Abstract

Purpose

Updated estimates of adolescents’ receipt of sex education are needed to monitor changing access to information.

Methods

Using nationally representative data from the 2006–2010 and 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth, we estimated changes over time in adolescents’ receipt of sex education from formal sources and from parents and differentials in these trends by adolescents’ gender, race/ethnicity, age, and place of residence.

Results

Between 2006–2010 and 2011–2013, there were significant declines in adolescent females’ receipt of formal instruction about birth control (70% to 60%), saying no to sex (89% to 82%), sexually transmitted disease (94% to 90%), and HIV/AIDS (89% to 86%). There was a significant decline in males’ receipt of instruction about birth control (61% to 55%). Declines were concentrated among adolescents living in nonmetropolitan areas. The proportion of adolescents talking with their parents about sex education topics did not change significantly. Twenty-one percent of females and 35% of males did not receive instruction about methods of birth control from either formal sources or a parent.

Conclusions

Declines in receipt of formal sex education and low rates of parental communication may leave adolescents without instruction, particularly in nonmetropolitan areas. More effort is needed to understand this decline and to explore adolescents’ potential other sources of reproductive health information.

Keywords: Sex education, Sex information, Parent communication

Providing adolescents with sexual health information is an important means of promoting healthy sexual development and reducing negative outcomes of sexual behaviors [1–4]. National public health goals [5] and numerous medical and public health organizations [6,7] recommend that adolescents receive sex education on a range of topics. However, past research has found increasing gaps in sex education; analyses of data from the National Surveys of Family Growth (NSFG) indicate that from 1995 to 2006–2008, the proportion of U.S. teens who had received formal instruction about birth control methods declined (males, 81% to 62%; females, 87% to 70%) [8,9].

National public health goals call for increasing the share of adolescents receiving formal instruction about abstinence, birth control methods, and prevention of HIV/AIDS and STIs and increasing the proportion of teens talking with their parents about these same topics [5]. These goals also establish objectives for reducing differentials in the receipt of sex education by gender, race/ethnicity, and other sociodemographic characteristics.

This analysis examines recent changes in adolescents’ reports of receipt of formal sex education and instruction from parents, using nationally representative data from both females and males from the 2006–2010 and 2011–2013 NSFG. This extends previous work monitoring national trends in sex education since 1995 [8–11]. We test for differential patterns of receipt of instruction by adolescents’ sociodemographic characteristics and place of residence. We also consider how formal instruction and the informal sex education provided by parents supplement each other. These analyses are descriptive, with the objective of providing ongoing national monitoring needed to inform related research and policy.

Methods

Data

This analysis used data from the 2006–2010 and 2011–2013 NSFG, a continuous national probability household survey of women and men aged 15–44 years in the United States (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg.htm) [12]. The surveys used a multistage, stratified clustered sampling frame to collect interviews continuously from June 2006 to December 2010 and from June 2011 to June 2013. The National Center for Health Statistics Institutional Review Board approved data collection.

We limited the analyses to respondents aged 15–19 years at the time of the interview, resulting in samples of 2,284 and 1,037 females and 2,378 and 1,088 males in 2006–2010 and 2011–2013, respectively.

Measures

Formal instruction: in both surveys, respondents were asked “Before you were 18, did you ever have any formal instruction at school, church, a community center or some other place about” the following topics: “how to say no to sex,” “methods of birth control,” “sexually transmitted diseases,” and “how to prevent HIV/AIDS.” Additionally, in the 2011–2013 survey, respondents were also asked about formal instruction on “waiting until marriage to have sex,” “where to get birth control,” and “how to use a condom.” The survey added these latter topics to address concerns that the earlier survey’s measures did not provide adequate information about the specific instructional content.

Respondents answering that they had received instruction in a particular topic received follow-up questions about whether instruction occurred before the first vaginal intercourse.

Informal instruction from parents: respondents were asked whether they had talked with their parent or guardian about the following six topics before they were aged 18 years: “how to say no to sex,” “birth control methods,” “where to get birth control,” “how to use a condom,” “sexually transmitted diseases,” and “how to prevent HIV/AIDS.”

