Abstract

Adolescent depressed mood is related to the development of subsequent mental health problems, and family problems have been linked to adolescent depression. Longitudinal research on adolescent depressed mood is needed to establish the unique impact of family problems independent of other potential drivers. This study tested the extent to which family conflict exacerbates depressed mood during adolescence, independent of changes in depressed mood over time, academic performance, bullying victimization, negative cognitive style, and gender. Students (13 years old) participated in a three-wave bi-national study (n = 961 from Washington State, United States, n = 981 from Victoria, Australia, 98% retention, 51% females in each sample). The model was cross-lagged and controlled for the autocorrelation of depressed mood, negative cognitive style, academic failure, and bullying victimization. Family conflict partially predicted changes in depressed mood independent of changes in depressed mood over time and the other controls. There was also evidence that family conflict and adolescent depressed mood are reciprocally related over time. Findings were closely replicated across the two samples. The study identifies potential points of intervention to interrupt the progression of depressed mood in early to middle adolescence.

Keywords: family conflict, depressed mood, adolescence, longitudinal

Introduction

Mental health problems like depression are common during adolescence, and are among the largest contributors to public health costs associated with this developmental period (Copeland, Shanahan, Costello, & Angold, 2011; Patton et al., 2014; Thapar, Collishaw, Pine, & Thapar, 2012). Adolescent depression is associated with increased risk of suicide, substance misuse, obesity, poor academic and social outcomes, and an increased risk of depressive episodes in adulthood (Chan, Kelly, & Toumbourou, 2013; Kelly, Chan, Mason, & Williams, in press; Thapar et al., 2012). However, the rates of adult mental health problems are lower when adolescent episodes are limited in number and duration (Patton et al., 2014). It is therefore important to identify potentially modifiable factors that explain continued and/or worsening adolescent depressed mood over time and that may be targeted in detection and early intervention programs (Horowitz & Garber, 2006; Stice, Shaw, Bohon, Marti, & Rohde, 2009).

The present study focused on the longitudinal role of family conflict in the exacerbation of depressed mood during early to middle adolescence. We drew upon Social Interaction Theory to understand changes in adolescent depressed mood (Hops, Lewisohn, & Roberts, 1990). On the basis of social interaction theory, stressful events in key social contexts like the family or school may trigger adolescent depression, particularly in individuals who have cognitive vulnerabilities to depression. Adolescent depressed mood is associated with disengagement and withdrawal, which may further exacerbate problems, including poor mental health, poor school performance, and family distress (Cui, Donnellan, & Conger, 2007; Davis, Sheeber, & Hops, 2002; Hofer et al., 2013). Research has identified a range of family relationship factors that are correlated with adolescent depressed mood (Restifo & Bögels, 2009), but comparatively little population-based research has focused on the longitudinal impact of family conflict on depressed mood during early to middle adolescence. The available evidence indicates that that the association of family conflict during late adolescence (16–17 years) on subsequent depression is significant but small (Fosco, Caruthers, & Dishion, 2012). Family conflict over the middle to late teenage years predicts stressful life events in young adulthood (age 21), which in turn predict subsequent depressed mood (Herrenkohl, Kosterman, Hawkins, & Mason, 2009). In one of the few studies examining links between family conflict and depressed mood within adolescence, Rueter, Scaramella, Wallace, and Conger (1999) found that changes in family conflict were related to changes in adolescent depressed mood. Other research focusing on specific points of disagreement within married couples indicates a role for adult subsystem conflict and adolescent depressed mood (Cui et al., 2007). We also know that family conflict is associated with other problems including antisocial behavior and engagement in risky behaviors (Chan et al., 2013; Cummings & Davies, 1994; Grych, 1998).

There were three key objectives of the present study. The first was to evaluate the association of family conflict and adolescent depressed mood over time, using a large sample of Australian adolescents (n = 984) and a similarly sized sample of American (Washington State) adolescents (n = 961). Both samples were followed longitudinally from age 13 to 15 approximately. We were therefore able to conservatively examine the longitudinal associations of family conflict with depressed mood by accounting for the expected stability of depressed mood over the three waves. The second objective was to evaluate the replicability of the findings by examining the strength of associations between family conflict and adolescent depressed mood across the two samples, which were closely matched socio-demographically, and participated in virtually identical surveys and procedures. Replication is a keystone of psychological research and it is relatively rare in this specific area of research (Schmidt, 2009). It is crucial to the establishment of fact because it substantially reduces the chance of Type 1 error and verifies the generalizability of findings to other samples (Schmidt, 2009; Valentine et al., 2011).

The third objective was to strengthen the validity of findings by controlling for several confounds that might account for associations between family conflict and depressed mood, or changes in depressed mood across time. We controlled for academic problems, which are related to adolescent depressed mood (Duchesne & Ratelle, 2010) and family relationship problems (Kelly et al., 2012). We also controlled for negative cognitive style (defined as the characteristic attribution of negative events to personal flaws or stable and global factors; Alloy et al., 1999; Bilsky et al., 2013). This control was included because cognitive theorists propose that it has a central etiological role in the development of depressed mood (Clark, Beck, & Alford, 1999). We controlled for bullying victimization, which is a known strong mediator of depressed mood in young adolescence (Cole et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2015). Finally, we controlled for gender, given that girls and boys show different growth patterns in depressed mood, and there is some evidence that the association of family conflict and depressed mood is stronger for girls than boys (Chan et al., 2013).

