Abstract

Background:

NH125, a known WalK inhibitor kills MRSA persisters. However, its precise mode of action is still unknown.

Methods & results:

The mode of action of NH125 was investigated by comparing its spectrum of antimicrobial activity and its effects on membrane permeability and giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) with walrycin B, a WalR inhibitor and benzyldimethylhexadecylammonium chloride (16-BAC), a cationic surfactant. NH125 killed persister cells of a variety of Staphylococcus aureus strains. Similar to 16-BAC, NH125 killed MRSA persisters by inducing rapid membrane permeabilization and caused the rupture of GUVs, whereas walrycin B did not kill MRSA persisters or induce membrane permeabilization and did not affect GUVs.

Conclusion:

NH125 kills MRSA persisters by interacting with and disrupting membranes in a detergent-like manner.

Keywords: : antibiotics, giant unilamellar vesicle, MRSA, NH125, two-component system

Staphylococcus aureus is a Gram-positive human pathogen that colonizes about a third of healthy humans [1–3] and causes a wide range of infections from minor skin colonization to life-threatening infections such as toxic shock syndrome [3–6]. Antibiotic-resistant S. aureus, such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), is prevalent both in hospitals and in the community [4–6]. In the USA, MRSA causes approximately 19,000 deaths and accrues about $3–4 billion of healthcare costs per year [7]. In addition to its ability to acquire antibiotic-resistance, S. aureus readily forms persisters, which are nongrowing dormant cells that exhibit a high level of tolerance to most conventional antibiotics [8–11]. Recent studies have shown that persisters are responsible for the recalcitrance of chronic infections to antibiotic therapy [12,13]. Vancomycin is currently used as the drug of last resort for S. aureus, but vancomycin-intermediate or -resistant strains are arising [14] and this agent is not effective against MRSA persisters [11]. Therefore, new antibiotics against both antibiotic-resistant and -tolerant S. aureus are urgently needed.

Two component signal transduction systems (TCS) are major tools that enable bacteria to sense, respond and adapt to environmental changes [15,16]. Generally, TCS consist of a sensor histidine kinase (HK), which is autophosphorylated upon sensing environmental stimuli and a response regulator (RR), which is phosphorylated by its cognate sensor kinase and subsequently modulates the transcription of specific genes [15]. TCS are involved in many cellular processes in bacteria, such as sporulation, virulence, biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance [15]. Also, some TCS such as WalK/R (also known as YycF/G) and YhcS/R (also known as AirS/R) in S. aureus are essential for bacterial survival [17,18]. Essential TCS are considered to be promising targets for the development of antibiotics due to their indispensability for bacterial survival and their absence in mammalian cells [16]. In particular, the WalK/R system, which is highly conserved in low GC content Gram-positive pathogens such as S. aureus, Streptococcus pneumonia and Enterococcus faecalis, has been exploited as a target for developing new antibiotics [19–26]. Indeed, the WalK inhibitors NH125 [19,20], signermycin B [25], walkmycin B [22] and waldiomycin [26], as well as the WalR inhibitors walrycin A [23] and walrycin B [23], have been shown to have antimicrobial activity against S. aureus or MRSA.

As previously reported, we developed a fluorescence-based screening strategy for identifying antimicrobial agents against MRSA persisters and found that the WalK inhibitor NH125 killed MRSA persisters by inducing rapid membrane permeabilization [11]. In this paper, we elucidate the mode of action by which NH125 kills MRSA persisters by comparing the activity of NH125 with a functional analog, the WalR inhibitor walrycin B and a well-characterized structural analog, benzyldimethylhexadecylammonium chloride (16-BAC), a cationic surfactant. In order to determine whether the mechanism by which NH125 kills MRSA persisters is similar to walrycin B or 16-BAC, we tested the spectrum of antibiotic activity of these compounds and their effects on MRSA persister membrane permeability. We also studied the effects of these compounds on the stability of giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs), a system for modeling the cell membrane [27,28]. Our results show NH125 kills MRSA persisters similarly to 16-BAC, by directly interacting with and disrupting membranes and not by inhibiting the activity of the WalK/R system.

Materials & methods

Bacterial strains, growth conditions & persister isolation

Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strain MW2 BAA-1707 [29], Enterococcus faecium E007 [30,31], Klebsiella pneumoniae WGLW2 (BEI Resources, Manassas, VA, USA), Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 17978 [32], Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 [33], Enterobacter aerogenes ATCC 13048 and 11 clinical S. aureus isolates [34] were used to test antimicrobial activity. All bacterial strains were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) (BD, NJ, USA) at 37°C. Similarly to others [8–10], we previously found that essentially 100% of stationary-phase S. aureus MW2 cells become persisters, which are tolerant to conventional antibiotics such as gentamicin, ciprofloxacin and vancomycin [11]. Thus, S. aureus MW2 persisters were prepared by growing 25 ml of an S. aureus MW2 culture overnight to stationary phase at 37°C at 225 rpm [11].

Antimicrobial agents & chemicals

Vancomycin, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, NH125 and benzyldimethylhexadecylammonium chloride (16-BAC) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA) and walrycin B was purchased from MedChem Express (NJ, USA), while 10 mg/ml stocks of all antibiotics were made in DMSO or ddH2O.

Persister membrane permeability assay

Black, clear-bottom 96-well plates (Corning no. 3904) were filled with 50 μl of phosphate buffered saline (PBS)/well containing the indicated concentration of antibiotics. Stationary bacteria were then washed three times with the same volume of PBS. The washed cells were diluted to OD600 = 0.4 (˜108 CFU/ml) with PBS. SYTOX Green (Molecular Probes) was added to 10 ml of the diluted persister suspension to a final concentration of 5 μM and incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. A 50 µl of the persister/SYTOX Green mixture was added to each well of 96-well plates containing antibiotics and fluorescence was measured at room temperature using a spectrophotometer (SpectraMax M2, Molecular Devices) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 nm and 525 nm, respectively. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Time course assay

In order to correlate decreases in bacterial cell viability with membrane permeability, the same initial concentration as used in the membrane permeability assay was used for the time course killing assay. Overnight cultures of persisters were washed three times with PBS and diluted to OD600 = 0.2 (5 × 107–108 CFU/ml) with the same buffer; 1 ml of the persister suspension containing the indicated concentrations of antibiotics was added to the wells of a 2 ml deep well assay block (Corning Costar 3960) and incubated at 37°C, with shaking at 225 rpm. At specific times, 50-μl samples were removed, serially diluted and spot-plated on tryptic soy agar (TSA, BD) plates to enumerate the number of persister cells. These experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Minimum inhibitory concentration assay

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MICs) of antibiotics were determined by the standard microdilution method [35]. Briefly, bacterial overnight cultures were diluted to approximately 1 × 105 CFU/ml in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton (CaMH) broth; 50 µl of the diluted cultures were added to each well of a 96-well plate containing 50 µl serial twofold dilutions of antibiotic compounds in CaMH broth. The 96-well plate was incubated at 37°C for 18 h and bacterial growth was evaluated by measuring the optical density (OD) at 600 nm using a spectrophotometer (SpectraMax M2, Molecular Devices). Bacterial growth was defined as OD600nm ≥ 0.1. Assays were conducted in triplicate.

