Abstract

Background

Prepartying, or drinking before an event where more alcohol may or may not be consumed, has been positioned in the literature as a behavior engaged in by heavy drinkers. However, recent findings suggest that prepartying may confer distinct risks, potentially causing students to become heavier drinkers over time.

Objectives

The goals of this study were to disentangle the longitudinal relationships between prepartying, general and episodic alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related consequences by investigating 1) whether prepartying is associated with future consequences above and beyond current alcohol consumption habits and 2) whether augmentations in approval for alcohol and related increases in drinking mediate this relationship.

Methods

One-hundred and ninety-five undergraduates completed online questionnaires at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months later.

Results

Prepartying frequency was more strongly related to alcohol-related consequences one year later than was overall or episodic drinking. Additionally, a path mediation model confirmed our hypothesis that this relationship is due to gradual increases in drinking which occur as a result of more approving attitudes toward alcohol brought on by exposure to prepartying.

Conclusion/Importance

Findings suggest a new model for conceptualizing the relationship between prepartying, drinking, and consequences whereby students who get involved in prepartying may witness slow increases in their approval for alcohol use and, as a result, consumption. Importantly, results suggest that the increases in drinking displayed by prepartiers over the course of a year may account for the strong relationship between prepartying and later consequences. Prevention and intervention initiatives may benefit from directly targeting prepartying as a means of tempering risky alcohol use trajectories during one’s college tenure.

Keywords: prepartying, pregaming, alcohol, alcohol-related attitudes, alcohol-related consequences

Prepartying, or consuming alcohol prior to attending a party or event at which more alcohol may or may not be consumed (Pedersen & LaBrie, 2007), is considered to be a high-risk drinking behavior that is especially prevalent among heavier college student drinkers. For instance, students who begin prepartying during their first semester of college are more likely to have been heavier drinkers in high school compared to those who do not initiate prepartying during the same period (Haas, Smith, & Kagan 2013). Similarly, college students who engage in heavy episodic drinking (HED; 5 drinks in a row for males, 4 drinks for females; Wechsler, Dowdall, Davenport, & Rimm, 1995) preparty more often than those who do not engage in HED (Haas, Smith, Kagan, & Jacob, 2012). Research has also demonstrated that people who exhibit signs of an alcohol use disorder are more likely to preparty than those who do not display these symptoms (Barry, Stellefson, Piazza-Gardner, Chaney, & Dodd, 2013). With respect to overall drinking patterns, individuals who preparty consume more alcohol than non-prepartiers even on the days when they do not preparty (Read, Merrill, & Bytschkow, 2010). The relationship between prepartying and risky drinking indicators is clearly strong.

Prepartying is part of a constellation of risky drinking behaviors which have been linked with certain predilections toward a variety of alcohol-related behaviors and attitudes. For example, those who have high positive expectancies with regard to alcohol consumption (e.g., it would make it easier to talk with people) are more likely to preparty and play drinking games than those with lower expectancies (Zamboanga, Schwartz, Ham, Borsari, & Van Tyne, 2010). Also, students who preparty are more likely to report that the reason they drink is to get intoxicated (Reed et al., 2011; Wahl, Sonntag, Roehrig, Kriston, & Berner, 2013) and that they agree with statements reflecting the stereotypical college drinking culture, like “college is a time for experimentation with alcohol” (Moser, Pearson, Hustad, & Borsari, 2014). Regarding personality traits, those who preparty tend to display a greater propensity to seek out immediate reward and positive feelings (Haas et al., 2013). In sum, these findings demonstrate that prepartying has been positioned in the literature as a behavior engaged in by heavy drinkers, who already display positive attitudes toward alcohol use.

Consequences Associated with Prepartying

One of the main reasons prepartying and related behaviors like drinking games have received so much empirical attention in recent years is that they have consistently been linked to negative alcohol-related consequences at the event level (see, for example, Hummer, Napper, Ehret, & LaBrie, 2013; Labhart, Graham, Wells, & Kuntsche, 2013). On nights that involve prepartying, students are almost three times more likely to experience a blackout (Hummer et al., 2013; LaBrie, Hummer, Kenney, Lac, & Pedersen, 2011) and 2.5 times more likely to get into a fight (Hughes, Anderson, Morleo, & Bellis, 2008; Wahl et al., 2013). Overall, on days when drinkers preparty they experience twice as many negative alcohol-related consequences, like missing work/classes or having problems with a loved one because of drinking, compared to occasions when they do not preparty (Merrill, Vermont, Bachrach, & Read, 2013).

