Abstract

Eighteen cases of disease caused by the saprophytic fungi Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus bacillisporus are described from the Northern Territory of Australia. The majority of infections were with Cryptococcus bacillisporus and in the rural Aboriginal population, often causing pulmonary mass lesions.

Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus bacillisporus are encapsulated yeast-like fungi. C. neoformans var. neoformans (formerly known as C. neoformans var. neoformans serotype D) and C. neoformans var. grubii (formerly known as C. neoformans var. neoformans serotype A) have a worldwide distribution, particularly in pigeon droppings (4). In Australia, C. bacillisporus (formerly known as C. neoformans var. gattii serotypes B and C) has been found to be especially associated with eucalyptus trees, most notably the river red gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis). However, other environmental niches have been long suspected, as the highest incidence rates for C. bacillisporus occur in regions of the Northern Territory (NT) of Australia and Papua New Guinea, where E. camaldulensis is not endemic (3). Recently a number of other eucalypt species have been associated with C. bacillisporus in temperate Australia (6).

In Australia, both C. neoformans and C. bacillisporus disproportionately affect Aboriginal people. The population-based rates for C. neoformans are 8.5 versus 4.4 cases per million persons (indigenous versus nonindigenous), and those for C. bacillisporus are 10.4 versus 0.7 cases per million persons (2). In Arnhemland (rural home to many remote Aboriginal communities), the relative risk for cryptococcal disease for Aboriginal compared with nonindigenous people is 20.6 (5).

We present data from 18 patients treated at the Royal Darwin Hospital (RDH) between 1993 and 2000. RDH is the tertiary referral center for the “Top End” of the NT, servicing 670,000 km2 and approximately 140,000 people.

Cryptococcal disease was diagnosed when patients had a positive culture for the fungus or had signs and symptoms of central nervous system (CNS) or pulmonary disease and a positive cryptococcal antigen. Cultures were performed on selective agar, and identification and typing were performed by the Women's and Children's Hospital, Adelaide, South Australia.

Of the 18 cases, 17 patients were from rural areas and 9 were women. Twelve cases were due to C. bacillisporus (median age, 39 years; range, 5 to 64 years), and 5 were confirmed as C. neoformans (median age, 46 years; range, 22 to 76 years). One case was diagnosed by positive cryptococcal antigen serology. Thirteen cases of pulmonary disease were diagnosed (6 with concurrent CNS disease). Four patients had CNS disease alone, and one individual had positive blood cultures with no evidence of lung or CNS disease. The fifteen patients tested for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody were all negative. Four patients in this series died; all were infected by C. bacillisporus causing pulmonary disease (two), CNS disease (one), and combined pulmonary/CNS disease (one). Four patients required surgery: two had large lung cryptococcomas excised, and two others had ventricular shunts for the control of raised cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure.

Of the 10 patients with CNS disease, time from onset of symptoms to presentation ranged from 1 day to 3 months (median of 1 week). At presentation, seven patients had an altered conscious state, six had headaches, five had seizures, and four reported vomiting. Three had papillitis/papilledema on fundoscopy. Nine underwent computed tomography (CT) scanning or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, with results for five patients being abnormal. CSF was culture positive in 8 of 10 patients, India ink staining showed cryptococci in 6 of 10 patients, cryptococcal antigen was positive in 8 of 8 patients, and CSF lymphocyte levels were elevated in 9 of 10 patients. (One patient on immunosuppressive therapy was culture positive without the presence of CSF leukocytes.)

The eight patients who survived all received amphotericin (mean dose, 1,602 mg; range, 626 to 3,430 mg) over an average of 43 days (range, 28 to 90 days). They all received 5-flucytosine, and seven were discharged on oral fluconazole therapy (100 to 800 mg daily for a mean duration of 215 days [median, 90 days; range, 30 to 702 days]).

For the 13 patients with pulmonary disease, the time from initial symptoms to presentation ranged from 1 day to 3 months (median, 2 weeks). At presentation, nine patients had cough, six had dyspnea, and five described sputum production. All 13 patients were culture positive for Cryptococcus from sputum or lung washings/fine-needle aspiration, and all had an abnormal chest radiograph (CXR): one or more mass lesions or nodules (on CXR and/or pulmonary CT) in eight instances and infiltration or consolidation reported in the other five.

All patients who survived received amphotericin: the mean dose was 992 mg (range, 360 to 1,450 mg) for an average duration of 34 days (range, 12 to 69 days). Eight patients received 5-flucytosine concurrently, and eight were discharged with oral fluconazole at 100 to 800 mg per day for a mean duration of 188 days (range, 30 to 480 days).

