SUMMARY

Vertigo and dizziness are common symptoms in the general population, with an estimated prevalence between 20% and 56%. The aim of our work was to assess the point prevalence of these symptoms in a population of 2672 subjects. Patients were asked to answer a questionnaire; in the first part they were asked about demographic data and previous vertigo and or dizziness. Mean age of the sample was 48.3 ± 15 years, and 46.7% were males. A total of 1077 (40.3%) subjects referred vertigo/dizziness during their lifetime, and the mean age of the first vertigo attack was 39.2 ± 15.4 years; in the second part they were asked about the characteristics of vertigo (age of first episode, rotational vertigo, relapsing episodes, positional exacerbation, presence of cochlear symptoms) and lifetime presence of moderate to severe headache and its clinical features (hemicranial, pulsatile, associated with phono and photophobia, worse on effort). An age and sex effect was demonstrated, with symptoms 4.4 times more elevated in females and 1.8 times in people over 50 years. In the total sample of 2672 responders, 13.7% referred a sensation of spinning, 26.3% relapsing episodes, 12.9% positional exacerbation and 4.8% cochlear symptoms; 34.8% referred headache during their lifetime. Subjects suffering from headache presented an increased rate of relapsing episodes, positional exacerbation, cochlear symptoms and a lower age of occurrence of the first vertigo/dizziness episode. In the discussion, our data are compared with those of previous studies, and we underline the relationship between vertigo/dizziness from one side and headache with migrainous features on the other.

KEY WORDS: Vertigo, Dizziness, Epidemiology, Migraine

RIASSUNTO

La vertigine e l'instabilità sono sintomi molto comuni nella popolazione la cui prevalenza è stimata tra il 20 e il 56%. L'obiettivo del nostro lavoro è stato quello di determinare la prevalenza di questi sintomi in una popolazione di 2672 soggetti. è stato somministrato loro loro un questionario; nella prima parte sono stati richiesti i dati demografici e se avessero mai sofferto di vertigine o instabilità nella loro vita. L'età media del campione è stata di 48,3 ± 15 anni, il 46,7% erano maschi. Sul totale della popolazione 1077 (40,3%) hanno riferito di aver sofferto di vertigine o instabilità nella loro vita, con un primo episodio occorso all'età di 39,2 ± 15,4 anni. Nella seconda parte del questionario sono state indagate le caratteristiche delle vertigini (età del primo episodio, il tipo di vertigine, presenza di più episodi, esacerbazione posizionale della vertigine, presenza di sintomi cocleari infine la presenza di cefalea da moderata o severa nel corso della vita e le sue caratteristiche cliniche (riferita a un emicrania, pulsante, associata a fono o fotofobia, peggiore con l'attività fisica). È stata osservata una correlazione della vertigine con l'età e con il sesso, essendo la prima 4,4 volte più frequente nelle donne e 1,8 volte nei soggetti con oltre 50 anni. Sul campione complessivo di 2672 soggetti, 13,7% hanno riferito vertigine rotatoria, 26,3% episodi recidivanti, 12,9% esacerbazione correlata alla posizione e il 4,8% presenza sintomi cocleari; il 34,8% ha lamentato cefalea nel corso della loro vita. I soggetti affetti da cefalea presentavano un'incidenza aumentata di vertigini recidivanti, di esacerbazione correlata alla posizione, di sintomi cocleari e un'età più giovane di comparsa del primo episodio di vertigine/instabilità. Nella discussione i nostri dati sono stati confrontati con quelli di precedenti studi. Gli autori sottolineano la correlazione tra vertigine/instabilità da un lato e cefalea con caratteristiche emicraniche dall'altro.

Introduction

Vertigo and dizziness are among the most common reasons for medical consultation 1 and they account for 2-3% of total consultations in emergency departments 2. It has been reported that nearly 26 million people needed a visit in an emergency department for dizziness/vertigo over a period of 10 years (1995-2004) in the US, with a median of 3.6 diagnostic tests per patient 3.

