Abstract

BACKGROUND

Prior to withdrawing the EUS-FNA needle from the lesion, the stopcock of the suction-syringe is closed to reduce contamination. Residual negative pressure (RNP) may persist in the needle despite closing the stopcock.

AIMS

To determine if neutralizing RNP before withdrawing the needle will improve the cytology yield.

METHODS

Bench-top testing was done to confirm the presence of RNP followed by a prospective, randomized, cross-over study on patients with pancreas mass. Ten-mL suction was applied to the FNA needle. Before withdrawing the needle from the lesion, the stopcock was closed. Based on randomization, the first pass was done with the stopcock either attached to the needle (S+) or disconnected (S−) to allow air to enter and neutralize RNP and accordingly the second pass was crossed over to S+ or S−. On-site cytopahtologist was blinded to S+/S−.

RESULTS

Bench tests confirmed the presence of RNP which was successfully neutralized by disconnecting the syringe (S−) from the needle. Sixty patients were enrolled, 120 samples analyzed. S+ samples showed significantly greater GI-tract contamination compared to S− samples (16.7% vs. 6.7%, p=0.03). Of the 53 patients confirmed to have pancreas adenocarcinoma, FNA using S− approach was positive in 49 (93%) compared to 40 using the S+ approach (76%, p=0.02).

CONCLUSIONS

Despite closing the stopcock of the suction-syringe, RNP is present in the FNA needle. Neutralizing RNP prior to withdrawing the needle from the target lesion significantly decreased GI-tract contamination of the sample thereby improving the FNA cytology yield.

Keywords: Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), tissue acquisition, fine needle aspiration (FNA), Pancreas mass, Pancreas adenocarcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with fine needle aspiration (FNA) has evolved into the standard of care for tissue sampling of pancreatic masses and lesions adjacent to and within the wall of the gastrointestinal tract.1 The sensitivity and specificity of cytology obtained by EUS-FNA has been reported to be between 54% – 95% and 71% –100%, respectively.2 This wide range may be partly explained by different techniques in tissue acquisition.

Several factors influence the diagnostic yield of cytology specimens obtained by EUS-FNA. Endosonographer’s experience, needle diameter and type, method of aspiration and aspirate expression from the needle, availability of rapid on-site specimen evaluation, and the use of suction have all been reported to have an influence on the cytology yield.3–9 The use of suction during FNA of solid pancreas masses has been shown to increase the diagnostic yield, accuracy, sensitivity, and cellularity of the specimen.9 The speculated role of suction is to hold the tissue against the cutting edge of the needle rather than drawing cells into the needle.10 However, negative suction may also facilitate the acquisition of epithelial cells from the GI tract when the needle is withdrawn out of the target lesion into its outer sheath. Recognition of GI tract contamination in the aspirate is important to avoid misinterpretation of cytology specimens. To reduce the possibility of suction related contamination, the stopcock of the suction-syringe is closed prior to withdrawing the needle out of the target lesion. Despite this approach, a study on EUS-FNA of solid pancreas lesions revealed that up to 64% of specimens were contaminated with GI tract epithelial cells.11 GI tract contamination can result in cytology misinterpretation leading to either false positive or false negative diagnoses especially in the setting of paucicellular specimens with abundant surrounding GI epithelial cells.12 False negative diagnoses or low diagnostic sensitivity has been shown to occur in 4–45% of solid pancreas mass lesions while false positive diagnoses are estimated to occur in 5.3% of cases.13–16

We hypothesize that negative pressure still persists in the aspirating needle despite closing the suction-syringe stopcock; Residual Negative Pressure (RNP). We propose that the RNP can be neutralized by disconnecting the suction-syringe with the stopcock from the needle handle so as to allow air to enter the needle from the handle end thereby equalizing the pressure within the needle to atmospheric pressure. We believe that this maneuver decreases specimen contamination from GI tract cells allowing for improved cytology yield.

The aims of this study were to 1) assess whether RNP exists despite closing the stopcock of the suction-syringe and whether it can be neutralized by disconnecting the syringe from the needle, 2) assess whether RNP exists up to the tip of the needle rather than just proximal to the aspirated material, 3) If RNP exists, its influence on the cytology yield.

METHODS

Study Design

This study comprised of two components; a) bench-top testing and b) a prospective, single-blinded, randomized, cross-over pilot study on patients with solid pancreas masses. The study was conducted at one tertiary-care medical center and was approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board. All patients signed a written informed consent.

A) Bench-top Testing (Video)

In order to test the hypothesis that residual negative pressure (RNP) persists in the aspirating needle despite closing the stopcock of the suction-syringe, a vacuum gauge with leur lock connection was connected to the suction-syringe on the third port of a 3-way stopcock in series with a 22G FNA needle (Figure 1). The gauge pressure was calibrated to read 0” Hg for atmospheric pressure. The EUS needle was inserted into an ex-vivo chicken piece (breast) thawed to room temperature (simulating a target lesion). Suction was applied using a syringe and the needle-tip was moved back and forth in the simulated target lesion (Video A). Before withdrawing the needle-tip from the simulated target lesion, pressure measurements were obtained with a) suction stopcock open (Video A; Figure 1 A, stopcock open); b) suction stopcock closed but syringe still attached to the needle (Video A; Syringe-on: S+; Figures 1B and 2 A); and c) after disconnecting syringe with the stopcock from the needle handle (Video A; Syringe-off: S−; Figure 2 B) to allow air to enter the needle form its handle-end. To demonstrate that the RNP exists up to the tip of the needle rather than limited to the needle space proximal to the aspirated material, the needle was first flushed clean and the needle-tip then re-inserted in to the chicken piece. Suction was applied and the needle-tip moved back and forth. The stopcock was then closed and recorded negative pressure noted (Video B; S+ scenario; Figure 3 A). With the syringe still attached to the needle handle but stopcock closed, the needle-tip was withdrawn from the chicken piece (Video B; Figure 3 B) and the neutralization of the negative pressure (namely, air entering the needle from its tip-end was recorded; Video B). To determine consistency of the findings, bench top testing was done three times each.

