Abstract

A 55-year-old man presented with oral mucosal ulcers, blackening of both hands, and hyperpigmentation on axillary, anal, and inguinal regions for the last 3 months, which were all progressive. The patient was referred to the oncology department with the diagnosis of acanthosis nigricans for investigation of an underlying malignancy. He was a smoker. A computed tomography scan of thorax revealed enlarged mediastinal lymphadenopathies and a lesion on the left upper lobe. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the mediastinal lesion was consistent with squamous cell carcinoma, and biopsies of the skin and oral mucosal lesion also further confirmed the diagnosis of acanthosis nigricans. After docetaxel and cisplatin chemotherapy, a significant improvement in his skin and mucosal lesions was observed with almost complete resolution of the pulmonary lesion and the mediastinal lymph nodes.

Keywords: acanthosis nigricans, squamous cell lung cancer, paraneoplastic syndrome

Introduction

A paraneoplastic syndrome is a clinical or laboratory manifestation due to cancer in the body, but instead of a mass effect it is due to the remote effect of cancer cells or immune reaction, and there might be no relation between the severity of paraneoplastic symptoms and signs and stage of the underlying cancer.1 The syndromes may be a result of secretion of peptides or hormones from the tumor cells or host response to the tumor.2 The paraneoplastic syndromes may be the initial sign of the tumor; therefore, early recognition may be important for the detection of cancer at earlier stages. Paraneoplastic syndrome may precede an undiagnosed cancer, months to years before clinical diagnosis. Paraneoplastic syndromes can be associated with many types of cancer.3 Acanthosis nigricans (AN) is one of the rare paraneoplastic syndromes associated with lung cancer.2 In most cases, AN reflects metabolic disturbances seen in patients with obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, or medications.2,4 The most common histologic cancer type associated with AN is adenocarcinoma, generally involving the gastrointestinal system (gastric adenocarcinoma).5 Less commonly, paraneoplastic AN is associated with non-small-cell lung cancer.6–8 AN is characterized by gray-brown hyperpigmented, velvety plaques that often affect the neck, flexor area, and anogenital regions.6 The malignant and benign forms are similar in appearance, but the malignant form progresses rapidly, and pruritus is common. Oral lesion, observed in 50% of cases, is generally located on the lips, tongue, and buccal mucosa.9 “Tripe palms” is also known as acanthosis palmaris. Patients show thickened palms with exaggerated hyperkeratotic ridges, Brown pigmentation, and a velvety texture. Tripe palms usually occur in patients with lung and gastric adenocarcinoma.8,10

The pathogenesis of AN is not clarified yet. One possible etiology is the interactions between increased levels of insulin with insulin-like growth factor receptors and their effect on keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts.11 In addition, tumoral paraneoplastic effect by secretion of tumor growth factor alpha leads to keratinocyte proliferation and the development of AN.7,8 Paraneoplastic symptoms may precede the diagnosis of malignancy or it may appear with other symptoms of the original tumor.5

Here, we present a case of AN as the first symptom preceding the diagnosis of squamous cell lung cancer.

Case report

A 55-year-old man patient was apparently well 1 year ago. After that, he noticed a gradual blackening of dorsum on both hands and face during one year (Figure 1). He was admitted to the hospital with hyperpigmentation on face, dorsum of hand, and anal, inguinal, and auxiliary regions and multiple oral mucosal ulcers consistent with AN. Therefore, an underlying malignancy was suspected. On systematic questioning, the patient told that he did not have any chronic diseases; there was no weight loss, dysphagia, hematemesis, melena, hemoptysis, or anemia. He is a heavy smoker with 50 pack-years of smoking. His familial history and physical examination showed no relevant findings. The patient had hyperpigmented, velvety skin lesions at the lower and upper extremities, face, palms, and around axillary, inguinal, and anal regions. He also had multiple mucosal oral ulcers and tripe palms. There were no palpable lymph nodes. The respiratory tract examination with auscultation was normal. The abdomen was soft with no hepatosplenomegaly. Other systemic examinations were within normal limits. The laboratory findings showed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate 15 mm/h, fasting blood glucose 79 mg/dL, and hemoglobin 13 g/dL. Tumor markers and other laboratory findings were within the normal range.

