Abstract

Gastric type adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix (GAS) is a rare variant of mucinous endocervical adenocarcinoma not etiologically associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, with minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (MDA) at the well-differentiated end of the morphologic spectrum. These tumors are reported to have worse prognosis than usual HPV-associated endocervical adenocarcinoma (UEA). A retrospective review of GAS was performed from the pathology databases of three institutions spanning 20 years. Stage, metastatic patterns, and overall survival were documented. Forty GAS cases were identified, with clinical follow-up data available for 38. The tumors were subclassified as MDA (n=13) and non-MDA GAS (n=27). Two patients were syndromic (one Li-Fraumeni, one Peutz-Jeghers). At presentation, 59% were advanced stage (FIGO II–IV), 50% had lymph node metastases, 35% had ovarian involvement, 20% had abdominal disease, 39% had at least one site of metastasis at the time of initial surgery, and 12% of patients experienced distant recurrence. The metastatic sites included lymph nodes, adnexa, omentum, bowel, peritoneum, diaphragm, abdominal wall, bladder, vagina, appendix, and brain. Follow-up ranged from 1.4 to 136.0 months (mean, 33.9 months); 20/38 (52.6%) had no evidence of disease, 3/38 (7.9%) were alive with disease, and 15/38 (39.5%) died of disease. Disease specific survival at 5 years was 42% for GAS vs. 91% for UEA. There were no survival differences between MDA and non-MDA GAS. GAS represents a distinct, biologically aggressive type of endocervical adenocarcinoma. The majority of patients present at advanced stage and pelvic, abdominal, and distant metastases are not uncommon.

Keywords: cervix, carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, HPV, gastric, lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia, minimal deviation, clinical outcomes, metastasis

Introduction

Endocervical adenocarcinoma (ECA) represents approximately 20–25% of cervical cancers, with increasing incidence in recent years.1–5 The 2014 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs includes gastric type adenocarcinomas as a variant of mucinous endocervical adenocarcinomas (Table 1).6 By far the most common type of adenocarcinoma is the usual type (UEA); this is associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, most commonly HPV types 16 and 18. However, unlike cervical squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) where nearly all cases are etiologically associated with HPV infection, approximately 10% of ECAs in Western countries are unrelated to HPV.7,8 Therefore, ECA can be subclassified into HPV-associated and HPV-unassociated groups (Table 2). The HPV-associated ECAs can have a variety of morphological appearances, including mucinous features, with or without intestinal differentiation, and they may resemble endometrioid and serous carcinomas. The HPV-unassociated group includes clear cell, mesonephric, and gastric type, including minimal deviation adenocarcinomas (MDA), also known as adenoma malignum.9–11

Table 1.

WHO 2014 classification of glandular tumours of the uterine cervix.

| Glandular tumours and precursors |

|---|

| Endocervical adenocarcinoma, usual type

|

| Mucinous carcinoma, NOS |

| Gastric type |

| Intestinal type |

| Signet-ring cell type

|

| Villoglandular carcinoma

|

| Endometrioid carcinoma

|

| Clear cell carcinoma

|

| Serous carcinoma

|

| Mesonephric carcinoma

|

| Adenocarcinoma admixed with neuroendocrine carcinoma |

Table 2.

Classification of endocervical adenocarcinoma based on association with HPV infection and histologic features.

|

HPV associated

|

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma |

| Endocervical |

| Intestinal |

| Signet-ring |

| Villoglandular

|

|

HPV unassociated

|

| Clear cell carcinoma

|

| Mesonephric carcinoma

|

| Gastric type (GAS) |

| Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (MDA)

|

|

HPV association controversial

|

| Endometrioid

|

| Serous |

MDA are characterized by deceptively low histologic grade, often with neoplastic glands almost indistinguishable from benign endocervical glands.12–16 They exhibit abundant apical mucin, basally oriented nuclei, and, characteristically, little or only very subtle cervical stromal reaction to invasion, making it difficult to diagnose in cervico-vaginal cytology preparations, biopsies, conization specimens, and even hysterectomies. Sometimes deep cervical stromal involvement may be the only overt feature supporting a malignant diagnosis. Clinical outcomes in MDA have been a matter of considerable debate with several studies indicating its aggressive biologic nature, especially compared to UEA,12,14,16 whereas other reports have stated that the difference may not be independent of stage.17 Additionally, MDA has been linked to Peutz-Jeghers syndrome in up to 10% of cases.18–20

Several recent studies have described a new category of mucinous endocervical adenocarcinoma, gastric type adenocarcinoma (GAS), which has a distinctive histological appearance and immunohistochemical (IHC) profile as well as poor clinical outcomes.9,16,20 Histologic criteria for GAS were first defined by Kojima et al. to include cells showing clear and/or pale eosinophilic and voluminous cytoplasm with distinct cell borders comprising the majority of the tumor.16 In some cases benign endocervical glands showing ‘gastric metaplasia’ resembling normal pyloric glands of the antral stomach are found adjacent to invasive adenocarcinoma, and these tumors frequently contain areas that are indistinguishable from MDA. There is histochemical, immunohistochemical, and etiologic overlap as well: both lesions feature acidic mucin and an immunohistochemical profile similar to normal gastric mucus cells, with expression of HIK1083, lysozyme, and pepsinogen II.13,16 They are negative for HPV DNA (by PCR) and p16 (by immunohistochemistry), with only rare exceptions.