Previous studies focusing on epidemiology of vertigo and dizziness have reported a lifetime prevalence between 20% and 30% 4 5. In a recent questionnaire-based investigation, the authors calculated in a large cohort of 2987 French subjects that the 1-year prevalence for vertigo was 48.3%, for unsteadiness it was 39.1%, and for dizziness it was 35.6%. The three symptoms were correlated with each other and occurred mostly (69.4%) in various combinations rather than in isolation 6. In a meta-analysis, a lifetime prevalence of vertigo toward a vestibular disorder was seen in 3% to 10% of the total population 7. Moreover, dizziness, which is a more undefined condition, is frequently associated with other common diseases and conditions, such as migraine 8, motion sickness 9, orthostatic hypotension, sensation of fainting 10 and anxiety disorders 11.

A recent study confirmed previous findings on the marked female preponderance among individuals with vertigo (one-year male to female prevalence ratio of 1:2.7), and showed that vertigo is almost three times more frequent in the elderly compared to younger individuals 12.

Finally, vertigo and migraine are often comorbid conditions; with the exclusion of vestibular migraine, with prevalence of 0.98% 12, patients with Menière's disease present a higher rate of migraines (around 56%) than the total population 13, and migraineurs more often present benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) 14.

The main purpose of our work was to assess the prevalence of vertigo/dizziness in a Caucasian population and establish the relationship of these symptoms with headache and its migrainous features.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was an observational prospective study, based on a self administered questionnaire, carried on in 3 university centres in the period between January and April 2015; subjects were anonymously asked to participate, either connecting to a protected site or on a paper support randomly distributed among outpatients in the withdrawal centres. The first part included only demographic data (sex and age) and the question "Have you ever experienced vertigo and/or dizziness during your lifetime?". Patients were instructed to consider either the feeling that you are dizzily turning around or that your surroundings are dizzily turning about you. Only patients with a positive history for vertigo and/or dizziness were asked to complete the entire questionnaire. Questions to be answered are reported in Table I. Only subjects over 18 years old were included. To characterise the type of headache, four specific questions were included in the questionnaire regarding the feature of symptoms (hemicranial, pulsatile, associated with phono and photophobia and worse during physical efforts); a composite migraine risk score (MRS) was calculated for the patients suffering from headache, giving 2 points for every positive answer, so that MRS could range between 0 and 8.

Table I.

Questionnaire to be completed by subjects with a positive history for vertigo/dizziness.

| At which age did you experience your first episode of vertigo/dizziness? | |

| Do you experience the sensation that surrounding objects are moving or spinning? | |

| Do you have the sensation of a decrease of hearing level during vertigo? | |

| Did you experience a single episode or relapsing ones? | |

| Do you have an onset or increase of symptoms while lying down in bed? | |

| Have you suffered from moderate to severe headache during your lifetime? | A. Localised on one side? |