Analysis

To examine changes over time in adolescents’ receipt of formal and informal instruction, the 2006–2010 and 2011–2013 NSFG data sets were merged, and each period was weighted accordingly. For each period, we calculated the weighted prevalence of the receipt of formal instruction by topic, separately for male and female adolescents; additional topics of instruction measured in only the 2011–2013 survey were also examined. For each gender, simple logistic regressions were estimated to test for significant differences between the two periods in the prevalence of each topic by age (15–17 vs. 18–19), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic), household poverty status (<200% of poverty line vs. ≥200% of poverty), place of residence (central city, other metropolitan area, nonmetropolitan area), and religious attendance at age 14 years (often, sometimes, never); overall differences in receipt by gender were also tested.1 We also used simple logistic regression to test for significant differences between periods in the proportion of adolescents who had received instruction in each topic before the first sex and changes in the proportion of adolescents talking with their parents about each of the six reproductive health topics and differences by key demographic groups. Finally, we estimated the proportion of teens receiving instruction on each topic from both formal sources and parents, only one source, or not at all. All analyses accounted for the complex survey design of the NSFG data using the svy commands in Stata 13.0 [13], and we report only differences with a p value <5%.

Results

Sample characteristics

Among the weighted sample of respondents aged 15–19 years in 2006–2010 and 2011–2013, the majority were non-Hispanic white, aged 15–17 years and attended religious services often when they were aged 14 years (Table 1). About one-third resided in a central city, half in other metropolitan areas, and the remaining share in nonmetropolitan statistical areas. There was no significant change over time in any of these demographic traits for either gender. In contrast, the share of teens living in households with income <200% of the household poverty line increased significantly over time for both females and males.

Table 1.

Percentage distribution of respondents aged 15–19 years, 2006–2010 and 2011–2013 National Surveys of Family Growth

| Characteristic | Females

|

Males

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006–2010 (N =2,284) | 2011–2013 (N =1,037) | 2006–2010 (N =2,378) | 2011–2013 (N =1,088) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 59 | 53 | 60 | 53 |

| Hispanic | 18 | 22 | 19 | 22 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 16 | 16 | 15 | 16 |

| Other race | 6 | 8 | 6 | 8 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 15–17 | 56 | 59 | 61 | 58 |

| 18–19 | 44 | 41 | 39 | 42 |

| Residence | ||||

| Central city | 31 | 31 | 31 | 29 |

| Other metropolitan | 49 | 54 | 50 | 54 |

| Nonmetropolitan | 19 | 15 | 19 | 17 |

| Household Poverty | ||||

| <200% | 57 | 65a | 50 | 58a |

| ≥200% | 43 | 35a | 50 | 43a |

| Religiosity at Age 14 years | ||||

| Often | 53 | 53 | 50 | 47 |

| Sometimes | 31 | 30 | 33 | 36 |

| Never | 16 | 17 | 17 | 16 |

Refers to time. Significantly different from the previous period at p < .05.

Formal instruction

Trends by gender

Between 2006–2010 and 2011–2013, there were significant declines in adolescent females’ reports of the receipt of formal instruction about birth control (70% to 60%), saying no to sex (89% to 82%), sexually transmitted disease (STD, 94% to 90%), and HIV/AIDS (89% to 86%) (Table 2). There was a significant decline in males’ reports of instruction about birth control (61% to 55%). Both genders had significant increases in the share reporting formal instruction in saying no to sex without instruction about birth control (22% to 28% females, 29% to 35% males).

Table 2.

Percentage of females and males aged 15–19 years who had received formal instruction on specific sex education topics by age 18 years, by selected characteristics, 2006–2010 and 2011–2013

| Methods of birth control (BC) |

Say no to sex |

Say no to sex, no BC instruction |

STDs | HIV/AIDS | Wait to have sex |

Where to get BC |

Condom use |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| 2006 –2010 |

2011 –2013 |

2006 –2010 |

2011 –2013 |

2006 –2010 |

2011 –2013 |

2006 –2010 |

2011 –2013 |

2006 –2010 |

2011 –2013 |

2011 –2013 |

2011 –2013 |

2011 –2013 |

|

| Females | 70b | 60a | 89b | 82a | 22b | 28a | 94b | 90a | 89 | 86a | 76 | 53b | 50b |

| Race/ethnicityd | |||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white (ref) | 71 | 57a | 91 | 82a | 23 | 29 | 94 | 91 | 89 | 86 | 79 | 51 | 46 |

| Hispanic | 68 | 67 | 83c | 78 | 22 | 25 | 92 | 90 | 90 | 85 | 69c | 56 | 59c |

| Non-Hispanic black | 68 | 69c | 89 | 88 | 24 | 23 | 92 | 93 | 89 | 88 | 83 | 61 | 63c |

