Abstract

Background

Countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) have experienced a rapid increase in their proportion of older people. This region is marked by a high prevalence of chronic diseases and disabilities among aging adults. Frailty appears in the context of LAC negatively affecting quality of life among many older people.

Aim

To investigate the prevalence of frailty among community-dwelling older people in LAC through a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

A literature search was performed in indexed databases and in the grey literature. Studies investigating the prevalence of frailty with representative samples of community-dwelling older people in Latin America and the Caribbean were retrieved. Independent investigators carried out the study selection process and the data extraction. A meta-analysis and meta-regression were performed using STATA 11 software. The systematic review was registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews under the number CRD42014015203.

Results

A total of 29 studies and 43,083 individuals were included in the systematic review. The prevalence of frailty was 19.6% (95% CI: 15.4–24.3%) in the investigated region, with a range of 7.7% to 42.6% in the studies reviewed. The year of data collection influenced the heterogeneity between the studies.

Conclusion

Frailty is very common among older people in LAC. As a result, countries in the region need to adapt their health and social care systems to demands of an older population.

Introduction

Frailty is characterized by an accelerated decrease in several inter-related physiological systems resulting in the malfunction of homeostatic mechanisms [1]. This condition is more prevalent among older people, negatively affects people’s quality of life, and predicts disability, falls, hospitalization, and mortality [2, 3]. As a result, frail older people require extra care, which impacts individual and governmental financial planning [4].

Frailty has been studied extensively in recent years, and its prevalence has been investigated more thoroughly in North America, Europe, and developed countries, where it has appeared to increase with age and be higher among women [4, 5]. However, there is no consensus regarding the prevalence of frailty worldwide [4].

The lack of agreement regarding the best frailty measurements and diagnostic criteria has also been stated in the literature [6, 7]. Some well accepted conceptual models define frailty as a purely physical syndrome, while others include psychological and social aspects in its definition [3, 6, 8]. Based on these conceptual models, a variety of instruments have been developed to assess frailty. The Frailty Phenotype, for instance, classified frailty based on five physical criteria, while the Tilburg Frailty Indicator and the Frailty Index added social and psychological domains to their definition of frailty [3, 8–9].

The Frailty Phenotype is the most commonly used way of measuring frailty. It was developed and operationalized by Fried et al. (2001) and used data from the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) Cohort [3]. However, modified versions of the proposed Phenotype have often been used because it is not always feasible to assess all the physical criteria in the same way measured in the CHS Cohort [10]. As different conceptual models influence the selected characteristics for defining frailty [7], it has been observed that the prevalence of frailty varies according to each adopted definition and way of measurement [4, 10–12].

Few studies investigating the prevalence of frailty in less-developed countries are found in the literature. Countries in Latin American and the Caribbean (LAC) are experiencing a rapid increase in the proportion of aging citizens and this process is likely to continue for the next three decades [13–14]. Rising longevity in countries with poor standards of living increases the likelihood of having a larger population of frail older adults [13–14]. Moreover, compared to developed nations, Latin American adults are facing a higher number of chronic diseases and disabilities as they age [12, 15–16]. A study conducted in low- and middle-income countries reported similar or higher incidence of dementia compared with countries of high-income [17]. As a result, Latin American countries will need to adapt their institutions and public policies to the new challenges that arise from a less healthy older population [5, 12, 15].

Stating the prevalence of frailty is challenging due to the variety of frailty measurements. However, in an under researched region where an aging population is combined with marked social disadvantages having an estimated prevalence may contribute to planning health and social care policies. Some studies have investigated frailty in LAC cities, but, as far we are aware, no systematic review on the topic has been carried out thus far. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the pooled prevalence of frailty among community-dwelling older people in LAC through a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Materials and Methods

Register and protocol

This study was registered at Prospero (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) under the number CRD42014015203.

Eligibility criteria

We selected cross-sectional surveys and baseline assessments of longitudinal studies with representative samples of community-dwelling older men and women aged 60 years and above living in the Latin American and Caribbean region. Eligible studies had to report their working definition of frailty, to state the prevalence of frailty or to supply data that allowed us to calculate frailty prevalence measures. We excluded studies stating mean frailty scores without cutoff points for frailty categories and studies that examined a disease-specific population. The definition of frailty and sample size were not part of the criteria for excluding studies in this review. There was no limit for language, publication date or status. The minimum age of 60 years in reference to the older population was assumed according to the cutoff agreed to by the United Nations [18].

Information sources and search strategy

The literature search for potential eligible studies was performed between 5th and 7th May 2016 using the following electronic databases: MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, Lilacs, SciELO, Google Scholar, Web of Science, Scopus, ProQuest, CINAHL, and academic works (theses database). Moreover, studies were also selected through manual search of reference citations. The search strategy was developed using Mesh terms for PubMed, EMTREE terms for Embase, and a combination of keywords. For example, the full electronic search strategy used at PubMed was: (“Frail Elderly” [Mesh] OR "Frail Elderly” [TIAB] OR “Frailty” OR “Frail Older People”) AND ("Prevalence" OR “Frequency”). The search strategy was slightly modified based on each database (S1 Table).

Study selection process

The study selection process was carried out in two stages by four independent investigators (FAFM, PPSP, KRCA, and ACGF), each record was independently read by two authors. Records (articles) were selected based on their titles and abstracts; duplicate records were excluded. The remaining records were read in their entireties, and those suitable for the review were selected. In cases where a consensus could not be reached by the two authors, a third author helped make a decision regarding the paper selection. Sometimes, a record could describe more than one study; thus, the total number of individual studies was considered at the end of the review. When different studies shared the same population, the study that provided the largest sample size or the one with more detailed information about the participants and frailty definition was chosen–these criteria have been used by other authors [4]. Studies using modified versions of the Frailty Phenotype (i.e., that adopted different metrics or criterion) were also selected.

Data extraction and quality assessment of studies

Three authors (FAFM, PPSP, and KRCA) independently extracted data onto a standardized datasheet. In cases of disagreement, decisions were made by consensus. The data extracted included studies’ features, sample sizes, and prevalence of frailty. In cases that a record compared two prevalence measures from different definitions of frailty, the lower prevalence was the chosen one in order to be more conservative. We tried to contact all the correspondent authors to gather data to complete the data extraction form for each study.

