ABSTRACT

Currently, the global citrus production is declining due to the spread of Huanglongbing (HLB). HLB, otherwise known as citrus greening, is caused by Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus (CLas) and is transmitted by the Asian citrus psyllids (ACP), Diaphorina citri Kuwayama. ACP transmits CLas bacterium while feeding on the citrus phloem sap. Multiplication of CLas in the phloem of citrus indicates that the sap contains all the essential nutrients needed for CLas. In this study, we investigated the micro- and macro-nutrients, nucleotides, and others secondary metabolites of phloem sap from pineapple sweet orange. The micro- and macro-nutrients were analyzed using inductively coupled plasma-mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS) and inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES). Nucleotides and other secondary metabolites analysis was accomplished by reversed phase HPLC coupled with UV, fluorescence detection, or negative mode electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). Calcium (89 mM) was the highest element followed by potassium (38.8 mM) and phosphorous (24 mM). Magnesium and sulfur were also abundant and their concentrations were 15 and 9 mM, respectively. The rest of the elements were found in low amounts (< 2mM). The concentrations of ATP, ADP, and AMP were 16, 31, and 3 µ mole/Kg fwt, respectively. GTP, GMP. NAD, FMN, FAD, and riboflavin were found at concentrations below (3 µ mole/Kg fwt). The phloem was rich in nomilin 124 mM and limonin 176 µ mole/Kg fwt. Hesperidin, vicenin-2, sinensetin, and nobiletin were the most predominant flavonoids. In addition, several hydroxycinnamates were detected. The results of this study will increase our knowledge about the nature and the chemical composition of citrus phloem sap.

KEYWORDS: Candidatus liberibacter asiaticus, flavonoids, hydroxycinnamates, huanglongbing, limonoids, nucleotides, phloem sap composition, sweet orange

Introduction

Citrus is one of the major fruit crops in the world and is grown in more than 140 countries.1 China, Brazil, the USA, India, Mexico, and Spain are the main citrus producers in the world.1 Unfortunately, global citrus production is declining due to citrus greening disease which is also known as Huanglongbing (HLB). HLB is caused by Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus (CLas) which is transmitted by the Asian citrus psyllids (ACP), Diaphorina citri Kuwayama.2 The symptoms of HLB on the leaves are characterized by a yellow blotchy mottle, or asymmetrical chlorosis, and the affected fruits are often under-developed, lopsided, and green colored with aborted or stained seeds.3 Symptomatic fruits are more acidic, and have lower total soluble solids (TSS) and juice content compared to normal fruits.4 As the disease severity increases, yield decreases due to fruit drop and tree death.5 The citrus greening disease has seriously damaged Florida's citrus industry and its agricultural economy.6

ACP transmits CLas while feeding on the citrus phloem sap. Citrus and close citrus relative species are the main hosts of ACP.2 Field observations indicated that sweet orange and Murraya paniculata (L.) Jack (orange jasmine) were the most preferred host for ACP, while Poncirus trifoliata was an occasional host.2 Acquisition access period (AAP) for CLas by ACP generally ranges from 1-7 d.7 The real time- polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) showed that the level of CLas titer was higher in nymphs compared to adults and it increases with longer AAP and post-acquisition time. These findings indicated that CLas bacterium replicates in its vector (ACP).7 CLas is a phloem-limited gram-negative bacterium that has not been cultured in vitro yet.8 CLas virulence mechanism is not fully understood; however, different mechanisms have been proposed including blocking and destruction of the phloem sap, metabolic imbalances by nutrient depletion, manipulation of phytohormones, and suppressing of plant defense.9 CLas genome is relatively small and it cannot synthesize many metabolites including essential amino acids.9 Interestingly, CLas contains many ABC transporter proteins and can use these transporters to import metabolites and enzyme cofactors from its host.9

Because the citrus phloem sap supports the growth of CLas and ACP, the citrus phloem sap is expected to have all the nutrients requirements for both of them. Consequently, characterization of the citrus phloem sap composition could reveal the nutrients required for CLas and ACP. In fact, the artificial diet of pea aphids was based upon the composition of peas extract.10 Artificial diet could be used to study ACP/CLas interaction and transmission. On the other hand, culturing of CLas is needed to fulfill Koch's postulates and may enhance research on CLas and facilitate the discovery of an effective treatment for HLB disease.

Previous studies showed that sugars and amino acids are the main components in plant phloem sap.11 Besides sugars and amino acids, plant phloem sap contains many other metabolites such as inorganic components and micronutrients, vitamins, nucleotides, phytohormones, lipids, sterols, and flavonoids.11-21 In addition, a large range of proteins were identified in the phloem sap of many plants including rice, melon, cucumber, and pumpkin.11 The previous studies showed that phloem sap is a complex mixture and contains many metabolites.

In our previous work, we investigated the phloem sap chemical composition of sweet orange.22 We found that the citrus phloem sap was rich in sugars (sucrose; 66 mM, glucose: 20 mM, and fructose; 10 mM, and inositol; 2 mM.22 The citrus phloem sap was also rich in amino acids (33-43 mM). Proline (26 mM), alanine (5 mM), asparagine (3 mM), glutamine (2 mM), and aspartic acid (1 mM) were the most predominant amino acids in the phloem sap.22 Gamma–aminobutyric acid (GABA), a non-protein amino acid, was also present in the citrus phloem sap (3 mM). Besides sugars and amino acids, many organic acids including malic (22 mM), citric (6 mM), succinic (3 mM), and benzoic acid (2 mM) were detected in the phloem sap.22

Studying of the citrus phloem sap composition and sequencing of CLas genome could enhance our understanding of the nutrient needs of this fastidious bacterium. In fact, metabolomic studies of the citrus phloem sap and genomic studies of the CLas bacterium complement each other. For example, the sequencing of the CLas genome showed that CLas cannot synthesize tyrosine, tryptophan, valine, leucine, and isoleucine from their metabolic intermediates.23 Consequently, CLas should obtain these essential amino acids from its hosts. The chemical analysis of the citrus phloem sap showed that all of these essential amino acids exist in the citrus phloem sap.22 In addition, sequencing of CLas genome showed that malate synthase and isocitrate lyase are absent in the CLas genome and CLas depends on exogenous malate, fumarate, succinate, and aspartate as carbon substrates for the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and pyruvate production.9 Analysis of the chemical composition of the citrus phloem sap showed that these intermediates were abundant in the citrus phloem sap, especially malate and succinate.22

No information is available in the scientific literature about the composition of inorganic elements, nucleotides, and other secondary metabolites in the citrus phloem sap. In the current study, we investigated these components in the phloem sap of sweet orange. The results from this study will reveal more information about chemical composition of the citrus phloem sap and the nutrients available for ACP and CLas.

