Abstract

Divorce is a stressor associated with long-term health risk, though the mechanisms of this effect are poorly understood. Cardiovascular reactivity is one biological pathway implicated as a predictor of poor long-term health after divorce. A sample of recently separated and divorced adults (N = 138) was assessed over an average of 7.5 months to explore whether individual differences in heart rate variability—assessed by respiratory sinus arrhythmia—operate in combination with subjective reports of separation-related distress to predict prospective changes in cardiovascular reactivity, as indexed by blood pressure reactivity. Participants with low resting respiratory sinus arrhythmia at baseline showed no association between divorce-related distress and later blood pressure reactivity, whereas participants with high respiratory sinus arrhythmia showed a positive association. In addition, within-person variation in respiratory sinus arrhythmia and between-persons variation in separation-related distress interacted to predict blood pressure reactivity at each laboratory visit. Individual differences in heart rate variability and subjective distress operate together to predict cardiovascular reactivity and may explain some of the long-term health risk associated with divorce.

Keywords: heart rate variability, respiratory sinus arrhythmia, cardiovascular reactivity, divorce, blood pressure reactivity

Divorce is one of life’s most distressing events (Bloom, Asher, & White, 1978) and is tied to increased morbidity (Dahl, Hansen, & Vignes, 2015; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1987) and risk for early death (Shor, Roelfs, Bugyi, & Schwartz, 2012). These effects are well documented (Sbarra, Law, & Portley, 2011) but remain poorly understood (Sbarra, Hasselmo, & Bourassa, 2015). To establish a mechanistic account of how divorce affects health, one must study divorce in relation to biologically plausible pathways that connect to disease-relevant biological responses (cf. Miller, Chen, & Cole, 2009). One potential biological intermediary is cardiovascular reactivity, or change in one’s cardiac physiological state in response to a stressor (Manuck, Kasprowicz, Monroe, Larkin, & Kaplan, 1989). The recruitment of the cardiovascular system during stressful psychological tasks is hypothesized to reflect the mobilization of the sympathetic nervous system in preparation for changes in the metabolic demands of a situation (Sherwood, Allen, Obrist, & Langer, 1986). The ability to respond flexibly to environmental challenge indexes readiness for action in the face of a threat (Porges, 1995), but chronically elevated sympathetic activity can become pathological if maintained over time (Brook & Julius, 2000; Thayer & Lane, 2007).

Cardiovascular Reactivity and Divorce

The cardiovascular-reactivity hypothesis suggests that higher reactivity in response to stress leads to greater risk of developing cardiovascular disease (Treiber et al., 2003). For example, greater cardiovascular reactivity in laboratory stress tasks predicts poorer cardiovascular health and increased risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes (Chida & Steptoe, 2010; Treiber et al., 2003). One way to index cardiovascular reactivity is blood pressure reactivity, which is predictive of left ventricular hypertrophy, anatomic carotid-artery disease, and coronary heart disease (Devereux & Alderman, 1993; Smith & Ruiz, 2002). Higher blood pressure reactivity in response to reminders of divorce may reflect the potential for prolonged wear and tear on the body, ultimately leading to poorer cardiovascular health.

Though the cardiovascular-reactivity hypothesis is well established (Chida & Steptoe, 2010), the majority of this research is cross-sectional. To study how people adjust to a stressful event, researchers should analyze changes in cardiovascular reactivity over time (cf. Steptoe & Kivimäki, 2013). Meta-analyses reveal small but positive associations between increased cardiovascular reactivity in response to laboratory stress and later cardiovascular risk (Chida & Steptoe, 2010; Treiber et al., 2003). Prospective studies demonstrate that the association between low socioeconomic status and heightened cardiovascular reactivity over 4 years predicts the progression of carotid atherosclerosis (Lynch, Everson, Kaplan, Salonen, & Salonen, 1998), though these findings are debated (see Carroll & Smith, 1999). Similarly, men with greater blood pressure reactivity who report high job stress show 46% greater atherosclerotic progression than less reactive men who report lower job stress (Everson et al., 1997). Beyond these studies, longitudinal assessment of cardiovascular reactivity to a psychosocial stressor is rare.

Studies linking separation-related stress to cardiovascular responding generally use data from single-session investigations. For example, adults who reported more divorce-related emotional distress had higher resting blood pressure (Sbarra, Law, Lee, & Mason, 2009). In the same data set, adults who were both higher in attachment anxiety and who spoke about their separation using immersed language also exhibited greater blood pressure reactivity in a subsequent task (Lee, Sbarra, Mason, & Law, 2011). However, these findings have not been extended to longitudinal changes in cardiovascular reactivity.

Heart Rate Variability and Autonomic Flexibility

One predictor of individual differences in cardiovascular reactivity is flexible regulation of the cardiovascular system in response to environmental demands. According to polyvagal theory, the vagus nerve exerts inhibitory control of the myocardium (Porges, 1995). Vagal withdrawal in response to environmental challenge allows the sympathetic nervous system to make bodily resources available for energy expenditure (Porges, 1995). During recovery, balance shifts back toward parasympathetic bodily maintenance and inhibition of the sympathetic response. Heart rate variability reflects fluctuation in the heart’s beat-to-beat interval and is believed to represent, in part, this parasympathetic regulation (Porges, 1995; Thayer, Ahs, Fredrikson, Sollers, & Wager, 2012), also known as cardiac vagal control (Chambers & Allen, 2007). Low heart rate variability at rest is hypothesized to reflect autonomic inflexibility and is linked with depression, anxiety, and decreased cardiovascular health (Beauchaine, 2001; Carney & Freeland, 2009; Dekker et al., 2000). One well-established measure of heart rate variability is respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA; Beauchaine, 2001). RSA is a measure of changes in heart rate during the respiratory cycle, and individual differences in RSA are predictive of emotion-regulatory ability (Beauchaine, 2015).

The Present Study

To address the need for longitudinal studies of cardiovascular reactivity and health-relevant biological intermediaries following marital separation and divorce, we examined blood pressure reactivity in a sample of recently separated and divorced adults (N = 138) assessed at three laboratory visits across an average of 7.5 months. We examined blood pressure reactivity in two ways, first asking whether participants’ separation-related psychological distress and resting RSA at baseline predicted blood pressure reactivity approximately 7.5 months later, then asking how these processes might interact to predict blood pressure reactivity during each of the three laboratory visits. We hypothesized that if higher resting RSA reflects the capacity to effectively regulate physiological responses in potentially stressful situations, then initial separation-related distress and RSA would interact to predict later blood pressure reactivity during a divorce-related mental-activation task (DMAT). We expected that participants who reported the highest levels of separation-related distress and the lowest resting RSA would have the greatest later blood pressure reactivity. Following this initial prospective analysis, we evaluated whether the between-persons and within-person variance components for separation-related distress and RSA might interact to predict blood pressure reactivity at each laboratory visit. We made no a priori hypotheses about whether and how the between-persons and within-person variables might interact at each visit.

