Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the association between health insurance coverage and disease-modifying therapy (DMT) use for multiple sclerosis (MS).

Methods:

In 2014, we surveyed participants in the North American Research Committee on MS registry regarding health insurance coverage. We investigated associations between negative insurance change and (1) the type of insurance, (2) DMT use, (3) use of free/discounted drug programs, and (4) insurance challenges using multivariable logistic regressions.

Results:

Of 6,662 respondents included in the analysis, 6,562 (98.5%) had health insurance, but 1,472 (22.1%) reported negative insurance change compared with 12 months earlier. Respondents with private insurance were more likely to report negative insurance change than any other insurance. Among respondents not taking DMTs, 6.1% cited insurance/financial concerns as the sole reason. Of respondents taking DMTs, 24.7% partially or completely relied on support from free/discounted drug programs. Of respondents obtaining DMTs through insurance, 3.3% experienced initial insurance denial of DMT use, 2.3% encountered insurance denial of DMT switches, and 1.6% skipped or split doses because of increased copay. For respondents with relapsing-remitting MS, negative insurance change increased their odds of not taking DMTs (odds ratio [OR] 1.50; 1.16–1.93), using free/discounted drug programs for DMTs (OR 1.89; 1.40–2.57), and encountering insurance challenges (OR 2.48; 1.64–3.76).

Conclusions:

Insurance coverage affects DMT use for persons with MS, and use of free/discounted drug programs is substantial and makes economic analysis that ignores these supplements potentially inaccurate. The rising costs of drugs and changing insurance coverage adversely affect access to treatment for persons with MS.

Health care utilization is high in persons with multiple sclerosis (MS). Newly diagnosed individuals with MS are 3.5 times more likely to be hospitalized and have health care costs 4.7 times higher than healthy individuals.1 An important component of these costs is the use of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs).1 Although the number of DMTs with differing modes of administration and mechanisms of action has increased over time, accessibility of these therapies has become an increasing concern due to their high and rising costs.2

Health insurance assists with access to health care. Although most individuals with MS have health insurance,3 17.8% of participants with MS in a recent study reported that their insurance was worse in 2009 as compared to 12 months earlier.4 Due to the high cost of DMTs, private insurers and public insurance regulatory bodies often require individuals with MS to meet specific criteria to obtain coverage for these therapies,5 or require high copays.6 Such factors may prevent persons with MS and their physicians from making treatment decisions based on best evidence and patient preferences.7–9

The effect of health insurance coverage on the treatment choices made by persons with MS is poorly understood, particularly in the United States, where the health care climate has changed since the inception of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2012.10 Therefore, we evaluated the association between health insurance coverage and DMT use in a sociodemographically diverse MS population.

METHODS

Study population.

Participants in the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis Registry voluntarily report demographic and clinical information about their MS at enrollment and semiannually thereafter using paper or online questionnaires.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

Participants agree to the use of their information for research purposes. The registry is approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Information collected at enrollment includes sex, date of birth, race (dichotomized as Caucasian/non-Caucasian), marital status (dichotomized as married/not married), current employment status (full-time, part-time, unemployed), annual income (≤$30,000 USD, $30,001–$100,000 USD, >$100,000 USD), year of MS onset, age and year of MS diagnosis, type of MS (relapsing-remitting MS [RRMS], primary progressive MS [PPMS], and other), and level of disability reported using Patient-Determined Disease Steps (PDDS). The PDDS is an ordinal rating scale derived from Disease Steps, which ranges from 0 (no disability) to 8 (bedridden),11 and correlates highly with a physician-scored Expanded Disability Status Scale.12,13

Each semiannual survey reassesses level of disability; captures whether any DMTs were used in the last 6 months (yes/no) and the names of the DMT used; and updates sociodemographic information including marital status, employment status, and health insurance coverage (yes/no) including type (private, public, supplemental, and other).