The term ‘lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia’ (LEGH) was first coined by Nucci et al. to describe a benign pseudoneoplastic endocervical process resembling MDA.21 Almost simultaneously, Mikami et al. described a series of similar lesions using the terminology “pyloric gland metaplasia.”22 Subsequently, LEGH was shown to have features of gastric metaplasia and, similar to GAS, had a gastric-type IHC profile,23–27 prompting some authors to consider LEGH to be a putative precursor lesion to MDA and GAS.23,26,28,29

Kojima’s landmark study looked at only 16 cases of GAS (including MDA).16 Here, we characterize the clinical outcomes of patients with GAS (including MDA), focusing not only on overall survival, but also on other clinical variables such as sites of metastasis and recurrence.

Materials and Methods

Patients diagnosed with GAS at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) from January 1, 1997 to January 1, 2012 were identified. Additional cases (spanning the period between January 1, 1998 and January 1, 2009) were also included from two collaborating institutions (Jikei University, Tokyo, Japan; Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA).

Hematoxylin and eosin stained histologic sections were reviewed by two pathologists (YSK and KJP) and the diagnoses were established using criteria described by Kojima et al.16 Specifically, tumors showed voluminous clear and/or pale eosinophilic cytoplasm with distinct cell borders in a significant portion of the tumor. None of the tumors showed the typical features of usual type endocervical adenocarcinoma (columnar nuclei with abundant apoptotic bodies and luminal mitotic figures). The results of p16 immunohistochemistry performed for diagnostic purposes in any case were also recorded. All relevant pathologic and clinical data were collected and analyzed. Recurrent histologic findings, including association with LEGH, were recorded and analyzed. The findings were compared to a cohort of 158 usual HPV-associated endocervical adenocarcinomas identified at MSK between January 1, 2002 and January 1, 2012.

While we consider MDA to be a part of the morphologic spectrum of GAS, we collected separate data for these tumors for the purposes of this study to determine whether there were associations between histologic differentiation and clinical biology. Tumors were classified as MDA when the bulk of tumor in the cervix (≥90%) was cytologically low grade (minimal nuclear atypia, abundant apical mucin) with well formed glands sometimes showing the classically described “claw-like” growth pattern and some stromal desmoplasia. Any cases where the presence of an invasive tumor was equivocal by histologic standards were excluded from our study. Tumors were classified as non-MDA when at least 10% of the tumor in the cervix revealed high grade nuclei, prominent nucleoli, significant architectural complexity (more complex than simple glandular, cystic, or claw-shaped), single cells or clusters, or obvious extensive destructive stromal invasion.

Statistical significance of the differences in proportions of cases within each histologic group having various pathologic or clinical features were made using Fisher’s exact test.30 The survival time of each patient was calculated from the date of diagnosis to date of death with right-censoring at date of last follow-up for the patients who were still alive. The cumulative survival probabilities for each group of patients were estimated by life table methods, commonly referred to as the method of Kaplan and Meier.31 The log-rank test was used to compare two survival curves.32,33 The standard errors associated with the survival probabilities at a given time point were calculated from the life table by a modification of the method of Greenwood.34,35

Results

Forty cases were identified (MSK – 29 cases, Chiba University – 9 cases, and Yale University – 2 cases) for which treatment information was available. Follow-up information was collected for 38 cases, as 2 patients were lost to follow-up. Stage at presentation was recorded in all but one patient. All cases were diagnosed and evaluated based on sampling of the cervix (biopsy, curettage, Loop Electrocautery Excision Procedure [LEEP], hysterectomy, trachelectomy, exenteration) except for one case where the only material available was from a peritoneal biopsy. GAS cases were further subclassified as MDA (n=13) or non-MDA (n=27).

