Abstract

Background:

Dentin hypersensitivity (DH) is an age old complaint with a great number of treatment modalities, but none of these are totally effective till date. Lasers being one of the latest treatment options in periodontics, a study was conducted to test the efficacy of diode laser (DL) in DH alone and in comparison with 5% sodium fluoride (NaF) varnish.

Aim:

The aim of the present study was to compare the effectiveness of 5% topical NaF varnish and 980 nm gallium aluminum arsenide (GaAlAs) DL alone and combination of 5% NaF + 980 nm GaAlAs DL in the management of DH.

Materials and Methods:

The study was conducted on 120 teeth in thirty patients with DH assessed by tactile and air blast (AB) stimuli measured by visual analog scale (VAS). Teeth were randomly divided into Group 1 (P) placebo-treated control group, Group 2 (NaF) treated by 5% NaF varnish, Group 3 (DL) treated with 980 nm DL, and Group 4 (NaF + DL) treated with both 5% NaF varnish and 980 nm DL (combination group).

Results:

There was a significant reduction in DH. The VAS reduction percentages were calculated, and there was a significant decrease in DH above all in G4 (NaF + DL) than G3 (DL) and G2 (NaF).

Conclusion:

Even though all the three groups (2, 3, and 4) showed improvement in terms of DH reduction, 5% NaF varnish with DL showed the best results among all the groups.

Key words: Dentin hypersensitivity, gallium aluminum arsenide diode laser, pain measurement, sodium fluoride varnish

INTRODUCTION

Dentin hypersensitivity (DH) is an exaggerated response to sensory stimuli that usually causes no response in a normal, healthy tooth.[1] It is characterized by short, sharp pain arising from exposed dentin in response to stimuli, typically thermal, evaporative, tactile, osmotic, or chemical, and which cannot be ascribed to any other form of dental defect or pathology.[2,3]

Various theories proposed for DH are:

Transducer theory

Gate control theory

Direct receptor mechanism or direct stimulation theory or modulation theory

Hydrodynamic theory.

The hydrodynamic theory is the most widely accepted hypothesis to explain how stimuli applied on the dentin surface influence nerve fibers,[2,4] thus resulting in pain impulses.[5,6]

Hydrodynamic theory

Fish in 1927 observed the interstitial fluid of the dentin and pulp, referring to it as the “dental lymph.” He postulated that the flow of this fluid could take place in either an outward or inward direction depending on the pressure vibrations in the surrounding tissues. Kramer in 1955 postulated the “hydrodynamic theory” as follows. The dentinal tubules contain fluid or semi-fluid materials and their walls are relatively rigid. Peripheral stimuli are transmitted to the pulp surface by movement of this column of semi-fluid material within the tubules. However, he was not convinced that the theory of dentinal fluid movement was responsible for the transmission of pain of the hypersensitive dentin. Later, Brainstorm et al., 1962, proposed this hydrodynamic theory to explain the mechanism for the hypersensitivity associated with exposed dentin. The hypothesis was that movement of fluid in the dentinal tubules was capable of stimulating the pulpal nerve tissue (plexus of Raschkow). Therefore, root surface areas with an increased number of exposed (or open) dentinal tubules should have an increased potential for dentin fluid flow and hence increased DH.

The most commonly used agents in the treatment of DH are classified as anti-inflammatory agents, protein precipitants (formaldehyde, silver nitrate, and strontium chloride), tubule-occluding agents (potassium oxalate, calcium hydroxide, potassium nitrate, and sodium fluoride [NaF]), tubule sealants (resins and adhesives), and miscellaneous (lasers).[7] Till date, numerous agents have been tried to eliminate this unpleasant symptom, in the form of mouthwashes, dentifrices, gel, ionic exchange gadgets (iontophoresis), etc. However, none of these agents are capable of delivering the drug constantly for long periods and requires frequent revisits by patients or may take long time for providing relief. Clinical trials have supported different approaches, and the results have been contradictory.[8,9]

Several studies have described a synergistic action of lasers with NaF.[10,11,12,13,14,15] Hence, the aim of the present study was to clinically evaluate the efficacy of 5% NaF varnish and 980 nm diode laser (DL) irradiation alone and in comparison with the combination of NaF varnish and 980 nm DL in the management of DH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