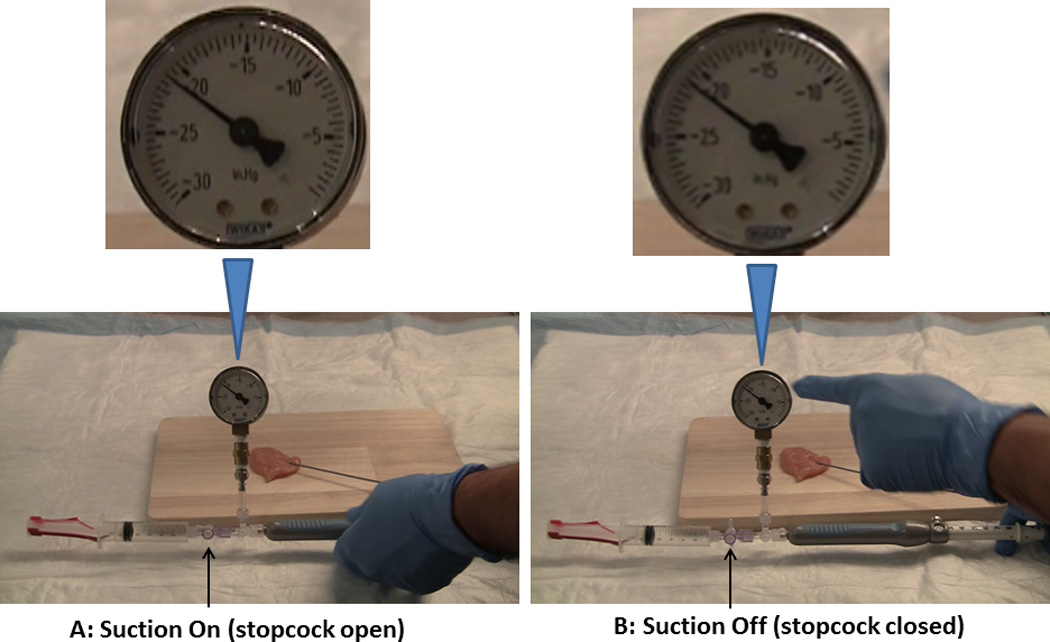

Figure 1. Fine needle aspiration: Suction On and Suction Off.

The EUS needle was inserted into an ex-vivo chicken thigh (simulating a target lesion). Suction was applied by opening the stopcock (A) and the recorded pressure was over minus (−) 20” Hg. Before withdrawing the needle-tip from the simulated target lesion, pressure measurements were also obtained with the suction stopcock closed but syringe still attached to the needle (Syringe-on: S+). Despite closing the stopcock the recorded pressure remained over minus (−) 20” Hg (B).

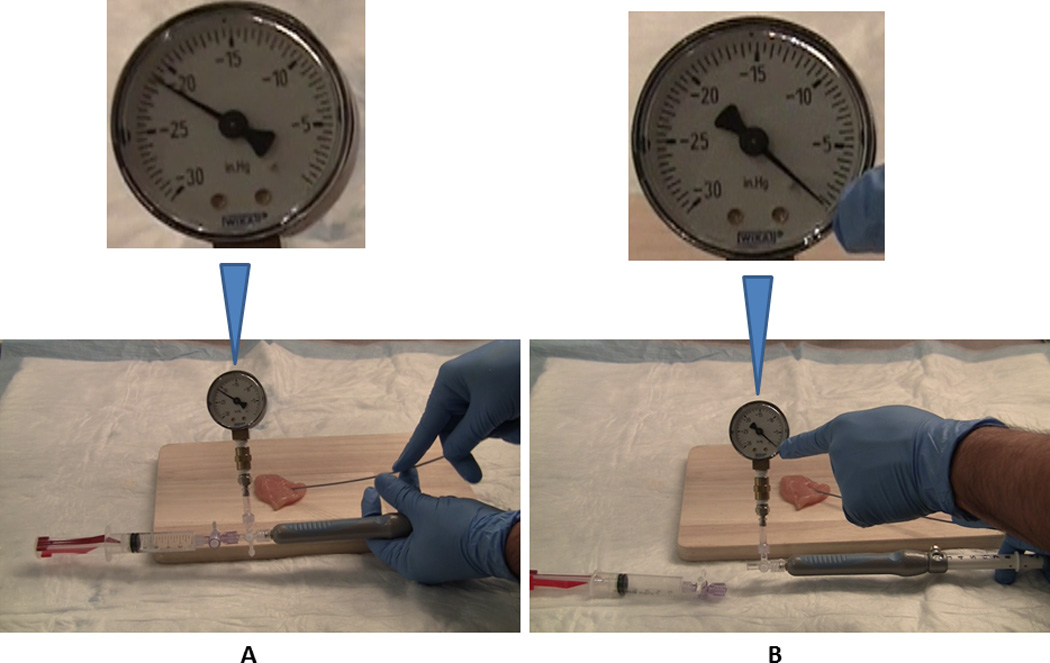

Figure 2. Fine needle aspiration with suction off and syringe (A): attached to and (B): detached from the needle.

With the stopcock closed and the needle-tip still within the simulated target lesion:

A: The residual negative pressure (RNP) recorded was over minus (−) 20” Hg with the suction-syringe and the stopcock still attached to the needle (Syringe On, S+).