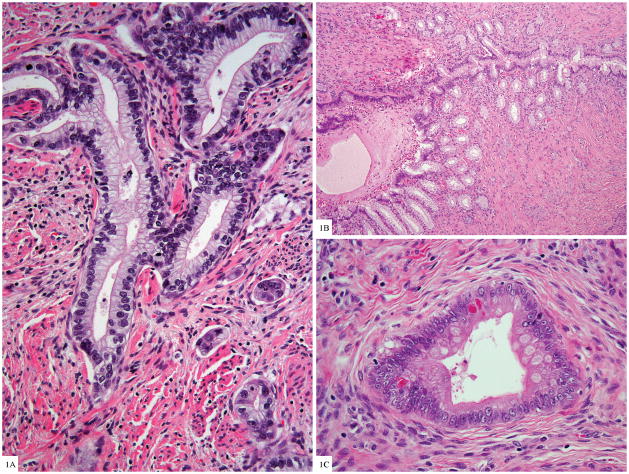

Histologically, the tumors showed the features described by Kojima et al. (Fig. 1A). Additional notable features included presence of LEGH in 20% of the tumors (50% of MDA and 3.8% of non-MDA GAS) (Fig. 1B); cellular dyshesion, single cell infiltration, and signet ring differentiation, especially in the non-MDA tumors and particularly prominent at the advancing edge of the cervical stromal invasion; and focal intestinal differentiation in the form of goblet (26%) or Paneth-like neuroendocrine cells (11%) (Fig. 1C). Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia was usually superficially located in the cervix, often admixed with adjacent invasive carcinoma but not always.

Figure 1.

Figure 1A. Gastric type endocervical adenocarcinoma with voluminous clear cytoplasm and basally located nuclei with moderate cytologic atypia, adjacent small invasive tumor clusters (H&E 100×).

Figure 1B. Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia with central dilated gland and smaller glands proliferating along the periphery, similar to pancreatic ducts (H&E 40×)

Figure 1C. Goblet cell and neurosecretory-like granules in glands of gastric type adenocarcinoma (H&E 200×)

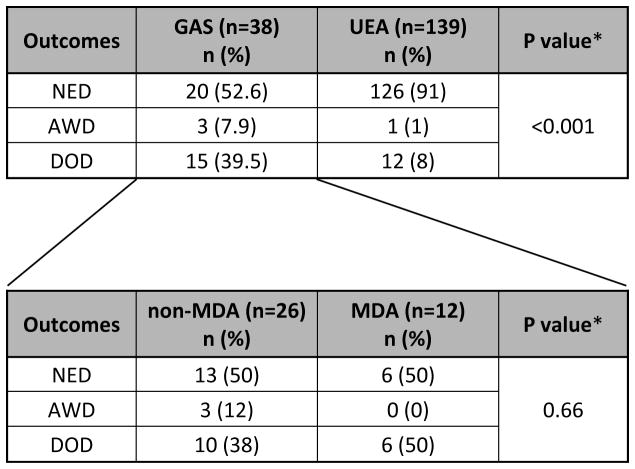

The mean age at time of GAS diagnosis was 49.8 years (range, 30.3 to 66.8 years), and the mean follow-up period was 33.9 months (range, 1.4 to 136.0 months). Twenty out of 38 (52.6%) patients showed no evidence of disease (NED), 3/38 (7.9%) were alive with disease (AWD), and 15/38 (39.5%) had died of disease. Separating non-MDA from MDA gastric-type adenocarcinomas revealed similar results between the two groups: mean age 49 vs 49.8; NED 13/26 (50%) vs 6/12 (50%); AWD 3/26 (12%) vs 0/12 (0%); and DOD 10/26 (38%) vs 6/12 (50%) respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of clinical outcomes