Preparation of GUVs & observation of effects of compounds on GUVs

Dioleoyl-glycero-phosphocholine (DOPC), Dipalmitoyl-glycero-phosphoglycerol (DOPG) and Dioleoyl-glycero-phosphoethanolamine-N-lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl (18:1 Liss Rhod PE) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). GUVs were prepared by slightly modifying the electroformation method described in previous studies [36–38]. DOPC/DOPG/18:1 Liss Rhod PE (7:3:0.005) were dissolved in chloroform at a total lipid concentration of 4 mM. 40 µl of the lipid solution was spread onto two indium tin oxide (ITO)-coated slides (50 × 75 × 1.1 mm, Delta Technologies, Loveland, CO, USA) and dried under low pressure for 2 h to remove the organic solvents. An electroformation chamber was assembled by inserting a 2-mm thick Teflon spacer between the two ITO slides. The chamber was then filled with 2 ml of 100 mM sucrose and sealed with binder clips. The swelling of the lipid bilayers was controlled using an electric AC-field (10 Hz) first by increasing the field-strength from 0 to 0.5 kV/m for 30 min and then keeping it constant for another 30 min. To enhance the detachment of the GUV from the glass surfaces, the frequency was reduced to 5 Hz for 20 min. The vesicle suspension was diluted (1:8) in a 110 mM glucose solution to obtain a slightly larger density inside the GUVs than outside. A 45 µl of the diluted vesicle suspension (˜500 vesicles) was transferred to a black, clear-bottom 384-well plate (Corning no. 3712). To allow all the vesicles to settle down to the bottom of the well, the plate was left in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. After adding 5 µl of a 100X MIC compound to a well (final compound concentration: 10X MIC), the GUVs were observed and recorded by an optical microscope equipped with fluorescence contrast and a digital camera (40× or 63× objectives, Axio Observer. A1 & AxioCam MRm, Zeiss, Germany). Images and videos are representative of three independent experiments.

Human blood hemolysis

Hemolytic activity of compounds on human erythrocytes (Rockland Immunochemicals, PA, USA) was evaluated by slightly modifying a previously described method [34]. Briefly, 100 µl of 4% human erythrocytes suspended in PBS was added to 100 µl of twofold serial dilutions of compounds in PBS, 0.2% DMSO (negative control), or 2% Triton-X 100 (positive control) in a 96-well plate. The 96-well plate was incubated at 37°C for 1 h and then, centrifuged at 500 g for 5 min; 100 µl of the supernatant was transferred to a fresh 96-well plate and absorbance of supernatants was measured at 540 nm. Percent hemolysis was calculated using the following equation: (A540nm of compound treated sample − A540nm of 0.1% DMSO treated sample)/(A540nm of 1% Triton X-100 treated sample − A540nm of 0.1% DMSO treated sample) × 100. HC50 (concentration of a compound causing 50% hemolysis) was determined using SigmaPlot 10.0 (Systat Software Inc.).

Results

NH125 eradicates persisters of 11 clinical S. aureus isolates

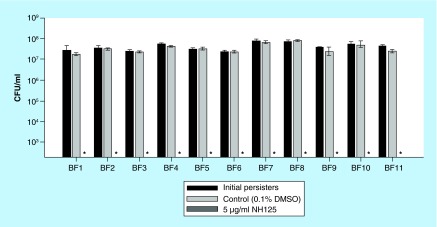

In a previous study, we found that NH125 eradicated persisters formed by a reference MRSA strain MW2 at 5 µg/ml, which was nontoxic to Caenorhabditis elegans, a model nematode for assessing toxicity [11]. To evaluate the potential of NH125 for clinical applications, we tested whether NH125 can kill growing and persister cells of 11 clinical S. aureus isolates [34]. The 11 isolates consisted of 9 MRSA strains, BF1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10 and 2 methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) strains, BF6 and 9 (Table 1). Whereas growing cells of all 11 isolates were susceptible to conventional antibiotics including gentamicin, ciprofloxacin and vancomycin (Table 1), their stationary-phase cells showed tolerance to 10X MICs of all three antibiotics (Supplementary Figure 1). This result indicates that the antibiotic tolerance of stationary phase cells appears to be a consistent feature of S. aureus strains, regardless of their sensitivity to methicillin. MICs of NH125 against the 11 clinical isolates were 2–4 µg/ml (Table 1). However, in contrast to gentamicin, ciprofloxacin and vancomycin, 5 µg/ml of NH125 eradicated approximately 5 × 107–108 CFU/ml persister cells of all of the clinical isolates to the limit of detection within 4 h (Figure 1). These results demonstrate that NH125 can not only block the growth of a broad spectrum of S. aureus strains under standard MIC conditions, but also kill persistent cells at a concentration that is nontoxic to human red blood cells (as described below in Figure 2).

Table 1. . Minimum inhibitory concentration against 11 clinical staphylococcal isolates.

| Strains | Oxacillin (µg/ml) | NH125 (µg/ml) | Gentamicin (µg/ml) | Ciprofloxacin (µg/ml) | Vancomycin (µg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BF1 |

>64 |

4 |

1 |

0.5 |

1 |

| BF2 |

>64 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| BF3 |

32 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| BF4 |

16 |

2 |

1 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

| BF5 |

>64 |

2 |

1 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

| BF6 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

| BF7 |

>64 |

2 |

1 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

| BF8 |

>64 |

2 |

1 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

| BF9 |

0.25 |

2 |

1 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

| BF10 |

>64 |

2 |

1 |

0.25 |

0.5 |

| BF11 | >64 | 2 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 |

Figure 1. . NH125 eradicates persisters formed by 11 clinical staphylococcal isolates.