| Age, years | |||||||||||||

| 15–17 (Ref) | 64 | 53a | 88 | 84 | 27 | 36a | 93 | 90 | 88 | 86 | 79 | 48 | 44 |

| 18–19 | 78c | 72c | 89 | 80a | 16c | 18c | 95 | 90a | 90 | 85a | 73 | 60c | 60c |

| Religious attendance | |||||||||||||

| Often (ref) | 70 | 57a | 91 | 85a | 25 | 33 | 94 | 90 | 89 | 86 | 82 | 49 | 49 |

| Sometimes | 70 | 62 | 87 | 81 | 21 | 26 | 95 | 93 | 91 | 87 | 72c | 59c | 51 |

| Never | 74 | 67 | 85 | 75 | 16c | 19 | 92 | 88 | 88 | 82 | 68c | 56 | 53 |

| Household poverty | |||||||||||||

| <200% Poverty (ref) | 67 | 60 | 87 | 80a | 23 | 27 | 92 | 88 | 88 | 84 | 75 | 50 | 50 |

| ≥200% | 75c | 62a | 91c | 87c | 21 | 30a | 96c | 94 | 91 | 88 | 79 | 58 | 52 |

| Residence | |||||||||||||

| Central city (ref) | 70 | 70 | 89 | 86 | 23 | 24 | 93 | 91 | 88 | 89 | 74 | 64 | 65 |

| Other metropolitan | 71 | 59a,c | 87 | 82 | 21 | 29a | 93 | 93 | 89 | 87 | 79 | 49c | 47c |

| Nonmetropolitan | 71 | 48a,c | 92 | 78a | 23 | 35 | 96 | 81a | 91 | 75a,c | 70 | 44c | 33c |

| Males | 61 | 55a | 82 | 84 | 29 | 35a | 92 | 91 | 88 | 86 | 73 | 38 | 58 |

| Race/ethnicityd | |||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white (ref) | 62 | 57 | 85 | 87 | 30 | 34 | 92 | 91 | 88 | 86 | 75 | 35 | 54 |

| Hispanic | 59 | 55 | 77c | 77c | 27 | 32 | 91 | 94 | 87 | 88 | 64c | 43 | 64c |

| Non-Hispanic black | 53c | 46 | 79c | 79c | 34 | 41 | 90 | 90 | 86 | 84 | 82 | 39 | 61 |

| Age, years | |||||||||||||

| 15–17 (Ref) | 57 | 50a | 84 | 82 | 33 | 38 | 91 | 91 | 88 | 85 | 72 | 33 | 55 |

| 18–19 | 67c | 62c | 80 | 86a | 23c | 30 | 92 | 91 | 88 | 88 | 76 | 45c | 62 |

| Religious attendance | |||||||||||||

| Often (ref) | 58 | 50a | 84 | 83 | 32 | 38 | 91 | 99 | 86 | 83 | 79 | 34 | 54 |

| Sometimes | 64 | 59 | 83 | 84 | 28 | 33 | 93 | 96 | 91c | 91c | 68c | 40 | 63 |

| Never | 62 | 60c | 76c | 83 | 25 | 28c | 92 | 91 | 86 | 87 | 70c | 43 | 57 |

| Household poverty | |||||||||||||

| <200% Poverty (ref) | 55 | 51 | 80 | 81 | 32 | 36 | 89 | 89 | 85 | 83 | 74 | 34 | 58 |

| ≥200% | 66c | 60c | 85c | 87c | 26c | 33 | 94c | 94 | 90c | 90c | 73 | 42 | 58 |

| Residence | |||||||||||||

| Central city (ref) | 60 | 58 | 77 | 82 | 28 | 31 | 89 | 92 | 86 | 90 | 70 | 45 | 66 |

| Other metropolitan | 62 | 56 | 84c | 87 | 29 | 36 | 92 | 93 | 88 | 88 | 77 | 37 | 56c |

| Nonmetropolitan | 59 | 45* | 86c | 77a | 32 | 37 | 95c | 83a,c | 91 | 76a,c | 67 | 27c | 51c |

Ref =reference group; STD =sexually transmitted disease.

p < .06.

Refers to time. Significantly different from the previous period at p < .05.

Refers to gender. Significantly different between total males and total females at p < .05.

Refers to reference group. Significantly different from reference group at p < .05.

Non-Hispanic other not shown because of small sample size.