2-sided exact

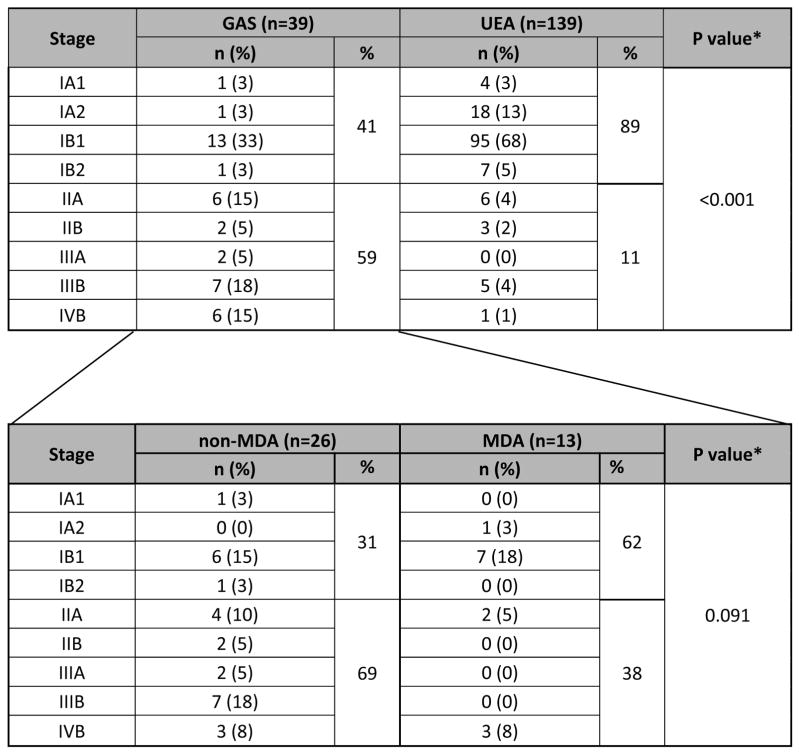

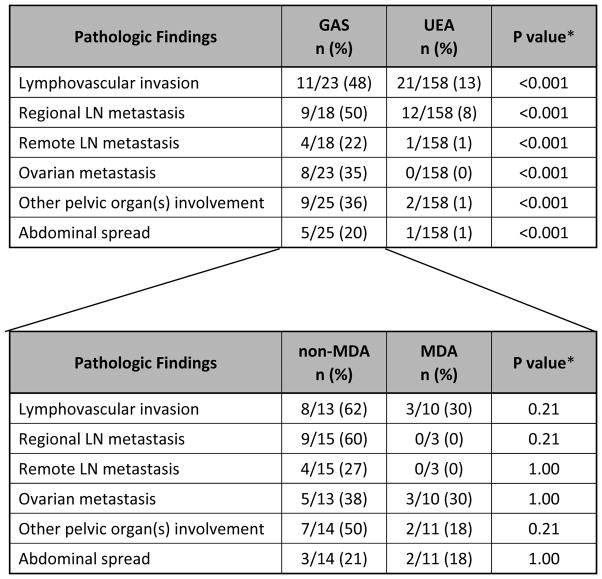

In comparison, treatment and clinical follow-up information was available in 139 UEA cases. The mean age at time of diagnosis for UEA was 40.5 years (range, 18.2 to 82.5). The mean follow-up period was 50.6 months (range, 1.2 to 196.1 months). One hundred twenty-six out of 139 (91%) patients were NED, 1/139 (1%) AWD, and 12/139 (8%) DOD (Table 3). Prior medical histories are summarized in Table 4. One patient had a history of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and another had a history of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Two patients had histories of breast cancer, 1 patient had history of colon cancer, 1 had Wilms tumor, pheochromocytoma, and renal cell carcinoma, and 1 patient developed a subsequent mucinous bronchioloalveolar carcinoma of the lung. The Li-Fraumeni patient also had a history of breast carcinoma. The other 33 patients had no significant past medical histories. Information regarding stage distribution at the time of initial surgery/biopsy is summarized in Table 5 and Figure 2. The majority of patients with GAS/MDA presented at advanced stage (59% stage II–IV), with only 41% presenting at stage I. Comparing non-MDA vs MDA tumors showed no statistical difference in stage at presentation (31 vs 62% stage I, 69 vs 38% stage II–IV, respectively, p=0.091). In comparison, the UEA patients mostly presented at stage I (89%), with only 11% presenting at high stage (stage information available in 139 UEA patients). This difference was statistically significant from GAS/MDA (p<0.0001). Additional routinely assessed pathologic variables included lymphovascular invasion, regional and remote lymph node involvement, ovarian and fallopian tube metastases, spread to pelvic and abdominal sites, and distant extraperitoneal spread. Notably, nearly 35% had ovarian involvement, 20% had abdominal disease, and 12% experienced extraperitoneal recurrences (see Table 6 for details). GAS tumors had higher incidences of these high risk features as compared to UEA and there was no difference between MDA and non-MDA tumors.

Table 4.

Past medical history (PMH) of GAS patients

| PMH | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| None | 33 | 82.5% |

| Peutz-Jeghers syndrome | 1 | 2.5% |

| Li-Fraumeni syndrome with breast cancer | 1 | 2.5% |

| Breast cancer | 2 | 5.0% |

| Colon cancer | 1 | 2.5% |

| Wilms + pheochromocytoma + renal cell carcinoma | 1 | 2.5% |

| Mucinous BAC lung (KRAS mutation) | 1 | 2.5% |

Table 5.

Disease stage distribution at presentation

2-sided exact

Figure 2.

Disease stage distribution at presentation (GAS vs. UEA).

Abbreviations: GAS=gastric type adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. UEA=usual endocervical adenocarcinoma.

Table 6.

Additional routinely assessed pathologic variables at presentation.