Persister cells of 11 clinical staphylococcal isolates were treated with 0.1% DMSO (control) and 5 µg/ml NH125 for 4 h. Persister viability was measured by serial dilution and plating on TSA plates. The asterisks on the x-axis are below the level of detection (2 × 102 CFU/ml). Results are shown as means ± SD; n = 3.

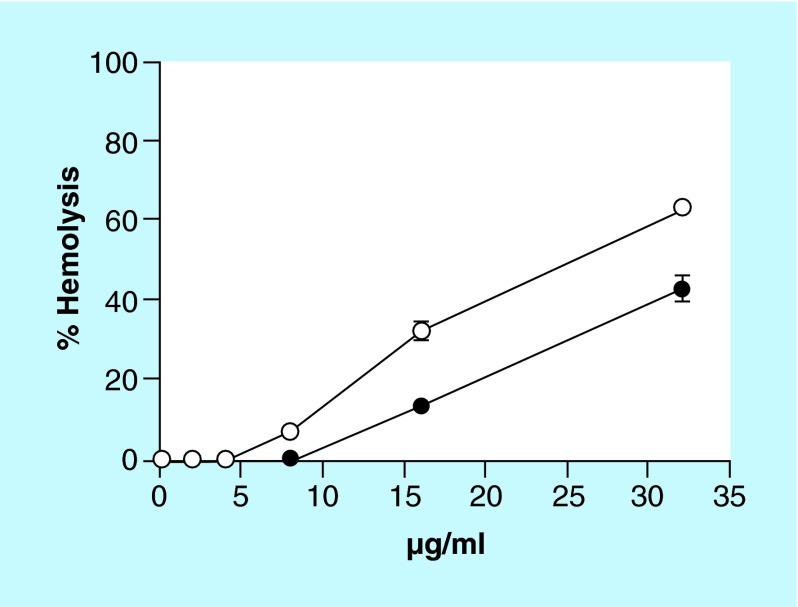

Figure 2. . NH125 shows less hemolytic activity against human erythrocytes compared with 16-BAC.

1% human erythrocytes were treated with twofold serially diluted concentration of NH125 (solid circles) or 16-BAC (open circles) for 1 h at 37°C. A sample treated with 1% Triton-X 100 was used as the control for 100% hemolysis. Results are shown as means ± SD; n = 3.

NH125 shows antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive & Gram-negative bacteria

The WalK/R system is specifically found in low GC content Gram-positive bacteria [17,39]. We hypothesized that if NH125 kills MRSA solely by inhibiting the WalK/R system, NH125 should not show activity against Gram-negative bacteria. We, therefore, determined the antimicrobial activity of NH125 against four Gram-negative species, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa and E. aerogenes in comparison to two low GC content Gram-positive species, E. faecium and S. aureus. These six bacterial species are known as the ESKAPE pathogens, which are responsible for the majority of nosocomial infections and have an ability to ‘escape’ antibiotic treatment [40].

Since WalR can be phosphorylated by other kinases or small molecule phosphate donors despite inhibition of WalK [41,42], WalR inhibitors are more effective than WalK inhibitors in blocking the regulatory cascades governed by the WalK/R system [23]. Thus, walrycin B, a WalR inhibitor (Figure 3B) was chosen as a functional analog of NH125 for testing its WalK/R inhibitory activity. Consistent with a previous study [23], walrycin B demonstrated antimicrobial activity against the Gram-positive bacteria E. faecium (MIC 2 µg/ml) and S. aureus (MIC 4 µg/ml) (Table 2), but not against the four Gram-negative bacterial species tested. In contrast, NH125 showed activity against both the Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, although NH125 exhibited better antimicrobial activity against the Gram-positive (MIC 1–2 µg/ml) than the Gram-negative bacteria (MIC of 8–16 μg/ml for all four species) (Table 2). These results suggest that NH125 may have other targets in addition to the WalK/R system.

Figure 3. . Chemical structure of compounds.

(A) NH125, (B) Walrycin B and (C) 16-BAC.

Table 2. . Minimum inhibitory concentration against ESKAPE pathogens.

| Strains | NH125 (µg/ml) | 16-BAC (µg/ml) | Walrycin B (µg/ml) | Gentamicin (µg/ml) | Ciprofloxacin (µg/ml) | Vancomycin (µg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. faecium E007 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

>64 |

>64 |

1 |

|

S. aureus MW2 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

1 |

0.5 |

1 |

|

K. pneumonia WGLW2 |

8 |

16 |

>64 |

1 |

0.063 |

>64 |

|

A. baumannii ATCC 17978 |

16 |

8 |

>64 |

1 |

0.25 |

>64 |

|

P. aeruginosa PA14 |

16 |

64 |

>64 |

2 |

0.063 |

>64 |

| E. aerogenes ATCC 13048 | 16 | 16 | >64 | 2 | 0.031 | >64 |

To explore another potential mode of action for NH125, we also compared the antimicrobial activity of NH125 to benzyldimethylhexadecylammonium chloride (16-BAC), an NH125 structural analog consisting of a cationic head and a C16 alkyl chain (Figure 3C). 16-BAC is a cationic detergent and is known to kill bacteria by directly disrupting membranes [43,44]. As shown in Table 2, similarly to NH125, 16-BAC demonstrated antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive (MIC 1–2 µg/ml) and Gram-negative bacteria (MIC 8–64 µg/ml). These results suggest that NH125 may directly disrupt bacterial membranes, similar to its structural analog 16-BAC.

The bactericidal activity of NH125 on MRSA persisters is not mediated by the inhibition of the WalK/R system.

