Abstract

Background:

Prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MeS) is high among Asians, including Indians and is rising, particularly with the adoption of modernized lifestyle. Various studies have reported a significant relationship between periodontal status and MeS. The objective of this study is to investigate the association between periodontitis and MeS.

Materials and Methods:

The study included 259 subjects (130 cases with chronic periodontitis, 129 controls without chronic periodontitis) who underwent medical and periodontal checkup. Five components (obesity, high blood pressure, low- and high-density lipoproteins, cholesterol, hypertriglyceridemia, and high plasma glucose) of MeS were evaluated, and individuals with ≥3 positive components were defined as having MeS. The periodontal parameter was clinical attachment level (CAL) on the basis of which cases were selected with moderate (CAL loss 3–4 mm) and severe (CAL loss ≥5 mm) generalized chronic periodontitis. The association between chronic periodontitis and MeS components was investigated using odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results:

The association of MeS and chronic periodontitis was strong and significant with OR: 2.64, 95% CI: 1.36–5.18, and P < 0.003. Comparison of mean values of components of MeS between cases and controls reveals that the mean waist circumference (mean difference: −4.8 [95% CI: 7.75–−1.84], P < 0.002) and mean triglycerides level (mean difference: −25.75 [95% CI: −49.22–−2.28], P < 0.032) were significantly higher in cases than in control groups. Although mean systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and fasting blood sugar level were higher in cases (125.77, 82.99 and 86.38, respectively) compared with control (122.81, 81.3 and 83.68, respectively), it was statistically insignificant.

Conclusion:

The results of this study suggest that there is a strong association between chronic periodontitis and MeS. The association was independent of the various potential confounding risk factors affecting the chronic periodontitis such as age, sex, residential background, and tobacco consumption.

Key words: Chronic periodontitis, hypertriglyceridemia, metabolic syndrome, obesity, plasma glucose

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is a chronic infectious disease of the supporting tissues of the teeth, with multiple related factors.[1] In recent years, interest has grown regarding the relationship with other systemic conditions to identify some new aspects to improve diagnostic tools and treatment outcomes.[2]

Metabolic syndrome (MeS) consists of a combination of impaired glucose regulation, abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia, and high blood pressure.[3] It is estimated that approximately one-fourth of the world's adult population is affected by MeS.[4] It is generally accepted that the origin is a pro-inflammatory state derived from excessive calorie intake and over nutrition and other chronic inflammatory diseases. Oxidative stress has been proposed as a potential common link to explain relationship among each component of MeS and periodontitis.[5]

A cross-sectional study conducted by Shimazaki et al., in 2007, showed that individuals exhibiting more components of MeS had a higher odds ratio (OR) for a greater periodontal probing depth (PD) and clinical attachment level (CAL).[6] In addition, other cross-sectional studies revealed that individuals with MeS had a higher risk for poor periodontal status,[7,8,9,10,11,12] and those individuals with poor periodontal status had a higher risk for MeS.[13,14,15,16]

Elevated blood levels of inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin (IL)-6, were reported in patients with periodontal disease,[17,18] suggesting that periodontal disease is a mild chronic inflammatory disease affecting the systemic conditions.[19,20] Aggravation of glucose tolerance in people with deep periodontal pockets was also shown epidemiologically, suggesting that infection with periodontal disease pathogens enhance tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) production, induces the prediabetic condition, and leads to abnormal glucose tolerance.[21]

Furthermore, negative influences by lipopolysaccharide and cytokines produced by inflammation, such as TNF-α and IL-1 on lipid metabolism, were reported,[22] suggesting that Gram-negative anaerobe-induced periodontal disease has some influence on lipid metabolism. Considering these findings, it is possible that periodontal disease increases the risk of developing MeS as a Gram-negative anaerobe-induced mild chronic inflammatory disease.[23] Prevalence of MeS is high among Asians including Indians and is rising, particularly with the adoption of modernized lifestyle.[23] However, little information is available on the possible association between periodontitis and MeS as a sole clinical entity in Indian population; this study was carried out to assess the association between MeS and chronic periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The total percentage of rural population in Himachal Pradesh 90.20% of the total population residing in 17,495 inhabited villages. The rural population has limited access to health-care facility as compared to the urban population. Himachal Pradesh has the highest percentage of rural population among all the states of the country with poor socioeconomic status as compared to those residing in urban areas. Per capita income at current prices is Rs. 82,611 as per the recent survey conducted by the Department of Economics and Statistics.