Figure 1.

Patient photos.

Notes: (A) Two years ago, normal skin color. (B) Before treatment. (C) After treatment.

His chest X-ray looked roughly normal, but during careful investigation of the hilar area, we noticed some minimal enlargement (Figure 2). The endoscopy of upper gastrointestinal tract and colonoscopy were normal. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the thorax was performed. The CT scan revealed mediastinal lymphadenopathies and a millimetric lesion on the left upper lobe (8 mm; Figure 3). We prescribed antibiotics for indolent infection and repeated the CT scan 1.5 months later. This CT scan of thorax showed us that the mediastinal lymphadenopathy still existed and was of the same size, but the left upper lobe millimetric lesion was enlarged to 10 mm. We performed an endobronchial ultrasound, and the cytological examination of mediastinal lymph node biopsy was reported to be consistent with squamous cell lung cancer (Figure 4). A positron emission tomography scan showed fludeoxyglucose involvement in the mediastinal lymph node (maximum standard uptake value 12) and left upper lung nodule (maximum standard uptake value 4). Subsequently, biopsy was taken from the skin and mucosal lesion. These biopsies confirmed to be consistent with AN (Figure 5).

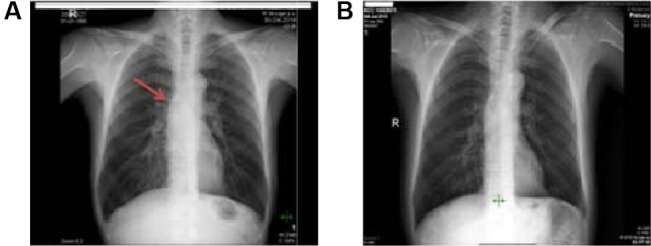

Figure 2.

The patient’s chest X-ray.

Notes: (A) Before treatment, nearly normal. (B) After treatment. The arrow represents the minimal enlargement of mediastinal lymph node.

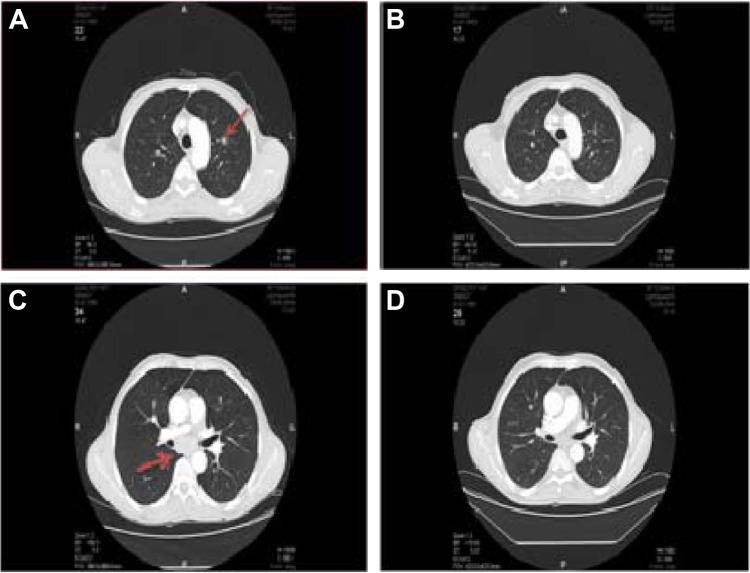

Figure 3.

Patient’s chest computed tomography (CT).

Notes: (A and C) Before treatment. (B and D) After treatment. The arrows represent the minimal enlargement of mediastinal lymph node.