Method

Participants

One hundred thirty-eight adults (49 men, 89 women; mean age = 40.65 years, SD = 9.76) who had recently separated from or divorced their partner (mean months since separation = 3.9, SD = 2.4) were recruited from newspaper and LISTSERV advertisements, as well as from a local “divorce recovery” support group. Eligible participants must have physically separated from their partner within the past 5 months, must have cohabited with their former partner for at least 2 years, had to be between the ages of 18 and 65 years, must have never been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, had to report good health, and could not be using blood pressure medications or be pregnant. (Prior studies of blood pressure or separation-related distress were also drawn from this sample; Hasselmo, Sbarra, O’Connor, & Moreno, 2015; Lee et al., 2011; Sbarra et al., 2009.) The average length of participants’ prior relationship was 12.4 years (SD = 8.3). Seventy-eight percent of the sample identified as Caucasian, 14% reported they were Hispanic, 1.5% identified as Asian or African American, 0.8% were Native American, and 4.5% responded with “other.” Approximately 52.2% of the sample reported making less than $30,000 a year.

Of 297 screened participants, 178 were eligible to participate, and 138 completed our first study assessment. Of those 138, the first 29 were recruited for a study with only a single assessment but were included in analyses using full-information maximum-likelihood estimation (see Data Analysis for a more complete description). The remaining 109 participants were recruited for a longitudinal study with assessments at three time points: baseline (Time 1), 3 months after their initial assessment (Time 2), and a follow-up assessment at either 6 or 9 months from the initial assessment (Time 3; participants were randomly assigned to the 6 or 9 month time frame). This sampling procedure was part of a planned missingness design and is discussed in detail elsewhere (see Krietsch, Mason, & Sbarra, 2014). Common reasons for exclusion included having been separated for longer than 5 months (n = 68) and not having cohabited for at least 2 years (n = 24). We report our results here using an average estimate of 7.5 months of prospective assessment.

Of the 109 participants eligible for the follow-up assessments, 90 (82.6%) completed the first two assessments, whereas 79 (72.5%) completed all three assessments. Compared with participants who completed all three assessments, participants who did not complete all assessments had higher self-reported separation-related distress (Cohen’s d = 0.39). In contrast, participants who did not complete the study were not significantly different in terms of age (d = −0.12), sex (d = 0.01), length of prior relationship (d = −0.09), and time since separation (d = −0.14), as well as Time 1 heart rate variability (RSA at rest; d = −0.17), systolic blood pressure (d = 0.18), and diastolic blood pressure (d = 0.12). The University of Arizona Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. All participants signed an informed consent form prior to study participation.

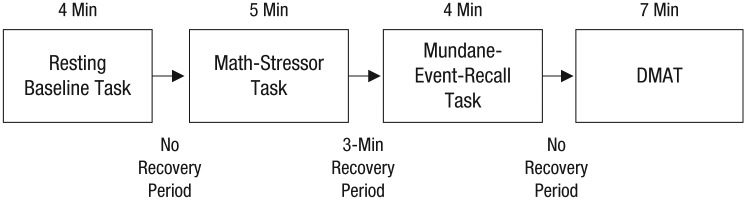

Procedure

Participants were informed that the study’s purpose was to understand “how adults adjust to marital separation and the ways in which your body responds when you reflect on your separation experience.” Prior to their first laboratory visit, participants were mailed a questionnaire packet, which included various self-report measures. They were asked to avoid consuming caffeine and tobacco for at least 4 hr prior to the laboratory visits. In the laboratory, participants completed the series of tasks outlined in Figure 1. Participants were seated in a room that included physiological measurement devices, as well as a speaker and two cameras for communication between the participants and experimenters, who were located in an adjacent room.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of the laboratory procedure participants completed at all three visits. DMAT = divorce-related mental-activation task.

Participants were first asked to sit without speaking and relax while watching a nature video in order to acclimate to the testing room; this task provided baseline measurements. Following the video, participants engaged in a 5-min serial subtraction math-stressor task (see Cacioppo et al., 1995). During the task, participants were asked to pick a number and then, counting aloud, continuously subtract another number from that number. A research assistant probed the participant to go faster during the 3rd, 4th, and 5th min of the serial subtraction task to increase the level of stress.

Following the math-stressor task, participants were given a 3-min recovery period, after which they were asked to recall mundane events (described in more detail in Sbarra and Borelli, 2013). Immediately afterward, participants completed a 7-min DMAT. Participants were asked to “spend some time thinking about yourself and your partner in a variety of situations.” The following series of directions and questions then appeared on a screen, and participants were instructed to “concentrate on . . . any relevant thoughts, feelings, or images [that] come to mind” in response to each one: (a) “Please think about how you and your partner met,” (b) “Whose decision was it to end the relationship?” (c) “When did you first realize you and your partner were headed toward divorce? What was that time like?” (d) “What do you remember about the separation itself, the actual time during which the two of you decided to stop seeing each other?” (e) “How do you think you’ve coped with this separation?” (f) “How much have you seen your partner since the separation? What kind of contact have you had since ending your relationship?” and (g) “What’s been the worst part about this separation for you?” Participants thought about each question for 1 min.

After a 4-min recovery period, the physiological equipment was removed. Sbarra and Borelli (2013), using data from the sample discussed here, provided evidence that the mental-reflection questions in the DMAT are highly similar to what people usually think about when reflecting on their separation and that the content of their separation-related reflections in the laboratory is highly similar to what they think about while at home.

Measures

Self-report measures

Participants reported a variety of demographic information, including age and sex. In addition, they reported on the characteristics of their former relationship, including its length and the amount of time that had passed since their separation. We used the revised version of the Impact of Event Scale (IES-R; Weiss, 2004) to assess the degree to which participants experienced ongoing avoidance, emotional intrusion, and somatic hyperarousal related to a specific stressful event. The scale has 22 questions, and participants rate how much they experience each item using a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 1 = a little bit, 2 = moderately, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = extremely). The IES-R has demonstrated high internal consistency in a range of previous studies and showed high average internal consistency in the current study (α = .93).

Physiological measures

To measure RSA, we collected electrocardiograph data using the Biopac (Santa Barbara, CA) MP100 system and electrocardiograph amplifier. Data were recorded using a standard lead configuration, which included the right clavicle and precordial site V6, with Ag/AgCl electrodes. Signals were recorded on a computer running Biopac AcqKnowledge data-collection software. Heart rate variability analysis software (Version 2.60; MindWare Technologies, Gahanna, OH) was used for postprocessing artifact detection and cleaning of electrocardiograph interbeat-interval signals. RSA was quantified using the natural log of the variance in the residual time series associated with respiration (0.12–0.40 Hz). This method for assessing RSA is a widely used and validated proxy for parasympathetic vagal influences on cardiac chronotropy (Allen, Chambers, & Towers, 2007; Sbarra & Borelli, 2013). In addition to assessing RSA, it is accepted practice to also assess respiration to ensure that variations in RSA across a task are not accounted for by simultaneous changes in respiration (Allen et al., 2007; Denver, Reed, & Porges, 2007). Therefore, we assessed respiration rate using the Biopac respiratory-effort transducer and MindWare heart rate variability analysis software to calculate respiratory rate. Both RSA and respiratory rate were assessed over 1-min epochs across the 4-min baseline task.