The quality assessments of the studies were carried out based on a tool described by Munn et al., 2015 [19–20]. This tool includes nine items for critical appraisals of the methodological quality of studies reporting prevalence data. For each criterion met, the study received a “yes”. The total number of “yes” answers was counted per study. The larger the number of “yes”, the lesser the risk of bias in the study. As one of the items presented in the tool inquired about the validity of the methods used to identify the condition, we considered modified versions of the Frailty Phenotype as a valid method in this item.

Data analysis

The main outcome in this review was the prevalence of frailty in older people in LAC with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

A meta-analysis of a random-effects model was chosen a priori. We used the metaprop ftt command in STATA (version 11.0) to perform the analysis as it incorporates the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine method to stabilize the variance [21–22]. The chi-squared test was applied to measure heterogeneity between studies at the p < 0.10 significance level. We adopted this p-value over the standard p < 0.05 to be more conservative as low power is attributed to the chi-squared test in meta-analyses when a small number of studies or studies of small sample size are considered [23]. The magnitude of inconsistency was measured using I-squared (I2) statistics. High heterogeneity was considered when I2 was over 75%, moderate when it was between 25% and 75%, and low when I2 was less than 25% [23–26].

To explore potential sources of heterogeneity, sensitivity and subgroup analyses of the prevalence were carried out. Subgroups were divided by sex (men versus women), region (North America versus Central America versus South America), frailty definition (Frailty Phenotype versus Modified Frailty Phenotype versus Edmonton Frailty Scale versus Five physical criteria), and country (Brazil versus other countries). A meta-regression was performed considering p < 0.05 to determine whether possible covariates such as the sample size, mean age, proportion of women, data collection year (represented by the last year of the data collection), and study quality could explain the heterogeneity between studies. Meta-regressions were carried out in each subgroup analysis as well [26]. Potential publication bias (or the small-studies effect) was analyzed using Funnel plots and the Egger’s test [26–28]. We used STATA software (version 11.0) for all the statistical analysis.

Results

Selection process and characteristics of studies

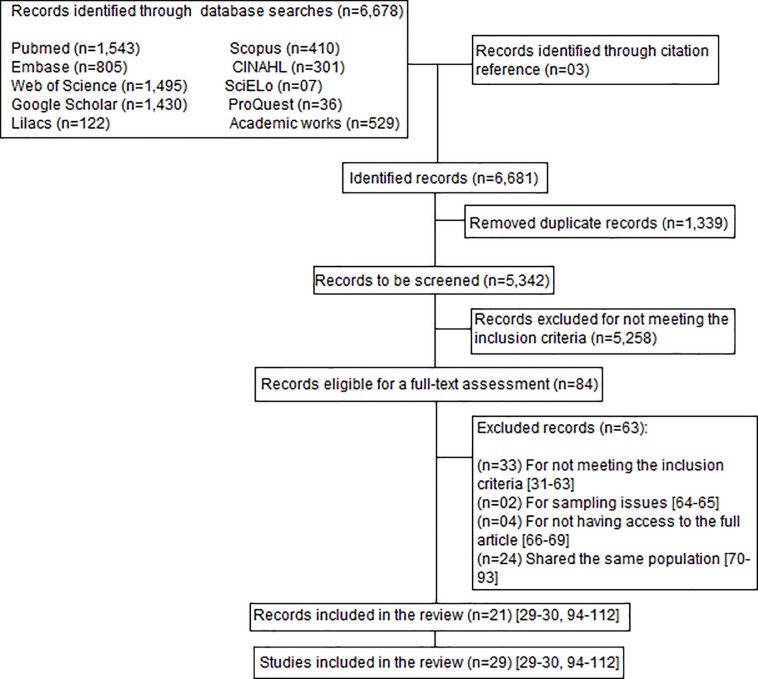

The literature search yielded 6,678 records. After removing duplicates and assessing titles, abstracts, and inclusion criteria, 84 manuscripts were submitted for a complete reading. From these, 21 were included in the review. Two records [29–30] contained information on prevalence from four studies each. Therefore, a total of 29 studies were included in the systematic review. Fig 1 displays details about the selection process and the reasons for the exclusion of records [29–112].

Fig 1. Flowchart of the study selection process.

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the studies [29–30, 94–112]. A total of 43,083 participants were included in the review; the majority of the studies were composed of women, and the feminine proportions in the samples ranged from 52.2% [97] to 67.7% [101]. Twenty two studies in this review used modified versions of the Frailty Phenotype to define frailty [29–30, 94–97, 99, 102–104, 108–109, 100–111], four studies used the Frailty Phenotype according to the operationalization used in the CHS [101, 106, 110, 112], two studies used the Edmonton Frailty Scale [98, 105], and one used five physical tests to define frailty [107]. Data were stratified by sex in 19 studies [29, 94–95, 97, 99, 101–104, 106–111]. Regarding geographic regions, 20 studies were performed in South America [29–30, 97, 101, 95–96, 98, 100, 102–106, 109–112]; four were performed in Central America [29–30, 107], and five were performed in North America [29–30, 94, 99, 108]. The quality assessment for each study is presented in the S2 Table. All studies seemed to be of good quality, with the number of “yes” answers varying between 7 and 9 with a mean of 8.3. A meta-analysis was performed for all of the 29 included studies. The data extraction form is presented in the S3 Table.

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies.

| Author, publication year | Place | Year of data collection | Study group | Study design | Frailty definition | Sample size (n) | Mean age | Women (%) | Frailty Prevalence (%) | Confidence Interval (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguilar-Navarro et al., 2015 [94] | Mexico | 2001 | Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS) | Baseline of a longitudinal study | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 5,644 | 68.7 | 53.6 | 37.2 | NA |

| Alvarado et al., 2008 [29] | Bridgetown, Barbados | 1999–2000 | SABE | Population-based | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 1,446 | NA | 61.0 | 26.7 | NA |

| Alvarado et al., 2008 [29] | São Paulo, Brazil | 1999–2000 | SABE | Population-based | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 1,879 | NA | 59.0 | 40.6 | NA |

| Alvarado et al., 2008 [29] | Santiago, Chile | 1999–2000 | SABE | Population-based | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 1,220 | NA | 65.7 | 42.6 | NA |

| Alvarado et al., 2008 [29] | Havana, Cuba | 1999–2000 | SABE | Population-based | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 1,726 | NA | 62.8 | 39.0 | NA |

| Alvarado et al., 2008 [29] | Mexico City, Mexico | 1999–2000 | SABE | Population-based | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 1,063 | NA | 56.4 | 39.5 | NA |