Patients and study design

The study approved by the Ethics Committee of the H.P. Government Dental College, Shimla, India, had a cross-sectional design. The cases and controls were screened on the basis of CAL according to the American Academy of Periodontology classification system. Subjects meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria were invited to take part in the study and were provided with the subject information sheet and consent form. Three hundred and seventy-eight subjects were enrolled for the study of duration 22 months. Among all the consecutive patients population referred for care to the outpatient Department of Periodontology and services of H.P. Government Dental College and Hospital, Shimla, India, 119 (out of 378 subjects) patients did not complete the study. The sample used was a convenient sample. Therefore, among the 259 subjects who completed the study, 130 individuals diagnosed with moderate/severe periodontitis were enrolled in the periodontal clinic, whereas 129 patients without periodontitis were invited to participate while attending the oral surgery or restorative clinics and served as nonaffected controls. All subjects gave a written informed consent. Thus, patients with moderate/severe chronic periodontitis formed the study population and those without periodontitis on clinical evaluation formed the control group.

The cases were screened from individuals who presented with clinical signs of periodontal disease. Periodontal disease was assessed by a comprehensive examination. However, screening of cases, i.e., individuals with moderate/severe periodontitis, was based on mean clinical attachment loss measured at four sites per tooth (mesiobuccal, buccal, distobuccal, and lingual) of the entire dentition except for third molars. Inclusion criteria for the cases were diagnosis of moderate/severe periodontitis based on the 1999 Consensus Classification of Periodontal Disease by Armitage and Thomas F. Flemmig (1999).[24]

Inclusion criteria for cases with moderate/severe chronic periodontitis: (1) Patients with at least 20 teeth and more than 30% of sites exhibiting 3–4 mm of mean clinical attachment loss for moderate chronic periodontitis and more than 30% of sites ≥5 mm of mean clinical attachment loss for severe chronic periodontitis, (2) Minimum age of 20 years, and (3) Patients consenting to participate. Inclusion criteria for controls: (1) The absence of the clinical and radiographic manifestations of periodontal disease, (2) At least, 20 teeth present in the oral cavity and no history of periodontal treatment in the past, (3) Minimum age of 20 years, and (4) Patients consenting to participate.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients not willing to participate in the study, (2) pregnant patients, (3) patients of rheumatic heart disease, congenital heart disease and/or with prosthetic valves who were at high risk for endocarditis, and (4) all patients medically unfit to participate in the study. Nearly 50.19% cases and 49.80% controls participated in the study.

MeS was diagnosed based on the presence of three of the five following components using modified Adult Treatment Panel III criteria:[25] (1) Abdominal/central obesity (as indicated by increased waist circumference or markedly increased body mass index [BMI] and defined as waist circumference with ethnicity-specific values): Waist circumference ≥90 cm in men and ≥80 cm in women (based on a Chinese, Malay, and Asian–Indian population), (2) Hypertriglyceridemia: ≥150 mg/dL (1.69 mmol/L), (3) Low- and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol: <40 mg/dL (1.04 mmol/L) in men; <50 mg/dL (1.29 mmol/L) in women, (4) High blood pressure: ≥130/≥85 mmHg, and (5) High fasting glucose: ≥100 mg/dL (6.1 mmol/L).

Statistical analysis

SPSS package version 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used. The value of continuous variables was expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The distribution of discrete variables in patients and control group was expressed as percentages. The significance of difference in mean values of continuous variables between study and control group was estimated by Student's t-test. The significance of the difference in the distribution of discrete variables between the groups was estimated with Chi-square test. Association between chronic periodontitis and MeS was estimated by calculating OR with 95% confidence interval (CI). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

