Abstract

Background:

Scar formation after injury or surgery is a major clinical problem. Individually, hyaluronan, or hyaluronic acid (HA), and vitamin C have been shown to reduce scarring by means of different mechanisms. The authors evaluated the efficacy and safety of an HA sponge system containing an active derivative of vitamin C to determine whether the use of this product promotes healing and reduces inflammation and scarring after surgery.

Methods:

This double-blind, randomized, prospective study was approved by the local institutional review board. Participants who had unilateral or bilateral surgical scars more than 1 month but less than 18 months old were enrolled. Surgical scars were randomly assigned to receive placebo or HA sponge with vitamin C. Three blinded evaluators reviewed photographs of the incision lines and assessed the scars using a visual analog scale. A patient satisfaction survey was also administered. Participants were followed up at 4 weeks, 12 weeks, and 1 year.

Results:

Twenty-three patients were enrolled in the study. Six patients dropped out of the study, for a total of 17 patients included in final analysis. Mean (range) age of patient was 43.5 (25–67) years. Mean (range) body mass index was 27.4 (18–36.9) kg/m2. The mean visual analog scale score for scars receiving HA sponge with vitamin C was slightly lower than the scars receiving placebo, but the difference was not statistically significant (t test; P = 0.9). The HA sponge with vitamin C was found to have significant positive findings on a patient satisfaction survey.

Conclusions:

The HA sponge system with vitamin C is safe to use in any scars older than 4 weeks. It has high patient satisfaction in achieving a better scar after surgery. The micro-roller used to apply the product was easy to use to potentially increase the spread of the medication in older scars.

Scar formation after injury or surgery is a major clinical problem leading to functional disability (contractures, adhesions) and disfigurement. Scar contracture, hypertrophic scar, or keloid can lead to physical deformities, which can be disabling.1 The annual economic burden of this problem has been conservatively estimated at more than $4 billion in the United States. Each year, 100 million US patients acquire scars as a result of surgical procedures, with approximately 55 million elective operations and 25 million operations after trauma performed annually.2 Scar management strategies have traditionally focused on the biologic components of wound healing with the goal of identifying a single gene or transcription factor responsible for scar formation. To date, however, such strategies have not been successful.1,3

Skin repair after injury in adult humans follows 4 distinct phases: homeostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling.4 Primary, secondary, and tertiary stages of wound healing occur simultaneously in differing degrees of intensity; it is important for wounds to go through all 3 healing stages for the resultant scar to be aesthetically pleasing.3–6

Three main areas of scar control are scar support to decrease skin tension, hydration, and accelerated scar maturation. Scar support during the maturation phase, which starts at 3 weeks and can last for years, has been studied for years with various available commercial products,7 but no product has been found to provide optimal standard outcomes over various skin types and scar types. Silicon sheeting is one commonly used product which provides hydration, and negative charge and occlusion of the scar, as a mechanism of action, but there is no clear support that this product will actually modulate inflammation and intrinsic factors of scar maturation.8,9

Scarless fetal healing is thought to be influenced by the abundance of hyaluronic acid (HA),10 which has been shown to modulate inflammation.11 On the contrary, we have limited knowledge about its exact mechanism of action in accelerating scar maturation and improvement of the appearance of scars.12,13 Although scar maturation can be accelerated by conversion of immature collagen to mature collagen, other factors that modulate inflammation and control the orientation of collagen fingers may play a role in overall aesthetic appearance of the scars.3,5,6,13–16

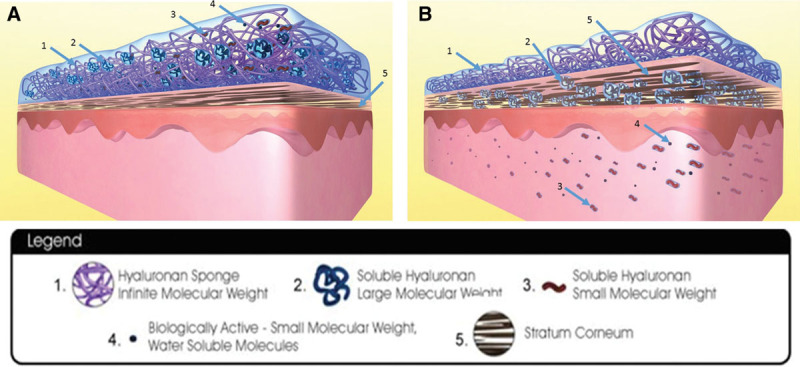

One scar management product, the hyaluronan or HA sponge (HylaSponge System, Matrix Biological Institute, Fort Lee, N.J.), uses polymerization methods to produce a network of small and large HA molecular chains bound into large coils (Fig. 1). These coils form spheroidal particles that can absorb and release large volumes of water or water-soluble molecules. This process in turn improves hydration and other mechanisms of a more desirable scar maturation such as delivering HA molecules and other water-solvable molecules to the scar.17

Fig. 1.

Hyaluronan sponge system. A, Hyaluronan sponge system with soluble hyaluronan large molecular weight, soluble hyaluronan small molecular weight, and biologically active molecule still within the sponge system. Stratum corneum is not hydrated and thinner. B, Hyaluronan sponge system with soluble hyaluronan large molecular weight, soluble hyaluronan small molecular weight, and biologically active molecule transferred into the layers of skin. Surface of skin and skin layers are kept hydrated by this mechanism. Stratum corneum is well hydrated and thicker. Reprinted with permission from Hylaco LLC.