Material and methods

Chemicals

Sodium hydroxide, sodium acetate, adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP) sodium salt, adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP) sodium salt, adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) disodium salt, cytidine 5′-monophosphate (CMP) disodium salt, cytidine-5′-diphosphate (CDP) disodium salt, cytidine-5′-triphosphate (CTP) disodium salt, guanosine 5′-monophosphate (GMP) disodium salt, guanosine 5′-diphosphate (GDP) sodium salt, guanosine 5′-triphosphate (GTP) sodium salt, guanosine 5′-diphosphate-β-L-fucose (GDP-Fuc) sodium salt, guanosine 5′-diphosphate-D-mannose (GDP-Man) disodium salt, uridine 5′-monophosphate (UMP) disodium salt, uridine 5′-diphosphate (UDP) sodium salt, uridine 5′-triphosphate (UTP) sodium salt, uridine 5′-diphospho-D-glucose (UDP-Glc) disodium salt, uridine 5′-diphospho-D-galactose (UDP-Gal) disodium salt, uridine 5′-diphospho-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) disodium salt, uridine 5′-diphospho-N-acetyl-D-galactosamine (UDP-GalNAc) disodium salt, B-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, oxidized form, monosodium salt (NADP), β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydrate (NAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide disodium salt hydrate (FAD), riboflavin 5′-phosphate sodium salt hydrate (FMN), inosine-5′-monophosphate disodium salt hydrate (IMP), inosine-5′-diphosphate disodium salt (IDP), inosine-5′-triphosphate trisodium salt (ITP), amino acids (phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan), nucleosides (adenosine, uridine, cytidine, guanosine) and mangiferin were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The citrus compounds, nomilin, limonin, hesperidin, feruloylputrescine, isorhoifolin, diosmin, 2′-E-O-feruloylgalactaric acid (16F), sinensetin, nobiletin, heptamethoxyflavone, and tangeretin, were isolated to purity from orange peel and used as authentic standards. Their identities and purity were confirmed by 1H NMR and HPLC-ESI-MS.24-25

Plants and phloem sap collection

Pineapple sweet orange (Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck) plants (12 months old, 0.75–1 m tall) were grown using Farafard Citrus Mix (Sun Gro Horticuluture Distribution Inc., Agawam, MA, USA) and kept in a temperature-controlled greenhouse (28–32°C). Plants were regularly watered twice a week. Three flushes (2-3 week-old) were collected from each plant from three different locations (top, middle, and bottom).

The phloem sap of the Pineapple sweet orange trees was collected using an ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-enhanced exudation technique or by centrifugation as described by Hijaz and Killiny.22 Phloem sap exudates from three different places of each tree were pooled and considered as one replicate. Five replicates were used in each assay.

Elemental analysis

ICP-MS

Potassium (K-39), magnesium (Mg-24), aluminum (Al-27), vanadium (V-51), chromium (Cr-52), manganese (Mn-55), iron (Fe-56), cobalt (Co-59), nickel (Ni-60), copper (Cu-63), zinc (Zn-66), arsenic (As-75), selenium (Se-78), molybdenum (Mo-95), silver (Ag-107), cadmium (Cd-111), barium (Ba-137), boron (B-11), thallium (Tl-205), calcium (Ca-44), sodium (Na-23) and lead (Pb-208) were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS) at Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory using Agilent ICP-MS 7500cx (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA).

Instrument settings were as follows: power: 1500 W; sample depth 8 mm; carrier gas flow rate: 0.9 L/min; make-up gas flow rate: 0.2 L/min; nebulizer pump: 0.1 rps; extract 1: 0 V; extract 2: −170 V; omega bias: −18 V; omega lens : 0V cell entrance: −30V; QP focus: 2 V, −8 V and −11 V, respectively for normal, hydrogen and helium modes; cell exit: −30 V for normal mode, and −40 V for hydrogen and helium modes; QP bias: −6 V for normal mode, and −18 V for hydrogen and helium modes; hydrogen flow rate: 3.5 ml/min; helium flow rate: 5 ml/min. ArO+ interference with Fe-56 was reduced by applying helium collision in a reaction cell. ArO+ counts below 3 counts per second during instrument tune optimization were used to indicate adequate interference removal. Counts were repeated three times, and integration times were 0.1 seconds, except for K-39 (0.005 s), Mg-24 (0.05 s), Al-27 (0.3 s), V-51 (0.5 s), Cr-52 (1 s), Ni-60 (1 s), As-75 (1 s), Se-78 (5 s) and Cd-111 (1 s).

Sample preparation: 1.0 ml of the phloem sap was mixed with 3 ml of ultrapure water (Milli-Q Biocel, Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), and 4 ml of 70% nitric acid (TraceMetal Grade, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) in a digestion cup (SC475, Environmental Express, Mt. Pleasant, SC, USA), capped, and heated (HotBlock™, Environmental Express, Mt. Pleasant, SC, USA) at 105°C for 3 h. Following digestion, samples diluted by the addition of 18 ml of water. High molecular weight isotopes, including Cd-111, Ba-137, Tl-205, and Pb-208, were analyzed without the use of reaction cell interference removal. Se-78 was analyzed in the hydrogen reaction mode, and the rest of the elements were analyzed in the helium collision mode. To account for sample matrix effects, 1 µg/L of scandium (Sc-45), rhodium (Rh-103), indium (In-115), lutetium (Lu-175), and bismuth (Bi-209) were used as fixed-concentration internal standards in all samples and calibration standards, introduced in line prior sample nebulization. The internal standard isotope with the closest mass to the isotope of interest was used for quantification. Quantification was done by count rate ratios between internal standards and the elements of interest. A series of seven standards (Environmental Express, Mt. Pleasant, SC, USA; lot number 9830809), ranging in element concentrations from 0 µg/L to 1 mg/L, were used. Element concentrations in blanks were used to correct sample-measured concentrations for background contaminants associated with analytical reagents and processing. System stability was verified by analysis of 100 µg/L and 500 µg/L standards at the beginning and end of the analysis batch. System stability was deemed acceptable at <10 % variation. Limits of detection were defined as three times the background standard deviation of a 10 µg/L standard, derived from seven independent analyses. Limits of quantification were defined as 10 times the background standard deviation of a 10 µg/L standard, derived from seven independent analyses.

ICP-OES

Phosphorus (P) and sulfur (S) were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) at the Kansas State University Soil Testing Laboratory using a Varian 720-es (Varian, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Instrument settings were as follows: power: 1200 W; plasma flow: 15 L/min; auxiliary flow: 1.5 L/min; nebulizer flow: 0.75 L/min; read time: 2 s (repeated three times), stabilization delay 15 s; P wavelength: 213.618 nm; S wavelength: 180.669. Standards for ICP-OES were obtained from Exaxol Chemical Corporation (Clearwater, FL, USA; lot number 140722). Phosphorus standard concentrations were 0 mg/L, 5 mg/L, 10 mg/L, 15 mg/L and 20 mg/L. Sulfur standard concentrations were 0 mg/L, 10 mg/L, 20 mg/L, 30 mg/L, 40 mg/L. Reference samples containing element concentrations of 1 mg/kg, prepared from commercially available standards (Environmental Express, Mt. Pleasant, SC, USA), were used for data quality assurance. As was done for ICP-MS analysis, each batch of samples included digestion/processing blanks used to correct for background concentrations.

Extraction of phloem sap nucleotides and secondary metabolites using perchloric acid

The bark was stripped into two pieces and was manually removed from the twig. The inner part of the bark was rinsed with deionized water and dried with Kim wipes to exclude any contamination from the xylem sap. Then the bark strips were cut into 1-cm pieces using a sterile razor blade and ground with liquid nitrogen using a mortar and a pestle. Approximately 0.50 g of the ground sample was transferred to a 10 mL plastic centrifuge tube and 4 mL of 0.8 M perchloric acid was added. The samples were vortexed for 1 min and then kept at 4°C for 10 minutes. The vortex step was repeated three times and the sample was centrifuged at 4000 rpm at 4°C. The supernatant was neutralized to pH 7.0 by the addition of 3 M potassium hydroxide (about 1 ml) and the samples were centrifuged again to remove any potassium chloride precipitate. The pH of the samples was rechecked and adjusted if needed by the addition of 1 M sodium hydroxide or sulfuric acid. Samples were concentrated 10 times using a Speed Vac concentrator at 35°C (Savant, Hicksville, NY). The samples were kept frozen at −20°C until analysis.