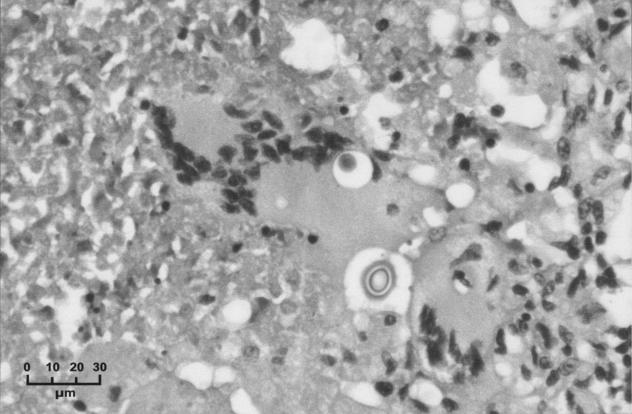

The histopathological findings from six cases of pulmonary cryptococcosis (three from the present series and three earlier cases) were reviewed. All revealed abundant round organisms consistent with Cryptococcus that stained positively with mucicarmine, periodic acid-Schiff, and silver staining. Prominent necrotizing granuloma formation was present in five of the six specimens. In addition, a predominantly monocytic (histiocyte) infiltrate was seen with occasional multinucleated giant cells associated with the cryptococci. In the sixth case, the cryptococci were seen in an inflammatory infiltrate that lacked granuloma formation and fibrinous necrosis. This was most in keeping with an acute severe infection. Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate the macroscopic and microscopic findings from a cryptococcoma successfully removed from a 39-year-old patient (case 12, Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Macroscopic specimen of a well-circumscribed cryptococcoma in the left lower lobe of 39-year-old man (Table 1, case 12).

FIG. 2.

High-power view of a granuloma from the excised crytococcoma showing a giant cell containing cryptococci with a clear halo indicating the nonstaining capsule (hematoxylin and eosin).

TABLE 1.

Eighteen cases of Cryptococcus infection in the NT

| Case | Age (yr)/sex of patienta | Ethnicity | Location | Species | Presentation | CXR/CT/MRI result | Comment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 49/F | Aboriginal | Rural | C. bacillisporus | Pulmonary and CNS | CXR, consolidation and cryptococcoma, CNS/MRI, CNS/CT, normal | Excisional lung surgery | Survived |

| 2 | 62/M | Aboriginal | Rural | C. neoformans | Pulmonary | Pulmonary/CT, mass lesion | Survived | |

| 3 | 64/M | Aboriginal | Rural | C. bacillisporus | Pulmonary and CNS | CXR, bronchopneumonia CNS/CT, CNS/MRI, hydrocephalus and multiple cryptococcomas | Ommaya reservoir | Survived |

| 4 | 46/M | Aboriginal | Rural | C. bacillisporus | Pulmonary | CXR, lung infiltrate | No therapy | Died, postmortem diagnosis |

| 5 | 25/M | Aboriginal | Rural | C. neoformans | Pulmonary | CXR, consolidation | Survived | |

| 6 | 38/F | Aboriginal | Rural | C. bacillisporus | Pulmonary | CXR and pulmonary/CT, multiple mass lesions | Survived | |

| 7 | 26/M | Non-Aboriginal | Rural | C. neoformans | Pulmonary | CXR and pulmonary/CT, multiple nodules plus cavity | Survived | |

| 8 | 39/M | Aboriginal | Rural | C. bacillisporus | Pulmonary, CNS, and blood subtypes | CXR, bilateral infiltrate CNS/CT, normal | No therapy | Died, postmortem diagnosis |

| 9 | 57/F | Aboriginal | Rural | C. bacillisporus | Pulmonary | CXR, pulmonary/CT, multiple mass lesions | Survived | |

| 10 | 5/F | Aboriginal | Rural | C. bacillisporus | Pulmonary and CNS | CXR, bilateral infiltrates, mass lesion (abscess cavity) | Survived | |

| 11 | 53/F | Aboriginal | Rural | C. bacillisporus | Pulmonary | CXR, severe bilateral pneumonia | 2 days of therapy | Died 2 days postdiagnosis |

| 12 | 39/M | Aboriginal | Rural | C. bacillisporus | Pulmonary and CNS | CXR and pulmonary/CT, large left LL mass CNS/CT, 2 mass lesions | Excisional lung surgery | Survived |

| 13 | 76/M | Aboriginal | Rural | C. neoformans | CNS | CXR, clear CNS/CT, no mass lesion | Survived | |

| 14 | 46/M | Aboriginal | Rural | C. bacillisporus | CNS | CXR, clear CNS/CT, CNS/MRI, paraventricular lesions | Survived | |

| 15 | 22/F | Aboriginal | Rural | C. bacillisporus | CNS | CNS/CT, CNS/MRI, hydrocephalus, no mass | Survived | |

| 16 | 28/F | Aboriginal | Urban | C. neoformans | Blood cultures only | CXR, CNS/MRI, both normal | Survived | |

| 17 | 49/F | Aboriginal | Rural | C. bacillisporus | CNS | CXR, normal CNS/CT, no mass | Ommaya reservoir | Died bacterial infection of reservoir |

| 18 | 44/F | Aboriginal | Rural | Serology | Pulmonary and CNS | CXR, consolidation pulmonary/CT, mass lesion CNS/MRI, mass lesion | Survived |

M, male; F, female.

