Highlights

-

•

Iatrogenic pneumothorax should be anticipated during and after a CT guided transthoracic needle biopsy and actively treated.

-

•

Chest tube malposition is a common complication of tube thoracostomy.

-

•

Chest tubes should always be inserted in the triangle of safety described by the British thoracic society.

-

•

Debilitating subcutaneous emphysema which causes distress, anxiety, palpebral closure, dyspnoea or dysphagia requires intervention.

-

•

High negative pressure subcutaneous suction drains provide immediate and sustained relief in extensive and debilitating SE.

Keywords: Subcutaneous emphysema, Pneumothorax, Tube thoracostmy, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Subcutaneous emphysema is a common complication of tube thoracostomy. Though self-limiting, it should be treated when it causes palpebral closure, dyspnea, dysphagia or undue disfigurement resulting in anxiety and distress to the patient.

Presentation of case

A 72 year old man who was a known case of COPD on bronchodilators developed a large pneumothorax and respiratory distress after a CT guided transthoracic lung biopsy done for a lung opacity (approx. 3 × 3 cm) at the right hilar region on Chest X-ray. Within 24 h of an urgent tube thoracostomy, patient developed intractable subcutaneous emphysema with closure of palpebral fissure and dyspnea unresponsive to increasing suction on chest tube. A subcutaneous fenestrated drain was placed mid-way between the nipple and clavicle in the mid-clavicular line bilaterally. Continuous negative suction (-150 mmHg) resulted in immediate, sustained relief and complete resolution within 5 days.

Discussion

Extensive and debilitating SE (subcutaneous emphysema) has to be treated promptly to relieve patient discomfort, dysphagia or imminent respiratory compromise. A variety of treatment have been tried including infraclavicular blow-hole incisions, subcutaneous drains +/− negative pressure suction, fenestrated angiocatheters, Vacuum assisted dressings and increasing suction on a pre-existing chest tube. We describe a high negative pressure subcutaneous suction drain which provides immediate and sustained relief in debilitating SE.

Conclusion

Debilitating subcutaneous emphysema which causes distress, anxiety, palpebral closure, dyspnoea or dysphagia requires intervention. High negative pressure subcutaneous suction drain provides immediate and sustained relief in extensive and debilitating SE.

1. Introduction

Pneumothorax secondary to transthoracic needle biopsy (TTNB) is a common complication which has to be treated with tube thoracostomy in severe cases. Chest tube malposition and subcutaneous emphysema are common complications of tube thoracostomy.

Extensive and debilitating subcutaneous emphysema (SE) has to be treated promptly to relieve patient discomfort, dysphagia or imminent respiratory compromise. We describe a high negative pressure subcutaneous suction drain which provides immediate and sustained relief in debilitating SE.

2. Presentation of case

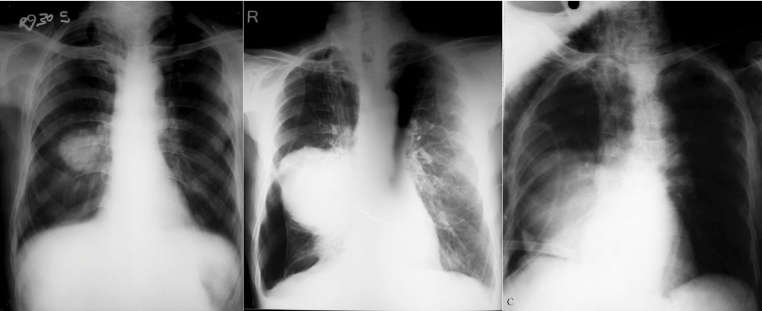

A 72 year old man who was a known case of Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was referred to us for evaluation of a lung opacity (approx. 3 × 3 cm) at the right hilar region. (Fig. 1A) He was chronic smoker (60 pack years).

Fig. 1.

(A) Chest X-ray PA view showing an opacity (approximately 3 × 3 cm) at the right hilar region with silhouette sign. Bilateral flattening of the diaphragms, a long narrow heart shadow, hyperlucency of the lungs with rapid tapering of vascular shadows are noted. (B) Chest X-ray PA view showing a large pneumothorax with a larger lung opacity than the previous X-ray. (C) Chest X-ray AP view (supine) showing chest drain in situ in the 7th right intercostal space pointing centrally and lying just above the right diaphragm.