HPLC analysis of nucleotides

The detection of nucleotides was accomplished by reversed phase HPLC coupled with either UV detection at 260 nm, fluorescence detection, or negative mode ESI-MS. HPLC solvent conditions were similar to previously reported by Klawitter et al. (2007) with some modifications.26 Nucleotide separations were accomplished with an Agilent 1100 system and a Synergi 4 µm Hydro-RP 80 Å column (250 × 4.6 mm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) with linear gradients of solvent A: 1.2 mL of 88% formic acid/L formic acid (0.03M final), 0.3 mL/L dibutylamine (0.0018 M final), and ammonium hydroxide to adjust to pH 6.0 (∼4 mL) and solvent B: acetonitrile. The linear gradients were as follows: 0 min 99% A, 1% B; 35 min, 95% A, 5% B; 40 min, 70% A, 30% B; 45 min, 30% A, 70% B; 50 min, 30% A, 70% B; 60 min, 99% A, 1% B; 80 min, 99% A, 1% B with a flow rate of 1.0 ml min−1. Fluorescence detection of guanosine nucleotides was accomplished with a Shimadzu RF-535 fluorescence detector set with 285 nm excitation and 390 nm emission, with post column infusion of 0.5 N HCl at 0.10 mL min−1. Detection by MS was accomplished with an Advion CMS using negative mode ESI. Ionization source conditions were: capillary temperature 250°C, capillary voltage 180 V, source voltage 25 V, source voltage dynamic 10 V, gas temperature 250°C, Voltage 2000 V, nebulizer gas 6 L h-1. Nucleotide analyses were made using single ion monitoring of the (M-H)− m/z ions. Nucleotide stock solutions (2000 ppm) were prepared by dissolving 4.0 mg of each standard in 1 mL of water. A standard mix was prepared by mixing 100 µL of each standard. The standard mixture was further diluted with water to prepare a set of calibration standards (20, 10, 5, and 1 ppm). This standard mixture was injected into the HPLC-MS under the same assay condition to quantify the nucleotides in analyzed samples.

HPLC analysis of flavins

The detection of flavins was accomplished by reversed phase HPLC coupled with fluorescence detection in a manner similar to previously reported by Andre´s -Lacueva (1998).27 HPLC was run with a Varian Star system with 210 pump and 335 UV/Vis photodiode array detector. Flavin separations were accomplished with a Synergi 4 µm Hydro-RP 80 Å column (250 × 4.6 mm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) using linear gradients of solvent A: 0.05 M NaH2PO4 at pH 3 with H3PO4 and solvent B: acetonitrile. The linear gradients were as follows: 0 min 93% A, 7% B; 15 min, 75% A, 25% B; 20 min, 65% A, 35% B; 23 min, 65% A, 35% B; 35 min, 20% A, 80% B; 40 min, 20% A, 80% B; 45 min, 93% A, 7% B; 55 min 93% A, 7% B; with constant flow rate of 0.5 ml min−1. Fluorescence detection was accomplished with a Jasco FP2020 fluorescence detector set with gain 1.0 and using 265 nm excitation and 525 nm emission. Stock solutions of flavins standards were prepared by dissolving 3 mg of each standard in 1 mL DMSO and diluting it to 50 mL using deionized water. The calibration standards (1, 5, 10, and 20 ppm) were prepared by diluting the stock solutions with water and were used to build the calibration curves.

HPLC analysis of limonoids

Analyses of limonoids in the phloem and phloem/bark extracts were done with a Waters 2695 Alliance HPLC (Waters, Medford, MA) connected in parallel with a Waters 996 PDA detector and a Waters/Micromass ZQ single-quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization source. Compound separations were achieved with a Synergi 4 µHydro-RP 80 Å column (150 × 2.0 mm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) using linear gradients of solvent A: 0.5% aqueous formic acid and solvent B: acetonitrile. The linear gradients were as follows: 0 min, 99% A, 1% B; 10 min, 95% A, 5% B; 20 min, 80% A, 20% B; 40 min, 70% A, 30% B; 48 min, 25% A, 75% B; 53 min 25% A, 75% B; 60 min, 99% A, 1% B; 80 min 99% A, 1% B, at a constant flow rate of 0.3 ml min−1. HPLC eluant was split between the photodiode array detector and the mass spectrometer in a 10/1 ratio. UV spectra were monitored between 240 nm to 400 nm, and chromatograms were monitored at 280 nm and 330 nm. Identifications of compounds were done by absorbance and mass spectrometry, and by comparison of retention times of samples with authentic standards obtained from the repository of Hasegawa et al., (1980).24 Standardization of instrument response was monitored using (6.5 ppm final concentration) mangiferin as an internal standard in each phloem extract. MS parameters were as follows: ionization mode, positive electrospray; capillary voltage 3.0 kV; extractor voltage 5 V; source temperature 100°C; desolvation temperature 225°C; desolvation gas flow 465 L h−1; cone gas flow 70 L h−1; scan range m/z 100–900; rate 1 scan sec−1; cone voltages 20 and 40 V.

HPLC analysis of flavonoids and hydroxycinnamates

Analyses of the flavonoids and hydroxycinnamates in the phloem and phloem/bark extracts were done with a Waters 2695 Alliance HPLC (Waters, Medford, MA) connected in parallel with a Waters 996 PDA detector and a Waters/Micromass ZQ single-quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization source. Compound separations were achieved with a reversed phase XBridge C8 column (130 Å, 5 µm, 4.6 mm X 150 mm, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) using linear gradients of solvent A: 0.5% aqueous formic acid and solvent B: acetonitrile. The linear gradients were as follows: 0 min, 90% A, 10% B; 10 min, 80% A, 20% B; 15 min, 75% A, 25% B; 23 min, 40% A, 60% B; 40 min, 30% A, 70% B; 45 min 30% A, 70% B; 53 min, 90% A, 10% B; 60 min 90% A, 10% B, at a constant flow rate of 0.75 ml min−1. HPLC eluant was split between the photodiode array detector and the mass spectrometer in a 10/1 ratio. UV spectra were monitored between 240 nm to 400 nm, and chromatograms were monitored at 280 nm and 330 nm. Identifications of all reported compounds were done by absorbance and mass spectrometry, and by comparison of retention times of samples and authentic standards obtained from the repository of Horowitz and Gentili (1977).25 Quantitation of the flavonoids and hydroxycinnamates were performed with UV peak integrations at 330 nm, respectively, and with mass ion quantitation, using mangiferin (6.5 ppm final concentration) as an internal standard. The PMFs were quantified using both MS and UV absorbance detection and calibration curves with authentic standards (sinensetin, nobiletin, heptamethoxyflavone, and tangeretin). MS parameters were as follows: ionization mode, positive electrospray; capillary voltage 3.0 kV; extractor voltage 5 V; source temperature 100°C; desolvation temperature 225°C; desolvation gas flow 465 L h−1; cone gas flow 70 L h−1; scan range m/z 100-900; rate 1 scan sec−1; cone voltages 20 and 40 V. Quantification of flavonoids was done by external calibration curves obtained by injecting different amounts of stock solution containing the internal standard and all the compounds of interest.

HPLC analyses of phenolic amino acids and nucleosides

The HPLC analyses of phenolic amino acids (phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan) and nucleosides (adenosine, uridine, cytidine, guanosine) were done with the same HPLC and MS instrumentation and solvent gradients as described above for the limonoids and phenolic compounds, with the exception of the use of a Atlantis dC18 (100 Å, 5 µm, 150 × 2.1 mm, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) reversed phase column. Quantitation of the test compounds was done by both 260 nm UV peak integrations and by specific single-ion-monitoring mass detection with positive ion electrospray ionization, with the use of mangiferin (3.25 ppm final concentration) an internal standard.

Results and discussion

Elemental analysis

Elements detected in the phloem sap of pineapple sweet orange trees are listed in Table 1. Calcium was the most abundant (89.84 mM) element followed by potassium (38.83 mM) and magnesium (15 mM) (Table 1). Phosphorous and sulfur were also abundant and their concentrations in the phloem sap were 23.5 mM and 8.5 mM, respectively (Table 1). Sodium was detected in small amounts (2 mM) in the phloem sap obtained by centrifugation. However, it was not detected in the EDTA-exudate due to the presence of high level of sodium from EDTA tetra sodium salt (EDTA). Small amounts (< 0.1 mM) of Zn, Mn, Cu, Fe, Ni, and B, and only trace amounts of Mo and Ba were detected in the phloem sap of pineapple sweet orange trees (Table 1). Since the soil is the main source of elements for plants and the plants used in this experiment were grown using a specific type of soil, the elemental composition of the phloem sap from plants grown in fields could be slightly different from values reported in our study.

