Abstract

Purpose

Accumulating studies have investigated the prognostic and clinical significance of programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) expression in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC); however, the results were conflicting and inconclusive. We conducted a meta-analysis to combine controversial data to precisely evaluate this issue.

Methods

Relevant studies were thoroughly searched on PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase until April 2016. Eligible studies were evaluated by selection criteria. Hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to estimate the prognostic role of PD-L1 for overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS)/recurrence-free survival (RFS). Odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI were selected to assess the relationship between PD-L1 and clinicopathological features of HCC patients. Publication bias was tested using Begg’s funnel plot.

Results

A total of seven studies published from 2009 to 2016 were included for meta-analysis. The data showed that high PD-L1 expression was correlated to shorter OS (HR =2.09, 95% CI: 1.66–2.64, P<0.001) as well as poor DFS/RFS (HR =2.3, 95% CI: 1.46–3.62, P<0.001). In addition, increased PD-L1 expression was also associated with tumor differentiation (HR =1.51, 95% CI: 1–2.29, P=0.05), vascular invasion (HR =2.16, 95% CI: 1.43–3.27, P<0.001), and α-fetoprotein (AFP; HR =1.46, 95% CI: 1–2.14, P=0.05), but had no association with tumor stage, tumor size, hepatitis history, sex, age, or tumor multiplicity. No publication bias was found for all analyses.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis revealed that overexpression of PD-L1 was predictive for shortened OS and DFS/RFS in HCC. Furthermore, increased PD-L1 expression was associated with less differentiation, vascular invasion, and AFP elevation.

Keywords: programmed death ligand-1, hepatocellular carcinoma, prognosis, meta-analysis

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the main form of liver malignancy as well as the fifth most prevalent neoplasm and the third most common cause of cancer death worldwide.1,2 In developing countries, HCC represents a much heavier health care burden, especially for males.1 Hepatitis B or C virus (HBV or HCV) infection is a major cause of HCC; in addition, HBV/HCV-infected cohorts have a significantly increased risk of HCC incidence compared with HBV/HCV-negative cohorts.3,4 Growing evidence indicates that the chronic inflammation caused by virus infection plays an important role in HCC development.5 Persistent expression of various cytokines in the process of chronic inflammation and recruitment of immune cells to tumor milieu confer an immunosuppressive microenvironment in the liver, which in turn promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis.6–8

Recent attention had been attracted by a series of molecules named “immune inhibitory checkpoints,” such as programmed death 1 (PD-1) and programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1).9 PD-L1, also known as B7 homologue 1 (B7-H1), is one of the ligands of PD-1. PD-1 belongs to B7-CD28 superfamily and is mainly expressed on the surface of T-, B-, and NK cells,10 whereas PD-L1 is known to be expressed on different malignant tumor cells and a variety of other conventional immune cells.11 The combination and interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1 deliver negative costimulatory signals and thus protect tumor cells from immune attacks.12 Overexpression of PD-L1 has been reported to be linked with worse prognosis in various cancer types, including non-small-cell lung cancer,13 renal cell carcinoma,14 gastric carcinoma,15 brain tumors,16 and breast cancer.17 Different research groups have investigated the prognostic role of PD-L1 expression in HCC;18–24 however, the results were inconclusive. Some studies18–20 showed that upregulated PD-L1 expression predicted poor survival in HCC, whereas other reports22,24 presented negative results. Therefore, there is a need to combine the conflicting data to have an explicit clarification. In this study, we employed a meta-analysis and collected results from eligible studies to explore prognostic value of PD-L1 expression for HCC patients; furthermore, the relationship between PD-L1 expression and clinicopathological features in HCC was also evaluated.

Materials and methods

PRISMA guidelines

This meta-analysis was performed in accordance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines,25 and the PRISMA checklist is presented in Table S1.

Literature search

The electronic databases of Embase, Web of Science, and PubMed were comprehensively searched (up to April 2016). The search terms were: “hepatocellular carcinoma” (MeSH terms), “hepatocellular cancer,” “HCC,” “liver cancer,” “programmed cell death-ligand 1,” “PD-L1,” “B7 homolog 1,” “B7-H1,” “cluster of differentiation 274,” and “CD274.” References from retrieved articles were also screened for potential studies.