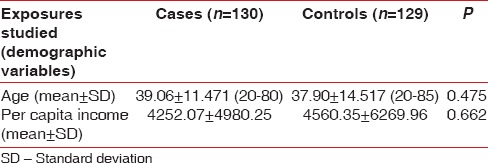

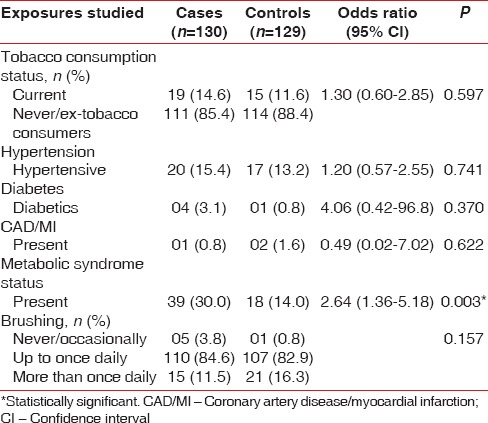

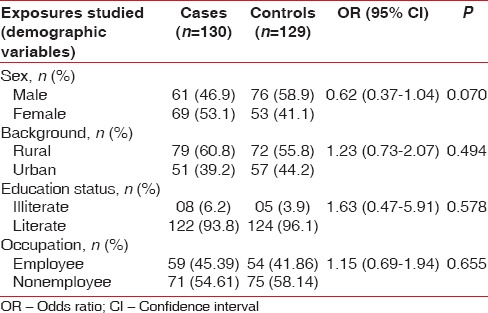

The study is attempted to evaluate the association between MeS and chronic periodontitis in case–control study design. The cases and controls were well matched with insignificant difference for age (mean age: 39.06 vs. 37.9, P < 0.475), sex (male: 46.9% vs. 58.9%, P < 0.070), residential background (rural: 60.8% vs. 55.8%, P < 0.494), educational status (illiterate: 6.2% vs. 3.9%, P < 0.578), occupation (employed: 45.39% vs. 41.86%, P < 0.655), and tobacco consumption status (current tobacco consumers: 14.6% vs. 11.6%, P < 0.597). The prevalence of diabetes (3.1% vs. 0.8%, P < 0.37), hypertension (15.4% vs. 13.2%, P < 0.741), and coronary artery disease/myocardial infarction (0.8% vs. 1.6%, P < 0.622) was also similar in both the two groups [Tables 1–3].

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population

Table 3.

Risk factors and atherovascular disease distribution among the study population

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the study population

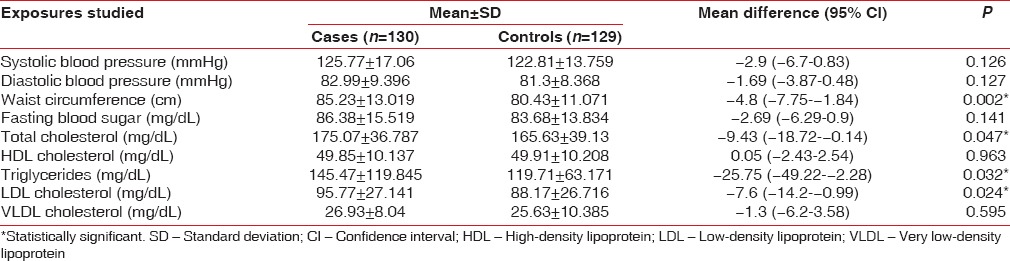

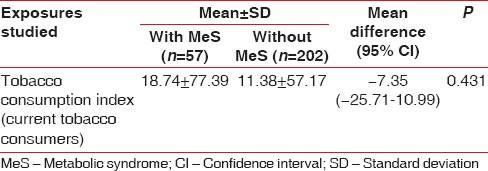

However, the association of MeS and chronic periodontitis was strong and significant with OR: 2.64, 95% CI: 1.36–5.18, and P < 0.003 [Table 3]. Comparison of mean values of components of MeS and lipid parameters between cases and controls reveals that the mean waist circumference (mean difference: −4.8 [95% CI: −7.75–−1.84], P < 0.002), mean total cholesterol level (mean difference: −9.43 [95% CI: −18.72–−0.14], P < 0.047), mean triglycerides level (mean difference: −25.75 [95% CI: −49.22–−2.28], P < 0.032), and mean LDL level (mean difference: −7.6 [−14.2–−0.99], P < 0.024) were significantly higher in cases than in control groups. There was no significant difference in the mean systolic blood pressure (−2.9 [95% CI: −6.7–0.83], P < 0.126), diastolic blood pressure (−1.69 [95% CI: −3.87–0.48], P < 0.127), and HDLs levels (0.05% [95% CI: −2.43–2.54], P < 0.963) in the two groups. Although mean systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and fasting blood sugar level were higher in cases (125.77, 82.99, and 86.38, respectively) compared with control (122.81, 81.3, and 83.68, respectively), it was statistically insignificant [Table 4]. The observed strong association between chronic periodontitis and MeS is unlikely to be influenced by the tobacco consumption pattern in the study and control groups as comparison of the distribution of tobacco consumption index in two groups was statistically insignificant [Table 5].

