Abstract

BACKGROUND

The recent overdiagnosis of subclinical, low-risk papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) coincides with a growing national interest in cost-effective health care practices. The aim of this study was to measure the relative cost-effectiveness of disease surveillance of low-risk PTC patients versus intermediate- and high-risk patients in accordance with American Thyroid Association risk categories.

METHODS

Two thousand nine hundred thirty-two patients who underwent thyroidectomy for differentiated thyroid cancer between 2000 and 2010 were identified from the institutional database; 1845 patients were excluded because they had non-PTC cancer, underwent less than total thyroidectomy, had a secondary cancer, or had <36 months of follow-up. In total, 1087 were included for analysis. The numbers of postoperative blood tests, imaging scans and biopsies, clinician office visits, and recurrence events were recorded for the first 36 months of follow-up. Costs of surveillance were determined with the Physician Fee Schedule and Clinical Lab Fee Schedule of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

RESULTS

The median age was 44 years (range, 7–83 years). In the first 36 months after thyroidectomy, there were 3, 44, and 22 recurrences (0.8%, 7.8%, and 13.4%) in the low-, intermediate-, and high-risk categories, respectively. The cost of surveillance for each recurrence detected was US $147,819, US $22,434, and US $20,680, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

The cost to detect a recurrence in a low-risk patient is more than 6 and 7 times greater than the cost for intermediate- and high-risk PTC patients. It is difficult to justify this allocation of resources to the surveillance of low-risk patients. Surveillance strategies for the low-risk group should, therefore, be restructured.

Keywords: cost-effectiveness analysis, epidemiology, recurrence, thyroid neoplasm, ultrasonography

INTRODUCTION

The increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States and many parts of the world has been well documented in recent years.1–3 In the United States, the incidence of thyroid cancer has nearly tripled in the last 30 years from 4.9 to 14.3 per 100,000 individuals. This is largely due to an increase in the diagnosis of subclinical disease arising largely from increased sensitivity and frequency of ultrasound use.4 Despite this increase in thyroid cancer incidence, mortality rates have been remarkably stable at 0.5 deaths per 100,000.1 The combined effect of this increased diagnosis of low-risk disease, increased sensitivity of tools for disease surveillance, and stable disease mortality is a dramatic increase in the pool of papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) survivors in need of disease surveillance. Limited attention has been directed toward the clinical and financial implications for surveillance these thyroid cancer survivors.5 Which is especially important at a time of growing national interest in cost-effective health care. It is against this backdrop that we sought to analyze our institution’s surveillance practice for PTC patients. Our aim was to measure the relative cost-effectiveness of disease surveillance on the basis of American Thyroid Association (ATA) risk categories.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Following approval by the Institutional Review Board, records of Two thousand nine hundred thirty-two patients who underwent thyroidectomy for differentiated thyroid cancer between January 2000 and December 2010 at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center were reviewed. Only surveillance within 36 months of primary total thyroidectomy was included for analysis. The choice for the 3-year time frame was 2-fold. First, the literature suggests that the majority of recurrences in PTC occur within the first 2 to 3 years after the diagnosis.6 Second, the costs associated with surveillance for thyroid cancer are mostly incurred immediately after surgery. Unless the recurrence event developed within 3 years of surgery, all patients completed 3 years of follow-up. One thousand eight hundred forty-five patients were excluded from the analysis for one or more of the following indications. One hundred two patients (5.5%) were excluded for having nonpapillary histology, 487 patients (26.2%) were excluded for having a secondary cancer diagnosis, 65 patients (3.5%) were excluded because of surgical management outside of the head and neck department, 483 (26.4%) were excluded for less than total thyroidectomy, and 704 patients (38.2%) without a recurrence event and less than 36 months of follow-up were excluded. This left 1087 patients available for analysis. The inclusion cohort was stratified into low, intermediate, and high recurrence risk categories as per the ATA classification system7 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

American Thyroid Association Risk Categories, 2009 Edition

| Low Risk | Intermediate Risk | High Risk |

|---|---|---|

| No local or distant metastases | Microscopic perithyroidal invasion | Macroscopic tumor invasion |

| All macroscopic disease resected | Cervical lymph node metastases or 131 I uptake outside thyroid bed on posttreatment scan, if done |