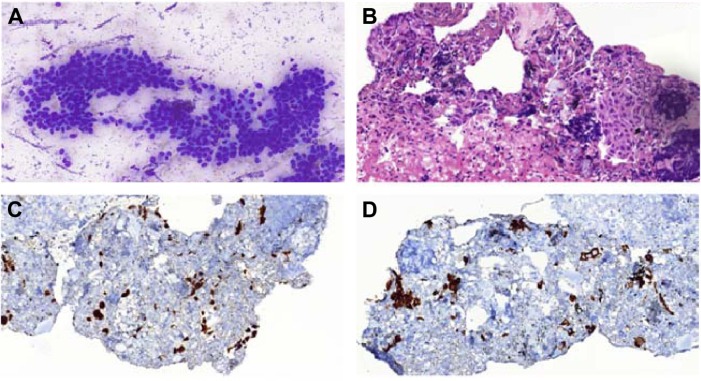

Figure 4.

Biopsy images.

Notes: (A) EBUS-FNA for mediastinal subcarinal lymph node: cytological appearance of nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. Sheets of atypical squamous cells with large hyperchromatic nucleus, dense squamoid cytoplasm, and moderate pleomorphism are observed (MGG stain, original magnification ×400). (B) A cell block section of tumor displaying few small atypical small squamous islands and scattered lymphocytes showing crushing artifact in a fibrinous background (H&E stain, original magnification ×400). Cell block immunohistochemistry of the tumor: tumor cells display strong nuclear p63 (C) and cytoplasmic cytokeratin 5/6 (D) positivities, which are characteristics for squamous cell carcinoma.

Abbreviations: EBUS-FNA, endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial fine-needle aspiration; MGG, May–Grünwald–Giemsa; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

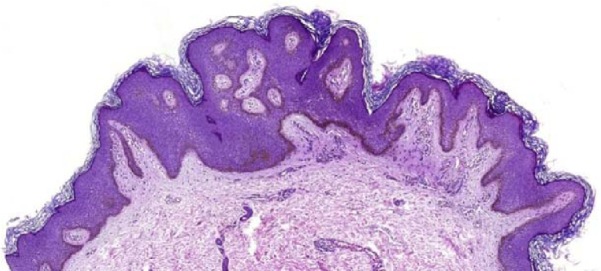

Figure 5.

The lesion manifests epidermal acanthosis and papillomatosis with increased deposition of melanin pigment along the epidermal basal layer (H&E stain, original magnification ×46).

Abbreviation: H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

With the diagnosis of squamous cell lung cancer, the patient was treated with six cycles of a combination chemotherapy regimen using docetaxel plus cisplatinum. After the six doses, we again performed a positron emission tomography scan and found out that there was no fludeoxyglucose involvement and left upper lobe lesion. The patient skin and oral mucosal lesion healed after the treatment (Figure 6). We then discussed the patient at our multidisciplinary oncological board. We decided to give radiotherapy to the primary region and then put the patient under observation. Ethical approval was obtained from the Hacettepe University ethics committee. A written informed consent form was obtained from the patient for the treatment and a verbal consent was obtained for the publication of this article as well as the use of all images.

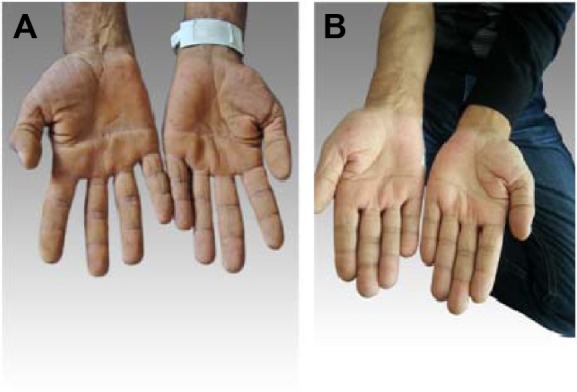

Figure 6.

The patient’s hands.

Notes: (A) Before treatment, tripe palms. (B) After treatment.

