Abstract

Desquamative gingivitis (DG) is a clinical condition in which the gingiva appears reddish, glazed, and friable with loss of superficial epithelium. DG is considered a clinical manifestation of many gingival diseases and hence not identified as a diagnosis itself. Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) is an autoimmune vesiculobullous disorder of mucous membrane characterized by subepithelial bullae formation. MMP can affect the mucous membranes of oral cavity, conjunctiva, nasopharynx, larynx, esophagus, genitourinary tract, and anus and vary in its severity. The most commonly affected sites are oral cavity and conjunctiva. Since DG may be the early sign or only presenting sign of these conditions, most of the times, dental surgeon plays a key role in the diagnosis and prevention of the systemic complications of these diseases. We report a case of a 41-year-old male patient presented with DG. Histopathological examination revealed subepithelial clefting suggestive of MMP. The patient was treated with topical application of triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% 3–4 times a day for 1 month.

Key words: Benign mucous membrane pemphigoid, corticosteroids, desquamative gingivitis, perilesional biopsy

INTRODUCTION

Desquamative gingivitis (DG) is considered as the gingival manifestation of mucocutaneous disorders including pemphigus vulgaris, mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP), bullous pemphigoid, lichen planus, lichenoid mucositis, paraneoplastic pemphigus, linear immunoglobulin A (IgA) disease, psoriasis, and allergic reaction to certain chemicals.[1,2] Hence, it cannot be considered a definitive diagnosis, mandating the identification of the cause of DG. MMP, pemphigus vulgaris, and bullous lichen planus are considered as main cause of DG. Clinically, the desquamation may be mild insignificant patches or widespread erythema with glazed appearance.[2] Most of the time, patients report with burning sensation while taking hot or spicy food items. An accurate diagnosis of the underlying diseases can be made by taking a thorough history, clinical examination, and histopathological examination.

MMP is an uncommon chronic autoimmune vesiculobullous disorder of mucous membrane characterized by junctional separation at the basement membrane resulting in subepithelial slit formation.[2] MMP can affect the mucous membranes of oral cavity, conjunctiva, nasopharynx, larynx, esophagus, genitourinary tract, and anus. The most commonly affected sites are oral cavity and conjunctiva.[3] Skin also can be affected in some cases. MMP is primarily caused due to autoantibodies directed against proteins in the basement membrane zone. In most of the cases, IgG and complement C3 will get deposited at the basement membrane zone.[4]

This article presents a case of DG as the only presenting sign of MMP. It gives an insight into the clinical features, diagnosis, and management of such cases.

CASE REPORT

A 41-year-old male patient reported to the Department of Periodontics, MGPGI, with a chief complaint of bleeding gums and burning sensation on gums while taking hot and spicy food for the past 2 months. The patient did not give any relevant medical and dental history. He was moderately built and nourished.

Intraoral examination revealed mild calculus deposits with generalized gingival inflammation. The marginal, attached, and papillary gingiva appeared to be erythematous and desquamated in relation to upper anterior and lower canines and premolars in the labial aspect and relation to lower molars in the lingual aspect [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Labial aspect of right upper and lower teeth showing desquamation

Figure 2.

Labial aspect of left upper and lower teeth showing desquamation

Gentle manipulation of gingiva induced bulla formation in the marginal and papillary gingiva in relation to 21, 22 [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Bulla formation in relation to marginal gingival and interdental papilla of 21 and 22

Positive Nikolsky sign was present [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Desquamation evident in relation to 21 and 22

Patient's oral hygiene was fair with mild calculus deposits and positive bleeding on probing without any other periodontal problems. White patches of epithelium were visible in some areas of desquamation.

Considering the history and clinical findings, a provisional diagnosis of DG due to vesiculobullous disease and a differential diagnosis of MMP, pemphigus vulgaris, bullous pemphigoid, and bullous lichen planus were given. Incisional biopsy was taken from perilesional area for histopathological examination.

Histopathological examination

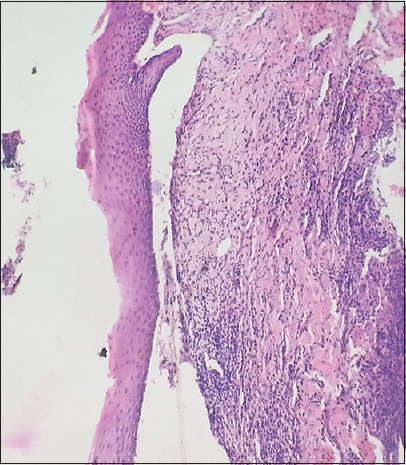

The histopathological examination revealed parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium with subepithelial cleft [Figure 5]. The connective tissue stroma revealed mild chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate.

Figure 5.

Histopathological picture showing subepithelial clefting

The histopathological picture was suggestive of MMP.

The final diagnosis of MMP is made based on the history, clinical presentation, and histopathological examination. Dermatologic and ophthalmic consultations have been done to rule out skin and conjunctival involvement.

After thorough oral prophylaxis, the patient was prescribed topical application of triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% 3–4 times a day for 1 month. A custom made soft tray was used to increase the contact of gel with the tissues [Figure 6]. Periodic check-up was done once in 2 weeks. The lesion has reduced considerably after 6 weeks of application [Figure 7].

Figure 6.

Custom made tray for application of topical steroids

Figure 7.