Study selection

To be included studies had to meet the following criteria: 1) HCC was histopathologically diagnosed; 2) the expression of PD-L1 was determined by immunohistochemistry (IHC) or other methods; 3) data concerning the relationships between PD-L1 and survival including overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS)/recurrence-free survival (RFS) and/or clinical features in HCC was reported or could be computed according to Tierney’s method;26 4) patients were stratified in two categories classified as PD-L1 positive (high) or PD-L1 negative (low); 5) published as full-text articles; and 6) published in English. The following articles were excluded: 1) meeting abstracts, reviews, case reports, or letters; 2) nonhuman studies; and 3) absence of necessary data for hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) or odds ratio (OD) and 95% CI estimation.

Data extraction

Two investigators (XB Gu and XS Gao) independently extracted the following information from included studies: first author’s name, year of publication, country, histological type, tumor stage, differentiation, treatment methods, sample size, detection approach for PD-L1, and HRs and 95% CIs for OS, DFS, and RFS, if provided. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were settled by discussion.

Statistical analysis

HR with 95% CI was utilized to evaluate the association between elevated PD-L1 expression and OS, DFS, and RFS. If the data were not directly provided in text, then they were calculated from the survival curves by Tierney’s method.26 OR with 95% CI were calculated to assess the effects of PD-L1 expression on clinicopathological features. Heterogeneity was examined by using Q and I2 test. If I2.50% or Ph<0.1, which indicated significant heterogeneity, a random-effects model was used; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was adopted. Potential risk of publication bias was estimated using Begg’s funnel plot. All analyses were performed using Stata version12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). P-value <0.05 indicates statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of included publications

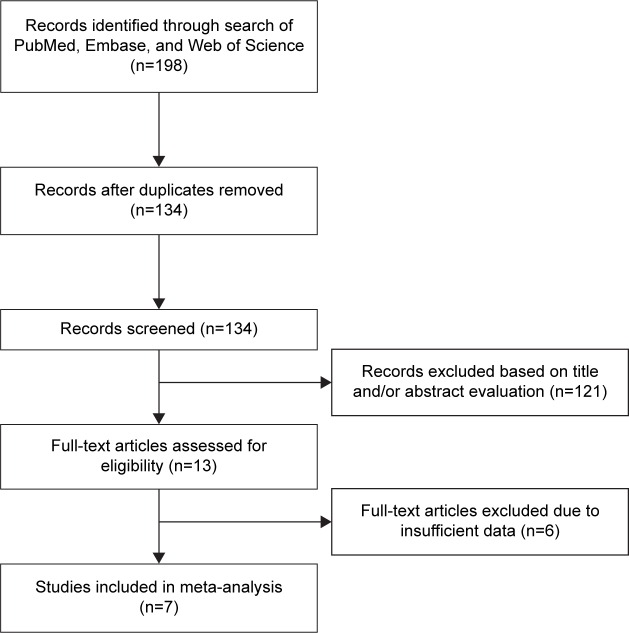

Through initial database searching, 198 records were identified. After removing duplicates, 134 records were screened for eligibility by title/abstract reading; then, 121 articles were discarded because they were carried out in animals, were irrelevant, or were not published in English (one was in Chinese and one was in Polish), or a combination of them. Subsequently, 13 records were left for eligibility evaluation. Thereafter, six records were excluded due to insufficient data for HR and 95% CI and OR and 95% CI calculation. Finally, seven studies18–24 published from 2009 to 2016 were included in this meta-analysis. The literature confirmation process is shown in Figure 1. The total sample size of seven studies was 901, ranging from 58 to 240. Five studies18–22 were conducted in Asian countries and two studies23,24 were performed in Western countries. The detailed information of the included studies is depicted in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing literature filtration process.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of eligible studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Year | Country | Histological type | Stage | Patients (n) | Treatment | Detection method | PD-L1 + n (%) | Survival analysis | HR and 95% CI estimation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gao et al18 | 2009 | People’s Republic of China | HCC | I–III | 240 | Surgery | IHC | 60 (25) | OS, DFS, CSS | HR and 95% CI |

| Wu et al19 | 2009 | People’s Republic of China | HCC | I–IV | 71 | Surgery | IHC | 35 (49.3) | OS | Survival curves |