In 2006–2010, there were significant gender differences in multiple topics of formal instruction, but differential declines resulted in no significant differences by gender in 2011–2013 for the same topics. By 2011–2013, receipt of instruction about STDs or HIV/AIDS was most common (near 90% for each gender), and adolescents were less likely to receive instruction about birth control than about saying no to sex.

Trends by other demographics

Among girls, declines over time in instruction about saying no to sex and declines in instruction about birth control were concentrated among whites, with no significant changes among black or Hispanic girls. Significant declines between periods in instruction about how to say no to sex, STDs, and HIV/AIDS occurred only among girls aged 18–19 years and not their younger peers. In contrast, significant declines in instruction about birth control occurred only among the younger teens for both genders. Adolescents who reported the highest levels of religious attendance at age 14 years had significant declines in receipt of instruction about methods of birth control (both genders) and how to say no to sex (girls); there was no change in instruction among teens with less or no religious attendance. Among girls, there were declines in instruction about saying no to sex among those living in households with income <200%; in contrast, a decline in instruction about birth control occurred only among girls living in households with income ≥200%.

Both male and female adolescents living in nonmetropolitan statistical areas had significant declines in receipt of instruction in methods of birth control2, saying no to sex, STDs, and HIV/AIDS, while there were few declines among teens residing in central cities or other metropolitan areas (Table 2). The consistency of these declines for teens in nonmetropolitan areas across topics of instruction and gender is noteworthy, especially given the stability across other characteristics among males.

New measures

The additional survey items added in the 2011–2013 NSFG allowed measurement of topics of instruction with more specificity (final columns, Table 2). About three-quarters of both females and males reported formal instruction on waiting until marriage to have sex, close to the share reporting receipt of instruction about how to say no to sex. Girls were significantly more likely than boys to receive instruction about where to get birth control (53% vs. 38%), whereas boys were significantly more likely than girls to receive formal instruction on how to use a condom (50% females, 58% males). Overall, about one-quarter of teens reported not receiving instruction on any of these birth control topics.

Timing of formal instruction

The share of girls receiving instruction about how to say no to sex before the first sex declined significantly (78% to 70%), as did the share of boys receiving instruction about birth control methods before the first sex (52% to 43%; Table 3). There was no change over time in instruction about STDs or HIV/AIDS before the first sex. In 2011–2013, sexually experienced boys were significantly less likely than girls to receive instruction before the first sex about methods of birth control or where to get birth control.

Table 3.

Percentage of sexually experienced females and males aged 15–19 years who received formal instruction on specific sex education topics before the first intercourse, 2006–2010 and 2011–2013

| Topic of formal instruction | Females

|

Males

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 –2010 | 2011 –2013 | 2006 –2010 | 2011 –2013 | |

| Say no to sex | 78 | 70a | 69b | 68 |

| Methods of birth control | 62 | 57 | 52b | 43a,b |

| STDs | 78 | 78 | 80 | 76 |

| HIV/AIDS | 74 | 74 | 77 | 73 |

| Wait to have sex | NA | 68 | NA | 62 |

| Where to get birth control | NA | 46 | NA | 31b |

| How to use condoms | NA | 47 | NA | 54 |

NA =not applicable; STD =sexually transmitted disease.

Refers to time. Significantly different from the previous period at p < .05.

Refers to gender. Significantly different between total males and total females at p < .05.

Parents

Between 2006–2010 and 2011–2013, there was little change in the share of adolescents reporting talking with their parents about sexual and reproductive health topics. Of the six topics examined, only the proportion talking with their parents about how to use a condom increased (males 37% to 45%, females 30% to 36%, not shown). Given this general stability, we present only estimates for 2011–2013 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Percentage of females and males aged 15–19 years who talked with parents about specific sex education topics by age 18 years, by race/ethnicity, 2011–2013

| Say no | Methods of BC | Where to get BC | STDs | HIV | How to use a condom | None | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 63a | 52a | 40a | 58a | 47a | 36a | 22a |

| Non-Hispanic white (ref) | 63 | 55 | 45 | 55 | 44 | 33 | 24 |

| Hispanic | 65 | 52 | 40 | 67b | 52 | 46b | 18 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 66 | 50 | 37 | 66 | 57 | 45b | 17 |

| Males | 43 | 31 | 22 | 49 | 40 | 45 | 30 |

| Non-Hispanic white (ref) | 48 | 36 | 25 | 50 | 36 | 43 | 30 |

| Hispanic | 35b | 30 | 19 | 55 | 47b | 50 | 25 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 48 | 30 | 25 | 56 | 50b | 58b | 19b |

Non-Hispanic other not shown because of small sample size.