Hypotheses

The key hypothesis of the present study was that family conflict would longitudinally predict depressed mood at 15 years of age, after controlling for the autocorrelation of depressed mood (i.e., correlations in depressed mood across time) and negative cognitive style, academic performance, and bullying victimization. Given that replication is central to the establishment of fact, we evaluated the extent to which the model was comparable across the two samples. Direct replication studies are rare in the social sciences, in part because of the value placed on new observations (Bornstein, 1990; Ritchie, Wiseman, & French, 2012). To evaluate the replicability of findings, the study was based on bi-national convenience samples from the International Youth Development Study (IYDS), which includes cohorts from Washington State (WA), United States, and the State of Victoria (VIC), Australia.

Method

Participants

Data were collected from 1,945 Grade 7 students as part of the multiple-cohort, bi-national IYDS. The Grade 7 cohort was selected for the current analyses because it is the only cohort that had three waves of data in each State (WA/VIC), thus enabling matched analyses. A two-stage cluster approach was used to recruit participants for the two samples, beginning in 2001–2002. In the first stage, schools were randomly selected based on a probability proportional to grade-level size from a stratified sampling frame for all schools in the two samples. In the second stage, classes from each school for the selected grade level were randomly chosen. In VIC, 54 schools participated (81% of selected schools), and in WA, 51 schools participated (71% of selected schools). Analyses generally supported the representativeness of participating schools, with a few minor exceptions (e.g., private schools were somewhat under-represented in both samples; McMorris, Hemphill, Toumbourou, Catalano, & Patton, 2007).

Classes in VIC yielded a total of 1,301 eligible students, of whom 984 (76%) consented to and participated in the baseline survey. In WA, 1,226 students were eligible, and 961 (78%) consented and participated. Students from the Grade 7 cohort of the IYDS were followed up annually for three years with 98% retention. Tests of selective attrition have revealed small but statistically significant differences indicating that students lost to follow-up were somewhat more likely to be from Victoria, to be slightly older, and to be from slightly lower income levels (McMorris, Catalano, Kim, Toumbourou, & Hemphill, 2011). Of 1,890 students who responded to the honesty items across waves, 57 (41 in VIC and 16 in Washington) were classified as dishonest and excluded from the data set, resulting in an analysis sample of 1,833 students.

Descriptive statistics for the two samples are presented in Table 1. The sample of adolescents was predominantly age 13 when the study began (VIC M = 13.0, SD = 0.4; WA M = 13.1, SD = 0.4) and was roughly gender balanced (49% male and 51% female overall and in each sample). In terms of racial/ethnic distribution of the samples, the majority of VIC students described themselves as Australian (91%), 6% as Asian/Pacific Islander, and 1% as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. In the WA sample, 65% described themselves as White, 16% as Latino(a), 6% as Asian/Pacific Islander, 6% as Native American, and 4% as African American.

Table 1.

Key variables and controls for each sample (VIC/WA)

| VIC (N = 910) |

WA (N = 923) |

Test of state differences |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | t | df | p |

| Age 13 depressed mood | 903 | 1.54 | .40 | 914 | 1.54 | .44 | .21 | 1815.00 | .836 |

| Age 13 negative cognitive style | 891 | 2.20 | .70 | 910 | 2.17 | .75 | .99 | 1792.66 | .321 |

| Age 13 family conflict | 884 | 2.14 | .78 | 880 | 2.19 | .81 | −1.54 | 1762.00 | .125 |

| Age 13 academic failure | 881 | 1.91 | .60 | 912 | 2.10 | .71 | −6.00 | 1762.74 | .000 |

| Age 13 bullying victimization | 890 | 1.72 | .99 | 902 | 1.71 | .97 | .18 | 1790.00 | .855 |

| Age 14 negative cognitive style | 893 | 2.25 | .73 | 912 | 2.18 | .75 | 2.10 | 1803.00 | .036 |

| Age 14 family conflict | 892 | 2.20 | .77 | 918 | 2.26 | .79 | −1.54 | 1808.00 | .124 |

| Age 14 academic failure | 899 | 2.07 | .67 | 916 | 2.09 | .71 | −.48 | 1809.85 | .632 |

| Age 14 bullying victimization | 906 | 1.61 | .91 | 920 | 1.49 | .84 | 2.90 | 1807.11 | .004 |

| Age 15 depressed mood | 899 | 1.60 | .49 | 916 | 1.56 | .49 | 1.54 | 1813.00 | .125 |

Procedure

Active parental consent was a requirement for student participation. Students completed a modified form of the Communities That Care Survey (Glaser, Van Horn, Arthur, Hawkins, & Catalano, 2005), which contained small adaptations across States to ensure semantic equivalence (McMorris et al., 2007). Surveys were administered by trained staff in classrooms and absentees were given later opportunities to complete the survey at school or by telephone. Small incentives were provided to each student. All protocols were approved by the Royal Children's Hospital Ethics Committee and the University of Washington Human Subjects Review Committee.