| Zeng et al20 | 2011 | People’s Republic of China | HCC | A–Ba | 109 | Cryoablation | IHC | 47 (43.1) | OS, DFS | HR and 95% CI |

| Kan and Dong21 | 2015 | People’s Republic of China | HCC | I–IV | 128 | Surgery | IHC | 105 (82) | OS | HR and 95% CI |

| Umemoto et al22 | 2015 | Japan | HCC | I–IV | 80 | Surgery | IHC | 43 (53.8) | OS, RFS | HR and 95% CI |

| Finkelmeier et al23 | 2016 | Germany | HCC | A–Da | 215 | Mixed | ELISA | 63 (29.3) | OS | HR and 95% CI |

| Gabrielson et al24 | 2016 | United States | HCC | I–IV | 58 | Surgery | IHC | 19 (32.8) | OS, RFS | Survival curves |

Note:

BCLC staging.

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; IHC, immunohistochemical staining; PD-L1+, programmed death ligand-1 positive; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival; CSS, cancer-specific survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer.

Prognostic role of PD-L1 expression for OS and DFS/RFS

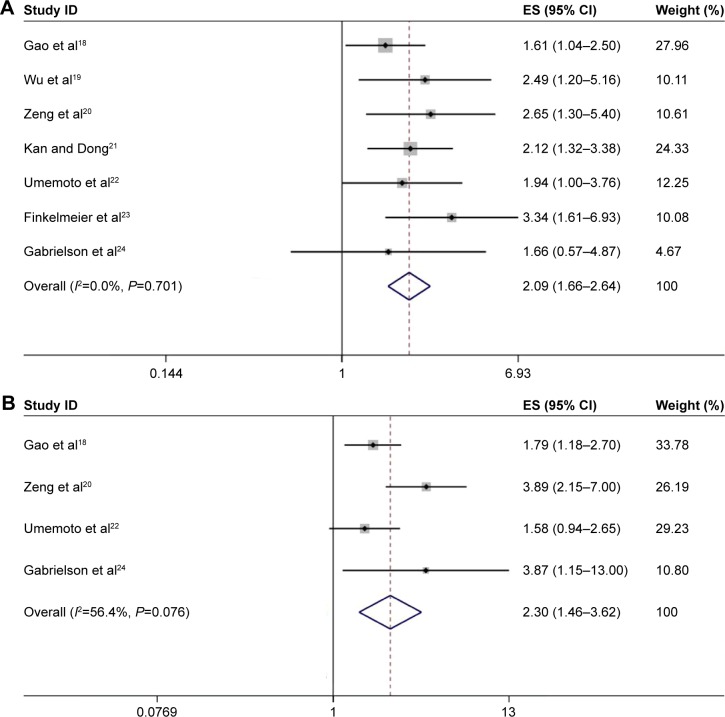

All of the seven studies18–24 (comprising 901 patients) investigated the association between PD-L1 expression and OS in HCC. The pooled HR was 2.09, with 95% CI: 1.66–2.64, P<0.001; in addition, there was no heterogeneity (I2=0, Ph=0.701; Figure 2). For DFS/RFS, there were four studies with 487 patients that explored the correlation. The combined HR and 95% CI were: HR =2.3, 95% CI: 1.46–3.62, P<0.001, although with heterogeneity (I2=56.4%, Ph=0.076; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forrest plot of HRs for the association of PD-L1 expression with (A) OS and (B) DFS/RFS in HCC patients.

Note: Weights are from random effects analysis.

Abbreviations: HRs, hazard ratios; OS, overall survival; PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1; DFS, disease-free survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size.

Association between PD-L1 expression and clinicalpathological factors

ORs and 95% CIs were calculated to evaluate the association between PD-L1 expression and clinicopathological factors, including age, sex, tumor stage, tumor differentiation, tumor size, vascular invasion, hepatitis history, α-fetoprotein (AFP), and tumor multiplicity. At least three studies were included for analysis of each parameter. As listed in Table 2, the results demonstrated that PD-L1 overexpression was correlated with poor tumor differentiation (HR =1.51, 95% CI: 1–2.29, P=0.05; I2=31.7%, Ph=0.222), vascular invasion (HR =2.16, 95% CI: 1.43–3.27, P<0.001; I2=42.3%, Ph=0.158), and AFP (HR =1.46, 95% CI: 1–2.14, P=0.05; I2=0, Ph=0.527). However, there was no association between PD-L1 expression and tumor stage, tumor size, hepatitis history, sex, age, or tumor multiplicity.

