Abstract

A 28-year-old male patient with bipolar disorder taking olanzapine and lorazepam for almost 10 years presented with weight gain, diabetes, and anasarca was examined in this study. Evaluation of the patient revealed he was in heart failure. The reason for his heart failure was ambiguous and an investigation into it revealed negative results. Literature search conducted showed a few reported cases of putative olanzapine induced cardiomyopathy. One such relatively rare case is presented here.

Keywords: antipsychotics, olanzapine, cardiomyopathy, heart failure, etiology

Background

Atypical antipsychotic drug olanzapine is relatively safe when compared to its predecessor clozapine and is commonly used (1). Several side effects such as weight gain and insulin resistance, are all well documented (1). Olanzapine induced cardiomyopathy has seldom been reported.

Case Report

A 28-year-old man diagnosed to have bipolar disorder presented with atypical chest pain, New York heart association NYHA class 2 dyspnea, and generalised body swelling for a month duration. He was taking olanzapine 5 mg/day regularly and lorazepam 2 mg intermittently for the last 10 years. His psychiatric condition was fairly under control except for episodes of depression interspersed with hypomania. He also gave a history of excessive weight gain during the last six years and was started on metformin and split dose subcutaneous insulin for the last two years for diabetes. On examination his vitals were stable and he had anasarca. His complete blood count was unremarkable except for eosinophilia (absolute eosinophil count of 724/mm3). His renal function, including electrolytes and liver function test (serum albumin), were normal. He had hypercholesterolemia with 258 mg/dltriglycerides and 136 mg/dlLDL. His urine examination was normal. Chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly with grade 2 pulmonary venous hypertension and minimal pleural effusion. electrogram ECG revealed bradycardia with prolonged corrected QT (QTc) (503 milliseconds) (Figure 1). Ultrasonogram of the abdomen revealed ascites with congestive hepatomegaly. Echocardiography revealed all four chambers of the heart dilated and decreased global biventricular function (EF 20%) (Figure 2). Coronary angiography was normal. With no obvious cause, suspicion on olanzapine induced cardiac dysfunction was considered. Literature search yielded few cases of cardiomyopathy induced by olanzapine. Olanzapine was withdrawn and his blood sugar levels were kept under control. Treatment with fluid restriction, digoxin, ACE inhibitors, β-blockers, and diuretics was initiated. He gradually improved over two weeks and was discharged with oral forms of the above mentioned medication. He continues to be on a follow up for the last six months and recent echocardiography of the heart revealed mildly increased ejection fraction(EF-23%) and QTC of 455 milliseconds.

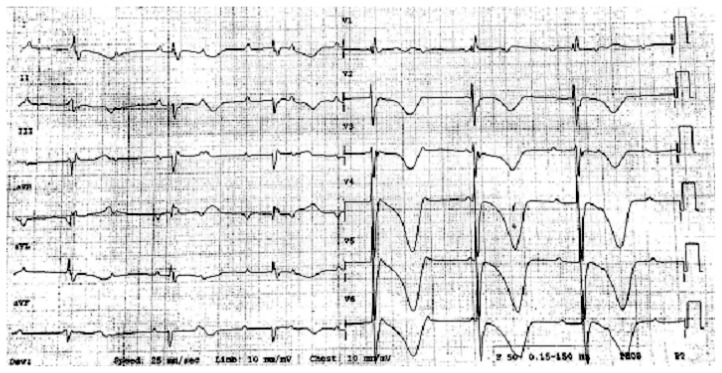

Figure 1.

ECG reveals bradycardia with prolonged QTC (503 ms).

Figure 2.

Transthoracic 2D echo showing grossly dilated heart and decreased global biventricular function.