Table 1.

Micro- and macro-nutrients in ‘Pineapple’ sweet orange phloem sap measured using ICP (n = 5).

| Element (isotope monitored) | Centrifuge-exudate(mM) | EDTA-enhancedexudatem mol/kg fwt |

|---|---|---|

| B | 0.05 ± 0.03 | ND |

| Na | 2.20 ± 0.34 | ND |

| Mg | 15.07 ± 2.29 | 8.52 ± 4.30 |

| K | 38.83 ± 5.31 | 29.27 ± 6.7 |

| Ca | 89.84 ± 12.88 | 64.99 ± 26.05 |

| Mn | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.09 |

| Fe | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.05 |

| Ni | 0.01 ± 0.00 | Trace |

| Cu | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.02 |

| Zn | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.04 |

| Mo | Trace | ND |

| Ba | Trace | ND |

| Pa | 23.50 ± 4.90 | 13.71 ± 2.95 |

| Sa | 8.50 ± 3.95 | 2.30 ± 1.06 |

P and S were analyzed by ICP-OES, while the rest of the elements were analyzed by ICP-MS.

Macro-nutrients (N, P, K, S, Ca, and Mg) and micro-nutrients (Fe, Cu, Zn, Mo, B, and Mn) are important for citrus, and their deficiency may result in low crop growth and yields.28 Calcium (Ca) was the most predominant element in citrus phloem sap (Table 1). Calcium was reported in the phloem sap of many species and it plays an important role in cell physiology and signaling.28-30 Potassium (K), the second most abundant element, was also detected in the phloem sap of many plants such as Arabidopsis, Eucalyptus globules, and Zea mays L. and it plays an important role in sugar loading in the phloem.13,14,31 Previous studies also showed that phosphorous (P) was abundant in the phloem sap of many plants and its level varies from day to night and from season to season.11,32,33 High concentration (15 mM) of sulfur (S) was reported in the phloem sap of Arabidopsis.13 Magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), and chlorine (Cl) were also found in the phloem sap of maize, and their concentrations in leaf are controlled by the phloem transport.34 Low levels of iron (Fe), copper (Cu), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), boron (B), and molybdenum (Mo) were also reported in the phloem sap of other plants and their concentrations depend on the type of translocation mechanism.11

Most of the elements detected in the phloem sap of the pineapple sweet orange trees in this study were also found in the juice of pineapple sweet orange.35 Potassium (K) was found to be the most predominant element (18 mM), followed by P (6.7 mM).35 The concentrations of Na, Mg, Ca, and Fe in pineapple juice were 3.4, 2.6, 1.5, and 0.1 mM, respectively. Aluminum, Si, Ti, Mn, Ni, Cu, Zn, Rb, Sr, and Zr were also present in pineapple orange juice but in low levels.35

Macro-nutrients and micro-nutrients and the growth of CLas and ACP

Macro- and micro-nutrients found in the phloem sap are important for the growth of piercing-sucking insects. It is believed that Fe, Zn, Cu, and Mn are essential for insect growth and development because they act as cofactors for various enzymes of basic critical function.36 These elements in citrus phloem sap could play an important role in the growth and reproduction of citrus phloem sap feeders such as psyllids and aphids. In fact, the addition of Zn, Cu, Fe, Mg, K, P, and Mn to the synthetic diet of the green peach the aphid (Myzus persicae) supported its growth and reproduction for more than 10 months.36

Recently, Telagamsetty et al. (2015) showed that the phloem sap from new flush shoots contained higher amounts of amino acids and several macro-nutrients (P, N, and K) and micro-nutrients (Na, Cu, and Zn) than that of mature flush shoots.37 On the other hand, the phloem sap of mature flush shoots was higher in Mg, Mn, Ca, S, Fe, and B.37 Telagamsetty et al. (2015) concluded that new flush shoots were more favorable to oviposition and nymphal development than mature shoots because they are more tender and higher in essential nutrients.37

Macro- and micro-nutrients found in the phloem sap could also be important for the growth and survival of the phloem-limited bacteria like CLas. Previous studies showed that CLas-infected citrus trees showed a 35% reduction in P compared to healthy trees.38 The reduction of P in CLas-infected trees indicated that P could be required for the growth of CLas. In addition, genome analysis showed that the CLas encodes the znuABC genes responsible for the import of Zn.39 The presence of znuABC genes indicates that Zn is an essential micronutrient for CLas. It is assumed that the uptake of Zn from its host results in localized zinc deficiency in the citrus plant and consequently leads to plant death.39 This assumption has been supported by the fact that citrus greening symptoms mimic those of zinc deficiency.39

Nucleotides and nucleosides

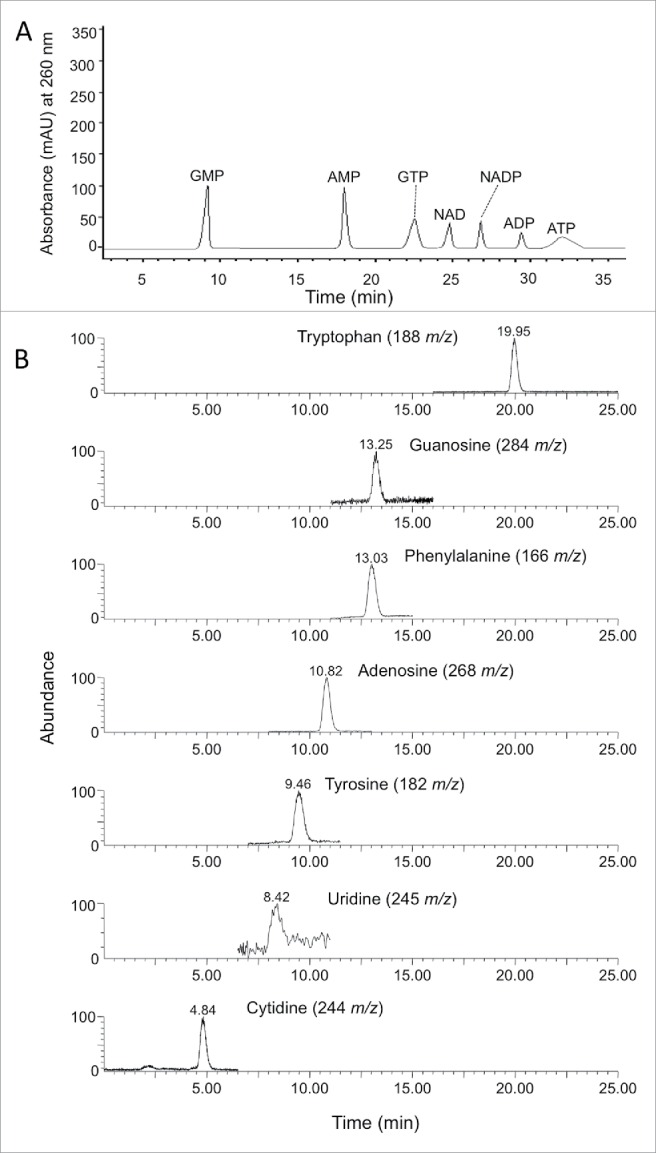

Three adenine nucleotides (ATP, ADP, and AMP), 2 guanine nucleotides (GTP and GMP), two nicotinamide nucleotides (NAD and NADP) were detected using HPLC-MS in the perchloric acid (PCA) extract of citrus phloem tissue (Table 2). The separation of these nucleotides on the Synergi Hydro-RP column column is shown in Fig. 1A. ADP was the major nucleotide (31.4 µ mole/kg fwt) followed by ATP (16.2 µ mole/kg fwt) (Table 2). The adenylated energy charge (AEC) of the citrus phloem sap was 0.65±0 .15. AMP and NADP concentrations were about 3 µmole/kg fwt, whereas the GTP, GMP, and NAD concentrations were less than 1 µ mole/kg fwt (Table 2).