Table 2.

Association between PD-L1 expression and clinical features of HCC patients in meta-analysis

| Factors | Studies (n) | Patients (n) | Analytical model | OR (95% CI) | P-value | Heterogeneity

|

Publication bias Begg’s P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 (%) | Ph | |||||||

| Tumor stage (III–IV vs I–II) | 5 | 615 | REM | 1.13 (0.47–2.74) | 0.784 | 73.5 | 0.005 | 0.806 |

| Tumor differentiation (poor vs moderate/high) | 4 | 506 | FEM | 1.51 (1–2.29) | 0.05 | 31.7 | 0.222 | 0.734 |

| Vascular invasion (yes vs no) | 4 | 487 | FEM | 2.16 (1.43–3.27) | ,0.001 | 42.3 | 0.158 | 0.497 |

| Tumor size (>5 cm vs <5 cm) | 4 | 557 | REM | 1.66 (0.6–4.57) | 0.329 | 82.9 | 0.001 | 0.734 |

| Hepatitis history (yes vs no) | 4 | 557 | REM | 1.8 (0.8–4.08) | 0.158 | 61.5 | 0.05 | 1 |

| AFP (>20 ng/mL vs <20 ng/mL) | 4 | 557 | FEM | 1.46 (1–2.14) | 0.05 | 0 | 0.527 | 1 |

| Sex (male vs female) | 4 | 557 | FEM | 0.95 (0.59–1.53) | 0.833 | 0 | 0.534 | 1 |

| Age (>median vs <median) | 3 | 477 | FEM | 0.82 (0.55–1.22) | 0.329 | 0 | 0.876 | 1 |

| Tumor multiplicity (multiplicity vs single) | 3 | 429 | FEM | 1.23 (0.8–1.89) | 0.338 | 0 | 0.715 | 1 |

Notes: P-values were obtained by using the ‘metan’ programm in STATA V.12.0. P-value<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Abbreviations: PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1; FEM, fixed-effects model; REM, random-effects model; AFP, α-fetoprotein; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

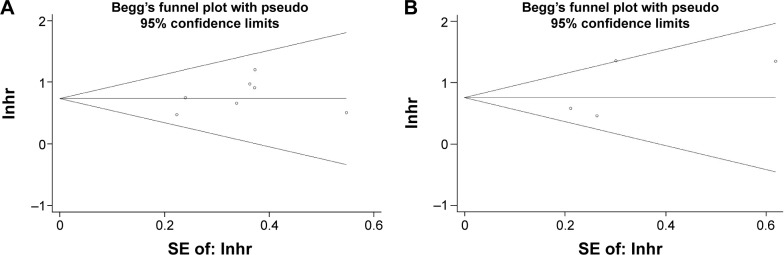

Publication bias

Begg’s funnel plot was utilized to test potential publication bias. The results showed that there was no publication bias for OS or DFS/RFS analysis (Begg’s test: P=0.368 for OS and P=0.734 for DFS/RFS; Figure 3). Moreover, there was no publication bias for the analysis of clinicopathological features (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Begg’s funnel plot for publication bias tests in (A) OS and (B) DFS/RFS in HCC.

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; SE, standard error; lnhr, natural logarithm of hazard ratio.

Discussion

A number of studies have investigated the clinical significance of PD-L1 expression in patients with HCC, but the results were inconclusive. In this study, we collected data from seven eligible studies and assessed the prognostic and clinical value of PD-L1 for HCC. Our results showed that high PD-L1 expression predicted poor OS and DFS/RFS in HCC; in addition, high PD-L1 expression was associated with tumor differentiation, vascular invasion, and AFP. The results suggested that PD-L1 expression had diagnostic value for poor differentiation and neovascularization; meanwhile, it provided implications for shortened survival to stratify risk patients. To our knowledge, this was the first meta-analysis exploring both the prognostic and clinical value of PD-L1 expression for HCC patients as an individual study.

