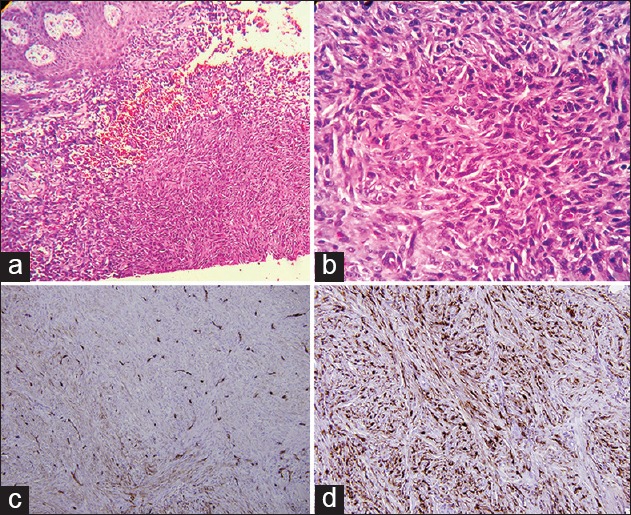

A 26-year-old healthy man was evaluated for a slowly growing, asymptomatic lesion on the medial aspect of his thigh of one year duration. The patient denied any history of trauma at the site. Physical examination revealed an indurated, nontender, brown, hyperkeratotic plaque on the medial side of his thigh [Figure 1]. The inguinal lymph nodes were not palpable. Excision biopsy was performed and, microscopically, a dermal-based spindle cell proliferation was present. The spindled cells were arranged in a storiform pattern [Figure 2a and b]. Mitotic figures were rare and none were atypical. Nuclear pleomorphism was mild, and there were no perivascular lymphoid aggregates. Immunohistochemical staining revealed scattered nuclear positivity for CD34 [Figure 2c] and HMB 45. S100 staining was negative. CD99 and Factor XIIIa [Figure 2d] demonstrated uniform nuclear expression in the tumor cells.

Figure 1.

Hyperkeratotic, hyperpigmented indurated plaque on the thigh

Figure 2.

Dermal spindle cell proliferartion in a storiform pattern (H and E): (a) Original magnification ×40; (b) Original magnification ×200); (c) Staining of spindle cells only at the periphery of the tumor (Immunostain CD34; original magnification ×200); (d) Strong expression in tumor spindle cells (Factor XIII a; original magnification ×200)

Diagnosis: Cellular Dermatofibroma

DISCUSSION

Dermatofibroma (DF) is a benign fibrohistiocytic tumor that is usually asymptomatic. It typically presents as a single skin-colored, red or red-brown, round or oval papule less than 1 cm in diameter presenting on the extremities of young to middle-aged patients.[1]

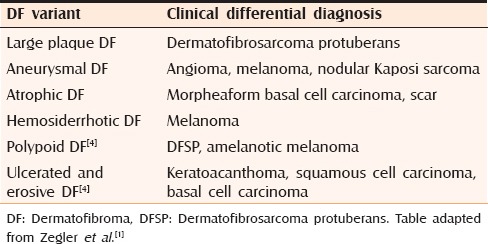

Dermatofibroma is characterized by a long list of variants; in 1994 LeBoit and Barr described 25 subtypes,[2] and Yus et al. added three additional subtypes in year 2000, namely, the lichenoid, erosive, and ulcerated types.[3] Several clinical variants of DF exist [Table 1].

Table 1.

Some DF variants with clinical differential diagnosis

Histopathologically, classic DF is characterized by a proliferation of spindle cells arranged in a storiform pattern in the mid to deep dermis and an overlying acanthotic epidermis, sometimes with follicular induction. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages (ringed siderophages) may be scattered and a proliferation of small vessels, some with a hyalinized vessel wall are typical. Cells at the periphery tend to surround small, rounded bundles of collagen. The tumor may extend deeply to the superficial fat, whereas the cellular DF variant shows hypercellularity and the spindled cells are usually arranged in a fascicular pattern infiltrating to the subcutaneous tissue as well as mitotic figures and mild cellular pleomorphism.[4] Atypical mitoses should not be seen.

