Abstract

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that primarily affects the lungs. Our previous work indicates that activation of p38 plays a pivotal role in sarcoidosis inflammatory response. Therefore, we investigated the upstream kinase responsible for activation of p38 in sarcoidosis alveolar macrophages (AMs) and peripheral mononuclear cells (PBMCs). We identified that sustained p38 phosphorylation in sarcoidosis AMs and PBMCs is associated with active MKK4 but not with MKK3/6. Additionally, we found that sarcoidosis AMs exhibit a higher expression of IRAK1, IRAK-M and Rip2. Surprisingly, ex vivo treatment of sarcoidosis AMs or PBMCs with IRAK1/4 inhibitor led to a significant increase in IL-1β mRNA expression both spontaneously and in response to TLR2 ligand. However, a combination of Rip2 and IRAK-1/4 inhibitors significantly decreased both IL-1β and IL-6 production in sarcoidosis PBMCs and moderately in AMs. Importantly, a combination of Rip2 and IRAK-1/4 inhibitors led to decreased IFN-γ and IL-6, and decreased percentage of activated CD4+CD25+ cells in PBMCs. These data suggest that in sarcoidosis both pathways, namely IRAK and Rip2 are deregulated. Targeted modulation of Rip2 and IRAK pathways may prove to be a novel treatment for sarcoidosis.

Keywords: Sarcoidosis, p38, IRAK1/4, Rip2, MAPK, Alveolar macrophages, PBMC

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease with a high incidence of pulmonary involvement leading to chronic respiratory failure (1, 2). The immunopathogenesis of sarcoidosis is not well understood. Evidence suggests that exposure to unknown antigen(s) or environmental factors may lead to activation of macrophages as well as T cells, implying the possibility of more than a single antigen (3, 4).

Macrophages and circulating monocytes, as integral part of the innate immunity, can recognize pathogens or products of cell damage through surface expressed leucine rich repeated domains of the pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) or intracellular pattern recognition receptors such as NOD-like receptors (NLRs) (5, 6). The activation of TLRs and NLRs results in modulating several adapter proteins such as Interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase (IRAK) and receptor interacting protein 2 (Rip2, also known as RICK). In humans IRAKs have four family members namely IRAK1, IRAK2, IRAK4 and IRAKM. The expression of IRAK-M is restricted to macrophages and monocytes, whereas IRAK1, 2 and 4 are ubiquitously expressed (7, 8). The IRAK family activates several signaling pathways that include NF-κB, MAPKs and Interferon regulatory factors (IRFs). The overexpression of kinase deficient IRAK1 can still induce NF-κB suggesting that NF-κB signaling is independent of this IRAK1 kinase activity (9). Cytokine production in IRAK1 knockout mice is diminished in response to TLR activation (10). In comparison, IRAK4 knockout mice do not respond to TLR activation (11) emphasizing the role that IRAK4 plays in TLR signaling. Although IRAK family members are well studied in human and mouse cells their role in sarcoidosis has not been determined.

Rip2 is one of the seven members of the Rip kinase family and has been shown to activate the NF-κB, MAPKs (p38, ERK and JNK) signaling pathways (12–15). Rip2 associates with two novel NLRs, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain proteins 1 and 2 (NOD1, NOD2) and has been implicated in inflammatory diseases such as Crohn’s disease and arthritis (16). Rip2 has been found to be involved in p38 MAPK activation (12). Furthermore, T-cell proliferation and cytokine production in response to TLR ligands are severely effected in Rip2 knockout mice (17, 18). Activation of Rip2 might have a role in sarcoidosis and drugs targeting Rip2 inhibition may prove to be a novel therapy for this disease.

Both alveolar macrophages (AMs) and PBMCs isolated from sarcoidosis patients have been known to produce greater amounts of Th1 cytokines under ex vivo conditions at baseline or in response to TLRs and NLRs ligands (19–22). The p38 MAPK activation is pivotal for the production of many cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β and it plays a role in Th1 activation (23–25). Previously, we have shown that bronchoalveolar (BAL) cells or AMs from sarcoidosis subjects exhibit sustained p38 activation (20). This was mechanistically linked to a lack of negative feedback regulation through the dual specific phosphatase MKP-1 (20). In the current study, we investigated the role of the upstream kinases IRAK1 and Rip2 in p38 activation in sarcoidosis. In an ex vivo model of AMs and PBMCs, we show that AMs and PBMCs of patients with sarcoidosis exhibit higher expression for IRAK1 and Rip2. Furthermore, we found that increased p38 activation in sarcoidosis is associated with MKK4 activation. Finally, we assessed the effect of IRAK1/4 and Rip2 inhibitors on IL-1β and IL-6 production, and the activation of p38 in sarcoidosis AMs and PBMCs. Application of IRAK1/4 inhibitor or Rip2 inhibitors alone did not inhibit the IL-1β and IL-6 production, whereas a combination of IRAK1/4 and Rip2 inhibitors significantly reduced the synthesis of these cytokines and the phosphorylation of p38. Surprisingly, dual inhibition of IRAK1/4 and Rip2 modulated activated T-cells, IL-6 and Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) production in sarcoidosis PBMCs.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO) unless specified otherwise. All ligands, LPS, Pam3CysSK4 (PAM), were purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). IRAK1/4 inhibitor was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Gefitinib (Rip2 inhibitor) was purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). Antibodies against IRAK1, IRAKM and Rip2 and the antibodies against anti- phospho MKK4, MKK3/6, and β-actin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Antibodies against total p38 and phospho p38 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-mouse IgG, anti-goat IgG, and anti-Rabbit IgG antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). The anti-human antibodies used for flow cytometry were pp38-FITC, CD14-PE, CD4-FITC, CD25-PE and purified CD3 were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). The antibodies used for immunostaining CD14 alexa 488 and pp38 alexa 594 were purchased from Molecular Probes (Grand Island, NY).

Study Design

The Committee for Investigations Involving Human Subjects at Wayne State University approved the protocol for obtaining alveolar macrophages by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and blood by phlebotomy from control subjects and patients with sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis diagnosis was based on the ATS/ERS/WASOG statement (26). The criteria for enrollment in the diseased group were: (i) a compatible clinical/radiographic picture consistent with sarcoidosis, (ii) histologic demonstration of non-caseating granulomas on the tissue biopsy, and (iii) exclusion of other diseases capable of producing a similar histologic or clinical picture, such as fungus, mycobacteria. Subjects excluded were: (i) smokers, (ii) receiving immune suppressive medication (defined as corticosteroid alone and/or in combination with immune modulatory medications), (iii) had positive microbial culture in routine laboratory examinations or viral infection; or (iv) had known hepatitis or HIV infections or any immune suppressive condition. The criteria for enrollment in the control group were: (i) absence of any chronic respiratory diseases (ii) lifetime nonsmoker, (iii) absence of HIV or hepatitis infection, and (iv) negative microbial culture. A total of 60 patients with sarcoidosis and 40 controls participated in this study. The medical records of all patients were reviewed, and data regarding demographics, radiography stages, pulmonary function tests, and organ involvements were recorded.

BAL and the preparation of cell suspensions

BAL was collected during bronchoscopy after administration of local anesthesia and before tissue biopsies. Briefly, a total of 150 to 200 mL of sterile saline solution was injected via fiberoptic bronchoscopy; the BAL fluid was retrieved, measured, and centrifuged. Cells recovered from the BAL fluid were filtered through a sterile gauze pad and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in endotoxin-free RPMI 1640 medium (HyClone) supplemented with L-glutamine (Life technologies), penicillin/streptomycin (Life technologies), and 1% fetal calf serum (HyClone), and then counted. BAL cells were cultured on adherent plates for 1 h at 37°C in air containing 5% CO2. Non-adherent cells were removed by aspiration adherent cells were washed three times and used as AMs. Viability of these populations was routinely about 97% and by morphologic criteria the adherent cells were in excess of 98% AMs.

Isolation of PBMCs

PBMCs were isolated from heparinized blood using Ficoll-Histopaque (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) density gradient separation followed by washing twice with PBS. Cell suspension was made in endotoxin-free RPMI 1640 medium (HyClone) supplemented with L-glutamine (Life technologies), penicillin/streptomycin (Life technologies), and 10% fetal calf serum (HyClone). Cells were cultured in 12-well plates for different time periods.

Cell viability

Cell viability was measured using the MTT (3(4,5) dimethyl thiazol-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) assay as described previously (27). Cells equivalent to 1 × 105 ml−1 were seeded in 96-well cell culture plates treated in presence and absence of inhibitor/ligands based on experimental design. Absorbance was measured at 550 nm. Relative cell viability was calculated according to the formula: cell viability = absorbance experimental/absorbance control × 100.