Gross residual disease |

| No locoregional invasion | Aggressive histology | Distant metastases |

| No aggressive histology | ||

| No vascular invasion | ||

| No 131I uptake outside thyroid bed on posttreatment scan, if done |

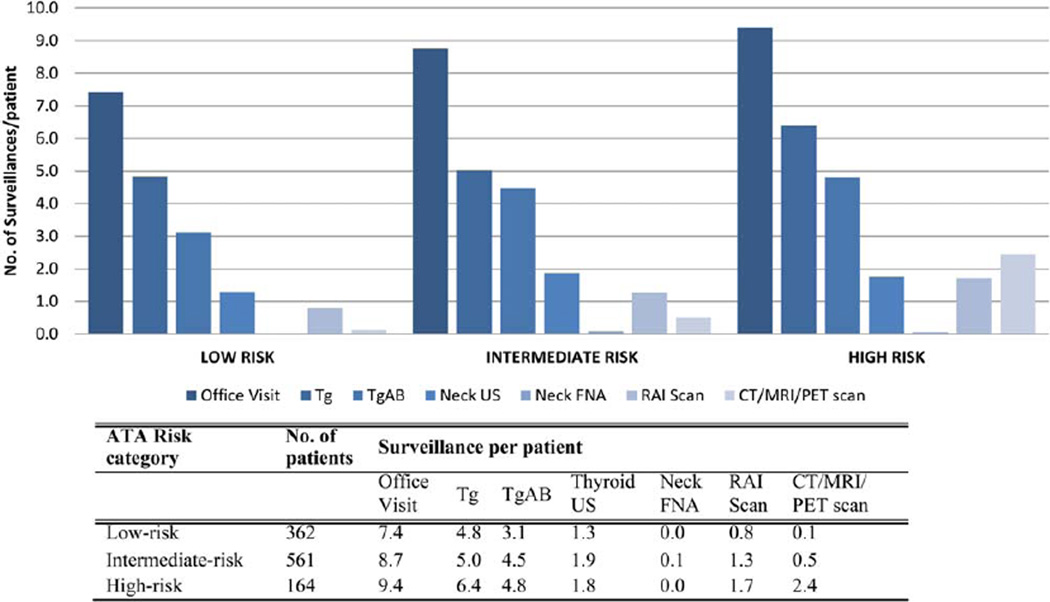

The number of postoperative serum thyroglobulin (Tg) tests, Tg antibody tests, imaging studies (including ultrasound, computer tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, and fine-needle aspiration biopsy), and office visits for thyroid cancer were recorded in the first 36 months of follow-up by retrospective chart review (Fig. 1). Disease recurrence events were similarly recorded.

Figure 1.

Inclusion cohort. ATA indicates American Thyroid Association; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; Mx, management.

Costs of surveillance were determined with the fee schedules of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). For services involving a physician (ie, radiologic or nonlaboratory tests/procedures), the 2014 Medicare National Payment Amount nonfacility reimbursement rates were obtained from the CMS Physician Fee Schedule Search Web site through the entry of the appropriate Current Procedural Terminology/Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code.8 Current Procedural Terminology codes are a trademark of the American Medical Association; they correspond to Medicare’s Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System level I codes. The dollar amount includes the “26” professional component and the technical component. For laboratory services, the 2014 CMS Clinical Lab Fee Schedule was used to determine midpoint reimbursement fees.9

The total cost of surveillance for each ATA risk category was calculated by the summation of the cost of each surveillance investigation for each patient within the risk category. The cost of surveillance for an average patient was calculated by the division of the total cost by the number of patients under surveillance in each risk group. The benefit of disease surveillance was measured by the detection of recurrence events in each ATA risk category. The cost to detect 1 recurrence event was calculated by the division of the cost of surveillance for all patients by the number of recurrence events in each respective risk category.

The calculated ratios of cost per recurrence were dependent in this analysis on actual clinical data of events gathered from this cohort. Therefore, a deterministic sensitivity analysis was performed to analyze the robustness of these results. In the first sensitivity analysis, we varied the rate of recurrences by a factor of 3 in all risk groups and determined the cost per recurrence. We chose a factor of 3 because this approximates higher published rates of recurrence based on 2009 ATA risk stratification.10,11 For the second sensitivity analysis, we varied the rate of testing. Specifically, we varied the rate of ultrasonography by a factor of 3 in all risk groups and determined the cost per recurrence. We only to vary chose ultrasound rates because our observed rates of 1 to 2 ultrasounds per patient in a 3-year period might realistically be as high as 6 at some institutions (every 6 months as suggested as a maximum in the 2009 ATA guidelines). We did not vary the number of other tests because 1) it seems unlikely that patients would get several factors more or less of Tg or radioactive iodine scans than our observed group, for example and 2) there are no guidelines or published higher or lower rates of these other tests and procedures.