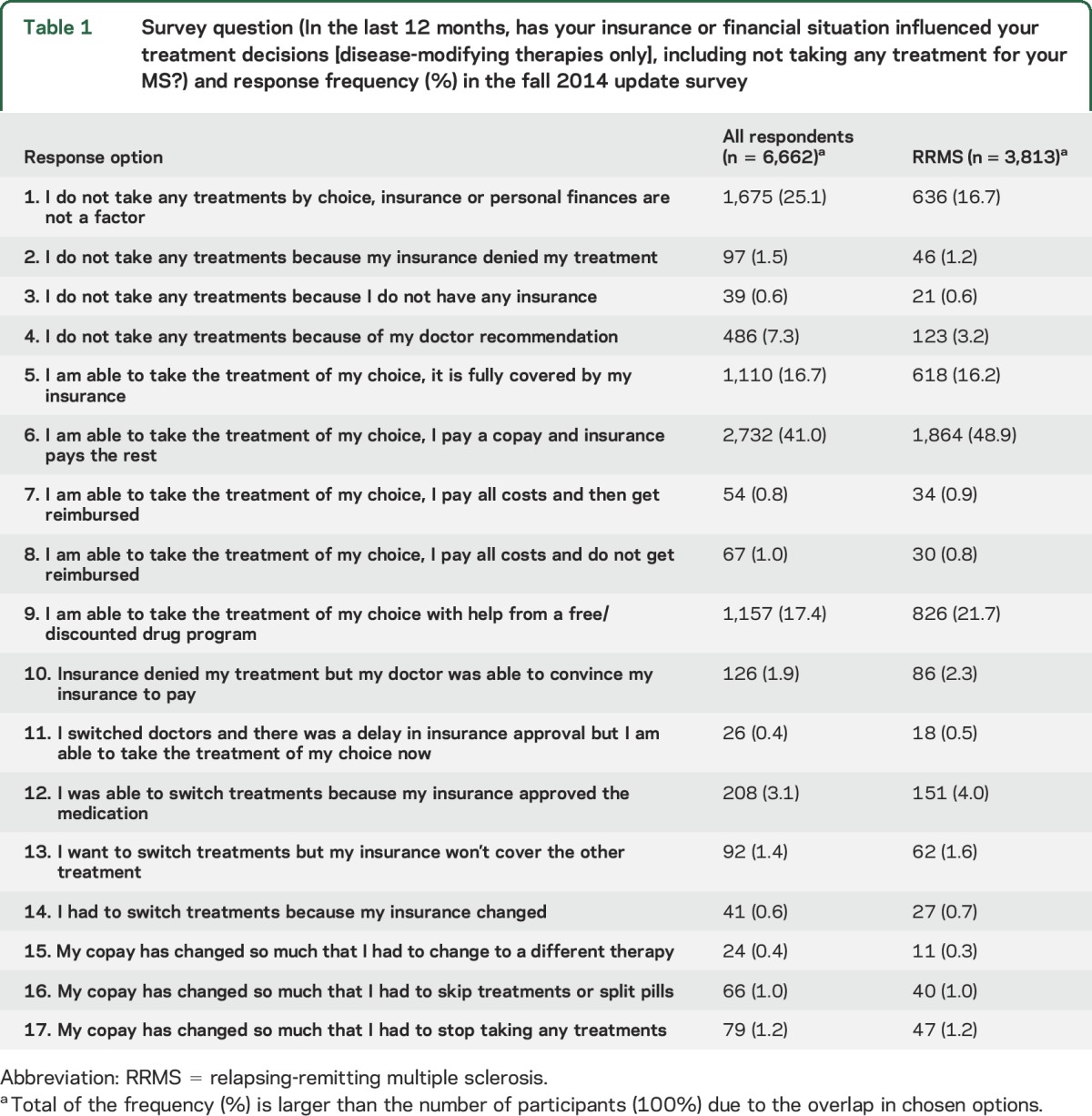

In the fall 2014 update survey, participants also reported whether health insurance coverage had been available for the entire 6 months preceding the survey (yes/no). They reported perceived change in their insurance compared with 12 months ago using a question adapted from Pozniak et al.4 with 4 response options: much better, somewhat better, remained unchanged, somewhat worse. Participants reported the influence of their insurance and financial situation on DMT choices in the last 12 months using a 17-option question (table 1).

Table 1.

Survey question (In the last 12 months, has your insurance or financial situation influenced your treatment decisions [disease-modifying therapies only], including not taking any treatment for your MS?) and response frequency (%) in the fall 2014 update survey

Analysis.