| Andrade et al., 2013 [95] | São Paulo, Brazil | 2006 | SABE—São Paulo | Cross-sectional | Modified version of Fried Phenotype | 1,374 | NA | 59.7 | 8.5 | NA |

| Corona et al., 2015 [96] | São Paulo, Brazil | 2010 | SABE—São Paulo | Cross-sectional | Modified version of Fried Phenotype | 1,256 | 70.0 | 60.9 | 8.0 | 6.3–10.2 |

| Curcio et al., 2014 [97] | Four cities in Colombia | 2005 | NA | Survey | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 1,878 | 70.9 | 52.2 | 12.2 | 6.8–17.0 |

| Fohn et al., 2013 [98] | Ribeirão Preto, Brazil | 2010–2011 | NA | Cross-sectional | Edmonton Frail Scale | 240 | 73.5 | 62.9 | 39.2 | NA |

| García-Peña et al., 2016 [99] | Mexico | 2012 | Mexican Health and Ageing Study (MHAS) | Cross-sectional | Modified version of Fried Phenotype | 1,108 | 69.8 | 54.6 | 24.9 | NA |

| Jotheeswaran et al., 2015 [30] | Cuba | 2003–2007 | 10/66 Dementia Research Group’s | Population-based | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 2,813 | 75.2 | 65.0 | 21.0 | NA |

| Jotheeswaran et al., 2015 [30] | Domican Republic | 2003–2007 | 10/66 Dementia Research Group’s | Population-based | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 2,011 | 75.4 | 66.3 | 34.6 | NA |

| Jotheeswaran et al., 2015 [30] | Venezuela | 2003–2007 | 10/66 Dementia Research Group’s | Population-based | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 1,997 | 72.3 | 63.2 | 11.0 | NA |

| Jotheeswaran et al., 2015 [30] | Mexico | 2003–2007 | 10/66 Dementia Research Group’s | Population-based | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 2,003 | 74.2 | Urban population: 66.5 Rural population: 60.9 | Urban population: 10.1 Rural population: 8.5 | NA |

| Jotheeswaran et al., 2015 [30] | Peru | 2003–2007 | 10/66 Dementia Research Group’s | Population-based | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 1,933 | 74.5 | Urban population: 64.7 Rural population: 53.2 | Urban population: 25.9 Rural population: 17.2 | NA |

| Junior et al., 2914 [100] | Lafaiete Coutinho, Brazil | 2011 | Nutritional status, risk behaviors and health conditions of the elderly people of Lafaiete Coutinho-BA. | Cross-sectional | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 286 | NA | NA | 23.8 | NA |

| Neri et al., 2013 [101] | Belém, Brazil, Parnaíba, Brazil, Campina Grande, Brazil, Poços de Caldas, Brazil, Ermelino Matarazzo, Brazil, Campinas, Brazil, Ivoti, Brazil | 2008–2009 | FIBRA NETWORK | Cross-sectional | Fried Phenotype (CHS) | 3,478 | 72.9 | 67.7 | 9.0 | NA |

| Ocampo-Chaparro et al., 2013 [102] | Cali, Colombia | 2009 | NA | Population-based | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 314 | NA | NA | 12.7 | NA |

| Pegarori et al., 2014 [103] | Uberaba, Brazil | 2012 | FIBRA NETWORK | Cross-sectional | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 958 | 73.8 | 64.4 | 12.8 | 10.87–15.11 |

| Pinedo et al., 2010 [104] | Lima, Peru | NA | NA | Cross-sectional | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 246 | 69.9 | 59.8 | 7.7 | NA |

| Ramos et al., 2015 [105] | Montes Claros, Brazil | 2013 | NA | Population-based | Edmonton Frail Scale | 639 | 70.6 | 64.0 | 33.6 | NA |

| Ricci et al., 2014 [106] | Barueri, Brazil, Cuiabá, Brazil | 2009–2010 | FIBRA NETWORK | Population-based | Fried Phenotype (CHS) | 761 | 71.9 | 64.3 | 9.7 | NA |

| Rosero-Bixby et al., 2009 [107] | Costa Rica | 2004–2006 | CRELES | Baseline of a longitudinal study | Five physical tests: grip strength, pulmonary peak flow, standing up from a chair, picking an object up from the floor, and standing and walking 3m | 2,827 | NA | 52.4 | 23.6 | 21.1–26.3 |

| Ruiz-Arregui et al., 2013 [108] | Coyoacan, Mexico | 2008–2009 | Coyoacán Cohort Study | Baseline of a longitudinal study | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 927 | 79.5 | 54.9 | 14.1 | 11.9–16.5 |

| Samper-Ternent et al., 2016 [109] | Bogotá, Colombia | 2012 | SABE (Bogotá Study) | Cross-sectional | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 1,442 | 70.7 | 61.0 | 9.4 | NA |

| Sousa et al., 2012 [110] | Santa Cruz, Brazil | NA | FIBRA Network | Cross-sectional | Fried Phenotype (CHS) | 391 | 74.0 | 61.4 | 17.1 | NA |

| Tribess et al., 2012 [111] | Uberaba, Brazil | 2010 | Population Study of Physical Activityand Aging (Estudo Populacional de Atividade Física e Envelhecimento) | Cross-sectional | Modified version of Frailty Phenotype | 622 | 71.0 | 65.0 | 19.9 | NA |

| Vieira et al., 2013 [112] | Belo Horizonte, Brazil | 2008–2009 | FIBRA NETWORK | Population-based | Fried Phenotype (CHS) | 601 | 74.3 | 66.2 | 8.7 | NA |

