Abstract

Psychostimulants have an impact on protein synthesis, although underlying molecular mechanisms are unclear. Eukaryotic initiation factor 2α-subunit (eIF2α) is a key player in initiation of protein translation and is regulated by phosphorylation. While this factor is sensitive to changing synaptic input and is critical for synaptic plasticity, its sensitivity to stimulants is poorly understood. Here we systematically characterized responses of eIF2α to a systemic administration of the stimulant amphetamine (AMPH) in dopamine responsive regions of adult rat brains. Intraperitoneal injection of AMPH at 5 mg/kg increased eIF2α phosphorylation at serine 51 in the striatum. This increase was transient. In the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), AMPH induced a relatively delayed phosphorylation of the factor. Pretreatment with a dopamine D1 receptor antagonist SCH23390 blocked the AMPH-stimulated eIF2α phosphorylation in both the striatum and mPFC. Similarly, a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist eticlopride reduced the effect of AMPH in the two regions. Two antagonists alone did not alter basal eIF2α phosphorylation. AMPH and two antagonists did not change the amount of total eIF2α proteins in both regions. These results demonstrate the sensitivity of eIF2α to stimulant exposure. AMPH possesses the ability to stimulate eIF2α phosphorylation in striatal and mPFC neurons in vivo in a D1 and D2 receptor-dependent manner.

Keywords: Initiation factor, protein synthesis, translation, caudate putamen, nucleus accumbens, dopamine receptor

1. Introduction

Protein biosynthesis is a tightly controlled process in which translation is an essential part. Four sequential steps are involved in the translation phase: activation, initiation, elongation, and termination. Among these steps, the initiation is the rate-limiting step and is subjected to the activity-dependent regulation (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2009). Eukaryotic initiation factors (eIFs) are a group of proteins required for the initiation of translation. These factors are subjected to the regulation by two independent ways. First, mTOR complex 1 regulates the eIF4F complex to control the initiation (Sonenberg and Hinnebusch, 2009; Laplante and Sabatini, 2012). Second, eIF2α-subunit (eIF2α) is regulated via a phosphorylation mechanism. That is, phosphorylation of eIF2α at a specific residue (serine 51) prevents eIF2α from forming a ternary complex with GTP and the initiator Met-tRNA, which results in suppression of general translation (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2009). However, paradoxically, phosphorylation of eIF2α also selectively upregulates translation of a subset of mRNAs that contain upstream open reading frames in their 5′ untranslated region (Dever, 2002; Hinnebusch, 2005; Jackson et al., 2010). Phosphorylation of eIF2α at serine 51 is regulated by four serine/threonine protein kinases. These kinases are 1) protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK, also known as EIF2AK3) (Wek et al., 2006) which is activated in response to a variety of endoplasmic reticulum stresses (Harding et al., 1999), 2) double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR, or EIF2AK2), 3) general control non-derepressible-2 (GCN2, or EIF2AK4), and 4) heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI, or EIF2AK1) (Donnelly et al., 2013; Trinh and Klann, 2013). In contrast to eIF2α kinases, protein phosphatase 1 dephosphorylates eIF2α (Novoa et al., 2001). Both phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of eIF2α have been implicated in modulating synaptic plasticity (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2009; Di Prisco et al., 2014). It is generally believed that phosphorylation of eIF2α is an activity-regulated event and participates in the translational control of cellular signaling and synaptic plasticity related to various neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2009; Jian et al., 2014).

The psychostimulant amphetamine (AMPH) impacts gene expression (mRNAs or proteins) in neurons. These inducible genomic responses were mainly investigated in the striatum and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), two dopamine responsive areas in limbic reward circuits critical for addictive properties of drugs of abuse. Early data show that AMPH stimulated or inhibited different sets of gene expression in these regions (Gerfen et al., 1990; Graybiel et al., 1990; Ruskin and Marshall, 1994; Wang and McGinty, 1995b). These alterations in either up- or downregulation of gene expression are thought to contribute to long-term adaptations in the limbic reward system, leading to enduring drug seeking behavior (Nestler, 2001; McClung and Nestler, 2008). As a key factor regulating protein translation, eIF2α may be sensitive to stimulants and may play a role in regulating the effect of drugs on gene expression at the posttranscriptional phase. However, to date it has not been investigated whether AMPH has an impact on phosphorylation and/or expression of eIF2α in the dopamine-innervated areas.

