Abstract

The Department of Homeland Security's (DHS) Science and Technology (S&T) Directorate plays a role in public health that extends beyond biodefense. These responsibilities were exercised as part of the 2014-16 Ebola outbreak, leading to productive and beneficial contributions to the international public health response and improved operations in the United States. However, we and others have identified numerous areas for improvement. Based on our successes and lessons learned, we propose a number of ways that DHS, the interagency, and academia can act now to ensure improved responses to future public health crises. These include pre-developing scientific capabilities to respond agnostically to threats, and disease-specific master question lists to organize and inform initial efforts. We are generating DHS-specific playbooks and tools for anticipating future needs and capturing requests from DHS components and our national and international partners, where efforts will also be used to refine and exercise communication and information-sharing practices. These experiences and improvement efforts have encouraged discussions on the role of science in developing government policy, specifically responding to public health crises. We propose specific considerations for both scientists and government decision makers to ensure that the best available science is incorporated into policy and operational decisions to facilitate highly effective responses to future health crises.

The United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is not the first institution that comes to mind when considering contributors to the global public health response. That critical mission is performed by the World Health Organization, Médecins Sans Frontières, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and front-line healthcare workers, among many others. While DHS is extensively involved in health security, our mission equities focus less on international infectious disease outbreaks and more on biodefense. This distinction disappeared quickly and dramatically in late September of 2014 with the diagnosis of Ebola in Texas. This case was part of the 2014-2016 West Africa Ebola outbreak that resulted in more than 28,000 infections and at least 11,000 deaths. The outbreak spread to multiple countries around the world, including 11 cases in the United States.1,2

DHS had a multipronged approach in responding to the Ebola outbreak, consistent with Secretary Johnson's “Unity of Effort.”3 Customs and Border Protection (CBP) screening in airports was DHS's most visible public response. The Office of Health Affairs was responsible for workforce protection and medical matters for DHS employees. The Science and Technology (S&T) Directorate, our organization, provided subject matter expertise and laboratory experimentation to support operational responses and policy development by addressing key knowledge gaps in the understanding of the virus. As the outbreak abates, we in S&T are using both successes and lessons learned to improve our response framework to better respond to future biological events. More broadly, we hope to promote a discussion on the role of science, research, and actionable data in decision making during public health crises.

As a scientific community, the general response to a problem is to identify critical questions, determine how our capabilities can be best used to answer those questions, design and execute the necessary research, and then share those results. This approach, however, is challenged in public health crises where the need to act quickly and efficiently is in direct conflict with the desire to obtain the best scientific data. In fact, policy decisions in a crisis are often made in the “situation room” by those without a technical background and without the luxury of time to consult experts. Even when circumstances allow time to research an issue, there is a vast difference between data and actionable information. Actionable information needs to be data with a clear and relevant conclusion allowing risk-based decision making. The scientific community must ensure data are actionable in order to influence policy and tactical decisions in a crisis, while decision makers must seek out scientific input early and often. Both groups must work with a common set of goals to ensure actionable data become policy.

An ideal model to marry science and decision making is to have scientists involved in government in ongoing or permanent roles to inform data-based decisions and ensure science is funded, performed, and implemented to maximal utility. For example, DHS S&T is the department's primary research and development arm and technical core; one of our unique assets is the National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center (NBACC), a federally funded research and development center. NBACC is a government-owned, contractor-operated biological research laboratory with capabilities to address any biological material (biosafety levels 2-4) and a mission to conduct experiments specifically aimed at understanding and characterizing the threat from biological material. While NBACC primarily focuses on biodefense, the laboratory and S&T's scientific staff and resources can be rapidly redirected to respond to public health emergencies. Such was the case last year when DHS initiated an Ebola response, and this represented the first time that DHS S&T had responded to a public health crisis on this scale.