Frailty Prevalence

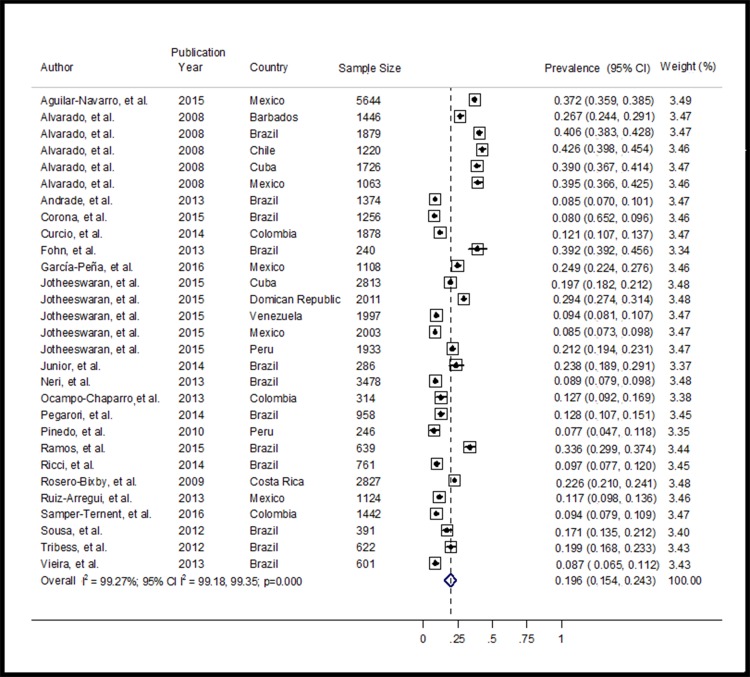

The prevalence of frailty in Latin America and the Caribbean was 19.6% (95% CI: 15.4–24.3; 29 studies; 43,083 individuals; I2 = 99.3%, 95% CI: 99.18–99.35) with a range of 7.7% to 42.6% in the studies reviewed (Fig 2). Visual inspection of the funnel plot revealed asymmetry, and the Egger’s test findings suggested that publication bias might have been present (p = 0.040). We used the “trim and fill” approach to try to account for non-published results and the prevalence of frailty was 13.1% (95% CI = 8.2–17.9) [113]. Between-study heterogeneity was identified (Chi-square = 3848.02, df = 28, p<0.001). A meta-regression indicated that the year of data collection partly explained the heterogeneity observed in the prevalence of frailty (p = 0.003; R2 = 28.7%). S1, S2, and S3 Figs display the funnel plot, the trim and fill, and meta-regression graphs respectively.

Fig 2. Meta-analysis of the prevalence of frailty in LAC.

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

We identified four studies with sample size larger than 2,500 which we considered outliers compared to the sample size of other studies included in this review [30, 94, 101, 107]. We performed a meta-analysis without these studies and the results were similar (Prevalence = 19.4%, CI = 14.8–24.5; I2 = 99.1, p<0.001).

A subgroup analysis revealed high heterogeneity in all analyzed categories, except for the one defining frailty according to the Edmonton Frailty Scale that presented moderate heterogeneity (Table 2). By considering the overlap among the confidence intervals in each subgroup, no differences in prevalence were observed for the population sex and for the country subgroup. However, frailty prevalence was higher in Central than South America, when the Edmonton Scale was used, and when modified versions of Frailty Phenotype were used compared to the traditional version.

Table 2. Subgroup analyses by sex, region, frailty definition, and country.

| Subgroups | Number of studies [references] | Total number of participants | Frailty prevalence, % (95% CI) | I2(%) | p-value (chi-square) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 19 [29, 94–95, 97, 99, 101–104,106–111] | 17,669 | 23.4 (16.6–30.9) | 99.2 | <0.001 |

| Male | 19 [29, 94–95, 97, 99, 101–104, 106–111] | 12,282 | 15.0 (11.1–19.4) | 97.5 | <0.001 |

| Region | |||||

| North America | 5[29–30, 94, 99, 108] | 10,942 | 23.0 (10.9–38.0) | 99.6 | <0.001 |

| Central America | 4 [29–30, 107] | 8,010 | 29.3 (22.6–36.4) | 97.9 | <0.001 |

| South America | 20 [29–30, 95–98, 100–106, 109–112] | 21,515 | 17.1 (12.6–21.1) | 99.0 | <0.001 |

| Frailty definition | |||||

| Frailty Phenotype | 4 [101, 106, 110, 112] | 5,231 | 10.6 (8.0–13.6) | 86.8 | <0.001 |

| Modiefied Frailty Phenotype | 22 [29–30, 94–97, 99–100, 102–104, 108–109, 111] | 34,343 | 20.0 (15.0–25.5) | 99.3 | <0.001 |

| Edmonton Frailty Scale | 2 [98, 105] | 879 | 35.8 (30.6–41.2) | 56.9 | 0.128 |

| Five physical tests | 1 [107] | 2,827 | 22.6 (21.1–24.2) | - | - |

| Country | |||||

| Brazil | 12[29, 95–96, 98, 100–101, 103, 105–106, 110–112] | 12,485 | 17.9 (11.3–25.6) | 99.1 | <0.001 |

| Other countries | 17[29–30, 94, 97, 99, 102, 104, 107–109] | 30,795 | 20.9 (15.6–26.8) | 99.3 | <0.001 |

Meta-regressions performed in subgroups indicated that not all of the analyzed covariates were significantly possible causes of the high heterogeneity between the studies (p>0.05). However, the year of data collection partly explained the heterogeneity observed in the subgroups of women (p<0.001; R2 = 62.4%), men (p<0.05; R2 = 43.2%), in the modified version of Frailty Phenotype (p<0.001; R2 = 51.5%), and in the other countries subgroup (p = 0.001; R2 = 53.1%). Sample size, mean age, study quality, and the proportion of women were not found to explain the between-sample heterogeneity in any subgroup.

Discussion

In LAC, on average, 19.6% of community-dwelling older people are frail. This prevalence ranges from 7.7% [104] to 42.6% [29] according to the studies selected for this review.

Previous studies

The estimated prevalence of frailty in LAC is different to those observed in studies conducted in more developed regions. In 2012, a systematic review carried out with people aged 65 years and over in countries in Europe, North America, and Oceania investigated the average prevalence of frailty when using physical and broader definitions of the syndrome. The prevalence of physical frailty was 9.9%, and when broader definitions including psychological and social aspects were considered, the prevalence rose to 13.6% [4]. A cross-sectional analysis performed in 10 European countries revealed that 17% of the individuals aged at least 65 years were frail [5]. In a cohort study of community-dwelling older Japanese aged 65 years and above, the estimated prevalence of frailty was 12.5% [114].

A systematic review conducted with 21 studies from developing countries showed that measures of prevalence varied between 5.4% and 44.0% in community-dwelling older people aged 55 years and over. A summary measure of the prevalence was not estimated by the authors [115]. Another study carried out with people aged 50 years and over showed that lower income countries such as China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia Federation, and South Africa had lower levels of frailty compared to higher income countries from Europe [116].

We note that studies assessing frailty use different age cutoffs to classify older people. According to the World Health Organization, a minimum age of 65 years characterizes an older person in developed countries, while in developing countries this cutoff is 60 years and over [18]. Therefore, it is not possible to establish a direct comparison between the above referred prevalence measures and the one estimated in this review. However, in general, one may note a trend of lower prevalence of frailty in developed countries related to the estimated prevalence for LAC in this study.