Discussion

Cardiomyopathy is a less known side effect of antipsychotic drugs (1,2). Increased risk of myocarditis has been linked to first generation antipsychotics, such as chlorpromazine, haloperidol, and fluphenazine (1). Second generation antipsychotics, particularly clozapine has been reported to induce cardiomyopathy (3). Olanzapine, an atypical antipsychotic, structurally similar to clozapine is a thienobenzodiazepine commonly used in schizophrenia and bipolar disorders (1). These atypical antipsychotics are effective in negative psychiatric symptoms and cause less extrapyramidal side effects (1). Olanzapine became the preferred atypical antipsychotic after the dreadful hematological side effects of clozapine were known. Weight gain, impaired glucose tolerance, and hyperlipidemia are common side effects of olanzapine (4). Olanzapine seldom causes anticholinergic side effects andhematological adverse effects (4). Olanzapine is relatively less cardiotoxic among both the typical and atypical antipsychotics (1). Cardiovascular adverse effects of olanzapine include commonly postural hypotension, prolonged QT interval, and less commonly bradycardia (1,3,5). There have been sporadic anecdotal reports of cardiomyopathy produced because of the short and long term use of olanzapine (7,8), and there has been a report of olanzapine being successfully used for clozapine induced cardiomyopathy (9). The main proposed mechanism for cardiomyopathy is myocarditis and myopericarditis by direct toxicity or allergic reaction (7). As eosinophilic myocarditis seems to be the favoredetiology, blood eosinophilia should be carefully sought. However, a raised plasma level of eosinophil cationic protein, an assayable pro-inflammatory protein released from degranulated eosinophils, seems a preferable marker as it remains elevated even in cases with normal eosinophil counts (10).In animal studies, three months of olanzapine treatment was shown to induce ventricular hypertrophy of the heart (11). Furthermore, other neuroleptic drugs were shown to induce cardiac lesions comparable to those seen in toxic myocarditis. Our case presented here fits in because of the circumstantial and corroborative evidence. Our case is most likely iatrogenic, which is supported by three observations. First, the patient lacked any cardiac risk factor prior to the use of olanzapine. Second, signs and symptoms improved after discontinuation of the offending agent. Third, olanzapine was considered having a possible causal relationship because the patient had a prolonged QT interval (which normalized after drug withdrawal), hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, andeosinophilia, suggesting toxicity due to drug. Specific information about the duration of exposure to the offending agent, treatment, and prognosis are unclear. Myocardial biopsy showed only fibrosis with no inflammation or deposits in one case; however, eosinophilic infiltrate suggested hypersensitivity or anaphylaxis in others (3,6,10,11). In practice, olanzapine induced cardiac disorder should be considered in a patient who develops dyspnoea or other signs of the heart failure. Olanzapine should be withdrawn in those cases and treatment of heart failure should be done on a routine basis.

Learning Points

Olanzapine can induce cardiomyopathy in selected patients. Early recognition and cessation of the drug is required to prevent irreversible myocardial damage. Cardiac functional assessment is periodically required for the patients taking antipsychotics. Cautious use is required in patients with known heart disease.

Acknowledgement

None.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

Funds

None.

Authors’ Contributions

Conception and design: BP, JT

Analysis and interpretation of the data: BP, JT, MCN

Drafting of the article: JT, RB, MCN

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: BP, JT, RB, MCN

Final approval of the article: BP, RB

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: MCN

Collection and assembly of data: RB

References

- 1.O’Brien Patrick, Femi O. Psychotropic medication and the heart. Adv Psychiatric Treat. 2003;9(6):414–423. doi: 10.1192/apt.9.6.414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Essential Medicines and Health Products Information Portal A WHO resource OLANZAPINE - Cardiomyopathy: case report. Sweden (SE): WHO Pharmaceuticals newsletter; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hilli J, Laine K. Can olanzapine cause cardiomyopathy? Sweden (SE): Drugle, Swedish Institute for Drug Informatics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dukes MNG, Aronson JK. Meyler’s Side Effects of Drugs. 14th ed. Amsterdam (AMS): Elsevier; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee TW, Tsai SJ, Hwang JP. Severe cardiovascular side effects of olanzapine in an elderly patient: case report. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2003;33(4):399–401. doi: 10.2190/U99G-XDML-0GRG-BYE0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guillaume M, Sylvie F, Agnès S, Atul P, Maryse LM, Marie-Chritine PP, et al. Drugs and dilated cardiomyopathies: a case/noncase study in the French PharmacoVigilance Database. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69(3):287–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coulter DM, Bate A, Meyboom RH, Lindquist M, Edwards IR. Antipsychotic drugs and heart muscle disorder in international pharmacovigilance: data mining study. BMJ. 2001;322(7296):1207–1209. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7296.1207. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7296.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Citrome L, Collins JM, Nordstrom BL, Rosen Ej, Baker R, Nadkarni A, et al. Incidence of cardiovascular outcomes and diabetes mellitus among users of second-generation antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(12):1199–1206. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bobb VT, Jarskog LF, Coffey BJ. Adolescent with treatment-refractory schizophrenia and clozapine-induced cardiomyopathy managed with high-dose olanzapine. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(6):539–543. doi: 10.1089/cap.2010.2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arima M, Kanoh T, Kawano Y, Oigawa T, Yamagami S, Matsuda S. Serum levels of eosinophil cationic protein in patients with eosinophilic myocarditis. Int J Cardiol. 2002;84(1):97–99. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5273(02)00074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belhani D, Frassati D, Megard R, Tsibiribi P, Bui-Xuan B, Tabib A, et al. Cardiac lesions induced by neuroleptic drugs in the rabbit. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2006;57(3):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]