS | NS | <0.001 | 0.002 | NS | ||||||

| White♯ (reference) | 89 | ||||||||||

| Black♯ | 16 | No events | NS | No events | NS | 2.18 (0.6–8.1) | NS | 0.97 (0.3–3.3) | NS | 1.02 (0.4–2.6) | NS |

| Asian | 55 | 1.30 (0.5–3.1) | NS | 1.08 (0.3–3.8) | NS | 1.79 (0.7–4.4) | NS | 1.50 (0.8–2.8) | NS | 0.79 (0.4–1.4) | NS |

| Hispanic/Latino | 14 | 0.84 (0.1–6.6) | NS | 2.78 (0.6–13.8) | NS | 1.85 (0.4–8.6) | NS | 1.78 (0.6–5.2) | NS | 1.08 (0.3–3.5) | NS |

| Unknown | 3 | No events | NS | No events | NS | 23.6 (6.2–90) | <0.001 | 13.0 (3.8–45) | <0.001 | 3.12 (0.4–23.4) | NS |

| Gender‖ | 1.54 (0.6–4.2) | NS | 1.42 (0.4–5.3) | NS | 1.34 (0.6–3.2) | NS | 1.44 (0.8–2.8) | NS | 1.24 (0.7–2.2) | NS | |

| Age at diagnosis† | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.02 | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | NS | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | NS | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.03 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.03 | |

| Chemotherapy | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||||||

| Concurrent + adjuvant (reference) | 126 | ||||||||||

| Concurrent only | 24 | 1.34 (0.4–4.7) | NS | 0.68 (0.1–5.4) | NS | 1.23 (0.4–3.6) | NS | 1.08 (0.5–2.6) | NS | 1.54 (0.7–3.2) | NS |

| Neoadjuvant + concurrent | 8 | 1.76 (0.2–13.4) | NS | 2.69 (0.3–21.3) | NS | 1.07 (0.1–8.0) | NS | 1.22 (0.3–5.1) | NS | 0.77 (0.1–5.6) | NS |

| None | 19 | 1.39 (0.4–4.8) | NS | 0.71 (0.1–5.6) | NS | 0.30 (0.04–2.3) | NS | 0.67 (0.2–1.9) | NS | 0.64 (0.2–1.8) | NS |

Abbreviations: HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence intervals; NS: not significant (p values displayed if <0.2)

Analyzed as an ordinal variable.

American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th edition.

’Never’ defined as less than 100 cigarettes life-time. ‘Former’ defined as smoking cessation for at least 12 months.

Hazard associated with male gender.

Non-hispanic/latino ethnicity.

The hazard of local or regional relapse among patients with keratinizing disease was more than 2-fold greater than that of patients with non-keratinizing disease (Table 3), but this was not statistically significant given that only 11 patients had tumors of keratinizing histology. Of note, there were 39 patients whose histology could not be accurately determined by retrospective review of the chart, as the presence or absence of keratinization was not explicitly mentioned in the pathology report. These patients were at elevated risk of distant recurrence compared to those with non-keratinizing histology (HR 2.39, p=0.03). Patients with keratinizing carcinoma were more likely to be current smokers (55% vs 16%, p=0.002) and of non-Asian ethnicity (100% vs 63%, p=0.01) than those with keratinizing disease. This did not hold true for those with unknown keratinization status (13% vs 16% and 80% vs 63%, respectively).

DISCUSSION

The 3-year treatment outcomes we report in the present study are consistent with prior reports from our institution.(11, 13) Among 177 patients, we observed 3-year actuarial local and regional control rates of 92% and 93%, respectively, almost identical to the 3-year rates previously reported by Wolden et al. for the first 74 patients in our series. With further follow-up and more than twice the number of patients, we have updated those results to report 5-year actuarial local and regional control rates of 83% and 91%, respectively. More than half (13 of 23) of the local relapses observed in our series occurred after 2 years, a pattern distinct from that of carcinomas arising from other head and neck sites. In a previously published series of 442 oropharyngeal cancer patients treated with IMRT at our institution, for example, no local recurrences were seen after 2 years.(15) In contrast, patients with NPC included in our series had an appreciable annual hazard of local recurrence until the 6th year of follow-up (Table 2).