RESULTS

The median age was 44 years (range, 7–83 years). Three-hundred sixty-two patients (33.3%) were low-risk, 561 (51.6%) were intermediate-risk, and 164 (15.1%) were high-risk according to the ATA. The rates of recurrence in the low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups were 0.8% (n = 3), 7.8% (n = 44), and 13.4% (n = 22), respectively.

Surveillance Cost per Patient

Table 2 presents the Medicare cost associations with thyroid cancer surveillance as per the CMS reimbursement schedules.8,9 The number of surveillance office visits with Memorial Sloan Kettering clinicians and the number of serum Tg, Tg antibody, and imaging scans performed in the first 36 months of surveillance at our institution are shown in Table 3 and Figure 2. The overall Medicare reimbursement cost of surveillance was US $443,456 for low-risk patients, US $987,080 for intermediate-risk patients, and US $454,961 for all high-risk patients (ATA categories). For patients in the low-, intermediate-, and high-risk categories, the Medicare reimbursement cost of surveillance was US $1225, US $1760, and US $2774 respectively. The relative cost of surveillance for an individual patient with an intermediate risk of recurrence was 1.4 times the cost of surveillance for a low-risk patient. For a patient with a high risk of recurrence, the surveillance cost was 2.3 times greater than that for a low-risk patient.

TABLE 2.

Cost per Surveillance Modality

| Cost (US $) |

CPT/ HCPCS Code |

Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Office visit | 73.08 | 99213 | CMS Physician Fee Schedule |

| Tg test | 29.61 | 84432 | CMS Clinical Lab Fee Schedule |

| Tg Ab test | 29.32 | 86800 | CMS Clinical Lab Fee Schedule |

| Neck ultrasound | 123.59 | 76536 | CMS Physician Fee Schedule |

| FNA of neck | 295.89 | –a | CMS Physician Fee Schedule |

| RAI scan | 319.54 | 78018 | CMS Physician Fee Schedule |

| CT scan | 247.89 | 70491 | CMS Physician Fee Schedule |

| MRI scan | 510.47 | 70543 | CMS Physician Fee Schedule |

| PET scan | 693.51 | –b | CMS Physician Fee Schedule |

Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; CMS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; CT, computed tomography; FNA, fine-needle aspirate; HCPCS, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography; RAI, radioactive iodine; Tg, thyroglobulin

Multiple codes are billed when this study is performed: initial for adequacy ($146.87, code 88173); first determination ($54.45, code 88172); and special stains, first group ($94.57, code 88312).

Multiple codes are billed when this study is performed: PET component ($124.31, code 78815), CT chest ($241.80, code 71260); and CT abdomen/pelvis ($327.40, code 74177)

TABLE 3.

First 3 Years of Surveillance for Patients With Papillary Thyroid Cancer Undergoing Operations Between 2000 and 2010

| Surveillance Investigations in 36 mo, (per risk category) |

Surveillance Cost (US $) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATA Risk Category |

Patients. No. (%) |

Recurrences. No. (%) |

Office Visit | Tg | Tg Ab | Neck US |

Neck FNA |

RAI Scan |

CT/MRI/ PET Scan |

Overall Cost |

Cost per Patient |

Cost per Recurrence |

| Low | 362 (33.3) | 3 (0.8) | 2686 (7.4) | 1748(4.8) | 1127(3.1) | 462 (1.3) | 7 (0.02) | 288 (0.80) | 39(0.11) | 443,456 | 1225 | 147,819 |

| Intermediate | 561 (51.6) | 44 (7.8) | 4907 (8.7) | 2817(5.0) | 2509 (4.5) | 1050(1.9) | 43 (0.08) | 706 (1.26) | 275 (0.49) | 987,080 | 1760 | 22,434 |

| High | 164(15.1) | 22 (13.4) | 1542 (9.4) | 1047(6.4) | 789 (4.8) | 287 (1.8) | 8 (0.05) | 281 (1.71) | 401 (2.45) | 454,961 | 2774 | 20,680 |

| Total | 1087 | 69 | 9135 | 5612 | 4425 | 1799 | 58 | 1275 | 715 | 1,885,497 | 1735 | 27,326 |

Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; ATA, American Thyroid Association; CT, computed tomography; FNA, fine-needle aspirate; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography; RAI, radioactive iodine; Tg, thyroglobulin; US, ultrasound.