B: Disconnecting syringe with the stopcock from the needle handle (Syringe Off: S−) neutralized the RNP by allowing air to enter the needle form its handle-end and the pressure reverted to 0” Hg.

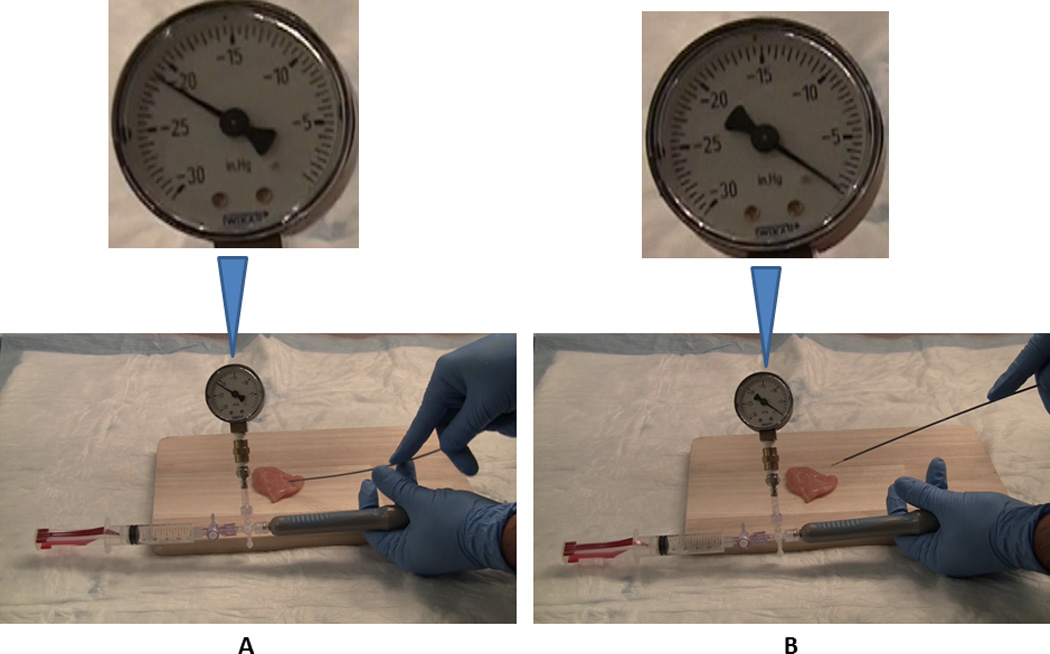

Figure 3. Fine needle aspiration with suction off and needle tip within the chicken and withdrawn from the chicken.

This figure demonstrates that the RNP exists up to the tip of the needle rather than limited to the needle space proximal to the aspirated material in a simulated lesion. Suction was applied and needle passes were made in standard fashion. The stopcock was then closed and the negative pressure recorded was over minus (−) 20” Hg (A; Syringe On, S+ scenario). With the syringe still attached to the needle handle and the stopcock closed, the needle-tip was withdrawn from the chicken piece (B). The pressure reverted to 0” Hg as air entered the needle from its tip-end thereby suggesting that RNP effect exists up to the needle-tip.

B) Patients

Patients with solid mass lesions identified on imaging studies (CT/MRI scans) and/or on EUS were prospectively enrolled over an 18-month period at one tertiary-care center. Inclusion criteria were age over 18 years, able to give informed written consent, stable to undergo EUS, mass seen on imaging studies (CT/MRI scan) or those with biliary obstruction without a distinct mass on CT/MRI but a mass seen on EUS. In the latter group, pre-procedure consent was taken and randomization was done during the procedure if a mass was discovered during EUS. Exclusion criteria included coagulopathy (one patient), inability to safely perform endoscopy/FNA (one patient with gastric outlet obstruction and food in stomach), and patient’s refusal to participate in the study (two patients worried about added risks of a second pass). Patients with a pancreas mass and metastatic disease seen on CT/MRI scan were not excluded as EUS-FNA of the pancreas mass was indicated to obtain tissue diagnosis. Patients with pancreas cysts without solid components were excluded.

EUS-FNA Procedure

All procedures were performed by 3 experienced endosonographers (KSD, YO, AK). The curvilinear array echoendoscope (GF-UC140P or GF-UCT140, Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) was used. For easier intubation of the duodenum, all EUS procedures were performed with patients in the left-lateral position under conscious sedation or under monitored anesthesia care. In patients with biliary obstruction, patients were then turned to the prone position for ERCP following EUS-FNA. Once the lesion of interest was identified, FNA was performed using a 22G needle (Echotip, Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC) using standard techniques as described below.