Table 4.

Frequency and distribution of biological variables among the study population

Table 5.

Frequency and distribution of tobacco consumption index of current tobacco consumers among the subjects with or without metabolic syndrome

DISCUSSION

The results of this study suggest that there is a strong association of MeS and chronic periodontitis was strong and significant with OR: 2.64, 95% CI: 1.36–5.18, and P < 0.003. The association was independent of the various potential confounding risk factors affecting the chronic periodontitis such as age, gender, residential background, and tobacco consumption.

Chronic periodontitis has been associated with systemic alteration such as low-grade inflammation, dyslipidemia, a procoagulant state, glucose intolerance, and endothelial dysfunction.[13] It leads to the state of the chronic systemic inflammatory state through the release of various inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1, TNF-α, and CRP, which may worsen the insulin resistance.[26,27] Further, the production of oxidative stress-enhancing reactive oxygen species in affected periodontal tissues is a potential factor which could increase insulin resistance [5] that may result in MeS. MeS is characterized by state of constellation of metabolic and biological risk factors presumed to be the result of insulin resistance which is thought to be the outcome of the complex interaction of acquired environmental factors related to lifestyle and genetic predisposition.[28,29]

MeS is an independent risk factor for diabetes and atherosclerotic vascular disease.[13,28,29,30] The studies also suggested the association between MeS and chronic periodontitis but the exact mechanism is not known.[6,8,11,13,26,27,31] MeS could also be a predisposing factor for chronic periodontitis [6] and it can influence the periodontal disease process.[13] MeS is known to affect normal vascular function and it may increase the vulnerability for infection because of its predisposition to glucodysregulation.[28] Individual risk factors of MeS such as obesity can affect the levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1,[32] alterations in T-cells and monocytes for macrophage and increased cytokine production, abnormally elevated cytokines IL-6 and -1 and TNF-α,[27] all of which contribute to periodontitis. Adipose tissue can produce cytokines and prostaglandins,[33] which play an important role in tissue destruction during periodontal disease.[34] Lipids and glucose can also deeply affect the immune system. In obese, hypertensive rats, hyperplasia and hypertrophy of the walls of blood vessels supplying the periodontium was observed.[35] Thus, all the individual risk factors for MeS either affect the normal periodontium or the periodontal disease process. Conversely, as an infectious process with a prominent inflammatory component, periodontal disease can adversely affect MeS.[26,27] Thus, associations between chronic periodontitis and MeS could be bidirectional.

Thus, observations in present case–control study strongly suggest the significant association between chronic periodontitis and MeS. The underlying cause-and-effect relationship needs to be explored in future interventional studies that would have important implications in management and preventive strategies of both these conditions more effectively. The association between chronic periodontitis and MeS has also been observed by various studies.[6,8,9,10,11,13,26,27,31] The finding from this study is in agreement with the findings by Shimazaki et al.,[6] which reported that MeS among 584 Japanese women was associated with an increased risk for periodontitis. Analysis of data from 13,710 participants in the NHANES III by D'Aiuto et al.[13] showed a direct relationship between periodontitis and the prevalence of MeS. Khader et al.[26] showed that the severity of periodontal disease, as measured by average PD and average CAL, and the extent of periodontal disease, as measured by the percentage of sites with CAL ≥3 mm and the percentage of sites with PD ≥3 mm, were significantly greater among patients with MeS compared to those without MeS.