Measures

Depressed mood

Depressed mood was measured using the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (Angold et al., 1995). Adolescents indicated how true each of 13 statements was for them. Examples included `I felt miserable or unhappy' and `I didn't enjoy anything at all', with responses ranging from 1 (Not true) to 3 (True). Items were averaged to indicate depressed mood at each age, and alpha coefficients ranged from .86 and .89 for 13 year olds in the VIC and WA samples respectively, to .91 and .92 for 15 year olds in the VIC and WA samples respectively.

Family conflict

Family conflict was measured with three items on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Definitely true) to 4 (Definitely not true). The items were `We argue about the same things in my family over and over', `People in my family often insult and yell at each other' and `People in my family have serious arguments'. This scale was reverse scored so that higher scores reflected higher levels of family conflict, and the derived measure was the mean score for the three items. The reliability of the scale was similarly high across ages and across the two samples (α range 0.80 – 0.81), and similar to other studies (Chan et al., 2013; Kelly, Toumbourou, et al., 2011). This scale is correlated with related constructs in the expected directions (e.g., family emotional closeness; Kelly, Toumbourou, et al., 2011) and is sensitive to changes in family conflict that typically occur across adolescence (Kelly, O'Flaherty, et al., 2011).

Academic failure

Respondents rated their grades/marks for the last academic year ranging from 1 (Very Good) to 4 (Very Poor), and the extent to which their grades/marks are better than most classmates (1 YES! – definitely yes) to 4 (NO! – definitely no). Responses were averaged to compute an academic failure scale at 13 (rVIC = .51; rWA = .56) and 14 years of age (rVIC = .58; rWA = .56). This measure has established predictive validity (significantly predicts premature departure from secondary education) and items are adequately correlated (Kelly et al., 2015)

Negative cognitive style

This was measured with two items that were averaged and were adequately correlated across ages and countries at 13 (rVIC = .55, rWA = .59) and 14 years of age (rVIC = .59; rWA = .62). Items asked respondents to indicate the degree to which they blame themselves and criticize or lecture themselves on a scale ranging from 1 (NO! – definitely no) to 4 (YES! - definitely yes) (Hanninen & Aro, 1996).

Bullying victimization

To measure bullying victimization, respondents were asked `Have you been bullied recently (teased or called names, had rumors spread about you, been deliberately left out of things, threatened physically or actually hurt)?' Response options ranged from 1 (No) to 4 (Yes, most days). The measure has established reliability and predictive validity (Hemphill, Tollit, Kotevski, & Florent, 2015).

Analyses

Multiple group path analyses were conducted using the maximum likelihood robust (MLR) estimator in Mplus 7.11 (Muthen & Muthen, 2011). The MLR estimator calculates a scaled chi-square statistic (Bryant & Satorra, 2012) and robust standard errors to adjust for data characteristics, such as non-normality, that violate the assumptions of maximum likelihood estimation. The MLR estimator in Mplus also incorporates advanced full information maximum likelihood (FIML) missing data estimation to account for missingness under the assumption that missing data are missing at random (MAR). As noted, retention was high (98%) and selective attrition analyses have revealed only a few, small differences between attriters and stayers; the amount of incomplete data due to non-response was negligible. FIML has been shown to provide less biased parameter estimates than traditional missing data techniques, such as case deletion (Schafer & Graham, 2002). We also explored reciprocal associations between adolescent depressed mood and family conflict using bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals (5000 samples) to ensure results were robust to violations of the assumption of normality.

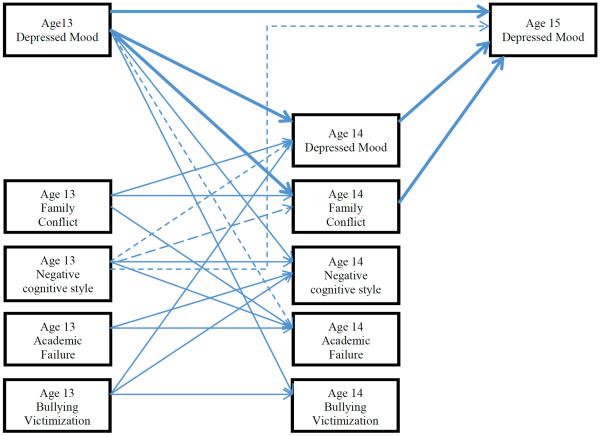

Analyses were conducted in two phases. First, an unconditional analysis was conducted with no constraints on the path estimates across the two samples. In addition to cross-lag paths, the model included autocorrelational paths for depressed mood (ages 13, 14, 15), as well as family conflict, negative cognitive style, academic failure, and bullying (ages 13 and 14) (see Figure 1). Gender (female = 1, male = 0) was built into each model as an observed independent variable. Second, we sought to verify the replicability of results across samples by testing the extent and nature of any sample differences in specific path coefficients. As previously noted, we had little clear theoretical basis for assuming a different association of family conflict and depressed mood across the two samples – rather, we were interested in threats to the replicability of key results. In an exploratory fashion, we conducted a series of constrained multiple group models in which each unconditional model path was fixed, one at a time, to equality across groups. Each constrained model was compared to the unconstrained model via the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference test (Bryant & Satorra, 2012).