BC =birth control; Ref =reference group; STD =sexually transmitted disease.

Refers to gender. Significantly different between total males and total females at p < .05.

Refers to reference group. Significantly different from reference group at p <.05.

Overall, 22% of females and 30% of males did not talk with their parents about any of these topics. Among female adolescents, the most common topics discussed with parents were how to say no to sex, STDs, and birth control methods; among male adolescents, the most common topics discussed were STDs and how to use a condom. Boys were more likely than girls to talk with their parents about how to use a condom; for all the other topics, girls reported more parental communication than did boys.

For each of the six topics, there was little variation by age, place of residence, religiosity, or household income (not shown). Hispanic males (35%) were significantly less likely than their black (48%) or white (48%) peers to talk with their parents about saying no to sex, whereas white males (36%) were less likely to talk with their parents about HIV/AIDS than Hispanic (47%) or black (50%) males. Additionally, black males (58%) were more likely to talk with their parents about how to use a condom than were other young men (43% white, 50% Hispanic). Among females, the only significant differences by race/ethnicity were higher rates of talking about how to use a condom among His-panic (46%) and black (45%) than white teens (33%) and higher rates of talking about STDs among Hispanic (67%) than non-Hispanic white girls (53%).

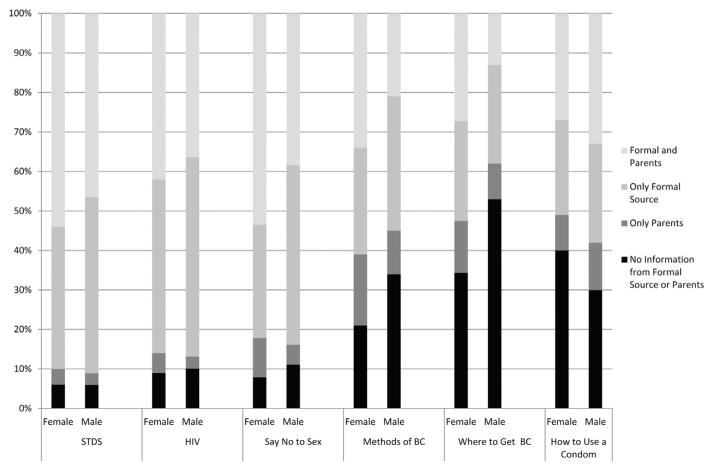

Combined sources of information

There was substantial variation by topic and gender in the extent to which parents and formal instruction supplemented or reinforced one another (Figure 1). Although many teens received instruction on specific topics from both schools and parents (ranging from a low of 13% of males in instruction on where to get birth control to 54% of girls on STDs), there was a substantial share of teens who reported receiving instruction on specific topics only in school (ranging from 25% to 45% across topics). In contrast, relatively few teens received instruction on a topic only from a parent. Teens were most likely not to receive instruction from either source about birth control methods generally (21% females, 34% males), where to get birth control (34% females, 53% males), or how to use a condom (40% females, 30% males).

Figure 1.

Reports of sex education instruction, by source, females and males aged 15–19 years, 2011–2013. BC =birth control; STD =sexually transmitted disease.

Discussion

The changes described in these analyses point to significant reductions in adolescents’ receipt of formal sex education, across topics addressing abstinence, birth control, and the prevention of HIV/AIDS and other STDs. This decline in formal instruction has been concentrated among girls, particularly non-Hispanic white teens and those living in nonmetropolitan areas. The lack of gender differences in formal instruction by 2011–2013 is a consequence of a shift away from formal instruction for girls, bringing them in line with the more limited instruction received by teen boys. Across both genders, many adolescents did not receive formal instruction on specific topics until after they became sexually active.

The declines in formal instruction about birth control identified in this study are part of a longer term trend. In 1995, 81% of adolescent males and 87% of adolescent females reported receiving formal instruction about birth control methods [8]; by 2011–2013, this had fallen to 55% of males and 60% of females. Similarly, the share of teens reporting formal instruction about “how to say no to sex” in these recent data is lower than previously estimated in the 1995 or 2002 NSFG. [8] In contrast, both genders had significant increases in receipt of formal instruction in saying no to sex without instruction about birth control, a proxy measure for abstinence-only education. Even with modest declines, 9 of 10 adolescents still report formal instruction about STDs. This instruction is generally limited; among high schools requiring instruction about STDs, only an average of 3.2 hours of instruction was required and may not occur as part of a broader sex education curriculum. [14].