PD-1 and its two ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 could combine to limit the activity of peripheral T-cells in chronic inflammation and autoimmunity.10,27–29 The PD-1/PD-1 ligand system is an intrinsic mechanism in physiological conditions that maintains balance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory activity and protects our bodies from harmful adverse effects caused by immune responses. Unfortunately, this system is aberrantly activated in cancer patients and promotes tolerance to tumor antigens, resulting in immune suppression in the tumor microenvironment.30 At the same time, PD-1/PD-1 ligand system is also a promising target to activate antitumor immunity. Monoclonal antibodies targeting PD-1 and PD-L1 have showed encouraging effects and prolonged the stabilization of disease for a variety of cancer types, including melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer, and gastric cancer.31,32 In addition, PD-L1 expression was also explored as a prognostic biomarker for different cancers including HCC. PD-1 and PD-L1 interaction could render immune suppression in multiple ways such as suppressing T-cell activation, inducing CD8+ cell apoptosis, and recruiting immunosuppressive cells.33

Previous studies have investigated the prognostic value of PD-L1 in various solid tumors including non-small-cell lung cancer,13 gastric carcinoma,15 and breast cancer.17 Our results showed that elevated PD-L1 expression was correlated with poor survival, which was in accordance with the findings in other cancers.13,14,34,35 Furthermore, we also investigated the clinical significance of PD-L1 expression, through which we found that PD-L1 was correlated with poor differentiation, vascular invasion, and AFP. The cancer immunoediting theory suggested that an immunosuppressive environment had already existed during the initiation of tumor occurrence;30 therefore, PD-L1 was likely to be expressed in poorly differentiated HCC. Additionally, evidence showed that VEGF overexpression could promote accumulation of immunosuppressive cells, which may further induce PD-L1 expression.36 We have noticed that a few studies37–39 had investigated the prognostic role of PD-L1 in HCC using meta-analysis. However, these studies only enrolled HCC as a small part of their studies, along with other solid tumors. Each study only included two studies of HCC for analysis. Compared with these studies, our meta-analysis containing seven studies published up to 2016 was more comprehensive and timely. Therefore, our results are more reliable and persuasive.

Several limitations need to be pointed out. First, heterogeneity still existed for DFS/RFS analysis, which may be caused by different patient selection standards and different antibodies for IHC use. Second, in our meta-analysis, only articles published in English were included. In the literature selection process of this meta-analysis, two studies published in languages other than English were excluded, but one of them was an animal study and the other was an irrelevant study. So, these two studies would have been eliminated for other reasons besides language. Therefore, inclusion of English papers did not substantially introduce potential publication bias, as suggested by Begg’s test (all P-value >0.05 for publication bias tests). Third, six studies used IHC to detect PD-L1 expression, while one study selected the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method, which may cause slight heterogeneity. Therefore, further studies using uniform criteria are needed.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis revealed that high expression of PD-L1 was predictive for poor OS and DFS/RFS in HCC patients. Furthermore, high PD-L1 expression was associated with poor tumor differentiation, vascular invasion, and AFP elevation. Our results suggest that PD-L1 is an effective prognosis biomarker for HCC. However, because of limitations of this study, well-designed investigations using uniform criteria are warranted to verify our results.

Supplementary material

Table S1.

PRISMA checklist

| Section/topic | Number | Checklist item | Reported on page number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review, meta-analysis, or both. | 1 |

| Abstract | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary including, as applicable: background; objectives; data sources; study eligibility criteria, participants, and interventions; study appraisal and synthesis methods; results; limitations; conclusions and implications of key findings; systematic review registration number. | 2, 3 |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. | 4, 5 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of questions being addressed with reference to participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS). | 4, 5 |

| Methods | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate if a review protocol exists, if and where it can be accessed (eg, Web address), and, if available, provide registration information including registration number. | 5 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify study characteristics (eg, PICOS, length of follow-up) and report characteristics (eg, years considered, language, publication status) used as criteria for eligibility, giving rationale. | 5, 6 |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources (eg, databases with dates of coverage, contact with study authors to identify additional studies) in the search and date last searched. | 5 |

| Search | 8 | Present full electronic search strategy for at least one database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 5 |