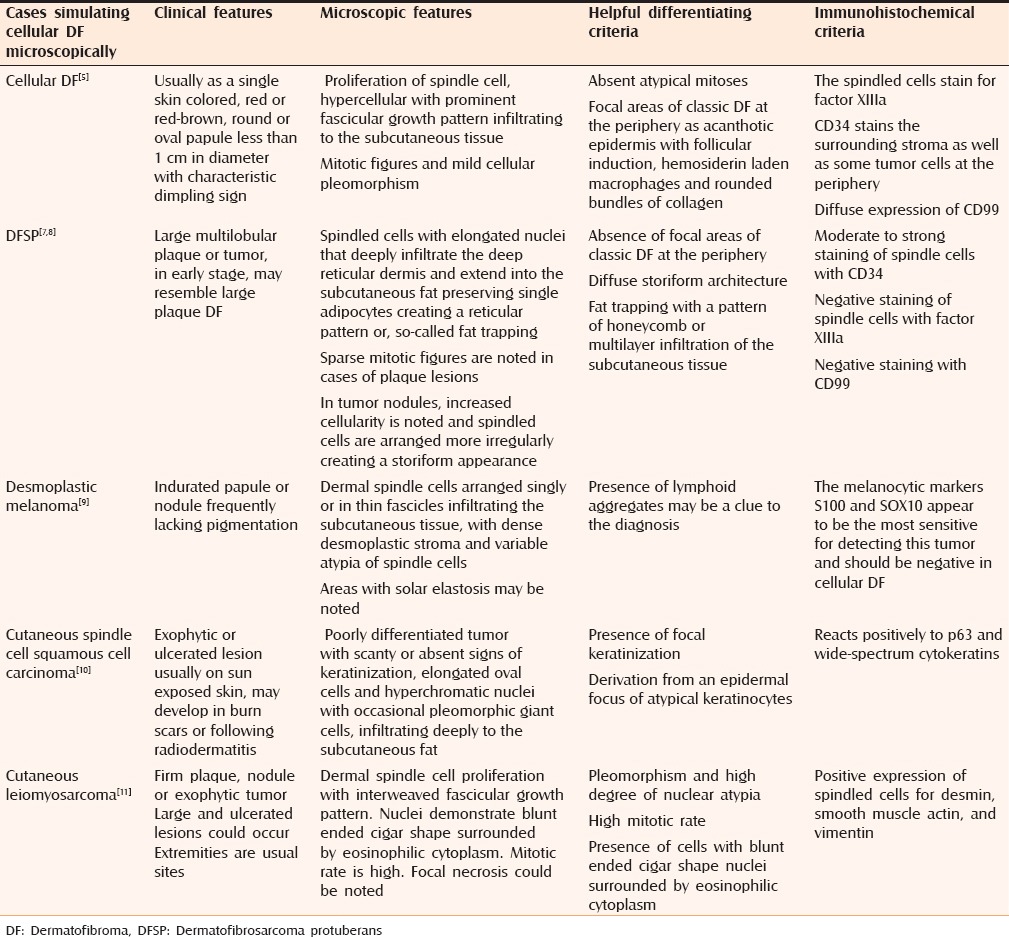

Cellular DF, sometimes referred to as an “indeterminate fibrohistiocytic lesion” due to the presence of overlap in histologic and immunopathologic characteristics between cellular DF and DFSP,[5] is particularly important to differentiate from DFSP [Table 2]. DFSP is an uncommon soft tissue sarcoma that is locally aggressive but has a high recurrence rate after wide local excision and a low rate of metastasis.

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis of cellular DF

The immunohistochemical staining pattern may aid in making the distinction. The spindled cells of cellular DF stain for factor XIIIa, whereas CD34 stains the surrounding stroma as well as some tumor cells at the periphery, whereas in DFSP there is moderate to strong CD34 staining of tumor cells diffusely.[6] In some cases, typically in superficial biopsies, CD34 and factor XIIIa may show overlap leading to difficulty in differentiating these tumors. False-positive CD34 staining often relates to the pH of the buffer solution, which can result in significant background staining. Careful interpretation of CD34 is important to prevent overinterpretation of background staining particularly at the periphery of the lesion.

Recently, CD99 was shown to be diffusely expressed in DF thus providing another potential option for distinguishing the two tumors.[7] Advanced techniques for distinguishing the tumors include fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) probe analysis for the t(17;22) translocation found in DFSP or array-based comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) assessment for DNA copy number changes.[8]

Other important differential diagnoses are desmoplastic melanoma, leiomyosarcoma, and cutaneous spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma [Table 2].

The recurrence rate of cellular DF is reported to be as high as 26% compared with classic DF, which has a low risk of recurrence (2%–3%) even if incompletely excised. Controversy regarding the optimal management of cellular DF exists. Rare reports of metastases and malignant transformation exist leading some authors to recommend complete excision or Mohs micrographic surgery as the treatment of cellular DF, especially in cases with an aggressive growth pattern.[1,12] Observation is considered acceptable by other authors, especially if immunostaining supports the diagnosis of a benign lesion.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zelger B, Zelger BG, Burgdorf WH. Dermatofibroma-a critical evaluation. Int J Surg Pathol. 2004;12:333–44. doi: 10.1177/106689690401200406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LeBoit PE, Barr RJ. Smooth-muscle proliferation in dermatofibromas. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:155–60. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199404000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sánchez Yus E, Soria L, de Eusebio E, Requena L. Lichenoid, erosive and ulcerated dermatofibromas. Three additional clinico-pathologic variants. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27:112–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2000.027003112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, Mckee P, Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, Mckee P. McKee's pathology of the skin with clinical correlations. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier Saunders, Fibrohistiocytic tumors; 2012. pp. 1643–62. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horenstein MG, Prieto VG, Nuckols JD, Burchette JL, Shea CR. Indeterminate fibrohistiocytic lesions of the skin: Is there a spectrum between dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans? Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:996–1003. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200007000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanmartín O, Llombart B, López-Guerrero JA, Serra C, Requena C, Guillén C. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007;98:77–87. doi: 10.1016/s0001-7310(07)70019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kazlouskaya V, Malhotra S, Kabigting FD, Lal K, Elston DM. CD99 Expression in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans and dermatofibroma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:392–6. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182a15f3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charli-Joseph Y, Saggini A, Doyle LA, Fletcher CD, Weier J, Mirza S, et al. DNA copy number change in tumors within the spectrum of cellular, atypical, and metastasizing fibrous histiocytoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:256–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanoma. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:321–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petter G, Haustein UF. Histologic subtyping and malignancy assessment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:521–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.99181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaddu S, Beham A, Cerroni L, Humer-Fuchs U, Salmhofer W, Kerl H, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:979–87. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199709000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doyle LA, Fletcher CD. Metastasizing “benign” cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma: A clinicopathologic analysis of 16 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:484–95. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31827070d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]