These declines in formal instruction about birth control occurred despite increases in federal funding for teen pregnancy prevention programs and shifts in federal policy away from abstinence-only-until-marriage programs toward more comprehensive programs since 2009 [15]. Still, a relatively small number of youth are served by these federal programs, suggesting that their overall impact would be small [16,17]. In addition, significant funding for abstinence-only-until-marriage programs remains. In Fiscal Year 2016, Congress provided $85 million for abstinence-until-marriage programs3 [18]. At the state level, sex education requirements are still heavily weighted toward stressing abstinence until marriage [19]. The increase in abstinence-only education documented in this study shows the continued salience of this approach to sex education, despite criticism and concern from major public health and medical groups [6,7].

Findings from both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth Risk Behaviors Survey and their School Health Policies and Practices Study (SHPPS) generally corroborate the findings from the NSFG. The Youth Risk Behaviors Survey shows declines from 2001 to 2013 in the share of high school students receiving school-based instruction about HIV/AIDS (the only measure of school-based sex education available from this data source) [20]. SHPPs has documented reductions from 2000 to 2014 in the share of schools requiring instruction about a range of sexual health topics [14,21,22]. Unlike the NSFG, however, these data sources exclude out-of-school youth and do not permit examination of sociodemographic differences in adolescents’ exposure to sex education across a range of topics.

Among the sociodemographic differences of note found in this analysis are declines in formal sexeducation among teens residing in nonmetropolitan areas, encompassing both genders and many topics of instruction. (This occurred without contemporaneous declines in parental communication among rural teens.) These patterns are concerning as rural adolescents are a particularly vulnerable group, with higher rates of teen childbearing, lower rates of contraceptive use, and less access to sexual and reproductive health care services than their nonrural peers [23].

With fewer resources, rural school districts may be particularly vulnerable to the influence of national and state educational policies emphasizing high-stakes testing in some subjects which may leave reduced time and resources for other subjects such as health education [24]. Similarly, within overall health education, sexual health topics may be of reduced priority compared to other topics. For example, SHPPS data show that from 2000 to 2012, declines in the share of school districts with policies about teaching HIV or other STD prevention were paralleled by increases in districts requiring instruction about other health topics of increasing public health concern, such as suicide and violence4 [25]. Research is needed to understand how different subjects may compete for inclusion in the curriculum or classroom, given limited time and other resources.

In contrast to the declines in formal sex education, the NSFG data indicate that parents’ involvement in their teens’ sex education have not changed over the period examined here or compared to published estimates from the 2002 NSFG [11]. An exception was the increase in adolescents reporting that their parents talked with them about using condoms; it is unclear why this was the only topic with such increases. Parents did not fill the gaps in education when formal instruction was lacking. In particular, many adolescents did not receive instruction about birth control from either source. With levels below national public health goals and evidence that even when parental communication occurs, its quality may be low, enhanced efforts are needed to increase and improve parent–child communication about sexual health issues. [26].

Across both formal and informal instruction, this analysis documented significant variations by race/ethnicity. Non-Hispanic black and Hispanic adolescents were generally more likely to talk with their parents about condoms or STD/HIV prevention than their white peers. Similarly, nonwhite teens were more likely than others to receive formal instruction about how to use a condom. These patterns may reflect concern with the substantially higher rates of STDs and HIV among racial/ ethnic minority teens in the United States [27].

Also noteworthy are the differentials in formal instruction by household poverty level, especially among young men. Compounding these disparities, the share of teens residing in lower-income households increased about 15% during the period under study. The intersections of poverty, gender, race, and sexual health are numerous [28]. Poor teens are more likely to live in impoverished neighborhoods, with lower school quality and less access to health services, and to have higher rates of STDs, teen childbearing, and early onset of sexual activity [29]. Improving both formal and informal sex education requires not only increasing the share of low income teens receiving this instruction but developing approaches that are responsive to the contexts of adolescents’ lives.

