Abstract

A middle-aged female with metastatic melanoma was found to have hemoperitoneum after starting systemic therapy with the BRAF and MEK inhibitors dabrafenib and trametinib. Etiology proved to be bleeding from a known hepatic metastasis. The patient was managed conservatively and eventually resumed systemic therapy with ongoing response. This case serves to illustrate the possible deleterious effects of rapid tumor response after initiation of targeted systemic therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma.

Keywords: dabrafenib, trametinib, BRAF, MEK

In 2014, the Food and Drug Administration granted fast-track approval for combination blockade of the BRAF and MEK pathway in patients who have unresectable advanced melanoma with BRAF V600E, or V600K mutations. As compared with single-agent blockade, this combination improves response rates and prolongs progression-free and overall survival, with an acceptable rate of adverse events [1–3]. However, this treatment’s rapid induction of response introduces potential for novel problems related to rapid tumor necrosis within solid organs harboring metastases.

A 49-year-old female with a past medical history significant for Crohn’s disease noted an enlarging right cervical lymph node. Biopsy revealed this mass to be metastatic melanoma. No primary lesion was noted. Extent of disease evaluation for staging revealed no distant metastatic disease (Fig. 1A). The patient was treated surgically with a modified radical right neck dissection and right parotidectomy. Pathology confirmed the diagnosis of malignant melanoma (2.6 cm) involving a salivary gland and surrounding soft tissue along with nodal involvement (1 of 65 nodes, stage IIIC). Subsequent tumor analysis revealed the tumor possessed a V600E BRAF mutation. Post-operatively she was treated with adjuvant radiation therapy. Approximately 3 months after the neck dissection, follow-up imaging revealed metastatic progression involving her liver (Fig. 1B), accompanied by an elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase level. At this time, she began targeted therapy with dabrafenib and trametinib. After three doses the patient suddenly developed severe pain in the right upper abdomen, anemia (lowest hemoglobin during resultant hospitalization was 6.8 gm/dl; hemoglobin 5 days prior to admission was 11.5 gm/dl), and thrombocytopenia (platelet count 49,000/cmm from 260,000/cmm 5 days prior). A CT angiogram illustrated the known right liver lobe lesion with a vascular blush and surrounding hemoperitoneum (Fig. 1C). She was managed conservatively, targeted therapy was withheld, and the bleeding spontaneously stopped. Upon discharge from the hospital her combination therapy was restarted. She currently remains on combination targeted therapy with ongoing response in the liver (Fig. 1D).

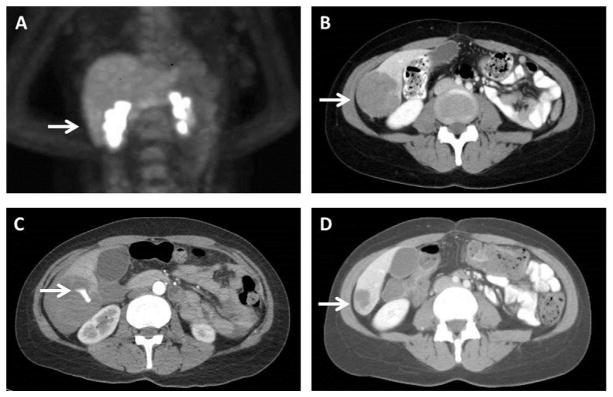

Fig. 1.

Images illustrating (A) the patient’s initial positron emission tomography (PET) scan for staging without evidence of hepatic metastasis (arrow indicating future area of metastasis), and computed tomography (CT) illustrating (B) the patient’s liver metastasis (arrow) prior to initiation of treatment, (C) active extravasation of contrast from the tumor (arrow) after three doses of combined targeted therapy, and (D) durable response (arrow) with re-initiation of therapy after resolution of the hemorrhagic event.

Although the combination of BRAF and MEK inhibitors is generally well-tolerated for first-line treatment of metastatic or unresectable BRAF V600 melanoma [1–3], this regimen can cause a wide range of adverse events. Pyrexia and chills are the most commonly reported events, and neutropenia is the most frequent grade 3 or 4 toxicity [2]. In general, bleeding has been associated with combination therapy and thrombocytopenia with dabrafenib and trametinib monotherapies [3,4].