Differences among frailty prevalence estimates between LAC and developed countries may be due to a number of factors. For instance, lifestyles, health statuses, and demographic and socioeconomic characteristics vary greatly between countries at different stages of development. In LAC, approximately 1 out of 5 older persons is frail. This large proportion of frail older people is likely to increase the demand for health and social services.

Our results showed no differences in prevalence between men and women. However, the literature shows that women are commonly more frail than men [5, 29, 117–120]. Because women live longer and generally have a larger number of comorbidities [121], a greater prevalence of frailty is expected in the female population. A study conducted in Europe showed that while women have a shorter disability-free life expectancy, men have a shorter life expectancy with frailty [122]. We could not assess the prevalence of frailty by age group in this review because the studies report different age categories and distributions. However, it is well established in the literature that frailty increases with age [29, 119–120] because as people age, they accumulate deficits and become more vulnerable to adverse health outcomes [7].

The prevalence of frailty in Central America was higher than in South America. However, this result should be interpreted with caution given the greater number of studies conducted in South America compared with the smaller number of studies conducted in Central America. The variability of sample size in the studies might have also contributed to an unbalanced comparison between the regions. The 19.6% estimated prevalence of frailty in LAC ranges from 7.7% to 42.6% among the individual studies selected in the review. These prevalence measures are from an array of studies conducted in different cities in LAC and show how varied the prevalence of frailty can be among individual studies in the region.

High levels of heterogeneity were observed between almost all of the prevalence measures in this review. The exception was the subgroup that defined frailty using the Edmonton Frailty Scale that presented non-significant heterogeneity. However, this result should not be automatically interpreted as between-study homogeneity because of the small number of studies in the subgroup–only two [23]. Our results showed that a possible methodological source of the observed heterogeneity was the year of data collection. Between-study heterogeneity may be influenced by the data collection year because more recent investigations provide information about younger cohorts of older persons who might have benefited from better access to healthcare, while people from older cohorts may not have had such access [13].

Limitations and strengths of the study

This review included a number of studies conducted in different cities and different countries; thus, caution is required when interpreting the results. The high level of heterogeneity among the studies may be related to the research designs of the primary studies selected by this review, different sample sizes, health statuses, and cultural, demographic, and socioeconomic differences among the countries investigated [24]. Although these countries are in the same region, they are quite disparate in economic and cultural terms. Consequently, these discrepancies might influence the heterogeneity observed between studies. The unbalanced distribution of studies among the three American regions is another consideration factor when interpreting the results. We could not assess frailty distributions by age due to study differences when reporting the age categories. Publication bias might have been present in this review, although we have tried to understand it using the “trim and fill” approach.

One of the strengths of this review is that an extensive search of studies was carried out in databases and in the grey literature with the aim of diminishing the risk of losing studies (selection bias). Moreover, possible causes of heterogeneity were investigated through meta-regression and sensitivity and subgroup analyses to allow for a better understanding of the high variability between studies. In addition, authors from the selected original studies were contacted for gathering additional data for this review.

Frailty is a topic that requires further investigation. Although the population of older people in LAC is growing fast and need attention, there are not enough investigations regarding the subject in the region. Future studies should detail the prevalence of frailty in each Latin American and Caribbean country as well as in the region as a whole to obtain more precise estimates. Moreover, consensus regarding the use of a unified tool for measuring frailty is needed, as it would allow more comprehensive comparisons to be made between primary studies.

This systematic review analyzed the available literature regarding the prevalence of frailty in people living in an under-researched region. It revealed that roughly one in five community-dwelling older persons is frail in LAC. This is a massive estimate in a region of fragile institutions where the population has been aging rapidly, and it is predicted to continue growing. Results from this study may assist policy makers and the healthcare community in further investigating frailty and its aspects, as frailty was demonstrated to be very common among older people in LAC.

Supporting Information

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors have no support or funding to report.

References

- 1.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(3):255–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(8):1487–92. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santos-Eggimann B, Cuénoud P, Spagnoli J, Junod J. Prevalence of frailty in middle-aged and older community-dwelling Europeans living in 10 countries. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(6):675–81. 10.1093/gerona/glp012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lally F, Crome P. Understanding frailty. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(975):16–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergman H, Ferrucci L, Guralnik J, Hogan DB, Hummel S, Karunananthan S, et al. Frailty: an emerging research and clinical paradigm—issues and controversies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):731–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gobbens RJ, van Assen MA, Luijkx KG, Wijnen-Sponselee MT, Schols JM. The Tilburg Frailty Indicator: psychometric properties. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11(5):344–55. 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitnitski AB, Mogilner AJ, Rockwood K. Accumulation of deficits as a proxy measure of aging. ScientificWorldJournal. 2001;1:323–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Theou O, Cann L, Blodgett J, Wallace LM, Brothers TD, Rockwood K. Modifications to the frailty phenotype criteria: Systematic review of the current literature and investigation of 262 frailty phenotypes in the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;21:78–94. 10.1016/j.arr.2015.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roppolo M, Mulasso A, Gobbens RJ, Mosso CO, Rabaglietti E. A comparison between uni- and multidimensional frailty measures: prevalence, functional status, and relationships with disability. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:1669–78. 10.2147/CIA.S92328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cesari M, Prince M, Thiyagarajan JA, De Carvalho IA, Bernabei R, Chan P, et al. Frailty: An Emerging Public Health Priority. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(3):188–92. 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palloni A, Mceniry M, Wong R, Pelaez M. The Elderly in Latin America and the Caribbean. Revista Galega de Economía. 2005;14:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palloni A, Pinto-Aguirre G, Peláez M. Demographic and health conditions of ageing in Latin America and the Caribbean. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31(4):762–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Runzer-Colmenares FM, Samper-Ternent R, Al Snih S, Ottenbacher KJ, Parodi JF, Wong R. Prevalence and factors associated with frailty among Peruvian older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;58(1):69–73. 10.1016/j.archger.2013.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guerra M, Prina AM, Ferri CP, Acosta D, Gallardo S, Huang Y, et al. A comparative cross-cultural study of the prevalence of late life depression in low and middle income countries. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:362–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prina AM, Acosta D, Acostas I, Guerra M, Huang Y, Jotheeswaran AT, et al. Cohort Profile: The 10/66 study. Int J Epidemiol. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Age-friendly primary health care centres toolkit: WHO; 2008. Available: http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/Age-Friendly-PHC-Centre-toolkitDec08.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):147–53. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munn Z, Moola S, Riitano D, Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(3):123–8. 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):39 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barendregt SAD, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brasil. Diretrizes Metodológicas: Elaboração de revisão sistemática e metanálise de estudos observacionais comparativos sobre fatores de risco e prognóstico Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodrigues CL, Ziegelmann PK. Metanálise: Um Guia Prático. Rev HCPA. 2010;30(4):436–47. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sterne JAC, Kirkwood BR. Essential Medical Statistics. 2Ed. ed2003.