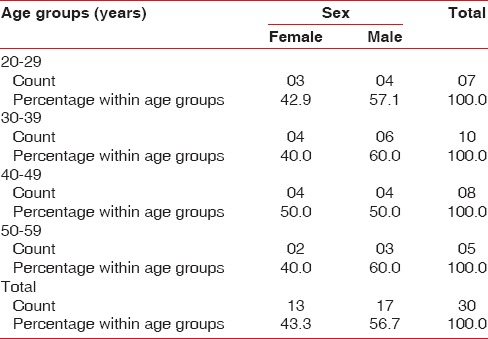

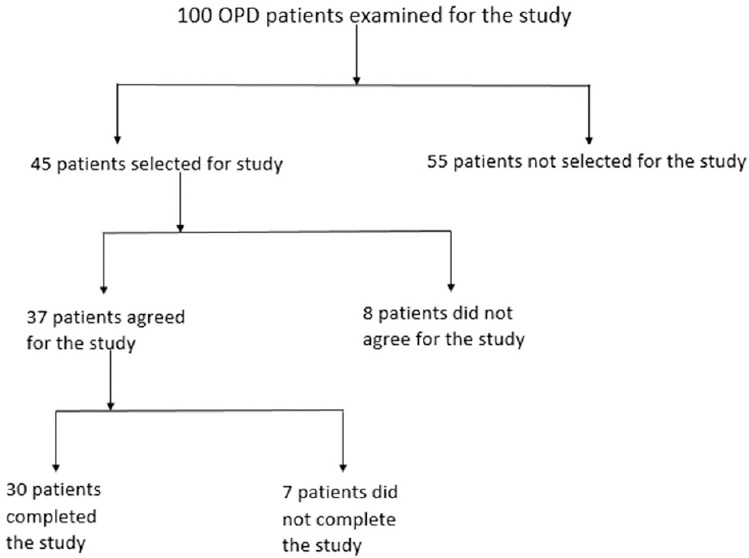

A total of 120 teeth from thirty patients were selected from the Department of Periodontics with moderate or severe DH according to the visual analog scale (VAS) [Table 1 and Figure 1].[16]

Table 1.

Demographic data

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the patients

Criteria for selection

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were patients in good systemic health, good oral hygiene, and clinically demonstrable DH teeth, specifically canines and premolars, which were reliable in their response to test measurements.[17]

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were patients with any systemic or psychological diseases, constant use of analgesic, anti-inflammatory drugs, or allergic responses to dental products, carious lesions, defective restorations, fractures, prosthesis or orthodontics appliances, periodontal pockets, mobility, or evidence of pulpits. In addition, those who have used any desensitizing agents or undergone any periodontal surgery in the last 6 months were excluded from the study.

Participants were informed about the purpose of the investigation and signed an appropriate informed consent form.

Scaling and polishing was done for all the patients 1 week before the study and subjects were instructed not to use any other desensitizing agents during the study. All patients were taught modified Stillman technique and were instructed to use the same with nondesensitizing toothpastes and soft bristle tooth brushes.

The equipment and the materials used in the study included NaF varnish. Each ml contains NaF I.P 50 mg equivalent to 22.6 mg of fluoride in slow release form, 22,600 ppm of fluoride, 980 nm (975 nm ± 10 nm) DL applied at 2 watt power in continuous wave mode, i.e., 2W/CW (166J/cm2).

Assessment of hypersensitivity

Visual analog scale

A VAS is a line which is 10 cm in length, the extremes of which represent the limits of pain, a patient might experience from an external stimulus (no pain at one end and severe pain at the other end of the line). Patients were asked to place a mark on the 10 cm line which indicated the intensity of their DH.

The degree of sensitivity was determined for each tooth in response to tactile (Hu Friedy dental explorer no. 11/12 DE)[18] and air blast (AB)[16] stimuli. The tactile stimulus with explorer was applied under light manual pressure on facial surface in the mesiodistal direction on the cervical area of the tooth [Figure 2].[18] The AB was performed with an air syringe (air pressure 25–28 psi) of the dental unit at normal room temperature for 1 s at a distance of 1 cm from the tooth surface [Figure 3]. DH was assessed by patient's indication of the severity of pain related to each tooth immediately after each stimulus, according to VAS.[16] The sensitivity patterns were recorded at baseline, 24 h, 1 week, 1 month, and 2 months. The order in which the teeth were evaluated within each subject was maintained at each visit.

Figure 2.

Tactile stimulation assessment of dentinal hypersensitivity using an explorer

Figure 3.

Air blast stimulation for the assessment of dentinal hypersensitivity using dental three-way syringe

Treatment modalities

Patients with DH in all four quadrants were selected. In each quadrant, the most sensitive tooth was selected for recording the VAS score. A total of 120 teeth were selected with one tooth in each quadrant. For equal allocation of the teeth into four groups, namely G1 (P), G2 (NaF), G3 (DL), and G4 (NaF + DL) according to the desensitizing treatment under study, randomization sequence was generated using a table of random numbers.

Group 1 (P): Placebo-treated control group - after proper isolation, distilled water was applied by means of a cotton swab for 20 s.