Although it is arguably underappreciated, this predilection for late locoregional recurrence can be seen among published data from large randomized prospective trials, including the recent update of the Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy in Nasopharynx Carcinoma (MAC-NPC).(16) Among 634 patients treated with concomitant and adjuvant chemotherapy, 40 of 79 (51%) observed locoregional recurrences occurred after more than 2 years of follow-up. Similarly, among 912 patients treated with concomitant chemotherapy alone, 78 of 169 (46%) locoregional recurrences were observed after 2 years. A smaller proportion of LRR occurred after 2 years (30%) among those who were randomized to no chemotherapy, but this was due to a higher rate of early recurrence, rather than a reduction in the absolute rate of locoregional recurrence after 2 years.(16) Given that the extent of disease at the time of salvage therapy for locoregional recurrence has been shown to be prognostic of outcome,(17–19) patients with NPC may benefit from continued close follow-up during post-treatment years 3–5.

Although treatment outcomes in the overall cohort were excellent, the 26 patients in our series with T4 disease patients were at significantly elevated risk of locoregional and distant relapse, as evidenced by 5-year local, regional, and distant control rates of 55% (95% CI: 28–81%), 75% (54–97%), and 65% (41–90%), respectively. Attaining locoregional control in patients with extensive primary tumors remains a significant clinical challenge, despite the improvements in dosimetry afforded by IMRT. The poor prognosis associated with T4 disease in our series may be related to the disproportionately unfavorable biology seen in locally advanced tumors, which have been shown to display a heavier mutational burden than early stage tumors.(20) We observed an inverse correlation between T4 primary disease and non-keratinizing histology in our series, but this relationship did not reach statistical significance (p=0.09).

In contrast to primary tumor stage, advanced nodal stage predicted for significantly improved local control. This appeared to be driven, in part, by an elevated risk of local relapse among patients with T4N0 disease; among 8 such patients, 5 developed local recurrence. Nodal stage was not predictive of regional or distant relapse when analyzed as an ordinal variable. Excellent outcomes were observed among the 16 patients with supraclavicular (N3b) nodal disease, none of whom developed disease relapse. In contrast, bulky nodal disease (>6cm; N3a) was associated with a high rate of distant recurrence (44% 3-yr distant control), albeit in a small sample size of 9 patients.

The prognostic value of keratinization in NPC is previously reported and widely recognized.(21) Non-keratinizing histology, which has a known association with EBV-positivity and improved survival outcomes, constitutes a smaller proportion of cases in the United States compared to endemic areas, where it is the predominant histologic subtype.(22) Our cohort contained relatively few patients with keratinizing histology (8% among those with known histology) compared to older non-endemic series. Twenty-four percent of patients in the Intergroup 0099 cohort, for example, had keratinizing disease.(6) The 8% rate we observed in the present study is, however, consistent with more contemporary non-endemic NPC series.(10, 12) RTOG 0225, which accrued patients from 17 North American centers, reported an 8.8% rate of keratinizing histology. Consistent with this trend, a recent report from the University of Pittsburgh identified a decrease in keratinizing histology from 35% to 14% over the past several decades.(23) While we did observe a relatively low rate of keratinization, it must be mentioned that we could not exclude the possibility of additional patients with keratinizing disease, as the presence or absence of keratinization could not be explicitly determined in 21% of our cohort. This subset of patients had inferior local and distant control rates compared to those with non-keratinizing disease, but did not have the patient characteristics typically associated with keratinizing disease such as an increased proportion of non-Asian ethnicity and significant smoking history.

In our multivariate analysis of factors associated with patient outcomes (Table 4), the only factors significantly predictive of overall survival were T-category, non-keratinizing histology, and age at diagnosis. As expected, advanced primary tumor stage was additionally associated with an increased risk of local and distant relapse. Age at diagnosis was also significantly associated with disease control; each increasing year was associated with a 3.6% increase in the hazard of local relapse (p=0.04) and a 2.4% increase in the hazard of distant relapse (p=0.02). Despite being predictive of better overall survival, non-keratinizing histology was not significantly associated with locoregional or distant control. Although we found ethnicity to be predictive of distant control and progression-free survival in univariate analysis, this was driven by a small subset of 3 patients with unknown ethnicity who developed distant recurrence. We did not observe any significant relationship between Asian ethnicity and disease control or survival.