| Study selection | 9 | State the process for selecting studies (ie, screening, eligibility, included in systematic review, and, if applicable, included in the meta-analysis). | 5, 6 |

| Data collection process | 10 | Describe method of data extraction from reports (eg, piloted forms, independently, in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 6 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought (eg, PICOS, funding sources) and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 6 |

| Risk of bias in individual studies | 12 | Describe methods used for assessing risk of bias of individual studies (including specification of whether this was done at the study or outcome level), and how this information is to be used in any data synthesis. | 6, 7 |

| Summary measures | 13 | State the principal summary measures (eg, risk ratio, difference in mean values). | 6, 7 |

| Synthesis of results | 14 | Describe the methods of handling data and combining results of studies, if done, including measures of consistency (eg, I2) for each meta-analysis. | 6, 7 |

| Risk of bias across studies | 15 | Specify any assessment of risk of bias that may affect the cumulative evidence (eg, publication bias, selective reporting within studies). | 6, 7 |

| Additional analyses | 16 | Describe methods of additional analyses (eg, sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression), if done, indicating which were pre-specified. | 6, 7 |

| Results | |||

| Study selection | 17 | Give numbers of studies screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally with a flow diagram. | 7 |

| Study characteristics | 18 | For each study, present characteristics for which data were extracted (eg, study size, PICOS, follow-up period) and provide the citations. | 7 |

| Risk of bias within studies | 19 | Present data on risk of bias of each study and, if available, any outcome level assessment (see item 12). | 8, 9 |

| Results of individual studies | 20 | For all outcomes considered (benefits or harms), present, for each study: (a) simple summary data for each intervention group, (b) effect estimates and confidence intervals, ideally with a forest plot. | 7, 8 |

| Synthesis of results | 21 | Present results of each meta-analysis done, including confidence intervals and measures of consistency. | 7, 8 |

| Risk of bias across studies | 22 | Present results of any assessment of risk of bias across studies (see Item 15). | 8, 9 |

| Additional analysis | 23 | Give results of additional analyses, if done (eg, sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression [see Item 16]). | 8 |

| Discussion | |||

| Summary of evidence | 24 | Summarize the main findings including the strength of evidence for each main outcome; consider their relevance to key groups (eg, health care providers, users, and policy makers). | 9, 10 |

| Limitations | 25 | Discuss limitations at study and outcome level (eg, risk of bias), and at review-level (eg, incomplete retrieval of identified research, reporting bias). | 11 |

| Conclusions | 26 | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence, and implications for future research. | 11 |

| Funding | |||

| Funding | 27 | Describe sources of funding for the systematic review and other support (eg, supply of data); role of funders for the systematic review. | 12 |

Notes: Reproduced from Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7): Epub July 2009.1 For more information, visit: www.prisma-statement.org.

Abbreviations: PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; PICOS, Participants, Intervention, Control, Outcome, Study design.