2-sided exact

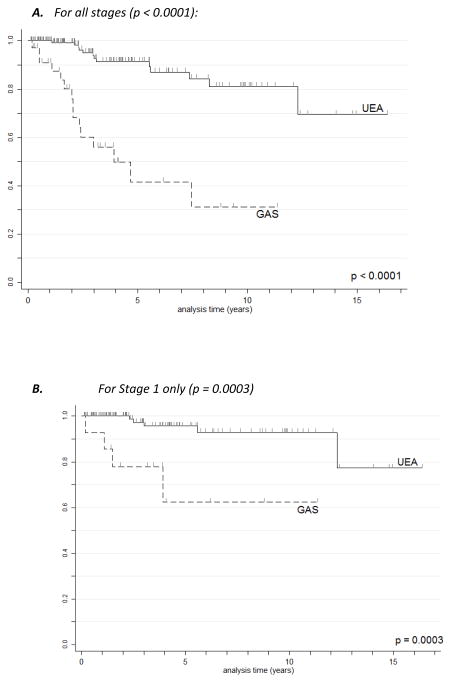

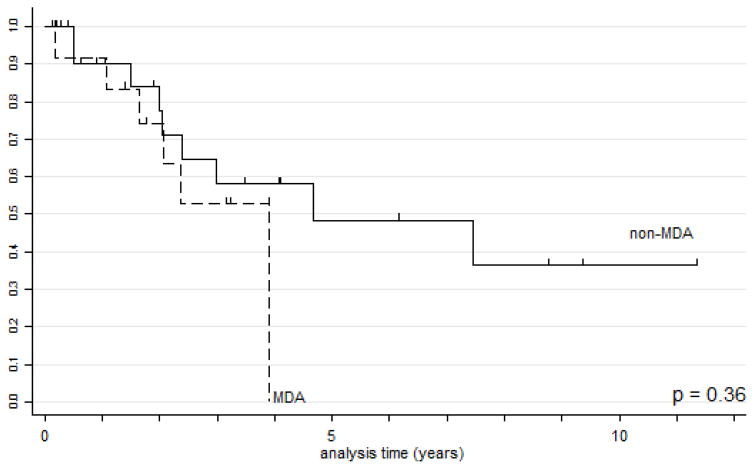

GAS had significantly worse disease specific survival (DSS) than UEA (Figs. 3A and 3B). Five- and 10-year survival data were calculated for all stages and for stage I only for both GAS and UEA (Table 7A). As expected, the 5-year DSS for stage I UEA was excellent at 96%, compared to 62% for stage I GAS. When MDA cases were extracted from the group of gastric type adenocarcinomas, there was no statistically significant difference in survival or recurrence rates based on histologic differentiation (Table 7B and Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Figure 3A. Kaplan-Meier disease-specific survival estimates for UEA vs. GAS, all stages.

Figure 3B. Kaplan-Meier disease-specific survival estimates for UEA vs. GAS, stage I only.

Abbreviations: GAS=gastric type adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. UEA=usual endocervical adenocarcinoma.

Table 7A.

Disease specific survival information (GAS vs. UEA).

| DSS | GAS (n=38) | UEA (n=139) | P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 year | 10 year | 5 year | 10 year | ||||||

| survival (%) | SE (%) | survival (%) | SE (%) | survival (%) | SE (%) | survival (%) | SE (%) | ||

| All stages | 42 | 11.5 | 31 | 12.5 | 91 | 2.9 | 81 | 5.6 | <0.0001 |

| Stage I only | 62 | 16.6 | 62 | 16.6 | 96 | 2.5 | 93 | 3.7 | 0.0003 |

SE = Standard error

Table 7B.

Disease specific survival information (MDA vs. non-MDA subtypes).

| DSS | MDA (n=12) | non-MDA (n=26) | P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 year | 10 year | 5 year | 10 year | ||||||

| survival | SE | survival | SE | survival | SE | survival | SE | ||

| All stages | 0.00 | -- | 0.00 | -- | 0.48 | 0.135 | 0.36 | 0.146 | 0.36 |

DSS - disease specific survival; SE - standard error

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier disease-specific survival estimates for MDA vs. non-MDA GAS.

Abbreviations: GAS=gastric type adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. MDA: minimal deviation adenocarcinoma.

As mentioned previously, two patients had known familial syndromes. One patient had Peutz-Jeghers syndrome with the diagnosis of endocervical adenocarcinoma (MDA including LEGH) being the sentinel event at age 39. She presented with stage IV disease (pT3b pN0 pM1) with peritoneal and omental involvement and underwent initial surgical management with supracervical hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, lymph node dissection, and peritoneal debulking, followed by chemotherapy and radiation and subsequent completion radical trachelectomy. She currently has no evidence of disease and no evidence of any other syndrome-associated neoplasia.

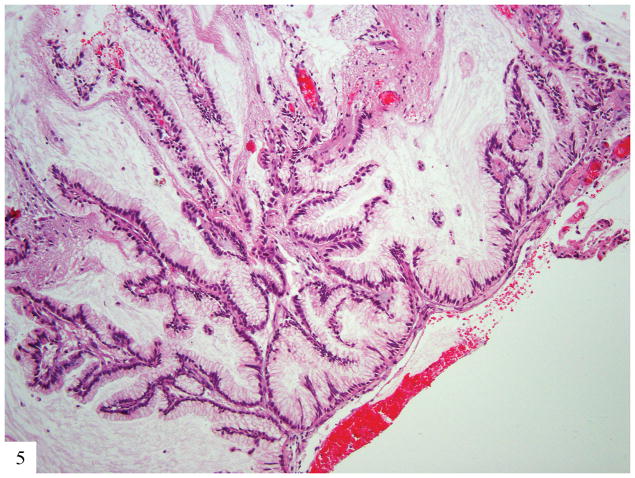

The second patient was diagnosed with Li-Fraumeni syndrome at the age of 30. She had a history of bilateral breast cancer at the age of 22, for which she was treated with bilateral mastectomy, chemotherapy, and tamoxifen. She presented with stage IIA2 GAS (pT2a2 Nx Mx) at age 30. She was initially managed with radiation and chemotherapy but within 6 months developed another malignancy, a diffuse astrocytoma (WHO grade II) that was managed with local radiation. The patient developed metastatic GAS to retroperitoneal lymph nodes 2 years later, and metastatic GAS to bone and cerebellum 2 years after that (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Metastatic gastric type adenocarcinoma to brain; tumor appears well differentiated with small basally located nuclei with little cytologic atypia infiltrating glial tissue (H&E 20×).