Vitamin C plays a very important role in collagen metabolism. Magnesium ascorbyl phosphate (MAP) is a water-soluble, nonirritating, stable derivative of vitamin C. It has the same potential as vitamin C to boost skin collagen synthesis, but it is effective in significantly lower concentrations and can be used at concentrations as low as 10% to suppress melanin formation (in skin-whitening solutions). Of note, MAP may be a better option than vitamin C for persons with sensitive skin and those wishing to avoid any exfoliating effects, as many vitamin C formulas are highly acidic (and therefore produce exfoliating effects).18 Skin enzymes transform MAP into ascorbic acid (vitamin C), an antioxidant and a cofactor for an enzyme essential in the synthesis of collagen. As an antioxidant, vitamin C scavenges and destroys reactive oxidizing agents and other free radicals. It can thus provide important protection against damage induced by ultraviolet radiation (and the DNA mutations and cancer that may result from it).19 Vitamin C also helps to improve skin elasticity, decreases wrinkles by stimulating collagen synthesis, reduces redness, promotes wound healing, and suppresses cutaneous pigmentation. Because body control mechanisms limit the amount of ingested vitamin C available to the skin, topical application is an efficient way to target vitamin C antioxidant therapy directly to the skin. This topical antioxidant is a more stable form of ascorbic acid that can stimulate collagen synthesis.18,20–23

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of an HA sponge system containing MAP (ie, HA sponge with vitamin C). We sought to determine whether the use of this product promotes healing and reduces inflammation and scarring after surgery.

METHODS

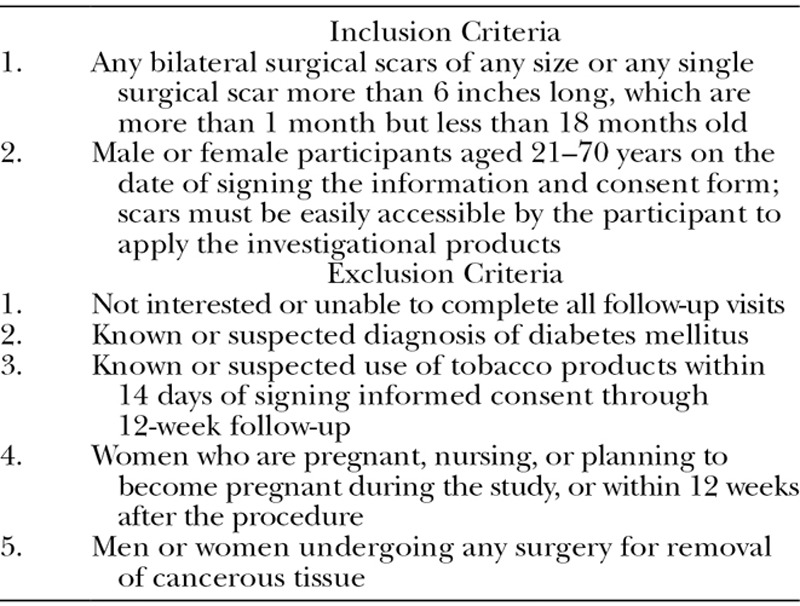

The present double-blind, randomized, prospective study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School. Participants were surgical patients who had unilateral or bilateral surgical scars more than 1 month but less than 18 months old. Complete inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible participants were randomly assigned to group 1 or group 2. SAS PROC PLAN software (SAS software version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.) was used to generate random sequence of assignments. Then, series of numbered envelopes were prepared, each containing a treatment assignment for the next participant. Patients who were eligible for the study were given sequential subject ID, which was matched with a number on randomization envelopes. Envelope was then opened by a research nurse, and patients received investigational or placebo based on treatment assignment in envelope. Each product was marked only as “product A” and “product B.” For unilateral incisions, participants in group 1 applied HA sponge with vitamin C (investigational, product A) to the right side of the scar and placebo (product B, formulation without active ingredients) to the left side of the scar. Patients were blinded as to which region of the scar received the active product and placebo. For bilateral incisions, participants in group 1 applied HA sponge with vitamin C to the right scar and placebo to the left scar.

For unilateral incisions, participants in group 2 applied placebo to the right side of the scar and HA sponge with vitamin C to the left side of the scar; for bilateral incisions, participants in group 2 applied placebo to the right scar and HA sponge with vitamin C to the left scar.

Product A—Intensive repair and Protect Vitamin C—Water, HylaSponge System, Magnesium ascorbyl phosphate, Acetyl hexapeptide-3, Glycerin, Citric acid, Palmitoyl tripeptide-5, Hydrolyzed Jojoba Protein, Benzylalcohol/Dehydroacetic acid, Aloe barbadensis, Xanthan gum, Disodium EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), Fragrance oil.

Product B—Formulation without active ingredients: Water, Xanthan gum, EDTA, Benzylalcohol-DHA, TEA (Triethylamine), fragrance oil.

Products were supplied and packaged identically by the sponsor and labeled “product A” and “product B” so that the investigator, the research team, and the participants were unable to distinguish which product was applied to which area. Participants were instructed to apply the products twice daily to each side or equally divided single area.

Participants were in the active treatment phase of the study for 12 weeks with 4 study visits (screening, 4 weeks, 12 weeks, and 1 year). After 12 weeks, participants received the HA sponge with vitamin C and micro-rollers (stainless steel, 0.25 microns) to use on both sides or incisions until the 1-year visit. Each visit included evaluation by the investigator, patient satisfaction surveys, and photographs of the surgical sites. Three blinded evaluators reviewed the photographs and assessed the scars with a Modified Manchester/visual analog scale (VAS) at 12 weeks. A 10-point New Scale was created by adding measures including scar color, texture, relation to surrounding skin, and distortion. For all scales, lower scores indicated better outcomes.