Reference

- 1.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. Epub July 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Clinical Features Research of Capital (number Z141107002514160).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2012;379(9822):1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(6):1264–1273. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodgame B, Shaheen NJ, Galanko J, El-Serag HB. The risk of end stage liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma among persons infected with hepatitis C virus: publication bias? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(11):2535–2542. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makarova-Rusher OV, Medina-Echeverz J, Duffy AG, Greten TF. The yin and yang of evasion and immune activation in HCC. J Hepatol. 2015;62(6):1420–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang A, Zhang B, Yan W, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells regulate immune response in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection through PD-1-induced IL-10. J Immunol. 2014;193(11):5461–5469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu D, Fu J, Jin L, et al. Circulating and liver resident CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells actively influence the antiviral immune response and disease progression in patients with hepatitis B. J Immunol. 2006;177(1):739–747. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuzaki K, Murata M, Yoshida K, et al. Chronic inflammation associated with hepatitis C virus infection perturbs hepatic transforming growth factor beta signaling, promoting cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2007;46(1):48–57. doi: 10.1002/hep.21672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kassel R, Cruise MW, Iezzoni JC, Taylor NA, Pruett TL, Hahn YS. Chronically inflamed livers up-regulate expression of inhibitory B7 family members. Hepatology. 2009;50(5):1625–1637. doi: 10.1002/hep.23173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpel AH. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Ann Rev Immunol. 2008;26:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Afreen S, Dermime S. The immunoinhibitory B7-H1 molecule as a potential target in cancer: killing many birds with one stone. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2014;7(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwai Y, Ishida M, Tanaka Y, Okazaki T, Honjo T, Minato N. Involvement of PD-L1 on tumor cells in the escape from host immune system and tumor immunotherapy by PD-L1 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(19):12293–12297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192461099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aguiar PN, Jr, Santoro IL, Tadokoro H, et al. The role of PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a network meta-analysis. Immunotherapy. 2016;8(4):479–488. doi: 10.2217/imt-2015-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iacovelli R, Nole F, Verri E, et al. Prognostic role of PD-L1 expression in renal cell carcinoma. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Target Oncol. 2016;11(2):143–148. doi: 10.1007/s11523-015-0392-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu C, Zhu Y, Jiang J, Zhao J, Zhang XG, Xu N. Immunohistochemical localization of programmed death-1 ligand-1 (PD-L1) in gastric carcinoma and its clinical significance. Acta Histochem. 2006;108(1):19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs JF, Idema AJ, Bol KF, et al. Regulatory T cells and the PD-L1/PD-1 pathway mediate immune suppression in malignant human brain tumors. Neurooncology. 2009;11(4):394–402. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghebeh H, Mohammed S, Al-Omair A, et al. The B7-H1 (PD-L1) T lymphocyte-inhibitory molecule is expressed in breast cancer patients with infiltrating ductal carcinoma: correlation with important high-risk prognostic factors. Neoplasia. 2006;8(3):190–198. doi: 10.1593/neo.05733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao Q, Wang XY, Qiu SJ, et al. Overexpression of PD-L1 significantly associates with tumor aggressiveness and postoperative recurrence in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(3):971–979. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu K, Kryczek I, Chen L, Zou W, Welling TH. Kupffer cell suppression of CD8+ T cells in human hepatocellular carcinoma is mediated by B7-H1/programmed death-1 interactions. Cancer Res. 2009;69(20):8067–8075. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng Z, Shi F, Zhou L, et al. Upregulation of circulating PD-L1/PD-1 is associated with poor post-cryoablation prognosis in patients with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. PloS One. 2011;6(9):e23621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kan G, Dong W. The expression of PD-L1 APE1 and P53 in hepatocellular carcinoma and its relationship to clinical pathology. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19(16):3063–3071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Umemoto Y, Okano S, Matsumoto Y, et al. Prognostic impact of programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 expression in human leukocyte antigen class I-positive hepatocellular carcinoma after curative hepatectomy. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50(1):65–75. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-0933-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finkelmeier F, Canli O, Tal A, et al. High levels of the soluble programmed death-ligand (sPD-L1) identify hepatocellular carcinoma patients with a poor prognosis. Eur J Cancer. 2016;59:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gabrielson A, Wu Y, Wang H, et al. Intratumoral CD3 and CD8 T-cell densities associated with relapse free survival in HCC. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4(5):419–430. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, et al. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature. 2006;439(7077):682–687. doi: 10.1038/nature04444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Latchman Y, Wood CR, Chernova T, et al. PD-L2 is a second ligand for PD-1 and inhibits T cell activation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(3):261–268. doi: 10.1038/85330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Targeting the PD-1/B7-H1 (PD-L1) pathway to activate anti-tumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(2):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331(6024):1565–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.1203486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQM, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Eng J Med. 2012;366(26):2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pauken KE, Wherry EJ. Overcoming T cell exhaustion in infection and cancer. Trends Immunol. 2015;36(4):265–276. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu F, Feng G, Zhao H, et al. Clinicopathologic significance and prognostic value of B7 homolog 1 in gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2015;94(43):e1911. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang B, Chen L, Bao C, et al. The expression status and prognostic significance of programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 in gastrointestinal tract cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:2617–2625. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S91025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terme M, Pernot S, Marcheteau E, et al. VEGFA-VEGFR pathway blockade inhibits tumor-induced regulatory T-cell proliferation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73(2):539–549. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin Z, Xu Y, Zhang Y, et al. The prevalence and clinicopathological features of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression: a pooled analysis of literatures. Oncotarget. 2016;79(12):15033–15046. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu P, Wu D, Li L, Chai Y, Huang J. PD-L1 and survival in solid tumors: a meta-analysis. PloS One. 2015;10(6):e0131403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin Y, Zhao J, Shi X, Yu X. Prognostic value of programed death ligand 1 in patients with solid tumors: a meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Therap. 2015;11(Suppl 1):C38–C43. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.163837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