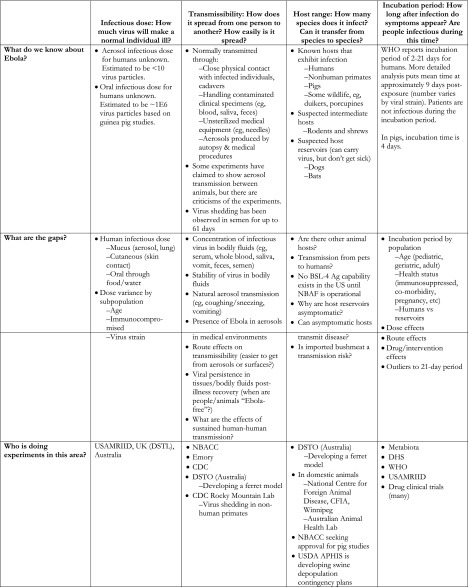

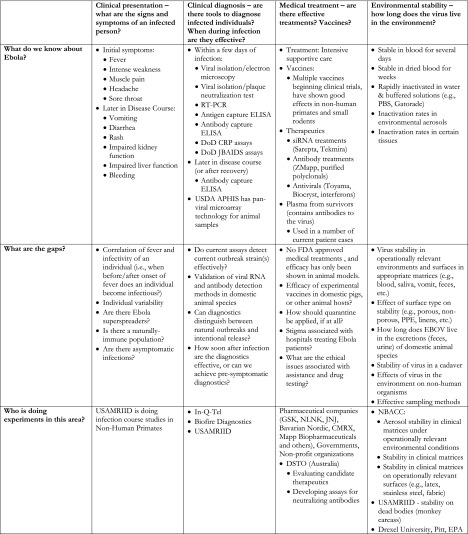

As co-chair of the White House Ebola Task Force, S&T's initial Ebola efforts were to collect and organize information relevant to the public health response so that the best available science would influence policy decisions. We developed an Ebola “master question list” (Figure 1) that identified what was known, what additional information was needed, and who was working to address such fundamental questions as, What is the infectious dose? and How long does the virus persist in the environment? The master question list served not only to present the current state of information to government decision makers and allow structured and scientifically guided discussions across the federal government, but it also prevented duplication of efforts by highlighting and coordinating research.

Figure 1.

Master Question List, November 2014. Information needed to effectively respond to the Ebola outbreak was organized according to what we know about Ebola, what knowledge gaps have been identified, and who is working to address these gaps. Questions are designed to be disease agnostic such that the master question list template can be used for a variety of diseases and disease agents.

Our organization fielded scores of requests for data and scientific support from within DHS and other federal agencies, as well as from Congress, academia, and the private sector. For some of these requests, research previously performed by the scientific community could be leveraged to quickly and effectively address concerns. Examples include the incubation period of the virus, the fact that infected individuals are not generally contagious before symptoms develop, and scientific research on airborne transmissibility. In other areas, neither S&T nor others had the necessary answers, so these requests were incorporated into the master question list as unknowns.

Together with the CDC, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Department of Defense, and the scientific community, we were able to prioritize the knowledge gaps most critical to the public health response and match them to existing expertise and capabilities, thus maximizing the support we could collectively contribute to the crisis. This coordination was formally led through the White House Ebola Task Force (part of the National Science and Technology Council) but was supported by an informal network of science and technology organizations in the federal government; it included government scientists’ ties to academic, nonprofit, and industry scientists.