Thus, the link between MeS and periodontitis could be bidirectional. Oxidative stress lies at the heart of the two-way association. It is generally accepted that the origin of metabolic disorders is in “pro-inflammatory” state derived from excessive caloric intake, over nutrition, and other chronic inflammatory conditions.[36,37] The pro-inflammatory status also leads to an increase in oxidative stress, which has potential to impair several crucial biological mechanisms.[38,39] A study has demonstrated an increase in the products of oxidative damage in peripheral blood from persons with periodontitis, which emphasized the influence of periodontitis on serum and/or plasma oxidative markers.[40] Reduced antioxidant capacity was also found in persons with periodontitis.[41] Pro/anti-oxidant capacity between periodontitis and MeS could add the evidence for elucidating the mechanism of the link between periodontitis and MeS. By removing all confounding potential risk factors for periodontitis and MeS, the strong association between the two diseases in our study was not by chance, thus disproving the null hypothesis which was also substantiated by the other previous studies.[6,8,11,13,26,27,31]

Limitations and suggestions

The design of the study is such that the causal relationship between periodontal diseases and MeS cannot be identified. Attrition of 119 subjects from the study can lead to important loss of the information of the study. Multiple logistic regression and multivariate analysis were not done which would have helped in finding out the correlation of the different variables in the study. Other confounding variables, for example, in between snacking, lack of exercise, genetics, and hereditary were not included in the study. As the study is conducted in the individuals with more than “20” teeth, the relation between periodontal disease and MeS with <“20” teeth and among edentulous remains unknown. In future, a study should be carried out taking into considerations the above-mentioned facts.