In the case reported, the patient had an acute change in clinical status due to hepatic hemorrhage and resultant hemoperitoneum that temporally was associated with the start of her combination therapy. Citing the fact that spontaneous rupture of metastatic melanoma within the liver is rare [5], and noting our patient’s sustained durable response to combination therapy subsequent to this incident, we concluded that the patient’s hepatic metastatic disease exhibited a rapid clinical response to targeted therapy resulting in tumor necrosis and rupture. Massive hemoperitoneum has been reported in metastatic melanoma patients receiving the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib as early as 12 days after initiating treatment [6].

In our case, surgical evaluation was promptly obtained and the patient was monitored closely until her clinical condition stabilized. The patient’s anemia and thrombocytopenia responded appropriately to transfusions, and the observed thrombocytopenia was concluded to be secondary to bone marrow suppression from her systemic treatment as there was no evidence of on-going coagulopathy. Importantly, after the bleeding subsided, combination therapy was resumed, and the patient tolerated treatment well with continued durable response.

Rapid tumor response to a dabrafenib-trametinib combination has been reported in a patient with metastatic ameloblastoma [7], and this drug combination has also been linked to life-threatening bleeding in patients after resection of metastatic melanoma [8]. This rapid clinical response to targeted therapies has clinicians terming this the “Lazarus Syndrome” as the patient is resurrected from progressive, debilitating disease [9]. Such responses can be fraught with significant morbidity and lead to life-threatening sequelae.

Our case report is the first to show that rapid tumor response to combined targeted therapy can be problematic in patients with metastatic melanoma. Tumor necrosis in solid organs or near vital structures rapidly changes the anatomic environment and thereby may produce a life-threatening clinical situation requiring immediate surgical evaluation. Moving forward, clinicians should possess a heightened awareness to any acute clinical changes in patients with known solid-organ melanoma metastases after initiation of targeted therapies. Furthermore, a low threshold should exist to seek surgical advice in circumstances with suspected deleterious rapid response. The irony exists with targeted therapy, as it does with the immune checkpoint inhibitors ipilimumab and nivolumab, that we now must harbor concern about “overly vigorous antimelanoma responses” [10].

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants R01 CA189163 from the National Cancer Institute and by funding from the Amyx Foundation, Inc, (Boise, ID) and Alan and Brenda Borstein (Los Angeles, CA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: DCF received first-assist robotic training sponsored by Intuitive Surgical, Inc.; BWH is a consultant for Merck and Co., Inc., Bristol–Myers Squibb, and Genentech, Inc.; BJL has received fees from Intuitive Surgical, Inc.; BJL holds stock in Johnson and Johnson, Inc.; OH is a consultant for Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, and Bristol–Myers Squibb; OH is a speaker for Bristol–Myers Squibb, Genentech, and GlaxoSmithKline; OH conducts contracted research for AstraZeneca, Bristol–Myers Squibb, Celldex, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Immunocore, Incyte, Merck, Merck Serano, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Rinat, and Roche; MBF is a consultant for Genentech, Inc.; MBF is on the advisory board for Astellas Pharmaceuticals and Amgen, Inc., and Myriad Genetics, Inc.

References

- 1.Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:30–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1694–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib versus dabrafenib and placebo for Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma: A multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:444–451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60898-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waddell JA, Solimando DA., Jr Drug monographs: Dabrafenib and trametinib. Hosp Pharm. 2013;48:818–821. doi: 10.1310/hpj4810-818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nosaka T, Hiramatsu K, Nemoto T, et al. Ruptured hepatic metastases of cutaneous melanoma during treatment with vemurafenib: An autopsy case report. BMC Clin Pathol. 2015;15:15. doi: 10.1186/s12907-015-0015-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castellani E, Covarelli P, Boselli C, et al. Spontaneous splenic rupture in patient with metastatic melanoma treated with vemurafenib. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:155. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaye FJ, Ivey AM, Drane WE, et al. Clinical and radiographic response with combined BRAF-targeted therapy in stage 4 ameloblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:378. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee le M, Feun L, Tan Y. A case of intracranial hemorrhage caused by combined dabrafenib and trametinib therapy for metastatic melanoma. Am J Case Rep. 2014;15:441–443. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.890875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furmark L, Pavlick AC. BRAF Inhibitors and the “Lazarus Syndrome” —An update and perspective. Am J Hematol/Oncol. 2015;11:24–29. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapman PB, D’Angelo SP, Wolchok JD. Rapid eradication of a bulky melanoma mass with one dose of immunotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2073–2074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1501894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]