Discussion

Paraneoplastic syndromes occur in ~10% of patients with lung cancer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Paraneoplastic syndromes with lung cancer

| Paraneoplastic syndromes with lung cancer | Frequently caused by |

|---|---|

| Endocrine syndrome | |

| Hypercalcemia | Squamous cell (mostly), adenocarcinoma, SCLC |

| SIADH | SCLC |

| Cushing’s syndrome | SCLC (mostly), carcinoid tumor of lung |

| Neurologic syndrome | |

| Lambert–Eaton syndrome | SCLC |

| Limbic encephalopathy | SCLC |

| Cerebellar degeneration | SCLC |

| Autonomic neuropathy | SCLC |

| Skeletal manifestations | |

| Digital clubbing | NSCLC (mostly adenocarcinoma) |

| Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy | NSCLC (mostly adenocarcinoma) |

| Hematologic and vascular syndromes | |

| Anemia | NSCLC |

| Leukocytosis | NSCLC |

| Thrombocytosis | NSCLC |

| Hypercoagulable disorders | NSCLC (mostly adenocarcinoma) |

| Trousseau’s syndrome (migratory superficial thrombophlebitis) | |

| Deep venous thrombosis | |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy | |

| Cutaneous manifestations | |

| Polymyositis/Dermatomyositis | SCLC |

| AN | NSCLC (mostly adenocarcinoma) |

| Hyperkeratosis of palms and soles | NSCLC (mostly squamous cell) |

Abbreviations: SCLC, small cell lung cancer; SIADH, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; AN, acanthosis nigricans.

There are no pathognomonic dermatological signs of lung cancer, neither squamous, adeno, nor small cell. Various skin conditions are associated with some form of malignancy as paraneoplastic syndrome. Dermatomyositis, AN, erythema multiforme, urticaria, scleroderma, hyperpigmentation, and tripe palms are among the most common paraneoplastic skin lesions reported with various malignancies.12 AN is not a skin disease per se but a cutaneous sign of an underlying condition and disease (Table 2).

Table 2.

Etiology of AN

| Obesity | |

| Endocrine and metabolic disorders | Diabetes, polycystic ovarian syndrome |

| Genetic syndrome | Down syndrome, congenital lipodystrophy |

| Familial AN | |

| Drug interaction | Systemic glucocorticoids, injected insulin, oral contraceptives, niacin, nicotinic acid |

| Malignancy | Abdominal adenocarcinoma, particularly gastric adenocarcinoma |

Abbreviation: AN, acanthosis nigricans.

Obesity and diabetes mellitus are the most common medical disorders linked with AN. Although classically described as a sign of malignancy, AN is very rare. Benign types, sometimes described as “pseudoacanthosis nigricans”, are much more common.12 “Tripe palms” is merely the palmar manifestation of AN. An associated malignancy has been reported in >90% of patients with tripe palms.10 In one study, malignancy-associated tripe palms was detected in 79 patients who had a total of 86 cancers.10 Fifty-seven of these patients also had AN. Benign and malignant ANs are indistinguishable on histopathology. Involvement of mucous membrane is rare in the benign variety. AN with sudden onset, rapid progression, profound hyperkeratosis, and hyperpigmentation with coexisting pruritus and unexplained weight loss in older adults is usually associated with malignancy.13 In our case, a malignancy was suspected due to the rapid progression of skin lesion, involvement of oral mucosal membrane, and history of heavy smoking. Malignant AN has been mostly reported to be associated with tumors of gastrointestinal tract (90%), especially with carcinoma of stomach;5 liver, gall bladder, and bile duct cancers;14,15 and carcinoma of colon. Less frequently, it is associated with bronchogenic carcinoma7,16,17 and breast and ovarian cancer.18 In our case, we investigated gastrointestinal tract by endoscopy, colonoscopy, and CT scan of abdomen. There was no malignant lesion; only 2 cm of liver hemangioma was detected. If malignant AN is suspected in a patient without known cancer, it is extremely important to investigate for underlying malignancy and identify a hidden tumor. AN has no specific treatment and depends on the treatment of the underlying malignancy. If successfully treated, the skin lesion usually regresses. Corticosteroids and azathioprine have been tried in some patients with varying results. In our case, we treated the patient with chemotherapy, and after successful treatment, the oral mucosal ulcer and skin lesion resolved and the patient condition was nearly normal.