- 27.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d4002 10.1136/bmj.d4002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alvarado BE, Zunzunegui MV, Béland F, Bamvita JM. Life course social and health conditions linked to frailty in Latin American older men and women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(12):1399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.At J, Bryce R, Prina M, Acosta D, Ferri CP, Guerra M, et al. Frailty and the prediction of dependence and mortality in low- and middle-income countries: a 10/66 population-based cohort study. BMC Med. 2015;13:138 10.1186/s12916-015-0378-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bollwein J, Diekmann R, Kaiser MJ. Mon does the mere risk of malnutrition increase the risk of frailty and an impaired physical performance in community-dwelling older adults? Clinical Nutrition 2011;6(1):128–9. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calado LB, Melo MP, Ferriolli E, Moriguti JC, Nereida KC. Blood pressure and the frailty syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2013;15. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duarte MCS, Fernandes MGM, Rodrigues PRA, Nóbrega MML. Prevalence and sociodemographic factors associated with frailty in elderly women. Rev bras enferm. 2013;66(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferrer A, Badia T, Formiga F, Sanz H, Megido MJ, Pujol R, et al. Frailty in the oldest old: prevalence and associated factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):294–6. 10.1111/jgs.12154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galbán PA, Soberats FJS, Navarro AMD, García MC. Diagnosis of frailty in urban community-dwelling older adults. Rev Cubana Salud Pública. 2009;35(2). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Díaz de León González E, Gutiérrez Hermosillo H, Martinez Beltran JA, Chavez JH, Palacios Corona R, Salinas Garza DP, et al. Validation of the FRAIL scale in Mexican elderly: results from the Mexican Health and Aging Study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ilhan B, Bahat Ozturk G, Kilic C, Tufan A, Aykin S, Muratli S, et al. Frequency of frailty syndrome in elders older than 75 years of age according to the frail criteria. European Geriatric Medicine. 2014;5(1):126–7. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreira VG, Lourenço RA. Prevalence and factors associated with frailty in an older population from the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: the FIBRA-RJ Study. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2013;68(7):979–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roppolo M, Mulasso A, Gobbens RJ, Mosso CO, Rabaglietti E. A comparison between uni- and multidimensional frailty measures: prevalence, functional status, and relationships with disability. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:1669–78. 10.2147/CIA.S92328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosero-Bixby L. The exceptionally high life expectancy of Costa Rican nonagenarians. Demography. 2008;45(3):673–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sánchez-García S, Sánchez-Arenas R, García-Peña C, Rosas-Carrasco O, Avila-Funes JA, Ruiz-Arregui L, et al. Frailty among community-dwelling elderly Mexican people: prevalence and association with sociodemographic characteristics, health state and the use of health services. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14(2):395–402. 10.1111/ggi.12114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sansó ea. polypharmacy: The most prevalent frailty criteria in the elderly. VacciMonitor. 2010;19. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sternberg EA. Osteoporosis and frailty. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valdiglesias V, Bonassi S, Dell'Armi V, Settanni S, Celi M, Mastropaolo S, et al. Micronucleus frequency in peripheral blood lymphocytes and frailty status in elderly. A lack of association with clinical features. Mutat Res. 2015;780:47–54. 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2015.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valcárcel EA. Association between elderly frailty and consumption of a varied diet. Correo Científico Médico De Holguín. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 46.St John PD, Tyas SL, Montgomery PR. Life satisfaction and frailty in community-based older adults: cross-sectional and prospective analyses. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(10):1709–16. 10.1017/S1041610213000902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simone PM, Haas AL. Frailty, Leisure Activity and Functional Status in Older Adults: Relationship With Subjective Well Being. Clinical Gerontologist 2013;36(4). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amaral FLJS, Guerra RO, Nascimento AFF, Maciel ACC. Social support and the frailty syndrome among elderly residents in the community. [PubMed]

- 49.Theou O, Mitnitski AB, Rockwood K. Prevalence of frailty across countries: is it related to national economic status?. The Gerontological Society of America. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Erusalimsky JD, Grillari J, Grune T, Jansen-Duerr P, Lippi G, Sinclair AJ, et al. In Search of 'Omics'-Based Biomarkers to Predict Risk of Frailty and Its Consequences in Older Individuals: The FRAILOMIC Initiative. Gerontology. 2016;62(2):182–90. 10.1159/000435853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kulmala J, Nykänen I, Hartikainen S. Frailty as a predictor of all-cause mortality in older men and women. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14(4):899–905. 10.1111/ggi.12190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jürschik P, Botigué T, Nuin C, Lavedán A. Association between Mini Nutritional Assessment and the Fried frailty index in older people living in the community. Med Clin (Barc). 2014;143(5):191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramos CGEL. Frailty and risk associations in older adults from an urban community. Revista Cubana de Medicina Militar. 2013;42(3). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garre-Olmo J, Calvó-Perxas L, López-Pousa S, de Gracia Blanco M, Vilalta-Franch J. Prevalence of frailty phenotypes and risk of mortality in a community-dwelling elderly cohort. Age Ageing. 2013;42(1):46–51. 10.1093/ageing/afs047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barbosa EA. Avaliação dos fatores de risco cardiovasculares com ênfase na pressão arterial, na síndrome da fragilidade em idosos. 2013.

- 56.Salmito M. Associação entre equilíbrio, marcha e síndrome da fragilidade em idosos residentes em área urbana. 2012.

- 57.Maia FdOM. Vulnerabilidade e envelhecimento: panorama dos idosos residentes no município de São Paulo—Estudo SABE. 2015.

- 58.Carvalho EMS. Associação entre postura corporal e fragilidade em idosos residentes em área urbana. 2012.