Figure 2.

Surveillance by ATA risk category in the first 3 years after thyroidectomy. Ab indicates antibody; ATA, American Thyroid Association; CT, computed tomography; FNA, fine-needle aspirate; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography; RAI, radioactive iodine; Tg, thyroglobulin; US, ultrasound.

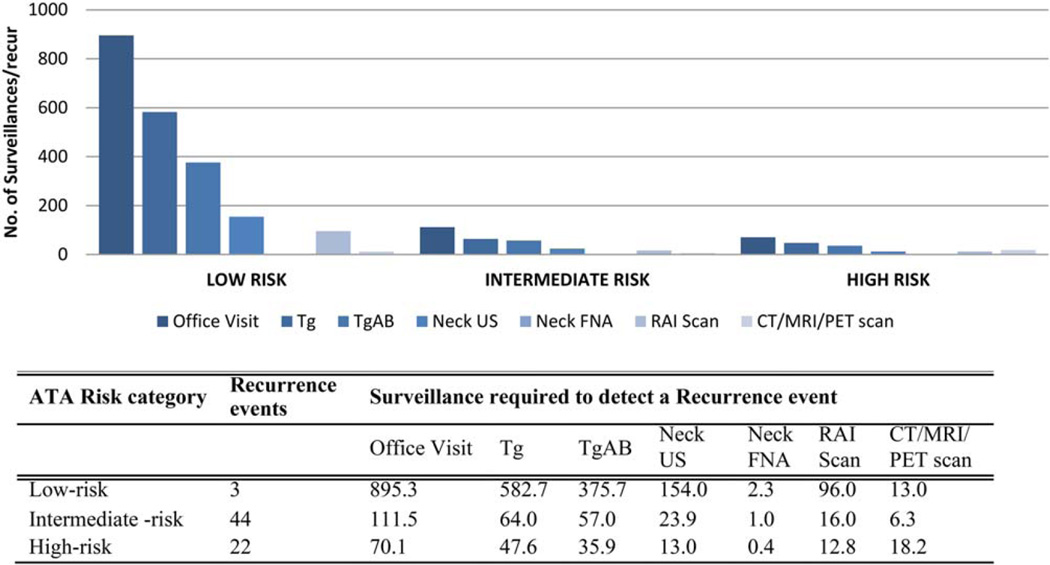

Surveillance Cost to Detect 1 Recurrence

Next, we calculated the cost of surveillance for each recurrence detected. At 3 years, there were 3, 44, and 22 recurrences in the low-, intermediate-, and high-risk categories, respectively; these values corresponded to recurrence rates of 0.8%, 7.8%, and 13.4% at 3 years. The cost of surveillance to detect 1 recurrence event was greatest for the low-risk cohort at US $147,819. The cost of recurrence detection for the intermediate- and high-risk categories was similar at US $22,434 and US $20,680, respectively (Table 3 and Fig. 3). The cost to detect 1 recurrence event in the low-risk category was 6.6 and 7.1 times greater than the cost in the intermediate- and high-risk categories.

Figure 3.

Surveillance ATA risk category in the first 3 years after thyroidectomy. Ab indicates antibody; ATA, American Thyroid Association; CT, computed tomography; FNA, fine-needle aspirate; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography; RAI, radioactive iodine; Tg, thyroglobulin; US, ultrasound.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses were performed to determine the effect on the cost per recurrence if the rates of recurrence and the rates of testing were different from what was observed in our cohort. If the rates of recurrence were 3 times higher (ie, 2.5%, 24%, and 40%), the magnitude difference between the 3 groups would be the same, but the cost to detect a recurrence would be $49,272 in the low-risk group (Table 4). If the rates of ultrasound use were 3 times higher for all groups (3.8%, 5.6%, and 5.3%), the magnitude difference between the low-risk group and the intermediate- and high-risk groups would again be the same, but costs would increase to $185,884 per recurrence for low-risk patients versus $28,332 for intermediate-risk patients and $23,904 for high-risk patients (Table 5).

TABLE 4.