Table 4.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis.

| Local control | Regional control | Distant control | Progression-free survival | Overall survival | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | |

| T-category†* | 1.82 (1.2–2.8) | 0.006 | 1.58 (0.9–2.7) | 0.10 | 1.44 (1.0–2.1) | 0.05 | 1.52 (1.2–2.0) | 0.003 | 1.33 (1.0–1.8) | 0.04 |

| N-category†* | 0.50 (0.3–0.8) | 0.01 | 0.99 (0.6–1.6) | NS | 1.10 (0.8–1.5) | NS | 0.93 (0.7–1.2) | NS | 1.12 (0.9–1.4) | NS |

| Non-keratinizing histology‡ | 0.72 (0.3–1.9) | NS | 1.25 (0.3–4.7) | NS | 0.64 (0.3–1.5) | NS | 0.67 (0.4–1.2) | 0.11 | 0.52 (0.3–0.9) | 0.03 |

| Smoking pack-years† | 0.995 (0.97–1.02) | NS | 1.010 (0.99–1.04) | NS | 0.985 (0.32–1.7) | NS | 0.989 (0.97–1.01) | NS | 1.008 (1.00–1.02) | 0.19 |

| Age at diagnosis† | 1.036 (1.00–1.07) | 0.04 | 1.024 (0.98–1.07) | NS | 1.023 (1.00–1.05) | 0.08 | 1.024 (1.00–1.04) | 0.02 | 1.034 (1.01–1.06) | 0.002 |

Abbreviations: HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence intervals; NS: not significant (p values displayed if <0.2)

Analyzed as an ordinal variable.

American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th edition.

Non-keratinizing vs any other histology (including unknown).

Multiple clinical trials and meta-analyses have clearly demonstrated the role of concurrent chemotherapy as a cornerstone of the treatment of locally-advanced NPC.(6, 7, 9, 24–26) Despite multiple randomized studies attempting to improve on outcomes achieved with the Intergroup 00–99 regimen, concurrent chemoradiotherapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with platinum-based regimens remains the standard of care for locoregionally advanced NPC. Among 158 patients with stage II-IVB disease included in our series, all but 1% received concurrent chemotherapy, including 79% who received both concurrent and adjuvant chemotherapy. Only 5% of patients received neoadjuvant and concurrent chemotherapy. Given the relative uniformity with which chemotherapy was delivered, it was unsurprising that we did not see any significant relationship between treatment outcomes and the sequence of chemotherapy delivery in our series.

Our study has several significant limitations, including its retrospective and non-randomized nature. Our data do not address late toxicities, the incidences of which are critical to defining the therapeutic window of chemoradiotherapy for NPC. We also had relatively few patients with data regarding the presence or absence of EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER) staining or circulating EBV DNA, preventing us from assessing the prevalence of EBV-related disease in this non-endemic cohort.

In conclusion, we report long-term treatment outcomes for a large non-endemic cohort of patients uniformly treated with IMRT and chemotherapy. Overall, treatment outcomes were excellent and consistent with initially reported results from our institution. With further followup, we observed late locoregional and distant recurrences inherent to the natural history of NPC, highlighting the importance of long-term multidisciplinary follow-up. Attaining locoregional control in non-endemic patients with extensive primary tumors remains a significant clinical challenge, despite the improvements in dosimetry afforded by IMRT.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier treatment outcomes.

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival.

We report long-term patterns of relapse after definitive IMRT for non-endemic NPC.

177 patients were included, including 158 who received concurrent chemotherapy.

Overall, outcomes were excellent and consistent with reported short-term results.

More than half of local relapses occurred after 2 years.