Group 2 (NaF): After isolation, a thin film of 5% NaF varnish was painted on the sensitive surface with a disposable microbrush as per the manufacturer's instructions for 60 s [Figure 4]. The cotton roll was removed to allow saliva or moisture to set the varnish.

Figure 4.

Application of sodium fluoride varnish with applicator tip on the cervical portion of the tooth

Group 3 (DL): 980 nm DL was applied at 2 W power in a continuous wave mode on the test tooth surface. It was applied in a no contact mode using a fiber of 320 micron diameter held perpendicular to the irradiated surface at a distance of 1 mm. Each area was irradiated twice for 20 s [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Irradiation of the cervical portion of the tooth with diode laser tip

Group 4 (NaF + DL): Treated using both NaF varnish and DL at the same parameters of Group 2 and 3. The NaF varnish was left on the tooth surface for 60 s before the irradiation.

Statistical analysis

The mean values of the clinical parameters were calculated for all the groups according to the different stimuli. Scores obtained at 24 h through 2 months were evaluated using ANOVA repeated measure test and with the paired t-test. The corresponding P values were obtained at 29° of freedom. In this study, the level of significance was taken at 5%, i.e., P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 120 teeth in thirty patients completed the 2-month study period. Complications such as detrimental pulpal effects or allergic reactions were not observed during this period. All teeth remained vital after treatment, with no reported adverse reactions or clinically detectable complications.

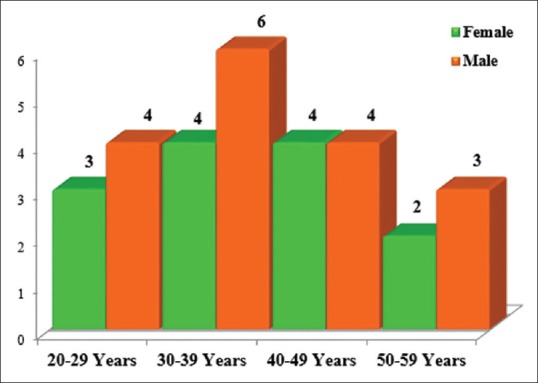

There was an equal distribution of sexes in 40–49 years age group and there were more number of males as compared to females in remaining (20–29, 30–39, and 50–59 years) age groups, but the difference seen in these age groups was not statistically significant. Hence, the age and sex distribution was comparable in this study [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Age and sex distribution

No difference was found at each interval for control group (placebo) for all the sites analyzed in the study.

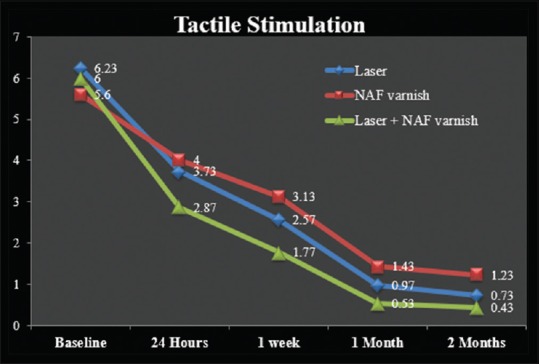

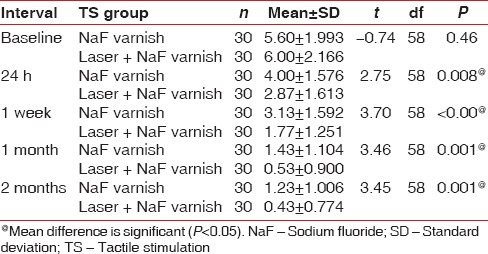

Tactile stimulation (within-group comparison)

Sodium fluoride varnish

At baseline, the mean score was 5.60 ± 1.993, followed by a gradual decrease in the mean tactile stimulation (TS) at 24 h (4.00 ± 1.576), 1 week (3.13 ± 1.592), 1 month (1.43 ± 1.104), and 2 months (1.23 ± 1.006). The difference found from baseline to 2 months was statistically significant [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Mean change in tactile stimulation between the groups under study

Diode laser

At baseline, the mean score was 6.23 ± 2.501, there was a gradual decrease in the mean TS in 24 h (3.73 ± 1.946), 1 week, (2.57 ± 1.612), 1 month (0.97 ± 1.098), and 2 months (0.73 ± 0.944). The difference found from baseline to 2 months was statistically significant (P = 0.001) [Figure 7].

Combination (sodium fluoride + diode laser)

At baseline, the mean score was 6.00 ± 2.166, there was a gradual decrease in the mean TS in 24 h (2.87 ± 1.613), 1 week, (1.77 ± 1.251), 1 month (0.53 ± 0.900), and 2 months (0.43 ± 0.774), the difference found from baseline to 2 months was statistically significant.