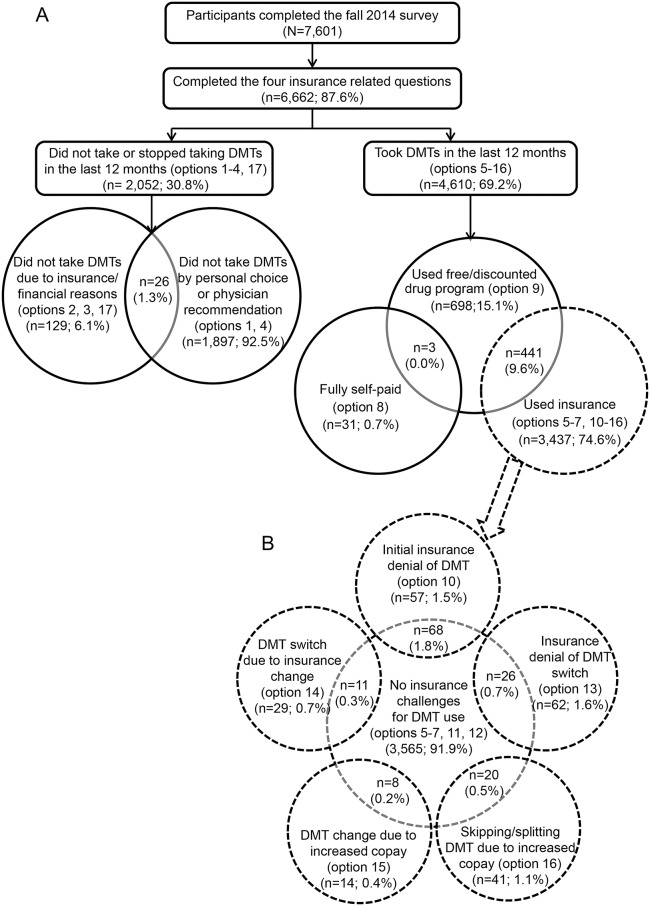

Only respondents who completed all insurance-related questions were included in the analysis. We divided the respondents into 2 categories based on their answers to the 17-option question (table 1, figure 1): (1) those who did not take or stopped taking DMTs in the last 12 months (checked any of options 1–4, or 17) (referred to as not taking DMT) and (2) those who took DMTs in the last 12 months (checked any of options 5–16) (referred to as taking DMT). For respondents who fell into both categories, we used their response to a separate question on DMT use in the last 6 months to ascertain final category placement where those reporting DMT use in the last 6 months were labeled as taking DMT and all others as not taking DMT.

Figure 1. Disposition of respondents by disease-modifying therapy (DMT) use and insurance challenges.

(A) Cohort disposition. (B) Distribution of respondents who took DMTs through insurance coverage by experienced insurance challenges. Total of the respondents (%) in (B) is greater than 100% due to overlap in the different types of challenges.

Within the not taking DMT category, we divided respondents into 2 groups by their reasons for not taking DMTs: (1) those who did not take DMTs by personal choice or physician recommendation (options 1 and 4) and (2) those citing insurance or financial reasons (options 2, 3, and 17). It was possible that some respondents decided not to take DMTs for multiple reasons, thus we allowed respondents to fall into both groups.

Within the taking DMT category, we divided respondents into 3 groups according to the financial resources used to pay for DMTs: (1) self-pay only (no insurance); (2) free or discounted drug programs; and (3) insurance. It was reasonable that some respondents obtained DMTs using multiple resources concurrently, thus overlap between groups 1 and 2 or groups 2 and 3 was allowed. However, overlap between groups 1 and 3 was not allowed; those who fell into both groups 1 and 3 were assigned into group 3 only. Due to the small number of respondents in group 1 (n = 34), only respondents in groups 2 and 3 were used for statistical inference.

We partitioned respondents who obtained DMTs through insurance into 6 groups by whether or not they encountered any challenges from their insurance for DMT use: (1) no challenges from insurance for DMT use (options 5–7, 11, 12); (2) initial insurance denial of DMT (option 10); (3) insurance denial of DMT switch (option 13); (4) DMT switch due to insurance change (option 14); (5) DMT change due to increased copay (option 15); and (6) skipping or splitting DMTs due to increased copay (option 16). Belonging to multiple groups was allowed. Respondents with any insurance challenge were grouped together and compared to those without insurance challenge. We grouped respondents' health insurance into 4 mutually exclusive groups: only public, only private, public and private, and public+ (public insurance + supplemental/other insurance).

We characterized the study cohort using descriptive statistics and used Pearson χ2 to compare the proportions of categorical variables, analysis of variance to test normally distributed continuous variables, and nonparametric Wilcoxon or Kruskal to test non-normally distributed continuous variables or ordinal variables. We dichotomized respondents' insurance change compared with 12 months ago as negative insurance change (somewhat worse) and stable insurance (remained unchanged, somewhat better, and much better). The association between negative insurance change and (1) type of insurance, (2) DMT use, (3) use of free or discounted drug programs, or (4) insurance challenges was investigated using multivariable logistic regression analyses14 adjusting for potential confounders including age at the time of survey, PDDS, disease duration, annual income, marital status, disability status, and employment status in the last 6 months and for type of insurance (for outcomes 2, 3, and 4). We initially conducted analyses for all respondents and then repeated our analyses limited to RRMS respondents since the clinical trials leading to DMT approval only enrolled persons with RRMS.15

All p values were based on 2-sided tests and values <0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Of the 12,492 active participants invited to complete the fall 2014 update survey, 7,601 (60.9%) completed the survey, of whom 6,662 (87.6%) completed all insurance-related questions and were included in this study. As compared to respondents, nonrespondents were younger (table e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org). Respondents included in the study were more likely to be female, to be younger at the time of survey, to have a higher income and shorter disease duration, and to have RRMS compared to those not included (table e-1).

Perceived insurance change.

Of the 6,662 respondents analyzed, 6,562 (98.5%) reported being insured for the entire prior 6 months, 4,621 (69.4%) reported that their insurance remained unchanged, and 1,472 (22.1%) reported worse insurance compared to 12 months ago. Of the 3,813 respondents with RRMS, 3,749 (98.3%) reported being insured in the entire prior 6 months, 2,565 (67.3%) reported that their insurance remained unchanged, and 918 (24.1%) reported worse insurance. Compared to those with RRMS, the 2,849 respondents with other forms of MS were less likely to report worse insurance (19.5%, p < 0.0001) despite the similar frequency (98.8%) of being insured.