Figure 1.

Final path model. All continuous lines are statistically significant (.05 > p > .001). Bold lines indicate paths of key interest in this study. This model was run on VIC and WA separately. Small dash lines indicate paths that were significant for VIC but not significant for WA. Large dash lines indicate paths that were significant for WA but not significant for VIC. Where lines are absent between adjacent constructs, paths are nonsignificant.

Results

Bivariate correlations are reported in Table 2. Of particular note, bivariate autocorrelations for depressed mood were significant and medium in size (.58 and .51 for age 13–14 years in VIC and WA respectively; .56 and .57 for age 14–15 years in VIC and WA respectively; ps > .001). The correlations between depressed mood (age 13) and family conflict (age 14), and family conflict (age 14) and depressed mood (age 15) were significant and moderate in size across the two samples (between .27 and .35, ps < .001).

Table 2.

Correlations for VIC (n = 910; upper-diagonal) and WA (n = 923; lower-diagonal)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (female) | .10** | .10** | .02 | −.05 | −.03 | .23*** | .15*** | .07* | −.02 | −.01 | .27*** | |

| 2. Age 13 depressed mood | .10** | .37*** | .40*** | .25*** | .36*** | .58*** | .29*** | .35*** | .26*** | .28*** | .47*** | |

| 3. Age 13 negative cognitive style | .07* | .34*** | .17*** | .07 | .17*** | .31*** | .44*** | .16*** | .03 | .11** | .31*** | |

| 4. Age 13 family conflict | .11** | .44*** | .19*** | .18*** | .18*** | .28*** | .14*** | .56*** | .20*** | .16*** | .21*** | |

| 5. Age 13 academic failure | −.12*** | .26*** | −.03 | .18*** | .08* | .14* | .04 | .11** | .63*** | .05 | .16*** | |

| 6. Age 13 bullying victimization | .01 | .38*** | .14*** | .26*** | .12** | .30*** | .15*** | .14*** | .04 | .48*** | .22*** | |

| 7. Age 14 depressed mood | .21*** | .51*** | .18*** | .34*** | .15*** | .23*** | .43*** | .40*** | .18*** | .36*** | .56*** | |

| 8. Age 14 negative cognitive style | .17*** | .19*** | .34*** | .16*** | −.07* | .15*** | .37*** | .26*** | .01 | .17*** | .30*** | |

| 9. Age 14 family conflict | .14*** | .27*** | .03 | .49*** | .13*** | .17*** | .39*** | .11** | .19*** | .21*** | .28*** | |

| 10. Age 14 academic failure | −.07* | .20*** | −.05 | .19*** | .71*** | .09** | .18*** | −.08* | .15*** | .06 | .18*** | |

| 11. Age 14 bullying victimization | .02 | .28*** | .10** | .18*** | .11** | .39*** | .34*** | .14*** | .14*** | .12** | .19*** | |

| 12. Age 15 depressed mood | .29*** | .45*** | .15*** | .31*** | .11** | .20*** | .57*** | .27*** | .31*** | .11** | .21*** |

Notes. Calculated using Mplus missing data estimation.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

In Figure 1, a summary of the final partially constrained model is presented, X2 (29 df, N = 1,833) = 31.08, p = .36, CFI = 1.0, RMSEA = .01. The summary captures the significance of each path across the samples by highlighting where findings were consistently significant, inconsistent (present in one sample but not the other), or consistently nonsignificant. We combined results for the two samples in to a single figure because there were few significant differences across the two samples (6 of 35 tested constraints were significant). Unstandardized coefficients (and standard errors) for paths involving the key variables (depressed mood/family conflict) are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Sample-split unstandardized path coefficients and standard errors for paths linked to age 15 depressed mood, age 14 family conflict, and age 14 depressed mood

| VIC | WA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Estimate | SE | p value | Estimate | SE | p value | ||

| Age 15 depressed mood | Age 13 depressed mood | .22 | .04 | *** | .22 | .04 | *** |

| Age 14 depressed mood | .38 | .03 | *** | .38 | .03 | *** | |

| Age 14 neg cog style | .03 | .02 | ns | .02 | .02 | ns | |

| Age 14 family conflict | .03 | .02 | * | .03 | .02 | * | |

| Age 14 academic failure | .01 | .02 | ns | .01 | .02 | ns | |

| Age 14 bullying victim | −.01 | .01 | ns | −.01 | .01 | ns | |

| Gender (reference male = 0) | .14 | .03 | *** | .18 | .03 | *** | |

| Age 14 family conflict | Age 13 depressed mood | .19 | .05 | ** | .19 | .05 | *** |