Conclusion

Rarely, AN occurs as a paraneoplastic disorder. Abdominal adenocarcinomas, particularly gastric adenocarcinomas, represent the majority of AN-associated tumors. In addition, AN was observed in squamous cell lung cancer in our study. Therefore, if a patient comes with a sudden onset of AN, we must carefully investigate the patient to determine any underlying malignancy. In our case, the patient was diagnosed at an advanced inoperable stage; however, with a low volume of disease and with effective treatment at that time, the patient became healthy and there was no evidence of disease documented.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Spiro SG, Gould MK, Colice GL, American College of Chest Physicians Initial evaluation of the patient with lung cancer: symptoms, signs, laboratory tests and paraneoplastic syndromes: ACCP evidenced-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition) Chest. 2007;132(3 Suppl):149S–160S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pelosof LC, Gerber DE. Paraneoplastic syndromes: an approach to diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(9):838–854. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McClelland MT. Paraneoplastic syndromes related to lung cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14(3):357–364. doi: 10.1188/10.CJON.357-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krawczyk M, Mykala-Ciesla J, Kolodziej-Jaskula A. Acanthosis nigricans as a paraneoplastic syndrome. Case reports and review of literature. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119(3):180–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeh JS, Munn SE, Plunkett TA, Harper PG, Hopster DJ, du Vivier AW. Coexistence of acanthosis nigricans and the sign of Leser-Trelat in a patient with gastric adenocarcinoma: a case report and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2 Pt 2):357–362. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(00)90112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukherjee S, Pandit S, Deb J, Dattachaudhuri A, Bhuniya S, Bhanja P. A case of squamous cell carcinoma of lung presenting with paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans. Lung India. 2011;28(1):62–64. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.76305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heaphy MR, Millnd JL, Schroeter AL. The sign of Leser-Trelat in a case of adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:386–390. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.104967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kannenberg SM, Koegelenberg CF, Jordaan HF, Bolliger CT. A patient with leonine facies and occult lung disease. Respiration. 2010;79(3):250–254. doi: 10.1159/000247186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pentenero M, Carrozzo M, Pagano M, Gandolfo S. Oral acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms and leser-trelat in a patient with gastric adenocarcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43(7):530–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen PR, Grossman ME, Silvers DN, Kurzrock R. Tripe palms and cancer. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11(1):165–173. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(93)90114-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruz PD, Hud JA. Excess insulin binding to insulin-like growth factor receptors: proposed mechanism for acanthosis nigricans. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;98(6 Suppl):82S–85S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12462293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisman K, Graham RM. Disorders of keratinisation. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffith C, editors. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 2004. pp. 34.1–34.11. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singhi MK, Jain V. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis with adenocarcinoma of stomach in a 35 years old man. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2005;71:55–56. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.16238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ravenborg L, Thomsen K. Acanthosis nigricans and bile duct malignancy. Acta Derm Venerol. 1993;73(5):378–379. doi: 10.2340/0001555573378379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scully C, Barett WA, Gilkes J, Rees M, Sarner M, Southcott RJ. Oral acanthosis nigricans, the sign of Leser-Treat and cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145(3):506–507. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bottoni U, Dianzani C, Pratenda G, et al. Florid cutaneous and mucosal papillomatosis with acanthosis revealing a primary lung cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2000;14(3):205–208. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lomholt H, Thestrup-Pedersen K. Paraneoplastic skin manifestation of lung cancer. Acts Derm Venerol. 2000;80(3):200–202. doi: 10.1080/000155500750042970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mekhail TM, Markman M. Acanthosis nigricans with endometrial carcinoma: case report and review of literature. Gynaecol Oncol. 2002;84(2):332–334. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]