Enzyme- Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and IFN-γ in the conditioned medium were measured by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ELISA DuoKits; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Flow cytometry and cell surface immunostaining

PBMCs from controls subjects or subjects with sarcoidosis were isolated, cultured and after appropriate treatment were stained for the cell surface markers using fluorescent labelled antibodies for CD4, CD25, and CD14. After cell-surface staining with CD14, cells were permeabilized and stained concomitantly with phospho p38. Flow cytometry was performed on a BD LSR II SORP and data analysis was performed using FlowJo software (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, OR). Samples were gated on cells using FSC/SSC and doublet discrimination was performed to identify singlets using SSC-W vs. SSC-A. The flowcytometry work was done at Microscopy, Imaging and Cytometry Resources (MICR) Core at The Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University.

Immunofluorescent staining

Intracellular expression of pp38 in sarcoidosis AMs or PBMCs was visualized by immunofluorescence staining. AMs (1 × 105) or PBMCs (2 × 105) were allowed to adhere on chamber slides for overnight. The cells were washed briefly with PBST and fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde. Cells were washed and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and immunostained with anti-human CD14 alexa 488 and pp38 alexa 594 overnight at 4°C. The next day cells were washed three times with PBS for 5 min, the slide was mounted with a drop of ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen). The slide was examined using an Axiovert 40 CFL fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.).

Protein extraction and immunoblotting

Cells were harvested after the appropriate treatment and washed twice with PBS. Total cellular proteins were extracted by addition of RIPA buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail and antiphosphatase I and II (Sigma Chemicals). Protein concentration was measured with the BCA assay (Thermo Scientific, CA). Equal amounts of proteins (10–25 μg) were mixed 1/1 (v/v) with 2x sample buffer (20% glycerol, 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10% 2-βME, 0.05% bromophenol blue, and 1.25 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8), and fractionated on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad) for 60 minutes at 18 V using a SemiDry Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad). The polyvinylidene difluoride membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 hour, washed, and incubated with primary Abs (1/1000) overnight at 4°C. The blots were washed with TBST and then incubated for 1 h with the horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary anti-IgG Ab using a dilution of 1/10,000 in 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST. Membranes were washed four times in TBST. Immuno-reactive bands were visualized using a chemiluminescent reagent (Amersham GE, PA). Images were captured on Hyblot CL film (Denville; Scientific, Inc; Metuchen, NJ) using JPI automatic X-ray film processor model JP-33. Optical density analysis of signals was performed using Image J software.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase/Real Time-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Life technologies) and reverse transcribed using the ABI Reverse Transcription System (Life technologies). The primers (targeting IL-1β and a reference gene, β-actin) were used to amplify the corresponding cDNA by using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Life technologies). Quantitative analysis of mRNA expression was performed using the ABI instrument (Life Technologies). PCR amplification was performed in a total volume of 20 μL containing 2 μL of each cDNA preparation and 20 pg primers (Invitrogen). The PCR amplification protocol was performed as described previously (27). Relative mRNA levels were calculated after normalizing to β-actin. Data were analyzed using the unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test and the results were expressed as relative fold of change. The following primers were used in the PCR reactions: β-actin: forward: 5′-GATTACTGCTCTGGCTCCTAGC-3′, and reverse: 5′-GACTCATCGTACTCCTGCTTGC-3′; IL-1β, forward: 5′-ACAACAATGACTTGACCGCA-3′, and IL-1β reverse: 5′-GGAATGGTTAATACTGGTGG-3′, RIP2: forward: 5′-GCTCGACAGTGAAAGAAAGGA-3′ and reverse: 5′-AGGCTCATTGCAAATTCCCAAAA-3′.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). One-way analysis of variance test and post hoc repeated measure comparisons (least significant difference) were performed to identify differences between groups. ELISA results were expressed as mean ± SEM. For all analyses, two-tailed p values of less than 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

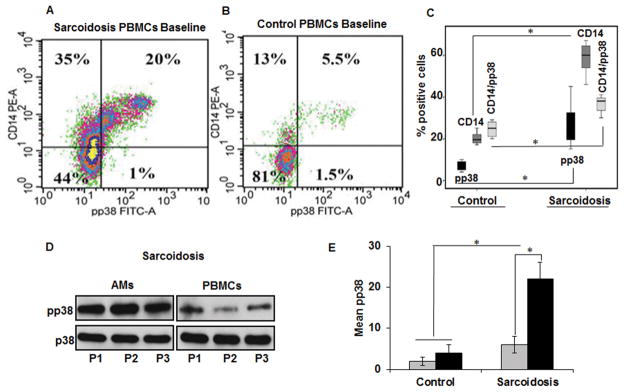

Concordance in p38 activation between circulating CD14+ cells and AMs in sarcoidosis

Previously, we have shown that sarcoidosis AMs and BAL exhibit sustained p38 activation at baseline and in response to stimulation with TLR4 ligands (20). To test the hypothesis that PBMCs of sarcoidosis patients exhibit similar inflammatory phenotypes, we simultaneously assessed p38 activation in PBMCs and AMs in patients with sarcoidosis. All patients were ambulatory outpatients and most patients had radiologic stage 2 sarcoidosis (Table 1). Diagnosis of sarcoidosis was established based on ATS criteria and all samples were examined for microbiology including Mycobacteria species. CD14 is a general marker for macrophages, monocytes and dendritic cells (28). Previously, it has been shown that CD14+ monocytes resemble tissue macrophages and are potent antigen presenting cells and they may play a role in sarcoidosis pathology (29). PBMCs from sarcoidosis and controls were concomitantly stained for CD14 and the active form of p38 (pp38) and analyzed via flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 1A and B, the percentage of CD14+ cells in sarcoidosis was higher (55%) in a representative sample than in healthy control PBMCs, which show about 18% CD14+ monocytes. Similarly, double positive CD14+ cells and phospho p38 (20%) were significantly higher as compared to healthy controls (5%). When the percentage of phospho p38 was normalized to the percentage of total CD14, sarcoidosis PBMCs exhibited about 36% double positive cells, while healthy control PBMCs showed about 27%. Figure1C shows the box blot of cumulative values of 8 patients and 8 controls. These data indicate that PBMCs of patients with sarcoidosis exhibit significantly higher CD14 and phospho p38 positive cells. Furthermore, we analyzed the baseline activation of p38 in PBMCs and AMs from the same patients. Figure 1D shows the Western blots detecting pp38 in both sarcoidosis PBMCs and AMs. We detected higher p38 activation in AMs as compared to PBMCs. Similar results were obtained, when we performed immunohistochemistry in AMs and PBMCs of sarcoidosis patients. Supplementary Figure 1 shows representative immunofluorescence staining using anti CD14 antibody and antibody against phosphorylated form of p38 in AMs (A) and PBMCs (B). Figure 1E summarizes the results of Western blots of phospho p38 both in PBMCs and AMs from 10 controls and 12 sarcoidosis subjects. These results indicate that there is a concordance between sarcoidosis PBMCs and AMs in terms of active p38, but sarcoidosis AMs exhibited higher (2–3 folds) p38 activation as compared to PBMCs. These results are in line with prior studies that CD14 expression is higher in sarcoidosis AMs and PBMCs (20, 30).

Table 1.

Subject Demographics

| Characteristic | Patients | Control Subjects |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 27.7±11.4 | 28±8.4 |

| BMI | 29±10.4 | 28±3.6 |

| Gender, N (%) | ||

| Female | 27 (77) | 15(78) |

| Male | 8 (23) | 4(21) |

| Race, N (%) | ||

| African American | 33 (94) | 15 (78) |

| Caucasian | 2 (6) | 4 (21) |

| CXR stage, N (%) | ||

| 0 | 0 (0) | NA |

| 1 | 4 (11) | NA |

| 2 | 11 (31) | NA |

| 3 | 16(45) | NA |

| Organ Involvements, N (%) | ||

| Neuro-ophtalmologic | 4(28) | NA |

| Lung | 33 (94) | NA |

| Skin | 15 (45) | NA |

| Multiorgan | 26 (52) | NA |

| PPD | Negative | NA |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI=body mass index, CXR=chest X-ray, NA=not applicable, PPD=purified protein derivative

Figure 1. Increased p38 activation in sarcoidosis PBMCs and AMs as compared to healthy controls.

PBMCs from patients (A) and healthy controls (B) were fixed, permeabilized and stained with monoclonal antibodies for CD14 and phospho p38 and analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) Percentage of CD14, pp38 and CD14/pp38 positive cells in PBMCs of 8 controls and 8 sarcoidosis patients presented as box plot. (D) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated p38 and total p38 from sarcoid AMs and PBMCs. Whole cell extracts were prepared from AMs or PBMCs and subjected to SDS-gel electrophoresis. Western blot analysis was performed using antibodies against the phosphop38 and total p38. Representative blot is shown for three different patients (P1–P3). (E) Densitometric values expressed as fold increase of the ratio of phosphorylated p38/total p38 (mean± SEM) from 12 patients and 10 healthy controls. Grey bars represent PBMCs and black bars represent AMs. * p-value < 0.05.