| Age 13 neg cog stylea | .04 | .03 | ns | −.12 | .03 | *** | |

| Age 13 family conflict | .47 | .02 | *** | .47 | .02 | *** | |

| Age 13 academic failure | .01 | .03 | ns | .01 | .03 | ns | |

| Age 13 bullying victim | .01 | .02 | ns | .01 | .02 | ns | |

| Gender (reference male = 0) | .07 | .04 | ns | .13 | .05 | ** | |

| Age 14 depressed mood | Age 13 depressed mood | .51 | .03 | *** | .51 | .03 | *** |

| Age 13 neg cog stylea | .08 | .02 | *** | −.01 | .02 | ns | |

| Age 13 family conflict | .05 | .02 | *** | .05 | .02 | *** | |

| Age 13 academic failure | .02 | .02 | ns | .02 | .02 | ns | |

| Age 14 bullying victim | .04 | .01 | ** | .04 | .01 | ** | |

| Gender (reference male = 0) | .17 | .03 | *** | .15 | .03 | *** | |

Notes. Bold lines indicate paths relating to the key hypothesis, ns = nonsignificant.

Path significantly different across states.

Neg cog style = negative cognitive style.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Path coefficients and standard errors for paths relating to depressed mood and family conflict are presented in Table 3 and summarized here. For students in both VIC and WA, paths between depressed mood at ages 13, 14 and 15 were statistically significant. Depressed mood at age 13 positively predicted family conflict at age 14, and paths between depressed mood (age 13) and family conflict (age 14), and between family conflict (age 14) and depressed mood (age 15) were also significant and positive. In terms of the association of depressed mood at ages 13 and 15 in both VIC and WA samples, there was a specific indirect effect for age 14 family conflict [B = .006 (95% CIs: .001, .02)]. This is consistent with the possibility that depressed mood (age 13 predicts increased family conflict (age 14), and family conflict predicts increased adolescent depressed mood (age 15). Paths were nonsignificant between age 15 depressed mood and 14 negative cognitive style/academic failure/bullying victimization, so the data were inconsistent with the possibility that these variables have a reciprocal association over time. The effects of age 13 depressed mood on age 14 family conflict were independent of age 13 family conflict. The effect of age 13 family conflict on age 14 depressed mood was independent of age 13 depressed mood. The autocorrelations for family conflict, academic failure, negative cognitive style, and bullying victimization across ages 13 to 14 years were significant and medium in size (standardized betas .38 – .61).

We conducted exploratory analyses of gender differences in the association of family conflict and adolescent depressed mood (results available on request), given mixed evidence that family conflict has been found to be more related to depressed mood amongst girls than for boys (Chan et al., 2013; Cui et al., 2007). We found that there were many more similarities than differences in the path coefficients for each gender and the few gender differences that were found could have arisen by chance given the number of tests. Importantly, none of the gender differences involved the association of family conflict and depressed mood. There were two unexpected findings for paths between age 13 and 14: Negative cognitive style was associated with decreased academic failure for students in both countries, and negative cognitive style was also associated with decreased family conflict for students in WA. Taken together, the predictors, including early adolescent depressed mood, accounted for 39% of the variance in depressed mood at age 15 for both VIC students and WA students.

Discussion

Based on three-waves of longitudinal data from two countries, the key objectives of the study were to examine the role of family conflict in predicting depressed mood amongst young adolescents, to verify the replicability of findings across two samples, and to account for viable alternative mechanisms that might explain any association of family conflict and adolescent depressed mood. There was support for the key hypothesis – family conflict at age 14 predicted adolescent depressed mood at 15 years of age independent of depressed mood at 13 and 14 years of age. The finding was independent of effects for academic performance, bullying, cognitive style and gender, and findings were closely replicated across the two samples. There was also evidence that adolescent depressed mood increased subsequent family conflict, and family conflict increased subsequent adolescent depressed mood. The latter finding is consistent with other longitudinal research on young adolescent samples showing a reciprocal association between marital conflict and depressed mood (Cui et al., 2007) and an association between mothers' anger and subsequent adolescent internalizing (Hofer et al., 2013).

The findings of this study strengthen confidence that the association of family conflict and depressed mood is not simply an artefact of changes in depressed mood or tendency toward self-blame, or the impact of stressors outside the family, including school-related factors (academic performance or bullying). In contrast to earlier research examining medium to long term associations between various marital and family problems and subsequent depressive disorders, this research shows that dynamic links between family conflict and depressed mood are present across a relatively short and early developmental period (13–15 years of age). Furthermore, the demonstration of direct replication is relatively rare in this field of research and increases our confidence that these findings were not attributable to chance associations. The generalizability of findings across the samples supports our prior findings that adolescent development influences tend to be more cross-nationally similar than different in the US and Australia (Beyers, Toumbourou, Catalano, Arthur, & Hawkins, 2004; Hemphill et al., 2011).