There was no significant difference in the mean values of the TS of three groups (NaF varnish, laser, and NaF varnish + laser) at baseline level. However, there was a gradual decrease in the mean values of TS of these groups at 24 h, 1 week, 1 month, and 2 months level, and this difference found was highly significant [Figure 7].

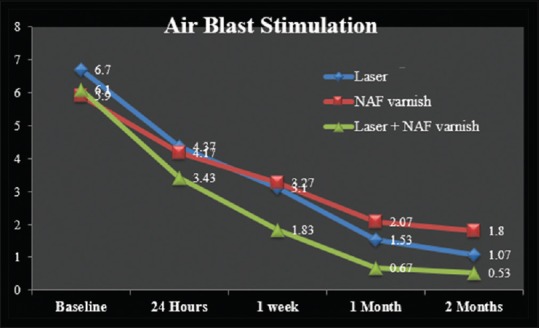

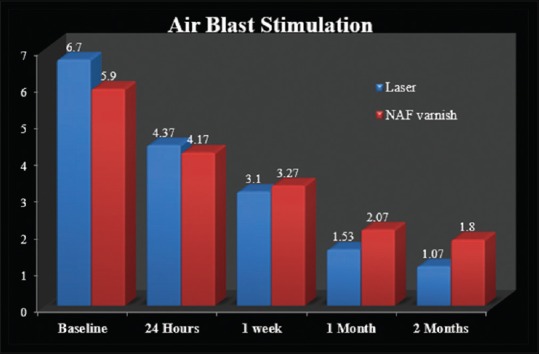

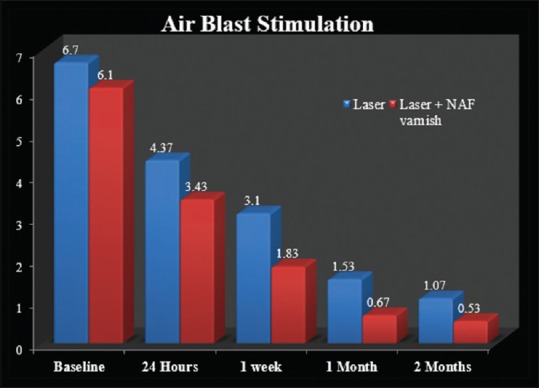

Air blast stimulation (within-group comparison)

Sodium fluoride varnish

At baseline, the mean difference was 6.70 ± 2.103, there was a gradual decrease in the mean AB stimulation, at 24 h (4.17 ± 1.487), 1 week (3.27 ± 1.507), 1 month (2.07 ± 0.740), and 2 months (1.80 ± 0.925), the mean difference found from baseline to 2 months was statistically significant [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

Mean change in air blast stimulation between the groups under study

Diode laser

At baseline, the mean difference was 5.90 ± 1.900, there was also a gradual decrease in the mean AB stimulation, at 24 h (4.37 ± 1.650), 1 week (3.10 ± 1.626), 1 month (1.53 ± 1.042), and 2 months (1.07 ± 0.907), the mean difference found from baseline to 2 months was statistically significant [Figure 8].

Combination (sodium fluoride + diode laser)

There was a gradual decrease in the mean values of AB stimulation from baseline (6.70 ± 1.826) to 24 h (3.43 ± 1.176), 1 week (1.83 ± 1.206), 1 month (0.67 ± 0.711), and 2 months (0.53 ± 0.681). The mean difference found from baseline to 2 months was statistically significant [Figure 8].

There was no significant difference in mean values in the AB stimulation between the three groups (NaF varnish, laser, and laser + NaF varnish) at baseline and 24 h level. However, there was a gradual decrease in mean values in the AB stimulation of these groups at 1 week, 1 month, and 2 months level, and this difference found was highly significant.

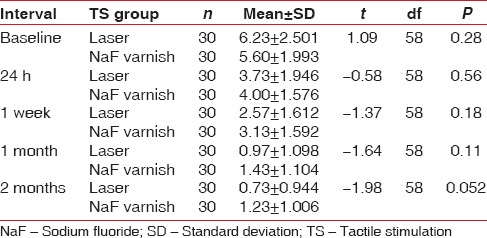

Tactile stimulation – between-group comparisons

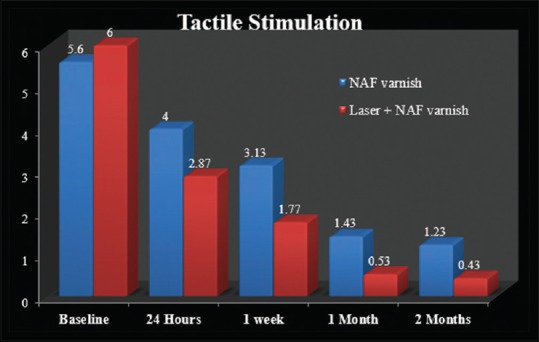

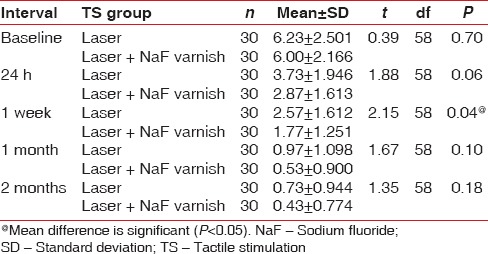

Tables 2–4 show the comparison of mean difference of TS between three groups (NaF varnish, laser, and laser + NaF varnish) at various intervals [Figures 9–11].