Twelve GAS patients developed recurrences compared to 6 UEA patients; this was statistically significant. The number of cases was small so there was no difference between GAS and UEA regarding sites of recurrence. Table 8 lists the sites of recurrence for each patient and whether they had MDA or non-MDA GAS histologic type.

Table 8.

Summary of disease recurrence

2-sided exact; bone and brain metastasis in one patient, liver and lung met in another patient

Discussion

Mucinous adenocarcinomas of the endocervix demonstrate significant clinical, etiologic, and morphological diversity and many are unassociated with HPV infection.7,8 The 2014 World Health Organization classification of mucinous endocervical adenocarcinomas lists the following subtypes: gastric, intestinal, and signet ring-cell type, with minimal deviation/adenoma malignum a synonym for gastric type adenocarcinoma when extremely well differentiated.6 Our work and that of other investigators support the conclusion that gastric type endocervical adenocarcinoma/minimal deviation adenocarcinoma constitutes a unique tumor type with distinct etiologic, morphologic, immunohistochemical, and clinical features that set it apart from other mucinous endocervical adenocarcinomas9,16,36,37 (Table 9). This work confirms conclusions offered by Kojima and colleagues and builds on them. Gastric type adenocarcinoma of the endocervix is a clinically aggressive neoplasm with a distinctive histologic appearance. Mucinous minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (adenoma malignum) is a morphologically well-differentiated variant of this tumor type. Despite a high degree of histologic differentiation, it is as clinically aggressive as less differentiated varieties. There was no significant difference in age, stage, disease distribution or outcomes between those tumors classically defined as minimal deviation adenocarcinoma vs. less well-differentiated gastric-type adenocarcinomas.

Table 9.

Comparison of GAS vs UEA

| Gastric type adenocarcinoma | Usual endocervical adenocarcinoma | |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor lesions | Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia | Adenocarcinoma in-situ |

| Location | Upper endocervical canal | Transformation zone |

| HPV associated | No | Yes |

| P16 immunohistochemistry | Negative or focal | Diffusely positive |

| Presentation | Often at high stage | Uncommonly high stage |

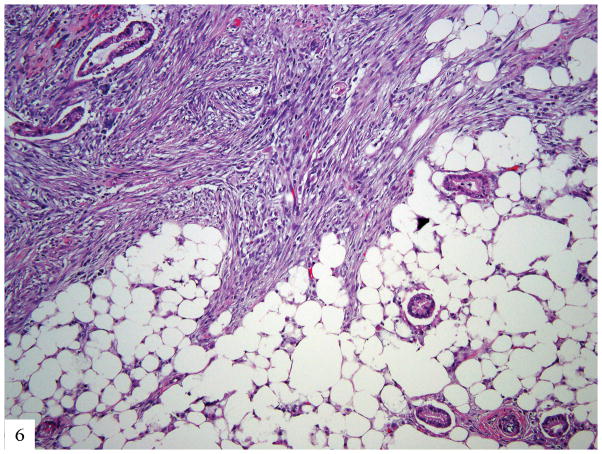

While we show that gastric type adenocarcinomas typically present at a higher stage than HPV-associated adenocarcinomas of the usual endocervical type, survival analysis restricted to FIGO stage I tumors indicates that the gastric type adenocarcinomas remain more aggressive. Unlike HPV-associated UEA, which typically remain localized to the pelvis (while sparing ovaries) and regional lymph nodes until late in the disease course, GAS frequently metastasize to ovaries, the abdomen, the omentum (Fig. 6), and distant sites. Rare affected patients have a familial cancer predisposition syndrome.

Figure 6.

Metastatic gastric type adenocarcinoma to omentum; well differentiated glands with eosinophilic and mucinous cytoplasm diffusely infiltrating adipose tissue and eliciting desmoplastic reaction (H&E 40×).

It is important for pathologists to be able to recognize this type of endocervical adenocarcinoma because of its distinguishing clinical features. With large-scale HPV vaccination programs and the projected decrease in the prevalence of HPV-associated adenocarcinomas, there is potential increase in the proportion of gastric type endocervical adenocarcinomas, making early and accurate recognition even more important. Unlike HPV-associated endocervical adenocarcinomas of usual type, gastric type adenocarcinomas, including minimal deviation type, are frequently centered in the upper endocervix,38 present with a bulky cervix,39 are usually p16-negative or focal, demonstrate gastric differentiation, and may contain lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia, its putative precursor.9,16,23,40–43 We presented a more extensive description of the morphologic spectrum of these tumors in abstract form recently (manuscript in preparation)44; we hope this helps pathologists better recognize these distinct tumors.