Physical examination revealed a hyper-resonant chest on percussion, and prolonged expiration with wheezing on auscultation.

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy showed narrowing of lumen of Right upper, middle, and intermediate bronchus due to extrabronchial compression and bronchoscopic biopsy was inconclusive. Contrast enhanced CT(CECT) scan of chest revealed evidence of hypodense large well defined egg shaped solid mass lesion of size 6.7 × 5.7 cm noted in right middle lobe of lung in posterobasal segment with well-defined margins. Pulmonary function test (PFT) revealed a FEV1 (Forced expiratory volume1) to be 1.36/3.20, 43% of predicted value.

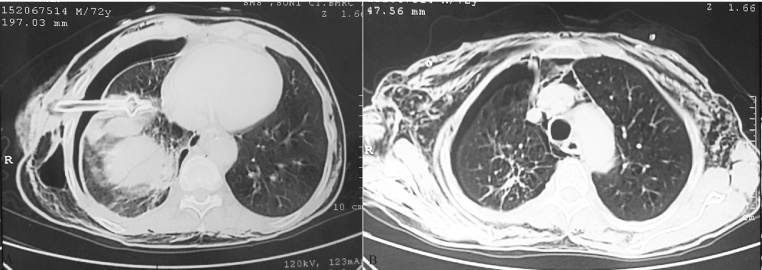

A CT guided transthoracic lung biopsy was done. Subsequently, the patient complained of dypnoea with decreased air entry on the right side and hyperresonant note on percussion. A chest X-ray confirmed a large Right pneumothorax. (Fig. 1B) An urgent bedside tube thoracostomy with a 32 F Malecot catheter was done and connected to an underwater seal. The patient’s condition improved and the pneumothorax resolved completely as seen on the repeat chest X-ray AP view but the tube was malpositioned in the 7th intercostal space and directed centrally. The tube was withdrawn by 2 cm. As the water column was moving and the lung had re-expanded, we decided to wait and watch. (Fig. 1C) There was a persistent air leak in the chest tube which made us suspect rupture of a large emphysematous bullae. The patient developed SE in the right chest wall which slowly progressed to the entire chest wall, abdomen, bilateral thighs, neck, face and bilateral palpebral fissures over the next 24 h. Eventually, the patient was unable to open his eyes and started complaining of dyspnoea and dysphagia. Applying negative suction on the chest tube upto − 40 cm of water did not relieve the condition. Since the first chest tube was functioning and the lungs had re-expanded we decided against using a second chest tube which would have been more invasive option than a subcutaneous suction drain under high negative suction pressure. Two 1.5 cm horizontal incisions were made in the skin and subcutaneous tissue bilaterally in the anterior chest wall mid-way between the nipple and the clavicle in the mid clavicular line. A plane was created just above the pectoralis fascia using a hemostat forceps. We inserted the fenestrated limbs of a readily available 12 F negative suction subcutaneous drain (Romo Vac Set, Romsons International, Noida, India). The efferent limb of the drain was attached to the negative pressure suction apparatus at a continuous high pressure of − 150 mmHg. A manual compression massage was done form the face downwards to force the already trapped air towards the fenestrated limbs. There was an immediate relief to the patient and the patient could open his eyes immediately (Fig. 2). The pressure applied was constant at − 150 mmHg. A repeat CECT thorax showed the chest tube to be located in the Right oblique fissure with marked right pneumothorax, extensive bilateral SE, presence of emphysematous bullae in bilateral lung fields, and a large heterogeneous density lesion with irregular margins in right lower lobe (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

(A) Extensive subcutaneous emphysema resulting in closure of palpebral fissures. (B) Patient sitting upright on his bed 10 min after insertion of a high negative pressure subcutaneous suction drain. (C) Patient is able to open his eyes after drain insertion. (D) Patient on post drain insertion day 2.

Fig. 3.