We were even able to leverage international agreements to coordinate information sharing and research priorities with key allies abroad. It was very useful to have such agreements and partnerships in place, as developing new partnerships is burdensome and time-consuming, complicating the rapid response necessary in a crisis. Each organization shared not only their mission priorities and requests, but they also shared resources and capabilities to identify as a group where each of us could have the most impact while avoiding duplicative or competing research plans. DHS was best suited to address the ability of the virus to survive on common surfaces, which was linked to the concern of transmission in the absence of direct contact with an infected individual. This was a priority for public health and the protection of healthcare workers, and it fit with the DHS mission to establish operational requirements for CBP agents and first responders, while simultaneously benefiting federal agencies, hospitals and healthcare facilities, and airline and transportation providers. To highlight a few of the participating groups, the Department of Defense accelerated their longstanding investments in the development of Ebola virus vaccines, while the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) (NIH and CDC) took the lead on risk communication and patient treatment. We at DHS were able to leverage our previous Ebola biodefense expertise and pathogen stability determination capabilities. From this, we developed a research plan within our agreed on focus area and shared it extensively with our government partners, ensuring their feedback and requests were carefully considered. The value of this large-scale coordination is evidenced by the combined scientific efforts from September 2014 to May 2015 that addressed more than 20 of the critical gaps included in the Ebola master question list, as well as additional gaps that continue to be addressed.

Upon initiation of a DHS response to Ebola and prioritization of our research direction, NBACC began developing public health capabilities, including protocols to obtain and work with human bodily fluids. While NBACC was experienced with biodefense experiments in virus stability and decontamination, development of public health–specific capabilities required additional time. This delayed results by a number of months but also enabled a more thorough and productive response. NBACC determined the stability of Ebola virus on a variety of surfaces in relevant human clinical matrices (blood, feces, vomit) under environmental conditions representing an indoor hospital setting, outdoor West Africa conditions, and an airline cabin interior. Results showed that Ebola is highly stable in dried blood and remains infectious much longer than previously anticipated.

However, the virus was much less stable in vomit and appeared to be inactivated by feces.4 These results are directly applicable to protecting the general public and healthcare workers and are being used to inform practices and procedures in many areas, including keeping CBP agents safe as they oversee airports. These same results are improving policy for public health by identifying what bodily fluids present the highest risk of disease transmission and how to handle personal protective equipment (PPE) and medical waste.

Follow-up experiments were performed to determine the efficacy of several decontaminants to counter the significant viral stability and infectivity seen in dried blood; this effort was harmonized with a key US ally. By sharing data and research strategies, both countries advanced the state of knowledge faster and contributed jointly to a global response.

Despite a relatively fast and efficient response, results from both DHS and the broader scientific community were becoming available when the crisis was in decline rather than early on when actionable scientific data would have been more helpful. This time lag between identifying knowledge gaps and obtaining results is somewhat of a fixed cost and cannot be expedited except at the expense of data quality, quantity, or confidence. Results of single experiments could have been shared as they were obtained, but without replicates, controls, and careful analysis of the findings, acting on these preliminary data would have provided incorrect scientific justification for risky practices such as improper use of PPE, false confidence in decontamination and safety procedures, or unnecessarily inciting public fear. This would also have fostered public distrust of the scientific and medical communities.

We did, however, share preliminary results in real time with our interagency partners and presented confirmed results to the international public health community at scientific conferences. As DHS S&T is not the lead agency for public health, we relied on others for risk communication (including HHS, CDC, and others in DHS), allowing them to determine what should be shared with the public. We recognize that faster responses are necessary to control epidemics and that scientific support and actionable data must be available during the crisis to inform decision making. This difficult balance between reliable data and fast action in a crisis is exactly the dichotomy that public health responses need to reconcile. We believe pre-event preparation is the key to making actionable data available at the height of an outbreak, when it is most needed to inform decision making and policy. DHS S&T will continue making investments to develop the necessary programs, policies, and infrastructure to ensure that our pre-event preparation improves both the speed and impact of future responses. Our efforts are focused in 3 main areas, as detailed below.

Pre-develop Scientific Capabilities

While public health and biodefense often have overlapping elements, the capabilities needed to support each mission are not identical. Thus, the DHS scientific response to Ebola required initial investments of time and resources to develop additional capabilities and protocols, contributing to the time lag in obtaining actionable results. We are currently working to expand capabilities to hasten our next response, which should generate results weeks to months faster in the next crisis. This includes identifying and establishing protocols for working with a wide range of disease transmission matrices (ie, blood, sweat, tears, etc) and surfaces that may harbor microbes (eg, wood, carpet, furniture, clothing). By developing agent-agnostic capabilities, DHS S&T will be able to respond quickly and efficiently to a broad array of public health events, generating complete, informative, actionable data no matter what the future threats might be.