In this study, we set forth to investigate whether dopamine stimulation has any impact on phosphorylation and expression of eIF2α in adult rat brains in vivo. The effect of a single systemic injection of AMPH on phosphorylated and total amounts of eIF2α proteins was examined in the striatum and mPFC. We first carried out a study to examine the effect of AMPH at a lower and a higher dose. We then conducted a time-course study to define the temporal property of AMPH in altering eIF2α. Finally, we evaluated the role of dopamine D1 receptors (D1Rs) and D2 receptors (D2Rs) in mediating the effect of AMPH by testing the effect of a D1R or D2R antagonist on the AMPH-stimulated eIF2α phosphorylation.

2. Results

2.1. AMPH enhances eIF2α phosphorylation in the striatum

We first carried out a study to investigate the effect of AMPH on eIF2α phosphorylation and expression in the striatum and mPFC. Rats received a single dose of AMPH at 0.5 or 5 mg/kg (i.p.) and were sacrificed 20 min after AMPH administration. The striatum and mPFC were removed for Western blot analysis of changes in p-eIF2α and total eIF2α proteins in these regions. We found that AMPH dose-dependently increased phosphorylation of eIF2α in the striatum. While AMPH at a lower dose (0.5 mg/kg) did not significantly alter p-eIF2α levels, the stimulant at a higher dose (5 mg/kg) markedly elevated p-eIF2α (Fig. 1A). In the mPFC, AMPH at either dose induced an insignificant change in p-eIF2α signals (Fig. 1B). AMPH at both doses showed no effect on a total cellular amount of eIF2α proteins in the striatum and mPFC. These data demonstrate that acute administration of AMPH at 5 mg/kg enhances eIF2α phosphorylation in the striatum. Since total eIF2α levels were not changed, increased p-eIF2α signals reflect an increased phosphorylation rate of the protein in response to AMPH.

Figure 1. Effects of AMPH at a lower and a higher dose on phosphorylation and expression of eIF2α in the striatum and mPFC.

A, Effects of AMPH on phosphorylation and expression of eIF2α in the striatum. B, Effects of AMPH on phosphorylation and expression of eIF2α in the mPFC. Note that AMPH only at a higher dose increased p-eIF2α levels in the striatum. Representative immunoblots are shown to the left of the quantified data. Rats were given an i.p. injection of saline (Sal) or AMPH at 0.5 or 5 mg/kg and were sacrificed 20 min after drug injection for Western blot analysis of changes in p-eIF2α and eIF2α expression. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4–7 per group). *p < 0.05 versus saline (one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc test).

2.2. Effects of AMPH on eIF2α phosphorylation: a time-course study

We next conducted a time-course study to profile temporal properties of the AMPH effect on eIF2α phosphorylation and expression in the striatum and mPFC. To this end, rats were subjected to a single injection of saline or AMPH. They were then sacrificed at different time points (1, 3, or 6 h) after drug administration for harvesting brain tissue for Western blot analysis. In the striatum, as shown in Fig. 2A and 2B, AMPH enhanced p-eIF2α levels 1 h after drug injection, similar to the above observation at 20 min. At 3 h, AMPH still increased p-eIF2α to a significant level (P < 0.05). However, at 6 h, p-eIF2α levels were not altered in AMPH-treated rats as compared to saline-treated rats. At all time points surveyed, total eIF2α levels showed an insignificant change between AMPH- and saline-treated groups (Fig. 2A and 2C). Clearly, AMPH induces a time-limited and reversible increase in eIF2α phosphorylation in striatal neurons.

Figure 2. Effects of AMPH at different time points on phosphorylation and expression of eIF2α in the striatum.

A, Representative immunoblots illustrating effects of AMPH at different times on phosphorylation and expression of eIF2α. B and C, Quantification of p-eIF2α (B) and eIF2α (C) immunoblots. Note that AMPH induced a transient and reversible increase in p-eIF2α levels. Rats were given an i.p. injection of saline or AMPH (5 mg/kg) and were sacrificed at different time points (1, 3 or 6 h) after drug injection. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4–6 per group). *p < 0.05 versus saline (two-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc test).

In the same rats, we examined the time-dependent effect of AMPH in the mPFC. Remarkably, AMPH at 1 h significantly elevated p-eIF2α levels (Fig. 3A and 3B). At 3 h, p-eIF2α remained at a higher level in AMPH-treated than saline-treated group. At 6 h, p-eIF2α was no longer increased in AMPH-treated rats relative to saline-treated rats. Total eIF2α levels were not altered by AMPH at all three time points (Fig. 3A and 3C). These results indicate that AMPH induces a relatively delayed and reversible increase in eIF2α phosphorylation in mPFC neurons.

Figure 3. Effects of AMPH at different time points on phosphorylation and expression of eIF2α in the mPFC.