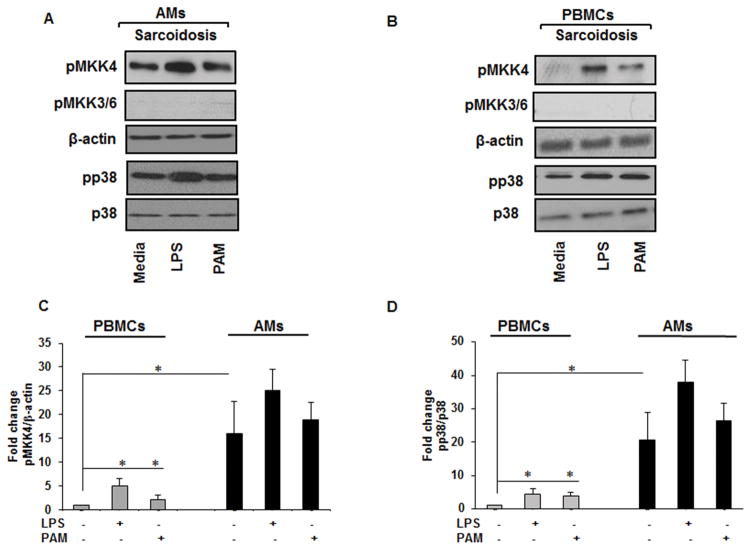

Sustained activation of p38 in sarcoidosis is associated with activated MKK4 but not with MKK3/6

The identification of the predominant kinase(s) with major contribution in p38 activation and determining the level of dysregulation of upstream kinase(s) in sarcoidosis is critical. To model the inflammatory pathway in sarcoidosis, we challenged cells with TLR2 and TLR4 ligands. The rational for such activation was that previously, it has been shown that aberrant TLR2 and TLR4 signaling may play role in sarcoidosis pathology (31, 32). Several upstream kinases including apoptosis signal-regulating kinase-1(ASK1), MKK3/6 and MKK4 can activate p38 (33, 34). We set up the experiments to identify upstream kinase(s), which plays a major role in the p38 activation in sarcoidosis. To identify the potential role of these kinases, we isolated AMs or PBMCs of sarcoidosis patients and assessed the phosphorylation of MKK4 and MKK3/6 as well as ASK1. BALs were cultured on adherent plates and allowed to attach for 1h. They then were challenged with LPS (1 ng/mL) or Pam3CysSK4 (PAM, 100 ng/mL) for 30 min or left untreated in media. Immunoblotting was performed using phospho-specific antibodies against the active forms of p38, MKK3/6 and MKK4. As shown in Figure 2A, AMs of patients with sarcoidosis exhibited higher phospho p38 at the baseline and in response to challenge with TLR2 or TLR4 agonists. We observed similar results with isolated PBMCs of sarcoidosis patients (Fig. 2B). Neither sarcoidosis AMs nor PBMCs showed phosphorylation of MKK3/6 (Fig. 2A&B) nor ASK1 (data not shown) Instead, we detected an increase of activated MKK4 at baseline and in response to PAM or LPS in sarcoidosis AMs and PBMCs (Fig. 2B). Figures 2C and 2D represent of densitometric values (mean±SEM) of phosphorylated form of MKK4 and p38 from 12 different subjects normalized either to β-actin or total p38. These data suggest that AMs exhibited significantly higher pMKK4 as well as phospho p38 expression as compare to PBMCs.

Figure 2. Increased p38 activity in sarcoidosis is associated with MKK4.

AMs and PBMCs from patients were activated with TLR2 (PAM, 100 ng/mL) and TLR4 (LPS, 1 ng/mL) ligands for 30 min. Whole cell extracts of AMs and PBMCs were prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using specific phospho-antibodies for MKK4, MKK3/6, p38. Equal loading was confirmed using antibodies against β-actin or total p38. (A) Sarcoid AMs and (B) PBMCs showed the presence of active (phosphorylated) form of MKK4 at Ser 257/Thr 261 and pp38 both at baseline and in response to LPS and PAM. Representative blots for AMs and PBMCs are shown from one patient out of a total of 12 patients. (C) Densitometric values (mean± SEM) expressed as ratio of phosphorylated MKK4/β-actin from 12 patients. (D) Densitometry values (mean± SEM) expressed as ratio of phosphorylated p38/total p38 from 12 patients. *p-value < 0.05.

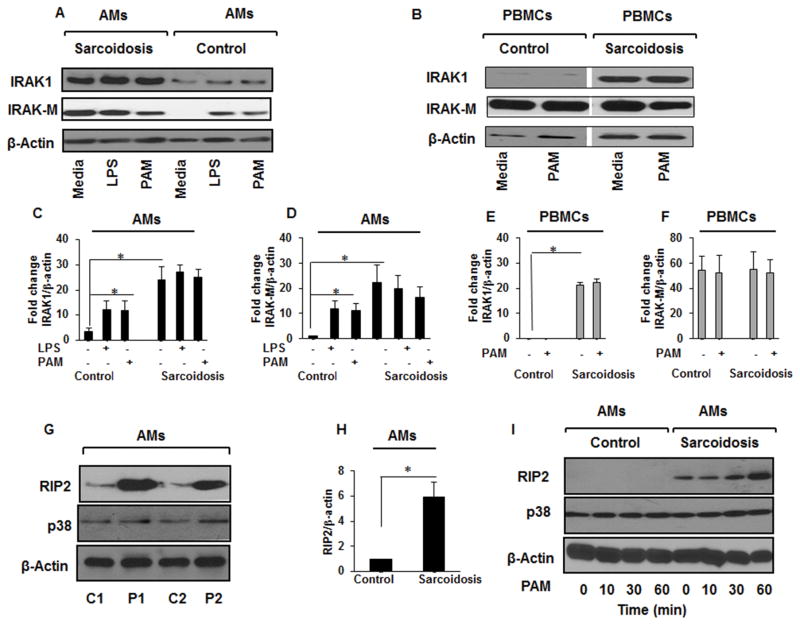

Active p38 is associated with increased IRAK1 and Rip2 proteins in sarcoidosis AMs and PBMCs

Both IRAK1 and Rip2 kinases play an important role in p38 activation (35). IRAK1 interacts with MyD88 and is upstream of a kinase cascade whose activation subsequently activates MAPKs including p38 and NF-κ B leading to the production of inflammatory mediators (36). Although, IRAK1 is well studied in mouse models, its role in human diseases, especially in sarcoidosis is unclear. To determine expression level of IRAK1 in human cells and its role in inflammatory signaling in sarcoidosis, we used two different TLR ligands, LPS (1 ng/mL) or TLR2, Pam3CysSK4 (100 ng/mL). As shown in Figure 3A, sarcoidosis AMs exhibit higher expression of IRAK1 at baseline. Similarly, we observed a higher IRAK-M expression in sarcoidosis AMs baseline with no further induction in response to TLR ligands (Fig. 3A). In contrast, AMs of control subjects showed no IRAK-M at baseline, although IRAK-M was induced in response to both TLR ligands (Fig. 3A). Additionally, we determined the expression for IRAK1 and IRAK-M in PBMCs of sarcoidosis subjects as well as healthy controls. Sarcoidosis PBMCs exhibited higher expression level for IRAK1 as compared to healthy controls, but there was no further induction in response to TLR2 challenge (Fig. 3B). Figure 3C&D represent the densitometric values (mean±SEM) of IRAK1 and IRAK-M in AMs, while Figure 3E&F show the densitometric values of IRAK1 and IRAK-M in PBMCs of 6 controls and 10 sarcoidosis patients. Because of the importance of Rip2 in p38 activation (12), we assessed Rip2 protein expression in AMs as well as PBMCs in sarcoidosis and control. A representative blot is shown in Figure 3G from two sarcoidosis subjects (P1&P2) and two controls (C1&C2). Figure 3H shows the cumulative results of densitometric values of Rip2 of 6 controls and 10 sarcoidosis subjects. Figure 3I shows a higher expression of Rip2 in sarcoidosis AMs at baseline and its time dependent rapid induction in response to the TLR2 ligand (Pam3CysSK4) compared to controls. Our data indicate that sustained p38 phosphorylation in sarcoidosis is associated with a higher expression for IRAK1 as well as Rip2 at baseline.

Figure 3. Increased IRAKs and Rip2 expression in sarcoidosis.