Group comparison for all variables considered ordinal and not normally distributed was analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test. For comparisons of continuous variables, a 2-group t test was used. Categorical variables were analyzed using a χ2 test or the Fisher exact test. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. For multiple tests within a single table comparison, appropriate adjustments to the P values were made using a Bonferroni technique. The χ2 test was also used in statistical analysis. Statistical tests were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.3; SAS Institute).

RESULTS

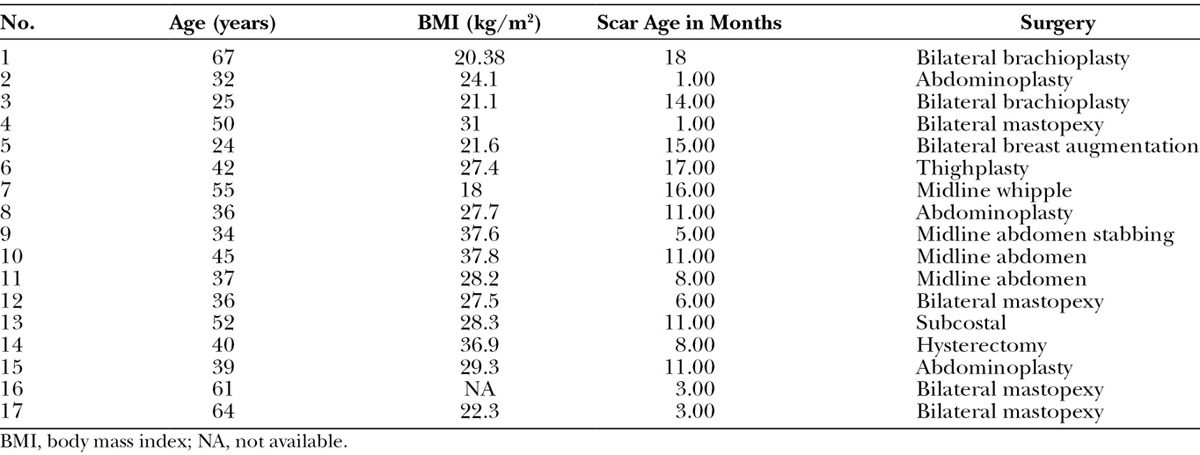

A total of 24 patients were enrolled in the study. Seven patients dropped out of the study, for a total of 17 patients included in final analysis. Six patients were lost to follow-up and 1 patient withdrew consent after initially getting enrolled in the study because of personal reasons. Mean (range) age of was 43.5 (25–67) years. Mean (range) body mass index was 27.4 (18–36.9). Mean (range) scar age was 21.4 (1–18.5) months. Exception was made for 1 patient with follow-up few months later (18.5 months) as it did not affect the result of the study. Patient demographics are shown in Table 2. No adverse effects were reported in any patients.

Table 2.

Patient Demographics

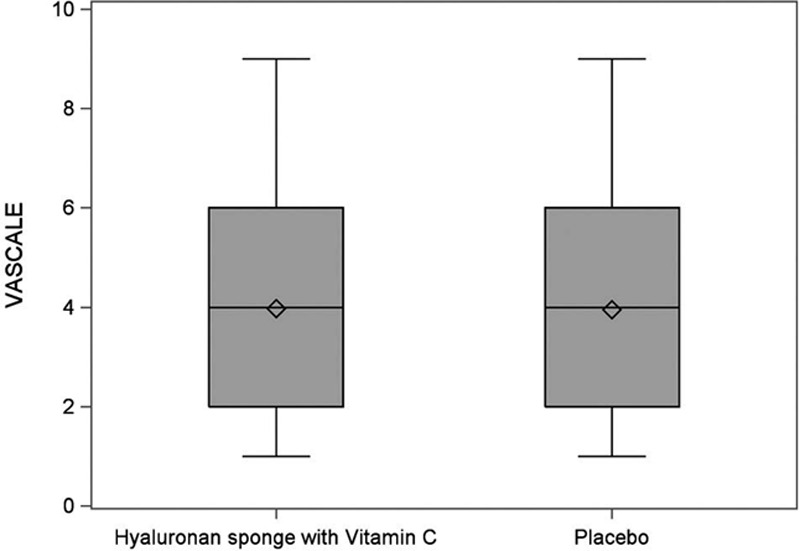

Figure 2 shows the analysis of VAS at 12 weeks. It shows the agreement comparing sides that received the HA sponge with vitamin C versus placebo on the same participant. The mean VAS score for the HA sponge with vitamin C side (3.98) is very close to the placebo side (3.96) with no statistically significant difference (t test; P = 0.9).

Fig. 2.

Visual analog scale score analysis at 12 weeks.