A, Representative immunoblots illustrating effects of AMPH at different times on phosphorylation and expression of eIF2α. B and C, Quantification of p-eIF2α (B) and eIF2α (C) immunoblots. Note that AMPH induced a reversible increase in p-eIF2α levels. Rats were given an i.p. injection of saline or AMPH (5 mg/kg) and were sacrificed at different time points (1, 3 or 6 h) after drug injection. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4–6 per group). *p < 0.05 versus saline (two-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc test).

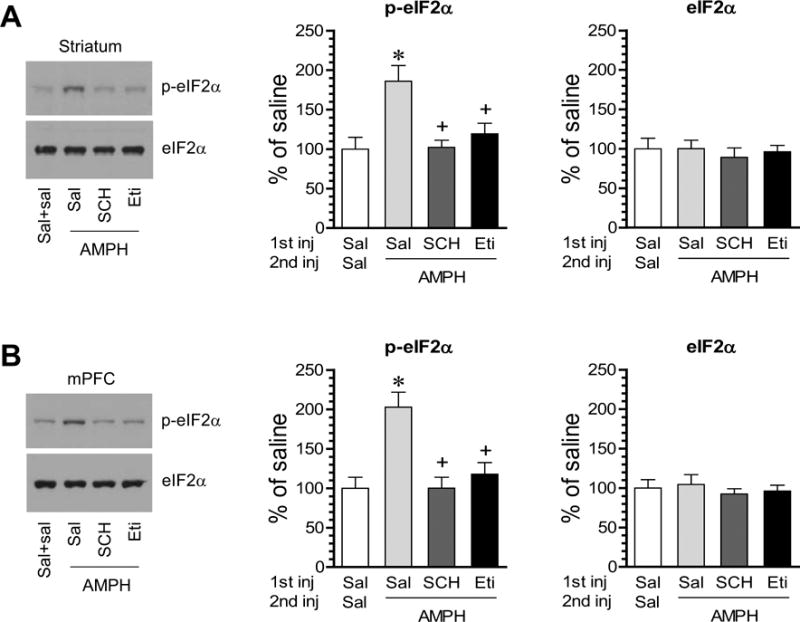

2.3. Effects of D1R and D2R antagonists on AMPH-stimulated eIF2α phosphorylation

To determine the receptor that mediates the effect of AMPH, we carried out a pharmacological study. AMPH is well known to stimulate dopamine release in dopamine responsive regions (Butcher et al., 1988; Moghaddam et al., 1990). We thus evaluated the role of D1Rs and D2Rs in mediating the AMPH-stimulated eIF2α phosphorylation. The D1R antagonist SCH23390 (0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) or the D2R antagonist eticlopride (0.5 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered 20 min prior to AMPH (5 mg/kg, i.p.). Rats were then sacrificed 1 h after AMPH injection. SCH23390 completely blocked the phosphorylation response of eIF2α to AMPH in the striatum (Fig. 4A). Similarly, in the presence of eticlopride, AMPH produced a significantly less increase in eIF2α phosphorylation. In the mPFC, similar results were observed. Pretreatment with SCH23390 or eticlopride reduced the AMPH-stimulated eIF2α phosphorylation (Fig. 4B). There was no significant change in total eIF2α proteins following all drug treatments. These results indicate that activation of both D1Rs and D2Rs is required for phosphorylation responses of eIF2α to AMPH in striatal and mPFC neurons.

Figure 4. Effects of D1R and D2R antagonists on the AMPH-stimulated eIF2α phosphorylation in the striatum and mPFC.

A and B, Effects of SCH23390 (SCH) and eticlopride (Eti) on the AMPH-stimulated eIF2α phosphorylation in the striatum (A) and mPFC (B). Note that both SCH23390 and eticlopride blocked an increase in p-eIF2α proteins in response to AMPH. Representative immunoblots are shown to the left of the quantified data. Rats were given the first i.p. injection of saline, SCH23390 (0.5 mg/kg) or eticlopride (0.5 mg/kg) 20 min prior to the second i.p. injection of saline or AMPH (5 mg/kg) and were sacrificed 1 h after AMPH injection. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4 per group). *p < 0.05 versus saline (Sal) + saline; +p <0.05 versus saline + AMPH (one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc test).

To determine the effect of D1R and D2R antagonists on basal eIF2α phosphorylation, we injected rats with SCH23390 and eticlopride at 0.5 mg/kg (i.p.) and sacrificed rats 1 h after agent injection. Both antagonists had no significant impact on basal levels of p-eIF2α in the striatum (Fig. 5A). Similar results were observed in the mPFC (Fig. 5B). The effectiveness of these agents after a systemic injection was confirmed by the observations from the same samples that SCH23390 reduced AMPA glutamate receptor GluA1 phosphorylation at serine 845 (S845), whereas eticlopride elevated it in the striatum (Fig. 5C), a known fact that D1Rs and D2Rs stimulate and inhibit S845 phosphorylation in striatal neurons, respectively (Snyder et al., 2000; Hakansson et al., 2006). These data suggest that D1Rs and D2Rs play an insignificant role in the regulation of basal eIF2α phosphorylation in striatal and mPFC neurons.