AMs from sarcoid subjects and controls were treated with PAM (100 ng/mL) or LPS (1 ng/mL) or left untreated. Whole cell extracts were prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using specific antibodies for IRAK1, IRAK-M, Rip2, β-actin, and p38. (A) Sarcoidosis AMs exhibited higher activated form of IRAK1 as well as higher expression of IRAK-M as compared to control subjects (B) PBMCs from sarcoid subjects also exhibited higher IRAK1 but comparable IRAK-M expression (C) Densitometric values (mean±SEM) expressed as fold change of the ratio of IRAK1/β-actin in AMs of 6 control and 10 sarcoidosis subjects. (D) Densitometric values (mean+SEM) expressed as fold change of the ratio of IRAK-M/β-actin in AMs of 6 control and 10 sarcoidosis subjects. (E) Densitometric values (mean+SEM) expressed as fold change of the ratio of IRAK1/β-actin in PBMCs of 6 control and 10 sarcoidosis subjects (F) Densitometric values (mean+SEM) expressed as fold change of the ratio of IRAK-M/β-actin in PBMCs of 10 control and10 sarcoidosis subjects. (G) Rip2 expression in sarcoidosis and control AMs. Whole cell lysates of AMs of two control subjects (C1&C2) and two sarcoidosis patients (P1&P2) were immunoblotted with Rip2 and p38 antibodies. AMs from sarcoid subjects showed higher expression of Rip2 as compared to healthy controls. (H) Densitometric values (mean+ SEM) expressed as ratio of RIP2/β-actin from 6 controls and 10 sarcoidosis patients. * p- value < 0.05. (I) AMs from controls and sarcoidosis subjects were activated with PAM (100 ng/mL) for indicated time periods. Western blot analysis shows baseline expression of Rip2 and its time- dependent induction with PAM. Representative blots for AMs and PBMCs are shown out of a total of 10 patients and 6 healthy controls.

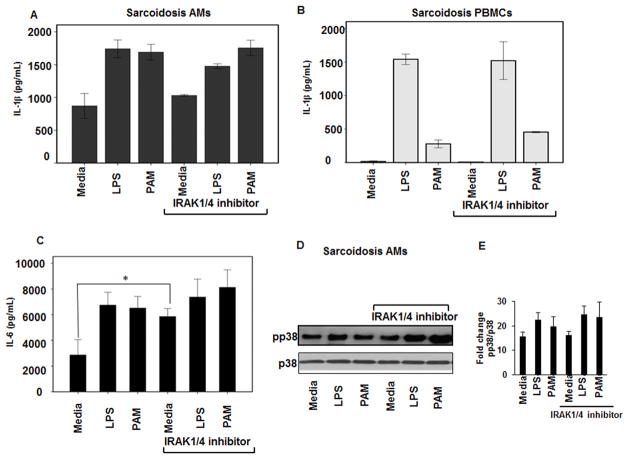

IRAK1/4 inhibitor has no effect on IL-1β and IL-6 production and p38 phosphorylation

There is evidence that IRAKs play a differential role in several inflammatory diseases including, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis (37). Because we observed a higher expression of IRAK1 in sarcoidosis AMs and PBMCs, we postulated that IRAK1/4 inhibitors may have a potential role in inflammatory responses associated with sarcoidosis. We investigated the effect of IRAK1/4 inhibitor on the production of IL-1β and IL-6, two major pro-inflammatory cytokines, in sarcoidosis AMs and PBMCs. First, we determined the dose dependent inhibitory effect of IRAK1/4 inhibitor in control PBMCs in response to LPS. We found that 20μM has an inhibitory effect on LPS mediated IL-6 production (data not shown). Pre-treatment of sarcoidosis AMs or PBMCs with IRAK1/4 inhibitor did not decrease IL-1β production at baseline or in response to TLR2 or TLR4 ligands (Fig. 4A and B). As shown in Figure 4C, we observed an enhanced IL-6 production in sarcoidosis AMs after treatment with IRAK1/4 inhibitor at baseline (p<0.05), but not after challenge with LPS or PAM. Based on our previous work, sustained activation of p38 plays a critical role in sarcoidosis inflammation, hence, we examined the effect of IRAK1/4 inhibitor on p38 phosphorylation both in AMs as well as PBMCs of sarcoidosis subjects. As shown in Figure 4D, pre-treatment of sarcoidosis AMs with IRAK1/4 inhibitor did not decrease phospho p38 both at baseline and after challenge with LPS or PAM. In contrast, we observed an increase in p38 phosphorylation after pretreatment of AMs with IRAK1/4 inhibitor and challenge with LPS or PAM. Although pretreatment with IRAK1/4 inhibitor had tendency to increase p38 phosphorylation at baseline and in response to PAM and LPS, it did not meet the statistical significance. This partly was due to a higher variation of phosphop38 among patients. Cumulative densitometric values (mean±SEM) of Western blots from 6 patients are shown in Figure 4E.

Figure 4. IRAK-1/4 inhibitor does not inhibit IL-1β, IL-6 production and p38 phosphorylation in sarcoidosis AMs and PBMCs.

AMs or PBMCs of sarcoid subjects were pretreated with IRAK-1/4 inhibitor (20μM) for 1h and stimulated with PAM (100 ng/mL) or LPS (1 ng/mL) for 24h. The conditioned medium was assessed for IL-1β and IL-6 using ELISA. IRAK1/4 inhibitor did not significantly inhibit either IL-1β or IL-6 production both in sarcoid AMs (A & C) and IL-1β in PBMCs (B). Data represent mean± SEM from at least six different patients. * Represents p value < 0.05 was considered significant. (D) Sarcoidosis AMs were treated with TLR2, TLR4 ligands in the presence or absence of IRAK1/4 inhibitor. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting using phospho p38 and total p38 (equal loading) antibodies. IRAK1/4 inhibitor did not decrease p38 phosphorylation in AMs. (E) Densitometric values (mean+ SEM) expressed as ratio of pp38/p38 from 6 different sarcoidosis patients.

Combination of IRAK1/4 and Rip2 inhibitors inhibits TLR2 mediated cytokine production in sarcoidosis PBMCs and AMs

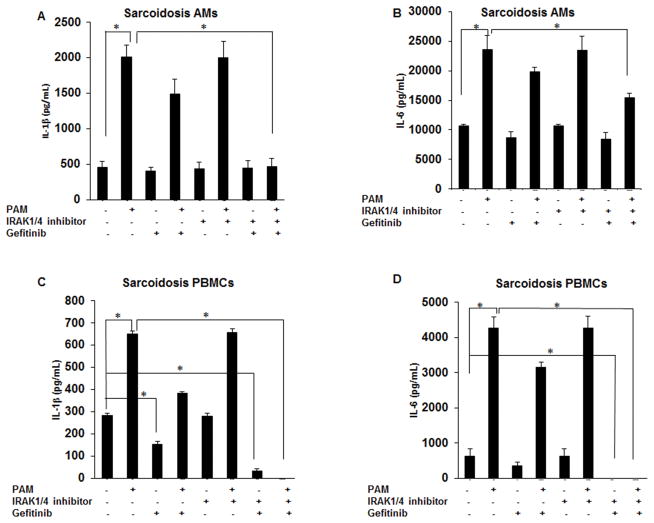

Because IRAK1/4 inhibitor did not significantly decrease IL-1β and IL-6 production at baseline or in response to TLR2 ligand and since both adapter proteins (IRAK1 and Rip2) were highly expressed in sarcoidosis AMs, we investigated if the simultaneous inhibition of both pathways effects cytokine production in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis AMs and PBMCs were cultured in the presence or absence of inhibitors (IRAK1/4 inhibitor and gefitinib, 1μM) for 30 min followed by PAM challenge for 24h. Conditioned media were assessed for IL-1β and IL-6 production. Figure 5A, shows the effect of IRAK1/4 and Rip2 inhibitors alone or in combination in the presence of PAM on IL-1β production in sarcoidosis AMs. As shown, neither inhibitor alone or in combination completely blocked baseline IL-1β release in AMs but PAM induced IL-1β release was inhibited in AMs of sarcoidosis subjects. Figure 5B shows that sarcoidosis AMs released a high amount of IL-6 at baseline with a further increase upon stimulation with TLR2 ligand. Pretreatment with a combination of IRAK1/4 inhibitor and gefitinib led to a reduction baseline as well as PAM-induced IL-6 production (Fig. 5B). Next, we examined the effect of these inhibitors on IL-1β and IL-6 production in PBMCs of sarcoidosis patients. Figure 5C shows IL-1β production in the conditioned media of cultured PBMCs after 24h culture at baseline and after challenge with PAM. As shown, sarcoidosis PBMCs exhibited spontaneous release of IL-1β, yet the amount of IL-1β from PBMC was considerably lower as compared to IL-1β released from AMs. Challenged with PAM PBMCs responded with increased IL-1β production. While IRAK1/4 inhibitor alone did not inhibit IL-1β production, pretreatment with gefitinib significantly decreased baseline IL-1β production in sarcoidosis PBMCs. Interestingly a combination of gefitinib and IRAK1/4 inhibitor significantly decreased both baseline and PAM induced IL-1β production (Fig. 5C). Next, we examined IL-6 production in sarcoidosis PBMCs in response to PAM challenge. Consistent with previous results, we found spontaneous release of IL-6 in the conditioned media of cultured sarcoidosis PBMCs with a significant increase in response to PAM. The combination of IRAK1/4 and Rip2 inhibitors led to a significant decrease in IL-6 production both at baseline and in response to TLR2 activation (Fig. 5D). Data represent mean± SEM from at least ten different experiments. We concluded that a combination of gefitinib and IRAK1/4 inhibitor is more effective to inhibit IL-1β and IL-6 production in PBMCs as compared to AMs.