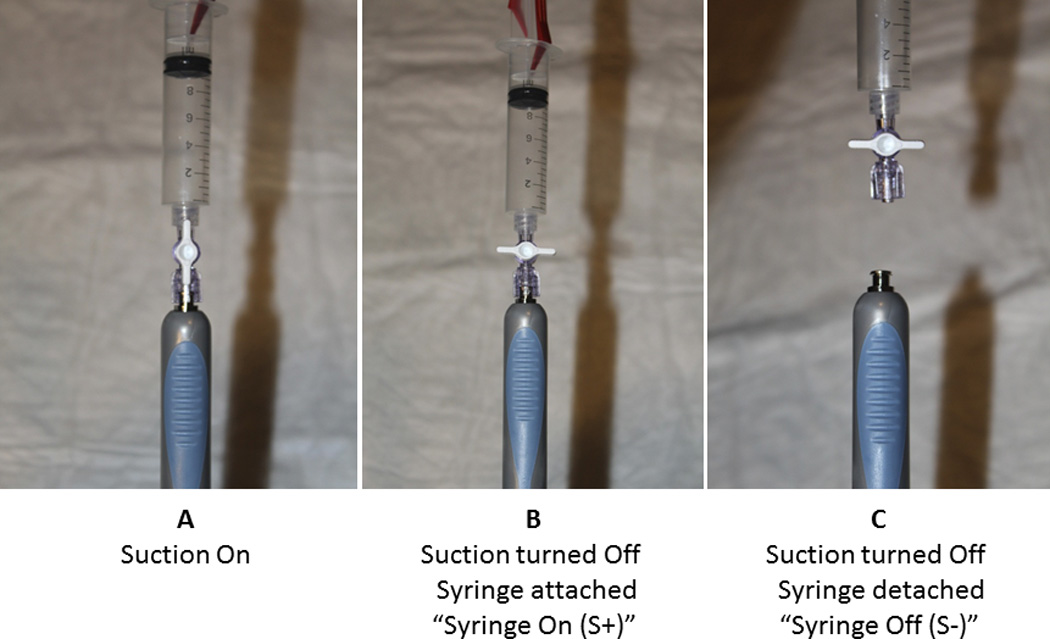

The needle assembly was passed through the accessory channel of the echoendoscope. After withdrawing the blunt-tip stylet a few mms into the needle, the sharp needle-tip was advanced into the target lesion under ultrasound guidance. The stylet was then pushed forwards to remove any tissue that may have entered the needle-tip while advancing the needle into the target lesion through the GI tract wall. Following this, the stylet was removed and a syringe with suction (10 mL, stopcock closed) was attached to the needle handle. The stopcock was opened and six back and forth passes were made making sure that the needle-tip remained within the mass during these movements. Before the needle was withdrawn from the target lesion, the stopcock was closed. The suction-syringe was then either left attached to the needle handle (Syringe-on: S+) or was disconnected from the needle (Syringe-off: S−) according to study randomization (Figure 4). The needle was then withdrawn from the target lesion.

Figure 4. A: Suction On, B: Suction Off syringe still attached (S+), and C: Syringe detached from the needle (S−).

Randomization

Patients were randomized to one of two arms, “Syringe-On” or “Syringe-Off”. Randomization was performed by a computerized binary random number generator. The order of EUS-FNA technique was determined using an opaque sealed envelope. Labels were printed with either “Syringe-On” or “Syringe-Off” and one label was pulled from the opaque sealed envelope by the endosonographer following patient enrollment into the study. The first pass was performed as indicated by the label, and the second pass was crossed-over to the alternative method. The numbers of back-and-forth movement within the lesion were same for both the passes (six). As per our protocol, only the first 2 passes per patient were used for S+ or S− randomization to determine if either S+ or S− was superior or both were inadequate. Once the diagnosis of malignancy was made by the on-site pathologist, additional passes were made to obtain more cells for molecular profiling using either S+ or S− technique based on which of the two approaches led to the diagnosis to begin with. Additional passes (frequently with a different or a tru-cut needle) were also made if both the first 2 passes (S+ and S−) were non-diagnostic.

Cytopathology Assessment

An on-site cytopathologist (VS, AR, BH) was present outside the procedure room for all cases and was blinded to the S+ or the S− status of the suction-syringe. Once a needle pass was completed, the sample was expressed onto a glass slide by reinserting the stylet into the needle. Smears were prepared by a cytopathology technician under the supervision of the cytopathologist. One slide was air dried and prepared with Diff-Quik stain for on-site analysis. The second slide was fixed in alcohol solution to be stained later with Papanicolaou stain. The cytopathologist looked at the stained slide onsite. The whole slide was examined. Contamination with gastrointestinal cells (duodenal or gastric depending on the approach used to FNA the pancreatic mass) in relation to total cellularity was recorded as percentage in quartiles (<25%, 25–50%, 50–75%, >75%). Cellular adequacy was defined as presence or absence of lesional cells on the slide irrespective of the contamination based on which a diagnosis could be (adequate) or could not be (inadequate) made. Based on the characteristics of the lesional cell and with additional staining in the cytopathology laboratory, a final diagnosis was made: adenocarcinoma, metastatic malignancy, neuroendocrine tumor, benign cell, or non-diagnostic. For masses suspected to be metastatic lesions in the pancreas, the cytopathologist also reviewed the slides of the primary tumor to look for similarities.

Diagnosis for malignancy was confirmed by surgical pathology of resected specimens serving as a gold standard in patients in whom surgery was performed. In those in whom surgery was not done (disease progression including metastasis during Neoadjuvant therapy), final cytology report on the FNA sample or biopsy of the metastatic lesion was used as confirmation of malignancy. In patients on whom surgery was not performed and the final FNA analysis was also negative for cancer, clinical and radiological imaging study follow ups over a minimum of at least 12 months was used as a reference.

Study Outcomes and Statistics

The primary endpoint assessed was GI tract contamination. Secondary outcomes were cellular adequacy and diagnostic yield of malignancy. Results for continuous variables are expressed by using mean ± standard deviation. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare paired data (S+ and S− samples obtained from each patient). Generalized estimating equation (GEE) regression modeling was used to account for clustering of observations within patients and to compare outcomes between S+ and S− groups. P value < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) and Stata 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas).

Sample Size

Due to the lack of data systematically looking at the prevalence of GI tract contamination during EUS-FNA, we decided a priori to enroll 30 patients and perform an interim analysis once our institutional data GI tract contamination was available. After interim analysis of data on 30 patients (60 FNA samples), we determined a sample size of 60 patients and 120 samples would be necessary to detect an absolute difference in GI contamination of 10% between S+ and S− groups with 80% power and a critical t of 1.98. The Institutional Review Board gave permission to prospectively enroll the additional 30 patients after we had prospectively enrolled the first 30 patients.