Table 2.

Mean change in tactile stimulation between laser and sodium fluoride varnish

Table 4.

Mean change in tactile stimulation between sodium fluoride varnish and combination group (sodium fluoride + diode laser)

Figure 9.

Comparison of mean change in tactile stimulation between the groups (laser and sodium fluoride varnish)

Figure 11.

Comparison of mean change in tactile stimulation between groups (sodium fluoride and laser + sodium fluoride varnish)

Table 3.

Mean change in tactile stimulation between laser and combination group (sodium fluoride + diode laser)

Figure 10.

Comparison of mean change in tactile stimulation between groups (laser and laser + sodium fluoride varnish)

At baseline level, there was no significant mean difference found between any of these three groups: NaF varnish and DL; P = 0.28, NaF varnish and combination group; P = 0.46, and laser and combination group; P = 0.70.

At 24 h, among the three groups (NaF varnish and DL; P = 0.56, NaF varnish and combination group; P = 0.008, laser and combination group; P = 0.06), significant results were seen in comparison with NaF varnish and combination treatment, where combination group has a statistically significant mean difference when compared to NaF varnish.

At 1 week interval, among the three groups (NaF varnish and DL; P = 0.18, NaF varnish and combination; P = 0.001, laser and combination; P = 0.04), statistically significant difference was seen in comparison with laser and combination treatment, and highly significant result was seen with comparison between varnish and combination treatment (P = 0.001).

At 2-month interval, there was a significant mean difference between laser and NaF varnish (P = 0.05) as well as between laser + NaF varnish and NaF varnish group (P = 0.001) for TS.

Hence, overall laser + NaF varnish group had less TS as compared with laser and NaF varnish group.

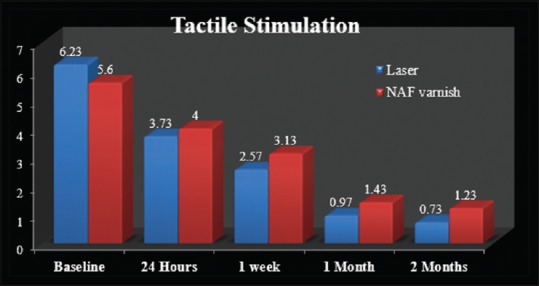

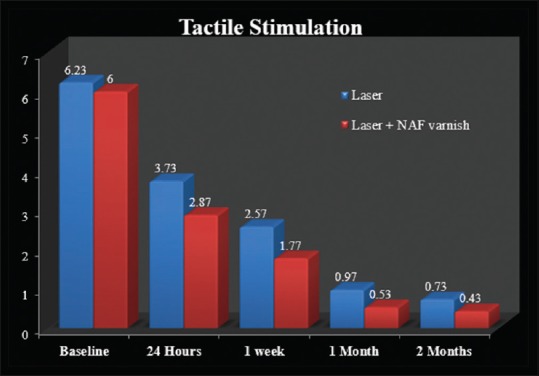

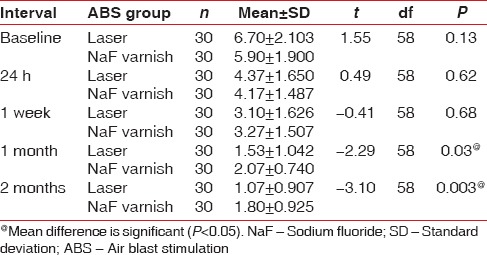

Air blast stimulation (within-group comparison)