The present study points to the value of further research on the dynamics of family conflict and its association with adolescent depressed mood. The prospective link between depressed mood and family conflict is consistent with the possibility that adolescent disengagement from family life engenders parent stress/frustration (Roubinov & Luecken, 2013) or that depressed adolescents perceive family conflict as more severe/common than it actually is (Latendresse et al., 2009). The prospective association of family conflict and subsequent depressed mood is consistent with evidence that family conflict erodes relationship dimensions that are protective, such as perceived support, emotional responsivity, and effective problem solving (Kelly, Fincham, & Beach, 2003; Steinberg, 2001). The measure of family conflict was oriented toward dysfunctional conflict behaviors (i.e., yelling/insulting), and this was related to depressed mood over time. More research is needed on conflict resolution behaviors that reduce the impact of conflict on adolescent depressed mood (i.e., termed 'positive conflict responses', e.g., validation/praise; Hofer et al., 2013) and family relationship dimensions (e.g., emotionally secure, close, and safe parent-child relationships) that may offset any negative consequences of family conflict.

The reciprocal association of depressed mood and family conflict points to a problematic cycle that may be responsive to family-oriented prevention or early intervention approaches. Although school-based prevention programs for adolescent depression generally have limited efficacy (Merry & Spence, 2007; Sawyer et al., 2010), there is good initial evidence that combined parent training and curriculum-based resilience training is effective in reducing depressed mood (Shochet et al., 2001). The results of this study lend further support to the need for parent-focused prevention modalities for adolescent depression. Engaging parents in intensive effective conflict management and problem solving is likely to be a challenging universal prevention strategy, but brief on-line education on conflict management for parents may be cost-effective.

Although the study is longitudinal and accounts for several competing explanations, causality cannot be established. The effect for family conflict may be a result of underlying biological factors (e.g., genetic predispositions to depressed mood and family distress) or other unmeasured psychosocial variables. Conclusions may not generalize to effects for family conflict that exist within particular dyads or family subsystems. There were some peripheral findings, mainly related to negative cognitive style (age 13), that were opposite in direction to that expected [related to better academic performance at age 14, and reduced family conflict (WA only)]. The first unexpected finding may be because anxiety associated with negative cognitive styles drives higher academic performance in the short term. The second unexpected finding may be because self-blame and criticality are associated with retreat from or avoidance of parents, so there are fewer opportunities for conflict with parents. Caution is needed because there were variations in significance across the samples and the reliability index for negative cognitive style was comparatively low and variability in scores for cognitive style may have been different had a richer operationalization been employed. Despite having the strengths of a longitudinal design, three waves, large samples, and low attrition, the study has limitations. Data was collected via adolescent self-report and active parental consent mechanisms may have led to biased samples (Kelly & Halford, 2007). This may have contributed to bias in the results, particularly given that depressed mood can color adolescents' relationship perceptions. Some controls (notably bullying victimization and academic performance) were based on one or two items only, so results for these constructs should be cautiously considered.

Conclusion

Family conflict uniquely predicted depressed mood during early adolescence, and there was evidence of reciprocal relationships between depressed mood and family conflict over time. The findings were independent of the autocorrelation of depressed mood and fixed (age 13) effects, and the effects were replicated across the bi-national samples. Universal and indicated prevention programs that target family conflict may strengthen school-based programs that focus on depression.

Acknowledgments

Funding. The authors are grateful for the financial support of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA012140-05) for the International Youth Development Study and the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (R01AA017188-01) for analysis of the alcohol data. Continued data collection in Victoria has been supported by funding from Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Projects (DPO663371, DPO877359, DP1095744) and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (Project 594793). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute On Drug Abuse, National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse, the National Institutes of Health, ARC or NHMRC. Data analysis was supported by ARC Discovery Project DP130102015 to A. B. Kelly (chief investigator).

Biographies

Adrian B. Kelly is a Principal Research Fellow at The University of Queensland (UQ). He is a clinical psychologist with a PhD from UQ. His primary research interest is the role of families and communities in healthy adolescent development.

W. Alex Mason PhD is Director of Research at the National Research Institute for Child and Family Studies, Omaha. He is interested in adolescent development, substance misuse and family-based prevention.

Mary B. Chmelka is a Senior Research Analyst at (Boys Town) at the National Research Institute for Child and Family Studies, Omaha. Mary is interested in survey and program evaluation, including longitudinal structural equation modeling.

Todd I. Herrenkohl PhD is a Professor at the School of Social Work, The University of Washington (UW). He has a PhD from UW and has research interests in adolescent adjustment problems and positive youth development.

Min Jung Kim PhD is an assistant professor at Kangnam University in South Korea. She is a social work researcher with a PhD from University of Washington, School of Social Work. Her primary research interest is promotion of positive youth development and prevention of problem behavior.

George C. Patton PhD is a medically qualified epidemiologist with a clinical background in child and adolescent psychiatry. He is a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Principal Research Fellow at the Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne.

Sheryl A. Hemphill PhD is a Professor of Psychology at Australian Catholic University. She is interested in adolescent social and emotional development and the promotion of mental health.