The declines in formal sex education found in this study occurred contemporaneously with substantial declines in the teen pregnancy and birth rates in the United States [30]. Although the underlying drivers of the recent declines in teen pregnancy are not well understood, improvements in contraceptive use have been identified as an important proximate determinant [31]. Yet in a potential paradox, formal instruction about birth control methods and sex education generally has declined. A prior NSFG analysis found that health care providers also did not fill the gaps; only 1 in 10 of sexually experienced teens lacking birth control information from parents or schools talked with a health care provider about birth control [32]. It is possible that teens have turned to digital media, including the Internet and social networking sites, for information. The increased availability of Internet to teens, its ease of use, and anonymity for searching sensitive or stigmatized topics make it a likely source of sexual and reproductive health information [33]. In a 2015 national survey of teens aged 13–17 years, 92% of American teens reported going online daily [34]. In a 2008–2009 national survey, among all 7th–12th graders, more than half (55%) say they have ever looked up health information online [35]; we know of no recent study specifically measuring the frequency of use of digital media for sexual and reproductive health information. Further research is needed to document on how and to what extent teens access and use sexual and reproductive health information online, as well as evaluating the quality of this information. Online resources are often inaccurate and successfully navigating and evaluating competing sources of online information can be challenging [36]. Efforts to develop the scope and quality of online sex education may offer new opportunities to meet the sexual health needs of adolescents [37].

Despite these aggregate trends, individual-level analyses using the NSFG data have found that receipt of formal sex education is associated with healthier sexual behaviors and outcomes [3,4]. Evaluations of specific sex education programs, particularly those taking a more comprehensive approach, have also found evidence of impacts on teen pregnancy and related sexual behaviors [1,2]. Quality sex education has as its objectives much more than risk reduction and aims to promote healthy sexual development more generally [38]. It seems unlikely that adolescents’ nearly universal access to the Internet means that other sources of formal and informal instruction are no longer relevant.

Limitations

This study has several limitations common to prior studies using the NSFG (for a fuller discussion, see Lindberg et al. 2006 [8]). A central limitation is that the available measures of sex education measured provide no information about the quality or quantity of this instruction and few details about its content. Additionally, there is no information about prevalence or changes over time in other important sex education topics such as puberty, dating and relationships, or sexual decision-making skills.

The NSFG provides no information on the location of the formal instruction; the survey items ask about instruction received in “school, church, or a community center or some other place.” New data collection should consider how formal instruction outside schools may be supplementing or replacing school-based sex education. In addition, adding survey items that measure sources of information more broadly, including the use of digital media, could fill a substantial gap in the literature.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

This study documents recent declines in adolescents’ receipt of formal sex education about a range of topics. Parents do not fill these gaps. Further efforts to increase access to comprehensive reproductive health information are warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lawrence Finer, Kathryn Kost and John Santelli for reviewing and commenting on this manuscript.

Funding Sources

This research was supported by a grant from an anonymous donor. Additional support was provided by the Guttmacher Center for Population Research Innovation and Dissemination (National Institutes of Health grant 5 R24 HD074034).

Footnotes

Within each period, we also tested for differences between demographic groups within each gender; these results are presented but not discussed as the primary focus was on change over time.

The change over time for instruction about methods of birth control for males was marginally significant (p =.055).

Sometimes now referred to as “risk-avoidance” programs.

SHPPS does not provide information about the school location to allow investigation of variation between rural and non-rural schools.

Disclaimer: The conclusions presented are those solely of the authors.

References

- 1.Goesling B, Colman S, Trenholm C, et al. Programs to reduce teen pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, and associated sexual risk behaviors: A systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chin H, Sipe T, Elder R, et al. The effectiveness of group-based comprehensive risk-reduction and abstinence education interventions to prevent or reduce the risk of adolescent pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus, and sexually transmitted infections: Two systematic reviews for the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:272–94. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindberg LD, Maddow-Zimet I. Consequences of sex education on teen and young adult sexual behaviors and outcomes. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:332–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohler PK, Manhart LE, Lafferty WE. Abstinence-only and comprehensive sex education and the initiation of sexual activity and teen pregnancy. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42:344–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Academy of Pediatrics: Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health and Committee on Adolescence. Sexuality education for children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2001;108:498–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santelli J, Ott M, Lyon M, et al. Abstinence-only education policies and programs: A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:83–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindberg LD, Santelli J, Singh S. Changes in formal sex education: 1995–2002. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38:182–9. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.182.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez G, Abma J, Copen C. NCHS data brief. No. 44. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. Educating teenagers about sex in the United States. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindberg LD, Ku L, Sonenstein F. Adolescents’ reports of reproductive health education, 1988 and 1995. Fam Plann Perspect. 2000;32:220–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robert A, Sonenstein F. Adolescents’ reports of communication with their parents about sexually transmitted diseases and birth control: 1988, 1995, and 2002. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:532–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed December 10, 2010];Public use data file documentation 2006–2010, user’s guide [Online] Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nsfg/NSFG_2006-2010_UserGuide_MainText.pdf.

