Abstract

Objective

To analyse the process of implementing and enforcing smoke-free environments, tobacco advertising, tobacco taxes and health warning labels from Costa Rica's 2012 tobacco control law.

Method

Review of tobacco control legislation, newspaper articles and interviewing key informants.

Results

Despite overcoming decades of tobacco industry dominance to win enactment of a strong tobacco control law in March 2012 consistent with WHO's Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, the tobacco industry and their allies lobbied executive branch authorities for exemptions in smoke-free environments to create public confusion, and continued to report in the media that increasing cigarette taxes led to a rise in illicit trade. In response, tobacco control advocates, with technical support from international health groups, helped strengthen tobacco advertising regulations by prohibiting advertising at the point-of-sale (POS) and banning corporate social responsibility campaigns. The Health Ministry used increased tobacco taxes earmarked for tobacco control to help effectively promote and enforce the law, resulting in high compliance for smoke-free environments, advertising restrictions and health warning label (HWL) regulations. Despite this success, government trade concerns allowed, as of December 2015, POS tobacco advertising, and delayed the release of HWL regulations for 15 months.

Conclusions

The implementation phase continues to be a site of intensive tobacco industry political activity in low and middle-income countries. International support and earmarked tobacco taxes provide important technical and financial assistance to implement tobacco control policies, but more legal expertise is needed to overcome government trade concerns and avoid unnecessary delays in implementation.

INTRODUCTION

WHO's Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) has accelerated the enactment of tobacco control laws globally.1–3 Efforts by the tobacco industry to block and undermine tobacco control laws after they pass have been well documented in high-income countries (HICs), including lobbying tobacco marketing regulations,4 influencing tobacco taxes,5 and exaggerating illicit trade in tobacco.6 Efforts by civil society to ensure strong implementation of tobacco control policies have also been well documented in HICs.7,8

However, such efforts have been less studied in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). This is surprising given that important legal and political battles have occurred in LMICs during the implementation phase, especially in Latin America,9–11 including Philip Morris International's (PMI) effort to overturn strong cigarette package health warning labels in Uruguay12 and constitutional challenges to Guatemala's13 and Mexico's14 smoke-free laws, and Colombia's and Panama's tobacco advertising bans.15,16

In Costa Rica, PMI and British American Tobacco (BAT) blocked tobacco control legislation for decades,17 but between 2010 and 2012 the health advocacy network, Red Nacional Antitabaco (RENATA, National Anti-Tobacco Network), convinced legislators to enact legislation implementing the FCTC18 Law 9028 in March 2012.19 Law 9028 established 100% smoke-free environments in workplaces and public places, prohibited tobacco advertising, sponsorship and promotion (except in places and events that only permit adult access, and through direct communication with vendors and consumers), increased tobacco taxes and penalties for non-compliance, and required pictorial health warning labels (HWL) covering 50% of the front and back of the package. Despite securing a comprehensive tobacco control law, the implementation phase of the policymaking process continues to be a site of tobacco industry political activity.

This paper highlights commonalities between industry political activity in high and middle income countries (particularly with respect to tobacco industry lobbying during the implementation phase), and underlines the importance of civil society support in ensuring strong implementation of the FCTC.

METHODS

We reviewed Costa Rican tobacco control legislation (available at http://www.asamblea.go.cr/Legislacion/default.aspx) and available online Costa Rican newspaper articles from La Nación (http://www.nacion.com) and Crhoy (http://www.crhoy.com) and news articles from Google (http://www.google.com). We used standard snowball searches20,21 beginning with search terms in English and Spanish `tobacco law', `ley anti-tabaco', `tobacco taxes', `impuestos del tabaco', `regulation', `reglamento', `smoke-free', `espacios libres de humo', `tobacco advertising', `publicidad de tabaco', `health warnings', `advertencias sanitarias', and legislation numbers. We also interviewed 11 Costa Rican tobacco control advocates, lawyers and policymakers who were closely involved in the process. Interviews were conducted in Spanish and then transcribed into English in accordance with a protocol approved by the UCSF Committee on Human Research. Through the interviews, we also obtained letters from international health organisations, the Health Ministry, and the Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Commerce pertaining to the regulations. Results from these sources were triangulated.

RESULTS

Establishing regulations to implement Law 9028

Following enactment of Law 9028 in March 2012 (table 1), the Ministries of Health, of Economy, Industry and Commerce, and of Labor and Social Security, and Office of the Presidency, began a 90-day period to develop the `reglamento' (regulations) to enforce Law 9028.22 Between March and June 2012, the Health Ministry held public consultations to receive suggestions for specifically how the law should be implemented and enforced.

Table 1.

Tobacco industry and health advocacy activity during implementation of Law 9028 (2012–2015)

| Issue | Law 902819 | Regulations22 | Tobacco industry (and front groups) interference | Health advocate responses | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoke-free environments | 100% smoke-free, except in hotels | 100% smoke-free, except in hotels and in work places `to allow smoking in outdoor spaces located 5 m from the “productive unit'” | ▶ Lobbied Health Ministry, complaining about smokers' rights to smoke in open areas (April–June 2012)25 | ▶ Did not pursue legal action due to legal costs and high compliance with law.27 | ▶ Health Ministry allowed exception due to smoker complaints (June 2012)25,29 |

| ▶ Electronic cigarettes not defined | ▶ Electronic cigarettes prohibited in smoke-free environments | ▶ CACORE and CCH complained in the media that each had lost 25% of their revenues31 | ▶ Questioned the Health Ministry and complained in the media about exception for smoking in open areas28 | ▶ Despite exception, enforcement has been strong and compliance has been high | |

| ▶ 80% of a group of employers reported that they did not have economic loses (October 2012)31 | |||||

| Tobacco Advertising, Promotion and Sponsorship (TAPS) | ▶ 100% prohibited, except places and events that only permit adult access and through direct communication with vendors and consumers | ▶ 100% prohibited, except places and events that only permit adult access and through direct communication with vendors and consumers | ▶ Lobbied the Health Ministry, MEIC, and the office of the presidency, complaining that TAPs violate intellectual property rights, the right of free enterprise, freedom of expression and consumer rights to information.30 | ▶ Lobbied Health Ministry to clarify and expand regulations to include banning TAPs through CSR and at the POS (May 2012)23,24 | ▶ Enforcement has been strong and compliance has been high, except TAPS at the POS |