| If yes, did it present with any of the following features? | B. Pulsatile |

| C. Associated with phono- or photophobia | |

| D. Going worst during physical effort |

Population sample

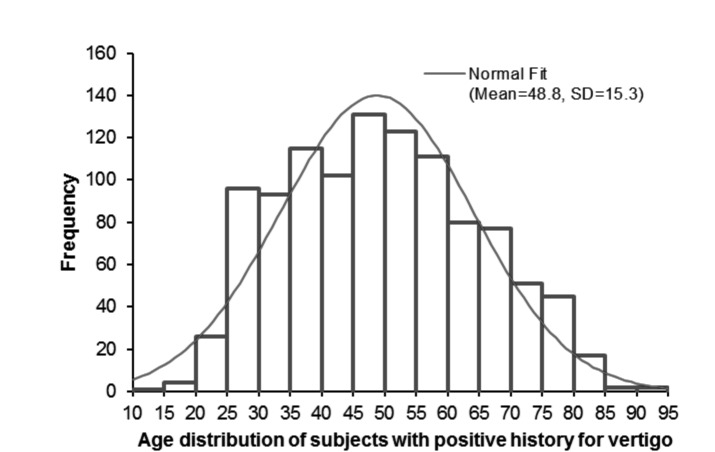

A total of 2672 subjects were included in the study; 1249 (46.7%) were males. Mean age was 48 ± 15.2 years (range 18 to 96). No difference was detected between the group of subjects with and without vertigo for the age at inclusion (48.8 ± 15.3 and 47.6 ± 15.1, respectively). In Table II sex and age distribution (over or below 50 years) are reported. Figure 1 shows the histogram of age distribution of subjects with a positive history for vertigo.

Table II.

Age and sex distribution of the sample.

| Sex | Age | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 50 years | > 50 years | ||

| Females | 820 | 603 | 1423 |

| Males | 716 | 533 | 1249 |

| Total | 1536 | 1136 | 2672 |

Fig. 1.

Age distribution of patients with a positive history for vertigo at inclusion.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables are reported as mean value ± standard deviation; differences were assessed by a two tailed t test. Categorical variables are reported as rates on total and a chi square test was performed to establish differences between groups. A linear regression model has been performed to quantify the vertigo risk in the 4 classes of subjects (males and females, below and over 50 years); data are reported as odds ratio (OR) (95% confidence interval [CI]). A linear regression test was also performed to correlate MRS with a clinical history of rotational, positional vertigo and with the age of the first vertigo episode. Analyses were carried out using STATA software v. 13 (Stata Corporation, College Station, 2013, Texas, USA).

Results

No difference were seen between the group of subjects with and without vertigo for age at inclusion (48.8 ± 15.3 and 47.6 ± 15.1, respectively). In Table II sex and age distribution (over or below 50 years) are reported. In Figure 1, the histogram of age distribution of subjects with a positive history for vertigo at inclusion is shown.

In the sample, 1077 of 2672 (40.3%) subjects reported at least one episode of vertigo/dizziness during their lifetime; 768 (71.3%) were females, while 309 (28.7%) were males. Independently from age, females presented a higher rate of vertigo than males (OR = 3.56, 95% CI 3.017225-4.199935; p ≤ 0.001). Independently of sex, vertigo was more represented in people over 50 years; 479 of 1077(44.5%) with a positive history of vertigo, while 367 of 1595 (23%) without vertigo were over 50 years (OR = 1.37, CI 1.171587- 1.60125; p ≤ 0.005). Considering 1 as the vertigo risk in the sample of males below 50 years, it was 1.8 times higher in males over 50 yo, 4.4 in females below 50 years and 5.2 times higher in females over 50 years (p ≤0.001). In our sample, lifetime risk of vertigo risk was estimated to increase by 1% every 10 years.

In the total sample, 367 of 2672 subjects (13.7%) referred a sensation of spinning or movement of surroundings, 702 relapsing episodes (26.3%), 130 (4.8%) the sensation of fluctuating hearing level during vertigo and 347 (12.9%) reported the onset or increase of vertigo while lying down. In the sample of 1077 dizzy subjects, 375 also reported headache episodes (34.8%), 254 with a MRS of at least 4 points, 110 with a score of 2 and only 11 with a score of 0. The prevalence of various features of vertiginous episodes was calculated in the total group and in the subgroup of subjects also referring headache:

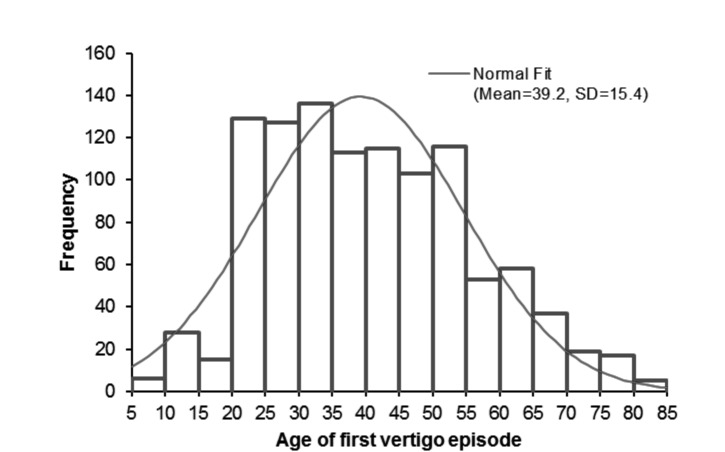

the age of the first vertigo (see Fig. 2) was 39.2 ±15.4 years, while in the subgroup of 375 subjects with headache it was 33.4±15.4 (p ≤ 0.001). Thirty-four subjects (1.2%) referred vertigo in a paediatric age, 33 reported headaches (all with a MRS of at least 4) and 25 were females. The MRS was 5 ± 2.2 in the sample of headache subjects, while it was 6.1 ±1.7 in the 34 subjects with paediatric vertigo (p ≤ 0.01);

a positional component was reported in 351 of 1079 subjects with vertigo (32.5%), in 146 of 375 (38.9%) subjects with headaches (p = 0.02) and 130 (51.2%) with a MRS of at least 4 (p ≤ 0.01);

a relapsing vertigo was reported in 702 of 1077 subjects (65%), in 280 of 375 (74.6%) headache sufferers (p ≤ 0.01) and in 242 of 254 (95%) subjects with a MRS of at least 4 (p ≤ 0.001);

a sensation of fluctuating hearing level was reported in 130 of 1077 (12%) dizzy subjects, in 63 of 375 (16.8%, p = 0.02) headache sufferers and in 52 (20.4%) subjects with at least 4 points on the MRS (p ≤ 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Age distribution for the first episode of vertigo/dizziness.

Finally, a linear regression test demonstrated an association between the MRS and a positional component of vertigo (p = 0.001), rotational vertigo (p ≤ 0.01), age of first vertigo attack (p ≤ 0.0001) and relapsing episodes of vertigo (p ≤0.0001).

Discussion

Our data are consistent with those published in previous reports. In our sample, the point prevalence for vertigo and or dizziness of any kind (i.e. without a definition of severity) was 40.3%. Previously published papers have reported different results, with a lifetime prevalence ranging between 23.2% and 59.2% 4 6, but when patients were asked if they experienced dizziness bad enough to interfere with daily activities, the positive responders decreased to 16.9-29.5% 4 12. It should be underlined that dizziness is a common and non-specific symptom and may be provoked by various disorders, including neurological, cardiovascular, vestibular and multisensory dysfunctions; moreover, a strict relationship has also been reported with anxiety and panic disorders 5 15. When asked about vertigo as a symptom (i.e. a sense of rotation or spinning), 13.7% of our sample referred to have experienced it; our data confirm those of previous papers reporting a rate in the range between 7.8% and 21% 4 12. Other studies, based on general practitioner records, estimated a 12 month incidence of vertigo between 1.78% and 3.4% 16 17. Commonly accepted clinical practice makes a distinction between vertigo and dizziness, with the first more often associated with a dysfunction of the vestibular system. Nonetheless, it has been underlined in epidemiologic studies that cultural and linguistic factors may play a role in the description of subjective symptoms 18 19.

In our sample, we found an increased prevalence of vertigo in females and in the elderly; in particular, females presented a 4.4-fold increased risk for vertigo, while the agerelated risk factor was estimated to be 1.8; these results are consistent with previously published reports 4 6 12 19-23.

More interesting data may be drawn about the correlation between vertigo from one side and headache and migraine to the other. Since not all patients referring moderate to severe headaches in our sample were migraineurs, we decided to assess the migraine probability with a score, the MRS, by evaluating 4 characteristics related to migraine (hemicranial, pulsatile, associated with phono and/or photophobia, worse with physical effort). Patients with higher MRS more frequently presented relapsing episodes of vertigo, referred a sensation of hearing level fluctuation during vertigo/dizziness and presented a lower age of occurrence of the first vertigo attack; moreover, all subjects referring vertigo in a paediatric age presented with a MRS greater than 4.