Blood pressure was assessed using a noninvasive tonometry device covering the radial artery on the wrist. Research assistants affixed the device to participants’ nondominant arm, which was placed on a table for the duration of the laboratory visit. The tonometry device measures systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure, updating in real time during study tasks (Vasotrac AMP 205; Medwave, Arden Hills, MN). Systolic blood pressure is the peak pressure present in the arteries during the start of the cardiac cycle, whereas diastolic blood pressure is the lowest pressure during the cycle. The Vasotrac system displays arterial pressures using ongoing compression and decompression of the radial artery to detect zero-load states during which pressure signals are measured every 12 to 15 beats. The Vasotrac has excellent convergent validity with other measures of blood pressure, accounting for 95% of the variation in systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure (Belani, Buckley, & Poliac, 1999).

We assessed blood pressure over 1-min epochs during the 5-min math task and 7-min DMAT using blood pressure analysis postprocessing software (MindWare Technologies, Version 2.6). Minute-by-minute values were then averaged to produce mean levels of systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure across the two tasks. We considered extreme blood pressure values (diastolic blood pressure < 40 and > 130; systolic blood pressure < 80 and > 200) as physiologically improbable and removed these values from the analysis. By regressing DMAT blood pressure on math blood pressure, we produced a blood pressure reactivity score that captured reactivity unique to the divorce task when accounting for reactivity to stressful tasks in general. We chose to use blood pressure values during the math-stressor task to create our blood pressure reactivity score, rather than baseline blood pressure, because we were most interested in individual differences in how participants responded to stressful tasks of different types. This approach conceptually matches a capability-model approach to measurement and analysis (see Coan, Allen, & McKnight, 2006) and allows for greater variability in people’s physiological response profiles.

Data analysis

We first used a hierarchical regression framework to evaluate whether RSA at Time 1 moderated the association between Time 1 self-reported separation-related distress and Time 3 blood pressure reactivity during the DMAT. Blood pressure reactivity was calculated by residualizing participants’ blood pressure during the Time 3 math-stressor task from their blood pressure during the DMAT; higher scores reflected an increase in blood pressure reactivity from the math-stressor task to the DMAT at the Time 3 assessment. We also included a measure of respiratory rate during the DMAT at Time 1 to control for participants’ breathing rates when their RSA was measured (Allen et al., 2007; Denver et al., 2007). We evaluated the main effects of IES-R, RSA, respiratory rate, and our focal IES-R × RSA interaction on Time 3 blood pressure reactivity in a restricted model. Next, we included additional covariates of interest (sex, age, month of follow-up visit, time since separation, length of relationship, body mass index, diagnosis of high blood pressure, and self-rated health) to the model to explore whether these might account for the observed effect. We ran both models with systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure independently.

After evaluating initial (Time 1) IES-R scores and RSA as predictors of later blood pressure reactivity, we explored whether within-visit variation in these measures would be associated with blood pressure reactivity using multilevel modeling. Because repeated Level 1 variables included both between-persons and within-person variance, we partitioned the variables of IES-R, RSA, and respiratory rate into their constituent between-persons and within-person components (see Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013), which yielded six total variables, three (Level 2) between-persons variables and three (Level 1) person-centered variables that varied at each laboratory visit. The Level 2 variables represent where participants scored relative to everyone else in the sample, whereas the Level 1 variables represent where participants scored with respect to their own mean across the three laboratory visits. Participants who had only one assessment were coded as missing to account for their lack of measured within-person variability.

As in our initial regression analyses, we specified our multilevel models using blood pressure responses to the DMAT at each laboratory visit as our outcome of interest. We then accounted for the within-visit math-stressor values of blood pressure and linear time (coded 0, 1, and 2 for the three visits), then the between-persons and person-centered versions of IES-R, RSA, and respiratory rate. We also included the interactions of between-persons and person-centered variation in IES-R and RSA as predictors of blood pressure reactivity. We expected to replicate the IES-R × RSA interaction found in our first set of analyses, but we made no a priori hypotheses about the nature of this interaction; instead, we explored all four possible combinations of the two-way interaction predicting blood pressure reactivity (i.e., between-participants IES-R interacting with between-persons RSA, between-persons IES-R interacting with person-centered RSA, person-centered IES-R interacting with person-centered RSA, and person-centered IES-R interacting with between-persons RSA). Finally, we added additional covariates of interest (sex, age, month of follow-up visit, time since separation, length of relationship, body mass index, diagnosis of high blood pressure, and self-rated health) to both models to explore whether these might account for the observed effects. We ran models for systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure independently.

Of the original sample of 134, only 79 participants had full data at Time 3. To account for issues with missingness, we used full-information maximum-likelihood estimation in our regression and maximum-likelihood estimation in our multilevel regression analyses. Because of possible issues with multicollinearity, we mean-centered both IES-R and RSA at Time 1 and used the robust maximum-likelihood estimation in Mplus (Version 7.11; Muthén & Muthén, 2012) in our regression analyses. We ran the multilevel models using the mixed-analysis function in SPSS Version 23. In both cases, we decomposed interactions using Preacher, Curran, and Bauer’s (2006) utility for probing interactions from multiple regression and multilevel models. Finally, we conducted additional post hoc analyses examining whether extreme scores might have biased our model estimates. The results of these additional analyses are reported in the Supplemental Material available online.

Results

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics and a correlation matrix of the main variables included in the study.

Table 1.