John W. Toumbourou PhD is the Leader of Prevention Science at the Centre for Social and Early Emotional Development, Deakin University, Melbourne. He is interested in community-level prevention of alcohol use and misuse during adolescence.

Richard F. Catalano PhD is Bartley Dobb Professor for the Study and Prevention of Violence and the co-founder of the Social Development Research Group (University of Washington). has research interests in social developmental models of prevention. His interests are in the predictors of positive and problem development, and health promotion.

Footnotes

Author Contributions ABK had the primary role in manuscript writing. WAM contributed to conceptualization and completed statistical modeling. MBC and TIH provided substantial contributions to the design and development of the manuscript. MJK reviewed the manuscript and contributed to its design. GCP, SAH and JWT guided the theoretical contribution and the analytic method, and were lead investigators on the study on which this manuscript is based. RFC provided critical review and feedback on the manuscript and was a chief investigator on the project on which the manuscript is based. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest The authors report no conflict of interests.

Compliance with Ethical Standards Ethical approval. This research was approved by the UW Institutional Review Board and the Human Research Ethics Committee, Royal Childrens Hospital.

Informed consent. All parents provided informed consent for participation of their child in the study.

References

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Whitehouse WG, Hogan ME, Tashman NA, L. Steinberg D, Donovan P. Depressogenic cognitive styles: predictive validity, information processing and personality characteristics, and developmental origins. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1999;37(6):503–531. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00157-0. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, Pickles A, Winder F, Silver D. Development of a Short Questionnaire for Use in Epidemiological Studies of Depression in Children and Adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1995;5(4):237–250. [Google Scholar]

- Beyers JM, Toumbourou JW, Catalano RF, Arthur MW, Hawkins JD. A cross-national comparison of risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use: The United States and Australia. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsky SA, Cole DA, Dukewich TL, Martin NC, Sinclair KR, Tran CV, Maxwell MA. Does supportive parenting mitigate the longitudinal effects of peer victimization on depressive thoughts and symptoms in children? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:406–419. doi: 10.1037/a0032501. doi: 10.1037/a0032501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein RF. Publication politics, experimenter bias and the replication process in social science research. Journal of Social Behavior & Personality. 1990;5(4):71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant FB, Satorra A. Principles and practice of scaled difference chi-square testing. Structural Equation Modeling. 2012;19:372–398. [Google Scholar]

- Chan GCK, Kelly AB, Toumbourou JW. Accounting for the association of family conflict and very young adolescent female alcohol use: The role of depressed mood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74(3):396–505. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DA, Beck AT, Alford BA. Scientific foundations of cognitive theory and therapy of depression. John Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Dukewich TL, Roeder K, Sinclair KR, McMillan J, Will E, Felton JW. Linking peer victimization to the development of depressive self-schemas in children and adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42(1):149–160. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9769-1. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9769-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland W, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, Angold A. Cumulative Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders by Young Adulthood: A Prospective Cohort Analysis from the Great Smoky Mountain Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(3):252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.12.014. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Donnellan MB, Conger RD. Reciprocal influences between parents' marital problems and adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(6):1544–1552. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1544. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Children and marital conflict: The impact of family dispute and resolution. Guilford; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Davis B, Sheeber L, Hops H. Coercive family processes and adolescent depression. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC, US: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne S, Ratelle C. Parental behaviors and adolescents' achievement goals at the beginning of middle school: Emotional problems as potential mediators. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2010;102(2):497–507. doi: 10.1037/a0019320. [Google Scholar]

- Fosco GM, Caruthers AS, Dishion TJ. A six-year predictive test of adolescent family relationship quality and effortful control pathways to emerging adult social and emotional health. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:565–575. doi: 10.1037/a0028873. doi: 10.1037/a0028873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser RR, Van Horn ML, Arthur MW, Hawkins JD, Catalano P. Measurement properties of the Communities that Care Youth Survey across demographic groups. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2005;21:73–102. doi: 10.1007/s10940-004-1788-1. [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH. Children's appraisals of interparental conflict: Situational and contextual influences. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12(3):437–453. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.12.3.437. [Google Scholar]

