Abstract

Cancer immunotherapy using antigen-specific T cells has broad therapeutic potential. Chimeric antigen receptors and bispecific antibodies can redirect T cells to kill tumors without human leukocyte antigens (HLA) restriction. Key determinants of clinical potential include the choice of target antigen, antibody specificity, antibody affinity, tumor accessibility, T cell persistence, and tumor immune evasion. For pediatric cancers, additional constraints include their propensity for bulky metastatic disease and the concern for late toxicities from treatment. Nonetheless, the recent preclinical and clinical developments of these T cell based therapies are highly encouraging.

Keywords: bispecific antibodies, chimeric antigen receptors, immunotherapy, pediatric oncology, T cells

Introduction

The late nineteenth century witnessed the birth of cancer immunotherapy when Dr. William Coley treated cancer patients with mixtures of heat-killed streptococcal organisms and Serratia marcescens, called “Coley’s toxin”, based on his observation of tumor regression following erysipelas in patients with inoperable sarcomas [1]. Supplanted by radiotherapy throughout the early twentieth century, immunotherapy did not gain momentum until the 1950s when the concept of cancer immunosurveillance was put forward by Drs. Burnet and Thomas, and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant for leukemia was first performed by Dr. E. Thomas[2-4]. Cancer therapeutics continued to be dominated by intensive radiotherapy and chemotherapy, designed to match the unrelenting recurrences and aggressiveness of metastatic solid tumors. Cancer immunotherapy was not an accepted modality until the 1990s, upon the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of monoclonal antibodies. Since then, the concepts of “cancer immunosurveillance” and “cancer immunoediting” have shaped the development of cancer immunotherapy. Over the past two decades, a variety of clinical strategies including adoptive T cell therapies, cancer vaccines, and monoclonal antibodies have emerged and continually optimized following their initial clinical successes. However, these clinical strategies have only been sporadically applied in pediatric oncology. Recent successes in treating refractory cancers by using T cells redirected by chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) or by bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) have energized the field.

Immunosurveillance and Immunoediting

To better understand how host immunity can target malignancy, one must evaluate how immune cells and tumor cells interact. The endogenous immune system can recognize malignant transformation because of its accompanying neo-antigens. However, cancer cells quickly evolve evasive or immune-suppressive mechanisms to avoid detection and/or eradication. This process of cancer “immunosurvelliance” and “immunoediting” has been summarized into three sequential phases; elimination, equilibrium, and escape [5]. During the “elimination phase”, both innate and adaptive immune effectors combine to control the cancer growth. The innate immune cells such as macrophages, natural killer (NK), NK-T, and dendritic cells, cooperate to recognize and eliminate the transformed cells. Through their Fc receptors, they lyse or phagocytose tumor cells in the presence of anti-tumor antibodies. The professional antigen-presenting cells prime the CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells in the adaptive immune system. When CD4(+) cells engage the HLA-class II-peptide complex, they secrete cytokines such as interferon (INF)-γ and interleukins (e.g. IL-2) to orchestrate other effectors (including B lymphocytes) for an optimal anti-tumor response. CD8(+) T cells recognize tumor cells through tumor peptides presented on the human HLA-class I antigen, injecting their granzymes and perforins to kill. Rare cancer cell mutants with inherent or acquired capacities to evade the immune system can survive, and the tumor enters the “equilibrium phase”, where the rate of tumor growth is equal to the rate of tumor elimination. Finally, in the “escape phase”, additional tumor cell variants can completely escape recognition by the adaptive immune system. Many mechanisms can facilitate this escape, including the loss of HLA or the tumor antigen from the tumor cell surface, defects in tumor antigen processing, altered tumor microenvironment that is T-cell suppressive by recruiting regulatory T cells (Tregs) [6], myeloid-derived suppressor cells [7], or tumor associated M2 macrophages [8]. To combat this tumor “escape”, cancer biologists have recently focused on releasing the brake at immune checkpoints (e.g. CTLA4, PD1, PDL1) [9, 10]. The clinical potential of such manipulations assumes a preexisting tumor-specific T cell immunity. Unfortunately, if the tumor downregulates their HLA or target, or if the clonal frequency of these T cells are low (especially after immunosuppressive chemotherapy or radiation therapy), removing the brakes may not be adequate. If the preexisting immunity is not tumor-specific, autoimmune complications are expected. To overcome these limitations, CARs and BsAbs can provide powerful platforms to engage T cells for robust anti-tumor responses. The characteristics of these two platforms are the focus of this review.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells

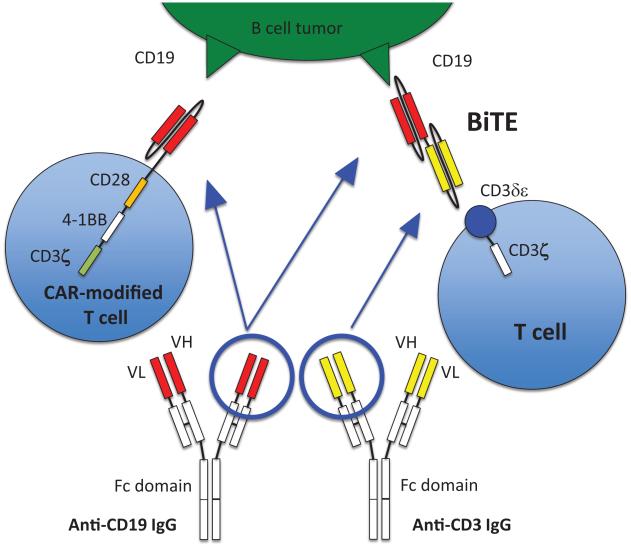

CARs are genetically engineered receptors that redirect T cells to a chosen tumor antigen. CARs usually consist of three domains: an extracellular antigen-binding domain, a transmembrane domain, and at least one intracellular signal transduction domain. They are genetically inserted into T cells using viral vectors, DNA transposons, or RNA transfection. When CARs bind to tumor antigen, the intracellular signaling domain is activated and the tumoricidal process by T cells is initiated. First generation CAR-modified T cells (CAR T cells) carrying a single activation domain consisting of either CD3-ζchain or FcεRIγ did not show significant efficacy in clinical trials because many tumor cells lack costimulatory ligands [11], although a phase 1 study of anti-GD2 CAR T cells in neuroblastoma showed objective clinical effects including complete remission in 3 patients.[12, 13]. The second generation CAR T cells contain an additional costimulatory sequence such as CD28 or CD137 (4-1BB), with improvement in T cell proliferation and survival in both preclinical and clinical settings [14-16]. Several third generation CAR T cells which carry two costimulatory sequences in tandem (e.g. CD28 and CD137) have also been tested [17-19] (Fig.1). While the current paradigm of CAR technology is focused on driving T cells to the tumor, recent pre-clinical studies of cellular cargos (e.g. potent immunostimulatory agents such as IL-12) suggest additional strategies in arming T cells to overcome the immuno-suppressive tumor microenvironment are feasible [20].

Figure 1.

Anti-CD19 CAR T cell (the third generation) recognizes CD19 antigen on a tumor cell via an anti-CD19 single chain Fv (scFv) binding domain. Anti-CD19 × anti-CD3 BiTE® is composed of two scFvs joined in tandem, i.e. anti-CD19 scFv and anti-CD3 scFv, recognizing CD19 on tumor cells and CD3 on T cells.