Demographic Statistics for and Correlations Between Primary Study Variables

| Correlations |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 1. Time 1 IES-R | 31.65 | 16.43 | — | ||||||||

| 2. Time 1 RSA | 5.91 | 1.25 | .07 | — | |||||||

| 3. Time 1 respiratory rate | 12.05 | 3.69 | −.09 | −.11 | — | ||||||

| 4. Time 3 DMAT systolic blood pressure | 141.71 | 19.32 | .23 | −.43 | −.03 | — | |||||

| 5. Time 3 math systolic blood pressure | 142.43 | 20.26 | .10 | −.40 | −.05 | .81 | — | ||||

| 6. Time 3 DMAT diastolic blood pressure | 81.53 | 14.07 | .18 | −.33 | −.00 | .92 | .75 | — | |||

| 7. Time 3 math diastolic blood pressure | 82.53 | 13.83 | .04 | −.35 | −.01 | .73 | .95 | .78 | — | ||

| 8. Age | 40.65 | 9.71 | .01 | −.35 | −.14 | .34 | .23 | .18 | .12 | — | |

| 9. Sex | — | — | −.01 | .06 | −.06 | .12 | .16 | .18 | .18 | −.00 | — |

| 10. Relationship length | 163.09 | 99.83 | −.03 | −.21 | .03 | .40 | .16 | .22 | .06 | .62 | .05 |

Note: For all values, we used the full-information maximum-likelihood procedure to estimate missing data. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) and respiratory rate were measured during a resting baseline assessment task. Relationship length was assessed in months; age was assessed in years. DMAT = divorce-related mental-activation task, IES-R = revised version of the Impact of Event Scale (Weiss, 2004).

Prospective prediction of blood pressure reactivity

Our first model predicted Time 3 systolic blood pressure during the DMAT. This model included three focal predictors (Time 1 IES-R score, Time 1 RSA, and their interaction), Time 1 DMAT blood pressure values, and two control variables (Time 1 respiratory rate, Time 3 math blood pressure). The analyses revealed significant main effects of IES-R score, b = 0.25, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [0.09, 0.41], p = .003, but not RSA, b = −1.87, 95% CI = [−5.10, 1.35], p = .257. In addition, the IES-R Score × RSA interaction was a significant predictor, b = −0.18, 95% CI = [–0.32, –0.01], p = .012. The effects of the focal predictors, Time 1 IES-R score (β = 0.22), Time 1 RSA (β = −0.12), and their interaction (β = 0.14), were moderate in size. We then included covariates of interest (sex, age, month of follow-up visit, time since separation, and length of relationship) in the model. In addition, we included body mass index, diagnosis of high blood pressure, and self-reported physical health as blood-pressure-relevant covariates to ensure our effects were not due to health-status variables (see Sbarra et al., 2009). All substantive results were replicated when we included these covariates.

We next specified our model predicting Time 3 DMAT diastolic blood pressure. The analyses again revealed significant main effects of Time 1 IES-R score, b = 0.19, 95% CI = [0.10, 0.28], p < .001, and Time 1 RSA, b = −1.38, 95% CI = [−4.02, 1.26], p = .004. In addition, the focal IES-R Score × RSA interaction was a significant predictor, b = 0.10, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.17], p = .001. The effects of the focal predictors, Time 1 IES-R score (β = 0.21), Time 1 RSA (β = −0.12), and their interaction (β = 0.17), were again moderate in size. We then included covariates of interest in the model. All substantive results were replicated when we included these covariates. The results of both models predicting systolic and diastolic blood pressure are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results From Hierarchical Regression Models Predicting Blood Pressure Reactivity During the Divorce-Related Mental-Activation Task (DMAT)

| Model 1 (without

covariates) |

Model 2 (with

covariates) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | |

| Outcome: systolic blood pressure | |||||

| Intercept | 17.55 | [–15.04, 50.13] | 36.33* | [0.17, 72.49] | |

| Time 1 DMAT blood pressure | 0.15* | [0.02, 0.31] | 0.09 | [–0.10, 0.28] | |

| Time 3 math blood pressure | 0.70** | [0.49, 0.92] | 0.68** | [0.49, 0.87] | |

| Time 1 respiratory rate | 0.26 | [–0.40, 0.91] | 0.15 | [–0.53, 0.82] | |

| Time 1 RSA | −1.87 | [–5.10, 1.35] | −1.90 | [–5.57, 1.78] | |

| Time 1 IES-R | 0.25** | [0.09, 0.41] | 0.20** | [0.05, 0.35] | |

| Time 1 RSA × Time 1 IES-R | 0.18* | [0.04, 0.31] | 0.14* | [0.03, 0.24] | |

| Sex | — | — | 0.67 | [–1.98, 3.32] | |

| Age | — | — | −0.34 | [–0.81, 0.13] | |

| Time since separation | — | — | −0.14 | [–1.47, 1.92] | |

| Relationship length | — | — | 0.07** | [0.03, 0.11] | |

| Time 3 group | — | — | −3.63 | [–8.63, 1.37] | |

| Body mass index | — | — | 0.27 | [–0.10, 0.64] | |

| Hypertension self-diagnosis | — | — | 6.49 | [–2.50, 15.57] | |

| Self-reported health | — | — | −1.01 | [–3.70, 1.69] | |

|

| |||||

| Outcome: diastolic blood pressure | |||||

| Intercept | 9.85 | [–3.33, 23.04] | 20.37 | [–6.21, 49.94] | |

| Time 1 DMAT blood pressure | 0.05 | [–0.13, 0.23] | 0.05 | [–0.16, 0.26] | |

| Time 3 math blood pressure | 0.79** | [0.60, 0.98] | 0.75** | [0.09, 0.98] | |

| Time 1 respiratory rate | 0.18 | [–0.29, 0.64] | 0.15 | [–0.36, 0.67] | |

| Time 1 RSA | −1.34 | [–4.02, 1.26] | −2.11 | [–6.22, 2.00] | |

| Time 1 IES-R | 0.19** | [0.10, 0.28] | 0.19** | [0.09, 0.29] | |

| Time 1 RSA × Time 1 IES-R | 0.11** | [0.04, 0.17] | 0.11* | [0.03, 0.20] | |

| Sex | — | — | 0.53 | [–1.74, 2.81] | |

| Age | — | — | −0.12 | [–0.50, 0.27] | |

| Time since separation | — | — | 0.21 | [–0.94, 1.36] | |

| Relationship length | — | — | 0.01 | [–0.02, 0.04] | |

| Time 3 group | — | — | −3.88 | [–8.98, 1.36] | |

| Body mass index | — | — | 0.12 | [–0.18, 0.42] | |

| Hypertension self-diagnosis | — | — | 0.20 | [–6.38, 6.77] | |

| Self-reported health | — | — | −0.43 | [–2.58, 1.73] | |

Note: Time 3 group refers to whether participants completed the Time 3 laboratory visit 6 or 9 months after the Time 1 visit. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) and respiratory rate were measured during a resting baseline assessment task. Relationship length was assessed in months; age was assessed in years. CI = confidence interval, IES-R = revised version of the Impact of Event Scale (Weiss, 2004).

p < .05. **p < .01.