RESULTS

Bench Top Testing (video)

Suction was applied to a 22-gauge FNA needle with the needle-tip inserted into a simulated target lesion (chicken thigh piece). The pressures (mean ± SD) recorded with the stopcock open using 5 mL and 10 mL aspiration suctions in the syringe were minus (−) 17.5 0 ± 0.5” Hg and minus (−) 21.0 ± 0.5” Hg respectively (Table 1). With the needle-tip still within the simulated target lesion, when the stopcock was closed and the syringe was still attached to the needle (Syringe-On, S+), the pressures continued to stay at −17.5 0 ± 0.5” Hg and −21.0 ± 0.5” Hg for the 5 mL and the 10 mL syringes suctions respectively (Table 1, Figure 3). With the FNA needle-tip still within the simulated target lesion, once the stopcock with the suction-syringe was disconnected from the needle (Syringe-Off, S−), the pressure immediately returned to 0” Hg as recorded on the pressure gauge secondary to air entering the needle from its handle-end (Video A).

Table 1.

Bench top testing in Syringe-On and Syringe-Off positions with the needle-tip in a chicken piece.

| Syringe | Syringe Stopcock Open with Syringe Attached to the Needle mean ± SD |

Syringe-On Syringe Stopcock Closed but still Attached to the Needle mean ± SD |

Syringe-Off Syringe with Stopcock Disconnected from the Needle |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 ml | minus 17.5 ± 0.5” Hg | *minus 17.5 ± 0.5” Hg | 0” Hg |

| 10 ml | minus 21.0 ± 0.5” Hg | *minus `21.0 ± 0.5” Hg ” Hg | 0” Hg |

When the tip of the needle was withdrawn from the chicken piece, the pressure reverted to 0” Hg thereby suggesting that air entered the needle from its tip (video). Hence, despite a closed stopcock, the residual negative pressure within the needle exists up to the tip of the needle.

After cleaning the needle by flushing it with water and re-inserting the stylet, the Syringe-On scenario was repeated (stopcock closed, 10 mL aspiration suction-syringe still attached to the needle and the needle-tip inserted into the simulated target lesion). The stopcock was then opened. Again a −21” Hg pressure was recorded on the pressure gauge. The stopcock was then closed (still −21” Hg) and rather than disconnecting the syringe, this time the needle-tip was withdrawn from the simulated target. By doing so, the pressure swiftly, reverted to 0” Hg thereby suggesting that air entered into the needle from its tip-end implying that the RNP exists up to the tip of the needle (Video B) and not just limited to the needle compartment proximal to the aspirated material.

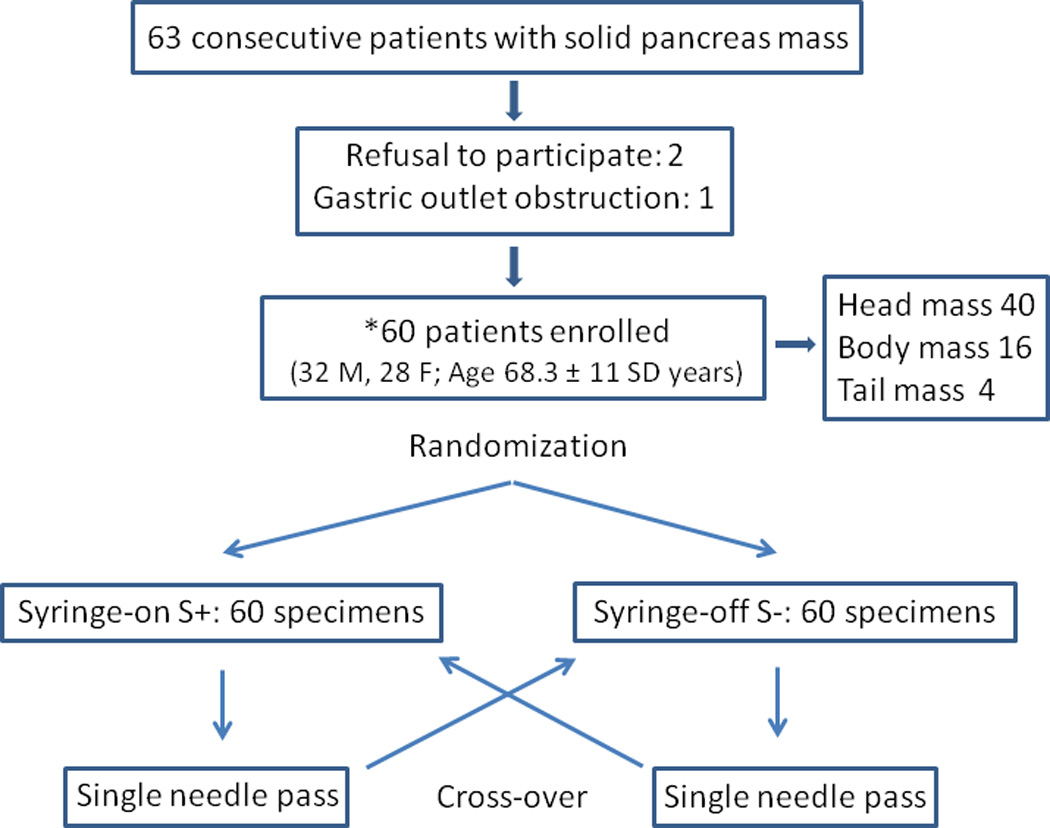

Patients

Sixty-three patients with solid pancreas mass lesions were considered for the study (Figure 4). Two patients were not willing to participate and one additional patient (uncinated-head pancreas mass) was excluded secondary to gastric outlet obstruction with food in the stomach. A total of 60 patients (32 men, 28 women; median age 69, range 39–88, mean [± SD] age 68.3 ± 11 years) were prospectively enrolled.