Bispecific antibody (BsAb)

BsAbs are antibodies with dual specificities; the first specificity against a tumor antigen, and the second specificity for an activator on immune effectors (e.g. CD3 on T cells). When activated through CD3, cytotoxic T cells inject perforin and granzyme B into target cells to kill. First-generation BsAbs were IgG-shaped molecules produced by fusing two different hybridomas, each directed at a different target [21, 22]. With the advances in protein engineering and recombinant DNA technologies, such as the packaging of the binding domains of the variable domains (VH and VL) of an IgG into a smaller single chain viable fragment (scFv), second-generation BsAbs are now possible, exploiting a variety of formats with increasing numbers of variable domains, specialized Fc forms, and novel functionalities [23, 24]. Bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE®) antibodies have two scFvs joined together as a single polypeptide chain in tandem, one scFv engaging tumor cells and the other scFv engaging CD3 on T cells (Fig.1). Univalent binding to CD3 without crosslinking to avoid nonspecific T cell activation is the driving principle behind the BiTE® and other engineered antibody platforms [25, 26], although a IgG-scFv platform was recently constructed to have low nonspecific T cell activation despite its bivalency [27]. It is of importance, though it remains to be generalized, that BsAbs can even redirect regulatory T cells (Treg) to kill tumor cells [28]. Unlike CAR T cells, BiTE®-activated T cells may be less susceptible to the inhibition by Treg [29, 30].

Selection of tumor targets and antibody affinity

One of the critical decisions in CAR T cell or BsAb strategy is the selection of the target antigen. Ideally it should have high expression on tumor cells, including tumor stem lines, and limited expression on normal cells. CAR T cells was shown to be more potent than BiTE®-redirected T cells when the target antigen density was low [31], likely due to BiTE® being monovalent. For CAR T cells, tumor engagement is likely multivalent, and tumor lysis did not correlate with the antigen-binding affinity [32-34]. For BiTE® platforms, increasing affinity enhanced anti-tumor effects in preclinical studies [35]. In contrast to the monovalent BiTE®, bivalent BsAbs can bind more avidly to the tumor cells to exert higher lytic potency even when target antigen is low [27, 36]. However, enhanced potency at low antigen density can also be a clinical risk. In a Phase 1 study using the third generation HER2 CAR T cells for metastatic HER2(+) cancer, a patient died from respiratory distress, a complication ascribed to T cells recognizing the low levels of HER2 in the lung [37]. Unless the cross-reactivity is restricted to non-essential organs, such sequelae could be serious. An example of non-essential tissue is the CD19(+) B cell population - when destroyed by CD19-directed CAR T cells, agammaglobulinemia develops in patients. Nevertheless, this condition is correctable by gamma globulin replacements. In order to reduce lethal cross-reactivities with critical organs, decreasing the T cell dose and/or the number of costimulatory sequences have been tried. Furthermore, a suicide gene system exploiting thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) or drug inducible caspase-9, can also be used to eliminate unwanted CAR T cells (NCT00182650, NCT01822652, NCT01953900).

Access of CAR T cells and BsAbs to tumor

Quantitative in vivo delivery of therapeutic agents to the target is another critical determinant of clinical efficacy. Solid cancers, especially bulky tumors, have mechanical barriers to intravenous therapies because of their disorganized vascularization and stiff tissue structure [38]. Most CAR T cells are infused intravenously with blood, bone marrow and lymph nodes being most accessible after intravenous injection. Hence, the efficacy is seen with hematogenous cancers, whereas the clinical potential for eradicating solid tumors is still uncertain [11, 13, 33]. To enhance T cell homing into the tumor, additional receptors such as chemokine/cytokine receptors (e.g. CXCR2 (CXCL1 receptor), CCR4 (CCL17 receptor)), or lymphotactin have been introduced into CAR T cells with some preclinical success [39-42].

BiTE® can penetrate into solid tumors because of their small size (about 60 kDa) and they redirect tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and even Tregs to kill tumor cells [28]. Larger BsAbs (160 kDa to 210 kDa) have also been successful in penetrating solid tumors in preclinical models [27, 36, 43, 44]. Compartmental administration can also overcome the difficulties in drug delivery to the tumors. For example, catumaxomab is administered intraperitoneally for treating malignant ascites [45-47], and rM28, a recombinant BsAb directed against high molecular weight melanoma-associated antigen and CD28 [48], is administered intratumorally against malignant melanoma.

Persistence of CAR T cells and BsAbs in vivo

Unlike BsAbs which can be administered in repeated doses over months, persistence of CAR T cells is essential especially in solid tumor because these cells are intended to last for years. Initial studies of CAR T cells documented their disappearance from peripheral blood within two to three weeks after infusion, despite their presence when assayed by PCR techniques [49]. The current generation of CAR T cells has improved persistence up to 11 months by flow cytometry, and 2 years by PCR as a result of lymphodepleting chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide +/− fludarabine) before CAR T cell infusion [50-54]. However, intense preconditioning increases the risk of infection and major organ damage including the heart, liver, and kidney, both in the short-term and the long-term. This could be particularly problematic for prior treated patients with relapsed or refractory disease. A relatively low dose of cytoreduction chemotherapy was given in a recent clinical study and it was tolerable [52]. In pre-clinical studies, T cell pre-selection [55, 56] and resistance to Tregs [56-59] have been investigated. In T cell pre-selection, early differentiation markers are used to isolate naïve CD8(+) T cells that will persist longer in vivo, and have superior anti-tumor immunity when compared to effector memory CD8(+) T cells [55, 56]. Through the activation of the Akt pathway, T cells can be prevented from forming Tregs or can be made insensitive to Tregs [56-59].

The serum half-life of BiTE® antibodies is measured in hours because of their small size. Various strategies have been adopted to maintain their therapeutic serum level. Blinatumomab (half-life 1.25 hours [60]) and MT110, an anti-epithelial cell adhesion molecule BiTE®, (half-life 4.5 hours [61]) were administered by continuous intravenous infusion over 4 weeks. Subcutaneous administration of MT112 (anti-prostate-specific membrane antigen BiTE®) as a depot for slow release for prostate cancer was also tested in pre-clinical studies [62]. Larger size BsAbs using a multimerization platform [63], or those built like an IgG [27, 44] will have longer serum half-lives, although toxicity may also increase. Clearly, treatment cycles of BsAbs could also be repeated to achieve their maximal clinical benefit.

Ease of use, quality control and accessibility of care

Looking ahead, accessibility of care can be a limiting step for drug acceptance. CAR T cell infusion is a personalized therapy. The process from autologous T cell collection, in vitro stimulation, CAR gene viral transduction, continual in vitro expansion, to infusion of CAR T cells takes an average of 7 to 11 days [50-52, 64] and according to Citigroup estimates, the cost per patient could be substantial [65]. Since cells have finite shelf-lives, they may be difficult to distribute across the continents. At present, such treatments are performed only at comprehensive medical centers with sophisticated laboratories staffed with personnel well trained in cytotherapy techniques of autologous T cell proliferation and T cell gene modification. An active effort both academically and commercially to set up centralized cell processing and distribution logistics will help increase acceptance by the health care system.

Building on the successes of monoclonal antibody therapies, BsAbs take advantage of their standardized manufacturing methods and quality control, as well as the protocols on how these drugs are administered. For diseases with high prevalence, BsAbs have improved chances of acceptance by patients and health care systems even if they have to be administered weekly or subcutaneously, since they can be given in an outpatient clinic and their cost can be less than CAR T cells [66].

Cytokine-release syndrome (CRS) is a concern for both CAR T cells and BsAbs, since it may require critical care. Recently, standardized treatment algorithm for the management of CRS has been established in a multi-institutional group [67], which in turn should result in a broader acceptance of these modalities in the medical community. Since the severity of CRS after CAR T cell infusions correlates with tumor burden, a more intensive pre-conditioning chemotherapy could be used to reduce the disease burden [52]. In the final analysis, efficacy, cost and toxicity will determine the future of either one of these T cell retargeting strategies.