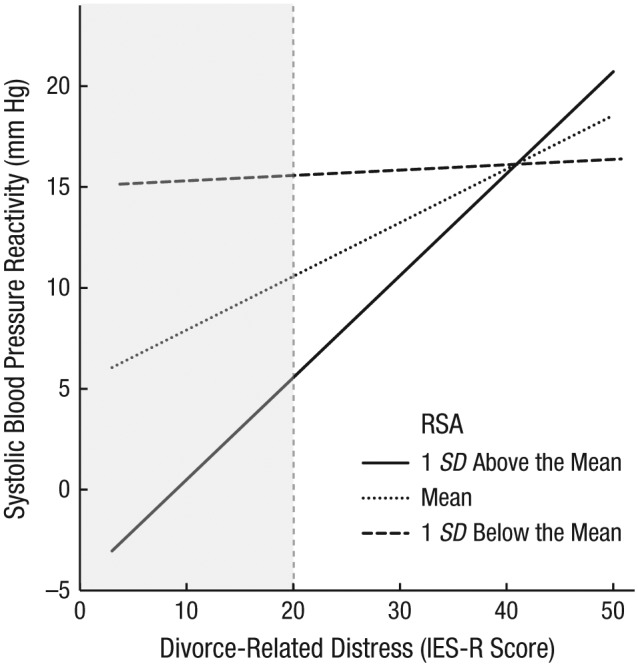

We deconstructed the interaction of IES-R score and RSA at Time 1 as a predictor of Time 3 systolic blood pressure (see Fig. 2). The association of IES-R and systolic blood pressure was significant and positive at the mean level of RSA, b = 0.25, 95% CI = [0.09, 0.42], p = .003, and at 1 standard deviation above the mean for RSA, b = 0.48, 95% CI = [0.27, 0.69], p < .001. In contrast, associations between IES-R scores and systolic blood pressure reactivity were not significant for participants with an RSA level 1 standard deviation below the mean, b = 0.03, 95% CI = [−0.24, 0.29], p = .851. The simple slope became significant at RSA levels above 5.55. Finally, participants’ systolic blood pressure reactivity differed significantly depending on their RSA levels when IES-R scores ranged from 0 to 19.99 but did not significantly differ at IES-R scores above 20. In short, people with lower RSA had higher blood pressure reactivity regardless of their IES-R scores, but as people’s RSA level increased, relatively higher IES-R scores predicted greater blood pressure reactivity at Time 3. These substantive effects were replicated for diastolic blood pressure.

Fig. 2.

Interaction of divorce-related distress score and respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) at Time 1 on systolic blood pressure reactivity at Time 3 (~7.5 months later). Participants’ mean score on the revised version of the Impact of Event Scale (IES-R; Weiss, 2004) indexed their divorce-related distress. Systolic blood pressure reactivity at Time 3 was assessed during a divorce-related mental-activation task (DMAT), controlling for blood pressure during a prior math-stressor task. The effects of three covariates (Time 3 blood pressure during the math-stressor task, Time 1 blood pressure and respiratory rate during the DMAT) were removed from values on the y-axis. The shaded area shows the range of IES-R scores at which systolic blood pressure reactivity differed significantly by RSA levels.

Multilevel analyses: within-visit prediction of blood pressure reactivity

Our multilevel models, which included all available measurements of RSA (including respiratory rate as a control variable), IES-R, and blood pressure over the three time points of the study, revealed significant main effects of between-persons IES-R scores, b = 0.15, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.29], p = .031, between-persons RSA, b = −1.71, 95% CI = [−3.13, −0.29], p = .018, and person-centered RSA, b = −2.08, 95% CI = [−3.87, −0.29], p = .023, as predictors of systolic blood pressure reactivity. In addition, the interaction of between-persons IES-R and person-centered RSA significantly predicted systolic blood pressure reactivity, b = −0.16, 95% CI = [−0.32, −0.01], p = .038. None of the other three combinations of between-persons and person-centered IES-R scores and RSA significantly predicted systolic blood pressure reactivity. We then included sex, age, month of follow-up visit, time since separation, length of relationship, body mass index, diagnosis of high blood pressure, and self-rated health as Level 2 time-invariant covariates. The substantive results of the IES-R Score × RSA interaction and between-persons IES-R score held when including these covariates, though both main effects of RSA were no longer significant.

The multilevel models predicting diastolic blood pressure revealed significant main effects of between-persons IES-R scores, b = 0.13, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.22], p = .007, and between-persons RSA, b = −1.21, 95% CI = [−2.15, −0.28], p = .011. In addition, the interaction of between-persons IES-R scores and person-centered RSA predicted diastolic blood pressure reactivity, b = −0.10, 95% CI = [−0.21, 0.00], p = .060, though not at or below the .05 level of significance. None of the other three interaction terms of between-persons and person-centered IES-R scores and RSA predicted diastolic blood pressure reactivity. When we included the Level 2 covariates in the model, between-persons IES-R scores continued to predict diastolic blood pressure, but between-persons RSA no longer did. In this model, the interaction of between-persons IES-R scores and person-centered RSA was stronger, b = −0.12, 95% CI = [−0.22, −0.02], p = .020, than in the model without covariates. The full results of the models predicting systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure, both with and without covariates, are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results From Multilevel Models Predicting Blood Pressure Reactivity During the Divorce-Related Mental-Activation Task (DMAT)

| Level 1 (without

covariates) |

Level 2 (with

covariates) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | b | 95% CI | b | 95% CI | |

| Outcome: systolic blood pressure | |||||

| Intercept | 37.29** | [24.50, 50.07] | 33.82** | [12.89, 54.77] | |

| Time | 1.20 | [–1.07, 3.47] | 1.43 | [–0.77, 3.63] | |

| Math systolic blood pressure | 0.71** | [0.62, 0.79] | 0.72** | [0.63, 0.82] | |

| Between-persons IES-R | 0.15* | [0.01, 0.29] | 0.17* | [0.03, 0.31] | |

| Within-person IES-R | 0.01 | [–0.16, 0.18] | −0.03 | [–0.19, 0.14] | |

| Between-persons RSA | −1.71* | [–3.13, –0.29] | −0.63 | [–2.36, 1.10] | |

| Within-person RSA | −2.08* | [–3.87, –0.29] | −1.38 | [–3.08, 0.31] | |

| Between-persons respiratory rate | 0.18 | [–0.26, 0.61] | 0.28 | [–0.18, 0.75] | |

| Within-person respiratory rate | 0.37 | [–0.30, 1.04] | 0.46 | [–0.15, 1.08] | |

| Within-Person IES-R × Within-Person RSA | 0.05 | [–0.14, 0.24] | 0.02 | [–0.15, 0.19] | |

| Within-Person IES-R × Between-Persons RSA | −0.04 | [–0.16, 0.09] | −0.05 | [–0.18, 0.07] | |

| Between-Persons IES-R × Between-Persons RSA | −0.05 | [–0.16, 0.06] | −0.03 | [–0.14, 0.07] | |

| Between-Persons IES-R × Within-Person RSA | −0.16* | [–0.32, –0.01] | −0.20** | [–0.34, –0.05] | |