Conclusions.

Case series of cryptococcal disease in the NT have been reported twice—in 1976 (7) and 1993 (5), totaling 61 cases in 35 years. In our series of 18 cases, over the subsequent 8 years, the trends are similar—a significant number of cases of infection are with C. bacillisporus, from a mainly rural and aboriginal population. Pulmonary disease continues to be prominent (2/3 of cases in our series). The NT pattern of disease is considerably different from findings in the region as a whole. Chen et al. (3), for the Australasian Cryptococcal Study Group, found 312 cases of cryptococcal disease in Australia and New Zealand between 1994 and 1997: 85% were due to C. neoformans infections (the majority were meningitis), and 79% of these were in immunocompromised patients. There were just 47 infections due to C. bacillisporus.

Radiological findings of pulmonary cases always showed abnormalities in our series, but this was variable (e.g., showing mass lesions, consolidation or infiltrations). A survey in the NT of 44 consecutive HIV antibody-negative patients with cryptococcal disease between 1976 and 1997 revealed that 52% of those with meningitis had an abnormal CXR (usually a mass lesion). Patients presenting with respiratory symptoms usually had air space consolidation (11).

Our treatment regimens were not dissimilar to those recommended by the Mycoses Study Group Cryptococcal subproject (United States) for treatment of well-established disease in HIV antibody-negative people (12). Many of our patients presented quite late, and their disease was not mild enough to warrant just oral (fluconazole or itraconazole) therapy as suggested in the literature (1, 8, 10). However, recent data have shown that voriconazole may have greater activity than either fluconazole or itraconazole and perhaps will become an important alternative (9).

In summary, Cryptococcus is an important cause of pulmonary and CNS disease in the NT, with C. bacillisporus being the species most frequently diagnosed, despite its environmental niche remaining uncertain. Mass lung lesions are common, and surgery may still be required.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aberg, J. A., L. M. Mundy, and W. G. Powderly. 1999. Pulmonary cryptococcosis in patients without HIV infection. Chest 115:734-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen, S., T. Sorrell, G. Nimmo, B. Speed, B. Currie, D. Ellis, D. Marriott, T. Pfeiffer, D. Parr, K. Byth, et al. 2000. Epidemiology and host- and variety-dependent characteristics of infection due to Cryptococcus neoformans in Australia and New Zealand. Clin. Infect. Dis. 31:499-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, S. C. A., B. Currie, H. M. Campbell, D. A. Fisher, T. J. Pfeiffer, D. H. Ellis, and T. C. Sorrell. 1997. Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii infection in Northern Australia: existence of environmental source other than known host eucalypts. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 91:547-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diamond, R. 2000. Cryptococcus neoformans, p. 2707. In G. L. Mandell, J. E. Bennett, and R. Dolin (ed.), Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 5th ed. Churchill Livingstone, New York, N.Y.

- 5.Fisher, D., J. Burrow, D. Lo, and B. Currie. 1993. Cryptococcosis neoformans in tropical northern Australia: predominantly variant gattii with good outcomes. Aust. N. Z. J. Med. 23:678-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halliday, C. L., T. Bui, M. Krockenberger, R. Malik, D. H. Ellis, and D. A. Carter. 1999. Presence of α and a mating types in environmental and clinical collections of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii strains from Australia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2920-2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lo, D. 1976. Cryptococcosis in the Northern Territory. Med. J. Aust. 2:825-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nunez, M., J. E. Peacock, Jr., and R. Chin, Jr. 2000. Pulmonary cryptococcosis in the immunocompetent host. Therapy with oral fluconazole: a report of four cases and a review of the literature. Chest 118:527-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfaller, M. A., J. Zhang, S. A. Messer, M. E. Brandt, R. A. Hajjeh, C. J. Jessup, M. Tumberland, E. K. Mbidde, and M. A. Ghannoum. 1999. In vitro activities of voriconazole, fluconazole, and itraconazole against 566 clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans from the United States and Africa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:169-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powderly, W. G. 2000. Current approach to the acute management of cryptococcal infections. J. Infect. 41:18-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roebuck, D. J., D. A. Fisher, and B. J. Currie. 1998. Cryptococcosis in HIV negative patients: findings on chest radiography. Thorax 53:554-557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saag, M. S., R. J. Graybill, R. A. Larsen, P. G. Pappas, J. R. Perfect, W. G. Powderly, J. D. Sobel, W. E. Dismukes, et al. 2000. Practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:710-718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]