Sensitivity Analysis 1: 3 Times the Number of Recurrences

| Surveillance Investigations in 36 mo, Total (per risk category) |

Surveillance Cost (US $) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATA Risk Category |

Patients. No. (%) |

Recurrences. No. (%) |

Office Visit |

Tg | Tg Ab | Neck US |

Neck FNA |

RAI Scan |

CT/MRI/ PET Scan |

Overall Cost |

Cost per Patient |

Cost per Recurrence |

| Low | 362 (33.3) | 9 (2.5) | 2686 (7.4) | 1748(4.8) | 1127(3.1) | 462 (1.3) | 7 (0.02) | 288 (0.80) | 39(0.11) | 443,456 | 1225 | 49,272 |

| Intermediate | 561 (51.6) | 132 (23.5) | 4907 (8.7) | 2817(5.0) | 2509 (4.5) | 1050 (1.9) | 43 (0.08) | 706 (1.26) | 275 (0.49) | 987,080 | 1760 | 7,477 |

| High | 164(15.1) | 66 (40.2) | 1542 (9.4) | 1047(6.4) | 789 (4.8) | 287 (1.8) | 8 (0.05) | 281 (1.71) | 401 (2.45) | 454,961 | 2774 | 6,893 |

| Total | 1087 | 207 | 9135 | 5612 | 4425 | 1799 | 58 | 1275 | 715 | 1,885,497 | 1735 | 9108 |

Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; ATA, American Thyroid Association; CT, computed tomography; FNA, fine-needle aspirate; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography; RAI, radioactive iodine; Tg, thyroglobulin; US, ultrasound.

TABLE 5.

Sensitivity Analysis 2: 3 Times the Number of Neck Ultrasounds

| Surveillance Investigations in 36 mo, Total (per risk category) |

Surveillance Cost (US $) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATA Risk Category |

Patients. No. (%) |

Recurrences. No. (%) |

Office Visit |

Tg | Tg Ab | Neck US |

Neck FNA |

RAI Scan | CT/MRI/ PET Scan |

Overall Cost |

Cost per Patient |

Cost per Recurrence |

| Low | 362 (33.3) | 3 (0.8) | 2686 (7.4) | 1748(4.8) | 1127(3.1) | 1386(3.8) | 7 (0.02) | 288 (0.80) | 39(0.11) | 557,653 | 1540 | 185,884 |

| Intermediate | 561 (51.6) | 44 (7.8) | 4907 (8.7) | 2817(5.0) | 2509 (4.5) | 3150(5.6) | 43 (0.08) | 706 (1.26) | 275 (0.49) | 1,246,619 | 2222 | 28,332 |

| High | 164(15.1) | 22 (13.4) | 1542(9.4) | 1047(6.4) | 789 (4.8) | 861 (5.3) | 8 (0.05) | 281 (1.71) | 401 (2.45) | 525,902 | 3206 | 23,904 |

| Total | 1087 | 69 | 9135 | 5612 | 4425 | 5397 | 58 | 1275 | 715 | 2,330,174 | 2143 | 35,306 |

Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; ATA, American Thyroid Association; CT, computed tomography; FNA, fine-needle aspirate; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography; RAI, radioactive iodine; Tg, thyroglobulin; US, ultrasound.

DISCUSSION

Thyroid cancer detection is continuing to rise with an increasing shift toward low-risk PTC in the United States. These trends coincide with a growing national interest in cost-effective health care practices. The aim of our study was to analyze the cost-effectiveness of PTC surveillance in the first 3 years after surgery for low-risk patients versus intermediate- and high-risk patients according to ATA categories. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the cost-effectiveness of posttreatment PTC disease surveillance. As anticipated, we found that the relative cost of the surveillance of higher risk patients to be greater than that of lower risk patients. The surveillance cost of intermediate- and high-risk PTC patients was 1.4 and 2.3 times greater than the surveillance cost of a low-risk patient. More importantly, the cost to detect 1 recurrence event in the low-risk category was 7 times greater than that for the high-risk category (low risk, US $147,819; high-risk, US $20,680). Changing the frequency of recurrence or the frequency of testing in sensitivity analyses led to different dollar amounts but did not eliminate the magnitude of the differences between the groups. Because of the epidemic proportional rise in the incidence of low-risk thyroid cancer, it is important to question this allocation of health resources to the surveillance of low-risk PTC patients after initial treatment.

What Are Current Management Recommendations?