| Sex | — | — | −0.65 | [–2.45, 1.15] | |

| Age | — | — | 0.17 | [–0.08, 0.43] | |

| Time since separation | — | — | −0.97 | [–1.95, 0.01] | |

| Relationship length | — | — | 0.02 | [–0.00, 0.05] | |

| Time 3 group | — | — | 0.17 | [–2.06, 1.13] | |

| Body mass index | — | — | 0.27 | [–0.03, 0.57] | |

| Hypertension self-diagnosis | — | — | 1.00 | [–4.47, 6.46] | |

| Self-reported health | — | — | −0.56 | [–2.87, 1.76] | |

|

| |||||

| Outcome: diastolic blood pressure | |||||

| Intercept | 18.01** | [10.58, 25.45] | 14.25* | [0.58, 27.92] | |

| Time | 1.60 | [–0.02, 3.22] | 1.52 | [–0.05, 3.10] | |

| Math diastolic blood pressure | 0.73** | [0.64, 0.81] | 0.75** | [0.65, 0.85] | |

| Between-persons IES-R | 0.13** | [0.04, 0.22] | 0.14* | [0.04, 0.23] | |

| Within-person IES-R | 0.11 | [–0.00, 0.23] | 0.08 | [–0.03, 0.20] | |

| Between-persons RSA | −1.22* | [–2.15, –0.28] | −0.97 | [–2.20, 0.25] | |

| Within-person RSA | −0.91* | [–2.15, 0.32] | −0.48 | [–1.67, 0.72] | |

| Between-persons respiratory rate | 0.09 | [–0.19, 0.37] | 0.19 | [–0.14, 0.51] | |

| Within-person respiratory rate | 0.18 | [–0.29, 0.66] | 0.23 | [–0.21, 0.67] | |

| Within-Person IES-R × Within-Person RSA | 0.03 | [–0.09, 0.16] | 0.01 | [–0.11, 0.13] | |

| Within-Person IES-R × Between-Persons RSA | −0.02 | [–0.11, 0.07] | −0.06 | [–0.15, 0.03] | |

| Between-Persons IES-R × Between-Persons RSA | −0.05 | [–0.12, 0.03] | −0.04 | [–0.12, 0.03] | |

| Between-Persons IES-R × Within-Person RSA | −0.10 | [–0.21, 0.00] | −0.12* | [–0.22, –0.02] | |

| Sex | — | — | −0.17 | [–1.42, 1.08] | |

| Age | — | — | 0.09 | [–0.09, 0.27] | |

| Time since separation | — | — | −0.52 | [–1.20, 0.17] | |

| Relationship length | — | — | 0.00 | [–0.01, 0.02] | |

| Time 3 group | — | — | −0.22 | [–1.33, 0.89] | |

| Body mass index | — | — | 0.17 | [–0.04, 0.38] | |

| Hypertension self-diagnosis | — | — | 1.13 | [–2.63, 4.90] | |

| Self-reported health | — | — | −0.10 | [–1.71, 1.52] | |

Note: Time 3 group refers to whether participants completed the Time 3 laboratory visit 6 or 9 months after the Time 1 visit. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) and respiratory rate were measured during a resting baseline assessment task. Relationship length was assessed in months; age was assessed in years. CI = confidence interval, IES-R = revised version of the Impact of Event Scale (Weiss, 2004).

p < .05. **p < .01.

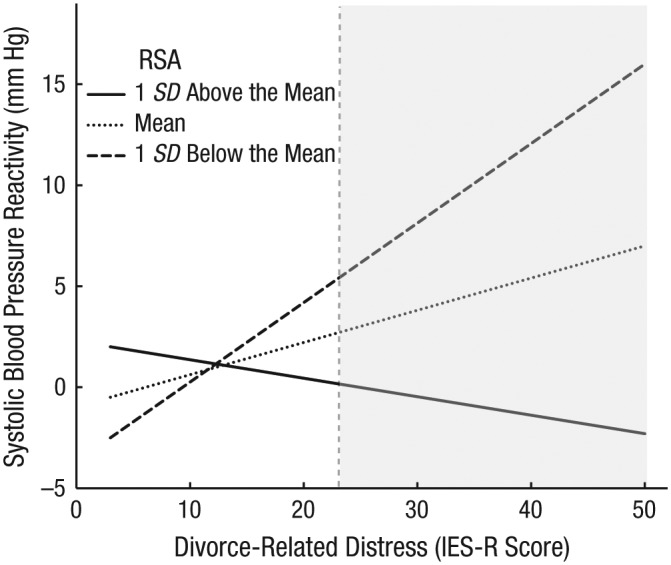

We deconstructed the cross-level interaction of between-persons IES-R scores and person-centered RSA as a predictor of systolic blood pressure reactivity; the simple slopes for this analysis are displayed in Figure 3. There was no significant effect of time in the models (i.e., no significant linear trend across laboratory visits), and as a result, the interaction effect visualized in Figure 3 was estimated to be equivalent at each time point. The simple slopes revealed that the association of between-persons IES-R scores and systolic blood pressure reactivity was significant and positive at the mean levels of person-centered RSA, b = 0.15, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.20], p = .031, and 1 standard deviation below participants’ own mean for RSA, b = 0.48, 95% CI = [0.14, 0.52], p < .001. In contrast, participants with RSA levels 1 standard deviation above the mean showed weaker associations between IES-R scores and systolic blood pressure reactivity, b = −0.17, 95% CI = [−0.52, 0.15], p = .315. These substantive effects were replicated for diastolic blood pressure. These findings suggest that, in addition to a relatively large between-persons effect for self-reported distress on blood pressure reactivity, when participants’ resting RSA is at their individual mean level or 1 standard deviation below their own mean, participants with greater separation-related distress have relatively higher blood pressure reactivity. In other words, mean to low person-centered RSA potentiated the association between subjective distress and blood pressure reactivity at each laboratory visit. When people had higher RSA compared with their own mean RSA, the association between separation-related distress and blood pressure reactivity was attenuated.

Fig. 3.

Interaction of between-persons divorce-related distress score and person-centered respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) on systolic blood pressure reactivity. Divorce-related distress was indexed by participants’ mean score on the revised version of the Impact of Event Scale (IES-R; Weiss, 2004). Systolic blood pressure reactivity was assessed during a divorce-related mental-activation task, controlling for blood pressure during a prior math-stressor task. The effect of the intercept was removed from the values on the y-axis. The shaded area shows the range of IES-R scores at which systolic blood pressure reactivity differed significantly by RSA levels.

Discussion

In a sample of recently separated and divorced adults, we examined the interaction of separation-related psychological distress and RSA as a predictor of blood pressure reactivity in two ways: first using baseline data to predict blood pressure reactivity an average of 7.5 months later, and then within each of the three laboratory visits across this same period of time.