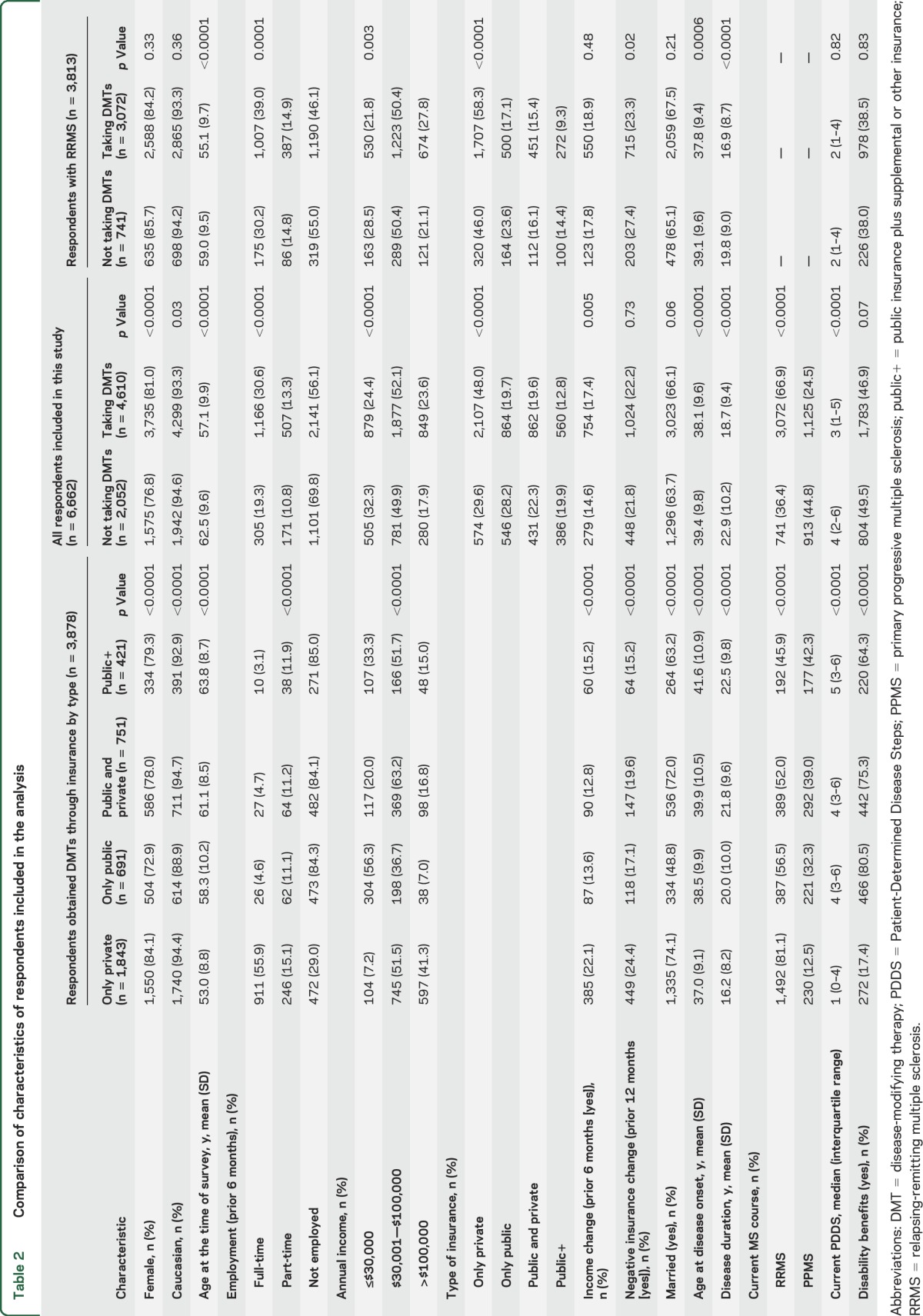

Of the 6,662 respondents, 2,681 (42.3%) reported having only private insurance, 1,410 (22.3%) only public, 1,293 (20.4%) public and private, and 946 (14.9%) public+. Among respondents who obtained DMTs through insurance coverage, those with only private insurance tended to be younger, employed, and less disabled, with higher income, shorter disease duration, RRMS, and lower PDSS than those in the other groups (table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of characteristics of respondents included in the analysis