The ATA management guideline recommendations for surveillance are based on a patient’s risk of disease recurrence. The 2009 and 2015 editions of the ATA guidelines recommend surveillance neck sonography 6 to 12 months after the operation and then periodically according to the patient’s risk of recurrent disease and Tg status.7 Much of the recommended long-term surveillance regimen is left to the individual physician’s interpretation and discretion. This is reflected in the wide variation in long-term thyroid cancer management strategies in a survey conducted among United States–based thyroid cancer clinicians. Of the 534 United States–based endocrine and nuclear medicine physicians surveyed, more than 45% reported that they would routinely follow American Joint Committee on Cancer stage I patients with an undetectable serum Tg level with surveillance ultrasound.12 However, despite management guidelines suggesting risk-stratified surveillance, there is significant variation in the surveillance strategies being performed.

Why It Is Important to Address Low-Risk PTC Surveillance Practices?

The estimated annual cost of thyroid cancer to the US health care system is expected to increase from $1.4 billion in 2010 to $2.4 billion in 2019 with current practice standards.5 The incidence of thyroid cancer increased nearly 3-fold between 1975 and 2009, and almost all of this was due to an increase in PTC. Furthermore, this increase is dominated by low-risk PTC cases, many of which are papillary microcarcinomas. In 2009, 39% of all new thyroid cancer diagnoses were 1 cm or smaller, whereas only 25% of cases were 20 years ago.1 Because of these well-documented epidemiological trends of increasing low-risk PTC in conjunction with stable disease mortality, the reservoir of thyroid cancer survivors in the community will continue to increase at an exponential rate. Medical resources associated with disease surveillance for these thyroid cancer survivors will further increase. A recent Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Medicare database study demonstrated a trend toward increased use of postdiagnostic imaging modalities across all risk categories over recent decades.13 Although thyroid cancer is a disease with a relatively low clinical recurrence and death burden, the economic burden of the disease is not insignificant and continues to grow. A review of surveillance practices to improve cost-effectiveness in low-risk PTC could significantly curb the rising costs of thyroid cancer management.

The increase in low-risk thyroid cancer is occurring during a time of increasing concern over health care spending. In 2012, US national health expenditures were estimated at $2.8 trillion, or 18% of the gross domestic product, the highest of any developed country. Cancer care accounted for an estimated $124.6 billion in medical care.14 It is anticipated that by 2022, national health spending will account for nearly one-fifth of the US economy.15 The escalation in health care costs is a growing burden on society and poses a great challenge to all aspects of government and medicine. As physicians, we have a responsibility to recognize the significance of the situation, encourage open discussion and research, and move toward more sustainable and cost-effective care.

What Is the Physician’s Role and Position on Cost-Effective Practices?

In general, most physicians are aware of the costs of health care. However, studies suggest that physicians often hold more conflicted views about the implementation of cost-effective health care delivery. In a cross-sectional survey mailed to more than 3800 US physicians (response rate, 65%), it was found that most physicians agreed that “trying to contain costs is the responsibility of every physician” and that “doctors need to take a more prominent role in limiting use of unnecessary tests.” The same group of physicians disagreed with the statement that they “should sometimes deny beneficial but costly services to certain patients because resources should go to other patients that need them more.”16 Similar inconsistencies are demonstrated in a survey of US and Canadian oncologists. When directly asked how much benefit a new drug would need to provide to justify its cost and warrant its use, the majority of oncologists agreed that less than $100,000 per life-year gained would be worthwhile therapy. However, when this was rephrased in the context of a hypothetical patient case, the oncologists endorsed a cost as high as $250,000 per life-year gained.17 This inconsistency is likely a reflection of the tension between the fundamental principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence (to individual patients) and justice (to society as a whole). When this is applied to PTC surveillance, the low cost-effectiveness of surveillance in low-risk PTC patients suggests that as a subspecialty we have tipped too far toward beneficence for the individual, low-risk patient and away from concerns about justice for non–low-risk patients.

What Evidence Is There for Surveillance of Low-Risk Patients?