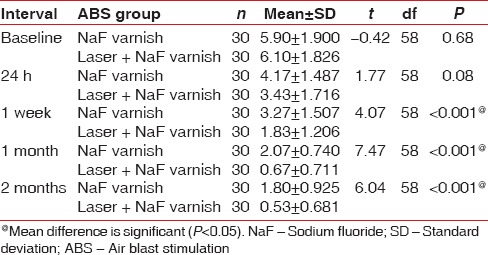

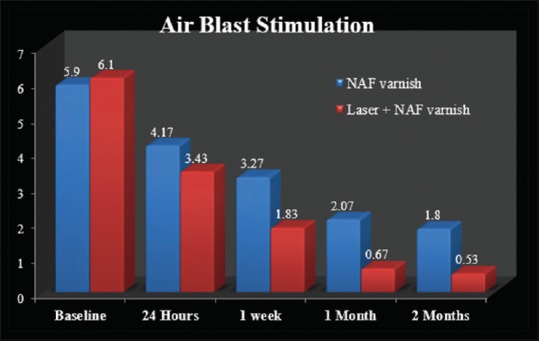

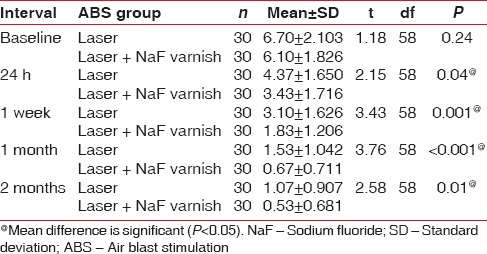

Tables 5–7 show the intergroup comparison of mean difference of AB stimulation between three groups (Laser, NaF varnish, and laser + NaF varnish) at various intervals [Figures 12–14].

Table 5.

Mean change in air blast stimulation between laser and sodium fluoride

Table 7.

Mean change in air blast stimulation between sodium fluoride and combination group (sodium fluoride + diode laser)

Figure 12.

Comparison of mean change in air blast stimulation between groups (laser and sodium fluoride varnish)

Figure 14.

Comparison of mean change in air blast stimulation between group (sodium fluoride and laser + sodium fluoride)

Table 6.

Mean change in air blast stimulation between laser and combination group (sodium fluoride + diode laser)

Figure 13.

Comparison of mean change in air blast stimulation between groups (laser and laser + sodium fluoride)

At baseline level, there was no significant mean difference found among any of these three groups (NaF varnish and DL; P = 0.13, NaF varnish and combination group; P = 0.68, laser and combination group; P = 0.24), whereas there was statistically significant mean difference between laser group and combination group at 24 h interval (P = 0.04).

Statistically no significant mean difference was seen at 1-week interval in NaF varnish and DL (P = 0.68), but statistically significant mean difference was seen at 1-week interval in NaF varnish and combination group (P = 0.001), laser and combination group (P = 0.001).

At 1-month and 2-month interval, there was a significant mean difference between laser and laser + NaF varnish group, between NaF varnish and laser + NaF varnish group as well as laser and NaF varnish group.

Hence, laser group had lesser AB stimulation response as compared to NaF group while AB stimulation for laser + NaF varnish was the least as compared to NaF varnish and laser group alone.

In intragroup comparison, each group showed a statistical significant reduction in DH from baseline to 2 months. In addition, in intergroup comparison, for TS and AB stimulation, compared to baseline, there was a significant mean difference between laser, NaF, and laser + NaF at the end of 2 months. Overall, laser + NaF varnish group had less tactile and AB stimulation as compared to laser and NaF group alone.

The results showed a significant decrease in DH in all the three groups. The three groups showed a significant reduction in sensitivity in a short time (24 h), which did not occur with the placebo group. Using repeated measures ANOVA test at 24 h, 1 week, 1 month, and 2 months values as dependent variables and baseline values as covariates, the TS and AB stimulation tests demonstrated a significant difference between groups and a significant difference over the 2-month study period. There was also a significant difference in the interaction of groups with time, indicating a superior performance of combination group (NaF and DL), followed by DL, and finally the NaF varnish group. Furthermore, from the mean percentage reduction in each sensitivity measure from baseline to 24 h, 1 week, 1 month, and 2 months, there was a reduction in sensitivity for all groups for all sensitivity measures.

DISCUSSION

Although multiple treatments are proposed for DH, still no gold standard for the treatment of DH is available today and therefore it remains a chronic dental problem. A possible elimination of painful symptoms resulting from the DH seems to be directly related to the interruption of stimuli transmission to the nerve endings of odontoblast processes by reducing the fluid movement inside the dentinal canalicules through the narrowing or occlusion of tubules openings.[19]

Cervical DH has multifactorial etiology and generally more than one factor is found to be associated with this painful manifestation. Therefore, more than one treatment method should be associated to desensitize the dentin to satisfactory levels.

Conventional therapies for the treatment of DH comprehend the topical use of desensitizing agents, either professionally or at home such as protein precipitants, tubule-occluding agents,[20] tubule sealants, and recently, lasers.[21]

Any treatment that reduces the dentin permeability must diminish dentin sensitivity. The occlusion of dentinal tubules leads to reduction of dentin permeability and proportionally, also decreases the degree of DH.[22]

According to the hydrodynamic theory, the effectiveness of dentin desensitizing agents is directly related to their capacity to promote the sealing of the dentinal canaliculi.[23]

Several studies [11,12,13] describe a synergistic action of lasers in association with desensitizing agents. For this reason, if laser device is used in addition to a conventional desensitizing agent, the latter remains above the tooth surface for 60 s before the irradiation.