Clinical Trials

As of January, 2015, at least 78 clinical trials using CAR T cells targeting 23 different antigens (Table I) and 42 clinical trials using 15 different types of BsAbs (Table II) have been registered to clinicaltrials.gov. Among CAR T cells, nearly half of the trials focused on CD19, and over 60% of them were designed for patients with hematological malignancies or lymphomas. Clinical studies have shown benefit among patients with B-lineage malignancies [50, 52], and their combinations with IL-2 or with dual specific T cells (e.g. EBV) have been tested (Table I). CAR T cells have also been tested in pediatric cancers (highlighted in Table I). Phase 1 clinical trials of CD19 CAR T cells in adult and pediatric patients with B cell-lineage malignancies showed safety and significant anti-tumor effects; 70-90% of patients have achieved complete remission (CR) 1 month after the CAR T cell infusion [51, 52]. Severe cytokine-release syndrome occurred in 14-27% of the patients, and they did respond to treatment with tocilizumab, a humanized anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody (NCT01626495, NCT01029366, NCT01593696)[50, 52].

Table I.

Clinical trials of CARs (Pediatric studies highlighted in grey) (as of Jan. 2015)

| CAR and target | Tumor type | Phase | Clinical trial | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD19 CAR (1st vs 2nd) | CD19+ leukemia, B-cell NHL | 1 | NCT00586391 | Active, No recruit |

| CD19 CAR (1st vs 2nd 4-1BB) | CD19+ leukemia, B-cell NHL | 1 | NCT01029366 | Completed |

| CD19 CAR | Relapsed or Refractory CD19+ CLL | 2 | NCT01747486 | Completed |

| CD19 CAR | Relapsed or Refractory B-cell NHL | 1 | NCT01840566 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR | Relapsed or Refractory B-cell NHL | 1, 2 | NCT02134262 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR | Relapsed or Refractory CD19+ leukemia, B-cell NHL | 1, 2 | NCT01865617 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR | CD19+ leukemia, B-cell NHL post-HSCT | 1 | NCT01497184 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR | Relapsed CD19+ ALL (1-26 years old) | 1 | NCT01683279 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR | Relapsed or Refractory CD19+ ALL (up to 26 years old) | 1 | NCT01860937 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR | CD19+ leukemia, B-cell NHL (1-30 years old) | 1 | NCT01593696 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR | Relapsed or Refractory CD19+ mantle cell lymphoma | 1, 2 | NCT02081937 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR 2nd 28 | CD19+ leukemia, B-cell NHL post-HSCT | 1 | NCT02050347 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR 2nd 4-1BB | Relapsed or Refractory CD19+ ALL | 2 | NCT02030847 | Active, No recruit |

| CD19 CAR 2nd 4-1BB | Relapsed or Refractory B-cell NHL | 2 | NCT02030834 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR 2nd 4-1BB | Relapsed or Refractory CD19+ leukemia, B-cell NHL | -- | NCT01864889 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR 2nd 4-1BB | Relapsed or Refractory CD19+ leukemia, B-cell NHL (1-24years old) | 1 | NCT01626495 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR 2nd 4-1BB expressing | Relapsed or Refractory CD19+ CLL (1-26 years old) | 1, 2 | NCT02028455 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR (2nd 28 vs 4-1BB) | CD19+ ALL | 1 | NCT01044069 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR (2nd 28 vs 4-1BB) | Relapsed or Refractory CD19+ CLL, B Cell NHL | 1, 2 | NCT00466531 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR (2nd 28 vs 28 and 4-1BB) | Relapsed or Refractory CD19+ CLL, B Cell NHL | 1 | NCT01853631 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR 3rd (28 and 4-1BB) | Relapsed or Refractory CD19+ leukemia, B-cell NHL | 1, 2 | NCT02132624 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR 3rd (28 and 4-1BB) | Relapsed or Refractory CD19+ ALL | 1 | NCT02186860 | Not yet recruiting |

| CD19 CAR + IL-2 | CD19+ leukemia, B-cell NHL | 1, 2 | NCT00924326 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR + IL-2 | B-cell NHL | 1 | NCT01493453 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR +/− IL-2 | CD19+ leukemia, B-cell NHL post-HSCT | 1 | NCT00968760 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR allo T cells | CD19+ leukemia, B-cell NHL recurrent or persistent after HSCT | 1 | NCT01087294 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR, EBV T cells | CD19+ CLL, B-cell NHL | 1 | NCT00709033 | Active, No recruit |

| CD19 CAR, allo EBV T cells | CD19+ ALL post-HSCT | 1 | NCT01430390 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR, EBV T cells + EBV cell | CD19+ leukemia, B-cell NHL post-HSCT | 1, 2 | NCT01195480 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR, adeno virus/EBV/CMV T | CD19+ leukemia, B-cell NHL post HSCT | 1. 2 | NCT00840853 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR, allo CMV or EBV T cells | CD19+ leukemia, B-cell NHL post-HSCT | 1, 2 | NCT01475058 | Active, No recruit |

| CD19 CAR, CM T cells | CD19+ leukemia, B-cell NHL post-HSCT | 1, 2 | NCT01318317 | Active, No recruit |

| CD19 CAR + HyTK (selection/suicide) | B-cell NHL (16-70 years old) | 1 | NCT00182650 | Completed |

| CD19 CAR, self-withdrawal mechanism | B-cell NHL | 1, 2 | NCT02247609 | Recruiting |

| CD19 CAR, TCRζ 4-1BB | HL | pilot | NCT02277522 | Not yet recruiting |

| CD19 CAR, EGFRt | CD19+ leukemia, | 1 | NCT02146924 | Recruiting |

| CD20 CAR + IL-2 | Relapsed or Refractory B-cell NHL | 1 | NCT00012207 | Completed |

| CD20 CAR 2nd 4-1BB vs TCR zeta | Relapsed or Refractory CD20+ leukemia | -- | NCT01735604 | Recruiting |

| CD20 CAR 3rd + IL-2 | CD20+ leukemia, B-cell NHL | 1 | NCT00621452 | Completed |

| CD22 CAR | CD22+ ALL, NHL, follicular, large cell lymphoma (1-30 years old) | 1 | NCT02315612 | Recruiting |

| CD30 CAR | CD30 + NHL, CD30+ HL (16-80 years old) | 1, 2 | NCT02259556 | Recruiting |

| CD30 CAR 2nd | CD30 + NHL, CD30+ HL | 1 | NCT01316146 | Recruiting |

| CD30 CAR, EBV T cells | CD30 + NHL, CD30+ HL | 1 | NCT01192464 | Recruiting |

| CD30 CAR, self-withdrawal mechanism | CD30+ HL, anaplastic large cell lymphoma | 1, 2 | NCT02274584 | Recruiting |

| CD33 CAR 2nd 137 | CD33+ AML (5-90 years old) | 1, 2 | NCT01864902 | Recruiting |

| CD123 CAR 2nd 28 | Relapsed or Refractory CD123+ AML | 1 | NCT02159495 | Not yet recruiting |

| CD138 CAR 2nd 4-1BB | CD138 + multiple myeloma | 1, 2 | NCT01886976 | Recruiting |

| LewisY CAR 2nd 28 | LewisY+ myeloma, AML or high risk MDS | 1 | NCT01716364 | Unknown |

| Kappa CAR 2nd 28 | CLL, recurrent or Refractory B-cell NHL, multiple myeloma | 1 | NCT00881920 | Recruiting |

| NKG2D-Ligands CAR | AML, MDS, multiple myeloma | 1 | NCT02203825 | Not yet recruiting |

| HER-2 CAR 2nd 28 | HER-2+ sarcoma | 1 | NCT00902044 | Recruiting |

| HER-2 CAR 2nd 4-1BB | HER-2+ solid tumors | 1, 2 | NCT01935843 | Recruiting |

| HER-2 CAR, 3rd 28 and 4-1BB + IL-2 | HER-2+ metastatic cancer | 1 | NCT00924287 | Terminated |