Commonly, the thyroid cancer recurrence rate is quoted at 30%. This outcome was reported by Mazzaferri et al18,19 for patients treated 30 to 40 years ago, most of whom had clinically palpable primary or nodal disease at the time of presentation. Our subspecialty’s vigilance for surveillance in PTC is still deeply influenced by the outcomes of Mazzaferri et al’s publications of thyroid cancer outcomes. Many recent publications have demonstrated substantially lower recurrence rates of 3% to 10%.10,20–22 Durante et al20 followed 312 consecutive stage T1aN0M0 patients with classic PTC, and with a median follow-up of 6.7 years, the group reported no structural disease recurrence events and no disease-specific deaths.20 Our data, along with the recent literature, clearly demonstrate that recurrence rates for low-risk PTC are very low. Several publications in recent years have similarly recognized a need for reduced PTC surveillance23 based on the risk of recurrence.24 The challenge now is to recalibrate surveillance regimes to reflect modern recurrence outcomes for more cost-effective surveillance practices.

Limitations

It is important to note that our study has several limitations. Because of its single-institution and retrospective nature, our study is susceptible to a selection bias due to physician management and the large number of patients excluded from the analysis. We report the results from an institution with a high volume of thyroid cancer and decades of experience in the management of PTC. Our experience is characterized by a very low structural recurrence rate. This is a limitation of the study, and consequently, our results may not be translatable to the wider community. The threshold for instigating surveillance investigations is also likely to be different between centers. Physicians at our center have previously advocated for a higher threshold before biopsy of suspicious ultrasound findings.25 This would also influence the cost-effectiveness of surveillance practices if our findings were applied to other centers. Second, surveillance practices evolved during the inclusion period. Current surveillance practices are presented in Table 6.26 The cost-effectiveness data presented are, therefore, averaged for 2000 to 2010. A prospectively conducted, multiinstitution study would better ensure uniformity of the patient cohort as well as subsequent management.

TABLE 6.

Postoperative Surveillance Strategy Based on the American Thyroid Association Risk Category

| 6 mo | 12 mo | 18 mo | 24 mo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thyroglobulin | All | All | All | All |

| Neck ultrasound | – | All | – | All |

| Diagnostic RAI scan | – | – | Intermediate/ high risk |

– |

| CT/MRI | – | High risk | – | High risk |

| PET scan | – | High risk | – | High risk |

Abbreviations: All, low, intermediate, and high risk; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography; RAI, radioactive iodine.

The cost to detect a recurrence in a low-risk patient is more than 7 times greater than the cost for a high-risk papillary thyroid cancer patient. It is difficult to justify this allocation of resources, and surveillance strategies for the low-risk group should be reviewed.

Other limitations are related to the degree to which we might be underestimating the true cost of surveillance practices. For example, some patients had additional surveillance investigations performed outside Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, often for personal or logistic reasons. It is not possible to know how many patients or which additional surveillance investigations were performed. In addition, the data used for costs are from CMS reimbursement schedules, and those costs may be below the costs and charges for patients with private insurance. Finally, we have not accounted for the costs and harms of surveillance practices, which are hard to measure in dollars (eg, days of work missed and harm from needle biopsy or contrast imaging). Ultimately, the question of whether or not our data can be extrapolated to the general population should be explored by an analysis of the incidence of disease recurrence and surveillance practices at other high-volume thyroid surgery centers.

In summary, we have demonstrated that the Medicare reimbursement cost to detect a recurrence event in a low-risk patient (ATA category) is more than 6 times greater than the cost to detect a recurrence event in a high-or intermediate-risk patient at US $147,819. We acknowledge, of course, that this dollar amount could not possibly be representative of the costs of surveillance nationally. Regardless, our findings raise important questions regarding the allocation of health care resources and the ways in which surveillance of low-risk PTC patients should be tailored to maximize effectiveness. Currently, in this cohort, we believe that the cost of surveillance for PTC patients is unjustifiably greater for low-risk patients. In light of the continued rise in the incidence of low-risk PTC, surveillance costs will continue to increase. We cannot comprehensively resolve this issue on the basis of a single institution’s experience. We, therefore, encourage other centers to review the cost-effectiveness of their surveillance practices for their own low-risk PTC patients. We hope to promote discussion on appropriate PTC surveillance practices that reflect contemporary recurrence rates so that we can improve the cost-effectiveness of thyroid cancer management.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SUPPORT

No specific funding was disclosed.