First two passes (as per randomization, first pass S+ or S− and the second pass the reverse of the first pass, Figure 4) in each patient (a total of 120 samples) were analyzed for study purposes. In 40 patients (67%), the lesion was located in the head of the pancreas. Fine needle aspiration was performed by the trans-duodenal approach in these patients. The trans-gastric approach was used in the remaining 20 of 60 (33%) patients. At the discretion of the endosonographer, a 22 gauge needle was used in 56 of 60 (93.3%) patients, while 25 gauge and 19 gauge needles were used in 3 (5%) and 1 (1.7%) patient respectively. EUS-FNA was technically successful in all patients.

In this cohort of 60 patients, 53 (88.3%) patients were diagnosed (FNA or surgery) to have pancreas adenocarcinoma. In the remaining patients, 3 (5%), had metastatic lesions in the pancreas, 1 (1.7%) had a neuroendocrine tumor, 1 (1.7%) had benign lymphoid tissue and in 2 (3.3%) patients, the FNA sample showed benign ductal cells. Additional passes with different FNA needle/tru-cut needle were made in these 3 patients (benign lymphoid cells 1, and benign ductal cells 2) which again did not show malignant cells. On longitudinal follow up over the next 18 months with interval abdominal scans, these patients remained stable.

Cytopathology

Contamination with GI epithelial cells was identified in 14 of 120 (11.7%) specimens (Table 3). S+ samples had significantly higher rates of contamination, compared to S− samples, (16.7% vs. 6.7%, p = 0.03). Only one S− sample contained >50% contamination compared to 6 S+ samples (p = 0.025). Overall cellularity was reported as adequate in 84 of 120 (70%) samples with a trend towards greater adequate cellularity observed when the RNP was neutralized by disconnecting the syringe (S− group); (S− 76.7% vs. S+ 63.3%, p = 0.10). Of the 53 patients eventually confirmed to have pancreas adenocarcinoma, FNA using S− approach was positive in 49 (92.5%) compared to 40 using the S+ approach (75.5%, p=0.02) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Contamination and diagnosis results for EUS-FNA of target lesions using the Syringe Off (S−) and the Syringe On (S+) techniques.

| Syringe Off (S−) (n = 60) |

Syringe On (S+) (n = 60) |

P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Contamination | |||

| < 25% | 56 (93.3%) | 50 (83.3%) | |

| 25–50% | 3 (5.0%) | 4 (6.7%) | |

| 50–75% | 1 (1.7%) | 3 (5.0%) | |

| 75–100% | 0 (0%) | 3 (5.0%) | |

| Contamination > 25% | 4 (6.67)% | 10 (16.67)% | 0.03 |

| Specimen Adequacy | 46 (76.7%) | 38 (63.3%) | 0.10 |

Table 4.

Diagnostic yield of malignancy in patients confirmed to have adenocarcinoma.

| Syringe Off (S−) | Syringe On (S+) |

P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Diagnostic Yield of Malignancy N = 53 |

49/53 (92.5%) | 40/53 (75.5%) | 0.02 |

Adverse events

There were no complications related to the EUS-FNA procedure in this study. Additionally, there were no reports of needle or syringe malfunction.

DISCUSSION

The ideal method to ensure optimal tissue acquisition during EUS-FNA has not yet been established. Although many endosonographers are not applying suction during tissue acquisition, studies published to date have not yet reached a consistent conclusion or consensus on the use of suction. Some randomized controlled trials have shown that suction did not improve diagnostic yield; however the majority of mass lesions in these studies were lymph nodes and therefore these results may not be applicable to solid pancreas masses.8,17,18 Bang and colleagues reported high diagnostic yield using FNA needle without suction while others have shown that the slow-pull or “capillary suction” technique by slowly withdrawing the needle stylet while obtaining samples resulted in a higher yield.19,20 Lee at al performed a randomized controlled trial on 81 patients with solid pancreas masses comparing cytologic features as well as diagnostic yield in samples obtained with and without suction.9 Samples obtained with the use of 10 mL suction had higher diagnostic yield (72.8% vs. 58.6%, p = 0.001), cellularity (OR: 2.12, 95% CI: 1.3–3.3, p < 0.001), and also greater accuracy (82.4% vs. 72.1%, p < 0.001) compared to samples obtained without suction. In a guideline review published by the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, the use of suction was recommended during FNA of solid masses, but no suction was recommended for FNA of lymph nodes.21 Additionally, the recently published ASGE technical review recommends considering the use of suction during FNA of pancreas mass lesions based on level 1 evidence.22