As we previously reported [11], MRSA MW2 persisters exhibit a high level of tolerance to 10X MIC of conventional antibiotics, but are rapidly killed by NH125. Similarly to NH125, 10X MIC 16-BAC (20 µg/ml) induced rapid membrane permeabilization and completely killed approximately 108 CFU/ml MRSA persisters to the limit of detection (2 × 102 CFU/ml) within 15 min (Figure 4A & B). In contrast, the DMSO control or walrycin B at 10X MIC (40 µg/ml) did not kill MRSA persisters or induce membrane permeabilization (Figure 4C & D). Moreover, unlike NH125 and 16-BAC, walrycin B did not induce membrane permeabilization up to 64 µg/ml (Supplementary Figure 2). This result indicates that the inhibition of WalK may not play an important role in inducing membrane permeabilization. To further examine the effects of the WalK inhibition on membrane permeabilization, we treated growing MRSA cells with 10X MIC walrycin B, NH125 and 16-BAC. Consistent with the results of persistent MRSA cells (Figure 4), NH125 and 16-BAC caused rapid membrane permeabilization whereas walrycin B did not permeabilize the growing MRSA cell membranes (Supplementary Figure 3). These results demonstrate that both NH125 and 16-BAC kill persisters by a common mechanism involving direct disruption of persister cell membranes, which is independent of the WalK/R system. Also, antibiotic activity of NH125 against growing MRSA may be achieved by multiple mechanisms including membrane permeabilization, in addition to the inhibition of WalK phosphorylation [19,20].

Figure 4. . Inhibition of the WalK/R system does not lead to death of MRSA persisters or rapid membrane permeabilization.

MRSA persisters were treated with 10X MIC NH125 (A), 10X MIC 16-BAC (B), 10X MIC walrycin B (C) and 0.1% DMSO (D). Persister viablity (solid circles) was measured by serial dilution and plating on TSA plates. Membrane permeability (open circles) was measured spectrophotometrically by monitoring the uptake of SYTOX Green (Ex = 485 nm, Em = 525 nm). The data points on the x-axis are below the level of detection (2 × 102 CFU/ml). Results are shown as means ± SD; n = 3.

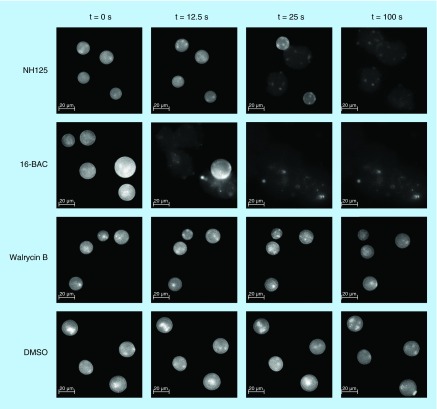

NH125 disrupts giant unilamellar vesicles

To provide direct evidence that NH125 disrupts bacterial membranes, we examined the effects of NH125 on giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs), a biomimetic model of cellular membranes, which is widely used for biophysical studies of lipid bilayer properties and interactions with biomolecules [27,28]. GUVs have been used for elucidating modes of action of membrane-active antimicrobial agents, such as daptomycin [37,45–48]. In this series of experiments, we used GUVs with a phospholipid composition that had been used previously for modeling the anionic bacterial membrane of S. aureus [37,49,50]. As shown in Figure 5 & Supplementary Video 1, 10X MIC (20 µg/ml) NH125 led to bursting of GUVs. Similar to NH125, rupture of GUVs was observed after treating them with 10X MIC (20 µg/ml) 16-BAC (Figure 5 & Supplementary Video 2), consistent with its mode of action described in previous studies [43,44]. For both NH125 and 16-BAC, an expansion of the GUVs was observed before bursting, which is indicative of inflow of the extravesicular solution due to a damaged lipid bilayer (Figure 5 & Supplementary Video 1 & 2). Also, the sudden decrease in the fluorescence observed before bursting of GUVs indicates loss of rhodamine-tagged lipid components, resulting from solubilization of lipid components by 16-BAC and NH125. In contrast, no such disruption of GUVs was observed when they were treated with 10X MIC (40 µg/ml) walrycin B (Figure 5 & Supplementary Video 3). These results show that the major mechanism by which NH125 kills MRSA persisters is by interacting with and disrupting membranes in a manner similar to cationic detergents.

Figure 5. . Time-lapse fluorescence micrograph showing effects of antimicrobial agents on giant unilamellar vesicles.

Giant unilamellar vesicles consisting of DOPC/DOPG (7:3) labeled with 18:1 Liss Rhod PE (0.05%) were treated with 10X MIC NH125, 10X MIC 16-BAC, 10X MIC Walrycin B and 0.1% DMSO. After adding compounds at t = 0 s, changes of giant unilamellar vesicles were observed for 100 s using a fluorescent microscope (40× objective, Ex = 460 nm, Em = 483 nm).

NH125 has less hemolytic activity than 16-BAC

16-BAC is a benzalkonium chloride (BAC) analog, which is commonly used as a component of ophthalmic products, antiseptics, disinfectants and sanitizers [44]. However, it has been reported that BAC is cytotoxic and can cause lysis of human erythrocytes [51], corneal epithelial cells [52] and nasal epithelial cells [53]. Because NH125 disrupts GUVs relatively slowly compared with 16-BAC (Figure 5 & Supplementary Video 1 & 2), we hypothesized that NH125 may be less cytotoxic than 16-BAC. To test this hypothesis, we compared hemolytic activities of NH125 with that of 16-BAC using human erythrocytes. At 8 µg/ml, 16-BAC caused approximately 7% hemolysis and its HC50 (concentration causing 50% hemolysis) was 25 µg/ml (Figure 2). However, 8 µg/ml NH125 did not cause hemolysis and its HC50 was 38 µg/ml, which is approximately 1.5-fold higher than the HC50 of 16-BAC (Figure 2). Considering that 5 µg/ml NH125 is enough to completely eradicate persisters formed by a board spectrum of S. aureus strains (Figure 1), these results suggest that NH125 may be less toxic than 16-BAC and a better alternative for 16-BAC.

Discussion

Persister cells are a nongrowing dormant subpopulation of a bacterial culture showing high tolerance to conventional antibiotics [54,55] and play an important role in the recalcitrance of chronic infections and the antibiotic tolerance of biofilms [12,13,56]. However, currently there are only a few effective ways to treat persisters. Previously, we identified NH125 and found that it kills MRSA persisters and eradicates MRSA biofilms [11]. NH125 was originally synthesized as a potential antimicrobial that inhibits phosphorylation of essential bacterial histidine kinases [19] and showed a strong correlation between antibiotic activity and WalK inhibitory activity [20]. Specifically, subtle structural modifications while maintaining its amphipathic character resulted in the decrease in both the kinase inhibitory activity and antimicrobial activity [19,20]. Further, the WalK/R system is known to regulate biofilm formation and cell wall synthesis [57]. Thiazolidione derivatives targeting WalK show bactericidal activity on Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms where persisters exist [58]. Based on previously published studies of NH125, we hypothesized that the WalK/R system would be a target for killing persisters through membrane permeabilization. Here, we present evidence that the WalK inhibitory activity may not be the mode of action for the persister killing phenotype. The aim of this study was to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of NH125 against a broad spectrum of S. aureus strains and to elucidate the mode of action of NH125 in the killing of MRSA persisters. By comparing the activity of NH125 with its functional analog, walrycin B and its structural analog, 16-BAC, we found that NH125 appears to kill MRSA persisters by disrupting lipid bilayers in a manner apparently independent of WalK/R inhibition.