Our results highlight critical importance of long-term multidisciplinary follow-up.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Notification

The authors (Jeremy Setton, MD, James Han, MD, Danita Kannarunimit, MD, Yen-Ruh Wuu, BS, Stephen A Rosenberg, MD, Carl DeSelm, MD, Suzanne Wolden, MD, Jillian Tsai, MD, Sean McBride, MD, Nadeem Riaz, MD, Nancy Lee, MD) have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Lee N, Harris J, Garden AS, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: radiation therapy oncology group phase II trial 0225. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(22):3684–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang TJ, Riaz N, Cheng SK, Lu JJ, Lee NY. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a review. Journal of Radiation Oncology. 2012;1(2):129–146. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pow EH, Kwong DL, McMillan AS, et al. Xerostomia and quality of life after intensity-modulated radiotherapy vs conventional radiotherapy for early-stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma: initial report on a randomized controlled clinical trial. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics. 2006;66(4):981–991. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kam MK, Leung S-F, Zee B, et al. Prospective randomized study of intensity-modulated radiotherapy on salivary gland function in early-stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(31):4873–4879. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng G, Wang T, Yang KY, et al. A prospective, randomized study comparing outcomes and toxicities of intensity-modulated radiotherapy vs conventional two-dimensional radiotherapy for the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 2012;104(3):286–93. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Sarraf M, LeBlanc M, Giri P, et al. Chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy in patients with advanced nasopharyngeal cancer: phase III randomized Intergroup study 0099. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1998;16(4):1310–1317. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin JC, Jan JS, Hsu CY, Liang WM, Jiang RS, Wang WY. Phase III study of concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone for advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: positive effect on overall and progression-free survival. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(4):631–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan AT, Leung SF, Ngan RK, et al. Overall survival after concurrent cisplatin-radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(7):536–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwong DL, Sham JS, Au GK, et al. Concurrent and adjuvant chemotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a factorial study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(13):2643–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee N, Xia P, Quivey JM, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy in the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an update of the UCSF experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53(1):12–22. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02724-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolden SL, Chen WC, Pfister DG, Kraus DH, Berry SL, Zelefsky MJ. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) for nasopharynx cancer: update of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering experience. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics. 2006;64(1):57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takiar V, Ma D, Garden AS, et al. Disease control and toxicity outcomes for T4 carcinoma of the nasopharynx treated with intensity modulated radiotherapy. Head Neck. 2015 doi: 10.1002/hed.24128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakst RL, Lee N, Pfister DG, et al. Hypofractionated dose-painting intensity modulated radiation therapy with chemotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a prospective trial. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics. 2011;80(1):148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee NY, Zhang Q, Pfister DG, et al. Addition of bevacizumab to standard chemoradiation for locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma (RTOG 0615): a phase 2 multi-institutional trial. The lancet oncology. 2012;13(2):172–180. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70303-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Setton J, Caria N, Romanyshyn J, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy in the treatment of oropharyngeal cancer: an update of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(1):291–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blanchard P, Lee A, Marguet S, et al. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an update of the MAC-NPC meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(6):645–55. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leung T-W, Tung SY, Sze W-K, et al. Salvage radiation therapy for locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics. 2000;48(5):1331–1338. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00776-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang JT-C, See L-C, Liao C-T, et al. Locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2000;54(2):135–142. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(99)00177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riaz N, Hong JC, Sherman EJ, et al. A nomogram to predict loco-regional control after re-irradiation for head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2014;111(3):382–7. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin DC, Meng X, Hazawa M, et al. The genomic landscape of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46(8):866–71. doi: 10.1038/ng.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersson F. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a review. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2015;32(1):54–73. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2015.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheung F, Chan O, Ng WT, Chan L, Lee A, Pang SW. The prognostic value of histological typing in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2012;48(5):429–33. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dogan S, Hedberg ML, Ferris RL, Rath TJ, Assaad AM, Chiosea SI. Human papillomavirus and Epstein-Barr virus in nasopharyngeal carcinoma in a low-incidence population. Head Neck. 2014;36(4):511–6. doi: 10.1002/hed.23318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baujat B, Audry H, Bourhis J, et al. Chemotherapy in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an individual patient data meta-analysis of eight randomized trials and 1753 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64(1):47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan AT, Teo PM, Ngan RK, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy-radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: progression-free survival analysis of a phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(8):2038–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeo W, Leung TW, Chan AT, et al. A phase II study of combination paclitaxel and carboplatin in advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(13):2027–31. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00280-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]