Based on our results, we believe that FNA with suction also allows acquisition of cells into the lumen of the needle rather than just its tip. For example, although not subject of this study, besides the first drop of the specimen (material from the tip) smeared on the slide showing cancer, the rest of the material squirted into the RPMI solution for cyto-block (material in the lumen of the needle) also showed cancer cells. Negative pressure in the FNA needle could potentially result in “contamination” of the FNA sample by non-target material like from the GI tract wall when the needle is being withdrawn from the lesion. To reduce the likelihood of contamination, traditionally the suction-syringe stopcock is closed before the needle is withdrawn from the target lesion on the assumption that by doing so, the needle no longer has negative pressure within its lumen. In this study we showed that this assumption is wrong. We hypothesized that residual negative pressure (RNP) persists in the needle despite closing the stopcock and that this negative pressure extends up to the tip of the needle rather than being limited to the needle space proximal to the aspirated material. Our bench-top testing results confirmed this to be true. Therefore, our results demonstrate that negative pressure induced by suction extends throughout the length of the needle allowing the acquisition of cells throughout the needle shaft. Residual suction within the needle shaft can decrease initial cytology yield as lesional cells could move higher into the needle shaft and less likely to appear on an the initial slide. This could have an impact the on-site diagnosis, the number of passes made, and clinical decisions such as whether to proceed with ERCP with metal stent placement. We hypothesized that neutralizing RNP decreases GI tract contamination thus avoiding misinterpretation of cytology specimens. This could improve the diagnostic yield of the sample obtained and thereby reduce the number of passes required to make a diagnosis and enhance the safety of the procedure. However, whether this residual negative pressure is just an epiphenomenon or it truly adversely affects the cytology yield outcome was not known. Hence as a second part to our evaluation, we performed a prospective, single blind, cross-over study on patients with solid pancreas mass lesions suspicious for cancer. Our results demonstrated that samples obtained using our modified suction technique by removing the stopcock with the syringe from the aspirating needle once tissue acquisition was completed (S−) and prior to withdrawing the needle out of the target lesion resulted in decreased GI contamination along with greater diagnostic yield. As shown in our bench-top study, by disconnecting the stopcock with the syringe, air enters the needle from its handle-end and neutralizes any residual negative pressure within the needle. We believe this resulted in less contamination of the aspirated cells from the target lesion as was shown by our on-site cytopathologist who was blinded to the method of aspiration. The rate of GI tract cell contamination in a study done by Rastogi et al on 472 EUS-FNA samples was 16%, while Kudo et. al reported contamination in 13% of samples utilizing standard suction technique.23,24 In comparison, we found a significant reduction in GI tract contamination once RNP was neutralized (6.7% versus 16.7% in control samples). We utilized rapid on-site cytopathology evaluation, which likely explains our excellent rates of diagnostic cytology yield, similar to multiple studies that have demonstrated higher yield with the use of on-site cytopathology.6,25–27

There are some limitations to this study. We did not perform an intra/inter-observer agreement analysis amongst our cytopathologists. A single cytopathologist scoring all slides would have been ideal but secondary to the great demands on our cytopathology service, this was not possible. However, amongst all our cytopathologists, we selected only three senior faculty members with several years of experience. Moreover, each pair of slides (S+ and S−) on the same patient was scored by the same cytopathologist. Another limitation of this study is that the 22G FNA needle was used in majority of the patients as has been the routine clinical practice at this center. Hence we did our bench studies using the 22G FNA needle. However, although a recent technical review on EUS tissue acquisition acknowledged the use of a 25G needle was associated with higher diagnostic yield, the quality of evidence for this recommendation was moderate, and the strength of recommendation was weak22. In this study we did not evaluate additional passes beyond the first two (crossed over passes after initial randomization). Our study design required paired samples and our clinical practice has been to obtain a minimum of two FNA passes and conclude the procedure once the cytopathologist has indicated that the cells unequivocally demonstrates malignancy. Additional passes besides the first 2 were primarily made to obtain more cells for molecular profiling. At our institution, immediate on-site diagnosis is also important since all patients with resectable pancreas cancer receive neoadjuvant chemoradiation for 3–4 months and hence, for durable biliary drainage, require a short self-expandable metal stent placed immediately after the EUS if the FNA is positive for cancer. This not only expedites treatment but also saves the patient from having two procedures done on different days. Since tissue diagnosis is essential for neoadjuvant therapy, we performed EUS-FNA even on those with a high pre-procedure probability of pancreas cancer (for example, elderly patient with weight loss, jaundice, mass on CT scan, high CA19-9). This could have biased our results towards a high malignancy-positive FNA cytology and may limit the broad application of our results to practice patterns in other medical communities.

In conclusion, following back-and-forth movement of the FNA needle in the pancreatic mass, despite closing the stopcock of the suction syringe before withdrawing the needle from the target lesion, residual negative pressure persists in the FNA needle. This negative pressure extends up to the tip of the needle and can adversely affect the cytology yield of the aspirated material. Eliminating the residual negative pressure by allowing air to enter the needle by disconnecting the syringe from its handle-end decreased GI tract contamination and improved the diagnostic yield of the aspirated material. Further randomized controlled trials comparing this method to standard suction as well as to no suction are recommended.

Figure 5. Flow diagram of the patients studied and randomization with cross-over.

Table 2.

Patient and lesion characteristics

| No. of patients | 60 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 68.3 ± 11 | |

| Male (%)/Female (%) | 32 (53.3%)/28 (46.7) | |

| No. of samples analyzed | 120 (first 2 samples randomized to syringe- on/off and crossed over) |

|

| Final confirmed diagnosis of patients included in the study N (%) |

||

| Adenocarcinoma | 53 (88.3%) | |

| Metastasis | 3 (5.0%) | |

| Benign ductal cells | 2 (3.3%) | |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 1 (1.7%) | |

| Benign lymphoid tissue | 1 (1.7%) | |

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number 8UL1TR000055. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

ACRONYMS

- EUS

Endoscopic Ultrasound

- FNA

Fine Needle aspiration

- S+

Syringe On; the suction-syringe with its stopcock closed still attached to the needle handle.

- S−

Syringe Off; the suction-syringe with its stopcock closed still disconnected from the needle handle.