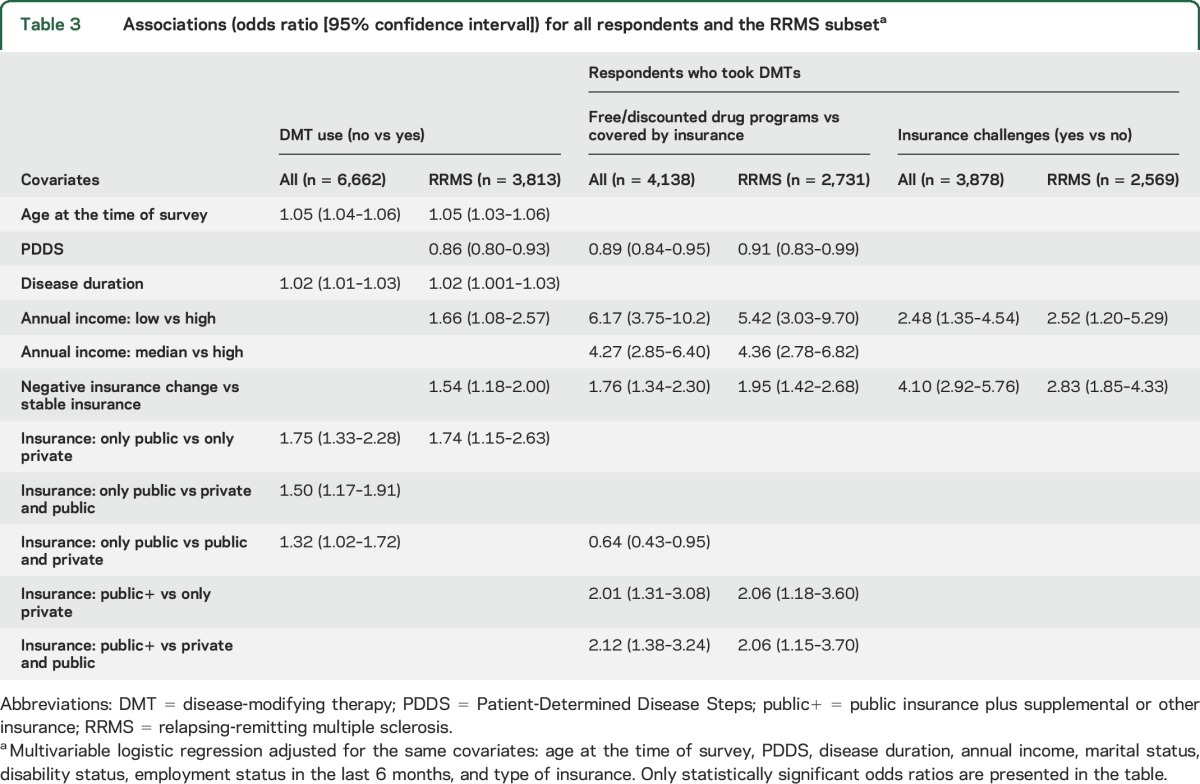

Among those with only private insurance, 710 (26.5%) reported negative insurance change vs 263 (20.3%) with only public, 254 (18.1%) with public and private, and 152 (16.1%) with public+. Negative insurance change was only associated with disability status (p = 0.03) and the type of insurance (p < 0.0001). Respondents with only private insurance were more likely to report negative insurance changes compared to those with only public (odds ratio [OR] 2.00; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.43–2.81), public and private (OR 1.59; CI 1.19–2.11), and public+ (OR 1.75; CI 1.31–2.35).

Negative insurance change and DMT use.

Among all respondents, 4,610 (69.2%) took DMTs (figure 1A), as did 3,072 (80.6%) of the RRMS respondents (figure e-1a). Respondents not taking DMTs were more likely to be older, unemployed, and male, with lower incomes, longer disease durations, and more severe disability, and to have PPMS compared to those taking DMTs (table 2). Similar findings were observed among those with RRMS (table 2). The association between negative insurance change and DMT use was not statistically significant among the 6,662 respondents, but was among the RRMS respondents (table 3). After adjustment, the odds of not taking DMTs for RRMS respondents with negative insurance change were higher than for those with stable insurance, and were higher for those with only public insurance compared to those with only private insurance (table 3).

Table 3.

Associations (odds ratio [95% confidence interval]) for all respondents and the RRMS subseta

Reasons for not taking DMT.