Footnotes

Ian Ganly contributed to the study concept and design. Laura Y. Wang, Benjamin R. Roman, Jocelyn C. Migliacci, Frank L. Palmer, and Ian Ganly contributed to the statistical analysis. Laura Y. Wang, Benjamin R. Roman, Jocelyn C. Migliacci, Frank L. Palmer, and Ian Ganly contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. Laura Y. Wang, Benjamin R. Roman, and Ian Ganly contributed to the drafting of the article. Jatin P. Shah, Ashok R. Shaha, Snehal G. Patel, and R. Michael Tuttle contributed to the critical revision of the article. Ian Ganly and Laura Y. Wang had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors made no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Davies L, Welch H. Current thyroid cancer trends in the United States. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140:317–322. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies L, Welch HG. Thyroid cancer survival in the United States: observational data from 1973 to 2005. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136:440–444. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blomberg M, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Andersen KK, Kjaer SK. Thyroid cancer in Denmark 1943–2008, before and after iodine supplementation. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2360–2366. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L, Palmer F, Thomas D, et al. Preoperative neck ultrasound in clinical node negative differentiated thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:3686–3693. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, Schechter RB, Shih YC, et al. The clinical and economic burden of a sustained increase in thyroid cancer incidence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:1252–1259. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young S, Harari A, Smooke-Praw S, Ituarte P, Yeh M. Effect of reoperation on outcomes in papillary thyroid cancer. Surgery. 2013;154:1354–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, et al. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19:1167–1214. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed November 1, 2014];Physician Fee Schedule Search. http://www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/search/search-criteria.aspx.

- 9.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed November 1, 2014];Clinical Lab Fee Schedule. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/clinlab.html.

- 10.Tuttle RM, Tala H, Shah J, et al. Estimating risk of recurrence in differentiated thyroid cancer after total thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine remnant ablation: using response to therapy variables to modify the initial risk estimates predicted by the new American Thyroid Association staging system. Thyroid. 2010;20:1341–1349. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitoia F, Bueno F, Urciuoli C, Abelleira E, Cross G, Tuttle RM. Outcomes of patients with differentiated thyroid cancer risk-stratified according to the American Thyroid Association and Latin American Thyroid Society risk of recurrence classification systems. Thyroid. 2013;23:1401–1407. doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haymart MR, Banerjee M, Yang D, et al. Variation in the management of thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2001–2008. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiebel JL, Banerjee M, Muenz DG, Worden FP, Haymart MR. Trends in imaging after diagnosis of thyroid cancer. Cancer. 2015;121:1387–1394. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Cancer Institute. [Accessed June 2015];Cancer trends progress report—2011/2012 update. http://progressreport.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/archive/report2011.pdf.

- 15.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed November 15, 2014];National health expenditure projections 2012–2022. http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/National-HealthExpendData/downloads/proj2012.pdf.

- 16.Tilburt JC, Wynia MK, Sheeler RD, et al. Views of US physicians about controlling health care costs. JAMA. 2013;310:380–388. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ubel PA, Berry SR, Nadler E, et al. In a survey, marked inconsistency in how oncologists judged value of high-cost cancer drugs in relation to gains in survival. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:709–717. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazzaferri EL, Jhiang SM. Long-term impact of initial surgical and medical therapy on papillary and follicular thyroid cancer. Am J Med. 1994;97:418–428. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazzaferri EL, Kloos RT. Clinical review 128: current approaches to primary therapy for papillary and follicular thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1447–1463. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.4.7407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durante C, Attard M, Torlontano M, et al. Identification and optimal postsurgical follow-up of patients with very low-risk papillary thyroid microcarcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4882–4888. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durante C, Montesano T, Torlontano M, Attard M, Monzani F, Tumino S. Papillary thyroid cancer: time course of recurrences during postsurgery surveillance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:636–642. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito Y, Higashiyama T, Takamura Y, Kobayashi K, Miya A, Miyauchi A. Prognosis of patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma showing postoperative recurrence to the central neck. World J Surg. 2011;35:767–772. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0924-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu JX, Beni CE, Zanocco KA, Sturgeon C, Yeh MW. Cost-effectiveness of long-term every three-year versus annual postoperative surveillance for low-risk papillary thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2015;25:797–803. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durante C, Costante G, Filetti S. Differentiated thyroid carcinoma: defining new paradigms for the post-operative management. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20:R141–R154. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rondeau G, Fish S, Hann LE, Fagin JA, Tuttle RM. Ultrasonographically detected small thyroid bed nodules identified after total thyroidectomy for differentiated thyroid cancer seldom show clinically significant structural progression. Thyroid. 2011;21:845–853. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Momesso DP, Tuttle RM. Update on differentiated thyroid cancer staging. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2014;43:401–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]