The reason people experience such high levels of consequences on nights when they preparty might appear obvious: because they consume significantly more alcohol on nights when they preparty than on nights when they do not. Indeed, prepartying has been identified as one of the strongest predictors of daily drinking levels among college students, with participants consuming 46% more drinks on evenings when it occurs (Barnett, Orchowski, Read, & Kahler, 2013). This high amount of consumption means it is much more likely that drinkers are engaging in HED on evenings when they preparty. The proportion of evenings on which people’s consumption can be classified as HED is 21%–34% higher when prepartying occurs than when it does not (Labhart et al., 2013; Pedersen & LaBrie, 2007). Students are also significantly more likely to exhibit “extreme drinking”, or consuming 8+/10+ drinks, on nights when they preparty (Fairlie, Maggs, & Lanza, 2014). Thus, it may seem to come as no surprise that higher amounts of drinking throughout an evening as the result of prepartying subsequently leads to higher blood alcohol concentrations (BACs; Barry et al., 2013; Clapp et al., 2009; Hummer et al., 2013) and a greater number of alcohol-related consequences (Foster & Ferguson, 2013; Merrill et al., 2013).

Limitations within the Current Perspective

The findings reviewed paint a compelling picture; prepartying leads to a greater likelihood for adverse consequences because drinkers consume more alcohol on evenings when they preparty than on evenings when they do not. In support of this conceptual model, a recent study by Labhart and colleagues (2013) found prepartying to be linked to adverse risky outcomes only indirectly; the relationship was fully mediated by greater drinking on evenings that included prepartying. Similarly, Read et al. (2010) reported that when controlling for drinks consumed per day, the association between prepartying and consequences became nonsignificant, suggesting that prepartying does not present additional risk above and beyond general alcohol consumption.

However, the findings of other recent studies suggest an alternative conceptual model in which prepartying does in fact confer distinct risks. In contrast with Read et al. (2010), Merrill et al. (2013) and Haas et al. (2012) both demonstrated that prepartying predicts additional variance in alcohol-related consequences above and beyond general consumption. Additionally, Kenney, Hummer, and LaBrie (2010) showed that prepartying predicted alcohol consequences across the transition from high school to college; when controlling for weekly high school drinking, participants who reported prepartying in high school experienced a disproportionately greater amount of consequences in college than those who had not prepartied. Similarly, Haas et al. (2013) found that students who prepartied in the months prior to college matriculation and continued to do so after arriving on campus increased their overall drinking significantly during the first months of college compared with students who did not preparty. Taken together these findings suggest that, while there is conflicting evidence as to whether prepartying predicts event-level consequences above and beyond alcohol consumption, there is preliminary evidence that prepartying does predict additional variance in consequences and consumption when these outcomes are assessed longitudinally. Unfortunately, the findings by Kenney et al. (2010) are cross-sectional and high school drinking and prepartying were assessed retrospectively; thus causality could not be established. The data presented by Haas et al. (2013) are longitudinal, but the authors did not assess the effect of baseline prepartying on later consequences over and above baseline or later alcohol consumption. Similarly, in both of these examples the participants matriculated to college during the course of the study, a major life change, and thus the findings may not be generalizable to individuals living under more stable circumstances. Further exploring these relationships while addressing the limitations in study design can potentially strengthen our understanding of the mechanisms by which prepartying can increase risk for the individual.

A New Theoretical Model

The current research seeks to provide evidence for a new theoretical model to explain the relationships between prepartying, general alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related consequences. We propose that engaging in frequent prepartying leads to gradual overall increases in an individual’s drinking rather than just facilitating higher consumption on evenings when it occurs. There are a number of different reasons for which students begin prepartying (e.g., to conform to peer pressure) even if they are not already heavy drinkers (for a review of prepartying motives, see LaBrie, Hummer, Pedersen, Lac, & Chithambo, 2012). Whatever the reason, simply prepartying more frequently may result in a greater degree of approval for other heavy-drinking behaviors, which in turn may translate to increases in one’s overall alcohol use and a greater likelihood of experiencing alcohol-related problems. We aim to test this hypothesis by shifting the focus away from prepartying being merely a correlate of heavy drinking to being a potentially important determinant of future heavy drinking and associated risk.

The tenets of Self-Perception Theory (Bem, 1972) provide a theoretical lens with which to view the proposition that prepartying predicts future alcohol risk. Self-perception theory asserts that attitudes and behavior are bidirectional in nature—ones’ attitudes influence one’s behavior while one’s actions also have the ability to influence one’s attitudes (Bem, 1967). The theory is closely related to Cognitive Dissonance Theory (Festinger, 1962) except that Self-Perception Theory does not necessitate feelings of dissonance in order to result in attitudinal change (Fazio, Zanna, & Cooper, 1977). Thus, increases in one’s drinking behavior as a function of more frequent prepartying may or may not be salient enough to cause cognitive dissonance. However, regardless of whether or not dissonance is produced, such an increase may spur the development of more approving attitudes toward drinking, which in turn may mediate the relationship between prepartying and future drinking behavior.