Similar to the data presented by Kojima’s group, we report significantly worse survival outcomes for gastric type adenocarcinoma compared to usual endocervical adenocarcinoma. Gastric type adenocarcinomas of the uterine cervix, including those traditionally classified as minimal deviation adenocarcinoma, are a distinct subset of tumors unassociated with high-risk HPV infection which have a much more aggressive phenotype and display unusual metastatic patterns compared to usual type endocervical adenocarcinoma. Patients tend to present at higher stage and, even when matched for stage I, have worse disease specific survival. Metastatic sites include omentum, liver, brain, and bone; these are uncommonly involved organs in endocervical adenocarcinoma. It is extremely important for pathologists to be able to recognize this rare tumor because of its aggressive nature and the diagnostic difficulties it can pose. Dependence on p16 reactivity to distinguish cervical adenocarcinoma from a benign process is a major pitfall in this tumor subtype. This also challenges the appropriateness of moving toward HPV-only testing as a screening tool for cervical cancer since these tumors will surely be missed by such testing alone.

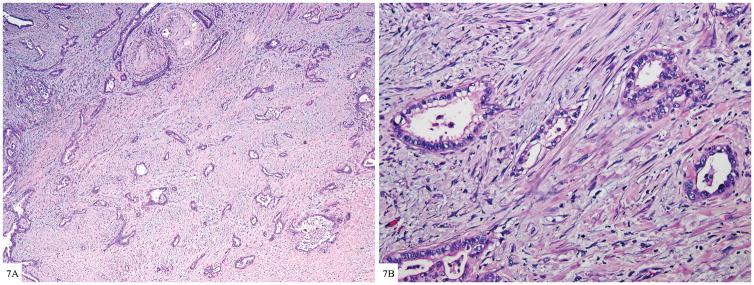

Figure 7.

Figure 7A. Well formed glands of gastric type adenocarcinoma diffusely infiltrating cervical wall (H&E 20×).

Figure 7B. Tumor shows moderate to severe nuclear atypia with voluminous clear cytoplasm and distinct cell membranes; the severe nuclear atypia is incongruous with well differentiated glands (H&E 100×)