| ▶ TAPS not defined at the POS | ▶ CSR campaigns prohibited | ▶ Issued pamphlets to merchants, endorsed by CACORE that argued the regulation permitted TAPS at the POS44,45 | ▶ Presented Health Ministry with letters about TAPS at the POS and compliance with Article 13 (September 2013)41 | ▶ Health Minister Corrales issued a directive permitting TAPS at the POS to respect the consumer's right to information42 | |

| ▶ Electronic digital advertising prohibited | ▶ Filed complaints with Health Ministry about tobacco companies promoting to merchants that the regulation permitted TAPS at the POS44,45 | ||||

| ▶ TAPS 100% prohibited at the POS | |||||

| Tobacco Taxes | ▶ 20 colones (US$0.04) per cigarette package | ▶ Same | ▶ Complained and exaggerated in the media that the tobacco tax increase was directly related to the upsurge in smuggled cigarettes49 | ▶ Tobacco taxes helped expand tobacco control programmes, support implementation, and increase global participation in international tobacco control efforts28,36,37 | ▶ Finance Ministry and fiscal control police reported that Law 9028 had little to no impact on smuggled cigarettes48 |

| ▶ 100% of funds allocated to CCSS (60%), Health Ministry (20%), IAFA (10%), and ICODER (10%) | |||||

| Cigarette Package Health Warning Labels (HWLs) | ▶ Front: 50% pictorial. | ▶ Same | ▶ Lobbied MEIC, complaining the HWLs were a technical barrier to trade and that it was necessary to consult trade agreements (eg, WTO) before adopting HWL regulations25 | ▶ Presented Health Ministry with legal advice that the WTO Preamble recognises government rights to take necessary measures to protect public health and that more than 50 countries have established 50% pictorial HWLs following FCTC Article 11 (April 2013)52,58* | ▶ Regulations implemented in September 2014 instead of June 201360 |

| ▶ Back: 50% pictorial | ▶ Lobbied Health Ministry for a 2-month extension to implement new designs37 | ▶ Health Ministry allowed a 2-month grace period for new pictorial HWLs to be implemented61 |

As of September 2014, more than 60 countries have established 50% pictorial HWLs.

CACORE, Costa Rican Chamber of Restaurants; CCH, Costa Rican Chamber of Hotels; CCSS, Costa Rican Social Security Fund; CSR, Corporate Social Responsibility; FCTC, Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; IAFA, Institute of Alcoholism and Drug Dependence; ICODER, Costa Rican Institute of Sport and Recreation; MEIC, Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Commerce; POS, Point of Sale; WTO, World Trade Organization.

RENATA closely followed the consultation process and worked with the US-based Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids (TFK), Corporate Accountability International (CAI) and O'Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University, the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, and the Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO, WHO's regional office for Latin America), to submit comments on the proposed regulations. PAHO, TFK and CAI also submitted additional comments.23,24 These comments included recommendations to prohibit the usage of electronic cigarettes in smoke-free public places, clearer timetables for HWLs, the total prohibition of tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship (TAPS) at the point-of-sale (POS) and a ban on electronic and digital advertising and corporate social responsibility (CSR) campaigns.

The tobacco companies submitted arguments predicting increased illicit trade, compromised freedom and negative employment and economic effects as a consequence of smoke-free environments, tobacco advertising limitations, tobacco tax increases and HWLs. In particular, tobacco companies requested longer provisional periods for implementation.25 Tobacco companies also objected to prohibiting smoking in open spaces citing smokers' rights; 700 smokers also made the same complaint,26 which health officials recognised as a much larger consultation response from the public than normally received.25,27

Through formal submissions during the consultation period, RENATA, with the assistance of international health groups, succeeded in convincing the Health Ministry to prohibit the use of electronic cigarettes in workplaces, restaurants, bars and bus stops, POS, electronic and digital tobacco advertising, and CSR campaigns in the final regulation to implement Law 9028, which was published in June 2012. However, the regulation allowed an exception for smoking in open areas in workplaces. While the regulation addressed the enforcement of smoke-free environments, tobacco advertising and cigarette taxes, HWL regulations were not issued.

Smoke-free environments

Law 9028 required smoking to be completely prohibited including in workplaces, restaurants, bars and bus stops (table 1).

The law did not mention outdoor areas, leaving it up to the government to decide how to handle them through the regulatory process; the implementing regulation allowed `smoking in outdoor spaces' in workplaces, reflecting the tobacco industry's and 700 smokers' complaints submitted during the public comment period. RENATA sent letters to the Health Ministry questioning this exemption.27,28 Health Minister Daisy Corrales responded by saying the Ministry made the change because of the submission by the 700 smokers and the fear of a constitutional challenge based on individual rights,25,29 despite the Constitutional Court ruling in March 2012 that confirmed the legality of 100% smoke-free law.

Several public health advocates and officials believe that someone in the president's office altered the regulation at the last minute to add this exception.27,28,30 Members of RENATA felt the regulation could be challenged legally but decided it was not worth the legal costs to challenge this exemption since compliance with the law was high, and that this exception did not create confusion among the public.27,28

As everywhere, the Health Ministry also received complaints from the Cámara Costarricense de Restaurantes y Afines (CACORE, Costa Rican Chamber of Restaurants) and the Cámara Costarricense de Hoteles (CCH, Costa Rican Chamber of Hotels), long-time tobacco industry front group used to oppose smoke-free legislation,17 who complained that after 1 year they had each lost 25% of their revenues.31 These complaints occurred despite an October 2012 study done by the research firm, the Expo para Hoteles y Restaurantes (Exphore, Expo for Hotels and Restaurants) that found that 80% of a group of employers reported no revenue losses.32