Figure 5. Effect of gefitinib and IRAK1/4 inhibitor on IL-1β and IL-6 synthesis in sarcoid AMs and PBMCs.

AMs (A&B) or PBMCs (C&D) were pretreated with combination of IRAK1/4 inhibitor (20μM) and gefitinib (1μM) for 30min and then activated with PAM (100 ng/mL) for 24h. Conditioned media were analyzed for IL-1β and IL-6 via ELISA. Data represent mean± SEM from at least ten different patients. * represents p value < 0.05 were considered significant.

Effect of IRAK1/4 inhibitor and gefitinib on gene expression and p38 phosphorylation

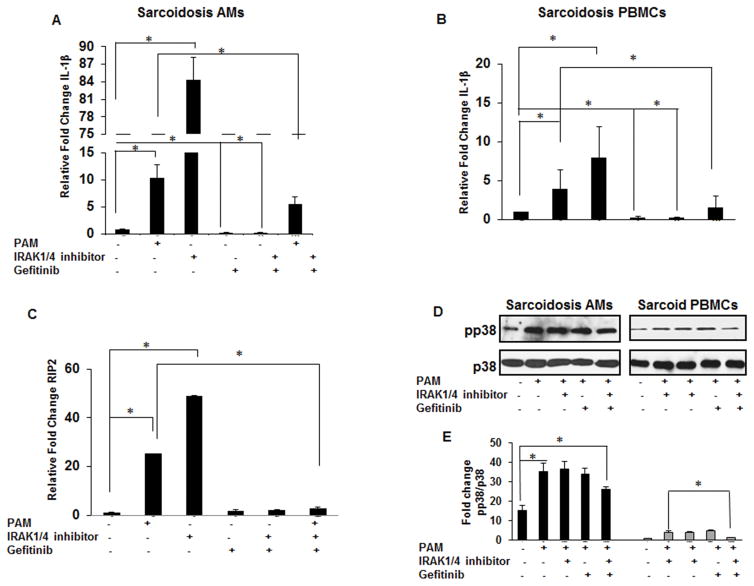

Previous work has shown a spontaneous release of IL-1β from sarcoidosis AMs (20, 38, 39) and current data indicates that IRAK1/4 inhibitor does not block IL-1β release in sarcoidosis AMs or PBMCs. To determine whether this effect is regulated at the transcriptional level we used quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) to evaluated IL-1β mRNA levels. Alveolar macrophages and PBMCs from sarcoidosis subjects were isolated and cultured for 1h in the presence or absence of PAM and either gefitinib or IRAK1/4 inhibitor or a combination of both. As shown in Figure 6A, PAM challenge of sarcoidosis AMs led to an increased expression of IL-1β mRNA (approximately 10 folds). Gefitinib alone decreased basal IL-1β mRNA expression (p-value <0.001). Surprisingly, treatment of AMs with IRAK1/4 inhibitor, even without TLR2 stimulation, led to an exuberant IL-1β mRNA expression (about 80–90 folds). The combination of gefitinib and IRAK1/4 inhibitor blocked baseline as well as TLR2-induced IL-1β mRNA expression (Fig. 6A). Using PBMCs from sarcoidosis patients under the same conditions, we observed a significant reduction of IL-1β gene expression in response to gefitinib alone or in combination with the IRAK1/4 inhibitor (Fig. 6B). To further elucidate the mechanism behind increased IL-1β mRNA expression in response to IRAK1/4 inhibitor, we evaluated the mRNA levels of Rip2 gene using qRT-PCR. As shown in Figure 6C, AMs of sarcoidosis patients responded to TLR2 ligation with an increased expression of Rip2 (25 fold). IRAK1/4 inhibitor alone induced mRNA levels of Rip2 (app. 48 fold) similar to its effect on the induction of IL-1β mRNA. On the other hand, a combination of IRAK1/4 and RIP2 inhibitors strongly inhibited the mRNA levels of Rip2 after stimulation with PAM (Fig. 6C). Next, we examined the effects of gefitinib and IRAK 1/4 inhibitor on p38 phosphorylation in AMs and PBMCs of patients with sarcoidosis. AMs and PBMCs were cultured in the presence and absence of the inhibitors and challenged with PAM for 30 min. Whole cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting to assess p38 phosphorylation. Figure 6D shows the effect of gefitinib, IRAK1/4 inhibitor and a combination of both inhibitors on TLR2 mediated p38 phosphorylation. The AMs of patients with sarcoidosis exhibited active form of p38 at baseline as we previously reported (20). Challenge of sarcoidosis AMs with PAM led to an enhanced p38 phosphorylation. However, pretreatment of AMs with a combination of gefitinib and IRAK1/4 inhibitor significantly reduced p38 activation after PAM challenge. We observed comparable results, when experiments were performed with sarcoidosis PBMCs, yet sarcoidosis PBMCs exhibited a significant lower p38 phosphorylation at baseline (Fig. 6D). Figure 6E shows the cumulative densitometric values of the ratio pp38/p38 of AMs and PBMCs in 10 patients in the presence and absence of both inhibitors at baseline and in response to PAM.

Figure 6. Effect of gefitinib and IRAK inhibitor on the relative gene expression of IL-1β, Rip2 and p38 phosphorylation in sarcoid AMs and PBMCs.

PBMCs and AMs from sarcoidosis subjects were activated with PAM (100 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of IRAK1/4 (20μM) inhibitor or gefitinib (1μM) or combination of IRAK1/4 inhibitor and gefitinb for 1h. RNA was isolated from the cells and subjected to RT-PCR for IL-1β gene expression (A & B) and (C) RIP2 gene expression. Values were normalized to β-actin and are shown as fold change. Data represent mean± SEM from at least five different patients. * represents p value< 0.05. (D) AMs and PBMCs were activated with PAM (100 ng/mL) in presence or absence of inhibitor alone or a combination of both inhibitors for 30 min. Whole cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting to assess the phosphorylation of p38 and total p38 (equal loading). Data presented is a representative blot out of 10 different patients. (E) Densitometric values (mean± SEM) expressed as ratio of pp38/ p38 in AMs and PBMCs samples from 10 patients in presence and absence of both inhibitors at baseline and in response to PAM. * p- value < 0.05.

Dual inhibition of IRAK/4 and Rip2 kinases decreases T-cells activation in sarcoidosis

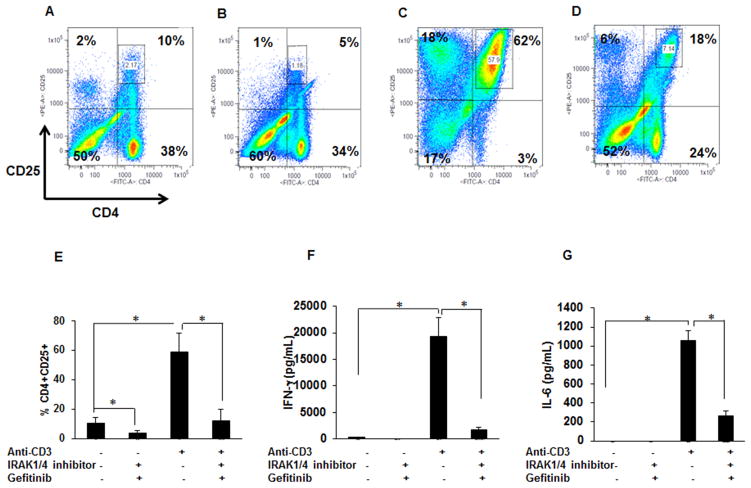

Activated T-cells play a major role in sarcoidosis pathology (40). Hence, we investigated the effect of gefitinib and IRAK1/4 inhibitor on T-cell population in sarcoidosis PBMCs. The activation of CD4+ T-cells was assessed by determining the percentage of CD4+CD25+ cells in gated lymphocyte population. PBMCs were cultured either alone or challenged with anti-CD3 (1μg/mL) in the presence or absence of inhibitors. Figure 7A shows a representative dot plot of a sarcoidosis subject. At baseline 48% of cells express CD4 marker, among those 10% were double positive for CD4+CD25+, a marker for T-cells activation. A combination of IRAK1/4 inhibitor and gefitinib decreased the percentage of CD4 cells (from 48% to 39%) and the CD4+CD25+ activated T-cells to 5% (Fig. 7B). In response to anti-CD3 challenge, percentage of CD4+ cells increased to 65%, among those double positive T cells (CD4+CD25+) increased from 10% to 62% (Fig. 7B and C). Furthermore, a dual inhibition of Rip2 and IRAK1/4 significantly decreased both the percentage of CD4+ and activated T-cells after anti-CD3 challenge from 65% to 42% and 62% to 18% respectively (Fig. 7D). Figure 7E, shows mean± SEM of the percentage of CD4+CD25+ cells of five patients at baseline, in response to anti-CD3 treatment and in presence and absence of both inhibitors. These results indicate that pretreatment with a combination of gefitinib and IRAK1/4 inhibitor decreases significantly the percentage of CD4+CD25+ cells at baseline and in response to anti-CD3 challenge.