The Present Study

Building on findings by Kenny et al. (2010) and Haas et al. (2013) our initial goal was to improve understanding of the longitudinal relationships between prepartying, typical drinking patterns, and alcohol-related consequences. To accomplish this aim, we examined data on drinking attitudes and behaviors among college students across a one-year period. We hypothesized that prepartying at baseline would be positively associated with alcohol-related consequences one year later, above and beyond baseline drinking. Further, and consistent with Self-Perception Theory, we tested personal approval toward heavy drinking as a mediating mechanism through which prepartying influences later alcohol consumption. Our hypothesis was that this increase in drinking as a result of positive augmentations in approval would explain the link between prepartying and future consequences. In other words, our final prediction anticipated that approving attitudes towards drinking and the resulting increase in alcohol consumption would mediate the relationship between prepartying and later consequences.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Participants were students assigned to the control condition of a larger intervention study conducted at two west coast universities. One site is a large public university with an undergraduate student body of approximately 30,000 while the other is a mid-sized private university with an enrollment of approximately 5,600 undergraduate students. A random sample of 6,000 students, stratified across class year and equally portioned from both universities, was recruited via mail and email during September and October of 2010 to take part in a study on college student alcohol use. Of the 6,000 students invited, 2,689 (44.8%) completed an initial online screening survey and those who met the inclusion criterion by reporting at least one instance of HED in the past 30 days (n = 1,493; 55%) were invited to participate in the year-long study. Of the students who were invited, 1,367 (91.6%) completed an online questionnaire that served as the baseline for the study. Recruitment rates were comparable to other large-scale studies among this population (e.g., Marlatt et al., 1998; McCabe, Boyd, Couper, Crawford, & d’Arcy, 2002; Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Larimer, 2007).

In total, participants spent approximately one hour completing the screening and baseline surveys, for which they were paid $30. After completing baseline students were randomly assigned to one of five experimental conditions. Four of the five groups received various interventions and are not included in the current study. Those who were assigned to the assessment only control condition, 236 students, were emailed links to 25-minute follow-up surveys in March/April and again in the following September/October and were paid $20 for completing each of them. The final sample for the current study consisted of 195 students (121 female and 74 male) who completed the baseline and both follow-up surveys (82.6% retention rate). There were no significant differences on any study or demographic variables between the 41 participants lost to attrition and the 195 participants who completed all three assessments and are included in analyses. Participants were 70.2% White/Caucasian, 11.0% Asian, 9.9% Multiracial, 2.1% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 3.7% Black or African American, .5% American Indian, and 2.6% “Other”. The mean age of participants in the final sample at the start of the study was 20.15 (SD = 1.35) years.

Measures

Descriptive information about participants’ age, residence type (e.g., on campus, in a fraternity house, etc.), and whether or not they were involved with Greek life was assessed during both the initial and final surveys. Based on this information dichotomous variables were computed denoting whether a given participant turned 21, left or joined a fraternity or sorority, or changed their residence type (i.e. moved off campus) during the study period.

Weekly drinking was measured at screening and during both of the follow-ups using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985; Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1999), which asks participants to think of a typical week during the past 30 days and to estimate the number of drinks they consumed on each day of the week. One drink was defined for participants as 4–5 oz. of wine, a 10-oz. wine cooler, 12 oz. of beer (8 oz. of Canadian, malt liquor, or “ice” beers, or 10 oz. of a microbrew), or 1 cocktail with 1 oz. of 100-proof liquor or 1.25 oz. of 80-proof liquor. The number of drinks reportedly consumed on each day was summed to create a total weekly drinks score. The DDQ has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of college student drinking (e.g., Larimer et al., 2001; Marlatt et al., 1998). It has demonstrated good convergent validity (e.g., r = .50; Collins et al., 1985) and test-retest reliability (e.g., r = .87; Neighbors, Dillard, Lewis, Bergstrom, & Neil, 2006).

Maximum eBAC was calculated at both the initial and final survey. Participants were asked to think back to the occasion on which they drank the most in the last month (30 days) and to answer how many drinks they consumed and over the course of how many hours they were drinking. This information along with their height and weight was used to calculate their estimated maximum BAC.

Prepartying-related variables were only assessed during the baseline questionnaire. Consistent with past literature, prepartying was defined for participants as “…the consumption of alcohol prior to attending an event or activity (e.g., party, bar, concert) at which more alcohol may or may not be consumed.” Students indicated their frequency of prepartying with the following item: “In the last 30 days, how many days did you engage in prepartying?” Prepartying alcohol consumption was assessed using the following item: “During the last time that you prepartied, how many drinks did you consume while prepartying (before going out)?”

Alcohol-related consequences were measured during screening and again at the 12-month follow-up using the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989), a 23-item questionnaire which assessed problems encountered during the past three months either during or as a result of consuming alcohol. Items included “Went to school or work high or drunk”, “Felt that you had a problem with alcohol”, and “Had a fight, argument, or bad feelings with a friend” and participants were asked whether or not they had experienced each consequence during the past three months. Responses to all 23 items were summed to create a total consequences score (α = .93 in the current sample).