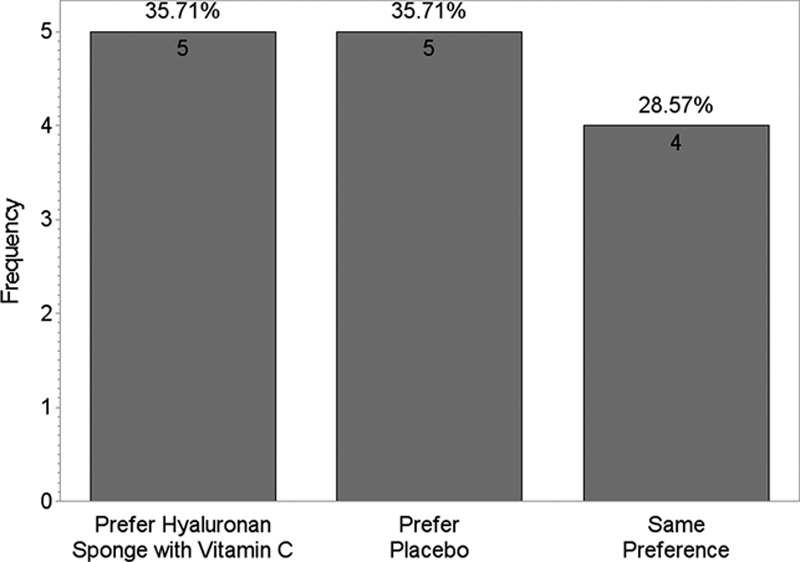

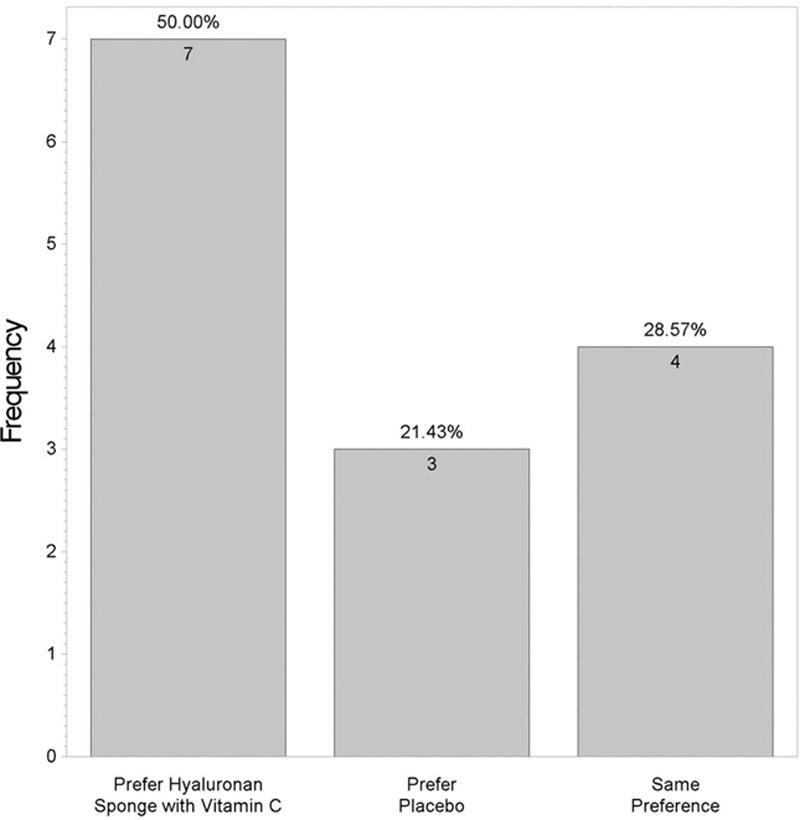

Figures 3 and 4 show that differences were found between the 2 products for questions like “Which scar is smoother?” (P = 0.93) and “Which product do you prefer?” (P = 0.4). These were not statistically significant.

Fig. 3.

Product preference based on smoothness.

Fig. 4.

Which side do you prefer?