Table 2.

Nucleotides and riboflavin concentration (µ mole/Kg fwt) in the phloem tissue (n = 5).

| Compound | RTa | m/z (−) monitored | EDTA-enhancedexudate | PCAb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP | 32.1 | 506 | ND | 16.2 ± 4.3 |

| ADP | 29.5 | 426 | ND | 31.4 ± 9.9 |

| AMP | 18.0 | 346 | ND | 3.0 ± 1.1 |

| GTP | 22.5 | 522 | ND | 0.7 ± 0.4 |

| GMP | 9.0 | 362 | ND | 0.7 ± 0.7 |

| NAD | 24.7 | 662 | ND | < 0.3 |

| NADP | 26.8 | 742 | ND | 3.0 ± 2.6 |

| FMN | 18.5 | λex/λem (nm) 265/525 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| FAD | 20.7 | λex/λem (nm) 265/525 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| riboflavin | 16.5 | λex/λem (nm)265/525 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 1.8 ± 0.3 |

Retention time

Perchloric acid

Figure 1.

An HPLC-UV chromatogram showing separation of nucleotide standards (A) on a Synergi Hydro-RP column, and positive ESI-MS single ion monitoring (SIM) chromatograms of nucleosides and phenolic amino acids standards (B) using Atlantis dC18 column.

None of the previous nucleotides were detected in the phloem sap obtained by centrifugation or EDTA-enhanced exudation method. On the other hand, high concentrations of adenosine, guanosine, cytidine, and uridine nucleosides were detected in the EDTA-enhanced exudate (Table 3). Separation of these nucleosides by reverse phase HPLC-EMS on Atlantis dC18 column is shown in Fig. 1B. In agreement with the previous results, low concentration of nucleosides was detected in the perchloric acid extract (Table 3) because it destroys all the enzymes present in the phloem sap and consequently prevents the breakdown of these nucleotides. Two flavin nucleotides (FMN and FAD) as well as riboflavin were detected in perchloric acid extract and EDTA-enhanced exudate (Table 2). The concentrations of riboflavin and the flavin nucleotides were less than 2 µ mole/kg fwt (Table 2).

Table 3.

Nucleosides and amino acids concentration (µ mole/Kg fwt) in the phloem tissue of pineapple sweet orange (n = 5).

| Nucleosides | RTa | m/z (+) monitored | EDTA-enhancedexudate | PCAb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cytidine | 4.93 | 244 | 16.3 ± 5.8 | 1.8 ± 0.4 |

| uridine | 8.3 | 245 | 570.1 ± 287.2 | 6.4 ± 4.9 |

| adenosine | 10.76 | 268 | 209.4 ± 122.9 | 1.3 ± 0.8 |

| guanosine | 13.32 | 284 | 723.9 ± 292.6 | 1.4 ± 1.0 |

| L-phenylalanine | 13.02 | 166 | 67.6 ± 18.8 | 6.3 ± 4.3 |

| L-tyrosine | 9.4 | 182 | 61.4 ± 0.0208 | 6.0 ± 3.8 |

| L-tryptophan | 19.83 | 188 | 12.3 ± 4.2 | 1.8 ± 0.6 |

Retention time

Perchloric acid

The nucleotides composition of the phloem sap has been studied in many plant species. Ohshima et al. (1990) found that ATP was the most abundant nucleotide (1.5 mM) in the phloem sap of Zea mays L. followed by ADP (0.82 mM).14 Adenylated nucleotides (ATP, ADP, and AMP) made up about 80% of the total detected nucleotides and the AEC was 0.74.14 GTP (0.32 mM), GDP (0.17 mM), UTP (0.42) and UDP (0.14 mM) were also detected in the phloem sap of Zea mays L.14 Hayashi and Chino (1990) detected ATP (1.76 mM), ADP(0.27 mM), AMP (trace), GTP (0.22 mM), UTP (0.10 mM), and CTP (0.04 mM) in the phloem sap from the uppermost internodes of rice plant and the AEC was 0.93.15

Many of the nucleotides detected in this study were also detected in the juice of pineapple sweet orange; ATP (5-33 ppm) and AMP (5 ppm) were also detected in pineapple sweet orange juice.40-41 Riboflavin (0.022 ppm), FMN (0.054 ppm), FAD (0.17 ppm), NAD (8 ppm) and NADP (1 ppm) were also reported in orange juice.27,43

Although the level of adenylated nucleotides was the higher than other nucleotides (Table 2), the level of uridine and guanosine nucleosides was higher than adenosine (Table 3). The previous result indicated that uridine and guanosine could be present in other forms in citrus phloem sap. In agreement with our results, relatively high levels of UDP-G and GDP-G were detected in plant tissues.44 The presence of high amounts of UDP-G and GDP-G in plants explains the high concentration of these nucleosides in EDTA-enhanced exudate.

ATP and the growth of CLas

The presence of the nucleotides in the phloem sap of citrus plants could be important for both phloem sap feeders and phloem sap limited bacteria such as CLas. These nucleotides could be an important source of energy for CLas. CLas encodes more than one hundred proteins with 92 genes that are involved in active transport, and 40 of these genes are ABC (ATP binding cassette) transport genes.9 Analysis of these ABC transporter related proteins by Li et al. (2012) showed that CLas uses these ABC transporters to import metabolites and enzyme cofactors.45 It is also thought that the presence of this large number of transporter proteins might play an important role in providing CLas with necessary nutrients.9

Besides its ATP synthase CLas also encodes ATP/ADP translocase, which means that CLas can synthesize its own ATP or utilize it directly from its host.23 To test this hypothesis, Vahling et al. (2010) expressed the ATP translocase, nucleotide transport protein (NttA) gene encoded by CLas, in Escherichia coli.46 E. coli harboring the NttA gene was able to import exogenous ATP directly into the cell.46 Vahling et al. (2010) concluded that some intracellular bacteria of plants have the potential to import ATP from their environment.46

Coenzymes and the growth of CLas and ACP

Our results showed that the citrus phloem sap contains NAD, NADP, FMN, and FAD. These nucleotides are important coenzymes and are required by many essential enzymes to function properly. CLas may import these coenzymes and uses them for its own benefit or it may import their precursors that are found in the phloem sap in order to synthesize these coenzymes. Previous studies showed that CLas encodes ninety-two genes that are involved in active transport which can be used to import metabolites and enzyme cofactors.9 In addition, characterization of CLas ATP/ADP translocase showed that it enables CLas bacteria to import ATP from their environment.46 Although the ATP/ADP translocase of CLas was found to be highly specific for ATP and ADP, other nucleotides could also be taken up when present in high concentrations,46 Our results showed that riboflavin, the dietary precursor for FAD and FMN, was found in citrus phloem sap. Many important coenzymes precursors such as folate, thiamine, niacin, riboflavin, and pantothenic acid were reported in orange juice.1 Because these dietary precursors are necessary for the development and survival of aphids, these coenzymes are added to their artificial diets.10

Three aromatic amino acids (phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan) were also detected in the phloem sap of Pineapple sweet orange (Table 3). Separation of these amino acids by reverse phase HPLC-EMS on Atlantis dC18 column is shown in Fig. 1B. These amino acids were also detected in the phloem sap of pineapple orange using GC-MS.22

Phloem sap secondary metabolites

Many limonoids, flavonoids, and hydroxycinnamate were also detected in the phloem sap of sweet oranges (Table 4)

Table 4.