Approval of alcohol use was assessed at all three time points using four items designed to capture students’ approval of social and heavy drinking behaviors (Baer, 1994). Participants were asked to report the extent to which they approved or disapproved of “drinking alcohol every weekend”, “drinking alcohol daily”, “driving a car after drinking”, and “drinking enough to pass out”. Answers were entered on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disapprove) to 7 (strongly approve). Responses for all four items were averaged to create a composite alcohol approval score for each participant.

Analytic Plan

After first assessing correlations and general descriptive statistics, independent t-tests were conducted to document the presence of any notable gender differences in key study variables. Next, the longitudinal relationship between prepartying at time 1 (T1) and negative consequences experienced a year later (T3) was examined. Specifically, we were interested in whether the frequency with which participants prepartied and/or the amount of alcohol consumed while prepartying at T1 would be positively associated with consequences at T3 over and above overall drinking and maximum eBAC at T1. Because bivariate correlations and means for several study variables differed by gender, sex was included as a covariate. Additionally, during the 12-month study fifty-five participants turned 21, eighteen participants either joined or left a fraternity or sorority, and sixty-seven participants changed their residency type (e.g. moved off campus). These life changes are all likely to impact alcohol consumption and were thus controlled for in our models as well. Attempts to winsorize the alcohol-related consequences outcome did not result in a linear distribution as the SD remained significantly higher than the mean. Thus, the use of a Poisson model was indicated, in which we tested the effects of T1 prepartying on T3 consequences while controlling for T1 drinking and demographic changes. However, the resulting chi-square/df value was 4.15, suggesting the data was overdispersed and a poor fit for Poisson regression. Next, we attempted a negative binomial model using the same variables and the chi-square/df value in this case was .93, suggesting a strong fit (1.00 is ideal; Hilbe, 2014).

Next, in the presence of a significant effect of either prepartying frequency or consumption on future consequences, we evaluated whether this relationship might be meditated by changes in drinking over time brought on by positive augmentations in participants’ approval of alcohol use. Consistent with Self-Perception Theory, we expected alcohol approval and alcohol consumption assessed at 6 months (T2) to explain a substantial portion of the relationship between prepartying at T1 and consequences at T3. To evaluate this hypothesis, a negative binomial two-step two mediator structural equation model was constructed using Mplus (Hayes, 2009; Muthén & Muthén, 2001) in which T3 consequences was regressed on T2 weekly consumption, T2 alcohol approval, T1 prepartying frequency or consumption (depending on the results of the first regression), as well as the same control variables used previously and T1 consequences. Next, T2 weekly consumption was regressed on T2 approval and T1 prepartying, also controlling for T1 weekly drinking and the same covariates. Finally, T2 alcohol approval was regressed on T1 prepartying, controlling for T1 approval as well as sex, changes in residency or Greek status, and whether participants turned 21 during the study. Indirect paths within the model were also assessed for statistical significance.

Results

Descriptives, Correlations, and Gender Differences

Descriptive statistics for all variables are provided in Table 1 and are accompanied by bivariate associations in Table 2. Of note, T1 prepartying frequency was positively and significantly related to all study variables, including T3 drinking and consequences. Additionally, males drank significantly more and were more approving of alcohol use than females at all timepoints assessed. Also, males reported experiencing slightly more alcohol consequences during the T1 assessment but by T3 this difference was no longer significant.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for all study variables assessed at baseline (T1), 6 months (T2), and 12 months (T3)

| Males (N=74) | Females (N=121) | Overall (N=195) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| % (N) | M (SD) | % N | M (SD) | % (N) | M (SD) | ||