In the first set of prospective analyses, higher initial levels of separation-related distress predicted greater blood pressure reactivity during the DMAT approximately 7.5 months later. The interaction between IES-R scores and RSA also revealed a significant association with later blood pressure reactivity. In one respect, our hypothesis was confirmed: Participants reporting both high separation-related distress with low RSA at rest had high levels of blood pressure reactivity during the DMAT 7.5 months later. The results presented a more complex picture, however, with low RSA predicting high blood pressure reactivity regardless of participants’ separation-related distress.1 As RSA increased, there was an increasingly positive association between subjective distress and later blood pressure reactivity, which suggests that the lowest levels of blood pressure reactivity were observed among people with low subjective distress and high RSA at rest. This interaction can also be interpreted in the opposite direction: RSA was associated with blood pressure reactivity only at lower levels of self-reported separation distress. These results suggest that both low levels of separation-related distress and relatively high RSA buffer against blood pressure reactivity following divorce, whereas people with low RSA show an exaggerated blood pressure reactivity profile 7.5 months later. The size of this effect was such that a 1-standard-deviation increase in a participant’s separation-related distress translated to a difference of 7.9 mm mercury (mm Hg) of systolic blood pressure for people with relatively high RSA.

In our second set of analyses, we explored the association between separation-related distress, RSA, and blood pressure reactivity at each of the three laboratory visits. Participants who reported higher overall separation-related distress had higher blood pressure reactivity across the entire study period (i.e., at each visit). In addition, this between-persons difference interacted with person-centered RSA at each visit. When participants were at or below their own resting RSA levels across the entire study, separation-related distress was positively correlated with blood pressure reactivity. At each visit, participants who reported high separation-related distress and who had low levels of person-centered RSA had the highest overall levels of blood pressure reactivity. When participants’ RSA was 1 standard deviation above their own average resting RSA, however, the association between separation-related distress and blood pressure reactivity was attenuated. One way to interpret this pattern of association is that when people’s general cardiac vagal capacity is diminished, the association between their separation-related distress and blood pressure reactivity is potentiated.

As one of the first prospective studies to explore blood pressure reactivity longitudinally and following marital separation specifically, this research has clear theoretical and clinical implications. First, the findings illuminate one pathophysiological route through which divorce-related psychological distress may affect long-term health. Although the effects of divorce on health are well-established (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1987; Sbarra et al., 2011), the biologically plausible pathways that transmit this risk remain poorly understood (Sbarra et al., 2015). Our findings suggest that cardiovascular reactivity is a pathway through which divorce may transmit health risk, particularly for people with high levels of psychological distress. Participants with greater divorce-related distress continued to demonstrate heightened blood pressure reactivity an average of 7.5 months later.

These results are notable for two reasons. First, they distinguish between blood pressure reactivity during a general stressor and during a divorce-related stressor, as the primary results emerged from models that included a math-stressor task as a covariate. Second, this study is one of the first investigations of person-centered variation in RSA and its relation to blood pressure reactivity. The results suggest that variation in people’s own RSA over time predict differences in blood pressure reactivity. Future investigations into RSA should acknowledge and explore meaningful ways in which RSA might vary from visit to visit and how deviations from a person’s own mean RSA level can predict health-relevant biological outcomes.

In addition, the size of the study effects may be clinically meaningful. People with high RSA had a difference of 7.9 mm Hg systolic blood pressure per standard-deviation change in divorce-specific-distress scores, and the reactivity of participants with low RSA best matched that of participants at the highest levels of distress. An increase in 20 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure is associated with a doubling of the risk for mortality as a result of cardiovascular causes (Prospective Studies Collaboration, 2002), so this difference—if maintained over the long term—would translate to an increase of between 20% and 25% in mortality from a cardiovascular event. Although it is unlikely that recently separated or divorced people would show this large a difference in blood pressure consistently over time and a 7.9 mm Hg increase in blood pressure may affect people differently across the range of possible blood pressure values, frequent ongoing reminders of people’s separation could result in increased risk for cardiovascular pathology as a result of cardiovascular reactivity.

The study’s results should be understood in light of its limitations. First, the study had a moderate level of dropout (27.5%) over the three laboratory visits. Added to this was the inclusion of 29 participants originally recruited before the longitudinal design was implemented, which resulted in only 79 participants who completed all study assessments (57%). Although we used full-information maximum-likelihood estimation to account for missing data, it is possible that differential attrition may have biased the study’s results. Second, although this research was one of the first longitudinal studies of cardiovascular reactivity after a stressful event, we have no assessments of preclinical disease states (e.g., Smith et al., 2011); longer-term studies are needed to link these disease-relevant outcomes to separation-related distress through cardiovascular reactivity. Nevertheless, the study of blood pressure reactivity has clear end-point health relevance (Chida & Steptoe, 2010; Treiber et al., 2003).

Conclusion

In this study, recently separated and divorced adults’ initial separation-related psychological distress and RSA interacted to predict their blood pressure reactivity 7.5 months later. In addition, person-centered RSA interacted with differences in between-persons separation-related distress to predict blood pressure reactivity at each laboratory visit. At all laboratory visits, participants who had resting RSA at or below their own RSA mean (across all laboratory visits) demonstrated a significant positive association between separation-related distress and blood pressure reactivity, which suggests that person-centered differences in RSA may reflect diminished autonomic flexibility (cf. Thayer & Lane, 2007). Taken together, these results suggest that blood pressure reactivity is one biologically plausible mechanism that may link marital separation to distal health outcomes. Importantly, this risk depends on individual differences in RSA and participants’ distress regarding the separation experience.

Supplementary Material

We also note that there was not a main effect of RSA predicting blood pressure reactivity when we excluded the interaction term from our models. This is described in more detail in the Supplemental Material available online.

Footnotes

Action Editor: Wendy Berry Mendes served as action editor for this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

Funding: D. A. Sbarra’s work on this article was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD069498), and the overall project was funded by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH074637) and the National Institute on Aging (AG028454 and AG036895).