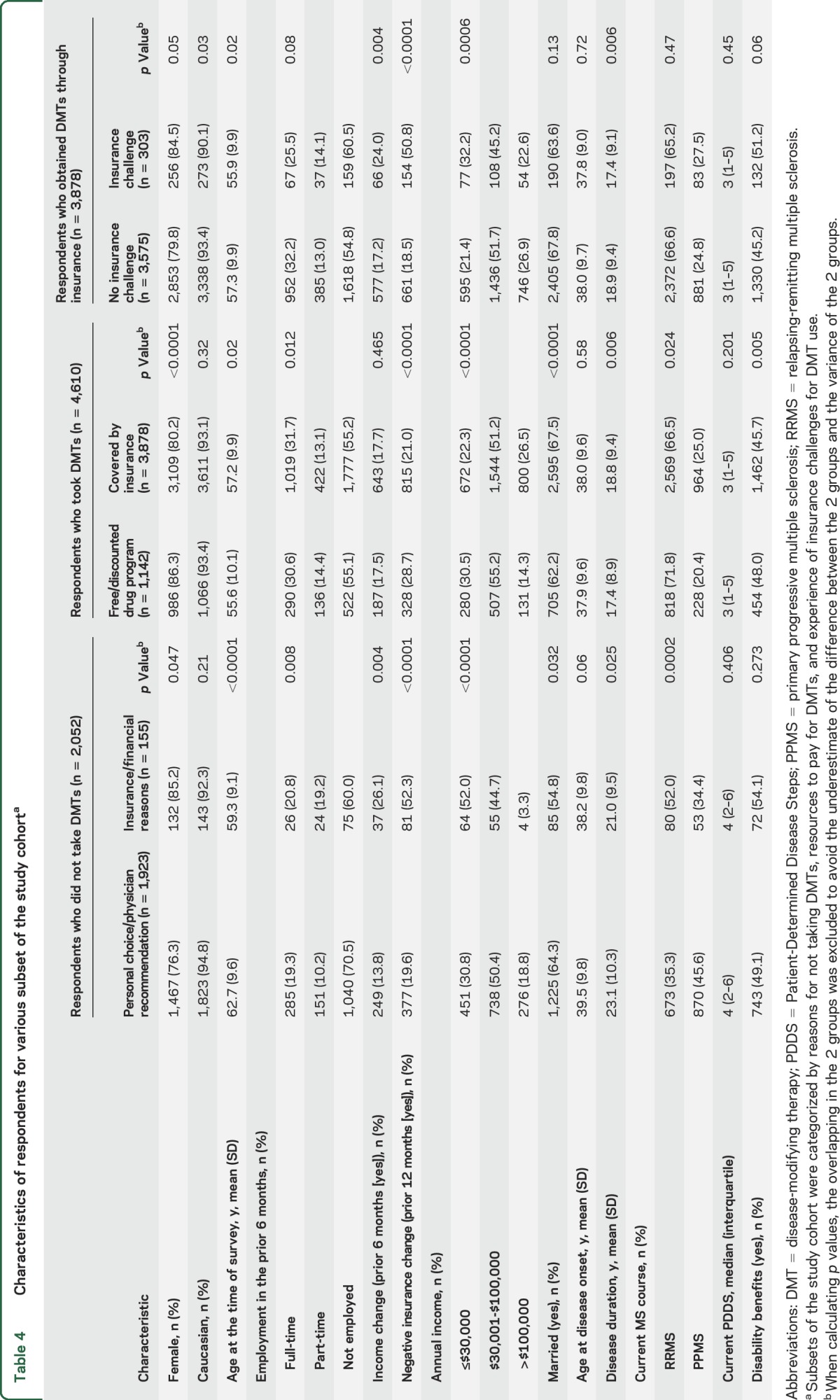

Among respondents not taking DMTs, most did not take DMTs by personal choice, physician recommendation, or both. However, 6.1% were unable to take DMTs solely due to insurance or financial reasons (figure 1A). This increased to 9.2% when restricted to RRMS (figure e-1a). As compared to respondents who did not take DMTs by choice or physician recommendation, those who did not take DMTs for insurance reasons were more likely to be women, younger at the time of survey, and employed, with lower incomes, to have experienced an income change in the prior 6 months, to have RRMS, and to report a negative insurance change (table 4). When analyses were restricted to RRMS, similar findings were observed (table e-2).

Table 4.

Characteristics of respondents for various subset of the study cohorta

Negative insurance change and the use of free or discounted drug programs.

Among respondents taking DMTs, about three-quarters obtained DMTs solely through insurance, while 15.1% completely and 9.6% partially used free or discounted drug programs (figure 1A). As compared to those who obtained DMTs through insurance, those who utilized free or discounted drug programs were more likely to be female, younger at the time of survey, and not married, and to report negative insurance change, to have shorter disease durations, and to experience RRMS (table 4). After adjustment, the odds of using free or discounted drug programs were higher for those with negative insurance change than those with stable insurance and for those with public+ insurance compared to those with only private or private and public (table 3). When restricted to RRMS respondents, the findings were similar (tables 3 and e-2).

Negative insurance change and ongoing DMT use.

Although most of the 3,878 respondents who obtained DMTs through insurance did not report any insurance challenges related to their DMT use in the last 12 months, insurance challenges were not rare. For example, 125 (3.3%) respondents reported that their insurance initially denied their DMT use but their physicians were able to convince their insurance provider to pay, 88 (2.3%) reported that their insurance provider denied the request to switch DMTs, and 61 (1.6%) had to skip or split doses due to increased copay (figure 1B). Some respondents encountered insurance challenges during only part of the 12-month period. Overall, 303 (7.8%) respondents reported at least one insurance challenge. Compared to respondents who never encountered insurance challenges for DMT use, those with insurance challenges were younger at the time of survey and more likely to have income change, negative insurance change, lower incomes, and shorter disease durations (table 4). When restricted to RRMS respondents, the only persistent difference was in the proportion with negative insurance change (19.8% for those without insurance challenges vs 48.2% for those with). After adjustment, the odds of encountering insurance challenges for DMT use for respondents with negative insurance change were higher than those with stable insurance regardless of MS type (table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this study of 6,662 persons with MS in the United States, we found that although most individuals had health insurance, over 20% reported that their insurance coverage had worsened over the last 12 months. This worsening may underestimate the proportion with coverage changes, since changes in insurance coverage often occur annually and our survey would capture some participants before an impending change is recognized. Among respondents who did not take DMTs, over 6% reported the sole reason to be financial or insurance concerns. Of respondents taking DMTs, nearly 25% relied on at least partial support from free or discounted drug programs. Of respondents who obtained DMTs through insurance, more than 3% experienced initial insurance denial of DMT use, over 2% encountered an insurance denial on DMT switch, and nearly 2% had to skip or split doses because of increased copays.