| T1 | Age | 20.45 (1.33) | 19.95 (1.32) | 20.14 (1.34)** | |||

| Greek involved | 35.1 (26) | 26.7 (32) | 29.9 (58) | ||||

| Live in frat/sorority | 14.9 (11) | 9.1 (11) | 11.3 (22) | ||||

| Live off campus | 51.4 (38) | 38.8 (47) | 43.4 (85) | ||||

| Live on campus | 23.0 (17) | 43.0 (52) | 35.4 (69)** | ||||

| Live with parents | 10.8 (8) | 9.1 (11) | 9.7 (19) | ||||

| Prepartying frequency | 5.34 (4.18) | 4.86(4.18) | 5.03 (4.18) | ||||

| Drinks at last preparty | 5.05 (3.45) | 3.85 (2.02) | 4.30 (2.70)** | ||||

| Max eBAC | .17 (.10) | .17 (.10) | .17 (.10) | ||||

| Weekly drinking | 16.00 (11.92) | 8.73 (7.28) | 11.42 (9.89)*** | ||||

| Alcohol approval | 2.88 (.97) | 2.39 (.72) | 2.58 (.85)*** | ||||

| Alcohol consequences | 5.75 (5.71) | 4.39 (3.72) | 4.91 (4.62)* | ||||

|

| |||||||

| T2 | Alcohol approval | 2.94 (.97) | 2.36 (.83) | 2.58 (.93)*** | |||

| Weekly drinking | 15.06(12.44) | 9.19(8.61) | 11.44(10.56)*** | ||||

|

| |||||||

| T3 | Age | 21.47 (1.32) | 20.94 (1.31) | 21.14 (1.33)** | |||

| Greek involved | 34.2 (25) | 33.9 (41) | 34.0 (66) | ||||

| Live in frat/sorority | 9.6 (7) | 5.0 (6) | 6.7 (13) | ||||

| Live off campus | 68.5 (50) | 69.2 (83) | 68.9 (133) | ||||

| Live on campus | 9.6 (7) | 19.2 (23) | 15.5 (30) | ||||

| Live with parents | 12.3 (9) | 6.7 (8) | 8.8 (17) | ||||

| Alcohol consequences | 4.84 (5.94) | 4.09 (4.78) | 4.37 (5.25) | ||||

Note. Gender differences among study variables were identified by Student’s t-tests; significant gender differences are flagged in the overall column.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 2.

Correlations between study variables with females (N = 121) above the diagonal and males (N = 74) below.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Prepartying frequency (T1) | -- | .38*** | .50*** | .56*** | .40*** | .32*** | .41*** | .34*** | .30*** |

| 2 Drinks at last preparty (T1) | .319** | -- | .48*** | .45*** | .127 | .25** | .16 | .27** | .20* |

| 3 Max eBAC (T1) | .47*** | .26* | -- | .65*** | .34*** | .31*** | .26** | .34*** | .19* |

| 4 Weekly drinking (T1) | .71*** | .47*** | .59*** | -- | .42*** | .29** | .36*** | .29*** | .26** |

| 5 Alcohol approval (T1) | .55*** | .21 | .29** | .52*** | -- | .13 | .60*** | .18* | .11 |

| 6 Alcohol consequences (T1) | .40*** | .17 | .36*** | .47*** | .26* | -- | .18* | .42*** | .57*** |

| 7 Alcohol approval (T2) | .52*** | .04 | .23 | .19 | .62*** | .14 | -- | .39*** | .31*** |

| 8 Weekly drinking (T2) | .71*** | .21 | .55*** | .68*** | .40*** | .30* | .34** | -- | .64*** |

| 9 Alcohol consequences (T3) | .39*** | .06 | .32** | .28* | .14 | .63*** | .23 | .46*** | -- |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Prepartying and Alcohol-Related Consequences

Raw and exponentiated parameter estimates from the initial negative binomial regression predicting consequences at T3 are presented in Table 2. To facilitate the comparison of effect sizes across variables, all regression weights and parameter estimates are standardized (e.g., a 1 unit increase in BAC does not make sense and is impossible to compare with a 1 unit increase in prepartying). The exponentiated parameter estimates are interpreted in the same manner as rate ratios. For instance, the estimate for prepartying frequency is 1.457, indicating that each increase of one standard deviation in prepartying frequency at T1 was associated with experiencing an average of 45.7% more consequences at T3, even after controlling for the effect of sex, T1 general and episodic drinking behavior, and whether participants turned 21, joined or left Greek life, or changed residence type during the study. Taking into account the size of the standard deviation for prepartying frequency (4.18) this translates to an increase of around one instance of prepartying per week. In addition, the Wald chi-square statistic (T) indicates the strength of the evidence of a non-zero correlation. Thus, prepartying frequency at T1 can be seen to have a stronger relationship with consequences at T3 than does general alcohol consumption, the number of drinks consumed while prepartying, or maximum eBAC, none of which reached statistical significance.

Mediation Model

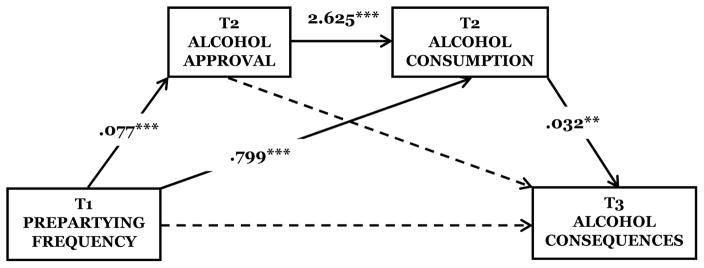

Next, because T1 prepartying frequency was found to be associated with T3 alcohol-related consequences in the regression model, a mediation model was constructed per our analytic plan which revealed that this relationship was fully mediated by T2 alcohol approval and alcohol consumption (see Figure 1 for a depiction). Specifically, prepartying was associated with the development of more approving attitudes toward alcohol and greater overall consumption six months later which, in turn, was associated with experiencing a greater number of alcohol-related consequences six more months hence (see Table 4 for full results of the path analysis). Further, significant indirect effects emerged from T1 prepartying frequency to T3 consequences through both T2 alcohol approval and T2 alcohol consumption (p = .034) as well as from prepartying frequency to consequences through alcohol consumption alone (p = .010). Additionally, the direct effect of prepartying frequency on consequences was nonsignificant, suggesting that the relationship was fully explained by the two indirect paths.