The Health Ministry's enforcement of smoke-free environments has been effective. By March 2014, the Health Ministry had made over 70 000 inspections, collected nearly ¢33 million (US$66 000) from over 500 fines, and reported a 95% compliance rate.33 The Health Ministry made repeated visits to ensure compliance, including surprise visits to several restaurants and bars in the evenings.34 The public health advocates stated that compliance and respect for the law has been very high due to increased awareness and publicity of Law 9028.25,28,35–39

Tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship

Health advocates interviewed for this study reported that the Health Ministry's enforcement of TAPS has also been effective except for two complaints filed against BAT that the Health Ministry withdrew due to insufficient evidence to suggest a violation.40

Health advocates also reported that compliance with TAPS has been high, except at the POS. Although the regulation banned TAPS at the POS, vendors continued to display cigarette packages at the POS. In response, RENATA complained to the Health Ministry that this was a clear violation of the regulation.27,28,36 On 26 September 2013, Health Ministry lawyers sent a letter to Health Minister Corrales stating that the cigarette price list was displayed with large letters, colours, and special marking font alluding to certain brands, which was an advertisement and promotion and a clear violation of the law.41 Members of the Health Ministry interviewed for this study reported that tobacco companies lobbied the president's office to pressure Health Minister Corrales to issue a directive allowing TAPS at the POS. These officials stated that tobacco companies argued that prohibiting POS advertising would violate trade agreements that protected intellectual property rights and consumer rights to information.27,30 On 1 October 2013, Health Minister Corrales issued a directive that stated displaying cigarette packages at the POS was not a form of advertising, and that the Ministry needed to respect the consumer's right to information.42

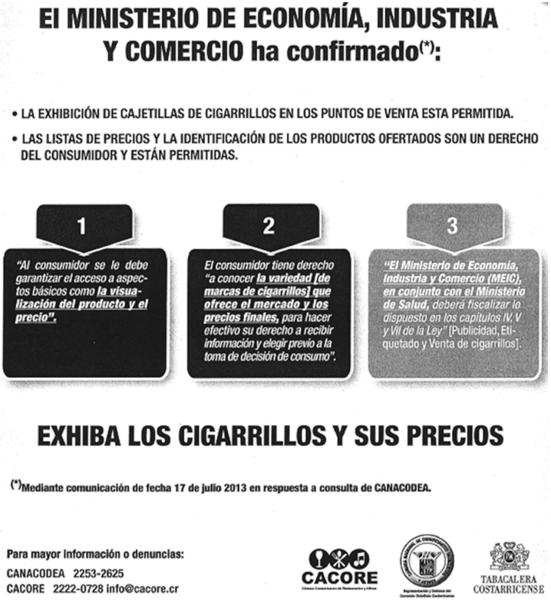

When President Luis Guillermo Solís took power in May 2014, RENATA worked to reverse this decision regarding POS advertising. RENATA again requested assistance from international health groups and on 28 May 2014, these groups sent a letter to new health minister María Elena Lopez restating that allowing advertising at POS was a clear violation of the law, and that former health minister Corrales's directive was an error in application and interpretation.43 In November 201444 and January 2015,45 RENATA wrote to the Health Ministry complaining that BAT and PMI were issuing pamphlets to merchants promoting the error in application. The pamphlets, endorsed by long-time industry ally and hospitality front group CACORE, stated that the Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Comercio (MEIC, Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Commerce) con-firmed that the regulation permitted the display of cigarette packages at the POS, and that listing cigarette prices was the consumer's right to information (figure 1). RENATA has continually requested Health Minister Lopez to correct this error, but as of December 2015, TAPS at the POS remained permitted.

Figure 1.

Throughout 2014 and 2015, BAT and PMI issued pamphlets, endorsed by hospitality front group CACORE, to merchants to claim that TAPS at POS remained permitted. The pamphlet states, `the Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Commerce has confirmed: The display of cigarette packages at the point of sale is permitted, and the price lists and the identification of the products offered are a right of the customer and permitted' (translated by author).

Tobacco taxes

Law 9028 raised the tax on cigarettes from ¢5 (US$.01) to ¢20 (US$.04) per pack,46 and distributed the tax funds among government agencies to address the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of tobacco-related diseases. Health advocates and officials interviewed for this study all emphasised the importance of these funds in expanding tobacco control programmes, supporting the implementation of Law 9028, and increasing regional and global participation in international tobacco control efforts.

The funds were allocated to four governmental health agencies: the Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social (CCSS, Costa Rican Social Security Fund, 60%), the Health Ministry (20%), the Instituto sobre Alcoholismo y Framacodependencia (IAFA, Institute of Alcoholism and Drug Dependence, 10%), and the Instituto Costarricense del Deporte y la Recreación (ICODER, Costa Rican Institute of Sport and Recreation, 10%). The CCSS and IAFA, which both work on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of tobacco-related diseases, have used the funds to finance prevention programmes, treatment clinics and research. The Health Ministry and ICODER, placed print and broadcast advertisements directed at teenagers and young adults illustrating the importance of living a healthy smoke-free life using prominent and youth-appealing musicians and sports athletes.

The expanded funds also allowed the Health Ministry to send a delegation for the first time to the FCTC Conference of the Parties' (COP) sixth session in Moscow, Russian Federation, in October, 2014. (The COP develops implementation guidelines and protocols for the FCTC and monitors implementation). The Costa Rican delegates participated in work group sessions on the application of FCTC Articles 9 and 10 (Regulating and Disclosing Tobacco Product Emissions) and 19 (Liability and Legislative Action), and specifically shared the importance of tobacco taxes established in Law 9028, and coordinated a session on electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS). Costa Rica submitted a draft decision that encouraged the COP to consider measures proposed by the WHO to regulate or even prohibit ENDS. The draft decision generated additional discussion at the COP leading to a decision that invited the parties to consider regulating or prohibiting ENDS as medicinal products, consumer products or other categories, taking into account health protection.47 The COP also urged the parties to consider restricting or banning the advertisement, publicity and sponsorship of ENDS, and called for the scientific and regulatory evidence of ENDS to be presented at the next COP session in 2016.37