Figure 5. Effects of D1R and D2R antagonists on basal eIF2α phosphorylation in the striatum and mPFC.

A and B, Effects of SCH23390 (SCH) and eticlopride (Eti) on basal eIF2α phosphorylation in the striatum (A) and mPFC (B). C, Effects of SCH23390 and eticlopride on GluA1 S845 phosphorylation in the striatum. Representative immunoblots are shown to the left of the quantified data. Rats were given an i.p. injection of saline (Sal), SCH23390 (0.5 mg/kg), or eticlopride (0.5 mg/kg) and were sacrificed 1 h after drug injection. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4 per group). *p < 0.05 versus saline (one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc test).

3. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the regulation of eIF2α phosphorylation and expression by dopamine in adult rat brains in vivo. We found that an acute systemic injection of AMPH at a higher but not lower dose increased eIF2α phosphorylation in the striatum. AMPH also induced a transient elevation of eIF2α phosphorylation in the striatum and mPFC. Blockade of D1Rs or D2Rs did not alter basal eIF2α phosphorylation. However, both D1R and D2R antagonists significantly blocked the AMPH-stimulated eIF2α phosphorylation. These results indicate that AMPH possesses the ability to upregulate eIF2α phosphorylation in dopamine responsive regions via a mechanism involving D1R and D2R activation.

While we attempted to examine the effect of AMPH on both phosphorylation and expression of eIF2α, we observed significant changes only in phosphorylation status but not expression of the factor. This indicates that the stimulant preferentially affects the phosphorylation rate of eIF2α. The effect of AMPH in the striatum was clearly seen at a higher dose (5 mg/kg) but not a lower dose (0.5 mg/kg). In addition, AMPH enhanced eIF2α phosphorylation in a time-related manner. In the striatum, an increase in eIF2α phosphorylation was seen as early as 20 min after AMPH injection. The increase was reversible since p-eIF2α levels returned to normal levels at 6 h. In the mPFC, notably, a relatively delayed increase in eIF2α phosphorylation occurred as a significant increase in p-eIF2α started at a later time point (1 h). The reason for this slower onset is unclear. It may reflect that additional circuits and transmitters may be involved in processing eIF2α responses to AMPH in this region.

The role of D1Rs and D2Rs in linking AMPH to eIF2α is noteworthy. Both D1R and D2R antagonists blocked the AMPH effect, indicating that both receptors are critical for the event. In the striatum, D1Rs and D2Rs are enriched and are prominently segregated into two phenotypes of medium spiny output neurons, i.e., D1Rs in striatonigral neurons and D2Rs in striatopallidal neurons (Gerfen et al., 1990; Aubert et al., 2000; Bertran-Gonzalez et al., 2010). It is likely that AMPH activates D1Rs to phosphorylate eIF2α in D1R-bearing striatonigral neurons, although this cell type-specific response needs to be proven experimentally. With regard to D2Rs, mechanism(s) underlying their roles are unclear. Presumably, an indirect pathway may enact. D2Rs inhibit local acetylcholine from intrinsic cholinergic interneurons (DeBoer and Abercrombie, 1996; Ding et al., 2000). Blocking D2Rs thus enhances acetylcholine release. Released acetylcholine can activate muscarinic M4 receptors to suppress the eIF2α response to AMPH. M4 receptors are a major subtype of muscarinic receptors expressed in the striatum and are predominantly coexpressed with D1Rs in striatonigral neurons (Ince et al., 1997; Santiago and Potter, 2001). Activation of Gi/o-coupled M4 receptors is known to antagonize Gs-coupled D1Rs in many activity-dependent events, including the AMPH-stimulated immediate early gene expression in the striatum and behavior (Chou et al., 1992; Bernard et al., 1993; Morelli et al., 1993; Wang and McGinty, 1996a; 1996b; 1997). Apparently, a D1R/D2R synergy is implicated in modulating eIF2α, which is consistent with the model that the D1R/D2R synergy mediates dopamine control of direct and indirect pathways and determines basal ganglia outflow and behavior (Onn et al., 2000).