Figure.

The supported mediation model. Unstandardized coefficients are displayed for all model paths.

Table 4.

Full results of the negative binomial mediation model. All coefficients are unstandardized.

| Outcomes

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2 Alcohol Approval

|

T2 Alcohol Consumption

|

T3 Consequences

|

|||||||

| Predictors | b | SE | p | b | SE | p | b | SE | p |

| Intercept | 1.91 | 0.18 | .000 | −2.28 | 2.11 | .282 | −0.21 | 0.35 | .554 |

| T1 Alcohol Approval | 0.14 | 0.03 | .000 | ||||||

| T1 Alcohol Consumption | 0.36 | 0.08 | .000 | ||||||

| T1 Consequences | 0.10 | 0.02 | .000 | ||||||

| T2 Alcohol Consumption | 0.03 | 0.01 | .004 | ||||||

| T2 Alcohol Approval | 2.63 | 0.67 | .000 | 0.15 | 0.11 | .180 | |||

| T1 Prepartying Frequency | 0.08 | 0.02 | .000 | 0.80 | 0.18 | .000 | −0.02 | 0.03 | .546 |

| Maximum eBAC | 0.01 | 0.02 | .623 | −0.02 | 0.17 | .899 | 0.01 | 0.02 | .695 |

| Sex | −0.31 | 0.13 | .018 | −2.47 | 1.18 | .036 | 0.26 | 0.19 | .183 |

| Turned 21 During Study | −0.06 | 0.13 | .613 | 0.87 | 1.15 | .446 | 0.09 | 0.18 | .606 |

| Changed Greek Status | −0.15 | 0.09 | .104 | 0.44 | 0.82 | .588 | 0.12 | 0.13 | .335 |

| Changed Residence Type | 0.01 | 0.03 | .748 | 0.08 | 0.24 | .750 | 0.03 | 0.04 | .519 |

Discussion

This study provides preliminary evidence that prepartying may be better conceived as not merely a correlate, but also as a potentially important determinant of future heavy drinking and associated alcohol risk. The results of the current investigation, drawn from a year-long longitudinal dataset, suggest that an increase in prepartying of just once per week confers distinct risk above and beyond the increase in concomitant alcohol consumption—it leads, on average, to the experience of 45.7% more alcohol-related consequences a year later even when current consumption is controlled for. Additionally, we found that these consequences appear to be a direct result of increases in alcohol consumption over the course of the year as prepartiers gradually develop more approving attitudes toward risky drinking and thus increase their consumption. These findings are consistent with the proposed theoretical model involving Self-Perception Theory (Bem, 1972); as students begin prepartying more frequently, spending more time with other heavy-drinkers, they come to see risky drinking as a more common and acceptable behavior and thus become more likely to do so in the future.

The present research extends the work of Kenney, Hummer, and LaBrie (2010), which showed that when controlling for weekly high school drinking, prepartying in high school led to a greater amount of consequences in college. It also supports and extends the findings of Haas et al. (2013), who showed that students who prepartied in the months prior to college matriculation and continued to do so after arriving on campus increased their overall drinking significantly during the first months of college compared with students who did not preparty. The mediation model presented here fills a gap in the literature by explaining why the link between prepartying and future alcohol consumption and consequences exists, providing a new theoretical framework through which to think about the relationships between these variables. Unlike the data presented by Kenney et al., which were cross-sectional, the data utilized in the current study were longitudinal, following the same cohort of students over the course of a year. This allows for conclusions regarding the temporal nature of these constructs. If it were only true that increases in drinking and in approval of drinking caused increases in prepartying then we would not expect baseline prepartying to be associated with later drinking and approval over and above total baseline drinking and approval. However, we did find a significant positive relationship between baseline prepartying and alcohol consumption and approval 6 months later even when baseline drinking and approval were controlled for. This is indicative of a causal relationship, extending the work of Haas et al. (2013), who presented longitudinal data but did not assess the effect of prepartying on later outcomes over and above alcohol consumption.

Implications

On the whole, empirical evidence has supported a view that prepartying is particularly common among heavier drinkers and those who hold permissive attitudes about alcohol use more generally. While this may be true, it represents an incomplete picture. We have shown that prepartying also leads to the development of more approving attitudes. Given this finding it can be inferred that not all prepartiers have highly approving attitudes before they begin prepartying; otherwise prepartying would not necessarily be a significant predictor of individuals’ approval of heavy drinking over time. Thus, the people most susceptible to the pernicious effects of prepartying may be those who have the least approving attitudes toward drinking when they begin to incorporate prepartying into their alcohol use repertoire.