In March 2014, 2 years after the tax increase took effect, the Finance Ministry reported that Law 9028 had little to no impact on smuggled cigarettes,48 despite continued tobacco industry claims in the media that raising taxes increased contraband and smuggled cigarettes.49 For example, in November 2013, PMI complained cigarette seizures increased five times more than in 2012 (2.3 million to 12.3 million),49 but the Finance Ministry reported that the increase was due to improved enforcement after the Ministry strengthened the Fiscal Control Police with additional staff, and an increased focus on organisations that import illegal cigarettes and their distribution networks.48

Cigarette package health warning labels

While the regulation for smoke-free environments, tobacco advertising and tobacco taxes of Law 9028 was issued in June 2012, the regulation for HWLs was not issued until July 2013, and not enforced until September 2014 due to international trade concerns. RENATA, which submitted comments for HWLs during the consultation period, complained in the media and questioned the Health Ministry as to why HWLs were not included in the regulation36; the Health Ministry responded that it wanted to keep HWLs separate to ensure compliance with Costa Rica's international obligations. According to Health Minister Corrales, during the public consultation, the president's office and the Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Commerce (MEIC), who continuously defended the positions of tobacco companies,50 argued that HWLs would violate trade agreements, particularly technical barriers to trade. On 11 September 2012, MEIC sent a letter to the Health Ministry requesting that HWLs needed to correspond with technical regulations that included a notification with the World Trade Organization's (WTO) Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) Agreement.51 According to the letter by MEIC, the notification process in the TBT can assist in avoiding unnecessary obstacles to international trade.

In response, Costa Rican health advocates requested legal assistance from international health groups. On 24 October 2012, TFK and the O'Neill Institute sent a legal opinion to the Health Ministry stating that at the time more than 40 jurisdictions (countries) had implemented pictorial HWLs covering 50% of the package following FCTC Article 11 guidelines, HWLs were a necessary measure to protect public health and that pictorial HWLs did not constitute a technical barrier to trade.52 The Health Ministry reiterated these arguments in its formal response to MEIC.53 Even though 40 other countries had adopted similar policies, MEIC continued to argue that it would make inquiries to WTO's TBT to avoid confrontation with technical regulations.54

In April 2013, again working in close collaboration with international health groups, RENATA generated media coverage to expose the president's office and MEIC's unwillingness to publish the HWL regulations. RENATA held a press conference at the Legislative Assembly to pressure the president to approve the not-yet-released HWL regulations,55 which included placing large lifesize examples of potential pictorial HWLs in front of the Legislative Assembly56,57 (figure 2). The press conference also included speeches by international health experts and a letter from international health groups to President Chinchilla requesting that HWLs be released as HWLs would unlikely trigger another country to file a complaint with WTO against Costa Rica's HWLs.58

Figure 2.

In April 2013, RENATA held a press conference at the Legislative Assembly to pressure the president to approve the not-yet-released HWL regulations, which included placing large lifesize examples of potential pictorial HWLs in front of the Legislative Assembly.55

President Chinchilla finally signed the HWL regulation on 9 July 2013,59 requiring tobacco companies within 1 year to include pictorial HWLs that cover 50% of the front and back of cigarette packages as Law 9028 required.60

Although HWLs finally came into effect on 18 September 2014, the Health Ministry allowed an additional 2-month grace period for establishments to sell both old textual warnings and newly adopted pictorial HWLs due to retailer complaints about economic losses.61

Health advocates interviewed for this study in November 2014 reported that compliance with the law was high.27,28,30,36,37

DISCUSSION

Despite overcoming decades of tobacco industry dominance to win enactment of Law 9028 in March 2012, the implementation phase continued to be a site of intensive tobacco industry political activity.62

Similar to other HICs,63–66 and LMICs,67,68 tobacco companies attempted to weaken already approved smoke-free policies by lobbying for exemptions in smoke-free areas during the writing of implementing regulations. The submission of similar public comments to exempt outdoor smoke-free areas by 700 smokers represented a much larger response to a public consultation than normal is a common industry tactic used elsewhere.69–72 Although the industry succeeded in lobbying for an exemption for outdoor areas in Costa Rica, similar to exemptions for hotel rooms, smoking cubicles, smoking clubs, and tobacco stores that have been included in the regulations of smoke-free policies in other countries,67,73,74 advocates mentioned this minor exception did not affect the strong compliance with the law.

Similar to other countries,66,75–80 tobacco company front groups in the hospitality sector claimed that Law 9028 hurt their business revenues. These efforts were unsuccessful in Costa Rica because they did not create confusion among the public, and a study in Costa Rica done by the research firm, Exphore, consistent with evidence globally,76–78 illustrated that smoke-free laws have no effect or a positive effect on hospitality business revenues. As in other countries,81–84 tobacco companies claimed that the increase in cigarette taxes led to a significant rise in contraband, but 2 years after the tax increase took effect, the Finance Ministry reported that Law 9028 had little to no impact on smuggled cigarettes.

Tobacco companies and their allies in government were also able to use trade concerns over tobacco to successfully help prevent, as of December 2015, the implementation of TAPS at the POS, and delay HWLs for 15 months. As in other countries,85,86 the Costa Rican government claimed that the TAPS ban at the POS violated freedom of expression, the right to free enterprise and intellectual property rights, despite constitutional courts that have ruled in favour of public health protection.86–88 Furthermore, international courts, such as the European Free Trade Association Court have ruled governments could legally ban tobacco products at POS.85

The Costa Rican Government also claimed that pictorial HWLs violated technical barriers to trade despite 50 other countries ignoring these claims, and constitutional court decisions rejecting trade claims in favour of rights to life and health.89–91 Typically, government trade concerns over tobacco have occurred over the most progressive HWLs globally,92 as a key tobacco industry strategy is to block a global diffusion of best practices.93 The Costa Rica experience illustrates how government trade concerns can delay modest HWL advances.