Identify Questions Before They Are Asked

Generating and using a master question list for Ebola was central to S&T's communication, research prioritization, and response. It allowed us to work closely across the federal government including HHS, DoD, and the White House via the Ebola Task Force through informal communication, regular meetings, scientific information sharing, and formal coordination to maximize unique resources and mission space while collectively supporting a synergistic response. It is by no means revolutionary that organizing known information and using it to make informed decisions is helpful, but a crisis response is less about breakthroughs and more about systematic application of tried and true principles.

We are currently working to develop master question lists for a number of diseases representing high-impact human health risks. These master question lists follow the same general structure as the Ebola list, with careful attention to ensure a broad applicability. For example, one category is “Decontamination: What are effective methods to neutralize the virus in the environment?” rather than Ebola-specific questions, such as “How are West Africa Ebola treatment units decontaminated?” These categories, as delineated for Ebola in Figure 1, allow a guided flexibility to adapt the master question list framework to a variety of pathogens. Master question lists will aid in research prioritization by identifying where current knowledge gaps reside, matching gaps to existing roles and responsibilities across the US government, and preventing duplication of effort. Developing these knowledge resources in advance will facilitate better communication and a faster, more organized response, both within DHS and across the federal government. This success was recently demonstrated with the Zika virus outbreak, where DHS developed a master question list, which was requested by and shared with departments across the interagency.

In addition, we have collected 76 scientific and technical questions asked of us in the frenetic days following the initial Ebola diagnosis in the United States,5 including questions from DHS components, academics, private companies, and US and international government groups. While some of these requests were specific to one group, many more were broadly applicable. Often, questions were relevant to multiple groups despite being asked by a single group. The majority of the requests could be answered from existing information, highlighting the need for scientific expertise to be available for crisis response. The questions affecting the broadest stakeholder base were regarding screening and surveillance (likely due to the fear of the virus entering the United States and spreading domestically). Analysis also showed that S&T had the most information to share, and the Office of Health Affairs was the biggest “customer” of this information (this group also had the largest overlap with CDC mission areas). Working together with the DHS offices of Policy, Health Affairs, and FEMA, S&T is helping our department define the requirements to codify and implement policy changes to improve future responses. This includes identifying the needs and responsibilities of each group and establishing best practices for information sharing between groups. We have identified what information was requested by each group to support their Ebola response, and we are asking them to expand that input by viewing all 76 requests to see where the needs and resources of others might be helpful. We will then attempt to extrapolate the needs and responsibilities to a broader, disease-agnostic set of requirements. These exercises will strengthen the communication infrastructure and highlight where information is available, leading to faster future responses for DHS and the federal government.

Communicate Through Established Positions

We never want a crisis, but one good thing that comes out of critical situations is that they bring people together in a unity of effort. DHS employees from all the components and scattered across the country were reaching out to each other to ensure a safe and effective response. By nature we always turn to those we know and trust, but an ad hoc communication network is not ideal, as it results in pockets of information sharing, filtering of requests and results, and exclusion of those who may not be connected but very much need to know. For example, the safety of reusable equipment was discussed extensively to ensure healthcare facilities would not inadvertently infect naïve patients and also to ensure that diagnostic samples were not contaminated by previously used equipment. Preexisting laboratory expertise was leveraged to alleviate concerns, and this information was broadly shared within ad hoc networks.