College alcohol interventions have often targeted reductions in drinks per week as a main outcome of interest (e.g., Baer, Kivlahan, Blume, McKnight, & Marlatt, 2001; Borsari & Carey, 2005). However, the results of the present study suggest that researchers and college student personnel should pay greater attention not just to the number of drinks students consume but also the context or manner in which the drinking occurs. Frequent engagement in prepartying confers unique risk compared to typical consumption patterns. Specifically, we found that the number of times students preparty bestows distinctive risk above and beyond general consumption but the number of drinks consumed while prepartying does not. Given the vital role that prepartying plays, both in terms of its direct and indirect effects on future drinking and risk, it behooves those who are interested in mitigating alcohol-related problems among college students to focus prevention and intervention efforts on reducing incidence of prepartying rather than simply targeting reduced overall consumption. Preventing initiation into prepartying, or at least educating students on the many risks associated with prepartying, may prevent the outgrowth of more permissive attitudes, thereby minimizing trajectories to future heavy drinking.

Directions for Future Research

Prepartying frequency was only assessed during baseline in the current study and thus some questions about the longitudinal nature of the construct remain unanswered. For instance, the theoretical paradigm presented here, based on Self-Perception Theory, suggests a bi-directional relationship between prepartying frequency and other alcohol use variables. However, because prepartying was not assessed at T2 and T3 in the current study we were unable to fully explore this possibility (e.g., a cross-lagged model). Future researchers should extend the results presented in the present paper by controlling for changes in prepartying during the study period. Additionally, while the relationship between prepartying and consequences was fully mediated in our model, the direct path from prepartying to later drinking remained significant, suggesting that alcohol approval only partially mediates the relationship. This suggests there may be additional variables that also help to explain how prepartying leads to increases in consumption, which future researchers may wish to explore. One possibility, based on Social Norms Theory (Berkowitz, 2004; Perkins, 2002) is that prepartying leads to the development of inflated perceptions of how much others drink which causes prepartiers to feel pressure to increase their own drinking. Future research will want to look more deeply at how prepartying increases risk, including the risk associated with increases in approving attitudes toward drinking as well as that associated with changes in normative beliefs or other related constructs. It will also be important to determine what specific elements of prepartying confer the most risk (e.g., frequency, time spent prepartying, persons present, etc.). The current study examined just two prepartying-related variables.

Conclusion

Results of the present investigation suggest that prepartying may be an even better indicator of future alcohol-related risk than current consumption levels; an increase in prepartying frequency by just one instance per week led to a 45.7% increase in alcohol-related consequences a year later. Prepartying was found to lead to increases in permissive attitudes toward heavy drinking behaviors which, in turn, was related to increased drinking and ultimately to a greater number of consequences. Thus, prevention and intervention initiatives may benefit from directly targeting prepartying as a means of tempering risky alcohol use trajectories during one’s college tenure.

Table 3.

Negative binomial regression predicting consequences at T3 (12 months).

| Variables | β | SE B | T | e ^ B | Low 95% | High 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | −.040 | .104 | .145 | .961 | .783 | 1.179 |

| Turned 21 during study | .094 | .088 | 1.124 | 1.098 | .924 | 1.306 |

| Weekly drinking (T1) | .068 | .159 | .181 | 1.070 | .783 | 1.462 |

| Max eBAC (T1) | .180 | .112 | 2.590 | 1.198 | .962 | 1.492 |

| Preparty frequency (T1) | .389 | .135 | 8.311** | 1.476 | 1.133 | 1.923 |

| Drinks at last preparty (T1) | −.051 | .121 | .176 | .950 | .750 | 1.205 |

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 5.

Indirect effects for all model paths.

| Predictor | Mediator(s) | Outcome | Indirect Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 Prepartying Frequency | T2 Alcohol Approval → T2 Alcohol Consumption | T3 Consequences | 0.01, p=.038 |

| T1 Prepartying Frequency | T2 Alcohol Approval | T2 Alcohol Consumption | 0.01, p=.197 |

| T1 Prepartying Frequency | T2 Alcohol Consumption | T3 Consequences | 0.03, p=.015 |