- −

Minus (negative pressure)

Footnotes

Clinical Trials registration number: NCT01995474

REFERENCES

- 1.Dumonceau J-M, Polkowski M, Larghi A, Vilmann P, Giovannini M, Frossard J-L, et al. Indications, results, and clinical impact of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided sampling in gastroenterology: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2011 Oct 1;43(10):897–912. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewitt MJM, McPhail MJWM, Possamai LL, Dhar AA, Vlavianos PP, Monahan KJK. EUS-guided FNA for diagnosis of solid pancreatic neoplasms: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012 Feb 1;75(2) doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.049. 13-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mertz H, Gautam S. The learning curve for EUS-guided FNA of pancreatic cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004 Jan 1;59(1) doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02028-5. 5-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yusuf TET, Ho SS, Pavey DAD, Michael HH, Gress FGF. Retrospective analysis of the utility of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) in pancreatic masses, using a 22-gauge or 25-gauge needle system: a multicenter experience. Endoscopy. 2009 May 1;41(5):445–448. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song TJ, Kim JH, Lee SS, Eum JB, Moon SH, Park DH, et al. The prospective randomized, controlled trial of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration using 22G and 19G aspiration needles for solid pancreatic or peripancreatic masses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Aug;105(8):1739–1745. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klapman, Logrono, Dye, Waxman Clinical impact of on-site cytopathology interpretation on endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003 Jun 1;98(6) doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07472.x. 6-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wani S, Early D, Kunkel J, Leathersich A, Hovis CE, Hollander TG, et al. Diagnostic yield of malignancy during EUS-guided FNA of solid lesions with and without a stylet: a prospective, single blind, randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012 Aug;76(2):328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.03.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puri RR, Vilmann PP, Săftoiu AA, Skov BGB, Linnemann DD, Hassan HH, et al. Randomized controlled trial of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle sampling with or without suction for better cytological diagnosis. Audio, Transactions of the IRE Professional Group on. 2009 Jan 1;44(4):499–504. doi: 10.1080/00365520802647392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JK, Choi JH, Lee KH, Kim KM, Shin JU, Lee JK, et al. A prospective, comparative trial to optimize sampling techniques in EUS-guided FNA of solid pancreatic masses. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 Feb 21; doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savides TJ. Tricks for improving EUS-FNA accuracy and maximizing cellular yield. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009 Feb 1;69(2) doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.12.018. 0-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitsuhashi T, Ghafari S, Chang CY, Gu M. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of the pancreas: cytomorphological evaluation with emphasis on adequacy assessment, diagnostic criteria and contamination from the gastrointestinal tract. Cytopathology. 2006 Feb;17(1):34–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2006.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujii LL, Levy MJ. Pitfalls in EUS FNA. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2014 Jan;24(1):125–142. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gleeson FC, Kipp BR, Caudill JL, Clain JE, Clayton AC, Halling KC, et al. False positive endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration cytology: incidence and risk factors. Gut. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and British Society of Gastroenterology. 2010 May;59(5):586–593. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.187765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eloubeidi MA, Jhala D, Chhieng DC, Chen VK, Eltoum I, Vickers S, et al. Yield of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy in patients with suspected pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. Wiley Subscription Services, Inc., A Wiley Company. 2003 Oct 25;99(5):285–292. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kliment M, Urban O, Cegan M, Fojtik P, Falt P, Dvorackova J, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of pancreatic masses: the utility and impact on management of patients. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. Informa Healthcare Stockholm. 2010 Nov;45(11):1372–1379. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.503966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woolf KMW, Liang H, Sletten ZJ, Russell DK, Bonfiglio TA, Zhou Z. False-negative rate of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for pancreatic solid and cystic lesions with matched surgical resections as the gold standard: one institution's experience. Cancer cytopathology. 2013 Aug;121(8):449–458. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace MB, Kennedy T, Durkalski V, Eloubeidi MA, Etamad R, Matsuda K, et al. Randomized controlled trial of EUS-guided fine needle aspiration techniques for the detection of malignant lymphadenopathy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001 Oct;54(4):441–447. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.117764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Storch IM, Sussman DA, Jorda M, Ribeiro A. Evaluation of fine needle aspiration vs. fine needle capillary sampling on specimen quality and diagnostic accuracy in endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy. Acta Cytol. 2007 Nov;51(6):837–842. doi: 10.1159/000325857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bang JY, Ramesh J, Trevino J, Eloubeidi MA, Varadarajulu S. Objective assessment of an algorithmic approach to EUS-guided FNA and interventions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 May;77(5):739–744. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakai Y, Isayama H, Chang KJ, Yamamoto N, Hamada T, Uchino R, et al. Slow pull versus suction in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of pancreatic solid masses. Dig Dis Sci. Springer US. 2014 Jul;59(7):1578–1585. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-3019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polkowski M, Larghi A, Weynand B, Boustière C, Giovannini M, Pujol B, et al. Learning, techniques, and complications of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided sampling in gastroenterology: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Technical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2012:190–206. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wani S, Muthusamy VR, Komanduri S. EUS-guided tissue acquisition: an evidence-based approach (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2014 Dec;80(6):939.e7–959.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rastogi A, Wani S, Gupta N, Singh V, Gaddam S, Reddymasu S, et al. A prospective, single-blind, randomized, controlled trial of EUS-guided FNA with and without a stylet. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Jul;74(1):58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kudo T, Kawakami H, Hayashi T, Yasuda I, Mukai T, Inoue H, et al. High and low negative pressure suction techniques in EUS-guided fine-needle tissue acquisition by using 25-gauge needles: a multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014 Dec;80(6):1030–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iglesias-Garcia J, Dominguez-Munoz JE, Abdulkader I, Larino-Noia J, Eugenyeva E, Lozano-Leon A, et al. Influence of on-site cytopathology evaluation on the diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of solid pancreatic masses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Sep;106(9):1705–1710. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashi T, Ishiwatari H, Yoshida M, Ono M, Sato T, Miyanishi K, et al. Rapid on-site evaluation by endosonographer during endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for pancreatic solid masses. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Apr;28(4):656–663. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wani S, Mullady D, Early DS, Rastogi A, Collins B. Clinical impact of immediate on-site cytopathology (CyP) evaluation during endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of pancreatic mass: Interim analysis of a multicenter randomized con- trolled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:2. (Abstract supplement) [Google Scholar]