In the mPFC, D1Rs are present in pyramidal spiny output neurons, a major population of neurons in the region (de Almeida et al., 2008; Bergson et al., 1995). Thus, AMPH may activate D1Rs to phosphorylate eIF2α. As to D2Rs, D2R agonists negatively modulate basal and NMDA-mediated increases in acetylcholine release in the prefrontal cortex (Brooks et al., 2007). Therefore, like the striatum, blockade of D2Rs results in more acetylcholine release and activates muscarinic M4 receptors localized on mPFC perikarya (Levey et al., 1991; Volpicelli and Levey, 2004). This in turn likely suppresses the eIF2α response to AMPH. It should be pointed out that AMPH could alter many other neurotransmitters which may be involved in the D2R-dependent regulation of eIF2α.

An important finding in this study is that AMPH stimulated eIF2α phosphorylation. A noticeable feature of AMPH and other stimulants in producing the long-term effect is its dependence on new protein synthesis (Karler et al., 1993; Shimosato and Saito, 1993; Luo et al., 2011; Contreras et al., 2012). However, at present, little is known about the detailed translational program underlying the enduring effect of AMPH. It is thought that stimulants enhance expression of some proteins, while they at the same time inhibit expression of other proteins. This enhanced synthesis of a set of ‘addiction proteins’ together with inhibited synthesis of another set of ‘addiction proteins’ acts jointly to construct the translational program critical for drug addiction. In searching for a regulator at the translational level, eIF2α becomes an attractive target. This factor can be activity-dependently regulated. Its function is characterized by inhibiting general mRNA translation but also initiating the translation of specific mRNAs that contain open reading frames in their 5′ untranslated regions (Dever, 2002; Hinnebusch, 2005; Jackson et al., 2010). Moreover, the eIF2α-mediated inhibition of general translation may reduce the competition of mRNAs for the translational machinery, leading to favoring translation of a selective set of mRNAs presumably associated with AMPH action. In this study, we for the first time observed that eIF2α is regulated by AMPH. While a change in its phosphorylation state does not necessarily mean a functional role, it will be intriguing to investigate whether eIF2α, as a regulatable factor in protein translation, participates in the drug-related protein translation and thereby contributes to synaptic plasticity and drug seeking behavior. Of note, a recent study shows that direct stimulation of eIF2α phosphorylation with an eIF2α phosphatase inhibitor Sal003 induced synaptic plasticity in the form of long-term depression in hippocampal synapses by activating the translation of specific mRNAs rather than by blocking general translation (Di Prisco et al., 2014). Future studies will identify proteins that are down- or upregulated in their synthesis through an eIF2α-dependent translational control in response to AMPH or other stimulants.

Jian et al. (2014) reported that eIF2α was dephosphorylated in the rat basolateral amygdala, which mediated reconsolidation of cocaine memory. A recent study found that a low dose of cocaine (5 mg/kg, i.p.) selectively lowered eIF2α phosphorylation in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of adolescent (5 weeks old) but not adult (3–5 months old) mice, while cocaine at 5 and 10 mg/kg (i.p.) did not alter eIF2α phosphorylation in the nucleus accumbens of adolescent and adult mice, respectively (Huang et al., 2016). The cocaine-induced dephosphorylation of eIF2α is linked to long-term potentiation in VTA dopaminergic neurons and behavior (Huang et al., 2016). Thus, in addition to phosphorylation, dephosphorylation of eIF2α plays a critical role in controlling translational program related to drug memory. It appears that, in an experience-dependent mental disorder such as drug addiction, adaptive changes in eIF2α phosphorylation and function may contribute to the drug-induced synaptic and behavioral plasticity. Moreover, eIF2α may achieve its effects by affecting translation of particular genes rather than general protein translation (Jiang et al., 2010) and may play a role in a brain site-, circuit-, drug-, and disease state-specific manner. In sum, studies on eIF2α-regulated protein synthesis in relation to stimulant action are just emerging. More studies at the translational level are needed in the future to illustrate molecular mechanisms underlying enduring drug seeking behavior.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Animals

We used male Wistar rats weighting 230–330 g (3–4 months old) (Charles River, New York, NY). These animals were individually housed at 23°C and humidity of 50 ± 10% with food and water available ad libitum. The animal room was on a 12/12 h light/dark cycle with lights on at 0700. All animal use procedures were in strict accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