These trade concerns over tobacco control policies signify the growing need for legal expertise on issues related to international trade and investment law, especially in LMICs, which often lack sufficient resources and tend to be more sensitive to trade relations. In response to this growing concern, on 18 March 2015, Michael Bloomberg and Bill Gates announced the launching of an `anti-tobacco trade litigation fund,' a US$4 million fund that will assist countries in drafting legislation `to avoid legal challenges and potential trade disputes'.94 Health groups and organisations should also develop stronger relationships with trade ministries and the executive branch, and encourage health ministries to educate them on the importance of the FCTC.

While industry pressure on the writing of implementing regulations can weaken the effect of a law, the implementing regulations also provide an important opportunity for tobacco control organisations to clarify and expand the definitions of particular aspects of the law. RENATA, with the assistance of international health groups, submitted formal comments and succeeded in convincing the Health Ministry to expand advertising restrictions by banning CSR programmes, which violate FCTC Article 5.3 (tobacco industry interference) by effectively promoting tobacco companies as socially responsible companies.95 Thus, banning CSR aims to deny industry access to influence policymakers96 to endorse weaker regulations as reasonable alternatives to effective tobacco control policies. This strategy has been used in high97–99 and lower and middle income68,100,101 countries to avoid stricter regulations on smoking in public places,10,14,17,102 tobacco advertising,9,17,102,103 health warning labels17,104 and tobacco farming and labour practices.105–107

The earmarked tobacco taxes for tobacco control programmes provided much needed financial assistance to combat industry opposition and effectively promote, monitor, enforce and create awareness about smoke-free environments and TAPS restrictions. The Health Ministry consistently made inspections at restaurants and bars even at night time to enforce the law, which are important challenges in LMICs,67,101 even in places with high-level compliance.14 As elsewhere,108–111 increased funding from tobacco taxes for these programmes also led to reductions in overall tobacco use.

Costa Rica's success in these areas can also be attributed to the growth of networking and coalition building across the Latin American and Caribbean countries since the early 2000s,112 which helped foster a more cohesive and effective tobacco control movement in Costa Rica. This movement has been strengthened and supported by international financial and technical support, most notably from the Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use, aimed at lowering tobacco consumption in LMICs.

Limitations

We were denied an interview to speak with any member or staff from the president's office, or MEIC, to discuss issues pertaining to TAPS at the POS and HWLs. Although complaints raised by MEIC are similar to concerns raised by the tobacco industry in other countries, we were not given access to tobacco industry correspondence. We were also denied an interview with any tobacco industry representative. Therefore, we could not obtain any copies of formal spoken or written trade threats that were issued by tobacco companies to the Costa Rica Government.

CONCLUSION

The implementation phase continues to be a site of intensive tobacco industry political activity. Tobacco taxes provided important financial assistance to help promote and enforce TAPS restrictions and smoke-free environments, while international technical support helped strengthen and issue the regulations. Despite this success, government trade concerns allowed the industry to block TAPS at the POS and delay HWLs. Therefore, international funders and organisations should provide legal resources to LMICs to communicate the importance of FCTC to trade ministries and properly implement all tobacco control regulations without unnecessary delays.

What this paper adds.

-

▶

In high-income countries, the tobacco industry has a history of working to block implementation of tobacco control laws after they pass, including influencing governments during the consultation period to win favourable regulations.

-

▶

Costa Rica provides an example of how aggressive action by health advocates in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), combined with technical support from international health groups and support from earmarked tobacco taxes, can overcome tobacco industry opposition and help strengthen implementing regulations.

-

▶

The implementation phase in LMICs continues to be a site of intensive tobacco industry political activity, including lobbying for exemptions in smoke-free areas, exaggerating the rise in contraband due to cigarette tax increases, and using trade concerns to delay implementation.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Teresita Arrieta, Nydia Amador, Edwin Chavarría, and the interviewees for the information provided for this study.

Funding This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Grant CA-87472. The funding agency played no role in the conduct of the research or the preparation of this article.

Footnotes

Contributors EC collected the raw data and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. PS helped revise the paper. SAG initiated and supervised the project and helped revise the paper.

Competing interests None declared.