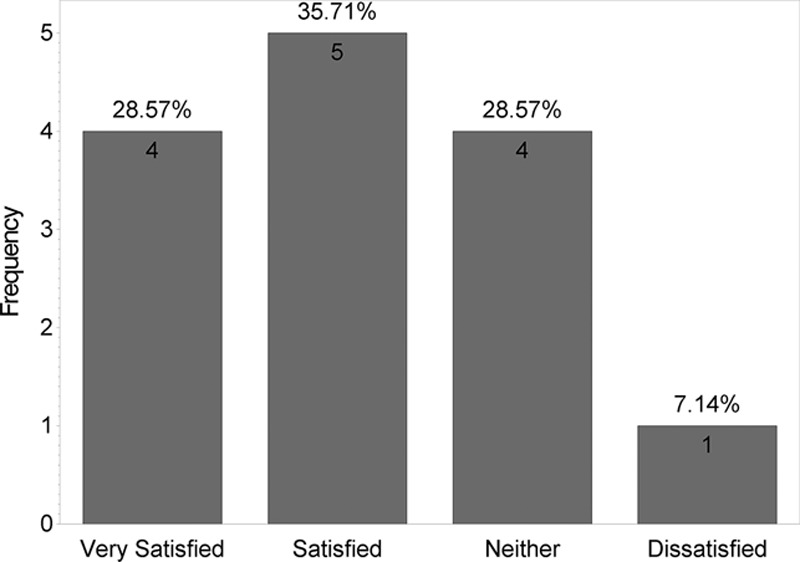

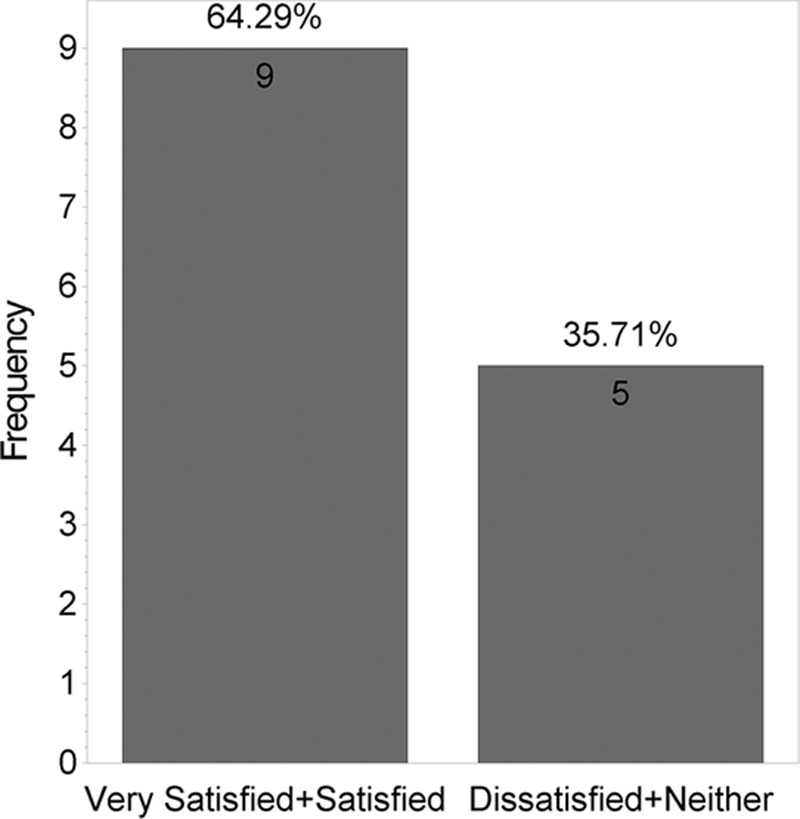

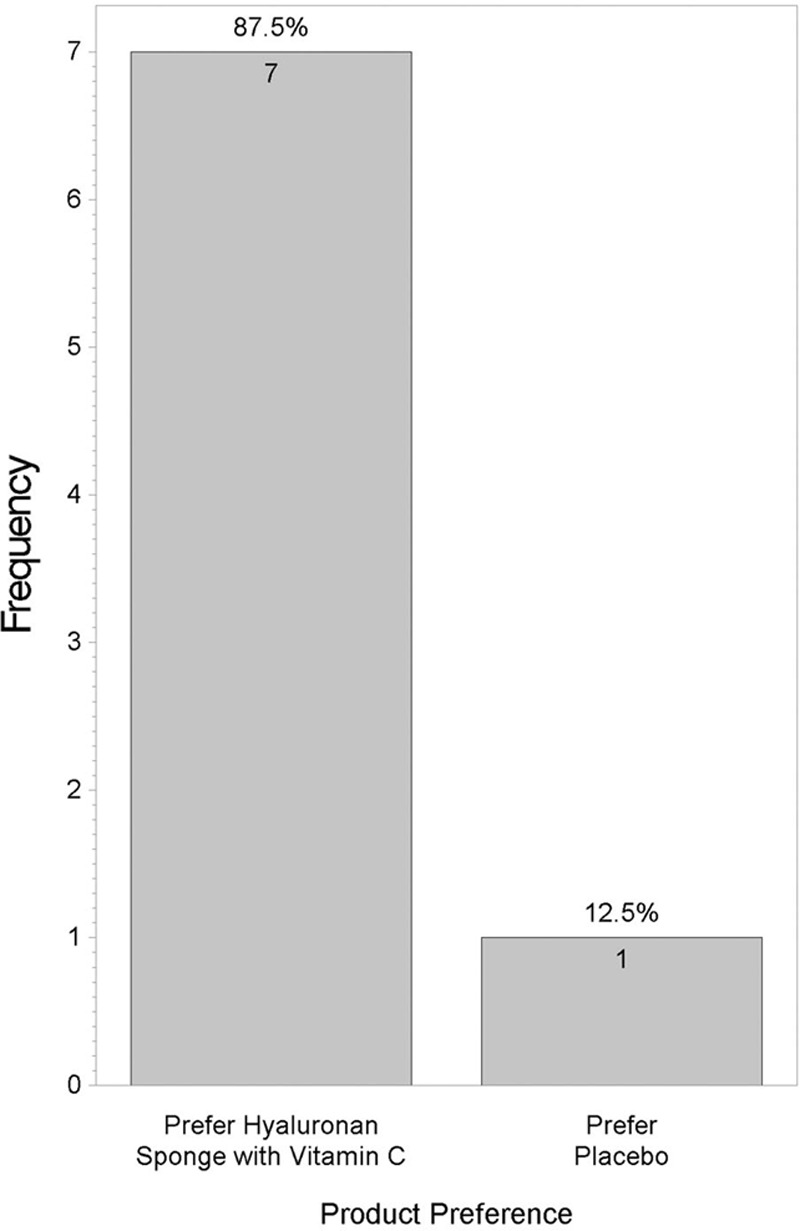

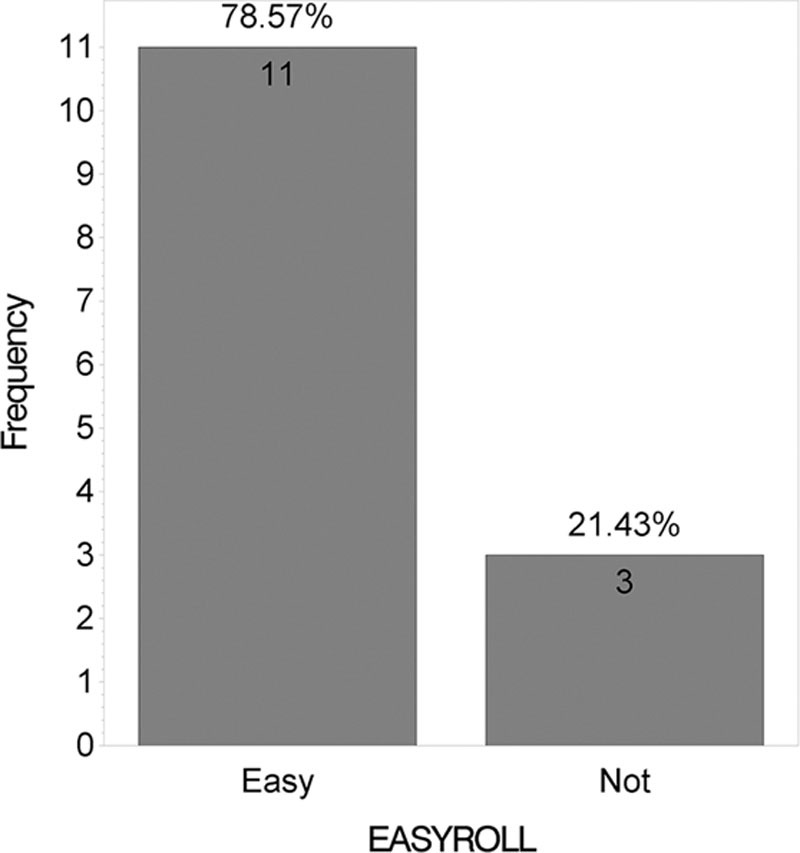

Figure 5 shows that no statistically significant difference was found between the 2 products when answers for the “Satisfied with scar” question were grouped into “very satisfied,” “satisfied,” “neutral,” and “unsatisfied” (P = 0.46). However, when “very satisfied” and “satisfied” answers were grouped and compared with “neutral” and “unsatisfied” answers, a statistically significant difference was found (P = 0.001; Figure 6). Figure 7 shows that majority of patients would buy the HA sponge with vitamin C. Figure 8 shows the micro-roller given to participants for applying the HA sponge with vitamin C after the first 12 weeks. Figure 9 shows that the majority of participants believed that the micro-roller was easy to use.

Fig. 5.

How satisfied are you with the scar line?

Fig. 6.

How satisfied are you with the scar line?

Fig. 7.

Comparison of product preference.

Fig. 8.