| HER-2 CAR, CMV T cells | HER-2+ glioblastoma | 1,2 | NCT01109095 | Recruiting |

| HER-2 CAR, TGFbeta DNR EBV T cells | HER-2+ metastatic or advanced stage cancer | 1 | NCT00889954 | Recruiting |

| GD2 CAR, EBV T cells | Relapsed or Refractory neuroblastoma | 1 | NCT00085930 | Active, No recruit |

| GD2 CAR multivirus specific | Relapsed or Refractory neuroblastoma (18 months to 17 years old) | 1 | NCT01460901 | Recruiting |

| GD2 CAR 3rd and iCaspase suicide | Relapsed or Refractory neuroblastoma | 1 | NCT01822652 | Recruiting |

| GD2 CAR 3rd VZV and iCaspase suicide | Refractory or metastatic GD2+ sarcoma | 1 | NCT01953900 | Recruiting |

| GD2 CAR 3rd | Non-neuroblastoma, GD2+ solid tumors (1-35 years old) | 1 | NCT02107963 | Recruiting |

| CD171 CAR 2nd | Refractory neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma (up to 18 yearsold) | 1 | NCT02311621 | Recruiting |

| CEA CAR | Adenocarcinoma | 1 | NCT00004178 | Completed |

| CEA CAR | CEA+ tumor | 1 | NCT01212887 | Terminated |

| CEA CAR 2nd 28 | Colorectal cancer | 1 | NCT00673322 | Terminated |

| CEA CAR 2nd 28 | CEA+ Adenocarcinoma with liver metastasis | 1 | NCT01373047 | Completed |

| CEA CAR 2nd 28 +/− IL-2 | Breast cancer | 1 | NCT00673829 | Active, No recruit |

| CEA CAR 2nd 28 + IL-2 | CEA+ Adenocarcinoma | 2 | NCT01723306 | Active, No recruit |

| EGFR CAR 2nd 137 | Relapsed or Refractory EGFR+ non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal | 1, 2 | NCT01869166 | Recruiting |

| EGFR CAR | Glioblastoma | 1 | NCT02331693 | Recruiting |

| EGFRvIII CAR | Glioblastoma | 1 | NCT02209376 | Recruiting |

| EGFRvIII CAR 3rd +/− IL-2 | Glioblastoma | 1, 2 | NCT01454596 | Recruiting |

| PSMA CAR 2nd | Castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer | 1 | NCT01140373 | Recruiting |

| Folate receptor CAR +/− IL-2 | Ovarian cancer | 1 | NCT00019136 | Completed |

| Mesothelin CAR 2nd | Ovarian cancer | 1 | NCT02159176 | Recruiting |

| IL-13 zetakine CAR | CNS tumors | 1 | NCT00730613 | Completed |

| IL13 receptor α2 CAR | Malignant glioma | 1 | NCT02208362 | Not yet recruiting |

| ErbB T4+ CAR 2nd 28 (intra tumoral) | Squamous cell cancer of the head and neck | 1 | NCT01818323 | Not yet recruiting |

| FAP CAR (intra pleural) | Malignant pleural mesothelioma | 1 | NCT01722149 | Recruiting |

1st, 1st generation; 2nd, 2nd generation; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CM T cells, central memory T cells; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CNS, central nervous system; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; EGFRt, truncated epidermal growth factor receptor; FAP, fibroblast activation protein; GD2, disialoganglioside; HER-2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplant; HyTK, hydromycin-thymidine kinase; IL-2, interleukin-2; IL-13, interleukin-13; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NKG2D, natural-killer group 2, member D; PSMA, prostate-specific membrane antigen; TCR, T cell receptor; TGFbeta DNR, transforming growth factor beta dominant negative receptor; VZV, varicella zoster virus

Table II.

Clinical trials of BsAbs (Pediatric studies highlighted) (as of Jan. 2015)

| BsAb; Target | Tumor type | Phase | Clinical trial | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catumaxomab (Removab); Trifunctional BsAb; EpCAM × CD3 |

Epithelial ovarian cancer | 2 | NCT00563836 | Completed |

| Epithelial ovarian cancer | 2 | NCT01815528 | Recruiting | |

| Epithelial ovarian cancer | 1 | NCT01320020 | Terminated | |

| Epithelial ovarian cancer, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer | 2 | NCT00189345 | Completed | |

| Epithelial ovarian cancer, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer | 2 | NCT00377429 | Completed | |

| Epithelial ovarian cancer, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer | 2 | NCT01246440 | Unknown | |

| Malignant ascites (epithelial ovarian cancer) | 2 | NCT01065246 | Completed | |

| Malignant ascites (epithelial ovarian cancer) | 3 | NCT00822809 | Completed | |

| Malignant ascites (epithelial ovarian cancer, fallopian tube cancer, or peritoneal cancer) |

2 | NCT00326885 | Completed | |

| Malignant ascites (EpCAM positive tumor; e.g. ovarian, gastric, colon, breast) | 2, 3 | NCT00836654 | Completed | |

| Gastric adenocarcinoma with macroscopic peritoneal carcinomatosis | 2 | NCT01784900 | Recruiting | |

| Gastric adenocarcinoma or adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction | 2 | NCT00352833 | Completed | |

| Gastric adenocarcinoma or adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction | 2 | NCT00464893 | Completed | |

| Gastric adenocarcinoma or adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction with macroscopic peritoneal carcinomatosis |

2 | NCT01504256 | Recruiting | |

| Ertumaxomab trifunctional BsAb; HER-2/neu × CD3 |

HER-2/neu expressing (1+ or 2+/FISH negative) hormone therapy refractory or metastatic breast cancer |

2 | NCT00452140 | Terminated |

| HER-2/neu expressing (1+ or 2+) hormone therapy refractory or metastatic breast cancer |

2 | NCT00351858 | Terminated | |

| HER-2/neu expressing (1+/FISH positive, 2+ or 3+) solid tumors | 1, 2 | NCT01569412 | Recruiting | |

| HER-2/neu overexpressing (2+/FISH positive or 3+) metastatic breast cancer | 2 | NCT00522457 | Terminated | |

| Blinatumomab (BiTE®); (MT103,AMG103); CD19 × CD3 FDA approved in 2014 (BlincytoTM) |

Relapsed or refractory B-precursor ALL | 2 | NCT01209286 | Active but not recruiting |

| Relapsed or refractory B-precursor ALL (up to 17 years old) | 1, 2 | NCT01471782 | Active but not recruiting | |

| Relapsed or refractory B-precursor ALL | 3 | NCT02013167 | Recruiting | |

| Relapsed B-precursor ALL (1 year old to 30 years old) | 3 | NCT02101853 | Recruiting | |

| Relapsed or refractory Philadelphia-chromosome(−) B-precursor ALL | 2 | NCT01466179 | Active but not recruiting | |

| Relapsed or refractory Philadelphia-chromosome(+) B-precursor ALL | 2 | NCT02000427 | Recruiting | |

| Minimal residual disease of B-precursor ALL | 2 | NCT01207388 | Active but not recruiting | |

| Minimal residual disease of B-precursor ALL | 2 | NCT00560794 | Completed | |

| Relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 2 | NCT01741792 | Active but not recruiting | |

| Relapsed non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 1 | NCT00274742 | Completed | |

| New diagnosis of B-precursor ALL | 3 | NCT02003222 | Recruiting | |

| New diagnosis of B-precursor ALL (≥ 65 years old) | 2 | NCT02143414 | Not yet recruiting | |

| FBTA05 trifunctional BsAb; CD20 × CD3 |

Relapsed or refractory CLL, low grade or high grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma with positive CD20 after allogeneic transplantation |