Ethics approval This study was conducted with the approval of the UCSF Committee on Human Research.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement Most data are public documents and media reports. The interviews are available to qualified researchers on request to the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hiilamo H, Glantz SA. Implementation of effective cigarette health warning labels among low and middle income countries: state capacity, path-dependency and tobacco industry activity. Soc Sci Med. 2015;124:241–5. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanders-Jackson AN, Song AV, Hiilamo H, et al. Effect of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and voluntary industry health warning labels on passage of mandated cigarette warning labels from 1965 to 2012: transition probability and event history analyses. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:2041–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uang R, Hiilamo H, Glantz SA. Accelerated adoption of smoke-free laws after ratification of the World Health Organization framework convention on tobacco control. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:166–71. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savell E, Gilmore AB, Fooks G. How does the tobacco industry attempt to influence marketing regulations? A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e87389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith KE, Savell E, Gilmore AB. What is known about tobacco industry efforts to influence tobacco tax? A systematic review of empirical studies. Tob Control. 2013;22:144–53. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joossens L, Lugo A, La Vecchia C, et al. Illicit cigarettes and hand-rolled tobacco in 18 European countries: a cross-sectional survey. Tob Control. 2014;23(e1):e17–23. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman S, Wakefield M. Tobacco control advocacy in Australia: reflections on 30 years of progress. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28:274–89. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegel M. The effectiveness of state-level tobacco control interventions: a review of program implementation and behavioral outcomes. Annu Rev Public Health. 2002;23:45–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.092601.095916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sebrie E, Glantz SA. Attempts to undermine tobacco control: tobacco industry “youth smoking prevention” programs to undermine meaningful tobacco control in Latin America. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1357–67. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.094128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sebrie EM, Glantz SA. “Accommodating” smoke-free policies: tobacco industry's Courtesy of Choice programme in Latin America. Tob Control. 2007;16:e6. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.018275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider NK, Sebrie EM, Fernandez E. The so-called “Spanish model”—tobacco industry strategies and its impact in Europe and Latin America. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:907. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGrady B. Implications of ongoing trade and investment disputes concerning tobacco: Philip Morris v. Uruguay. In: Tania Voon AM, Liberman J, Ayres G, editors. Public Health and Plain Packaging of Cigarettes: Legal Issues. Georgetown University; Washington DC: 2012. pp. 100–120. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cabrera OA, Madrazo A. Human rights as a tool for tobacco control in Latin America. Salud Publica Mex. 2010;52(Suppl 2):S288–297. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342010000800026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crosbie E, Sebrie EM, Glantz SA. Strong advocacy led to successful implementation of smokefree Mexico City. Tob Control. 2011;20:64–72. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cabrera OA, Carballo J. Tobacco control litigation: broader impacts on health rights adjudication. J Law Med Ethics. 2013;41:147–62. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Accion de Inconstitutionalidad: Propuesta por Rodriguez Robles & Espinoza En Representation of British American Tobacco, Panama, SA Contra el Articulo Del Decreto Ejecutivo N-611 De 3 De Junio De 2010 Del Ministerio De SaludExp N-192–11. Gaceta Oficial Digital, San José; Costa Rica: Feb 2, 2014. República de Panama Organo Judicial Corte Suprema de Justicia. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crosbie E, Sebrie EM, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry success in Costa Ric: the importance of FCTC article 5.3. Salud Publica Mex. 2012;54:28–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crosbie E, Sosa P, Glantz SA. Costa Rica's Successful Implementation of the FCTC. Salud Publica Mex. 2015 doi: 10.21149/spm.v58i1.7669. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asamblea Legislativa de la República de Costa Rica . Ley General de Control del Tabaco y Sus Effectos Nocivos en la Salud N. 9028. San José; Costa Rica: Mar 26, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malone RE, Balbach E. Tobacco industry documents: treasure trove or quagmire? Tob Control. 2000;9:334–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacKenzie R, Collin J, Lee K. The tobacco industry documents: an introductory handbook and resource guide for researchers. Centre on Global Health and Change, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; London: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asamblea Legislativa de la República de Costa Rica . Reglamento a La Ley General De Control de Tabaco y Sus Efectos Nocivos en la Salud. Poder Ejecutivo; Costa RIca: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, Corporate Accountability International . Comments for the Regulation of the Law 9028, Ministerio de Salud. San José; Costa Rica: Jun 5, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanco A. Electronic interview by Eric Crosbie. University of California; Santa Cruz, California: Mar 11, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corrales D. Interview by Eric Crosbie, Ministerio de Salud. San José; Costa Rica: Nov 11, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cerdas D. La Nacion. San José; Costa Rica: Aug 14, 2012. Salud cambio reglamento por quejas de 700 fumadores. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castro R. Interview by Eric Crosbie, Ministerio de Salud. San José, Costa Rica: Nov 10, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arrieta T. Interview by Eric Crosbie, Instituto de Alcoholismo y Farmacodependencia. San José; Costa Rica: Nov 7, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cantero M. Ley faculta a patronos para prohibir del todo fumar en las empresas. La Nacion, San José; Costa Rica: Aug 18, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chavarria E. Interview by Eric Crosbie, Ministerio de Salud. San José; Costa Rica: Nov 11, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quiros LV. El Financiero. Aug 25, 2013. Ley antitabaco genera ganancias y pérdidas para restaurantes y hoteles. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quiros AB. [accessed 10 Nov 2014];Tabacaleras se ajustan ante nueva ley. El Financiero. 2012 http://www.elfinancierocr.com/negocios/tabacaleras-ajustan-nueva-ley_0_170982910.html.

- 33.Cabezas Y. [accessed 28 Aug 2014];Pese a Ley de Tabaco, usuarios siguen fumando en lugares públicos. Crhoy. 2014 http://www.crhoy.com/pese-a-ley-de-tabaco-usuarios-siguen-fumando-en-lugares-publicos-w4l7m2x/

- 34.Herrera M. [accessed 25 Aug 2014];Salud tomo por sorpresa a bares y restaurants de Montes de Oca. La Nacion. 2012 http://www.nacion.com/archivo/Salud-sorpresa-restaurantes-Montes-Oca_0_1302669866.html.

- 35.Sandi L. Instituto de Alcoholismo y Farmacodependencia. San José; Costa Rica: Nov 7, 2014. Interview by Eric Crosbie. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saravia S. Hospital México. San José; Costa Rica: Nov 10, 2014. Interview by Eric Crosbie. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amador N. Ministerio de Salud. San José; Costa Rica: Nov 10, 2014. Interview by Eric Crosbie. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker L. Interview by Eric Crosbie. Ministerio de Salud, San José; Costa Rica: Nov 10, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zamora G. Interview by Eric Crosbie. En Comunicación, San José; Costa Rica: Nov 10, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gray K. [accessed 17 Aug 2014];Salud libra a tabacalera de multa de ¢3,6 millones. Diario Extra. 2013 http://www.diarioextra.com/Dnew/noticiaDetalle/40908.

- 41.Chavarria E. Letter from Edwin Chavarria to Health Minister Daisy Corrales concerning the ban on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship at the point of sale. Ministerio de Salud, San José; Costa Rica: Sep 26, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corrales D. Directive on the Interpretation of Tobacco Advertising at the Point of Sale in Law 9028. Ministerio de Salud, San José; Costa Rica: Oct 1, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cabrera O, Sosa P, Bianco E, et al. Cabrera O, Sosa P, Bianco E, et al. Letter from International Health Groups to Health Minister Maria Elena Lopez Nuñez about the prohibition of TAPS at the POS. Ministerio de Salud, San José; Costa Rica: May 28, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Castro R. Letter from Roberto Castro (RENATA) to Health Minister Maria Elena Lopez Nuñez regarding tobacco advertising at the point of sale. Ministerio de Salud, San José; Costa Rica: Sep 20, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Castro R. Letter from Roberto Castro (RENATA) to Dr. Fernando Llorca Castro regarding tobacco advertising at the point of sale. Ministerio de Salud, San José; Costa Rica: Jan 27, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Inside Costa Rica [accessed 20 Nov 2014];Costa Rica Cigarettes Will Continue Among the Cheapest in Latin America. 2012 http://www.insidecostarica.com/dailynews/2012/april/09/costarica12040902.htm.