Figure 7. Effect of gefitinib and IRAK1/4 inhibitor on CD4+CD25+ cells and IFN-γ and IL-6 production in PBMCs.

PBMCs were cultured at the density of 2×106 cells per well in the presence of rhIL-2 (10 ng/mL) and activated with anti-CD3 (1 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of IRAK1/4 inhibitor (20μM) and gefitinib (1μM). Inhibitors were added 30 min prior to activation. Cells were harvested after 96h of culture and immunostained with fluorescein conjugated antibodies CD4 and CD25 and analyzed by flow cytometry using Flow-jo software. (A–D) Representative scatter plots show FACS analysis of CD4 and CD25 expression of sarcoidosis PBMCs. (A) In unstimulated PBMCs the CD4 and CD25 double positive cells were about 10% in sarcoidosis subjects. (B) Sarcoidosis PBMCs cultured in the presence of gefitinib and IRAK1/4 inhibitor for 96h. The percentage of CD4 and CD25 double positive cells decreased from 10% to 5%. (C) Sarcoidosis PBMCs stimulated with anti-CD3. The percentage of CD4 and CD25 double positive T-cells increased to 62%. (D) Percentage of activated T-cells decreased from 62% after anti-CD3 challenged to 18% in the presence of gefitinib and IRAK1/4inhibitor. Data presented is a representative plot of at least 5 different patients. (E) Percentage of CD4+CD25+ cells (mean±SEM) of five patients at baseline, in response to anti-CD3 treatment and in presence and absence of both inhibitors. (F&G) The conditioned medium was quantified for IFN-γ (F) and IL-6 (G) production. Data represents mean± SEM from at least five different patients. * represents p value < 0.05 and was considered significant. There is a significant increase of IFN- γ and IL-6 after anti-CD3 stimulation which is significantly decreased by pretreatment with a combination of gefitinib and IRAK 1/4 inhibitor.

Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and IL-6 play an important role in Th1 mediated immunopathology of sarcoidosis (41). Next, we examined the effect of IRAK1/4 and gefitinib on IFN-γand IL-6 production in sarcoidosis patients. PBMCs were cultured either alone or challenged with anti-CD3 (1μg/mL) in the presence or absence of inhibitors for 96h. IFN-γ and IL-6 production was assessed in culture supernatants by ELISA. As shown in Fig. 7F, pretreatment of PBMCs with IRAK1/4 and gefitinib resulted in complete inhibition of basal as well as anti-CD3 induced IFN-γ production. Similarly, pretreatment with a combination of IRAK1/4 inhibitor and gefitinib significantly inhibited anti-CD3 induced IL-6 release in sarcoidosis PBMCs (Fig. 7G). These results suggest that a combination of IRAK1/4 and Rip2 inhibitors is effective in inhibiting activated CD4+T-cells as well as IFN-γ and IL-6 production in sarcoidosis PBMCs. Regulatory T cells (Foxp3+ cells) engage in the maintenance of immunological self-tolerance by suppressing active lymphocytes and they play a role in sarcoidosis pathology (42). We assessed the effect of both inhibitors on CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ subset, because one potential mechanism for reduced IFN-γ and IL-6 production in response to inhibitor could have been the modulatory effect on T regulatory (Treg), Supplementary Figure 2 shows that gefitinib and IRAK1/4 inhibitor have no effect on Treg.

Discussion

The exact mechanisms underlying the increased production of Th1 cytokines in sarcoidosis remain unclear (2, 43). Activation of MAPKs is crucial for the synthesis of numerous cytokines and chemokines (23, 44). As we have shown previously, activation of p38 plays a critical role in the regulation of several Th1 cytokines such as IL-12, TNF-α, and interleukin genes in sarcoidosis (20, 24, 45). Here we advance our knowledge by identifying the upstream kinases responsible for p38 activation in sarcoidosis AMs and PBMCs. Activation of several upstream kinases including MKK3/6, MKK4 and AKT/ASK1 may lead to p38 phosphorylation. Conventional activation of p38 occurs through MKK3/6 activation (46–48). Interestingly, our results demonstrate that p38 activation in sarcoidosis was in parallel with increased MKK4 phosphorylation but not with MKK3/6.

The granulomatous inflammation in sarcoidosis has been linked to TLR2 activation (31). To model the inflammation in sarcoidosis, we challenged AMs and PBMCs obtained from subjects with sarcoidosis with a synthetic TLR2 agonist, Pam3CysSK4 and TLR4 ligand (LPS) and dissected the pathway downstream of TLR2/4. Engagement of TLRs induces MyD88-dependent signaling through the activation of IRAK4, which acts upstream of IRAK1 and phosphorylates this kinase (49). IRAK1 also plays an important role in the inflammasome activation (50). Intriguingly, IRAK1-deficient mice still retain LPS-induced NFκB activation (51). We have identified that IRAK1, an immune-modulating kinase, is overexpressed in AMs and PBMCs of sarcoidosis patients compared to healthy controls. A small molecule inhibitor of IRAK1/4, which selectively inhibits its kinase activity in a low μM range (IC50 = 0.75 μM), has been initially developed for autoimmune diseases (52, 53). However, current study indicates that pretreatment of either AMs or PBMCs with IRAK1/4 inhibitor at a pharmacological dose has no significant effect on IL-1β or IL-6 production. Similarly IRAK1/4 inhibitor did not affect p38 phosphorylation at baseline or in response to TLR2/TLR4 challenge in AMs or PBMCs of sarcoidosis patients. These data surprisingly indicate that IRAK1/4 is dispensable in TLR2 and TLR4 mediated IL-1β induction in sarcoidosis AMs and PBMCs, because pharmacological inhibition of IRAK1/4 not only did not reduce IL-1β and IL-6 but increased IL-1β mRNA and IL-6 production in sarcoidosis AMs. One study found that IRAK1 is constitutively modified and it regulates IL-10 gene expression in the PBMCs from atherosclerosis patients (54), suggesting a complex role of IRAK in human disease. IRAK-M is known to play a negative inhibitory role in the TLR pathway (55). We observed higher IRAK-M expression in sarcoidosis PBMCs and AMs as compared to controls. Additionally, IRAK1/4 inhibitor pretreatment did not change the expression of IRAK-M in sarcoidosis PBMCs and AMs (data not shown). Interestingly, pretreatment with IRAK1/4 inhibitor in AMs led to an increase Rip2 mRNA. Another study found a differential role of IRAK1/4 kinase activity and function between human versus mouse using the same IRAK1/4 inhibitor in peripheral dendritic cells of SLE patients (37). Our data support these findings of a dichotomy between the role of IRAK1/4 kinase in human PBMCs and AMs as compared to mouse.

The serine/threonine kinase Rip2 mediates signals for receptors of both innate and adaptive immune responses (17, 56). We identified that Rip2 is highly expressed in sarcoidosis AMs and PBMCs. Rip2 has been shown to play an important role in both TLRs and NOD-signaling, and regulates an optimal T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling (17). However, there is some controversy regarding the role of Rip2 in TLR signaling. While several studies have shown Rip2 involvement in TLR-mediated MAP kinases and NF-kB activation as well as a role in TCR mediated signaling and T-cell differentiation (22, 56), others using knockout mice showed lack of a pivotal role of Rip2 in TLR signaling (57). In contrast to previous studies using knockout mice, we show overexpression and gain of function of Rip2 kinase in sarcoidosis. Activation of p38 by Rip2 is associated with both MKK3/6 and MKK4 MAPK kinases (12). Interestingly, recently it has been shown that SB203580, which previously was thought to be a specific p38 inhibitor, also inhibits Rip2 kinase (58). Our previous study indicated that SB203580 significantly modulates the inflammatory responses in AMs and PBMCs of sarcoidosis patients (20). This effect might have been due to Rip2 kinase inhibition beside p38 blockade.

Gefitinib, a EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor has been shown to be a specific inhibitor of Rip2 kinase in macrophages (59). Thus, we determined the effect of dual inhibition of IRAK1/4 and Rip2 on the activation of p38 and inflammatory cytokine production in AMs and PBMCs of sarcoidosis patients. None of inhibitor was cell toxic as determined by MTT assay. Neither inhibitors targeting IRAK1/4 or Rip2 alone could abrogate IL-1β and IL-6 production in sarcoidosis AMs both at baseline and in response to TLR2 (PAM) or TLR4 ligand (LPS). The combination of IRAK1/4 and Rip2 inhibitors had a moderate effect on IL-1β and IL-6 production in AMs. In contrast to AMs, both the basal as well as PAM-induced IL-1β and IL-6 production in PBMCs of sarcoidosis patients was significantly inhibited by a combination of IRAK1/4 inhibitor and gefitinib. However, looking at the gene expression, a combination of IRAK1/4 inhibitor and gefitinib inhibited IL-1β mRNA in sarcoidosis AMs and PBMCs. Similar to the decreased cytokine production, a combination of IRAK1/4 inhibitor and gefitinib decreased the activation of p38 in PBMCs as well as a moderate inhibition of p38 phosphorylation in AMs. The synergistic effects of IRAK1/4 and Rip2 inhibitors on cytokine release in PBMCs of sarcoidosis patients may be due to less sustained activation of p38 MAPK and lower expression of Rip2 kinase as compared to AMs. Further studies need to determine whether the inhibitory effect of gefitinib on cytokine production is solely due to Rip2 or additional EGFR inhibition. We observed that AMs compared to PBMCs of the same patient exhibit higher cytokine production and higher phospho p38 activity. This could be due to the fact that tissue resident macrophages exhibit a more inflammatory phenotype or it may be due to a mixed population in PBMCs.