CONCLUSION

This study concludes a strong association between chronic periodontitis and MeS. The association was independent of the various potential confounding risk factors affecting the chronic periodontitis such as age, gender, residential background, and tobacco consumption. Keeping in mind this association, dental professionals in general and periodontists in particular should take MeS into consideration when evaluating periodontitis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank all the patients who agreed to take part in the study, the administration of the dental college for granting permission to conduct the study, and the statistician for the statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 2005;366:1809–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67728-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watt RG, Petersen PE. Periodontal health through public health – The case for oral health promotion. Periodontol 2000. 2012;60:147–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365:1415–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cameron AJ, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome: Prevalence in worldwide populations. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2004;33:351–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bullon P, Morillo JM, Ramirez-Tortosa MC, Quiles JL, Newman HN, Battino M. Metabolic syndrome and periodontitis: Is oxidative stress a common link? J Dent Res. 2009;88:503–18. doi: 10.1177/0022034509337479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimazaki Y, Saito T, Yonemoto K, Kiyohara Y, Iida M, Yamashita Y. Relationship of metabolic syndrome to periodontal disease in Japanese women: The Hisayama study. J Dent Res. 2007;86:271–5. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kushiyama M, Shimazaki Y, Yamashita Y. Relationship between metabolic syndrome and periodontal disease in Japanese adults. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1610–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morita T, Ogawa Y, Takada K, Nishinoue N, Sasaki Y, Motohashi M, et al. Association between periodontal disease and metabolic syndrome. J Public Health Dent. 2009;69:248–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2009.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benguigui C, Bongard V, Ruidavets JB, Chamontin B, Sixou M, Ferrières J, et al. Metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and periodontitis: A cross-sectional study in a middle-aged French population. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:601–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han DH, Lim SY, Sun BC, Paek D, Kim HD. The association of metabolic syndrome with periodontal disease is confounded by age and smoking in a Korean population: The Shiwha-Banwol environmental health study. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:609–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andriankaja OM, Sreenivasa S, Dunford R, DeNardin E. Association between metabolic syndrome and periodontal disease. Aust Dent J. 2010;55:252–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Timonen P, Niskanen M, Suominen-Taipale L, Jula A, Knuuttila M, Ylöstalo P. Metabolic syndrome, periodontal infection, and dental caries. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1068–73. doi: 10.1177/0022034510376542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Aiuto F, Sabbah W, Netuveli G, Donos N, Hingorani AD, Deanfield J, et al. Association of the metabolic syndrome with severe periodontitis in a large U.S. population-based survey. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3989–94. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nesbitt MJ, Reynolds MA, Shiau H, Choe K, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L. Association of periodontitis and metabolic syndrome in the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2010;22:238–42. doi: 10.1007/bf03324802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bensley L, VanEenwyk J, Ossiander EM. Associations of self-reported periodontal disease with metabolic syndrome and number of self-reported chronic conditions. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon YE, Ha JE, Paik DI, Jin BH, Bae KH. The relationship between periodontitis and metabolic syndrome among a Korean nationally representative sample of adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:781–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saito T, Murakami M, Shimazaki Y, Oobayashi K, Matsumoto S, Koga T. Association between alveolar bone loss and elevated serum C-reactive protein in Japanese men. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1741–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.12.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loos BG, Craandijk J, Hoek FJ, Wertheim-van Dillen PM, van der Velden U. Elevation of systemic markers related to cardiovascular diseases in the peripheral blood of periodontitis patients. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1528–34. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.10.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishimura F, Soga Y, Iwamoto Y, Kudo C, Murayama Y. Periodontal disease as part of the insulin resistance syndrome in diabetic patients. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2005;7:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slade GD, Ghezzi EM, Heiss G, Beck JD, Riche E, Offenbacher S. Relationship between periodontal disease and C-reactive protein among adults in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1172–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.10.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saito T, Shimazaki Y, Kiyohara Y, Kato I, Kubo M, Iida M, et al. The severity of periodontal disease is associated with the development of glucose intolerance in non-diabetics: The Hisayama study. J Dent Res. 2004;83:485–90. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardardóttir I, Grünfeld C, Feingold KR. Effects of endotoxin and cytokines on lipid metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1994;5:207–15. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199405030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamble P, Deshmukh PR, Garg N. Metabolic syndrome in adult population of rural Wardha, central India. Indian J Med Res. 2010;132:701–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khader Y, Khassawneh B, Obeidat B, Hammad M, El-Salem K, Bawadi H, et al. Periodontal status of patients with metabolic syndrome compared to those without metabolic syndrome. J Periodontol. 2008;79:2048–53. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li P, He L, Sha YQ, Luan QX. Relationship of metabolic syndrome to chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2009;80:541–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung. Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Jr, Cleeman JI, Smith SC, Jr, Lenfant C, et al. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109:433–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levesque J, Lamarche B. The metabolic syndrome: Definitions, prevalence and management. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics. 2008;1:100–8. doi: 10.1159/000112457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moebus S, Hanisch JU, Aidelsburger P, Bramlage P, Wasem J, Jöckel KH. Impact of 4 different definitions used for the assessment of the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in primary healthcare: The German metabolic and cardiovascular risk project (GEMCAS) Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2007;6:22. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morita T, Yamazaki Y, Mita A, Takada K, Seto M, Nishinoue N, et al. A cohort study on the association between periodontal disease and the development of metabolic syndrome. J Periodontol. 2010;81:512–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.090594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimomura I, Funahashi T, Takahashi M, Maeda K, Kotani K, Nakamura T, et al. Enhanced expression of PAI-1 in visceral fat: Possible contributor to vascular disease in obesity. Nat Med. 1996;2:800–3. doi: 10.1038/nm0796-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: Advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294:1871–5. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gemmell E, Marshall RI, Seymour GJ. Cytokines and prostaglandins in immune homeostasis and tissue destruction in periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 1997;14:112–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perlstein MI, Bissada NF. Influence of obesity and hypertension on the severity of periodontitis in rats. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977;43:707–19. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(77)90055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghanim H, Aljada A, Hofmeyer D, Syed T, Mohanty P, Dandona P. Circulating mononuclear cells in the obese are in a proinflammatory state. Circulation. 2004;110:1564–71. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000142055.53122.FA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tripathy D, Mohanty P, Dhindsa S, Syed T, Ghanim H, Aljada A, et al. Elevation of free fatty acids induces inflammation and impairs vascular reactivity in healthy subjects. Diabetes. 2003;52:2882–7. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.12.2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hansel B, Giral P, Nobecourt E, Chantepie S, Bruckert E, Chapman MJ, et al. Metabolic syndrome is associated with elevated oxidative stress and dysfunctional dense high-density lipoprotein particles displaying impaired antioxidative activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4963–71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montebugnoli L, Servidio D, Miaton RA, Prati C, Tricoci P, Melloni C. Poor oral health is associated with coronary heart disease and elevated systemic inflammatory and haemostatic factors. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:25–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6979.2004.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akalin FA, Baltacioglu E, Alver A, Karabulut E. Total antioxidant capacity and superoxide dismutase activity levels in serum and gingival crevicular fluid in pregnant women with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2009;80:457–67. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]