4.2. Systemic drug injection and experimental arrangements

Rats received a single dose of AMPH. The drug was given via an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection at a volume of ~0.5 ml. The dose of AMPH was calculated as the salt. In the first study, rats were injected with AMPH at two different doses (0.5 and 5 mg/kg) and were sacrificed 20 min after drug injection for Western blot analysis of proteins of interest in their responses to AMPH. The two doses of AMPH were chosen based on our previous work in which an i.p. administration of AMPH at 0.69 and 5.53 mg/kg produced litter and considerable behavioral responses in rats, respectively (Wang and McGinty, 1995a). To carry out a time-course study, rats were given a single dose of AMPH (5 mg/kg) and were sacrificed at different time points (1, 3, or 6 h) after AMPH injection. In a pharmacological study defining the role of D1Rs and D2Rs in mediating the effect of AMPH, rats were given an injection of the D1R antagonist SCH23390 (0.5 mg/kg) or D2R antagonist eticlopride (0.5 mg/kg) 20 min prior to an injection of AMPH at 5 mg/kg. Rats were then sacrificed 1 h after AMPH injection. The effectiveness of the two dopamine receptor antagonists following a systemic injection has been well demonstrated in previous behavioral and neurochemical studies (Wang and McGinty, 1995b; 1996a). Age-matched rats were given an injection of saline (~0.5 ml), which served as controls.

4.3. Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was conducted according to our previous work (Mao et al., 2009; Van Dolah et al., 2011). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (65 mg/kg, i.p.) and sacrificed by decapitation. We quickly removed rat brains and cut brains into coronal slices (~1 mm). We then dissected brain regions on coronal slices laid on an ice-cold dissection plate using a 15-gauge blunt tissue punch. The striatum was dissected at the striatal level (0.7–1.7 mm anterior to bregma; Paxinos and Watson, 1997), which contained the caudate putamen and nucleus accumbens (both core and shell subregions). The mPFC was dissected at the level of the mPFC (2.7–3.7 mm anterior to bregma). The dissected mPFC included the anterior cingulate, prelimbic, and infralimbic cortices (Melendez et al., 2004). Brain tissue was lysed in RIPA (radioimmunoprecipitation assay) buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 1 μg/ml leupeptin. Protein concentrations were determined. Samples were stored at −80°C until use. To carry out immunoblots, proteins were separated on SDS NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Separated proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. These membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After primary antibody incubation, membranes were incubated with a secondary antibody (1:2,000). Immunoblots were developed with the enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ). Immunoblots on films were measured using NIH ImageJ gel analysis software. β-Actin was used as a loading control and normalization in Western blot analysis.

4.4. Antibodies and pharmacological agents

Primary antibodies used in this study include rabbit antibodies against phosphorylated eIF2α (p-eIF2α) at serine 51 (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), phosphorylated GluA1 at serine 845 (1:1000, pS845, PhosphoSolutions, Aurora, CO), GluA1 (1:1000, Millipore, Bedford, MA), or β-actin (1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), or a mouse antibody against eIF2α (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology). Pharmacological agents include D-amphetamine sulfate, R(+)-SCH23390 hydrochloride, and S-(−)-eticlopride hydrochloride which were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). AMPH and the two antagonists were dissolved in physiological saline. All agents were freshly prepared at the day of experiments.

4.5. Statistics

Data in this study are presented as means ± SEM and were evaluated using one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), as appropriate, followed by a Bonferroni (Dunn) comparison of groups. Probability levels of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Highlights.

Amphetamine increases eIF2α phosphorylation in the rat striatum.

Amphetamine also increases eIF2α phosphorylation in the prefrontal cortex.

The effect of amphetamine is time-dependent and reversible.