In the present study, no difference was found at each interval for control group (placebo) for all the sites analyzed in the study.

The gradual reduction in stimuli in Group 2 (NaF) may be attributed to the reaction that occurs between NaF and calcium ions of dentinal fluid and that leads to the formation of calcium fluoride crystals, which are deposited on the dentinal tubule openings. In addition, the patency of sensitive dentin interferes with the action of therapeutic tubule-occluding agents and demands a longer treatment, as the number and width of dentinal tubules in hypersensitive-exposed areas have been shown to be higher than in normal dentin, which is in accordance with the study conducted by Liu and Lan, 1994.[24] The reduction in mean TS and AB stimulation with NaF varnish is also in accordance with a study done by Ritter et al., 2006[25] who reported distinct reduction in DH when observed between initial measurements and 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-week examination periods of NaF varnish and dentin bonding agents.

For Group 3 (DL) compared to baseline, there was a gradual decrease in the mean tactile and AB stimulation in 24 h, 1 week, 1 month, and 2 months. This is in accordance with a study by Matsumoto et al.[26] which observed 85% improvement in teeth treated with laser, Yamaguchi et al.[27] observed an effective improvement index of 60% in the group treated with laser compared to the 22.2% of the control nonlased group, and Kumazaki et al.[28] showed an improvement of 69.2% in the group treated with laser compared to 20% in the placebo group.

The power parameter used in this study was 2 W/CW which was agreeable by a study done by Liu et al.[29] This study demonstrated that 2 W/CW (166 J/cm2) was a suitable parameter for a 980-nm DL to seal dentinal tubules without excess melting of the dentin. The maintenance of this analgesic state of the dentin comes from sealing of dentinal tubule, which impedes the internal communication of the pulp with external oral fluids.[21,30]

Group 4 (NaF + DL) showed a definitive reduction for both the stimuli. Several studies [10,11,14,15] describe a synergistic action of lasers in association with desensitizing agents. In fact, the laser system can favor the permanence of the desensitizer for longer time than when they are used alone. Significant improvements in sensitivity was registered in all groups. DH showed a marked reduction compared to the other groups. Results are also in accordance with the study done by Umberto et al.,[31] they compared the effectiveness of 980 nm DL alone and with topical NaF gel (NaF) and concluded that DL is a useful device for DH treatment if used alone and mainly if used with NaF gel. Kumar and Mehta [11] in their clinical trial found a dramatic reduction in the VAS and cold AB index after the combination use of fluoride and laser together.

Lower reduction values were registered in Group 2 (NaF) compared to Group 4 (NaF + DL). It is probable that the better performance of combined treatment was due to the higher NaF varnish adhesion to the dentinal tubules when combined with laser energy.

Therefore, based on the results of this study, it is clear that 5% NaF varnish, DL, and the combination of 5% NaF varnish and laser, all three are able to improve the DH condition. However, combination of laser and NaF varnish yields better results in terms of decrease in hypersensitivity.

The limitations of the present study

Longer observational periods would have enhanced the ability for the present study to detect differences between active and placebo groups and to confirm the stability and sustainability of clinical outcomes

Although the sample size selected for the present study showed significant results, a larger sample size would have been desirable.