Although membrane-active agents have excellent potential as antimicrobial agents, with low MICs, fast killing rates and a low possibility of resistance selection, they often exhibit toxicity in mammalian cells [59]. However, membrane-active agents that have high selectivity for bacteria do exist and reduction of toxicity to mammals can be achieved by structural modification [59]. For instance, daptomycin, a lipopeptide antibiotic produced by Streptomyces roseosporus, kills Gram-positive pathogen including MRSA by disrupting the lipid bilayer [60]. Daptomycin is highly selective for bacterial membranes and is considered safe for clinical use, with few deleterious effects, such as an increase of serum creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level [61] and minor side effects on skeletal muscle [62]. Further, α-mangostin, a natural xanthone extracted from a Southeast Asian fruit, Garcinia mangostana, is a membrane-active agent effective in killing MRSA, with known toxicity to mammalian cells [63,64]. However, modification of the α-mangostin structure significantly decreased its toxicity to mammalian cells while maintaining its bacterial killing efficacy [64]. Considering the hemolytic activity of NH125, it appears that this agent is not as selective for bacterial membranes as daptomycin (Figure 2). However, NH125 demonstrated relatively low toxicity to red blood cells compared with 16-BAC, which is widely used as a topical antiseptic [65]. Although further studies concerning efficacy and cytotoxicity are required, we expect that NH125 could be used as part of a topical treatment for the management of chronic skin infections involving persistent bacteria and biofilms. Structure–activity relationship studies correlating chemical structure, antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity need to be performed to explore the possibility of expanding the clinical usage of NH125.

GUVs are a versatile biomembrane-mimicking system that are widely used for studying the interaction between membrane-active compounds and lipid bilayers because their diameter (10–100 µm) is large enough to directly observe dynamic changes in morphology by optical microscopy [66,67]. We used GUVs to investigate the interaction between NH125 and lipid bilayers and observed that NH125 and 16-BAC rapidly solubilized GUVs (Figure 5 & Supplementary Video 1 & 2). The mechanism of rapid solubilization of lipid bilayers by detergents has been well-described [67,68]. First, detergents are inserted into outer monolayers of the lipid bilayers [67,68]. Then, detergents flip into the inner monolayers [67,68]. It is known that rapid solubilization occurs only when detergents can flip into the inner monolayers of the lipid bilayers [67–69]. Following the detergent flip, lipid bilayers are saturated with detergents and mixed lipid/detergent micelles are formed [67,68]. Finally, lipid bilayers are decomposed into the mixed micelles and detergent monomers [67,68]. As shown in Supplementary Video 1, when treated with 10X MIC (20 µg/ml) NH125, the size of the GUVs became increased up to the 24-s mark and then GUVs suddenly burst. This result demonstrates that NH125 is initially incorporated into the outer monolayer of the lipid bilayer by electrostatic forces between the positively charged head of NH125 and anionic GUVs. NH125 then flips into the inner leaflet of the bilayer, fully saturating the lipid bilayers with NH125, thereby causing complete solubilization of the lipid bilayers.

NH125 solubilized GUVs relatively slowly as compared with 16-BAC (Figure 5 & Supplementary Video 1 & 2). The rate of solubilization of lipid bilayers by detergents is dependent on the rate of trans-bilayer movement (known as the flip-flop) [67–69]. Also, the rate of flip-flop is influenced by the polarity and size of the detergent headgroup [70]. In fact, detergents containing a large head group have shown relatively slow flip-flop rate compared with detergents with a smaller head group [68,71,72]. The only structural difference between NH125 and 16-BAC is the relatively large head group of NH125 (Figure 3A & C). Therefore, the relatively large head group of NH125 is likely to be related to the slower rate of solubilization (Figure 5 & Supplementary Video 1 & 2) and may be the reason why we found it to have less hemolytic activity compared with 16-BAC.

Since NH125 shares many common properties with 16-BAC, including antimicrobial activity, membrane permeability and destruction of GUVs, the mode of action of both compounds may be similar. 16-BAC is a homolog of the quaternary ammonium cationic surfactant benzalkonium chloride (BAC), which consists of N-alkyldimethylbenzylammonium chlorides with a C8 to C18 alkyl chain. BAC is known to have two modes of action depending on its concentration [43,44]. First, the positively charged quaternary nitrogen head binds to the acidic head of phospholipids in membranes and then, its alkyl chain embeds into the hydrophobic tails in the membrane core [43,44]. At low concentrations (˜MIC), this interaction increases the surface pressure in the exposed membranes and decreases the fluidity of membranes, which leads to a loss of physiological function, such as osmoregulation, eventually causing bacterial death [43,44]. At high concentrations used in commercial products (0.004–0.02%), BAC solubilizes membrane components, such as lipid A and phospholipids, by forming micellar aggregates, which results in lysis of bacteria [43,44].