- 59.Pegorari MS, Ruas G, Patrizzi LJ. Relationship between frailty and respiratory function in the community-dwelling elderly. Braz J Phys Ther. 2013;17(1):9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Quevedo-Tejero EDC, Zavala-González MA, Alonso-Benites JR. Síndrome de fragilidad en adultos mayores no institucionalizados de Emiliano Zapata, Tabasco, México. Univ Méd Bogotá (Colombia). 2011;52(3):255–68. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Santiago LM. Fragilidade em idosos no Brasil: identificação e análise de um instrumento de avaliação para ser utilizado na população do país 2013.

- 62.Wong YY, Almeida OP, McCaul KA, Yeap BB, Hankey GJ, Flicker L. Homocysteine, frailty, and all-cause mortality in older men: the health in men study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(5):590–8. 10.1093/gerona/gls211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alexandre TaS, Corona LP, Nunes DP, Santos JL, Duarte YA, Lebrão ML. Similarities among factors associated with components of frailty in elderly: SABE Study. J Aging Health. 2014;26(3):441–57. 10.1177/0898264313519818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Llibre JeJ, López AM, Valhuerdi A, Guerra M, Llibre-Guerra JJ, Sánchez YY, et al. Frailty, dependency and mortality predictors in a cohort of Cuban older adults, 2003–2011. MEDICC Rev. 2014;16(1):24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Manrique-Espinoza bS-R, Snyder A, Moreno-Tamayo NS, Gutiérrez-Robledo LM, Avila-Funes J.A. Frailty and Social Vulnerability in Mexican Deprived and Rural Settings. Journal of agin and Health. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aguilar-Navarro S, Gutiérrez-Robledo LM, García-Lara JM, Payette H, Amieva H, Ávila-Funes JA, et al. The phenotype of frailty predicts disability and mortality among Mexican community-dwelling elderly. J Frailty Aging. 2012;1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.DA Silva Coqueiro R, DE Queiroz BM, Oliveira DS, DAS Merces MC, Carneiro JA, Pereira R, et al. Cross-sectional relationships between sedentary behavior and frailty in older adults. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Papiol M, Serra-Prat M, Vico J, Jerez N, Salvador N, Garcia M, et al. Poor Muscle Strength and Low Physical Activity are the Most Prevalent Frailty Components in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lanziotti Azevedo da Silva S, Campos Cavalcanti Maciel Á, de Sousa Máximo Pereira L, Domingues Dias JM, Guimarães de Assis M, Corrêa Dias R. Transition Patterns of Frailty Syndrome in Comunity-Dwelling Elderly Individuals: A Longitudinal Study. J Frailty Aging. 2015;4(2):50–5. 10.14283/jfa.2015.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Avila-Funes JA, Medina-Campos RH, Tamez-Rivera O, Navarrete-Reyes AP, Amieva H, Aguilar-Navarro S. Frailty Is Associated with Disability and Recent Hospitalization in Community-Dwelling Elderly: The Coyoacan Cohort. J Frailty Aging. 2014;3(4):206–10. 10.14283/jfa.2014.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Avila-Funes JA, Paniagua-Santos DL, Escobar-Rivera V, Navarrete-Reyes AP, Aguilar-Navarro S, Amieva H. Association between employee benefits and frailty in community-dwelling older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16(5):606–11. 10.1111/ggi.12523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fattori A, Santimaria MR, Alves RM, Guariento ME, Neri AL. Influence of blood pressure profile on frailty phenotype in community-dwelling elders in Brazil—FIBRA study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;56(2):343–9. 10.1016/j.archger.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.González-Pichardo AM, Navarrete-Reyes AP, Adame-Encarnación H, Aguilar-Navarro S, García-Lara JM, Amieva H, et al. Association between Self-Reported Health Status and Frailty in Community-Dwelling Elderly. J Frailty Aging. 2014;3(2):104–8. 10.14283/jfa.2014.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Macuco CR, Batistoni SS, Lopes A, Cachioni M, da Silva Falcão DV, Neri AL, et al. Mini-Mental State Examination performance in frail, pre-frail, and non-frail community dwelling older adults in Ermelino Matarazzo, São Paulo, Brazil. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(11):1725–31. 10.1017/S1041610212000907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pérez-Suárez TG, Gutiéres-Robledo LM, Alberto J, Acosta JL, Escamilla-Tich M, Ramón J, et al. VNTR polymorphisms of the IL-4 abd IL-1RN genes and their relationship with frailty syndrome in Mexican community-dwelling elderly. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sánchez-García EA. Frailty in Mexican community-dwelling elderly. 2011.

- 77.Silva JC, Moraes ZV, Silva C, Mazon SeB, Guariento ME, Neri AL, et al. Understanding red blood cell parameters in the context of the frailty phenotype: interpretations of the FIBRA (Frailty in Brazilian Seniors) study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59(3):636–41. 10.1016/j.archger.2014.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Silva DD, Held RB, Torres SV, Sousa MaL, Neri AL, Antunes JL. Self-perceived oral health and associated factors among the elderly in Campinas, Southeastern Brazil, 2008–2009. Rev Saude Publica. 2011;45(6):1145–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fohn EA. Frailty syndrome related to disability in the elderly. Acta paulista de enfermagem. 2012;25. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Silva SLA, Viana JUV, Silva VG, Dias JMD, Pereira LSM, Dias RC. Influence of Frailty and Falls on Functional Capacity and Gait in Community-Dwelling Elderly Individuals. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 2012;28(2):128–34. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Santos AA, Ceolim MF, Pavarini SCI, Neri AL, Rampazo MK. Associação entre transtornos do sono e níveis de fragilidade entre idosos. Acta paul enferm. 2014;27(2). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nunes D. Validação da avaliação subjetiva de gragilidade em idosos no município de São Paulo: Estudo Sabe (Saúde,bem estar e envelhecimento). 2011.

- 83.Arroyo N. Fatores associados a desempenho funcional autorrelatado: dados do projeto FIBRA—POLÓ UNICAMP. 2012.

- 84.Silva A. A influência de hábitos de vida (tabagismo, consumo nocivo de álcool e sedentarismo) associados à hipertensão arterial sistêmica na síndrome da fragilidade no idoso. 2012.

- 85.Moraes ZV. Estudo da síndrome de fragilidade em idosos residentes na comunidade e sua associação com parâmetros hematológicos. 2011.

- 86.Panes V. Adaptação dos componentes da síndrome de fragilidade e avaliação da fragilização dos idosos residentes no município de São Paulo:Estudo de sabe (Saúde, bem estar e envelhecimento). 2010.

- 87.Moretto M. Estado nutricional, adiposidade abdominal e síndrome da fragilidade em idosos da comunidade: Dados do estudo FIBRA—PÓLO UNICAMP. 2012.