We employed a similar question to another study, and our estimate of the proportion of respondents who reported that their insurance coverage was worse is about 4% higher than reported previously.4 The slight difference may reflect differences in study cohorts or time periods. Our study had nearly 3 times as many respondents and our respondents had longer disease duration and lower annual income. The study by Pozniak et al.4 was conducted 5 years earlier than ours, which was conducted over 6 months after the ACA took effect.10

Respondents with private insurance were more likely to report negative insurance change. Financial burden and lack of insurance coverage of DMT use directly affected access to any DMT for a large number of respondents and posed challenges for respondents and their physicians with respect to the choice of DMT. As expected, negative insurance change affected persons with RRMS more than those without RRMS since the available DMTs mainly target RRMS. These negative effects likely reflect the dramatically increased cost of DMTs and the response to those high costs by insurance carriers.2 However, the cross-sectional study design prevents us from confirming the conjecture that initial denial of coverage for DMTs occurred more frequently now than previously for new and established patients.2 One encouraging observation in our study is that respondents who encountered initial insurance denials of DMTs also reported that their doctors usually were able to obtain coverage by the insurance carriers for the desired treatment. This highlights the important role physicians play in maintaining patient access to DMTs.2

It is uncertain whether the extensive use of free or discounted drug programs reflects that a preferred DMT was not covered by insurance or whether copays were too high, but suggests an important gap between health insurance needs and current coverage. While negative insurance changes may explain the gap for some individuals, the recognized rise in the cost of DMTs is likely to be another substantial contributing factor.2 If the costs of DMTs continue to rise as they have over the last 5 years, we can expect that they will become unattainable for many individuals with MS. Further, economic studies that fail to incorporate information on subsidized drugs may come to inaccurate conclusions when doing cost-effectiveness analyses.

We found that the financial burden of DMTs also reduced the ability of persons with MS to adhere to therapy as manifest by skipping doses, further reducing the benefit from these therapies. Nonadherence increases the risk for MS-related hospitalization, relapse, and medical costs.16 Other authors have reported that over 40% of persons with MS were not adherent to DMTs, with barriers including depression, cognitive impairment, perceived lack of efficacy, adverse events, inconvenience of injection, and needle phobia.16,17 The cost of medications contributes importantly to nonadherence,18,19 and we have shown that this is a specific concern in the MS population, which may worsen as the costs of DMTs rise. Future studies should seek to understand the relative importance of, and interplay between, all of these factors in nonadherence and how they vary across health systems.

The potential limitations of this study include self-report bias, recall bias, and the selection biases inherent in a self-report registry.20 Additionally, the dynamic nature of insurance and the limitation of cross-sectional studies make it difficult to investigate the reasons for insurance challenges and for the extensive use of free or discounted drug programs. We do not know whether participants considered copay support to be a form of discounted medication, thus we may have underestimated the degree of financial support provided by pharmaceutical companies. We focused on access to DMTs as they are very costly, but access to symptomatic therapies, durable medical equipment, and other health services are also relevant, as is the cost of health insurance itself. Nonetheless, the suggestion of an increasing trend implied by the large percentage of respondents who reported negative insurance change is important.

Although more DMTs have emerged over the last few years, the costs of these therapies are a substantial impediment to their use.2 As DMTs become more costly, given the poor quality of some insurance coverage, it will be increasingly difficult for persons with MS to avail themselves of this treatment option without additional supports such as free or discounted drug programs. Among those with RRMS, young women and individuals with lower incomes are less likely to use these therapies. Action is needed to ensure that all individuals eligible for DMT, including groups for which therapies are newly emerging such as PPMS, are able to benefit from these therapies if they and their physicians deem it to be the best course of action.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- ACA

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

- CI

confidence interval

- DMT

disease-modifying therapy

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- OR

odds ratio

- PDDS

Patient-Determined Disease Steps

- PPMS

primary progressive multiple sclerosis

- RRMS

relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

Editorial, page 346

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Gary R. Cutter conceived of the idea and designed the study. Guoqiao Wang conducted the analyses and drafted the manuscript. Ruth Ann Marrie drafted the manuscript. Amber R. Salter, Gary R. Cutter, Robert Fox, Stacey S. Cofield, and Tuula Tyry edited the manuscript. All authors approved of the version to be published.

STUDY FUNDING

NARCOMS is supported in part by the Consortium of MS Centers and its Foundation. This study was supported in part by the Foundation of the CMSC and an unrestricted educational grant by Biogen (to G.W.) and by a Don Paty Career Development award from the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada (to R.A.M.) and Manitoba Research Chair from Research Manitoba (to R.A.M.).