Since a decrease in SYTOX green fluorescence can be evidence of degradation of nucleic acids released from lysed bacteria [73], changes in the profiles of SYTOX Green fluorescence as a function of concentrations can be reflective of two different modes of action of 16-BAC depending on the drug concentration (Supplementary Figure 2A). Exposure of bacterial cells with up to 8 µg/ml of 16-BAC caused the SYTOX green fluorescence intensity to increase in a sigmoidal-like pattern and the maximum fluorescence intensity increases in a dose–response manner (Supplementary Figure 2A). At 16 µg/ml of 16-BAC, although the SYTOX green fluorescence over time profile showed a sigmoidal-like pattern, its maximum intensity was lower than that of 8 µg/ml 16-BAC. Further, at 32 µg/ml and 64 µg/ml 16-BAC, a rapid decrease in fluorescence was observed immediately after exposure to 16-BAC and the maximum fluorescence intensity decreased in a dose–response manner (Supplementary Figure 2A). These results suggest that at low concentrations (up to 8 µg/ml), 16-BAC kills MRSA by damaging membranes allowing entry of SYTOX Green but not by solubilizing membrane lipids, whereas at high concentration (over 16–32 µg/ml) 16-BAC appears to lyse persisters most likely by solubilizing membrane lipid bilayers. Similar to 16-BAC, SYTOX Green fluorescence profiles of NH125 also showed two different patterns depending on its concentration (Supplementary Figure 2B). Up to 16 µg/ml, the fluorescence intensity showed a sigmoidal-like pattern and increased in a dose–response manner, whereas at higher concentrations (32–64 µg/ml), the fluorescence intensity showed a dose-dependent decrease (Supplementary Figure 2B). The similar patterns of SYTOX Green fluorescence between NH125 and 16-BAC indicates that NH125 appears to have a similar mode of action as 16-BAC. Whereas 16-BAC started showing a decrease in maximum fluorescence intensity at 16 µg/ml, NH125 exhibited this effect at 32 µg/ml (Supplementary Figure 2), demonstrating that 16-BAC induces membrane solubilization at lower concentrations than NH125. The stronger membrane activity of 16-BAC observed in the fluorescence profiles is consistent with relatively faster rupture of GUVS by 16-BAC (Figure 5) and relatively higher hemolytic activity (Figure 2) compared with NH125.

Conclusion

NH125 kills growing MRSA by multiple modes of action, including inhibition of WalK and membrane disruption. However, the mode of action of NH125 against MRSA persister cells is mostly likely by disrupting membranes in a detergent-like fashion, independent of the inhibition of the WalK/R system. Considering its strong antimicrobial activity against a range of S. aureus strains and relatively low cytotoxicity compared with 16-BAC, NH125 could be a promising lead compound for treating chronic skin infection and an alternative to 16-BAC.

Future perspective

The rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and bacterial persisters are two big challenges in antimicrobial chemotherapy. Antimicrobial agents targeting bacterial membranes are promising candidates against both antibiotic-resistant bacteria and bacterial persisters. In the past, membrane-active agents were ignored as antimicrobial candidates due to their propensity to show toxicity to in mammals. However, the clinical success of daptomycin has led to renewed interest in membrane-active agents and many compounds targeting bacterial membranes are currently under evaluation. Using a broad spectrum of clinical S. aureus strains and GUVs, we demonstrated that NH125 is a membrane-active agent with robust antimicrobial activity against both growing and persister cells. We also demonstrated the NH125 is likely to be less toxic than 16-BAC, which is currently used as a disinfectant. These results suggest that NH125 is a promising candidate for treating chronic skin infection and analogs should be studied to optimize antimicrobial activity and minimize cytotoxicity, followed by in vivo studies to evaluate the potential of NH125.

Executive summary.

Stationary-phase cells of 11 clinical S. aureus isolates showed tolerance to 10X MIC of conventional antibiotics irrespective of whether they were methicillin resistant, which indicates that the persistency of stationary phase cells appears to be a consistent feature of S. aureus strains.

A nonhemolytic concentration of NH125 (5 µg/ml) completely eradicated approximately 5 × 107 CFU/ml persister cells formed by 11 clinical S. aureus isolates within 4 h.

While walrycin B showed antimicrobial activity only against Gram-positive bacteria, NH125 showed antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, similar to 16-BAC.

Unlike walrycin B, both NH125 and 16-BAC induced rapid membrane permeabilization and completely killed MRSA persisters.

Both 16-BAC and NH125 caused expansion of GUVs followed by their rupture, whereas walrycin B did not affect GUVs.

Our results showed that NH125 kills MRSA persisters by disrupting membranes, in a manner most likely independent of WalK/R inhibition.

NH125 showed lower hemolytic activity than 16-BAC.

NH125 could be a promising topical antibiotic candidate against both antibiotic-resistant bacteria and bacterial persisters.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This study was supported by NIH grant P01 AI083214 to EE Mylonakis and FM Ausubel. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Kluytmans J, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms and associated risks. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1997;10(3):505–520. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.3.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorwitz RJ, Kruszon-Moran D, McAllister SK, et al. Changes in the prevalence of nasal colonization with Staphylococcus aureus in the United States, 2001–2004. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;197(9):1226–1234. doi: 10.1086/533494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wendlandt S, Schwarz S, Silley P. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a food-borne pathogen? Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2013;4(1):117–139. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-030212-182653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David MZ, Daum RS. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010;23(3):616–687. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00081-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers HF, DeLeo FR. Waves of resistance: Staphylococcus aureus in the antibiotic era. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7(9):629–641. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otto M. Basis of virulence in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus . Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;64(1):143–162. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Antibiotics for emerging pathogens. Science. 2009;325(5944):1089–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1176667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keren I, Kaldalu N, Spoering A, Wang Y, Lewis K. Persister cells and tolerance to antimicrobials. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2004;230(1):13–18. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00856-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allison KR, Brynildsen MP, Collins JJ. Metabolite-enabled eradication of bacterial persisters by aminoglycosides. Nature. 2011;473(7346):216–220. doi: 10.1038/nature10069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Demonstrates that metabolites make persister cells susceptible to aminoglycosides.

- 10.Conlon BP, Nakayasu ES, Fleck LE, et al. Activated ClpP kills persisters and eradicates a chronic biofilm infection. Nature. 2013;503(7476):365–370. doi: 10.1038/nature12790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Demonstrates that ADEP4 corrupts ClpP, a major protease and induces degradation of proteins, which leads to killing of S. aureus persisters.

- 11.Kim W, Conery AL, Rajamuthiah R, Fuchs BB, Ausubel FM, Mylonakis E. Identification of an antimicrobial agent effective against Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus persisters using a fluorescence-based screening strategy. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0127640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Provides a fluorescence-based strategy to identify antimicrobial agents effective against MRSA persisters.

- 12.LaFleur MD, Qi Q, Lewis K. Patients with long-term oral carriage harbor high-persister mutants of Candida albicans . Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54(1):39–44. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00860-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Provides an evidence that persisters are involved in chronic infectious diseases.

- 13.Mulcahy LR, Burns JL, Lory S, Lewis K. Emergence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains producing high levels of persister cells in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192(23):6191–6199. doi: 10.1128/JB.01651-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Additional evidence that persisters are involved in chronic infectious diseases is described in this report.