Micro-roller used to apply hyaluronan sponge with vitamin C (stainless steel 0.25 microns).

Fig. 9.

Satisfaction with micro-roller used to apply hyaluronan sponge with vitamin C.

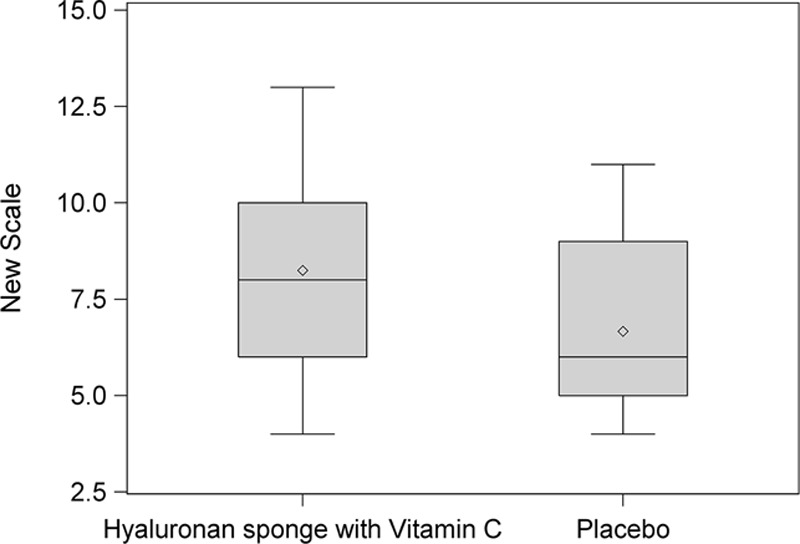

Figure 10 shows the box plot, which indicates a slightly higher mean for the side that received the HA sponge with vitamin C than for the side that received placebo.

Fig. 10.

New Scale Analysis. This box plot compares the mean (diamond) and the median (horizontal line in the box) scores.

Figure 11 shows evolution of a scar receiving HA sponge with vitamin C over the 12-week study period. The scar is thinner and more faded than the scar receiving placebo. Figures 12 and 13 show thinning of the scar over the 4- to 12-month application period.

Fig. 11.

Evolution of a scar over the 12-week study period with the use of hyaluronan sponge with vitamin C vs placebo.

Fig. 12.

Bilateral breast reduction scar at 4 months with the use of hyaluronan sponge with vitamin C vs placebo.

Fig. 13.

Bilateral breast reduction scar at 12 months with the use of hyaluronan sponge with vitamin C vs placebo.