DISCLOSURE

G. Wang: The NARCOMS Research Fellowship is supported in part by the Foundation of the CMSC and an unrestricted educational grant by Biogen. R. Marrie receives research funding from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Research Manitoba, Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada, Multiple Sclerosis Scientific Foundation, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and Rx & D Health Research Foundation, and has conducted clinical trials funded by Sanofi-Aventis. A. Salter reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. R. Fox received personal consulting fees from Biogen Idec, Genentech, Mallinckrodt, MedDay, Novartis, Teva, and XenoPort. Robert Fox has served on advisory committees for Biogen Idec and Novartis and received research grant funding from Novartis. S. Cofield received consulting fees for American Shoulder and Elbow Society; DMSB service MedImmune, Inc.; and grant reviews for Department of Defense. T. Tyry reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. G. Cutter: consulting and/or DSMB commitments in the last 12 months. Participation of Data and Safety Monitoring Committees: All of the below organizations are focused on medical research. Apotek; Biogen-Idec; Cleveland Clinic (Vivus); Glaxo Smith Klein Pharmaceuticals; Gilead Pharmaceuticals; Modigenetech/Prolor; Merck/Ono Pharmaceuticals; Merck; Merck/Pfizer; Neuren; Sanofi-Aventis; Teva; NHLBI (Protocol Review Committee); NINDS; NICHD (OPRU oversight committee). Consulting, speaking fees, and advisory boards: Consortium of MS Centers (grant); D3 (Drug Discovery and Development); Genzyme; Janssen Pharmaceuticals; Klein-Buendel Incorporated; Medimmune; Novartis; Opexa Therapeutics; Receptos; Roche EMD Serono; Spiniflex Pharmaceuticals; Teva Pharmaceuticals; Transparency Life Sciences. Dr. Cutter is employed by the University of Alabama at Birmingham and President of Pythagoras, Inc., a private consulting company located in Birmingham, Alabama. Data and Safety Monitoring Boards: Apotek, Biogen-Idec, Cleveland Clinic (Vivus), Glaxo Smith Klein Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Pharmaceuticals, Modigenetech/Prolor, Merck/Ono Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Merck/Pfizer, Neuren, Sanofi-Aventis, Teva, Washington University, NHLBI (Protocol Review Committee), NINDS, NICHD (OPRU oversight committee). Consulting or advisory boards: Consortium of MS Centers (grant), D3 (Drug Discovery and Development), Genzyme, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Klein-Buendel Incorporated, Medimmune, Novartis, Opexa Therapeutics, Receptos, Roche, EMD Serono, Teva pharmaceuticals, Transparency Life Sciences. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asche CV, Singer ME, Jhaveri M, Chung H, Miller A. All-cause health care utilization and costs associated with newly diagnosed multiple sclerosis in the United States. J Manage Care Pharm 2010;16:703–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartung DM, Bourdette DN, Ahmed SM, Whitham RH. The cost of multiple sclerosis drugs in the US and the pharmaceutical industry: too big to fail? Neurology 2015;84:2185–2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whetten-Goldstein K, Sloan FA, Goldstein LB, Kulas ED. A comprehensive assessment of the cost of multiple sclerosis in the United States. Mult Scler 1998;4:419–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pozniak A, Hadden L, Rhodes W, Minden S. Change in perceived health insurance coverage among people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care 2014;16:132–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hohol M, Orav E, Weiner H. Disease steps in multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study comparing disease steps and EDSS to evaluate disease progression. Mult Scler 1999;5:349–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L, Hoaglin D. Access to health care for people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2007;13:547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karussis D, Biermann L, Bohlega S, et al. A recommended treatment algorithm in relapsing multiple sclerosis: report of an international consensus meeting. Eur J Neurol 2006;13:61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Río J, Comabella M, Montalban X. Multiple sclerosis: current treatment algorithms. Curr Opin Neurol 2011;24:230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vosoughi R, Freedman MS. Therapy of MS. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2010;112:365–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Public Law 2010. No. 124:111–148. Stat. 382 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hohol M, Orav E, Weiner H. Disease steps in multiple sclerosis: a simple approach to evaluate disease progression. Neurology 1995;45:251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marrie RA, Goldman M. Validity of performance scales for disability assessment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2007;13:1176–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Learmonth YC, Motl RW, Sandroff BM, Pula JH, Cadavid D. Validation of Patient Determined Disease Steps (PDDS) scale scores in persons with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol 2013;13:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosmer DW Jr, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wingerchuk DM, Carter JL. Multiple sclerosis: current and emerging disease-modifying therapies and treatment strategies. Mayo Clinic Proc 2014;89:225–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan H, Cai Q, Agarwal S, Stephenson JJ, Kamat S. Impact of adherence to disease-modifying therapies on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with multiple sclerosis. Adv Ther 2011;28:51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patti F. Optimizing the benefit of multiple sclerosis therapy: the importance of treatment adherence. Patient Prefer Adherence 2010;4:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y. Prescription drug cost sharing: associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA 2007;298:61–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rector TS, Venus PJ. Do drug benefits help Medicare beneficiaries afford prescribed drugs? Health Aff 2004;23:213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahajan S, Patel P, Marrie R. Under treatment of overactive bladder symptoms in patients with multiple sclerosis: an ancillary analysis of the NARCOMS Patient Registry. J Urol 2010;183:1432–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.