- 14.Howden BP, Davies JK, Johnson PDR, Stinear TP, Grayson ML. Reduced vancomycin susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus, including vancomycin-intermediate and heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate strains: resistance mechanisms, laboratory detection and clinical implications. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010;23(1):99–139. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00042-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krell T, Lacal J, Busch A, Silva-Jiménez H, Guazzaroni M-E, Ramos JL. Bacterial sensor kinases: diversity in the recognition of environmental signals. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;64(1):539–559. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gotoh Y, Eguchi Y, Watanabe T, Okamoto S, Doi A, Utsumi R. Two-component signal transduction as potential drug targets in pathogenic bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2010;13(2):232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin PK, Li T, Sun D, Biek DP, Schmid MB. Role in cell permeability of an essential two-component system in Staphylococcus aureus . J. Bacteriol. 1999;181(12):3666–3673. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.12.3666-3673.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun J, Zheng L, Landwehr C, Yang J, Ji Y. Identification of a novel essential two-component signal transduction system, YhcSR, in Staphylococcus aureus . J. Bacteriol. 2005;187(22):7876–7880. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.22.7876-7880.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto K, Kitayama T, Ishida N, et al. Identification and characterization of a potent antibacterial agent, NH125 against drug-resistant bacteria. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2000;64(4):919–923. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This is the first paper to identify the activity of NH125, showing it inhibits histidine protein kinases and has antimicrobial activity.

- 20.Yamamoto K, Kitayama T, Minagawa S, et al. Antibacterial agents that inhibit histidine protein kinase YycG of Bacillus subtilis . Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2001;65(10):2306–2310. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • The authors report inhibition of WalK (also known as YycG) by NH125.

- 21.Watanabe T, Hashimoto Y, Yamamoto K, et al. Isolation and characterization of inhibitors of the essential histidine kinase, YycG in Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus . J. Antibiot. 2003;56(12):1045–1052. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.56.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This report demonstrates the potential of the WalK/R system as a promising target for the development of antibiotics.

- 22.Okada A, Igarashi M, Okajima T, et al. Walkmycin B targets WalK (YycG), a histidine kinase essential for bacterial cell growth. J. Antibiot. 2010;63(2):89–94. doi: 10.1038/ja.2009.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gotoh Y, Doi A, Furuta E, et al. Novel antibacterial compounds specifically targeting the essential WalR response regulator. J. Antibiot. 2010;63(3):127–134. doi: 10.1038/ja.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang R-Z, Zheng L-K, Liu H-Y, et al. Thiazolidione derivatives targeting the histidine kinase YycG are effective against both planktonic and biofilm-associated Staphylococcus epidermidis . Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2012;33(3):418–425. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe T, Igarashi M, Okajima T, et al. Isolation and characterization of signermycin B, an antibiotic that targets the dimerization domain of histidine kinase WalK. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56(7):3657–3663. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06467-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Igarashi M, Watanabe T, Hashida T, et al. Waldiomycin, a novel WalK-histidine kinase inhibitor from Streptomyces sp. MK844-mF10. J. Antibiot. 2013;66(8):459–464. doi: 10.1038/ja.2013.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walde P, Cosentino K, Engel H, Stano P. Giant vesicles: preparations and applications. Chembiochem. 2010;11(7):848–865. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Provides an excellent review of GUVs and their application in a broad range of fields.

- 28.Kahya N. Protein-protein and protein-lipid interactions in domain-assembly: lessons from giant unilamellar vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1798(7):1392–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baba T, Takeuchi F, Kuroda M, et al. Genome and virulence determinants of high virulence community-acquired MRSA. Lancet. 2002;359(9320):1819–1827. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08713-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garsin DA, Sifri CD, Mylonakis E, et al. A simple model host for identifying Gram-positive virulence factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98(19):10892–10897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191378698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Junior JC, Fuchs BB, Sabino CP, et al. Photodynamic and antibiotic therapy impair the pathogenesis of Enterococcus faecium in a whole animal insect model. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e55926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith MG, Gianoulis TA, Pukatzki S, et al. New insights into Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenesis revealed by high-density pyrosequencing and transposon mutagenesis. Genes Dev. 2007;21(5):601–614. doi: 10.1101/gad.1510307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rahme LG, Stevens EJ, Wolfort SF, Shao J, Tompkins RG, Ausubel FM. Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science. 1995;268(5219):1899–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.7604262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajamuthiah R, Jayamani E, Conery AL, et al. A defensin from the model beetle Tribolium castaneum acts synergistically with telavancin and daptomycin against multidrug resistant Staphylococcus aureus . PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6):e0128576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Wayne, PA, USA: Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard 9th edition. CLSI document M07-A9. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Angelova MI, Soléau S, Méléard P, Faucon F, Bothorel P. Preparation of giant vesicles by external AC electric fields. Kinetics and applications. Prog. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1992;89:127–131. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Y-F, Sun T-L, Sun Y, Huang HW. Interaction of daptomycin with lipid bilayers: a lipid extracting effect. Biochemistry. 2014;53(33):5384–5392. doi: 10.1021/bi500779g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mertins O, Dimova R. Insights on the interactions of chitosan with phospholipid vesicles. Part II: Membrane stiffening and pore formation. Langmuir. 2013;29(47):14552–14559. doi: 10.1021/la4032199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dubrac S, Msadek T. Identification of genes controlled by the essential YycG/YycF two-component system of Staphylococcus aureus . J. Bacteriol. 2004;186(4):1175–1181. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.4.1175-1181.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rice LB. Federal funding for the study of antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: no ESKAPE. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;197(8):1079–1081. doi: 10.1086/533452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howell A, Dubrac S, Noone D, Varughese KI, Devine K. Interactions between the YycFG and PhoPR two-component systems in Bacillus subtilis: the PhoR kinase phosphorylates the non-cognate YycF response regulator upon phosphate limitation. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;59(4):1199–1215. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.05017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gueriri I, Bay S, Dubrac S, Cyncynatus C, Msadek T. The Pta-AckA pathway controlling acetyl phosphate levels and the phosphorylation state of the DegU orphan response regulator both play a role in regulating Listeria monocytogenes motility and chemotaxis. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;70(6):1342–1357. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McDonnell G, Russell AD. Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action and resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999;12(1):147–179. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Provides a thoughtful review of various antiseptics and disinfectants, including BAC and their modes of action.

- 44.Gilbert P, Moore LE. Cationic antiseptics: diversity of action under a common epithet. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005;99(4):703–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Reviews cationic antiseptics including BAC and their modes of action.