- 88.Ebert N. Doenças crônicas, fragilidade e características emocionais de idosos comunitários: Estudo FIBRA IVOTI/RS. 2012.

- 89.Montes JFG, Borrero CLC, Henao GM. Fragilidade en Ancinos Colombianos. RevMedicaSanitas. 2012;15 (4):8–16. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Santos A. Perfil dos idosos que cochilam. Rev esc enferm USP. 2013;47:1345–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Santos A. Sono fragilidade e cognição estudo multicêntrico com idosos brasileiros. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem. 2013;66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Santos AA, Ceolim MF, Pavarini SCI, Neri AL, Rampazo MK. Associação entre transtornos do sono e níveis de fragilidade entre idosos. Acta paul enferm. 2014;27(2). [Google Scholar]

- 93.Varela-Pinedo L, Ortiz-Saavedra P, Chávez-Jimeno H. Frailty syndrome in community elderly people of Lima Metropolitana. Revista de la Sociedad Peruana de Medicina Interna. 2008;14. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Aguilar-Navarro SG, Amieva H, Gutiérrez-Robledo LM, Avila-Funes JA. Frailty among Mexican community-dwelling elderly: a story told 11 years later. The Mexican Health and Aging Study. Salud Publica Mex. 2015;57 Suppl 1:S62–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Andrade FB, Lebrão ML, Santos JL, Duarte YA. Relationship between oral health and frailty in community-dwelling elderly individuals in Brazil. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(5):809–14. 10.1111/jgs.12221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Corona LP, Andrade FCD, Duarte YAO, Lebrao ML. The relationship between anemia hemoglobin concentration and frailty in Brazilian older adults. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2015;19(9):935–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Curcio CL, Henao GM, Gomez F. Frailty among rural elderly adults. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:2 10.1186/1471-2318-14-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fohn EA. Frailty syndrome related to disability in the elderly. Acta paulista de enfermagem. 2012;25. [Google Scholar]

- 99.García-Peña C, Ávila-Funes JA, Dent E, Gutiérrez-Robledo L, Pérez-Zepeda M. Frailty prevalence and associated factors in the Mexican health and aging study: A comparison of the frailty index and the phenotype. Exp Gerontol. 2016;79:55–60. 10.1016/j.exger.2016.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Reis Júnior WMR, Carneiro JAO, Coqueiro RS, Santos KT, Fernandes MH. Pre-frailty and frailty of elderly residents in a municipality with a low Human Development Index. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem 2014;22(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Neri AL, Yassuda MS, Araújo LF, Eulálio MoC, Cabral BE, Siqueira ME, et al. [Methodology and social, demographic, cognitive, and frailty profiles of community-dwelling elderly from seven Brazilian cities: the FIBRA Study]. Cad Saude Publica. 2013;29(4):778–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ocampo-Chaparro JM, Zapata-Ossa HeJ, Cubides-Munévar AM, Curcio CL, Villegas JeD, Reyes-Ortiz CA. Prevalence of poor self-rated health and associated risk factors among older adults in Cali, Colombia. Colomb Med (Cali). 2013;44(4):224–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pegorari MS, Tavares DMS. Factors associated with the frailty syndrome in elderly individuals living in the urban area. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem 2014;22(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pinedo LV, Saavedra PJO, Jimeno HC. Velocidad de la marcha como indicador de fragilidad en adultos mayores de la comunidad en Lima, Perú. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología. 2010;45(1):22–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ramos GCF, Carneiro JA,Barbosa ATF, Mendonça JMG, Caldeira AP. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and associated factors among elderly in northern Minas Gerais: a population-based study. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria. 2015;64(2). [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ricci NA, Pessoa GS, Ferriolli E, Dias RC, Perracini MR. Frailty and cardiovascular risk in community-dwelling elderly: a population-based study. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1677–85. 10.2147/CIA.S68642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rosero-Bixby L, Dow WH. Surprising SES Gradients in mortality, health, and biomarkers in a Latin American population of adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64(1):105–17. 10.1093/geronb/gbn004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ruiz-Arregui L, Ávila-Funes JA, Amieva H, Borges- Yáñez SA, Villa-Romero A, Aguilar-Navarro S, et al. The Coyoacán cohort study: design, methodology and participant characteristics of a Mexican study on nutritional and psychosocial markers of frailty. 2013:1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Samper-Terent R, Reyes-Ortiz C, Ottenhancher KJ, Cano AC. Frailty and sarcopenia in Bogotá: results from the SABE Bogotá Study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sousa AC, Dias RC, Maciel Á, Guerra RO. Frailty syndrome and associated factors in community-dwelling elderly in Northeast Brazil. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(2):e95–e101. 10.1016/j.archger.2011.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tribess S, Júnior JSV, Oliveira RJ. Atividade física como preditor da ausência de fragilidade em idosos. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2012;58(3):341–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Vieira RA, Guerra RO, Giacomin KC, Vasconcelos KSS, Andrade ACS, Pereira LCM, et al. Prevalence of frailty and associated factors in community-dwelling elderly in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais State, Brazil: data from the FIBRA study Cad Saúde Pública. 2013;8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 113.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yamada M, Arai H. Predictive Value of Frailty Scores for Healthy Life Expectancy in Community-Dwelling Older Japanese Adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(11):1002.e7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Nguyen TN, Cumming RG, Hilmer SN. A Review of Frailty in Developing Countries. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19(9):941–6. 10.1007/s12603-015-0503-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Harttgen K, Kowal P, Strulik H, Chatterji S, Vollmer S. Patterns of frailty in older adults: comparing results from higher and lower income countries using the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) and the Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health (SAGE). PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e75847 10.1371/journal.pone.0075847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Puts MT, Lips P, Deeg DJ. Sex differences in the risk of frailty for mortality independent of disability and chronic diseases. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(1):40–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mitnitski A, Song X, Skoog I, Broe GA, Cox JL, Grunfeld E, et al. Relative fitness and frailty of elderly men and women in developed countries and their relationship with mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2184–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Shamliyan T, Talley KM, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL. Association of frailty with survival: a systematic literature review. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(2):719–36. 10.1016/j.arr.2012.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hubbard RE, Rockwood K. Frailty in older women. Maturitas. 2011;69(3):203–7. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Romero-Ortuno R, Fouweather T, Jagger C. Cross-national disparities in sex differences in life expectancy with and without frailty. Age Ageing. 2014;43(2):222–8. 10.1093/ageing/aft115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.