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants R01AA12547 and R21AA021870 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism at the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Baer JS. Effects of college residence on perceived norms for alcohol consumption: An examination of the first year in college. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994;8(1):43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Blume AW, McKnight P, Marlatt GA. Brief intervention for heavy-drinking college students: 4-year follow-up and natural history. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(8):1310–1316. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Orchowski LM, Read JP, Kahler CW. Predictors and consequences of pregaming using day-and week-level measurements. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(4):921. doi: 10.1037/a0031402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry AE, Stellefson ML, Piazza-Gardner AK, Chaney BH, Dodd V. The impact of pregaming on subsequent blood alcohol concentrations: An event-level analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(8):2374–2377. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bem DJ. Self-perception: An alternative interpretation of cognitive dissonance phenomena. Psychological Review. 1967;74(3):183–200. doi: 10.1037/h0024835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bem DJ. Self-perception theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 1972;6:1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz AD. Higher Education Center for Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse and Violence Prevention. US Department of Education; 2004. The social norms approach: Theory, research and annotated bibliography; pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Two brief alcohol interventions for mandated college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19(3):296–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp JD, Reed MB, Min JW, Shillington AM, Croff JM, Holmes MR, Trim RS. Blood alcohol concentrations among bar patrons: A multi-level study of drinking behavior. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;102(1):41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(2):189–200. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie AM, Maggs JL, Lanza ST. Prepartying, drinking games, and extreme drinking among college students: a daily-level investigation. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;58(4):37–316. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio RH, Zanna MP, Cooper J. Dissonance and self-perception: An integrative view of each theory’s proper domain of application. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1977;13(5):464–479. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Vol. 2. Stanford University Press; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Foster JH, Ferguson C. Alcohol ‘pre-loading’: a review of the literature. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2013;49(2):213–226. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AL, Smith SK, Kagan K. Getting “game”: Pregaming changes during the first weeks of college. Journal of American College Health. 2013;61(2):95–105. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2012.753892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AL, Smith SK, Kagan K, Jacob T. Pre-college pregaming: Practices, risk factors, and relationship to other indices of problematic drinking during the transition from high school to college. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(4):931. doi: 10.1037/a0029765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009;76(4):408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe JM. Modeling Count Data. Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K, Anderson Z, Morleo M, Bellis MA. Alcohol, nightlife and violence: the relative contributions of drinking before and during nights out to negative health and criminal justice outcomes. Addiction. 2008;103(1):60–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer JF, Napper LE, Ehret PE, LaBrie JW. Event-specific risk and ecological factors associated with prepartying among heavier drinking college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(3):1620–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney SR, Hummer JF, LaBrie JW. An examination of prepartying and drinking game playing during high school and their impact on alcohol-related risk upon entrance into college. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(9):999–1011. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9473-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labhart F, Graham K, Wells S, Kuntsche E. Drinking before going to licensed premises: An event-level analysis of predrinking, alcohol consumption, and adverse outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37(2):284–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer J, Kenney S, Lac A, Pedersen E. Identifying factors that increase the likelihood for alcohol-induced blackouts in the prepartying context. Substance Use & Misuse. 2011;46(8):992–1002. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.542229). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Pedersen ER, Lac A, Chithambo T. Measuring college students’ motives behind prepartying drinking: Development and validation of the prepartying motivations inventory. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(8):962–969. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Anderson BK, Fader JS, Kilmer JR, Palmer RS, Cronce JM. Evaluating a brief alcohol intervention with fraternities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2001;62(3):370–380. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, … Williams E. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(4):604–615. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Couper MP, Crawford S, d’Arcy H. Mode effects for collecting alcohol and other drug use data: Web and US mail. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2002;63(6):755–761. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Vermont LN, Bachrach RL, Read JP. Is the pregame to blame? Event-level associations between pregaming and alcohol-related consequences. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74(5):757. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser K, Pearson MR, Hustad JT, Borsari B. Drinking games, tailgating, and pregaming: precollege predictors of risky college drinking. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40(5):367–373. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2014.936443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Statistical analysis with latent variables. User’s Guide,” Version. 2001;4 [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Dillard AJ, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, Neil TA. Normative misperceptions and temporal precedence of perceived norms and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(2):290–299. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(4):556–565. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, LaBrie J. Partying before the party: Examining prepartying behavior among college students. Journal of American College Health. 2007;56(3):237–245. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.3.237-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2002;(Supplement No 14):164–172. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Merrill JE, Bytschkow K. Before the party starts: Risk factors and reasons for “pregaming” in college students. Journal of American College Health. 2010;58(5):461–472. doi: 10.1080/07448480903540523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MB, Clapp JD, Weber M, Trim R, Lange J, Shillington AM. Predictors of partying prior to bar attendance and subsequent BrAC. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(12):1341–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl S, Sonntag T, Roehrig J, Kriston L, Berner MM. Characteristics of predrinking and associated risks: a survey in a sample of German high school students. International Journal of Public Health. 2013;58(2):197–205. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Davenport A, Rimm EB. A gender-specific measure of binge drinking among college students. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85(7):982–985. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1989;50(01):30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboanga BL, Schwartz SJ, Ham LS, Borsari B, Van Tyne K. Alcohol expectancies, pregaming, drinking games, and hazardous alcohol use in a multiethnic sample of college students. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2010;34(2):124–133. doi: 10.1007/s10608-009-9234-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]