- Hanninen V, Aro H. Sex differences in coping and depression among young adults. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43(10):1453–1460. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill SA, Heerde JA, Herrenkohl TI, Patton GC, Toumbourou JW, Catalano RF. Risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use in Washington State, United States and Victoria, Australia: A longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill SA, Tollit M, Kotevski A, Florent A. Bullying in schools: Rates, correlates and impact on mental health. In: Levav JLI, editor. Violence and mental health: Its manifold faces. Springer Science + Business Media; New York, NY, US: 2015. pp. 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Mason WA. Effects of growth in family conflict in adolescence on adult depressive symptoms: Mediating and moderating effects of stress and school bonding. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44(2):146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.07.005. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer C, Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Morris AS, Gershoff E, Valiente C, Eggum ND. Mother-Adolescent Conflict: Stability, Change, and Relations with Externalizing and Internalizing Behavior Problems. Social Development. 2013;22(2):259–279. doi: 10.1111/sode.12012. doi: 10.1111/sode.12012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hops H, Lewisohn PM, Roberts RE. Psychological Correlates of Depressive Symptomology Among High School Students. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1990;19(3):211–220. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp1903_3. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz JL, Garber J. The prevention of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:401–415. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.401. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AB, Chan GCK, Mason WA, Williams JW. The relationship between psychological distress and adolescent polydrug use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/adb0000068. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AB, Evans-Whipp TJ, Smith R, Chan GCK, Toumbourou JW, Patton GC, Catalano RF. Adolescent polydrug use and high school noncompletion: A longitudinal study. Addiction. 2015 doi: 10.1111/add.12829. doi: 10.1111/add.12829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AB, Fincham FD, Beach SRH. Communication skills in couples: A review and discussion of emerging perspectives. In: Burleson JOGBR, editor. The Handbook of Communication and Social Interaction Skills. Erlbaum; New Jersey: 2003. pp. 723–752. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AB, Halford WK. Responses to ethical challenges in conducting research with Australian adolescents. Australian Journal of Psychology. 2007;59(1):24–33. doi: 10.1080/00049530600944358. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AB, O'Flaherty M, Toumbourou JW, Connor JP, Hemphill SA, Catalano RF. Gender differences in the impact of families on alcohol use: A lagged longitudinal study of early adolescents. Addiction. 2011;106(8):1427–1436. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AB, O'Flaherty M, Toumbourou JW, Homel R, Patton GC, White A, Williams J. The influence of families on early adolescent school connectedness: evidence that this association varies with adolescent involvement in peer drinking networks. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:437–447. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9577-4. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9577-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AB, Toumbourou JW, O'Flaherty M, Patton GC, Homel R, Connor JP, Williams J. Family relationship quality and early alcohol use: Evidence for gender-specific risk processes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72(3):399–407. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latendresse SJ, Rose RJ, Viken RJ, Pulkkinen L, Kaprio J, Dick DM. Parental socialization and adolescents' alcohol use behaviors: Predictive disparities in parents' versus adolescents' perceptions of the parenting environment. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38(2):232–244. doi: 10.1080/15374410802698404. doi: 10.1080/15374410802698404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMorris BJ, Hemphill SA, Toumbourou JW, Catalano RC, Patton GC. Prevalence of substance use and delinquent behavior in adolescents from Victoria, Australia and Washington, USA. Health Education and Behavior. 2007;34:634–650. doi: 10.1177/1090198106286272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merry SN, Spence SH. Attempting to prevent depression in youth: A systematic review of the evidence. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2007;1(2):128–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2007.00030.x. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen BO, Muthen LC. Mplus Version 7.11. Muthen and Muthen; Los Angeles: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Romaniuk H, Mackinnon A, Carlin JB, Degenhardt L, Moran P. The prognosis of common mental disorders in adolescents: a 14-year prospective cohort study. The Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1404–1411. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62116-9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restifo K, Bögels S. Family processes in the development of youth depression: Translating the evidence to treatment. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(4):294–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.005. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie SJ, Wiseman R, French CC. Replication, replication, replication. The Psychologist. 2012;25(5):346–348. [Google Scholar]

- Roubinov DS, Luecken LJ. Family conflict in childhood and adolescence and depressive symptoms in emerging adulthood: Mediation by disengagement coping. 2013. Press release. [Google Scholar]

- Rueter MA, Scaramella L, Wallace L, Conger RD. FIrst onset of depressive or anxiety disorders predicted by the longitudinal course of internalizing symptoms and parent-adolescent disagreements. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56(8):726–732. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.8.726. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.8.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer MG, Harchak TF, Spence SH, Bond L, Graetz B, Kay D, Sheffield J. School-based prevention of depression: A 2-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of the beyondblue schools research initiative. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.007. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.2.147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S. Shall we really do it again? The powerful concept of replication is neglected in the social sciences. Review of General Psychology. 2009;13(2):90–100. doi: 10.1037/a0015108. [Google Scholar]

- Shochet IM, Dadds MR, Holland D, Whitefield K, Harnett P, Osgarby SM. The efficacy of a universal school-based program to prevent adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:303–315. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Shaw H, Bohon C, Marti CN, Rohde P. A meta-analytic review of depression prevention programs for children and adolescents: Factors that predict magnitude of intervention effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:486–503. doi: 10.1037/a0015168. doi: 10.1037/a0015168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, Thapar AK. Depression in adolescence. The Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1056–1067. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60871-4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60871-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas HJ, Chan GC, Scott JG, Connor JP, Kelly AB, Williams J. Association of different forms of bullying victimisation with adolescents' psychological distress and reduced emotional wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0004867415600076. doi: 10.1177/0004867415600076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JC, Biglan A, Boruch RF, Castro FG, Collins LM, Flay BR, Schinke SP. Replication in prevention science. Prevention Science. 2011;12(2):103–117. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0217-6. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]