Secondary metabolites concentration (µ mole/Kg fwt) in the phloem tissue (n = 5).

| RTa(min) | “m/z” (+) | λmax(nm) | EDTA-enhancedexudate | PCAb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limonoids | |||||

| nomilin | 48.1 | 515 | —— | 123.9 ± 47.5 | 27.8 ± 20.6 |

| limonin | 46.7 | 471 | —— | 176.6 ± 77.9 | 32.6 ± 13.1 |

| Hydroxycinnamates | |||||

| Hydroxycinnamate (1) | 5.15 | 177, 387 | 326 | 73.3 ± 22.0 | 27.2 ± 4.5 |

| hydroxycinnamate (2) | 5.30 | 177, 387 | 321 | 48.6 ± 10.0 | 44.5 ± 17.7 |

| Hydroxycinnamate (3) | 6.08 | 177, 387 | 326 | 144.2 ± 33.3 | 60.9 ± 8.5 |

| 2'-E-O-feruloylgalactaric acid (16F) | 6.4 | 177, 387 | 326 | 67.2 ± 17.9 | 44.3 ± 10.8 |

| hydroxycinnamate (4) | 6.7 | 177, 387 | 328 | 330.3 ± 85.8 | 165.6 ± 40.0 |

| hydroxycinnamate (5) | 7.4 | 177, 357 | 325 | 71.4 ± 15.8 | 62.2 ± 22.9 |

| hydroxycinnamate (6) | 7.9 | 177, 387 | 329 | 595.8 ± 140.9 | 409.0 ± 90.4 |

| Flavanone glycosides | |||||

| hesperidin | 27.7 | 611 | 283/331 | 462.9 ± 310.2 | 180.8 ± 41.6 |

| Flavone glycosides | |||||

| isorhoifolin | 27.1 | 579 | 267/338 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| diosmin | 28.2 | 609 | 253/267/347 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 5.4 ± 1.2 |

| vicenin-2 | 7.5 | 595 | 271/337 | 21.8 ± 4.8 | 24.2 ± 8.8 |

| Methoxylated flavones | |||||

| isosinensetin | 24.5 | 373 | 249/270/342 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.3 |

| sinensetin | 26.1 | 373 | 243/264/333 | 9.3 ± 2.2 | 12.4 ± 3.5 |

| nobiletin | 28.0 | 403 | 249/270/334 | 7.0 ± 1.9 | 10.3 ± 3.5 |

| tetramethylscutellarein | 28.3 | 343 | 266/323 | 3.4 ± 1.2 | 4.7 ± 1.4 |

| heptamethoxyflavone | 29.2 | 433 | 253/268/343 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| 5-desmethylsinensetin | 29.7 | 359 | 249/275/342 | 3.2 ± 1.2 | 3.6 ± 1.3 |

| tangeretin | 30.2 | 373 | 271/321 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

| 5-desmethylnobiletin | 31.6 | 389 | 253/282/343 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.5 |

Retention time

Perchloric acid

Limonoids

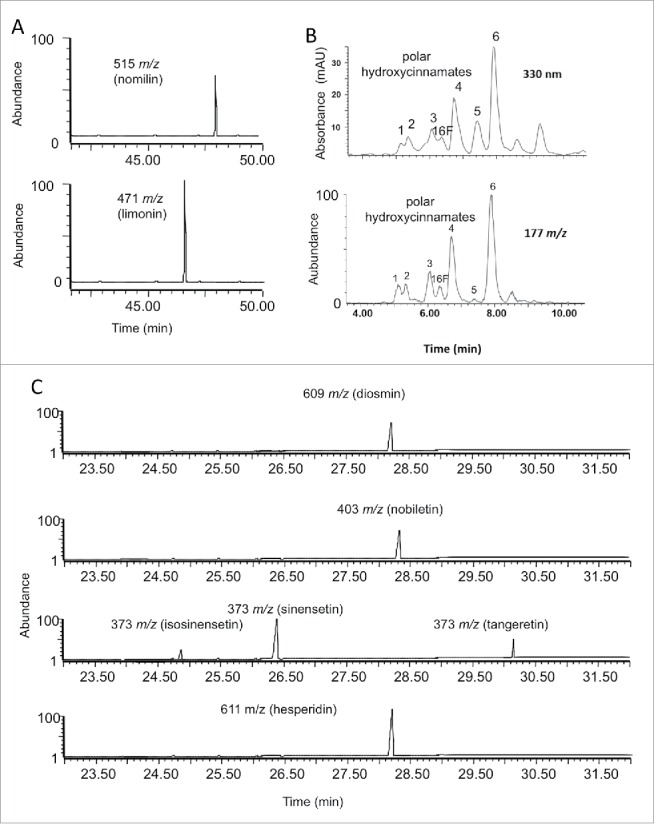

Two limonoids were detected in the phloem sap (Fig. 2A); nomilin (124 µ mole/kg fwt) and limonin (177 µ mole/kg fwt). Our results showed that limonoids were found at relatively high amounts in the phloem sap. This finding is not surprising because limonoids, mainly nomilin, are biosynthesized from acetate in the stems and then translocated to other locations such as leaves, fruit, and seeds. Nomilin is the direct precursor of obacunone which then is used to make limonin.47 Limonoids were extensively investigated in citrus juice because they are responsible for bitterness of citrus juice.48 The concentration of limonin and nomilin in navel orange juice ranges from 3–8 and 0.3 to 3 ppm, respectively.48

Figure 2.

Positive ESI-MS Single Ion Monitoring (SIM) chromatograms of limonoides including nomilin and limonin (A) and polar hydroxycinnamates (B), and main flavonoides (C) detected in citrus phloem. Compounds with 177 m/z fragment ions (B bottom) are associated with ferulic acid conjugates, and the UV spectra (B top) of these compounds corroborate this association.

Hydroxycinnamates

Seven hydroxycinnamates including six unknowns were also detected in the phloem sap of pineapple sweet orange trees (Fig. 2B). These compounds shared similar UV spectra, as well as mass spectra similar to the known standard, 2-(E)-O-feruloylgalactaric acid.49 The shared 177 m/z ions are indicative of fragment ions of ferulic acid (FA) (FA-H2O+H)+ and the 387 m/z ions occur from the ionized molecular ions (FA GalA+H)+ or (FA GluA+H)+. The concentration of these hydroxycinnamates ranged from 67 to 596 µ mole/kg fwt (Table 4). Feruloyl-derivatives of galactaric and glucaric (aldaric) acids were also reported in sweet orange peels and sweet orange leaves.49-51 Surprisingly, the concentrations of these hydroxycinnamates were higher in leaves from ‘Hamlin’ and ‘Valencia’ sweet orange trees in response to CLas infection.51 The increase in HCAs in CLas-infected plants indicated that these compounds may play a role in citrus-CLas interactions.51

Flavonoids

One flavanone glycoside (hesperidin) was detected in the pineapple orange tree phloem sap (Fig. 2C). Hesperidin (463 µ mole/kg fwt) was the most predominant flavonoid (Table 4). Hesperidin was the most abundant flavonoid in leaves of sweet orange trees.51-52 Hesperidin was also found at high concentrations (168-380 ppm) in citrus juice.53 Three flavone glycosides (isorhoifolin, diosmin, and vicenin-2) were also detected in the citrus phloem sap. Vicenin-2 concentration was relatively higher than isorhoifolin and diosmin (Table 4). Diosmin and isorhoifolin were also reported in citrus leaves and juice.51,52,54