Both dopamine D1 and D2 receptor antagonists block the amphetamine effect.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants DA10355 (J.Q.W.) and MH61469 (J.Q.W.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Aubert I, Ghorayeb I, Normand E, Bloch B. Phenotypical characterization of the neurons expressing the D1 and D2 dopamine receptors in the monkey striatum. J Comp Neurol. 2000;418:22–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergson C, Mrzljak L, Smiley JF, Pappy M, Levenson R, Goldman-Rakic PS. Regional, cellular, and subcellular variations in the distribution of D1 and D5 dopamine receptors in primate brain. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7821–7836. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-07821.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard V, Dumartin B, Lamy E, Bloch B. Fos immunoreactivity after stimulation or inhibition of muscarinic receptors indicates anatomical specificity for cholinergic control of striatal efferent neurons and cortical neurons in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:1218–1225. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertran-Gonzalez J, Herve D, Girault JA, Valjent E. What is the degree of segregation between striatonigral and striatopallidal projections? Front Neuroanat. 2010;4:136. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2010.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JM, Sarter M, Bruno JP. D2-like receptors in nucleus accumbens negatively modulate acetylcholine release in prefrontal cortex. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher SP, Fairbrother IS, Kelly JS, Arbuthnott GW. Amphetamine-induced dopamine release in the rat striatum: an in vivo microdialysis study. J Neurochem. 1988;50:346–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb02919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou H, Ogawa N, Asanuma M, Hirata H, Mori A. Muscarinic cholinergic receptor-mediated modulation on striatal c-fos mRNA expression induced by levodopa in rat brain. J Neural Transm. 1992;90:171–181. doi: 10.1007/BF01250959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras M, Billeke P, Vicencio S, Madrid C, Perdomo G, Gonzalez M, Torrealba F. A role for the insular cortex in long-term memory for context-evoked drug craving in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:2101–2108. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M, Sossin WS, Klann E, Sonenberg N. Translational control of long-lasting synaptic plasticity and memory. Neuron. 2009;61:10–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida J, Palacios JM, Mengod G. Distribution of 5-HT and DA receptors in primate prefrontal cortex: implications for pathophysiology and treatment. Prog Brain Res. 2008;172:101–115. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00905-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBoer P, Abercrombie ED. Physiological release of striatal acetylcholine in vivo: modulation by D1 and D2 dopamine receptor subtypes. J Pharm Exp Ther. 1996;277:775–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dever TE. Gene-specific regulation by general translation factors. Cell. 2002;108:545–556. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00642-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Prisco GV, Huang W, Buffington SA, Hsu CC, Bonnen PE, Placzek AN, Sidrauski C, Krnjevic K, Kaufman R, Walter P, Costa-Mattioli M. Translational control of mGluR-dependent long-term depression and object-place learning by eIF2α. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1073–1082. doi: 10.1038/nn.3754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding YS, Logan J, Bermel R, Garza V, Rice O, Fowler JS, Volkow ND. Dopamine receptor-mediated regulation of striatal cholinergic activity: positron emission tomography studies with norchloro[18F]fluoroepibatidine. J Neurochem. 2000;74:1514–1521. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly N, Gorman AM, Gupta S, Samali A. The eIF2α kinases: their structures and functions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:3493–3511. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1252-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR, Engber TM, Mahan LC, Suswl Z, Chase TN, Monsma FJ, Jr, Sibley DR. D1 and D2 dopamine receptor-regulated gene expression of striatonigral and striatopallidal neurons. Science. 1990;250:1429–1432. doi: 10.1126/science.2147780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM, Moratalla R, Robertson HA. Amphetamine and cocaine induce drug-specific activation of the c-fos gene in striosome-matrix and limbic subdivisions of the striatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6912–6916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakansson K, Galdi S, Hendrick J, Snyder G, Greengard P, Fisone G. Regulation of phosphorylation of the GluR1 AMPA receptor by dopamine D2 receptors. J Neurochem. 2006;96:482–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature. 1999;397:271–274. doi: 10.1038/16729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch AG. Translational regulation of GCN4 and the general amino acid control of yeast. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:407–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.031805.133833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Placzek AN, Viana Di, Prisco G, Khatiwada S, Sidrauski C, Krnjevic K, Walter P, Dani JA, Costa-Mattioli M. Translational control by eIF2α phosphorylation regulates vulnerability to the synaptic and behavioral effects of cocaine. Elife. 2016:e12052. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ince E, Ciliax BJ, Levey AI. Differential expression of D1 and D2 dopamine and m4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor proteins in identified striatonigral neurons. Synapse. 1997;27:357–366. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199712)27:4<357::AID-SYN9>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RJ, Hellen CU, Pestova TV. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:113–127. doi: 10.1038/nrm2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jian M, Luo YX, Xue YX, Han Y, Shi HS, Liu JF, Yan W, Wu P, Meng SQ, Deng JH, Shen HW, Shi J, Lu L. eIF2α dephosphorylation in basolateral amygdala mediates reconsolidation of drug memory. J Neurosci. 2014;34:10010–10021. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0934-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Belforte JE, Lu Y, Yabe Y, Pickel J, Smith CB, Je HS, Lu B, Nakazawa K. eIF2alpha phosphorylation-dependent translation in CA1 pyramidal cells impairs hippocampal memory consolidation without affecting general translation. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2582–2594. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3971-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karler R, Finnegan KT, Calder LD. Blockade of behavioral sensitization to cocaine and amphetamine by inhibitors of protein synthesis. Brain Res. 1993;603:19–24. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klann E, Dever TE. Biochemical mechanisms for translational regulation in synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:931–942. doi: 10.1038/nrn1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and diseases. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey AI, Kitt CA, Simonds WF, Price DL, Brann MR. Identification and localization of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor proteins in brain with subtype-specific antibodies. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3218–3226. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03218.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Jing L, Qin WJ, Zhang M, Lawrence AJ, Chen F, Liang JH. Transcriptional and protein synthesis inhibitors reduce the induction of behavioral sensitization to a single morphine exposure and regulate Hsp70 expression in the mouse nucleus accumbens. Int J Neuropsychopharm. 2011;14:107–121. doi: 10.1017/S146114571000057X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao LM, Wang W, Chu XP, Zhang GC, Liu XY, Yang YJ, Haines M, Papasian CJ, Fibuch EE, Buch S, Chen JG, Wang JQ. Stability of surface NMDA receptors controls synaptic and behavioral adaptations to amphetamine. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:602–610. doi: 10.1038/nn.2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez RI, Gregory ML, Bardo MT, Kalivas PW. Impoverished rearing environment alters metabotropic glutamate receptor expression and function in the prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1980–1987. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClung CA, Nestler EJ. Neuroplasticity mediated by altered gene expression. Neuropsychophamacology. 2008;33:3–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddam B, Roth RH, Bunney BS. Characterization of dopamine release in the rat medial prefrontal cortex as assessed by in vivo microdialysis: comparison to the striatum. Neuroscience. 1990;36:669–676. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90009-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli M, Fenu S, Cozzolino A, Pinna A, Carta A, Di Chiara G. Blockade of muscarinic receptors potentiates D1 dependent turning behavior and c-fos expression in 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats but does not influence D2 mediated response. Neuroscience. 1993;53:673–678. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90615-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Molecular basis of long-term plasticity underlying addition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:119–128. doi: 10.1038/35053570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoa I, Zeng H, Harding HP, Ron D. Feedback inhibition of the unfolded protein response by GADD34-mediated dephosphorylation of eIF2α. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1011–1022. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onn SP, West AR, Grace AA. Dopamine-mediated regulation of striatal neuronal and network interactions. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:S48–56. doi: 10.1016/s1471-1931(00)00020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in sterrotaxic coordinates. Academic; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ruskin DN, Marshall JF. Amphetamine and cocaine-induced Fos in the rat striatum depends on D2 dopamine receptor activation. Synapse. 1994;18:233–240. doi: 10.1002/syn.890180309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago MP, Potter LT. Biotinylated m4-toxin demonstrates more M4 muscarinic receptor protein on direct than indirect striatal projection neurons. Brain Res. 2001;894:12–20. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimosato K, Saito T. Suppressive effect of cycloheximide on behavioral sensitization to methamphetamine in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;234:67–75. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90707-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder GL, Allen PB, Fienberg AA, Valle CG, Huganir RL, Nairn AC, Greenberg P. Regulation of phosphorylation of the GluR1 AMPA receptor in the neostriatum by dopamine and psychostimulants in vivo. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4480–4488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04480.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell. 2009;136:731–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern E, Chinnakkaruppan A, David O, Sonenberg N, Rosenblum K. Blocking the eIF2alpha kinase (PKR) enhances positive and negative forms of cortex-dependent taste memory. J Neurosci. 2013;33:2517–2525. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2322-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh MA, Klann E. Translational control by eIF2α kinases in long-lasting synaptic plasticity and long-term memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2013;105:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dolah DK, Mao LM, Shaffer C, Guo ML, Fibuch EE, Chu XP, Buch S, Wang JQ. Reversible palmitoylation regulates surface stability of AMPA receptors in the nucleus accumbens in response to cocaine in vivo. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:1035–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli LA, Levey AI. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes in cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Prog Brain Res. 2004;145:59–66. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)45003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, McGinty JF. Dose-dependent alteration in zif/268 and preprodynorphin mRNA expression induced by amphetamine or methamphetamine in rat forebrain. J Pharm Exp Ther. 1995a;273:909–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, McGinty JF. Differential effects of D1 and D2 dopamine receptor antagonists on acute amphetamine- or methamphetamine-induced up-regulation of zif/268 mRNA expression in rat forebrain. J Neurochem. 1995b;65:2706–2715. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65062706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, McGinty JF. Scopolamine augments c-fos and zif/268 messenger RNA expression induced by the full D1 dopamine receptor agonist SKF-82958 in the intact rat striatum. Neuroscience. 1996a;72:601–616. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, McGinty JF. Muscarinic receptors regulate striatal neuropeptide gene expression in normal and amphetamine-treated rats. Neuroscience. 1996b;75:43–56. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, McGinty JF. Intrastriatal injection of a muscarinic receptor agonist and antagonist regulates striatal neuropeptide mRNA expression in normal and amphetamine-treated rats. Brain Res. 1997;748:62–70. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wek RC, Jiang HY, Anthony TG. Coping with stress: eIF2 kinases and translational control. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:7–11. doi: 10.1042/BST20060007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]