DISCUSSION

Scarring can have a substantial psychological and financial impact on patients.2 Many noninvasive and invasive scar management options are available. Noninvasive options include compression therapy (eg, pressure garments with or without gel sheeting); static and dynamic splints; acrylic casts; masks and clips; oils, lotions, and creams; antihistamine drugs; hydrotherapy; and psychosocial counseling and advice.3,24–27 Silicon sheeting, with or without adhesive, has become a popular option for scar management.9 Massage therapy is often recommended but lacks evidence of benefit.28 Without proper trials, however, benefits are difficult to quantify objectively, although even a placebo benefit may be appreciated by patients. Invasive treatments include surgical excision and resuturing. Intralesional corticosteroid injection is widely used but is prone to complications (eg, fat atrophy, dermal thinning, pigment changes). Other treatments that have been advocated with variable outcomes include injections of fluorouracil, interferon gamma, bleomycin, radiotherapy, laser therapy, and cryosurgery.24,29–31

Hydration, 1 of 3 main areas of scar control (the others being scar support and accelerated scar maturation), reduces water loss and restores homeostasis to the scar, thereby reducing capillary hyperemia, collagen deposition, and hypertrophic scar.32 The HA sponge plays a role in maintaining hydration near the scar. The HA sponge is also different from all other forms of HA available today because of its content design and hydrating properties. Because of the water-retaining capacity of HA sponge, it facilitates the transport of metabolites and preserves tissue hydration, especially in the dermal layer. Hyaluronan likely plays a multifaceted role in the mediation of cellular and matrix events during wound healing. In addition, the larger and smaller molecules of HA penetrate the scar and contribute to accelerated wound healing, simulating fetal scarless healing by increasing the amount of HA in the area of the scar.10,12,14,33–38

In another prospective study (unpublished data, Monali Mahedia, Nilay Shah, Bardia Amirlak, 2015), we evaluated the HA sponge with zinc and found benefit with wound healing and obtaining a better scar when therapy was initiated immediately after surgical procedures. To our knowledge, this study is the first randomized controlled prospective trial showing significant patient satisfaction by using HA sponge with vitamin C in more mature scars. We also showed the ease of use of the micro-roller in this study. The micro-roller is safe and painless and activates microcirculation by stimulating the skin with microneedles on the rotating head. It has 192 surgical steel microneedles, which create microchannels that allow the ingredients to better penetrate the skin surface and acts in synergy with HA sponge with vitamin C. These channels remain open for 1 to 2 hours, and skin is able to absorb products more efficiently.39–41

Campos et al42 found photoprotective, hydration, and viscoelastic effects of a cosmetic formulation containing a dispersion of liposome with MAP, alpha-lipoic acid, and kinetin in their in vitro and in vivo experiment on hairless mouse skin and human volunteer forearm skin. After 4 weeks of application on human volunteer forearm skin, stratum corneum skin moisture and hydration of deeper layers of skin were enhanced. They concluded that the formulation can have potential antiaging effects. Before that, they had shown that MAP can cause alteration in the viscoelastic:elastic ratio, suggesting that MAP can affect the deeper layers of the skin. Vitamin C is important for the normal cutaneous metabolism and preventing early aging.42 The formulation of the HA sponge allows delivery of MAP and similar products to maturing scars.10

No adverse reactions were reported in our study, consistent with previous findings supporting the safety of ascorbic acid. In safety studies in animal models, the use of ascorbic acid on damaged skin was not associated with any adverse effects. In addition, repeat-insult patch test findings using 5% ascorbic acid were negative, supporting the finding that this group of ingredients does not present a risk of skin sensitization.

Although differences were noted in the VAS analysis due to limited number of patients, the statistical significance was not achieved. These preliminary data can lay the groundwork to larger prospective multicenter trials. However, even with these limited data, our patient satisfaction results were statistically significant and strong enough to support the routine use of this product. Another limitation of the study is the use of a VAS. Although this type of scale has been validated and is commonly used when assessing scars, it is subjective, which is the limitation in all scar assessment studies.

The method of randomization also deserves further clarification as it can be confusing to the reader why this method of randomization was used for this study. It was done to balance internal randomization and to further blind the reviewers to the potential bias. It made statistical analysis more difficult but did not affect the results overall. Two groups were internally balanced because of method of randomization.

CONCLUSIONS

The HA sponge with vitamin C is safe to use in all types of scars older than 4 weeks. It was found to have high patient satisfaction after unilateral or bilateral surgery. Overall, patients also reported that the micro-roller used to apply the product was easy to use to potentially increase the spread of the medication in older scars.