(A) Contrast enhanced CT thorax showing chest tube lying in the right oblique fissure, marked right pneumothorax, extensive bilateral subcutaneous emphysema, and a large heterogeneous density lesion with irregular margins in right lower lobe extending in right upper and middle lobe with size 100 × 93 × 107 mm which was predominantly necrotic with mild enhancement on post contrast scans. (B) Note the emphysematous bullae in bilateral lung fields.

The time to complete resolution was 5 days after which the subcutaneous drains were removed. The chest drain was removed on the 6th day post drain insertion as there was no air leak.

The patient was eventually diagnosed with Small cell cancer lung and is currently receiving Cisplatin-etoposide combination chemotherapy.

3. Discussion

The most common complications of transthoracic needle biopsy (TTNB) are pneumothorax (20.5%) and clinically significant hemorrhage (2.8%) [1]. Risk factors for developing a post-TTNB pneumothorax are increased depth of lesion, increased patient age, increased time of needle across the pleura, traversal of a fissure and presence of COPD and emphysema [2]. Most of these pneumothorax are self-limiting, but some intractable cases eventually require chest tube drainage.

The British thoracic society has described a triangle of safety for intercostal drain insertion bordered by the lateral border of the pectoralis major, anterior border the latissimus dorsi, a line superior to the horizontal level of the nipple and apex below the axilla [3]. Ball et al. described tube thoracostomy complications as insertional (visceral or parietal injuries of the intercostal artery or intra-parenchymal lung), positional (extrathoracic placement or atypical intrathoracic placement resulting in tube failure and replacement) or infectious (wound infection or empyema) [4]. In cases of malposition of chest tube, if a tube is inserted in the 5th, 6th or 7th intercostal space in the lateral chest wall and directed centrally, it is more likely to enter the oblique fissure [5]. Thoracic CT scan is the most reliable investigation to detect a mal-positioned chest tube [4]. In a review of 76 chest tubes placed in 61 patients by residents, there were 17 (22.4% per procedure) complications with non-surgical residents more likely to have complications [4].

Subcutaneous emphysema (SE) is common complication self-limited complication of tube thoracostomy. Any SE on positive pressure ventilation, causing palpable cutaneous tension, palpebral closure, dysphagia, and dysphonia or associated with pneumoperitoneum, airway compromise, “tension phenomenon” and respiratory failure is labelled extensive SE as defined by Srinivas et al. [6].

Usually, SE is due to a tear in lung tissue. After alveolar rupture, air preferentially moves from the pulmonary interstitium along the bronchovascular sheaths to the lung hilum from where it can pass superficial to the endobronchial fascia towards the thoracic inlet [7]. Therefore, the best site for decompressing SE is at the level of the thoracic inlet. In patients with tube thoracostomy for pneumothorax, SE can result if the parietal pleura is torn creating a pathway for the air into the subcutaneous tissue [8].

Various methods have been tried for managing extensive and debilitating SE. In the most comprehensive review of literature till date, Johnson et al. determined that no single method can be said to be the best method in the absence of randomized trials. Infraclavicular incisions, subcutaneous drains and increasing suction on an in situ chest drain all provided adequate relief. Selecting any method is dependent on patient factor and physician preference [9].

Fenestrated angiocatheters +/− manual compressive massage has been used with varying degrees of success. The most common drawback is the small luminal diameter which is susceptible to blockage. The time to complete resolution is also greater compared to other methods [10]. Repeated manual compressive massage increases the effectiveness but is cumbersome [6]. Subcutaneous drains using penrose-type small rubber tubes, Jackson-Pratt drains or Seldinger chest drains have been described to be effective [8], [11], [12]. Some of these methods have been assisted by repeated manual compression massage [12] or low level negative pressure suction [8], [11]. Infraclavicular blowhole incisions are an effective method of treating extensive SE though it needs regular dressing, has risk of infection, leads to an unsightly scar and eventually the tract closes [13]. Byun et al. have demonstrated Vacuum assisted closure therapy to be effective in 10 patients with ventilator associated massive subcutaneous emphysema at a pressure of − 150 mmHg. The mean duration of NPWT (negative pressure wound therapy) was 7.3 ± 4.8 days and the mean number of dressing changes were 1.4 ± 0.5 [14].