However, there were clear failures, such as when a new group was referred to DHS almost a year later asking the same questions. A faster, more effective, and broader network can be created by identifying positions rather than individuals. At DHS S&T, we have approached this problem through parallel top-down and bottom-up approaches, identifying the positions we think are relevant in each DHS component as well as asking components to identify relevant experts. In addition, future crises will be addressed through the strong executive secretariat system that exists for coordinating decision making and managing information flow. These communication mechanisms and experts will be part of the information-sharing exercises described above. All DHS components and elements will have the opportunity to promote the needs and capabilities of their organization, establishing formal relationships for future responses.

In a crisis situation, each party has a limited time-frame in which to contribute and have an impact. While no response will ever be perfect, we should all strive to use the best available data to make decisions. This is a responsibility for scientists as well as government decision makers. We propose specific considerations for each community.

For scientists: (1) Clearly define research in the context of the larger problem. Why should policymakers (and through them, the public) care about your research? How does your work improve policy and response? This can be set up in advance by developing research directions and project plans where applications (ie, guiding policy) are an end-goal. (2) Ensure results are actionable and clear; note risks, but do not obscure conclusions with an excess of footnotes and nuances. All information needs to contribute to increased confidence and improved risk-based analyses. (3) Present results in a way that will maximize their impact on nontechnical communities. Some scientific journals have begun to include a short author summary in addition to the abstract. This could be an ideal place to convey actionable results to decision makers in clear, nontechnical terms. The article will still contain all the relevant technical details, and those will be available to anyone reading the article, but this “executive summary” can concisely guide nontechnical audiences. After all, don't we all want to see our science improve the world? While all of this may be challenging, there are many great resources available to improve science communication skills, such as the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University or the American Association for the Advancement of Science, among others.

For government decision makers, we recommend actively seeking out and leveraging scientific information and experts when making decisions and determining policy. Increasingly, science and technology are inextricably dual-use, meaning that they drive both new threats and the needed solutions to our nation's challenges. Cultivation and use of a technical core is inextricably linked to meeting the demands of the future, and experts are necessary to help chart a successful course. We at DHS S&T are developing a new initiative called the Science Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) to help us incorporate science early and often in decision-making processes. This effort pre-identifies scientists in academia or private industry with recognized expertise pertaining to DHS mission areas who are willing to be on stand-by to provide technical advice and support practical decision making based on actionable scientific data, particularly in the event of a crisis. To our colleagues in government, we are willing to share this “Rolodex of expertise.” And to our fellow scientists, if you are interested in joining the SAGE team, please contact DHS S&T.

At the time of this writing, there are a number of diseases threatening both the United States and international communities. The Zika virus outbreak has been declared a public health emergency, and MERS, chikungunya, avian influenza, and measles are also of concern. We want to prepare before an emergency to ensure that our response is better, faster, and cheaper, no matter what or where the disease might be. We need to develop protocols, methods, information resources, and communication plans as part of our response infrastructure and have that infrastructure and expertise embedded in our response plans before the next outbreak occurs. We need to work with the policy and technical communities to ensure that, where possible, actionable scientific data are used to shape decisions and guide operations. It is our hope that melding science, policy, and decision making will result in faster and more effective responses to future crises.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Ebola situation report. WHO website. October 21, 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/190067/1/ebolasitrep_21Oct2015_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 Accessed June16, 2016

- 2.Heavey S, Jenkins C, Kerry F. Factbox: Ebola cases in the United States. Reuters March 12, 2015. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-ebola-usa-cases-factbox-idUSKBN0M82T120150312 Accessed June16, 2016

- 3.Johnson J. Strengthening departmental unity of effort. Memorandum for DHS leadership. April 22, 2014. http://www.hlswatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/DHSUnityOfEffort.pdf Accessed June16, 2016

- 4.Schuit M, Miller DM, Reddick-Elick MS, et al. Differences in the comparative stability of Ebola Virus Makona-C05 and Yambuku Mayinga in blood. PLoS One 2016;11(2):e0148476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC and Texas Health Department confirm first Ebola case diagnosed in the U.S. [press release]. September 30, 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/s930-ebola-confirmed-case.html Accessed June16, 2016