1, 2 | NCT01138579 | Recruiting |

| REGN1979 CD20 × CD3 |

Refractory CLL, non- Hodgkin lymphoma | 1 | NCT02290951 | Recruiting |

| Rituximab × OXT3; CD20 × CD3 |

Multiple myeloma, plasma neoplasm | 1 | NCT00938626 | Completed |

| MGD006; CD123 × CD3 |

Relapsed or refractory AML | 1 | NCT02152956 | Recruiting |

| MT110 (BiTE®); EpCAM × CD3 |

EpCAM positive tumor; e.g. ovarian, small cell lung, adenocarcinoma of the lung, gastric, colon, breast, prostate cancer |

1 | NCT00635596 | Completed |

| BAY2010112 (BiTE®); (MT112,AMG212); PSMA × CD3 |

Advanced castration-resistant prostate cancer | 1 | NCT01723475 | Recruiting |

| IMCgp100; gp100 × CD3 |

Stage III unresectable or IV malignant melanoma | 1 | NCT01211262 | Recruiting |

| rM28; HMV-MAA × CD28* |

Stage III or IV malignant melanoma with injectable soft tissue metastasis | 1, 2 | NCT00204594 | Completed |

| BAY2010112 (BiTE®); (MT112,AMG212); PSMA × CD3 |

Advanced castration-resistant prostate cancer | 1 | NCT01723475 | Recruiting |

| MOR209/ES414 PSMA × CD3 |

Progressive prostate cancer | 1 | NCT02262910 | Recruiting |

| MGD007: gpA33 × CD3 |

Metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma | 1 | NCT02248805 | Recruiting |

| RO6958688 CEA × CD3 |

Locally advanced/metastatic sold tumors | 1 | NCT00352833 | Recruiting |

CD28 is a cell surface costimulatory receptor on T cells; CD28 is required to activate T cell in addition to TCR-mediated signaling. ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; EpCAM, epitherial cell adhesion molecule; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; gp100, glycoprotein 100; HER-2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; hu3F8, humanized 3F8; PSMA, prostate-specific membrane antigen

Among BsAbs, catumaxomab for malignant ascites of the epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) positive cancers was approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2009. Blinatumomab, the BiTE® specific for CD19 positive leukemia or lymphoma, has shown clinical benefit [45-47, 68, 69] receiving FDA approval in 2014. Furthermore, the BiTE® (e.g. EpCAM, BsAb, MT110) and various BsAb platforms targeting solid tumors, including adenocarcinoma, breast cancer, and melanoma are actively being pursued. For the pediatric populations, targeting GD2 in solid tumors have shown promise in preclinical models [27, 35, 36, 43, 70]. Clinical trials of blinatumomab in lymphoblastic leukemia are ongoing and anti-GD2 BsAbs in solid tumors will soon be open (highlighted in Table II).

T cell redirection strategies for pediatric cancers

Pediatric cancer patients face unique challenges because of their young age, the metastatic tendency of their tumors, and long-term toxicity considerations in later years. In children, certain growth factor receptors and differentiation antigens, which are the potential targets of cancer therapy, are required for normal development (e.g. insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor) [71]. Currently, several CAR T cells and BsAbs are used in preclinical or clinical trials in children including CD19, CD30, and CD33 for hematologic malignancies, GD2 for osteosarcoma and embryonal cancers including neuroblastoma and rhabdomyosarcoma, and HER2 for sarcomas and brain tumors [64, 71] with relatively short follow-up (<5 years). Even though hypogammaglobulinemia from B-cell depletion by CD19-targeted therapy is treatable with gamma globulin infusions, pan B-cell deficit and its potential long term immune or autoimmune complications remains unknown. GD2-specific monoclonal antibodies have been used in treating pediatric neuroblastoma over the past 2 decades. Even though there were no observed late effects with anti-GD2 monoclonal antibodies or with anti-GD2 CAR T cells, careful long-term follow-up for potential damage of GD2(+) neurons is warranted.

Target discovery for redirecting T cells in pediatric cancers is continuing. ROR1 and ROR2 are examples of antigens too low in density for Fc-dependent tumor lysis. When incorporated into CAR T cell or BsAb technology, they hold anti-tumor potential. Glypican-3, glypican-5, GM2, and GD3 are other examples that deserve attention [71, 72].

Although pediatric embryonal cancers are more chemosensitive when compared to adult cancers [73], they tend to be widely metastatic to the bone, bone marrow, lymph nodes, lung, liver and the central nervous system (CNS). Here, the ability to deliver CAR T cells or BsAbs to these distinct metastatic sites can be critical, since inadequate treatment of one site will allow reseeding of cancer to the other organs. Many pediatric cancer regimens use intensive chemotherapy or radiation therapy resulting in the depletion of T cells and other immune cells. Without T cells, neither CAR T cells nor BsAb technology can be truly effective, and without other supporting immune cells, maximal tumor response cannot be achievable [27, 74]. Thus, it may be necessary to cryopreserve autologous T cells harvested before dose-intensive cytotoxic therapy. Alternatively, cytokines such as IL-7 and IL-15 may be necessary for lymphoid regeneration [75-77].

Future directions

As single modalities, CAR T cells and BsAbs have shown anti-tumor responses. By combining them with other targeted drugs with non-overlapping toxicities, their efficacy can be enhanced and the emergence of resistant cells can be prevented. For example, in neuroblastoma, CAR T cells or BsAbs directed at GD2 can be combined with other monoclonal antibodies to induce cell death (anti-DR4 or anti-DR5) [78], to remove immune checkpoint blockade (anti-CTLA4, anti-PD1, anti-PD-L1) [79], to disable growth factor pathways (anti-IGF1 and anti-IGF-2, anti-IGF-1R, anti-HGF-R, anti-EGF-R, anti-TrkB) [80, 81], to inhibit angiogenesis (anti-VEGF) [82], or to combine with cytokine that enhance CD8(+) T cells (e.g. IL-15) [77]. In the CD19-CAR T cell therapy of pre-B cell ALL, the escape of CD19(−) clones can pose substantial obstacles to cure. This can potentially be surmounted by using combination strategies such as the additional targeting through CD22 [83]. Small molecules targeting antigens involving tumor growth, invasion, metastasis, and resistance to cell death can also combine with T-cell redirection, as long as they do not interfere with T cell functions [84, 85].

CAR-modified leukemia-redirected autologous T cells may provide an alternative to allogeneic stem cell transplantation. In allogeneic transplantation, cytoreduction with intensive chemotherapy and/or radiation is required prior to stem cell infusion to prevent graft failure, followed by immunosuppression to prevent graft versus host disease (GVHD). The accompanying toxicities from GVHD and opportunistic infections have compromised quality of life and survival. It is conceivable that CAR-modified autologous T cells alone or in combination with autologous stem cell transplant, which have less acute and long-term toxicity compared to allogeneic transplant, could achieve similar anti-tumor benefits. Furthermore, autologous stem cell harvests can also be purged ex vivo using CAR-modified autologous T cells or BsAb to reduce tumor cell contamination before cryopreservation or before reinfusion.

Conclusion

CAR T cells and BsAbs are novel T-cell based therapies; each has its unique advantages and challenges. Both have shown impressive clinical efficacy in leukemia and lymphoma. As these platforms are fine-tuned, their relevance for solid tumors should become more obvious. CAR T cells require sophisticated cytotherapy, and intense supportive care pre- and post-injection. Similar to other monoclonal antibodies, BsAbs are likely to be more acceptable in a non-specialized clinic setting for the treatment of the more prevalent cancers, be it liquid or solid tumors, especially for patients who require immediate therapy, or those with suboptimal clinical conditions likely to be imperiled by additional high dose chemotherapy. In children, late effects are critical considerations. As T-cell based therapies for pediatric cancer enter the ongoing accelerated phase of development, exciting possibilities will likely become available in not too distant future.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Irene Y. Cheung and Joseph Olechnowicz for reviewing and editing the manuscript, as well as Dr. Hollie Pegram for her assistance in generating the figure in this manuscript. This work was partially supported by Enid A Haupt Endowed Chair, and grants from Kids Walk for Kids with Cancer NYC, Katie’s Find a Cure Foundation, Catie Hoch Foundation and the Robert Steel Foundation.