In conclusion, tube thoracostomy is an essential bed-side skill for surgical residents in particular and health-care professionals in general. Sub-cutaneous emphysema is a common self-limited complication of tube thoracostomy usually managed conservatively. Debilitating SE requires intervention. We describe high negative pressure suction subcutaneous drain which can provide quick and sustained relief in cases of extensive and debilitating SE.

Patient consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No sources of funding.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval not required.

Author contributions

Zeeshan Ahmed helped in conception and design of study, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article and final approval of the version to be submitted. Suresh Singh helped in analysis and interpretation of data, revising the article critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be submitted. Pinakin Patel helped in acquisition of data, revising the article critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be submitted. Raj Govind Sharma helped in analysis and interpretation of data, revising the article critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be submitted. Pankaj Somani helped in conception and design of the study, revising the article critically for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be submitted. Abdul Rauf Gouri helped in analysis and interpretation of data, revising the article critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be submitted. Shiv Singh helped in acquisition of data, revising the article critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be submitted.

Contributor Information

Zeeshan Ahmed, Email: drzeeshan180@gmail.com.

Pinakin Patel, Email: drpinakinp@gmail.com.

Suresh Singh, Email: drsureshsingh@gmail.com.

Raj Govind Sharma, Email: rajgovindsharma@gmail.com.

Pankaj Somani, Email: dr.pankajsomani@yahoo.com.

Abdul Rauf Gouri, Email: rauf.mbbs04@gmail.com.

Shiv Singh, Email: meena1989shivsingh@gmail.com.

References

- 1.DiBardino D.M., Yarmus L.B., Semaan R.W. Transthoracic needle biopsy of the lung. J. Thorac. Dis. 2015;7(suppl. 4):S304–S316. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.12.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boskovic T. Pneumothorax after transthoracic needle biopsy of lung lesions under CT guidance. J. Thorac. Dis. 2014;6(suppl. 1):S99–S107. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.12.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laws D., Neville E., Duffy J. BTS guidelines for the insertion of a chest drain. Thorax. 2003;58(suppl. 2):ii53–ii59. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.suppl_2.ii53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ball C.G. Chest tube complications: how well are we training our residents? Can. J. Surg. 2007;50(6):450–458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webb W.R., LaBerge J.M. Radiographic recognition of chest tube malposition in the major fissure. Chest. 1984;85(1):81–83. doi: 10.1378/chest.85.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srinivas R. Management of extensive subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum by micro-drainage: time for a re-think? Singapore Med. J. 2007;48(12):pe323–pe326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abu-Omar Y., Catarino P.A. Progressive subcutaneous emphysema and respiratory arrest. J. R. Soc. Med. 2002;95(2):90–91. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.95.2.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Reilly P., Chen H.K., Wiseman R. Management of extensive subcutaneous emphysema with a subcutaneous drain. Respirol. Case Rep. 2013;1(2):28–30. doi: 10.1002/rcr2.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson C.H. In patients with extensive subcutaneous emphysema, which technique achieves maximal clinical resolution: infraclavicular incisions, subcutaneous drain insertion or suction on in situ chest drain? Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2014;18(6):825–829. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leo F. Efficacy of microdrainage in severe subcutaneous emphysema. Chest. 2002;122(4):1498–1499. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.4.1498-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherif H.M., Ott D.A. The use of subcutaneous drains to manage subcutaneous emphysema. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 1999;26(2):129–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cesario A. Microdrainage via open technique in severe subcutaneous emphysema. Chest. 2003;123(6):2161–2162. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.6.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herlan D.B., Landreneau R.J., Ferson P.F. Massive spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema: acute management with infraclavicular blow holes. Chest. 1992;102(2):503–505. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byun C.S. Vacuum-assisted closure therapy as an alternative treatment of subcutaneous emphysema. Korean J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2013;46(5):383–387. doi: 10.5090/kjtcs.2013.46.5.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]