PRISMA checklist

| Section/topic | Number | Checklist item | Reported on page number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review, meta-analysis, or both. | 1 |

| Abstract | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary including, as applicable: background; objectives; data sources; study eligibility criteria, participants, and interventions; study appraisal and synthesis methods; results; limitations; conclusions and implications of key findings; systematic review registration number. | 2, 3 |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. | 4, 5 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of questions being addressed with reference to participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS). | 4, 5 |

| Methods | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate if a review protocol exists, if and where it can be accessed (eg, Web address), and, if available, provide registration information including registration number. | 5 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify study characteristics (eg, PICOS, length of follow-up) and report characteristics (eg, years considered, language, publication status) used as criteria for eligibility, giving rationale. | 5, 6 |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources (eg, databases with dates of coverage, contact with study authors to identify additional studies) in the search and date last searched. | 5 |

| Search | 8 | Present full electronic search strategy for at least one database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 5 |

| Study selection | 9 | State the process for selecting studies (ie, screening, eligibility, included in systematic review, and, if applicable, included in the meta-analysis). | 5, 6 |

| Data collection process | 10 | Describe method of data extraction from reports (eg, piloted forms, independently, in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 6 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought (eg, PICOS, funding sources) and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 6 |

| Risk of bias in individual studies | 12 | Describe methods used for assessing risk of bias of individual studies (including specification of whether this was done at the study or outcome level), and how this information is to be used in any data synthesis. | 6, 7 |

| Summary measures | 13 | State the principal summary measures (eg, risk ratio, difference in mean values). | 6, 7 |

| Synthesis of results | 14 | Describe the methods of handling data and combining results of studies, if done, including measures of consistency (eg, I2) for each meta-analysis. | 6, 7 |

| Risk of bias across studies | 15 | Specify any assessment of risk of bias that may affect the cumulative evidence (eg, publication bias, selective reporting within studies). | 6, 7 |

| Additional analyses | 16 | Describe methods of additional analyses (eg, sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression), if done, indicating which were pre-specified. | 6, 7 |

| Results | |||

| Study selection | 17 | Give numbers of studies screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally with a flow diagram. | 7 |

| Study characteristics | 18 | For each study, present characteristics for which data were extracted (eg, study size, PICOS, follow-up period) and provide the citations. | 7 |

| Risk of bias within studies | 19 | Present data on risk of bias of each study and, if available, any outcome level assessment (see item 12). | 8, 9 |

| Results of individual studies | 20 | For all outcomes considered (benefits or harms), present, for each study: (a) simple summary data for each intervention group, (b) effect estimates and confidence intervals, ideally with a forest plot. | 7, 8 |

| Synthesis of results | 21 | Present results of each meta-analysis done, including confidence intervals and measures of consistency. | 7, 8 |

| Risk of bias across studies | 22 | Present results of any assessment of risk of bias across studies (see Item 15). | 8, 9 |

| Additional analysis | 23 | Give results of additional analyses, if done (eg, sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression [see Item 16]). | 8 |

| Discussion | |||

| Summary of evidence | 24 | Summarize the main findings including the strength of evidence for each main outcome; consider their relevance to key groups (eg, health care providers, users, and policy makers). | 9, 10 |

| Limitations | 25 | Discuss limitations at study and outcome level (eg, risk of bias), and at review-level (eg, incomplete retrieval of identified research, reporting bias). | 11 |

| Conclusions | 26 | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence, and implications for future research. | 11 |

| Funding | |||

| Funding | 27 | Describe sources of funding for the systematic review and other support (eg, supply of data); role of funders for the systematic review. | 12 |

Notes: Reproduced from Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7): Epub July 2009.1 For more information, visit: www.prisma-statement.org.

Abbreviations: PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; PICOS, Participants, Intervention, Control, Outcome, Study design.