P38α MAPK is the major isoform in T cells and is involved in signaling of IFN-γ production by Th1 cells (44). Studies have demonstrated that the p38 pathway is involved in the production of IFN-γ by CD4 and CD8 T-cells (60). Although MKK3, MKK4 and MKK6 MAPK kinases can activate p38 in T-cells, it has been shown that there is a stimuli dependent preferential activation of these kinases (61). In sarcoidosis, lymphocytes (T and B cells) and alveolar macrophages (AMs) play a role in the disease process. In T-cells, p38 phosphorylation occurs through a non-canonical alternative pathway, Lck-ZAP70-mediated phosphorylation at Tyr-323(62). Tyr-323 phosphorylation has been shown to be the major mechanism of TCR-induced p38 activation and IFN-γ production by T-cells. In the current study, we did not detect significant p38 Tyr-323 activation in BALs or PBMCs of patients with sarcoidosis (data not shown).

In our study the sarcoidosis PBMCs responded to anti-CD3 stimulation with increased IL-6 and IFN-γ production. Similar to TLR2 mediated IL-6 production, the combination of IRAK1/4 inhibitor and gefitinib decreased the basal as well as TCR-induced IFN-γ and IL-6 production in sarcoidosis PBMCs. In addition, we evaluated the effect of these inhibitors on the expression of the T-cell activation marker CD25. Pretreatment of PBMCs with IRAK1/4 inhibitor and gefitinib decreased the expression of CD25 and reduced the percentage of CD4+CD25+ activated cells. Previously, it has been shown that part of sarcoidosis pathology is related to deregulation of Treg (40, 42). In our system reduced IFN-γ and IL-6 production was not due to the effect of inhibitor on number of Tregs. These results show that dual inhibition of IRAK1/4 and Rip2 kinases decreases the percentage of activated T-cells and IFN-γ and IL-6 production in PBMCs.

Thus, our results demonstrate that the combination of IRAK1/4 and Rip2 inhibitors had a significant inhibitory effect on the inflammatory immune response exhibited by sarcoidosis PBMCs, but only a moderate effect on cytokine production in AMs. Since the AMs from sarcoidosis patients showed increased expression of IRAK1 and Rip2 kinases and dual inhibition of both modulated important Th1 cytokines, both kinases may play a role in pathogenesis of sarcoidosis. Alveolar macrophages may show a more inflammatory phenotype compared to peripheral monocytes due to a higher exposure to environmental toxins or local unidentified antigens. The findings of our study further confirm that there is an increased local activation of BAL cells in lungs of sarcoidosis patients as compared to PBMCs. This could be due to differential regulation of MAPK kinases in the sarcoidosis AMs and PBMCs. To our knowledge this study is the first and only study performed in human derived lung cells assessing a systemic inflammatory disease. Our findings suggest that beside MKP-1 dysregulation leading to sustained p38 activation in sarcoidosis, the activation of MKK4 via a pathway involving IRAK1 and Rip2, additionally regulates p38 activation and cytokine production in sarcoidosis (20). In addition, the findings of the study suggest that targeting IRAK1/4 and Rip2 with a pharmacological agent may modulate both the innate and adaptive immune signals in inflammatory diseases. Our study advanced our previous understanding how the kinase(s) upstream of p38 are activated and provides a mechanistic pathway that could be valuable for the development of new therapeutic targets for sarcoidosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant (R01HL113508 (LS) and American lung Association (LS) and as well as the Department of Medicine and the Center for Molecular Medicine and Genetics, Wayne State University School of Medicine (LS). The Microscopy, Imaging and Cytometry Resources Core is supported, in part, by NIH Center grant P30 CA022453 to the Karmanos Cancer Institute at Wayne State University, and the Perinatology Research Branch of the National Institutes of Child Health and Development at Wayne State University.

We thank Dr. Gabriel Nunez, University of Michigan, for invaluable discussion in completing this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure: None of the authors of this manuscript had any financial relationship with a commercial company.