- 13.StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 13 [Computer software] College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed October 14, 2015];Results from the School Health Policies and Practices study 2014 [Online] Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/shpps/pdf/shpps-508-final_101315.pdf.

- 15.Boonstra HD. Sex education: Another big step forward- and a step back. Guttmacher Policy Rev. 2010;13:27–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Office of Adolescent Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed July 1, 2015];HHS Office of Adolescent Health’s Teen Pregnancy Prevention [Online] Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/oah-initiatives/teen_pregnancy/about/Assets/tpp-overview-brochure.pdf.

- 17.Family and Youth Services Bureau, Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention Program. [Accessed December 1, 2015];Personal Responsibility Education Program. Available at: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/fysb/prep_congressional_pm_brief_20150626.pdf.

- 18.SIECUS. [Accessed February 1, 2016];Congressional Sex Ed Wrap Up [Online] 2015 Available at: http://www.siecus.org.

- 19.Guttmacher Institute. [Accessed July 1, 2015];State policies in brief as of December 1, 2015: Sex and HIV Education [Online] Available at: http://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_SE.pdf.

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Adolescent and School Health. [Accessed July 1, 2015];Trends in the Prevalence of Sexual Behaviors and HIV Testing, National YRBS: 1991–2013 [Online] Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trends/us_sexual_trend_yrbs.pdf.

- 21.Kann L, Brener ND, Allesnworth DD. Health Education: Results from the School Health Policies and Programs Study 2000. J Sch Health. 2001;71:251–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2001.tb03504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kann L, Brener ND, Wechsler H. Overview and summary: School Health Policies and Programs Study 2006. J Sch Health. 2007;77:385–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng A, Kaye K. Sex in the (non) city: Teen childbearing in rural America. Washington, DC: The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Au W. High-stakes testing and curricular control: A qualitative metasynthesis. Educ Res. 2007;36:258–67. [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Centers for Disease Control. [Accessed July 1, 2015];Results from the School Health Policies and Practices Study, 2012 [Online] Available at: http http://www.grants.gov/view-opportunity.html?oppId=271309.

- 26.Martino S, Elliott M, Corona R, et al. Beyond the “big talk”: The roles of breadth and repetition in parent-adolescent communication about sexual topics. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e612–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed July 1, 2015];STDs in racial and ethnic minorities [Online] Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats14/minorities.htm.

- 28.Weber L, Parra-Medina D. Intersectionality and women’s health: Charting a path to eliminating health disparities. Adv Gend Res. 2003;7:181–230. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schalet AT, Santelli JS, Russell ST, et al. Invited commentary: Broadening the evidence for adolescent sexual and reproductive health and education in the United States. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43:1595–610. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0178-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kost K, Henshaw S. US teenage pregnancies, births and abortions, 2010: National and state trends by age, race and ethnicity. New York, NY: Guttmacher Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boonstra HD. What is behind the declines in teen pregnancy? Guttmacher Policy Rev. 2014;(No. 14):15–21. Available at: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/gpr/17/3/gpr170315.html.

- 32.Donaldson A, Lindberg LD, Ellen J, Marcell A. Receipt of sexual health information from parents, teachers, and healthcare providers by sexually experienced U.S. adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:235–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon L, Daneback K. Adolescents’ use of the internet for sex education: A thematic and critical review of the literature. Int J Sex Health. 2013;25:305–19. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lenhar A, Duggan M, Perrin A, et al. Teens, social media & technology overview 2015. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rideout VJ, Foehr UG, Roberts DF. Generation M2: Media in the lives of 8-to 18-year-olds. Menlo Park, CA: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buhi ER, Daley EM, Oberne A, et al. Quality and accuracy of sexual health information web sites visited by young people. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:206–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strasburger VC, Brown SS. Sex education in the 21st century. JAMA. 2014;312:125–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Future of Sex Education Initiative. [Accessed July 1, 2015];National Sexuality Education Standards: Core content and skills, K-12 [Online] Available at: http://www.futureofsexed.org/documents/josh-fose-standards-web.pdf.