Eight methoxylated flavones were also detected in the phloem sap (Table 4), however they were found at concentrations below 12 µ mole/kg fwt (Table 4). Sinensetin was the most predominant flavone followed by nobiletin (Table 4). Isosinensetin, sinensetin, nobiletin, tetramethylscutellarein, heptamethoxyflavone, and tangeretin were previously reported in sweet orange leaves and juice.51-52 Our current and previous study showed that many of the components found in the citrus phloem sap, were also found in the orange juice.22 The presence of these components in orange juice could explain the prolonged viability of CLas after the addition of orange juice to growth medium.55

Recently, it was suggested that flavonoids are transported within plant.20,56 Flavonoids are not produced in roots grown in complete darkness because expression of genes encoding enzymes of flavonoids biosynthesis is dependent on light.56 The presence of flavonoids in root tips of plant grown in light-shield roots suggested that flavonoids are transported from shoot to root.56 Using fluorescence microscopy, Buer et al. (2007) showed that external flavonoids applied to Arabidopsis flavonoid mutants (cannot make flavonoids) accumulates in tissues distal to the application site.20 In a recent study, many flavonoids were also detected in the phloem sap of banana trees.57

Flavonoids are implicated in many important functions in plant including signaling to symbiotic bacteria and they may play an important role in plant resistance against pathogenic bacteria and fungi.58 Flavonoids may enhance plant resistance to pathogens in several different ways: (1) by quenching the reactive oxygen species which form in plants after infection, (2) by inhibition of pathogen's digestive enzymes as a result of chelating metals required for their activity, (3) by induction of the hypersensitivity reaction and programmed cell death, (4) and by tightening of the plant cell structure by altering indole-3-acetic acid activity.59 In addition, flavonoids, can stimulate or inhibit insect feeding and oviposition.21 Although the scientific literature indicates that flavonoids may play a role in plant interaction with insect and plant pathogens, no information is available about their potential role in citrus interaction with ACP and CLas.

Conclusion

In this study, we investigated the micro- and macro-nutrients, nucleotides, and secondary metabolites in the phloem sap of sweet orange. The results of this study will improve our knowledge about the nature and the composition of citrus phloem sap and reveal more information about the available nutrients for CLas and ACP.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank our lab members for critical reading of the manuscript. This study was supported with grant #100264 for NK received from Citrus Research and Development Foundation (CRDF).

Authors contribution

Conceived and designed the experiments: NK, FH, JM Performed the experiments: FH, JM, VM Analyzed the data: NK, FH, JM, VM. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: NK, JM. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: NK, FH, JM, VM.