References

- 1.Baughman RP, Culver DA, Judson MA. A concise review of pulmonary sarcoidosis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011;183:573–581. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-0865CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerke AK, Hunninghake G. The immunology of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29:379–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moller DR, Chen ES. Genetic basis of remitting sarcoidosis: triumph of the trimolecular complex? American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2002;27:391–395. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0164PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunninghake GW, Crystal RG. Pulmonary sarcoidosis: a disorder mediated by excess helper T-lymphocyte activity at sites of disease activity. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:429–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198108203050804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fritz JH, Le Bourhis L, Sellge G, Magalhaes JG, Fsihi H, Kufer TA, Collins C, Viala J, Ferrero RL, Girardin SE, Philpott DJ. Nod1-mediated innate immune recognition of peptidoglycan contributes to the onset of adaptive immunity. Immunity. 2007;26:445–459. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uematsu S, Akira S. Innate immune recognition of viral infection. Uirusu. 2006;56:1–8. doi: 10.2222/jsv.56.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao Z, Henzel WJ, Gao X. IRAK: a kinase associated with the interleukin-1 receptor. Science. 1996;271:1128–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5252.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosati O, Martin MU. Identification and characterization of murine IRAK-M. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2002;293:1472–1477. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, Commane M, Burns C, Vithalani K, Cao Z, Stark GR. Mutant cells that do not respond to interleukin-1 (IL-1) reveal a novel role for IL-1 receptor-associated kinase. Molecular and cellular biology. 1999;19:4643–4652. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas JA, Allen JL, Tsen M, Dubnicoff T, Danao J, Liao XC, Cao Z, Wasserman SA. Impaired cytokine signaling in mice lacking the IL-1 receptor-associated kinase. J Immunol. 1999;163:978–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Picard C, Puel A, Bonnet M, Ku CL, Bustamante J, Yang K, Soudais C, Dupuis S, Feinberg J, Fieschi C, Elbim C, Hitchcock R, Lammas D, Davies G, Al-Ghonaium A, Al-Rayes H, Al-Jumaah S, Al-Hajjar S, Al-Mohsen IZ, Frayha HH, Rucker R, Hawn TR, Aderem A, Tufenkeji H, Haraguchi S, Day NK, Good RA, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Ozinsky A, Casanova JL. Pyogenic bacterial infections in humans with IRAK-4 deficiency. Science. 2003;299:2076–2079. doi: 10.1126/science.1081902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacquet S, Nishino Y, Kumphune S, Sicard P, Clark JE, Kobayashi KS, Flavell RA, Eickhoff J, Cotten M, Marber MS. The role of RIP2 in p38 MAPK activation in the stressed heart. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:11964–11971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707750200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarthy JV, Ni J, Dixit VM. RIP2 is a novel NF-kappaB-activating and cell death-inducing kinase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:16968–16975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Navas TA, Baldwin DT, Stewart TA. RIP2 is a Raf1-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:33684–33690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Humphries F, Yang S, Wang B, Moynagh PN. RIP kinases: key decision makers in cell death and innate immunity. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:225–236. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jun JC, Cominelli F, Abbott DW. RIP2 activity in inflammatory disease and implications for novel therapeutics. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2013;94:927–932. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0213109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chin AI, Dempsey PW, Bruhn K, Miller JF, Xu Y, Cheng G. Involvement of receptor-interacting protein 2 in innate and adaptive immune responses. Nature. 2002;416:190–194. doi: 10.1038/416190a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi K, Inohara N, Hernandez LD, Galan JE, Nunez G, Janeway CA, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. RICK/Rip2/CARDIAK mediates signalling for receptors of the innate and adaptive immune systems. Nature. 2002;416:194–199. doi: 10.1038/416194a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spiteri MA, Poulter LW, Geraint-James D. The macrophage in sarcoid granuloma formation. Sarcoidosis. 1989;6(Suppl 1):12–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rastogi R, Du W, Ju D, Pirockinaite G, Liu Y, Nunez G, Samavati L. Dysregulation of p38 and MKP-1 in response to NOD1/TLR4 stimulation in sarcoid bronchoalveolar cells. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011;183:500–510. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201005-0792OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathew S, Bauer KL, Fischoeder A, Bhardwaj N, Oliver SJ. The anergic state in sarcoidosis is associated with diminished dendritic cell function. J Immunol. 2008;181:746–755. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prior C, Knight RA, Herold M, Ott G, Spiteri MA. Pulmonary sarcoidosis: patterns of cytokine release in vitro. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:47–53. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09010047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong C, Davis RJ, Flavell RA. MAP kinases in the immune response. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:55–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.091301.131133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inoue T, Boyle DL, Corr M, Hammaker D, Davis RJ, Flavell RA, Firestein GS. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3 is a pivotal pathway regulating p38 activation in inflammatory arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5484–5489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509188103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rincon M, Enslen H, Raingeaud J, Recht M, Zapton T, Su MS, Penix LA, Davis RJ, Flavell RA. Interferon-gamma expression by Th1 effector T cells mediated by the p38 MAP kinase signaling pathway. The EMBO journal. 1998;17:2817–2829. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, Baughman R, Cordier JF, du Bois R, Eklund A, Kitaichi M, Lynch J, Rizzato G, Rose C, Selroos O, Semenzato G, Sharma OP. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999;16:149–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samavati L, Rastogi R, Du W, Huttemann M, Fite A, Franchi L. STAT3 tyrosine phosphorylation is critical for interleukin 1 beta and interleukin-6 production in response to lipopolysaccharide and live bacteria. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:1867–1877. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antal-Szalmas P, Strijp JA, Weersink AJ, Verhoef J, Van Kessel KP. Quantitation of surface CD14 on human monocytes and neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61:721–728. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.6.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ziegler-Heitbrock L. The CD14+ CD16+ blood monocytes: their role in infection and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:584–592. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0806510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Striz I, Zheng L, Wang YM, Pokorna H, Bauer PC, Costabel U. Soluble CD14 is increased in bronchoalveolar lavage of active sarcoidosis and correlates with alveolar macrophage membrane-bound CD14. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1995;151:544–547. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.2.7531099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen ES, Song Z, Willett MH, Heine S, Yung RC, Liu MC, Groshong SD, Zhang Y, Tuder RM, Moller DR. Serum amyloid A regulates granulomatous inflammation in sarcoidosis through Toll-like receptor-2. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 181:360–373. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200905-0696OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pabst S, Baumgarten G, Stremmel A, Lennarz M, Knufermann P, Gillissen A, Vetter H, Grohe C. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 polymorphisms are associated with a chronic course of sarcoidosis. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2006;143:420–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ichijo H, Nishida E, Irie K, ten Dijke P, Saitoh M, Moriguchi T, Takagi M, Matsumoto K, Miyazono K, Gotoh Y. Induction of apoptosis by ASK1, a mammalian MAPKKK that activates SAPK/JNK and p38 signaling pathways. Science. 1997;275:90–94. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zarubin T, Han J. Activation and signaling of the p38 MAP kinase pathway. Cell research. 2005;15:11–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobayashi KS, Chamaillard M, Ogura Y, Henegariu O, Inohara N, Nunez G, Flavell RA. Nod2-dependent regulation of innate and adaptive immunity in the intestinal tract. Science. 2005;307:731–734. doi: 10.1126/science.1104911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gottipati S, Rao NL, Fung-Leung WP. IRAK1: a critical signaling mediator of innate immunity. Cell Signal. 2008;20:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiang EY, Yu X, Grogan JL. Immune complex-mediated cell activation from systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis patients elaborate different requirements for IRAK1/4 kinase activity across human cell types. J Immunol. 2011;186:1279–1288. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kline JN, Schwartz DA, Monick MM, Floerchinger CS, Hunninghake GW. Relative release of interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist by alveolar macrophages. A study in asbestos-induced lung disease, sarcoidosis, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 1993;104:47–53. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steffen M, Petersen J, Oldigs M, Karmeier A, Magnussen H, Thiele HG, Raedler A. Increased secretion of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1-beta, and interleukin-6 by alveolar macrophages from patients with sarcoidosis. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 1993;91:939–949. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(93)90352-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyara M, Amoura Z, Parizot C, Badoual C, Dorgham K, Trad S, Kambouchner M, Valeyre D, Chapelon-Abric C, Debré P. The immune paradox of sarcoidosis and regulatory T cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:359–370. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sahashi K, Ina Y, Takada K, Sato T, Yamamoto M, Morishita M. Significance of interleukin 6 in patients with sarcoidosis. CHEST Journal. 1994;106:156–160. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taflin C, Miyara M, Nochy D, Valeyre D, Naccache JM, Altare F, Salek-Peyron P, Badoual C, Bruneval P, Haroche J. FoxP3+ regulatory T cells suppress early stages of granuloma formation but have little impact on sarcoidosis lesions. The American journal of pathology. 2009;174:497–508. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hata M, Sugisaki K, Miyazaki E, Kumamoto T, Tsuda T. Circulating IL-12 p40 is increased in the patients with sarcoidosis, correlation with clinical markers. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan) 2007;46:1387–1393. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ashwell JD. The many paths to p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:532–540. doi: 10.1038/nri1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Merritt C, Enslen H, Diehl N, Conze D, Davis RJ, Rincon M. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in vivo selectively induces apoptosis of CD8(+) but not CD4(+) T cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:936–946. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.936-946.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hsieh CC, Kuro-o M, Rosenblatt KP, Brobey R, Papaconstantinou J. The ASK1-Signalosome regulates p38 MAPK activity in response to levels of endogenous oxidative stress in the Klotho mouse models of aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2:597–611. doi: 10.18632/aging.100194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pan J, Chang Q, Wang X, Son Y, Zhang Z, Chen G, Luo J, Bi Y, Chen F, Shi X. Reactive oxygen species-activated Akt/ASK1/p38 signaling pathway in nickel compound-induced apoptosis in BEAS 2B cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 23:568–577. doi: 10.1021/tx9003193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohkusu-Tsukada K, Tominaga N, Udono H, Yui K. Regulation of the maintenance of peripheral T-cell anergy by TAB1-mediated p38 alpha activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6957–6966. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.16.6957-6966.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li S, Strelow A, Fontana EJ, Wesche H. IRAK-4: a novel member of the IRAK family with the properties of an IRAK-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5567–5572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082100399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fernandes-Alnemri T, Kang S, Anderson C, Sagara J, Fitzgerald KA, Alnemri ES. Cutting edge: TLR signaling licenses IRAK1 for rapid activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Immunol. 2013;191:3995–3999. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swantek JL, Tsen MF, Cobb MH, Thomas JA. IL-1 receptor-associated kinase modulates host responsiveness to endotoxin. The Journal of Immunology. 2000;164:4301–4306. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Z, Wesche H, Stevens T, Walker N, Yeh WC. IRAK-4 inhibitors for inflammation. Current topics in medicinal chemistry. 2009;9:724–737. doi: 10.2174/156802609789044407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Z, Liu J, Sudom A, Ayres M, Li S, Wesche H, Powers JP, Walker NP. Crystal structures of IRAK-4 kinase in complex with inhibitors: a serine/threonine kinase with tyrosine as a gatekeeper. Structure. 2006;14:1835–1844. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang Y, Li T, Sane DC, Li L. IRAK1 serves as a novel regulator essential for lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-10 gene expression. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:51697–51703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kobayashi K, Hernandez LD, Galan JE, Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. IRAK-M is a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell. 2002;110:191–202. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00827-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang D, Lin J, Han J. Receptor-interacting protein (RIP) kinase family. Cellular & molecular immunology. 2010;7:243–249. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2010.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park JH, Kim YG, McDonald C, Kanneganti TD, Hasegawa M, Body-Malapel M, Inohara N, Nunez G. RICK/RIP2 mediates innate immune responses induced through Nod1 and Nod2 but not TLRs. J Immunol. 2007;178:2380–2386. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Godl K, Wissing J, Kurtenbach A, Habenberger P, Blencke S, Gutbrod H, Salassidis K, Stein-Gerlach M, Missio A, Cotten M. An efficient proteomics method to identify the cellular targets of protein kinase inhibitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100:15434–15439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2535024100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tigno-Aranjuez JT, Asara JM, Abbott DW. Inhibition of RIP2’s tyrosine kinase activity limits NOD2-driven cytokine responses. Genes & development. 2010;24:2666–2677. doi: 10.1101/gad.1964410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rincon M, Pedraza-Alva G. JNK and p38 MAP kinases in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Immunological reviews. 2003;192:131–142. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brancho D, Tanaka N, Jaeschke A, Ventura JJ, Kelkar N, Tanaka Y, Kyuuma M, Takeshita T, Flavell RA, Davis RJ. Mechanism of p38 MAP kinase activation in vivo. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1969–1978. doi: 10.1101/gad.1107303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salvador JM, Mittelstadt PR, Belova GI, Fornace AJ, Jr, Ashwell JD. The autoimmune suppressor Gadd45alpha inhibits the T cell alternative p38 activation pathway. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:396–402. doi: 10.1038/ni1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.