- 47.World Health Organization . Decision: Electronic nicotine delivery systems and electronic non-nicotine delivery systems. Moscow; Russian Federation: Oct 18, 2014. Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dyer Z. Tico Times. Mar 26, 2014. Is Costa Rica's anti-tobacco law encouraging smuggling? [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arguedas C. La Nacion. Aug 21, 2013. Decomiso de cigarrillos ilegales se disparó durante último año. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quiros J. [accessed 21 Aug 2014];Fuerte norma antitabaco entrará a regir a fin de mes. La Nacion. 2013 http://www.nacion.com/nacional/comunidades/Fuerte-norma-antitabaco-entrara-regir_0_1348265383.html.

- 51.Rodriguez M. Letter from Marvin Rodriguez to Sissy Castillo regarding the Health Warning Label Regulations. Ministerio de Salud, San José; Costa Rica: Sep 11, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lambert P, Cabrera O. Letter from Patricia Lambert and Oscar Cabrera to Sissy Castillo concerning the legal implications of cigarette package health warning labels. Ministerio de Salud, San José; Costa Rica: Oct 24, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Castillo S. Letter from Sissy Castillo to Marvin Rodriguez regarding the Health Warning Label Regulations. Ministerio de Salud, San José; Costa Rica: Oct 17, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gray K. [accessed 14 Aug 2014];Salud incumple ley antitabaco. Diario Extra. 2013 http://www.diarioextra.com/Dnew/noticiaDetalle/1411.

- 55.Font A. [accessed 14 Aug 2014];Where are the warning labels on cigarette packs? Tico Times. 2013 http://www.ticotimes.net/2013/04/16/where-are-the-warning-labels-on-cigarette-packs.

- 56.Rodriguez I. [accessed 14 Aug 2014];Diputados urgen por advertencias gráficas en cajetillas de cigarrillos. La Nacion. 2013 http://www.nacion.com/archivo/Reglamento-dictamino-presidenta-Republica-Salud_0_1335666437.html.

- 57.Rodriguez I. [accessed 14 Aug 2014];Cajas de cigarros carecen de advertencias sobre daños a la salud. La Nacion. 2013 http://www.nacion.com/2013–04–16/ElPais/Cajas-de-cigarros-carecen-de-advertencias-sobre-danos-a-la-salud.aspx.

- 58.Kellett G, Huber L, Myers M, et al. Letter from international health groups to President Laura Chinchilla concerning the regulation of cigarette package health warning labels. Poder ejecutivo, San José; Costa Rica: Apr 15, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 59.La Presidenta de la República y la Ministra de Salud . Reglamento para las Etiquetas de las Advertencias Sanitarias. Ministerio de Salud, San José; Costa Rica: Jul 9, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mora P. [accessed 28 Aug 2014];Costa Rica: cajetillas de cigarros tendrán fotos con efectos del tabaco. CB24. 2013 http://cb24.tv/costa-rica-cajetillas-de-cigarros-tendran-fotografias-con-efectos-del-tabaco/

- 61.Gray K. Aprueban transición a etiquetas de cigarrillos. Diario Extra. 2014 http://www.diarioextra.com/Noticia/detalle/240547/aprueban-transicion-a-etiquetas-de-cigarrillos.

- 62.Lie JL, Willemsen MC, de Vries NK, et al. Tob Control. 2015. The devil is in the detail: tobacco industry political influence in the Dutch implementation of the 2001 EU Tobacco Products Directive. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stark MJ, Rohde K, Maher JE, et al. The impact of clean indoor air exemptions and preemption policies on the prevalence of a tobacco-specific lung carcinogen among nonsmoking bar and restaurant workers. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1457–63. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.094086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Siegel M, Skeer M. Exposure to secondhand smoke and excess lung cancer mortality risk among workers in the “5 B's”: bars, bowling alleys, billiard halls, betting establishments, and bingo parlours. Tob Control. 2003;12:333–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Edwards R, Thomson G, Wilson N, et al. After the smoke has cleared: evaluation of the impact of a new national smoke-free law in New Zealand. Tob Control. 2008;17:e2. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gonzalez M, Glantz SA. Failure of policy regarding smoke-free bars in the Netherlands. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23:139–45. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sebrie EM, Schoj V, Travers MJ, et al. Smokefree policies in Latin America and the Caribbean: making progress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:1954–70. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9051954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gilmore AB, Fooks G, Drope J, et al. Exposing and addressing tobacco industry conduct in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2015;385:1029–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60312-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Peeters S, Costa H, Stuckler D, et al. The revision of the 2014 European tobacco products directive: an analysis of the tobacco industry's attempts to `break the health silo'. Tob Control. 2016;25:108–17. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ulucanlar S, Fooks GJ, Hatchard JL, et al. Representation and misrepresentation of scientific evidence in contemporary tobacco regulation: a review of tobacco industry submissions to the UK Government consultation on standardised packaging. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bryan-Jones K, Bero LA. Tobacco industry efforts to defeat the occupational safety and health administration indoor air quality rule. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:585–92. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hiilamo H, Glantz SA. Old wine in new bottles: tobacco industry's submission to European Commission tobacco product directive public consultation. Health Policy. 2015;119:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chandora RD, Whitney CF, Weaver SR, et al. Changes in Georgia restaurant and bar smoking policies from 2006 to 2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E74. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.140520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McCaffrey M, Goodman P, Gavigan A, et al. Should any workplace be exempt from smoke-free law: the Irish experience. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:545483. doi: 10.1155/2012/545483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Samuels B, Glantz SA. The politics of local tobacco control. JAMA. 1991;266:2110–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Scollo M, Lal A, Hyland A, et al. Review of the quality of studies on the economic effects of smoke-free policies on the hospitality industry. Tob Control. 2003;12:13–20. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Glantz SA. Effect of smokefree bar law on bar revenues in California. Tob Control. 2000;9:111–12. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.1.111a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Collins NM, Shi Q, Forster JL, et al. Effects of clean indoor air laws on bar and restaurant revenue in Minnesota cities. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(6 Suppl 1):S10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dearlove JV, Bialous SA, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry manipulation of the hospitality industry to maintain smoking in public places. Tobacco Control. 2002;11:94–104. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.2.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ritch WA, Begay ME. Strange bedfellows: the history of collaboration between the Massachusetts Restaurant Association and the tobacco industry. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:598–603. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.4.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gilmore AB, Rowell A, Gallus S, et al. Towards a greater understanding of the illicit tobacco trade in Europe: a review of the PMI funded `Project Star' report. Tob Control. 2014;23(e1):e51–61. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Howell F. The Irish tobacco industry position on price increases on tobacco products. Tob Control. 2012;21:514–16. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Joossens L, Raw M. Turning off the tap: the real solution to cigarette smuggling. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003;7:214–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Joossens L, Raw M. How can cigarette smuggling be reduced? BMJ. 2000;321:947–50. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7266.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alemanno A. Legality, rationale and science of tobacco display bans after the philip morris jugment. Eur J Risk Reg. 2011;1:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 86. [accessed 10 Feb 2015];Tobacco display ban in Scotland to begin in April 2013. BBC. 2012 http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-20691956.