Supplemental Material: Additional supporting information can be found at http://pss.sagepub.com/content/by/supplemental-data

References

- Allen J. J. B., Chambers A. S., Towers D. N. (2007). The many metrics of cardiac chronotropy: A pragmatic primer and a brief comparison of metrics. Biological Psychology, 74, 243–262. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine T. (2001). Vagal tone, development, and Gray’s motivational theory: Toward an integrated model of autonomic nervous system functioning in psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 13, 183–214. doi: 10.1017/S0954579401002012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine T. P. (2015). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia: A transdiagnostic biomarker of emotion dysregulation and psychopathology. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belani K. G., Buckley J. J., Poliac M. O. (1999). Accuracy of radial artery blood pressure determination with the Vasotrac™. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia, 46, 488–496. doi: 10.1007/bf03012951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom B. L., Asher S. J., White S. W. (1978). Marital disruption as a stressor: A review and analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 85, 867–894. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.85.4.867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N., Laurenceau J.-P. (2013). Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brook R. D., Julius S. (2000). Autonomic imbalance, hypertension, and cardiovascular risk. American Journal of Hypertension, 13(6, Pt. 2), 112S–122S. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(00)00228-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J. T., Malarkey W. B., Kiecolt-Glaser J. K., Uchino B. N., Sgoutasemch S. A., Sheridan J. F., . . . Glaser R. (1995). Heterogeneity in neuroendocrine and immune responses to brief psychological stressors as a function of autonomic cardiac activation. Psychosomatic Medicine, 57, 154–164. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199503000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney R. M., Freeland K. E. (2009). Depression and heart rate variability in patients with coronary heart disease. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 76(Suppl. 2), S13–S17. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.76.s2.03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll D., Smith G. D. (1999). Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular response. American Journal of Public Health, 89, 415–416. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.3.415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers A. S., Allen J. J. B. (2007). Cardiac vagal control, emotion, psychopathology, and health. Biological Psychology, 74, 113–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chida Y., Steptoe A. (2010). Greater cardiovascular responses to laboratory mental stress are associated with poor subsequent cardiovascular risk status: A meta-analysis of prospective evidence. Hypertension, 55, 1026–1032. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.146621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coan J. A., Allen J. J. B., McKnight P. E. (2006). A capability model of individual differences in frontal EEG asymmetry. Biological Psychology, 72, 198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl S.-Å., Hansen H.-T., Vignes B. (2015). His, her, or their divorce? Marital dissolution and sickness absence in Norway. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 461–479. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J. M., Crow R. S., Folsom A. R., Hannan P. J., Liao D., Swenne C. A., Schouten E. G. (2000). Low heart rate variability in a 2-minute rhythm strip predicts risk of coronary heart disease and mortality from several causes: The ARIC study. Circulation, 102, 1239–1244. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.102.11.1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denver J. W., Reed S. F., Porges S. W. (2007). Methodological issues in the quantification of respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Biological Psychology, 74, 286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devereux R. B., Alderman M. H. (1993). Role of preclinical cardiovascular disease in the evolution from risk factor exposure to development of morbid events. Circulation, 88(4, Pt. 1), 1444–1455. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.4.1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson S. A., Lynch J. W., Chesney M. A., Kaplan G. A., Goldberg D. E., Shade S. B., . . . Salonen J. T. (1997). Interaction of workplace demands and cardiovascular reactivity in progression of carotid atherosclerosis: Population based study. BMJ, 314, Article 553. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7080.553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo K., Sbarra D. A., O’Connor M.-F., Moreno F. A. (2015). Psychological distress following marital separation interacts with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene to predict cardiac vagal control in the laboratory. Psychophysiology, 52, 736–744. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser J. K., Fisher L. D., Ogrocki P., Stout J. C., Speicher C. E., Glaser R. (1987). Marital quality, marital disruption, and immune function. Psychosomatic Medicine, 49, 13–34. doi: 10.1111/j.0197-6664.2004.00055.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krietsch K. N., Mason A. E., Sbarra D. A. (2014). Sleep complaints predict increases in resting blood pressure following marital separation. Health Psychology, 33, 1204–1213. doi: 10.1037/hea0000089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L. A., Sbarra D. A., Mason A. E., Law R. W. (2011). Attachment anxiety, verbal immediacy, and blood pressure: Results from a laboratory-analogue study following marital separation. Personal Relationships, 18, 285–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2011.01360.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J. W., Everson S. A., Kaplan G. A., Salonen R., Salonen J. T. (1998). Does low socioeconomic status potentiate the effects of heightened cardiovascular responses to stress on the progression of carotid atherosclerosis? American Journal of Public Health, 88, 389–394. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.88.3.389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuck S. B., Kasprowicz A. L., Monroe S. M., Larkin K. T., Kaplan J. R. (1989). Psychophysiologic reactivity as a dimension of individual differences. In Schneiderman N., Weiss S. M., Kaufmann P. G. (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in cardiovascular behavioral medicine (pp. 365–382). New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-0906-0_23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. E., Chen E., Cole S. W. (2009). Health psychology: Developing biologically plausible models linking the social world and physical health. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 501–524. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén K., Muthén O. (2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Porges S. W. (1995). Cardiac vagal tone: A physiological index of stress. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 19, 225–233. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)00066-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K. J., Curran P. J., Bauer D. J. (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31, 437–448. doi: 10.3102/10769986031004437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prospective Studies Collaboration. (2002). Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: A meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. The Lancet, 360, 1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbarra D. A., Borelli J. L. (2013). Heart rate variability moderates the association between attachment avoidance and self-concept reorganization following marital separation. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 88, 253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbarra D. A., Hasselmo K., Bourassa K. J. (2015). Divorce and health: Beyond individual differences. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24, 109–113. doi: 10.1177/0963721414559125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbarra D. A., Law R. W., Lee L. A., Mason A. E. (2009). Marital dissolution and blood pressure reactivity: Evidence for the specificity of emotional intrusion-hyperarousal and task-rated emotional difficulty. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71, 532–540. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181a23eee [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbarra D. A., Law R. W., Portley R. M. (2011). Divorce and death: A meta-analysis and research agenda for clinical, social, and health psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 454–474. doi: 10.1177/1745691611414724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood A., Allen M. T., Obrist P. A., Langer A. W. (1986). Evaluation of beta-adrenergic influences on cardiovascular and metabolic adjustments to physical and psychological stress. Psychophysiology, 23, 89–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shor E., Roelfs D. J., Bugyi P., Schwartz J. E. (2012). Meta-analysis of marital dissolution and mortality: Reevaluating the intersection of gender and age. Social Science & Medicine, 75, 46–59. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. W., Ruiz J. M. (2002). Psychosocial influences on the development and course of coronary heart disease: Current status and implications for research and practice. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 548–568. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.3.548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. W., Uchino B. N., Florsheim P., Berg C. A., Butner J., Hawkins M., . . . Yoon H. C. (2011). Affiliation and control during marital disagreement, history of divorce, and asymptomatic coronary artery calcification in older couples. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73, 350–357. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31821188ca [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A., Kivimäki M. (2013). Stress and cardiovascular disease: An update on current knowledge. Annual Review of Public Health, 34, 337–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer J. F., Ahs F., Fredrikson M., Sollers J. J., III, Wager T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: Implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36, 747–756. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer J. F., Lane R. D. (2007). The role of vagal function in the risk for cardiovascular disease and mortality. Biological Psychology, 74, 224–242. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treiber F. A., Kamarck T., Schneiderman N., Sheffield D., Kapuku G., Taylor T. (2003). Cardiovascular reactivity and development of preclinical and clinical disease states. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 46–62. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200301000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D. S. (2004). The Impact of Event Scale—Revised. In Wilson J. P., Keane T. M. (Eds.), Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD (Vol. 2, pp. 168–189). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.