Far from being exhaustive, it should be noted that the relationship between vertigo and migraine is complex and it has been stated that it goes beyond the diagnostic concept of vestibular migraine 24 25, whose prevalence in total population has been estimated at 0.98% 26. For example, among patients diagnosed with Meniere's disease, 56% also presented migraine compared to 16% in the normal population 13; migraine has been found to be three times more common in patients with idiopathic BPPV 27 and two times more common in patients with idiopathic BPPV than in age and sex-matched controls 28. Vertigo may be a migraine precursor in a paediatric age 29, and motion sickness occurs more frequently in patients with migraine both in paediatric and adult ages, with a reported prevalence between 30% and 50% 30. Finally, an interrelation between migraine, anxiety and other psychiatric disorders and dizziness has been postulated and a clinical entity including the 3 disorders, the MARD, has been proposed 31. It should be underlined that vertigo/dizziness with a positional component may be related to BPPV, which is more represented among migraineurs, but it may also be one of the commonest findings in vestibular migraine 32. Moreover, our data underline that a sensation of decrease of hearing level during vertigo was reported in 12% of total dizzy patients, and above all in 20.4% of dizzy patients with a MRS of at least 4. This percentage includes patients with Meniere's disease, even if not confirmed; nonetheless, a recent paper reported that cochlear symptoms are far from being rare even in subjects with definite vestibular migraine, since 10.7% of patients referred a sensation of a hearing loss often during vertigo and 15.5% sometimes during vertigo 33 34.

As a final consideration, we want to underline the possible risks of bias in our work, above all linked to the representativeness of our sample; even if patients presenting for any ambulatory visit were excluded, and questionnaires were completed for a large part by subjects referring to hospital for a blood exam, it cannot be excluded that responders were above all subjects with previous episodes of vertigo. Nonetheless, our results are in the range of previously published data and confirm the high prevalence of vertigo/dizziness as a symptom in the general population.

Conclusions

Our data, in accordance with previously published reports, confirm the high prevalence of symptoms of vertigo/ dizziness in general population. Symptoms present a higher prevalence in females and in the elderly. Finally, an association with migraine was found.