Footnotes

Potential Conflict of Interest Statement

NK. V. Cheung has ownership interest (including patents) in scfv constructs of anti-GD2 antibodies, therapy-enhancing glucan, use of mAb 8H9, methods for preparing and using scFv, GD2 peptide mimics, methods for detecting MRD, anti-GD2 antibodies, generation and use of HLA-A2–restricted peptide-specific mAbs and CARs, high-affinity anti-GD2 antibodies, and multimerization technologies. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

References

- 1.Coley WB. The Treatment of Inoperable Sarcoma by Bacterial Toxins (the Mixed Toxins of the Streptococcus erysipelas and the Bacillus prodigiosus) Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1910;3:1–48. doi: 10.1177/003591571000301601. Surg Sect. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burnet M. Cancer; a biological approach. I. The processes of control. British medical journal. 1957;1(5022):779–786. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5022.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawrence HS. Cellular and humoral aspects of the hypersensitive states; a symposium held at the New York Academy of Medicine. xii. P.B. Hoeber; New York: 1959. p. 667. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas ED, Lochte HL, Jr., Cannon JH, Sahler OD, Ferrebee JW. Supralethal whole body irradiation and isologous marrow transplantation in man. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1959;38:1709–1716. doi: 10.1172/JCI103949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity's roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331(6024):1565–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.1203486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishikawa H, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Current opinion in immunology. 2014;27:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diaz-Montero CM, Finke J, Montero AJ. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer: therapeutic, predictive, and prognostic implications. Seminars in oncology. 2014;41(2):174–184. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laoui D, Van Overmeire E, De Baetselier P, Van Ginderachter JA, Raes G. Functional Relationship between Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor as Contributors to Cancer Progression. Frontiers in immunology. 2014;5:489. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyi C, Postow MA. Checkpoint blocking antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. FEBS letters. 2014;588(2):368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yano H, Thakur A, Tomaszewski EN, Choi M, Deol A, Lum LG. Ipilimumab augments antitumor activity of bispecific antibody-armed T cells. Journal of translational medicine. 2014;12:191. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kershaw MH, Westwood JA, Parker LL, Wang G, Eshhar Z, Mavroukakis SA, White DE, Wunderlich JR, Canevari S, Rogers-Freezer L, Chen CC, Yang JC, Rosenberg SA, Hwu P. A phase I study on adoptive immunotherapy using gene-modified T cells for ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20 Pt 1):6106–6115. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pule MA, Savoldo B, Myers GD, Rossig C, Russell HV, Dotti G, Huls MH, Liu E, Gee AP, Mei Z, Yvon E, Weiss HL, Liu H, Rooney CM, Heslop HE, Brenner MK. Virus-specific T cells engineered to coexpress tumor-specific receptors: persistence and antitumor activity in individuals with neuroblastoma. Nature medicine. 2008;14(11):1264–1270. doi: 10.1038/nm.1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louis CU, Savoldo B, Dotti G, Pule M, Yvon E, Myers GD, Rossig C, Russell HV, Diouf O, Liu E, Liu H, Wu MF, Gee AP, Mei Z, Rooney CM, Heslop HE, Brenner MK. Antitumor activity and long-term fate of chimeric antigen receptor-positive T cells in patients with neuroblastoma. Blood. 2011;118(23):6050–6056. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-354449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kowolik CM, Topp MS, Gonzalez S, Pfeiffer T, Olivares S, Gonzalez N, Smith DD, Forman SJ, Jensen MC, Cooper LJ. CD28 costimulation provided through a CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor enhances in vivo persistence and antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred T cells. Cancer research. 2006;66(22):10995–11004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finney HM, Lawson ADG, Bebbington CR, Weir NC. Chimeric receptors providing both primary and costimulatory signaling in T cells from a single gene product. J Immunol. 1998;161:2791–2797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hombach A, Wieczarkowiecz A, Marquardt T, Heuser C, Usai L, Pohl C, Seliger B, Abken H. Tumor-specific T cell activation by recombinant immunoreceptors: CD3 zeta signaling and CD28 costimulation are simultaneously required for efficient IL-2 secretion and can be integrated into one combined CD28/CD3 zeta signaling receptor molecule. J Immunol. 2001;167(11):6123–6131. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tammana S, Huang X, Wong M, Milone MC, Ma L, Levine BL, June CH, Wagner JE, Blazar BR, Zhou X. 4-1BB and CD28 signaling plays a synergistic role in redirecting umbilical cord blood T cells against B-cell malignancies. Human gene therapy. 2010;21(1):75–86. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song DG, Ye Q, Poussin M, Harms GM, Figini M, Powell DJ., Jr. CD27 costimulation augments the survival and antitumor activity of redirected human T cells in vivo. Blood. 2012;119(3):696–706. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-344275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Till BG, Jensen MC, Wang J, Qian X, Gopal AK, Maloney DG, Lindgren CG, Lin Y, Pagel JM, Budde LE, Raubitschek A, Forman SJ, Greenberg PD, Riddell SR, Press OW. CD20-specific adoptive immunotherapy for lymphoma using a chimeric antigen receptor with both CD28 and 4-1BB domains: pilot clinical trial results. Blood. 2012;119(17):3940–3950. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-387969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pegram HJ, Lee JC, Hayman EG, Imperato GH, Tedder TF, Sadelain M, Brentjens RJ. Tumor-targeted T cells modified to secrete IL-12 eradicate systemic tumors without need for prior conditioning. Blood. 2012;119(18):4133–4141. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-400044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staerz UD, Kanagawa O, Bevan MJ. Hybrid antibodies can target sites for attack by T cells. Nature. 1985;314:628–631. doi: 10.1038/314628a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milstein C, Cuello AC. Hybrid hybridomas and their use in immunohistochemistry. Nature. 1983;305(5934):537–540. doi: 10.1038/305537a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satta A, Mezzanzanica D, Turatti F, Canevari S, Figini M. Redirection of T-cell effector functions for cancer therapy: bispecific antibodies and chimeric antigen receptors. Future Oncol. 2013;9(4):527–539. doi: 10.2217/fon.12.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kontermann R. Dual targeting strategies with bispecific antibodies. mAbs. 2012;4(2) doi: 10.4161/mabs.4.2.19000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mack M, Riethmuller G, Kufer P. A small bispecific antibody construct expressed as a functional single-chain molecule with high tumor cell cytotoxicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92(15):7021–7025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.7021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baeuerle PA, Reinhardt C. Bispecific T-cell engaging antibodies for cancer therapy. Cancer research. 2009;69(12):4941–4944. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu H, Cheng M, Guo H, Chen Y, Huse M, Cheung NK. Retargeting T cells to GD2 pentasaccharide on human tumors using bispecific humanized antibody. Cancer immunology research. 2014 doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0230-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi BD, Gedeon PC, Sanchez-Perez L, Bigner DD, Sampson JH. Regulatory T cells are redirected to kill glioblastoma by an EGFRvIII-targeted bispecific antibody. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(12):e26757. doi: 10.4161/onci.26757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kofler DM, Chmielewski M, Rappl G, Hombach A, Riet T, Schmidt A, Hombach AA, Wendtner CM, Abken H. CD28 costimulation Impairs the efficacy of a redirected t-cell antitumor attack in the presence of regulatory t cells which can be overcome by preventing Lck activation. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2011;19(4):760–767. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee JC, Hayman E, Pegram HJ, Santos E, Heller G, Sadelain M, Brentjens R. In vivo inhibition of human CD19-targeted effector T cells by natural T regulatory cells in a xenotransplant murine model of B cell malignancy. Cancer research. 2011;71(8):2871–2881. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stone JD, Aggen DH, Schietinger A, Schreiber H, Kranz DM. A sensitivity scale for targeting T cells with chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) and bispecific T-cell Engagers (BiTEs) Oncoimmunology. 2012;1(6):863–873. doi: 10.4161/onci.20592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chmielewski M, Hombach A, Heuser C, Adams GP, Abken H. T cell activation by antibody-like immunoreceptors: increase in affinity of the single-chain fragment domain above threshold does not increase T cell activation against antigen-positive target cells but decreases selectivity. J Immunol. 2004;173(12):7647–7653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curran KJ, Pegram HJ, Brentjens RJ. Chimeric antigen receptors for T cell immunotherapy: current understanding and future directions. The journal of gene medicine. 2012;14(6):405–415. doi: 10.1002/jgm.2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haso W, Lee DW, Shah NN, Stetler-Stevenson M, Yuan CM, Pastan IH, Dimitrov DS, Morgan RA, FitzGerald DJ, Barrett DM, Wayne AS, Mackall CL, Orentas RJ. Anti-CD22-chimeric antigen receptors targeting B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2013;121(7):1165–1174. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-438002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng M, Ahmed M, Xu H, Cheung NK. Structural design of disialoganglioside GD2 and CD3-bispecific antibodies to redirect T cells for tumor therapy. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ijc.29007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed M, Cheng M, Cheung IY, Cheung NK. Human derived dimerization tag enhances tumor killing potency of a T-cell engaging bispecific antibody. Oncoimmunology. 2015 doi: 10.4161/2162402X.2014.989776. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgan RA, Yang JC, Kitano M, Dudley ME, Laurencot CM, Rosenberg SA. Case report of a serious adverse event following the administration of T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor recognizing ERBB2. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2010;18(4):843–851. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beckman RA, Weiner LM, Davis HM. Antibody constructs in cancer therapy: protein engineering strategies to improve exposure in solid tumors. Cancer. 2007;109(2):170–179. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kershaw MH, Wang G, Westwood JA, Pachynski RK, Tiffany HL, Marincola FM, Wang E, Young HA, Murphy PM, Hwu P. Redirecting migration of T cells to chemokine secreted from tumors by genetic modification with CXCR2. Human gene therapy. 2002;13(16):1971–1980. doi: 10.1089/10430340260355374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Stasi A, De Angelis B, Rooney CM, Zhang L, Mahendravada A, Foster AE, Heslop HE, Brenner MK, Dotti G, Savoldo B. T lymphocytes coexpressing CCR4 and a chimeric antigen receptor targeting CD30 have improved homing and antitumor activity in a Hodgkin tumor model. Blood. 2009;113(25):6392–6402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang H, Bi XG, Yuan JY, Xu SL, Guo XL, Xiang J. Combined CD4+ Th1 effect and lymphotactin transgene expression enhance CD8+ Tc1 tumor localization and therapy. Gene therapy. 2005;12(12):999–1010. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russell HV, Strother D, Mei Z, Rill D, Popek E, Biagi E, Yvon E, Brenner M, Rousseau R. A Phase 1/2 Study of Autologous Neuroblastoma Tumor Cells Genetically Modified to Secrete IL-2 in Patients With High-risk Neuroblastoma. J Immunother. 2008 doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181869893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheal SM, Xu H, Guo HF, Zanzonico PB, Larson SM, Cheung NK. Preclinical Evaluation of Multistep Targeting of Diasialoganglioside GD2 Using an IgG-scFv Bispecific Antibody with High Affinity for GD2 and DOTA Metal Complex. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2014;13(7):1803–1812. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Junttila TT, Li J, Johnston J, Hristopoulos M, Clark R, Ellerman D, Wang BE, Li Y, Mathieu M, Li G, Young J, Luis E, Lewis Phillips G, Stefanich E, Spiess C, Polson A, Irving B, Scheer JM, Junttila MR, Dennis MS, Kelley R, Totpal K, Ebens A. Antitumor Efficacy of a Bispecific Antibody That Targets HER2 and Activates T Cells. Cancer research. 2014;74(19):5561–5571. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3622-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heiss MM, Strohlein MA, Jager M, Kimmig R, Burges A, Schoberth A, Jauch KW, Schildberg FW, Lindhofer H. Immunotherapy of malignant ascites with trifunctional antibodies. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2005;117(3):435–443. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burges A, Wimberger P, Kumper C, Gorbounova V, Sommer H, Schmalfeldt B, Pfisterer J, Lichinitser M, Makhson A, Moiseyenko V, Lahr A, Schulze E, Jager M, Strohlein MA, Heiss MM, Gottwald T, Lindhofer H, Kimmig R. Effective relief of malignant ascites in patients with advanced ovarian cancer by a trifunctional anti-EpCAM × anti-CD3 antibody: a phase I/II study. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(13):3899–3905. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jager M, Schoberth A, Ruf P, Hess J, Hennig M, Schmalfeldt B, Wimberger P, Strohlein M, Theissen B, Heiss MM, Lindhofer H. Immunomonitoring results of a phase II/III study of malignant ascites patients treated with the trifunctional antibody catumaxomab (anti-EpCAM × anti-CD3) Cancer research. 2012;72(1):24–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chames P, Baty D. Bispecific antibodies for cancer therapy: the light at the end of the tunnel? mAbs. 2009;1(6):539–547. doi: 10.4161/mabs.1.6.10015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robbins PF, Dudley ME, Wunderlich J, El-Gamil M, Li YF, Zhou J, Huang J, Powell DJ, Jr., Rosenberg SA. Cutting edge: persistence of transferred lymphocyte clonotypes correlates with cancer regression in patients receiving cell transfer therapy. J Immunol. 2004;173(12):7125–7130. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, Aplenc R, Barrett DM, Bunin NJ, Chew A, Gonzalez VE, Zheng Z, Lacey SF, Mahnke YD, Melenhorst JJ, Rheingold SR, Shen A, Teachey DT, Levine BL, June CH, Porter DL, Grupp SA. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;371(16):1507–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davila ML, Riviere I, Wang X, Bartido S, Park J, Curran K, Chung SS, Stefanski J, Borquez-Ojeda O, Olszewska M, Qu J, Wasielewska T, He Q, Fink M, Shinglot H, Youssif M, Satter M, Wang Y, Hosey J, Quintanilla H, Halton E, Bernal Y, Bouhassira DC, Arcila ME, Gonen M, Roboz GJ, Maslak P, Douer D, Frattini MG, Giralt S, Sadelain M, Brentjens R. Efficacy and toxicity management of 19-28z CAR T cell therapy in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science translational medicine. 2014;6(224):224ra225. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee DW, Kochenderfer JN, Stetler-Stevenson M, Cui YK, Delbrook C, Feldman SA, Fry TJ, Orentas R, Sabatino M, Shah NN, Steinberg SM, Stroncek D, Tschernia N, Yuan C, Zhang H, Zhang L, Rosenberg SA, Wayne AS, Mackall CL. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61403-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muranski P, Boni A, Wrzesinski C, Citrin DE, Rosenberg SA, Childs R, Restifo NP. Increased intensity lymphodepletion and adoptive immunotherapy--how far can we go? Nature clinical practice Oncology. 2006;3(12):668–681. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wrzesinski C, Paulos CM, Kaiser A, Muranski P, Palmer DC, Gattinoni L, Yu Z, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Increased intensity lymphodepletion enhances tumor treatment efficacy of adoptively transferred tumor-specific T cells. J Immunother. 2010;33(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181b88ffc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berger C, Jensen MC, Lansdorp PM, Gough M, Elliott C, Riddell SR. Adoptive transfer of effector CD8+ T cells derived from central memory cells establishes persistent T cell memory in primates. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118(1):294–305. doi: 10.1172/JCI32103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hinrichs CS, Borman ZA, Cassard L, Gattinoni L, Spolski R, Yu Z, Sanchez-Perez L, Muranski P, Kern SJ, Logun C, Palmer DC, Ji Y, Reger RN, Leonard WJ, Danner RL, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Adoptively transferred effector cells derived from naive rather than central memory CD8+ T cells mediate superior antitumor immunity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(41):17469–17474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907448106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crellin NK, Garcia RV, Levings MK. Altered activation of AKT is required for the suppressive function of human CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Blood. 2007;109(5):2014–2022. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-035279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annual review of immunology. 2012;30:531–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun J, Dotti G, Huye LE, Foster AE, Savoldo B, Gramatges MM, Spencer DM, Rooney CM. T cells expressing constitutively active Akt resist multiple tumor-associated inhibitory mechanisms. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2010;18(11):2006–2017. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Portell CA, Wenzell CM, Advani AS. Clinical and pharmacologic aspects of blinatumomab in the treatment of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clinical pharmacology : advances and applications. 2013;5(Suppl 1):5–11. doi: 10.2147/CPAA.S42689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fiedler WM, Wolf M, Kebenko M, Goebeler ME, Ritter B, Quaas A, Vieser E, Hijazi Y, Patzak I, Friedrich M, Kufer P, Frankel S, Seggewiss-Bernhardt R, Kaubitzsch S. A phase I study of EpCAM/CD3-bispecific antibody (MT110) in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl) abstr 2504. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Friedrich M, Raum T, Lutterbuese R, Voelkel M, Deegen P, Rau D, Kischel R, Hoffmann P, Brandl C, Schuhmacher J, Mueller P, Finnern R, Fuergut M, Zopf D, Slootstra JW, Baeuerle PA, Rattel B, Kufer P. Regression of human prostate cancer xenografts in mice by AMG 212/BAY2010112, a novel PSMA/CD3-Bispecific BiTE antibody cross-reactive with non-human primate antigens. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2012;11(12):2664–2673. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ahmed N, Brawley V, Diouf O, Anderson P, Hicks J, Wang L, Dotti G, Wels W, Liu H, Gee A, Rooney C, Brenner M, Heslop H, Gottschalk S. Abstract 3500: T cells redirected against HER2 for the adoptive immunotherapy for HER2-positive osteosarcoma. Cancer research. 2012:72. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee DW, Barrett DM, Mackall C, Orentas R, Grupp SA. The future is now: chimeric antigen receptors as new targeted therapies for childhood cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(10):2780–2790. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Plumridge H. New Costly Cancer Treatments Face Hurdles Getting to Patients. The Wall Street Journal. 2014 Oct 6; [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pierson R. Exclusive: Amgen's new leukemia drug to carry $178,000 price tag. REUTERS. 2014 Dec 17; [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee DW, Gardner R, Porter DL, Louis CU, Ahmed N, Jensen M, Grupp SA, Mackall CL. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of cytokine release syndrome. Blood. 2014;124(2):188–195. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-552729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Klinger M, Brandl C, Zugmaier G, Hijazi Y, Bargou RC, Topp MS, Gokbuget N, Neumann S, Goebeler M, Viardot A, Stelljes M, Bruggemann M, Hoelzer D, Degenhard E, Nagorsen D, Baeuerle PA, Wolf A, Kufer P. Immunopharmacologic response of patients with B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia to continuous infusion of T cell-engaging CD19/CD3-bispecific BiTE antibody blinatumomab. Blood. 2012;119(26):6226–6233. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-400515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Topp MS, Kufer P, Gokbuget N, Goebeler M, Klinger M, Neumann S, Horst HA, Raff T, Viardot A, Schmid M, Stelljes M, Schaich M, Degenhard E, Kohne-Volland R, Bruggemann M, Ottmann O, Pfeifer H, Burmeister T, Nagorsen D, Schmidt M, Lutterbuese R, Reinhardt C, Baeuerle PA, Kneba M, Einsele H, Riethmuller G, Hoelzer D, Zugmaier G, Bargou RC. Targeted therapy with the T-cell-engaging antibody blinatumomab of chemotherapy-refractory minimal residual disease in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients results in high response rate and prolonged leukemia-free survival. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(18):2493–2498. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yankelevich M, Kondadasula SV, Thakur A, Buck S, Cheung NK, Lum LG. Anti-CD3 × anti-GD2 bispecific antibody redirects T-cell cytolytic activity to neuroblastoma targets. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1002/pbc.24237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Orentas RJ, Lee DW, Mackall C. Immunotherapy targets in pediatric cancer. Frontiers in oncology. 2012;2:3. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Williamson D, Selfe J, Gordon T, Lu YJ, Pritchard-Jones K, Murai K, Jones P, Workman P, Shipley J. Role for amplification and expression of glypican-5 in rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer research. 2007;67(1):57–65. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scott AM, Wolchok JD, Old LJ. Antibody therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):278–287. doi: 10.1038/nrc3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Textor A, Listopad J, Wuhrmann LL, Perez C, Kruschinski A, Chmielewski M, Abken H, Blankenstein T, Charo J. Efficacy of CAR T cell therapy in large tumors relies upon stromal targeting by IFNgamma. Cancer research. 2014 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dudakov JA, van den Brink MR. Greater than the sum of their parts: combination strategies for immune regeneration following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Best practice & research Clinical haematology. 2011;24(3):467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Alpdogan O, Eng JM, Muriglan SJ, Willis LM, Hubbard VM, Tjoe KH, Terwey TH, Kochman A, van den Brink MR. Interleukin-15 enhances immune reconstitution after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2005;105(2):865–873. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Steel JC, Waldmann TA, Morris JC. Interleukin-15 biology and its therapeutic implications in cancer. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2012;33(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Forero-Torres A, Shah J, Wood T, Posey J, Carlisle R, Copigneaux C, Luo FR, Wojtowicz-Praga S, Percent I, Saleh M. Phase I trial of weekly tigatuzumab, an agonistic humanized monoclonal antibody targeting death receptor 5 (DR5) Cancer biotherapy & radiopharmaceuticals. 2010;25(1):13–19. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2009.0673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zamarin D, Postow MA. Immune checkpoint modulation: Rational design of combination strategies. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hecht M, Schulte JH, Eggert A, Wilting J, Schweigerer L. The neurotrophin receptor TrkB cooperates with c-Met in enhancing neuroblastoma invasiveness. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26(12):2105–2115. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weigel B, Malempati S, Reid JM, Voss SD, Cho SY, Chen HX, Krailo M, Villaluna D, Adamson PC, Blaney SM. Phase 2 trial of cixutumumab in children, adolescents, and young adults with refractory solid tumors: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2014;61(3):452–456. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Patterson DM, Gao D, Trahan DN, Johnson BA, Ludwig A, Barbieri E, Chen Z, Diaz-Miron J, Vassilev L, Shohet JM, Kim ES. Effect of MDM2 and vascular endothelial growth factor inhibition on tumor angiogenesis and metastasis in neuroblastoma. Angiogenesis. 2011;14(3):255–266. doi: 10.1007/s10456-011-9210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Grupp SA, Kalos M, Barrett D, Aplenc R, Porter DL, Rheingold SR, Teachey DT, Chew A, Hauck B, Wright JF, Milone MC, Levine BL, June CH. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368(16):1509–1518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cheung NK, Dyer MA. Neuroblastoma: Developmental Biology, Cancer Genomics, and Immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2013;13:397–411. doi: 10.1038/nrc3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]