- 45.Tamba Y, Yamazaki M. Single giant unilamellar vesicle method reveals effect of antimicrobial peptide magainin 2 on membrane permeability. Biochemistry. 2005;44(48):15823–15833. doi: 10.1021/bi051684w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ambroggio EE, Separovic F, Bowie JH, Fidelio GD, Bagatolli LA. Direct Visualization of Membrane Leakage Induced by the Antibiotic Peptides: Maculatin, Citropin and Aurein. Biophys. J. 2005;89(3):1874–1881. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.066589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee C-C, Sun Y, Qian S, Huang HW. Transmembrane pores formed by human antimicrobial peptide LL-37. Biophys. J. 2011;100(7):1688–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y, Corbitt TS, Jett SD, et al. Direct visualization of bactericidal action of cationic conjugated polyelectrolytes and oligomers. Langmuir. 2012;28(1):65–70. doi: 10.1021/la2044569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ganewatta MS, Chen YP, Wang J, et al. Bio-inspired resin acid-derived materials as anti-bacterial resistance agents with unexpected activities. Chem. Sci. 2014;5(5):2011–2016. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Caillon L, Killian JA, Lequin O, Khemtémourian L. Biophysical investigation of the membrane-disrupting mechanism of the antimicrobial and amyloid-like peptide dermaseptin S9. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e75528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cadwallader DE, Ansel HC. Hemolysis of erythrocytes by antibacterial preservatives II. Quaternary ammonium salts. J. Pharm. Sci. 1965;54(7):1010–1012. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600540712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cha SH, Lee JS, Oum BS, Kim CD. Corneal epithelial cellular dysfunction from benzalkonium chloride (BAC) in vitro . Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2004;32(2):180–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2004.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ho C-Y, Wu M-C, Lan M-Y, Tan C-T, Yang A-H. In vitro effects of preservatives in nasal sprays on human nasal epithelial cells. Am. J. Rhinol. 2008;22(2):125–129. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lewis K. Persister cells. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;64(1):357–372. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• A considered expert in the field, Lewis, provides a review of the biological properties of persisters and mechanism of persister formation.

- 55.Helaine S, Kugelberg E. Bacterial persisters: formation, eradication and experimental systems. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22(7):417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Reviews current strategies to kill persisters.

- 56.Spoering AL, Lewis K. Biofilms and planktonic cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa have similar resistance to killing by antimicrobials. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183(23):6746–6751. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.23.6746-6751.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dubrac S, Boneca IG, Poupel O, Msadek T. New insights into the WalK/WalR (YycG/YycF) essential signal transduction pathway reveal a major role in controlling cell wall metabolism and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus . J. Bacteriol. 2007;189(22):8257–8269. doi: 10.1128/JB.00645-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang R-Z, Zheng L-K, Liu H-Y, et al. Thiazolidione derivatives targeting the histidine kinase YycG are effective against both planktonic and biofilm-associated Staphylococcus epidermidis . Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2012;33(3):418–425. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hurdle JG, O'Neill AJ, Chopra I, Lee RE. Targeting bacterial membrane function: an underexploited mechanism for treating persistent infections. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9(1):62–75. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Reviews membrane-active agents and their possibility for treating persistent infection.

- 60.Straus SK, Hancock REW. Mode of action of the new antibiotic for Gram-positive pathogens daptomycin: comparison with cationic antimicrobial peptides and lipopeptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1758(9):1215–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Figueroa DA, Mangini E, Amodio-Groton M, et al. Safety of high-dose intravenous daptomycin treatment: three-year cumulative experience in a clinical program. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49(2):177–180. doi: 10.1086/600039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kostrominova TY, Coleman S, Oleson FB, Faulkner JA, Larkin LM. Effect of daptomycin on primary rat muscle cell cultures in vitro . In vitro Cell. Dev. Biol.-Animal. 2010;46(7):613–618. doi: 10.1007/s11626-010-9311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koh J-J, Qiu S, Zou H, et al. Rapid bactericidal action of alpha-mangostin against MRSA as an outcome of membrane targeting. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1828(2):834–844. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zou H, Koh J-J, Li J, et al. Design and synthesis of amphiphilic xanthone-based, membrane-targeting antimicrobials with improved membrane selectivity. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56(6):2359–2373. doi: 10.1021/jm301683j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Müller G, Kramer A. Biocompatibility index of antiseptic agents by parallel assessment of antimicrobial activity and cellular cytotoxicity. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008;61(6):1281–1287. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dimova R, Aranda S, Bezlyepkina N, Nikolov V, Riske KA, Lipowsky R. A practical guide to giant vesicles. Probing the membrane nanoregime via optical microscopy. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2006;18(28):S1151–S1176. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/18/28/S04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sudbrack TP, Archilha NL, Itri R, Riske KA. Observing the solubilization of lipid bilayers by detergents with optical microscopy of GUVs. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115(2):269–277. doi: 10.1021/jp108653e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Describes how detergents solubilize GUVs.

- 68.Lichtenberg D, Ahyayauch H, Goñi FM. The mechanism of detergent solubilization of lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 2013;105(2):289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Describes the mechanisms of detergent solubilization of lipid bilayers and the importance of the flip-flop rate of a detergent in the solubilization.

- 69.Kragh-Hansen U, le Maire M, Møller JV. The mechanism of detergent solubilization of liposomes and protein-containing membranes. Biophys. J. 1998;75(6):2932–2946. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77735-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stuart MCA, Boekema EJ. Two distinct mechanisms of vesicle-to-micelle and micelle-to-vesicle transition are mediated by the packing parameter of phospholipid–detergent systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768(11):2681–2689. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cócera M, Lopez O, Coderch L, Parra JL, la Maza de A. Influence of the level of ceramides on the permeability of stratum corneum lipid liposomes caused by a C12-betaine/sodium dodecyl sulfate mixture. Int. J. Pharm. 1999;183(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(99)00084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heerklotz H. Membrane stress and permeabilization induced by asymmetric incorporation of compounds. Biophys. J. 2001;81(1):184–195. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75690-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Roth BL, Poot M, Yue ST, Millard PJ. Bacterial viability and antibiotic susceptibility testing with SYTOX green nucleic acid stain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997;63(6):2421–2431. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2421-2431.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • The first to introduce a membrane-impermeable DNA-binding dye, SYTOX Green.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.