- 87.Brown J. [accessed 22 Nov 2014];Top court upholds tobacco ad rules. The Star. 2007 http://www.thestar.com/news/2007/06/28/top_court_upholds_tobacco_ad_rules.html.

- 88. [accessed 10 Nov 2014];Norway court upholds ban on tobacco store displays. USA Today. 2012 http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/world/story/2012/09/14/norway-court-upholds-ban-on-tobacco-store-displays/57782130/1.

- 89.Liberman J. Plainly constitutional: the upholding of plain tobacco packaging by the High Court of Australia. Am J Law Med. 2013;39:361–81. doi: 10.1177/009885881303900209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. [accessed 20 Nov 2014];Lefevre AS. Bigger health warnings for Thai cigarette packs. Reuters. 2014 http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/06/27/us-thailand-cigarettes-idUSKBN0F21AC20140627.

- 91.Helbling W. [accessed 10 Jan 2015];Thailand court approves graphic warnings on cigarette packages. Jurist. 2014 http://jurist.org/paperchase/2014/06/thailand-court-approves-graphic-warnings-on-cigarette-packages.php.

- 92.Crosbie E, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry argues domestic trademark laws and international treaties preclude cigarette health warning labels, despite consistent legal advice that the argument is invalid. Tob Control. 2014;23:e7. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hiilamo H, Crosbie E, Glantz SA. The evolution of health warning labels on cigarette packs: the role of precedents, and tobacco industry strategies to block diffusion. Tob Control. 2014;23:e2. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McKay B. [accessed 19 Mar 2015];Bloomberg, Gates Launch Antitabaco Fund. Wall Street Journal. 2015 http://www.wsj.com/articles/bloomberg-gates-launch-antitobacco-fund-1426703947.

- 95.World Health Organization . Guidelines for Implementation of Article 5.3 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control on the protection of public health policies with respect to tobacco control from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry. Geneva: Switzerland: Nov, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fooks GJ, Gilmore AB, Smith KE, et al. Corporate social responsibility and access to policy elites: an analysis of tobacco industry documents. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kashiwabara M, Armada F. Mind your “smoking manners”: the tobacco industry tactics to normalize smoking in Japan. Kobe J Med Sci. 2013;59:E132–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hirschhorn N. Corporate social responsibility and the tobacco industry: hope or hype? Tob Control. 2004;13:447–53. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chapman S. Advocacy in action: extreme corporate makeover interruptus: denormalising tobacco industry corporate schmoozing. Tob Control. 2004;13:445–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.010025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lee S, Ling PM, Glantz SA. The vector of the tobacco epidemic: tobacco industry practices in low and middle-income countries. Cancer Causes Control 2012. 23(Suppl 1):117–29. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9914-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Assunta M, Dorotheo EU. SEATCA Tobacco Industry Interference Index: a tool for measuring implementation of WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Article 5.3. Tob Control. 2015 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hurt RD, Ebbert JO, Achadi A, et al. Roadmap to a tobacco epidemic: transnational tobacco companies invade Indonesia. Tob Control. 2012;21:306–12. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.036814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Assunta M, Chapman S. Industry sponsored youth smoking prevention programme in Malaysia: a case study in duplicity. Tob Control. 2004;13(Suppl 2):ii37–42. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.007732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sebrie EM, Blanco A, Glantz SA. Cigarette labeling policies in Latin America and the Caribbean: progress and obstacles. Salud Pública de México. 2010;52:S233–43. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342010000800019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Otanez M, Glantz SA. Social responsibility in tobacco production? Tobacco companies' use of green supply chains to obscure the real costs of tobacco farming. Tob Control. 2011;20:403–11. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.039537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Otanez MG, Muggli ME, Hurt RD, et al. Eliminating child labour in Malawi: a British American Tobacco corporate responsibility project to sidestep tobacco labour exploitation. Tob Control. 2006;15:224–30. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cavalcante T, Carvalho Ade M, et al. Social responsibility argument for the tobacco industry in Brazil. Salud Publica Mex. 2006;48(Suppl 1):S173–182. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342006000700021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chaloupka FJ, Yurekli A, Fong GT. Tobacco taxes as a tobacco control strategy. Tob Control. 2012;21:172–80. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Farrelly MC, Pechacek TF, Chaloupka FJ. The impact of tobacco control program expenditures on aggregate cigarette sales: 1981–2000. J Health Econ. 2003;22:843–59. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(03)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Farrelly MC, Pechacek TF, Thomas KY, et al. The impact of tobacco control programs on adult smoking. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:304–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.106377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tauras JA, Chaloupka FJ, Farrelly MC, et al. State tobacco control spending and youth smoking. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:338–44. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.039727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Champagne BM, Sebrie E, Schoj V. The role of organized civil society in tobacco control in Latin America and the Caribbean. Salud Publica Mex. 2010;52(Suppl 2):S330–339. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342010000800031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]