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Bergstrom R, Sparen P, Adami HO. Trends in cancer of the cervix uteri in Sweden following cytological screening. Br J Cancer. 1999;81:159–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith HO, Tiffany MF, et al. The rising incidence of adenocarcinoma relative to squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix in the United States--a 24-year population-based study. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78:97–105. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arraiz GA, Wigle DT, Mao Y. Is cervical cancer increasing among young women in Canada? Canadian journal of public health Revue canadienne de sante publique. 1990;81:396–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chilvers C, Mant D, Pike MC. Cervical adenocarcinoma and oral contraceptives. Br Med J. 1987;295:1446–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.295.6611.1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eide TJ. Cancer of the uterine cervix in Norway by histologic type, 1970–84. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987;79:199–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurman R, Carcangiu ML, Herrington CS, et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersson S, Rylander E, Larsson B, et al. The role of human papillomavirus in cervical adenocarcinoma carcinogenesis. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:246–50. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00376-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quint KD, de Koning MN, Geraets DT, et al. Comprehensive analysis of Human Papillomavirus and Chlamydia trachomatis in in-situ and invasive cervical adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114:390–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park KJ, Kiyokawa T, Soslow RA, et al. Unusual endocervical adenocarcinomas: an immunohistochemical analysis with molecular detection of human papillomavirus. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:633–46. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31821534b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houghton O, Jamison J, Wilson R, Carson J, McCluggage WG. p16 Immunoreactivity in unusual types of cervical adenocarcinoma does not reflect human papillomavirus infection. Histopathology. 2010;57:342–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pirog EC, Kleter B, Olgac S, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus DNA in different histological subtypes of cervical adenocarcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1055–62. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64619-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilks CB, Young RH, Aguirre P, et al. Adenoma malignum (minimal deviation adenocarcinoma) of the uterine cervix. A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:717–29. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198909000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishii K, Hosaka N, Toki T, et al. A new view of the so-called adenoma malignum of the uterine cervix. Virchows Arch. 1998;432:315–22. doi: 10.1007/s004280050172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaku T, Enjoji M. Extremely well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (“adenoma malignum”) of the cervix. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1983;2:28–41. doi: 10.1097/00004347-198301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaminski PF, Norris HJ. Minimal deviation carcinoma (adenoma malignum) of the cervix. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1983;2:141–52. doi: 10.1097/00004347-198302000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kojima A, Mikami Y, Sudo T, et al. Gastric morphology and immunophenotype predict poor outcome in mucinous adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:664–72. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213434.91868.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaminski PF, Norris HJ. Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (adenoma malignum) of the cervix. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1983;2:141–53. doi: 10.1097/00004347-198302000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGowan L, Young RH, Scully RE. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome with “adenoma malignum” of the cervix. A report of two cases. Gynecol Oncol. 1980;10:125–33. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(80)90074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young RH, Welch WR, Dickersin GR, et al. Ovarian sex cord tumor with annular tubules: review of 74 cases including 27 with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and four with adenoma malignum of the cervix. Cancer. 1982;50:1384–402. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19821001)50:7<1384::aid-cncr2820500726>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCluggage WG, Harley I, Houghton JP, et al. Composite cervical adenocarcinoma composed of adenoma malignum and gastric type adenocarcinoma (dedifferentiated adenoma malignum) in a patient with Peutz Jeghers syndrome. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:935–41. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.080150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nucci MR, Clement PB, Young RH. Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia, not otherwise specified: a clinicopathologic analysis of thirteen cases of a distinctive pseudoneoplastic lesion and comparison with fourteen cases of adenoma malignum. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:886–91. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199908000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mikami Y, Hata S, Fujiwara K, et al. Florid endocervical glandular hyperplasia with intestinal and pyloric gland metaplasia: worrisome benign mimic of “adenoma malignum”. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;74:504–11. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawauchi S, Kusuda T, Liu XP, et al. Is lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia a cancerous precursor of minimal deviation adenocarcinoma?: a comparative molecular-genetic and immunohistochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1807–15. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181883722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kondo T, Hashi A, Murata S, et al. Endocervical adenocarcinomas associated with lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia: a report of four cases with histochemical and immunohistochemical analyses. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1199–210. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikami Y, Hata S, Melamed J, et al. Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia is a metaplastic process with a pyloric gland phenotype. Histopathology. 2001;39:364–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mikami Y, Kiyokawa T, Hata S, et al. Gastrointestinal immunophenotype in adenocarcinomas of the uterine cervix and related glandular lesions: a possible link between lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia/pyloric gland metaplasia and ‘adenoma malignum’. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:962–72. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mikami Y, Manabe T. Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia represents pyloric gland metaplasia? Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:323–4. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200002000-00042. author reply 5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nara M, Hashi A, Murata S, et al. Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia as a presumed precursor of cervical adenocarcinoma independent of human papillomavirus infection. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106:289–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu JY, Hashi A, Kondo T, et al. Absence of human papillomavirus infection in minimal deviation adenocarcinoma and lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2005;24:296–302. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000157918.36354.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher RA. On the interpretation of χ2 from contingency tables, and the calculation of P. J Royal Statist Soc. 1922;85:8. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaplan ELMP. Non-parametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Statist Assoc. 1958:25. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemo Reports. 1966;50:163–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peto RPJ. Asymptotically efficient rank invariant test procedures. J Roy Statist Soc A. 1972:23. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Modelling Survival Data in Medical Research. 2. London: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press LLC; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klein JPMM. Survival Analysis: Techniques for Censored and Truncated Data. 2. New York, NY: Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kusanagi Y, Kojima A, Mikami Y, et al. Absence of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) detection in endocervical adenocarcinoma with gastric morphology and phenotype. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2169–75. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pirog EC, Kleter B, Olgac S, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus DNA in different histological subtypes of cervical adenocarcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1055–62. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64619-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takatsu A, Shiozawa T, Miyamoto T, et al. Preoperative differential diagnosis of minimal deviation adenocarcinoma and lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia of the uterine cervix: a multicenter study of clinicopathology and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:1287–96. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31821f746c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park SB, Moon MH, Hong SR, et al. Adenoma malignum of the uterine cervix: ultrasonographic findings in 11 patients. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38:716–21. doi: 10.1002/uog.9078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mikami Y, McCluggage WG. Endocervical glandular lesions exhibiting gastric differentiation: an emerging spectrum of benign, premalignant, and malignant lesions. Adv Anat Pathol. 2013;20:227–37. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31829c2d66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takatsu A, Miyamoto T, Fuseya C, et al. Clonality analysis suggests that STK11 gene mutations are involved in progression of lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia (LEGH) to minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (MDA) Virchows Arch. 2013;462:645–51. doi: 10.1007/s00428-013-1417-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsuji T, Togami S, Nomoto M, et al. Uterine cervical carcinomas associated with lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia. Histopathology. 2011;59:55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mikami Y, Kiyokawa T, Hata S, et al. Gastrointestinal immunophenotype in adenocarcinomas of the uterine cervix and related glandular lesions: a possible link between lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia/pyloric gland metaplasia and ‘adenoma malignum’. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:962–72. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Conlon N, Kiyokawa T, Park KJ. Endocervical gastric-type adenocarcinoma: a detailed description of the morphologic heterogeneity of a rare entity highlighting the importance of adequate tumor sampling. Mod Pathol. 2015;28(Suppl 2):280A. [Google Scholar]