References

- 1.Sloane PD. Dizziness in primary care. Results from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Fam Pract. 1989;29:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman-Toker DE, Hsieh YH, Camargo CA, Jr, et al. Spectrum of dizziness visits to US emergency departments: crosssectional analysis from a nationally representative sample . Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:765–775. doi: 10.4065/83.7.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerber KA, Meurer WJ, West BT, et al. Dizziness presentations in US emergency departments, 1995-2004 . Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:744–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kroenke K, Price RK. Symptoms in the community. Prevalence, classification, and psychiatric comorbidity . Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2474–2480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yardley L, Owen N, Nazareth I, et al. Prevalence and presentation of dizziness in a general practice community sample of working age people . Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48:1131–1135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bisdorff A, Bosser G, Gueguen R, et al. The epidemiology of vertigo, dizziness, and unsteadiness and its links to comorbidities . Front Neurol. 2013;22:e29–e29. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2013.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murdin L, Schilder AGM. Epidemiology of balance symptoms and disorders in the community: a systematic review . Otol Neurotol. 2014;36:387–392. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neuhauser H, Leopold M, Brevern M, et al. The interrelations of migraine, vertigo, and migrainous vertigo . Neurology. 2001;56:436–441. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.4.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dai M, Raphan T, Cohen B. Labyrinthine lesions and motion sickness susceptibility . Exp BrainRes. 2007;178:477–487. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0759-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newman-Toker DE, Dy FJ, Stanton VA, et al. How often is dizziness from primary cardiovascular disease true vertigo? A systematic review . J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:2087–2094. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0801-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruckenstein MJ, Staab JP. Chronic subjective dizziness. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2009;42:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neuhauser HK, Brevern M, Radtke A, et al. Epidemiology of vestibular vertigo: a neurotologic survey of the general population. Neurology. 2005;65:898–904. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000175987.59991.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radtke A, Lempert T, Gresty MA, et al. Migraine and Menière's disease: is there a link? . Neurology. 2002;59:1700–1704. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000036903.22461.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishiyama A, Jacobson KM, Baloh RW. Migraine and benign positional vertigo . Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:377–380. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacob RG, Furman JM, Durrant JD, et al. Panic, agoraphobia and vestibular dysfunction . Am J Psychiatr. 1996;153:503–512. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrigues HP, Andres C, Arbaizar A, et al. Epidemiological aspects of vertigo in the general population of the Autonomic Region of Valencia, Spain . Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:43–47. doi: 10.1080/00016480701387090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kruschinski C, Kersting M, Breull A, et al. Frequency of dizziness-related diagnoses and prescriptions in a general practice database . Zeit Evid Fort Qual Gesund. 102:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman Toker DE, Dy FJ, Stanton VA, et al. How often is dizziness from primary cardiovascular disease true vertigo? A systematic review . J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:2087–2087. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0801-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murdin L, Schilder GM. Epidemiology of balance symptoms and disorders in the community: a systematic review. Otol Neurotol. 2014;36:387–392. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakashima K, Yokoyama Y, Shimoyama R, et al. Prevalence of neurological disorders in a Japanese town. Neuroepidemiology. 1996;15:208–213. doi: 10.1159/000109909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nazareth I, Yardley L, Owen N, et al. Outcome of symptoms of dizziness in a general practice community sample. Fam Pract. 1999;16:616–618. doi: 10.1093/fampra/16.6.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai YT, Wang TC, Chuang LJ, et al. Epidemiology of vertigo: a National Survey. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:110–116. doi: 10.1177/0194599811400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gufoni M, Guidetti G, Nuti D, et al. The role of clinical history in the evaluation of balance and spatial orientation disorders in the elderly. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2005;25:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bisdorff A. Migraine and dizziness. Curr Opin Neurol. 2014;27:105–110. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farri A, Enrico A, Farri F. Headaches of otolaryngological interest: current status while awaiting revision of classification. Practical considerations and expectations. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2012;32:77–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lempert T, Neuhauser H. Epidemiology of vertigo, migraine and vestibular migraine. J Neurol. 2009;256:333–338. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishiyama A, Jacobson KM, Baloh RW. Migraine and benign positional vertigo. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;9:377–380. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lempert T, Leopold M, Brevern M, et al. Migraine and benign positional vertigo. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:1176–1176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niemensivu R, Kentala E, Wiener-Vacher S, et al. Evaluation of vertiginous children. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:1129–1135. doi: 10.1007/s00405-007-0329-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grunfeld E, Gresty MA. Relationship between motion sickness, migraine and menstruation in crew members of a 'round the world' yacht race. Brain Res Bull. 1998;47:433–436. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Furman JM, Balaban CD, Jacob RG, et al. Migraine-anxiety related dizziness (MARD): a new disorder? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.048926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polensek SH, Tusa RJ. Nystagmus during attacks of vestibular migraine: an aid in diagnosis. Audiol Neurootol. 2010;15:241–246. doi: 10.1159/000255440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez Escamez JA, Dlugaiczyk J, Jacobs J, et al. Accompanying symptoms overlap during attacks in Menière's disease and vestibular migraine. Front Neurol. 2014;5:e265–e265. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teggi R, Fabiano B, Recanati P, et al. Case reports on two patients with episodic vertigo, fluctuating hearing loss and migraine responding to prophylactic drugs for migraine. Menière's disease or migraine-associated vertigo? Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2010;30:217–217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]