Footnotes

Disclosure: This work was supported by the Sponsor Hylaco LLC/eraclea skincare. The Article Processing Charge was paid for by Hylaco LLC/eraclea skincare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayat A, McGrouther DA, Ferguson MW. Skin scarring. BMJ. 2003;326:88–92. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7380.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:763–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walmsley GG, Maan ZN, Wong VW, et al. Scarless wound healing: chasing the holy grail. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:907–917. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schilling JA. Wound healing. Surg Clin North Am. 1976;56:859–874. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)40983-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrico TJ, Mehrhof AI, Jr, Cohen IK. Biology of wound healing. Surg Clin North Am. 1984;64:721–733. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)43388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardy MA. The biology of scar formation. Phys Ther. 1989;69:1014–1024. doi: 10.1093/ptj/69.12.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dreifke MB, Jayasuriya AA, Jayasuriya AC. Current wound healing procedures and potential care. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2015;48:651–662. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2014.12.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Giorgi V, Sestini S, Mannone F, et al. The use of silicone gel in the treatment of fresh surgical scars: a randomized study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:688–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.03096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mustoe TA. Evolution of silicone therapy and mechanism of action in scar management. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32:82–92. doi: 10.1007/s00266-007-9030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bullard KM, Longaker MT, Lorenz HP. Fetal wound healing: current biology. World J Surg. 2003;27:54–61. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6737-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neuman MG, Nanau RM, Oruña-Sanchez L, et al. Hyaluronic acid and wound healing. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;18:53–60. doi: 10.18433/j3k89d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rydell N. Decreased granulation tissue reaction after installment of hyaluronic acid. Acta Orthop Scand. 1970;41:307–311. doi: 10.3109/17453677008991516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damodarasamy M, Johnson RS, Bentov I, et al. Hyaluronan enhances wound repair and increases collagen III in aged dermal wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22:521–526. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin P. Wound healing–aiming for perfect skin regeneration. Science. 1997;276:75–81. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longaker MT, Whitby DJ, Adzick NS, et al. Studies in fetal wound healing, VI. Second and early third trimester fetal wounds demonstrate rapid collagen deposition without scar formation. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:63–68. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(05)80165-4. discussion 8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Namazi MR, Fallahzadeh MK, Schwartz RA. Strategies for prevention of scars: what can we learn from fetal skin? Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:85–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The HylaSponge System. Hylaco Website. Available at: http://www.hylaco.com/index.html. Accessed July 15, 2015.

- 18.Segall AI, Moyano MA. Stability of vitamin C derivatives in topical formulations containing lipoic acid, vitamins A and E. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2008;30:453–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2494.2008.00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kameyama K, Sakai C, Kondoh S, et al. Inhibitory effect of magnesium L-ascorbyl-2-phosphate (VC-PMG) on melanogenesis in vitro and in vivo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:29–33. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90830-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campos PM, Gonçalves GM, Gaspar LR. In vitro antioxidant activity and in vivo efficacy of topical formulations containing vitamin C and its derivatives studied by non-invasive methods. Skin Res Technol. 2008;14:376–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2008.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elmore AR. Final report of the safety assessment of L-ascorbic acid, calcium ascorbate, magnesium ascorbate, magnesium ascorbyl phosphate, sodium ascorbate, and sodium ascorbyl phosphate as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol. 2005;24(Suppl 2):51–111. doi: 10.1080/10915810590953851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moores J. Vitamin C: a wound healing perspective. Br J Community Nurs. 2013;Suppl:S6, S8–S6, 11. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2013.18.sup12.s6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva GM, Maia Campos PM. Histopathological, morphometric and stereological studies of ascorbic acid and magnesium ascorbyl phosphate in a skin care formulation. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2000;22:169–179. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-2494.2000.00017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Widgerow AD, Chait LA, Stals PJ, et al. Multimodality scar management program. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33:533–543. doi: 10.1007/s00266-008-9276-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharp PA, Pan B, Yakuboff KP, et al. Development of a best evidence statement for the use of pressure therapy for management of hypertrophic scarring. J Burn Care Res. 2015 May 28. [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirshowitz B, Lindenbaum E, Har-Shai Y, et al. Static-electric field induction by a silicone cushion for the treatment of hypertrophic and keloid scars. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:1173–1183. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199804050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorfmüller M. [Psychological management and after-care of severely burned patients]. Unfallchirurg. 1995;98:213–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin TM, Bordeaux JS. The role of massage in scar management: a literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:414–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boateng JS, Matthews KH, Stevens HN, et al. Wound healing dressings and drug delivery systems: a review. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97:2892–2923. doi: 10.1002/jps.21210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haider AS, Grabarek J, Eng B, et al. In vitro model of “wound healing” analyzed by laser scanning cytometry: accelerated healing of epithelial cell monolayers in the presence of hyaluronate. Cytometry A. 2003;53:1–8. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.10032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meaume S, Le Pillouer-Prost A, Richert B, et al. Management of scars: updated practical guidelines and use of silicones. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:435–443. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2014.2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King SR, Hickerson WL, Proctor KG. Beneficial actions of exogenous hyaluronic acid on wound healing. Surgery. 1991;109:76–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghersetich I, Lotti T, Campanile G, et al. Hyaluronic acid in cutaneous intrinsic aging. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:119–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1994.tb01540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abatangelo G, Martelli M, Vecchia P. Healing of hyaluronic acid-enriched wounds: histological observations. J Surg Res. 1983;35:410–416. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(83)90030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aya KL, Stern R. Hyaluronan in wound healing: rediscovering a major player. Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22:579–593. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iocono JA, Ehrlich HP, Keefer KA, et al. Hyaluronan induces scarless repair in mouse limb organ culture. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:564–567. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laurent TC, Fraser JR. Hyaluronan. FASEB J. 1992;6:2397–2404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weindl G, Schaller M, Schäfer-Korting M, et al. Hyaluronic acid in the treatment and prevention of skin diseases: molecular biological, pharmaceutical and clinical aspects. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;17:207–213. doi: 10.1159/000080213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doddaballapur S. Microneedling with dermaroller. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009;2:110–111. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.58529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwarz M, Laaff H. A prospective controlled assessment of microneedling with the Dermaroller device. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:146e–148e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182131e0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liebl H, Kloth LC. Skin cell proliferation stimulated by microneedles. J Am Coll Clin Wound Spec. 2012;4:2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jccw.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campos PM, de Camargo Júnior FB, de Andrade JP, et al. Efficacy of cosmetic formulations containing dispersion of liposome with magnesium ascorbyl phosphate, alpha-lipoic acid and kinetin. Photochem Photobiol. 2012;88:748–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2012.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]