CONCLUSION

The study concluded that the combined use of 5% NaF varnish and 980 nm DL resulted in significant reduction in the severity of DH. The therapeutic effect of this combination is better than the application of laser alone or fluoride varnish alone.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Orchardson R, Gangarosa LP, Sr, Holland GR, Pashley DH, Trowbridge HO, Ashley FP, et al. Dentine hypersensitivity-into the 21st century. Arch Oral Biol. 1994;39(Suppl):113S–9S. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(94)90197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartold PM. Dentinal hypersensitivity: A review. Aust Dent J. 2006;51:212–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orchardson R, Gillam DG. Managing dentin hypersensitivity. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:990–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walters PA. Dentinal hypersensitivity: A review. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005;6:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brännström M, Aström A. The hydrodynamics of the dentine; its possible relationship to dentinal pain. Int Dent J. 1972;22:219–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hargreaves KM. Pain mechanisms of the pulpodentin complex. In: Hargreaves KM, Goodis HE, editors. Seltzer and Bender's Dental Pulp. 3rd Revised Edition. Hannover Park: Quintessence Publishing Co. Inc.; 2002. pp. 181–203. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scherman A, Jacobsen PL. Managing dentin hypersensitivity: What treatment to recommend to patients. J Am Dent Assoc. 1992;123:57–61. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1992.0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ide M, Wilson RF, Ashley FP. The reproducibility of methods of assessment for cervical dentine hypersensitivity. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:16–22. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.280103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holland GR, Narhi MN, Addy M, Gangarosa L, Orchardson R. Guidelines for the design and conduct of clinical trials on dentine hypersensitivity. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:808–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corona SA, Nascimento TN, Catirse AB, Lizarelli RF, Dinelli W, Palma-Dibb RG. Clinical evaluation of low-level laser therapy and fluoride varnish for treating cervical dentinal hypersensitivity. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30:1183–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2003.01185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar NG, Mehta DS. Short-term assessment of the Nd: YAG laser with and without sodium fluoride varnish in the treatment of dentin hypersensitivity – A clinical and scanning electron microscopy study. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1140–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.7.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lan WH, Liu HC, Lin CP. The combined occluding effect of sodium fluoride varnish and Nd: YAG laser irradiation on human dentinal tubules. J Endod. 1999;25:424–6. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(99)80271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pesevska S, Nakova M, Ivanovski K, Angelov N, Kesic L, Obradovic R, et al. Dentinal hypersensitivity following scaling and root planing: Comparison of low-level laser and topical fluoride treatment. Lasers Med Sci. 2010;25:647–50. doi: 10.1007/s10103-009-0685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu PJ, Chen JH, Chuang FH, Roan RT. The combined occluding effects of fluoride-containing dentin desensitizer and Nd-Yag laser irradiation on human dentinal tubules: An in vitro study. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2006;22:24–9. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70216-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tengrungsun T, Sangkla W. Comparative study in desensitizing efficacy using the GaAlAs laser and dentin bonding agent. J Dent. 2008;36:392–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarbet WJ, Silverman G, Stolman JM, Fratarcangelo PA. An evaluation of two methods for the quantitation of dentinal hypersensitivity. J Am Dent Assoc. 1979;98:914–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1979.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walters PA. Dentinal hypersensitivity: A review. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005;6:107–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillam DG, Bulman JS, Newman HN. A pilot assessment of alternative methods of quantifying dental pain with particular reference to dentine hypersensitivity. Community Dent Health. 1997;14:92–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tailor A, Shenoy N, Thomas B. To compare and evaluate the efficacy of bifluorid 12, diode laser and their combined effect in treatment of dentinal hypersensitivity – A clinical study. Nitte Univ J Health Sci. 2014;4:54–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gangarosa LP., Sr Current strategies for dentist-applied treatment in the management of hypersensitive dentine. Arch Oral Biol. 1994;39(Suppl):101S–6S. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(94)90195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura Y, Wilder-Smith P, Yonaga K, Matsumoto K. Treatment of dentine hypersensitivity by lasers: A review. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:715–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027010715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pashley DH. Dentin permeability and dentin sensitivity. Proc Finn Dent Soc. 1992;88(Suppl 1):31–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ling TY, Gillam DG. The effectiveness of desensitizing agents for the treatment of cervical dentine sensitivity (CDS) – A review. J West Soc Periodontol Periodontal Abstr. 1996;44:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu HC, Lan WH. The combined effectiveness of the semiconductor laser with duraphat in the treatment of dentin hypersensitivity. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 1994;12:315–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ritter AV, de L Dias W, Miguez P, Caplan DJ, Swift EJ., Jr Treating cervical dentin hypersensitivity with fluoride varnish: A randomized clinical study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1013–20. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumoto K, Funai H, Wakabayashi H. Study on the treatment of hypersensitive dentine by GaAIAs laser diode. J Conserv Dent. 1985;28:766–71. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamaguchi M, Ito M, Miwata T, Horiba N, Matsumoto T, Nakamura H, et al. Clinical study on the treatment of hypersensitive dentin by GaAlAs laser diode using the double blind test. Aichi Gakuin J Dent Sci. 1990;28:703–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumazaki M, Zennyu K, Inoue M, Fujii B. Clinical evaluation of GaAlAs-semiconductor laser in the treatment of hypersensitive dentin. J Conserv Dent. 1990;33:911–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y, Gao J, Gao Y, Xu S, Zhan X, Wu B. In vitro study of dentin hypersensitivity treated by 980-nm diode laser. J Lasers Med Sci. 2013;4:111–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lan WH, Lee BS, Liu HC, Lin CP. Morphologic study of Nd: YAG laser usage in treatment of dentinal hypersensitivity. J Endod. 2004;30:131–4. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200403000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Umberto R, Claudia R, Gaspare P, Gianluca T, Alessandro del V. Treatment of dentine hypersensitivity by diode laser: A clinical study. Int J Dent 2012. 2012:858950. doi: 10.1155/2012/858950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]