(a-c) Two months postoperative photograph showing complete resolution of desquamation

DISCUSSION

DG is a common clinical appearance of a variety of mucocutaneous diseases. It was first described by Tomes and Tomes in 1894 and its clinical features including erythema, desquamation, erosion, and blistering of gingival has been described by Prinz in 1932.[5] Literature suggests that 75% of DG cases have a dermatological cause. Nisengard had described the criteria for the diagnosis of DG. These are (1) presence of nonplaque-induced gingival erythema, (2) gingival desquamation, (3) other intraoral or sometimes extraoral lesions, and (4) sore mouth while taking spicy foods.[1] Appropriate diagnosis of underlying disease is very important in the treatment of DG.

MMP is a chronic autoimmune subepithelial disease that primarily affects mucous membranes of the body. It is also called as benign MMP, cicatricial pemphigoid (“cicatrix” means scar), oral pemphigoid. The scarring caused by MMP can even result in blindness.[4,6] Hence, this cannot be considered as benign and the term “benign MMP” is not in use now. The mucosal lesions in the gingiva generally do not scar, but scarring is a critical and common finding in ocular and other mucosal lesions. This may result further complications such as blindness, laryngeal or pharyngeal stenosis, and even death. In severe cases, adhesions may develop between buccal mucosa and alveolar mucosa and floor of the mouth and tongue resulting in ankyloglossia.[5]

The probable pathogenesis of MMP includes an autoantibody-induced complement-mediated sequestration of leukocytes with resultant release of cytokines and leukocytes causing detachment of basal cells from basement membrane zone. This results in subepithelial slit formation which is the classic histopathological finding in MMP. BP180 epidermal antigen is the major target of IgG autoantibodies produced by MMP patients.[2] Studies have shown that the antigens associated with MMP are more frequently seen in the lamina lucida portion of basement membrane.

The oral cavity usually represents the first site or the only site of disease involvement. The oral cavity presentation is seen in almost all cases and the initial presentation is oral in 48% and ocular in 30%. In oral cavity, gingival involvement is seen in 100% of cases.[7] The disease usually appears in the fourth and fifth decade of life as in our case. However, it has also been reported even in children and young adults.[8] It is more common in females with a female to male ratio of 2:1; however, in our case, it presented in a male patient. Common intraoral findings include DG, erosions, and ulceration with burning sensation while taking spicy foods and positive Nikolsky sign which is in accordance with our case. Other intraoral sites such as buccal mucosa, tongue, palate, and floor of the mouth may also be involved.

Conjunctiva is the second most involved site with an occurrence rate of 3–48%. Progressive scarring and corneal damage may lead to blindness in 15% of cases.[5]

The diagnosis is generally made by histopathology and direct immunofluorescence. Histopathology reveals subepithelial slit formation which was present in our case. Direct immunofluorescence usually reveals linear deposition of IgG and C3 in the basement membrane zone.

A multidisciplinary approach is necessary for the management of MMP for reducing the disease-related complications. The first international consensus on MMP recommended dividing patients into “low-risk” and “high-risk” category based on the sites involved; “low-risk” patients defined as having only oral mucosal and skin involvement and “high-risk” patients defined as having ocular, genital, nasopharyngeal, esophageal, laryngeal mucosa involvement.[3] Mild cases can be treated by using topical corticosteroids, intralesional corticosteroid injections. In high-risk patients, systemic corticosteroids, other immunosuppressants such as methotrexate or intravenous Igs may be given. Recently low-level laser therapy also has been used to improve the healing of tissue after local corticosteroid application.[5]

In the present case, based on the patient history, clinical presentation, and histopathological report, a diagnosis of MMP with exclusive gingival involvement was established and has been treated with oral prophylaxis and topical steroid application for 2 months. The lesions have subsided considerably and the patient has been put on periodic recall protocol.

CONCLUSION

DG as the only presenting sign of MMP is quite rare occurrence. Proper diagnosis and treatment at the earliest are necessary to prevent the progression of disease and disease-related complications. Since oral cavity is most commonly affected site, dentists play a vital role in identifying the disease at an early stage. Thorough knowledge about DG and associated conditions is necessary for the same.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nisengard RJ, Rogers RS., 3rd The treatment of desquamative gingival lesions. J Periodontol. 1987;58:167–72. doi: 10.1902/jop.1987.58.3.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scully C, Laskaris G. Mucocutaneous disorders. Periodontol 2000. 1998;18:81–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1998.tb00140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neff AG, Turner M, Mutasim DF. Treatment strategies in mucous membrane pemphigoid. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:617–26. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darling MR, Daley T. Blistering mucocutaneous diseases of the oral mucosa – A review: Part 1.Mucous membrane pemphigoid. J Can Dent Assoc. 2005;71:851–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasan S, Kapoor B, Siddiqui A, Srivastava H, Fatima S, Akhtar Y. Mucous membrane pemphigoid with exclusive gingival involvement: Report of a case and review of literature. J Orofac Sci. 2012;4:64–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lugovic L, Buljan M, Situm M, Poduje S, Bulat V, Vucic M, et al. Unrecognized cicatricial pemphigoid with oral manifestations and ocular complications. A case report. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2007;15:236–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatia P, Dudhia B, Patel PS, Patel M. Benign mucous membrane pemhigoid. J Ahmedabad Dent Coll Hosp. 2011;2:48–54. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasan S. Desquamative gingivitis – A clinical sign in mucous membrane pemphigoid: Report of a case and review of literature. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2014;6:122–6. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.129177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]