References

- 1.Liu Y, Heying E, Tanumihardjo SA. History, global distribution, and nutritional importance of citrus fruits. Comprehensive Rev Food Sci Food Safety 2012; 11(6):530-45; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2012.00201.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halbert SE, Manjunath KL. Asian citrus psyllids (Sternorrhyncha: Psyllidae) greening disease of citrus: a literature review and assessment of risk in Florida. Fla Entomol 2004; 87:330-53; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1653/0015-4040(2004)087%5b0330:ACPSPA%5d2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batool A, Iftikhar Y, Mughal SM, Khan MM, Abbas M, Khan IA. Citrus greening disease – A major cause of citrus decline in the world: A review. J Hort Sci 2004; 34:159-66 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassanezi RB, Montesino LH, Stuchi ES. Effects of huanglongbing on fruit quality of sweet orange cultivars in Brazil. Eur J Plant Pathol 2009; 125:565-72; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10658-009-9506-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottwald TR. Current epidemiological understanding of citrus huanglongbing. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2010; 48:119-39; PMID:20415578; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slisz AM, Breksa APIII, Mishchuk DO, McCollum G, Slupsky CM. Metabolomic analysis of citrus infection by ‘Candidatus Liberibacter’ reveals insight into pathogenicity. J Proteome Res 2012; 11:4223-30; PMID:22698301; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/pr300350x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-desouky A, Hall D. Replication of Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus in its psyllid vector Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera: Liviidae) following various acquisition access periods. Conference Paper. February 2015. International Research Conference on Huanglongbing, At Orlando, Fl, USA; PMID:22698301 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bové JM, Garnier M. Phloem- and xylem-restricted plant pathogenic bacteria. Plant Sci 2002; 163:1083-98; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0168-9452(02)00276-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang N, Trivedi P. Citrus Huanglongbing: A Newly Relevant Disease Presents Unprecedented Challenges. Phytopathology 2013; 103:652-65; PMID:23441969; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1094/PHYTO-12-12-0331-RVW [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trébicki P, Harding RM, Powel KS. Anti-metabolic effects of Galanthus nivalis agglutinin and wheat germ agglutinin on nymphal stages of the common brown leafhopper using a novel artificial diet system. Entomol Exp Appl 2009; 131:99-105; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2009.00831.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dinant S, Bonnemain JL, Girousse C, Kehr J. Phloem sap intricacy and interplay with aphid feeding. C R Biol 2010; 333:504-15; PMID:20541162; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.crvi.2010.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashi H, Chino M. Collection of pure phloem sap from wheat and its chemical composition. Plant Cell Physiol 1986; 27:1387-93 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deeken R, Geiger D, Fromm J, Koroleva O, Ache P, Langenfeld-Heyser R, Sauer N, May ST, Hedrich R. Loss of the AKT2/3 potassium channel affects sugar loading into the phloem of Arabidopsis. Planta 2002; 216:334-44; PMID:12447548; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00425-002-0895-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oshima T, Hayashi H, Chino M. Collection and chemical composition of pure phloem sap from Zea mays L. Plant Cell Physiol 1990; 31:735-37 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi H, Chino M. Chemical composition of phloem sap from the uppermost internode of the rice plant. Plant Cell Physiol 1990; 31:247-51 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoad GV. Transport of hormones in the phloem of higher plants. Plant Growth Regul 1995; 16:173-82; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF00029538 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heil M, Ton J. Long-distance signaling in plant defense. Trends Plant Sci 2008; 13:264-72; PMID:18487073; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madey M, Nowack L, Thompson J. Isolation and characterization of lipid in phloem sap of canola. Planta 2002; 214:625-34; PMID:11925046; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s004250100649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehrer A, Dugassa-Gobena D, Vidal S, Seifert K. Transport of resistance-inducing sterols in phloem sap of barley. Z Naturforsch C 2000; 55:948-52; PMID:11204200; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1515/znc-2000-11-1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buer CS, Muday GK, Djordjevic MA. Flavonoids are differentially taken up and transported long distances in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2007; 145:478-90; PMID:17720762; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1104/pp.107.101824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simmonds MSJ. Importance of favonoids in insect-plant interactions: feeding and oviposition. Phytochemistry 2001; 56:245-52; PMID:11243451; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00453-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hijaz F, Killiny N. Collection and chemical composition of phloem sap from citrus sinensis L. Osbeck (Sweet Orange). PLoS One 2014; 9(7):e101830; PMID:25014027; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0101830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duan Y, Zhou L, Hall DG, Li W, Doddapaneni H, Lin H, Liu L, Vahling CM, Gabriel DW, Williams KP, et al.. Complete genome sequence of citrus Huanglongbing bacterium, ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus’ obtained through metagenomics. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact 2009; 22:1011-20; PMID:19589076; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1094/MPMI-22-8-1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasegawa S, Bennet RD, Verdon CP. Limonoids in citrus seeds: Origin and relative concentration. J Agric Food Chem 1980; 28:922-25; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/jf60231a016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horowitz RM, Gentili B. Flavonoid Constituents in Citrus, in Citrus Science and Technology 1977; Vol 1, Nagy S, Shaw PE, Veldhuis MK (Eds.) Avi Publishing Co; Westport, CN [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klawitter J, Schmitz V, Klawitter J, Leibfritz D, Christians U. Development and validation of an assay for the quantification of 11 nucleotides using LC/LC-electrospray ionization-MS. Anal Biochem 2007; 365:230-9; PMID:17475198; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ab.2007.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrés -Lacueva C, Mattivi F, Tonon D. Determination of riboflavin, flavin mononucleotide and flavin-adenine dinucleotide in wine and other beverages by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection. J Chrom A 1998; 823:355-63; PMID:9818412; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0021-9673(98)00585-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deotale RD. Macro and micro nutrient deficiency symptoms in Nagpur orange (Citrus reticulata Blanco). J Soils Crops 2005; 15:284-6 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knoblauch M, Peters WS, Ehlers K, van Bel AJE. Reversible calcium-regulated stopcocks in legume sieve tubes. Plant Cell 2001; 13:1221-30; PMID:11340193; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1105/tpc.13.5.1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Furch ACU, Hafke JB, Schulz A, van Bel AJE. Ca2+-mediated remote control of reversible sieve tube occlusion in Vicia faba. J Exp. Bot 2007; 58:2827-38; PMID:17615409; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jxb/erm143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merchant A, Peuke AD, Keitel C, Macfarlane C, Warren CR, Adams MA. Phloem sap and leaf δ13C, carbohydrates, and amino acid concentrations in Eucalyptus globulus change systematically according to flooding and water deficit treatment. J Exp Bot 2010; 61:1785-93; PMID:20211969; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jxb/erq045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pate J, Arthur D. δ13C analysis of phloem sap carbon: novel means of evaluating seasonal water stress and interpreting carbon isotope signatures of foliage and trunk wood of Eucalyptus globulus. Oecologia 1998; 117:301-11; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s004420050663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peuke AD, Rokitta M, Zimmermann U, Schreiber L, Haase A. Simultaneous measurement of water flow velocity and solute transport in xylem and phloem of adult plants of Ricinus communis over a daily time course by nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometry. Plant Cell Environment 2001; 24:491-503; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00704.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lohaus G, Hussmann M, Pennewiss K, Schneider H, Zhu JJ, Sattelmacher B. Solute balance of a maize (Zea mays L.) source leaf as affected by salt treatment with special emphasis on phloem retranslocation and ion leaching. J Exp Bot 2000; 51:1721-32; PMID:11053462; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jexbot/51.351.1721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bao SX, Wang ZH, Liu JS. X-ray fluorescence analysis of trace elements in fruit juice. Spectrochimica Acta Part B–Atomic Spectroscopy 1999; 54:1893-7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0584-8547(99)00160-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dadd RH. Improvement of synthetic diet for aphid Myzus persicae using plant juices nucleic acids or trace metals. J Insect Physiol 1967; 13:763-78; PMID:6046968; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0022-1910(67)90125-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Telagamsetty S, Nelson SD, Simpson C, Setamou M. Impact of Young Citrus Shoot Flush Nutrients and Phloem Sap Composition on Asian Citrus Psyllid Populations Poster presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting Of Am Society Horticultural Sci. New Orleans, LA [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao H, Sun R, Albrecht U, Padmanabhan C, Wang A, Coffey MD, Girke T, Wang Z, Close TJ, Roose M, et al.. Small RNA profiling reveals phosphorus deficiency as a contributing factor in symptom expression for citrus huanglongbing disease. Mol Plant 2013; 6:301-10; PMID:23292880; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/mp/sst002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vahling-Armstrong CM, Zhou H, Benyon L, Morgan JK, Duan Y. Two plant bacteria, S. meliloti and Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus, share functional znuABC homologues that encode for a high affinity zinc uptake system. PLoS One 2012; 7(5):e37340; PMID:22655039; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0037340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barmore CR, Biggs RH. Acid-soluble nucleotides of juice vesicles of citrus fruit. J Food Sci 1972; 37:712-4; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1972.tb02732.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buslig BS, Attaway JA. A study of acidity levels and adenosine triphosphate concentration in various citrus fruits. Florida State Hort Soc Proc 1969; 82:206-8 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruemmer J. Redox state of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides in citrus fruits. J Agric Food Chem 1969; 17:1313-5; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/jf60166a023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nieman RH, Clark RA. Measurement of plant nucleotides by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chrom A 1984; 317:271-81; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)91666-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li W, Cong Q, Pei J, Kinch LN, Grishin NV. The ABC transporters in ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus’. Proteins 2012; 80:2614-8; PMID:22807026; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/prot.24147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vahling CM, Duan Y, Lin H. Characterization of an ATP translocase identified in the destructive plant pathogen “Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus.” J Bacteriol 2010; 192:834-40; PMID:19948801; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JB.01279-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ou P, Hasegawa S, Herman Z, Fong CH. Limonoid biosynthesis in the stem of Citrus limon. Phytochemistry 1988; 27:115-8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0031-9422(88)80600-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raithore S, Dea S, McCollum G, Manthey JA, Bai J, Leclair C, Hijaz F, Narciso JA, Baldwin EA, Plotto A. Development of delayed bitterness and effect of harvest date in stored juice from two complex citrus hybrids. J Sci Food Agric 2015; 96:422-429; PMID:25615579; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jsfa.7105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Risch B, Herrmann K, Wray V. (E)-O-p-coumaroyl-, (E)-O-feruloyl-derivatives of glucaric acid in citrus. Phytochemistry 1988; 27:3327-29; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0031-9422(88)80059-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Risch B, Herrmann K, Wray V. Grotjahn, L. Two′-(E)-O-paracoumaroylgalactaric acid and 2′-(E)-O-feruloylgalactaric acid in citrus. Phytochemistry 1987; 26:509-10; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)81444-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hijaz FM, Manthey JA, Folimonova SY, Davis CL, Jones SE, Reyes-De-Corcuera JI. An HPLC-MS characterization of the changes in sweet orange leaf metabolite profile following infection by the bacterial pathogen candidatus liberibacter asiaticus. PLoS One 2013; 8(11):e79485; PMID:24223954; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0079485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawaii S, Tomono Y, Katase E, Ogawa K, Yano M, Koizumi M, Ito C, Furukawa H. Quantitative study of flavonoids in leaves of citrus plants. J Agric Food Chem 2000; 48:3865-71; PMID:10995283; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/jf000100o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vallejo F, Larrosa M, Escudero E, Zafrilla MP, Cerdá B, Boza J, García-Conesa MT, Espín JC, Tomás-Barberán FA. Concentration and solubility of flavonones in orange beverages affect their bioavailability in humans. J Agric Food Chem 2010; 58:6516-24; PMID:20441150; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/jf100752j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gattuso G, Barreca D, Gargiulli C, Leuzzi U, Caristi C. Flavonoid composition of citrus juices: review. Molecules 2007; 12:1641-73; PMID:17960080; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3390/12081641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parker JK, Wisotsky SR, Johnson EG, Hijaz FM, Killiny N, Hilf ME, De La Fuente L. Viability of ‘Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus’ prolonged by addition of citrus juice to culture medium. Phytopathol 2014; 104:15-26; PMID:23883155; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1094/PHYTO-05-13-0119-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petrussa E, Braidot E, Zancani M, Peresson C, Bertolini A, Sonia Patui S, Vianello A. Plant flavonoids—biosynthesis, transport and involvement in stress responses. Int J Mol Sci 2013; 14:14950-73; PMID:23867610; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3390/ijms140714950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pothavorn P, Kitdamrongsont K, Swangpol S, Wongniam S, Atawongsa K, Savasti J, Somana J. Sap Phytochemical Compositions of Some Bananas in Thailand. J Agric Food Chem 2010; 58:8782-7; PMID:20681667; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/jf101220k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Redmond JW, Batley M, Djordjevic MA, Innes RW, Kuempel PL, Rolfe BG. Flavones induce expression of nodulation genes in Rhizobium. Nature 1986; 323:632-5; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/323632a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mierziak J, Kostyn K, Kulma A. Flavonoids as important molecules of plant interactions with the environment. Molecules 2014; 19:16240-65; PMID:25310150; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3390/molecules191016240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]