Case Presentation and Evolution

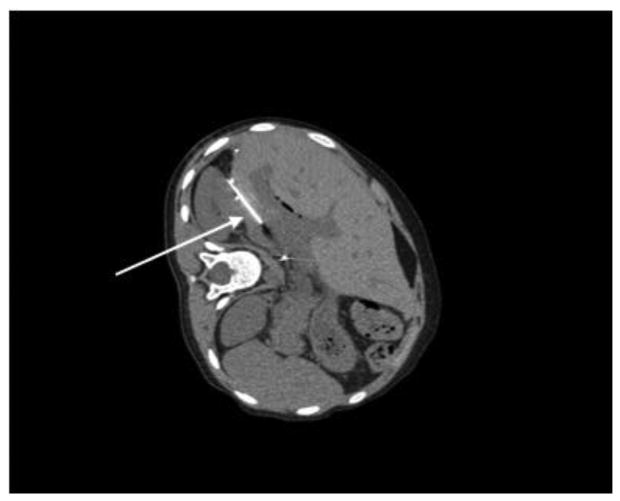

A 10-year-old girl with biliary atresia who underwent orthotopic liver transplant July, 2012 was initially evaluated by our institution one year after transplant with two weeks of daily fevers up to 104° C. She had associated fatigue, abdominal pain, and anorexia, but denied emesis, changes in bowel movements, dysuria, cough, rash, or rhinorrhea. She was fully vaccinated pre-transplant, and had no animal exposures or travel outside of the United States. Her post-liver transplant course was complicated by an episode of acute rejection one month after transplant, as well as by hepatic artery stenosis. Her immunosuppressive medications were tacrolimus and sirolimus, with supratherapeutic serum concentrations requiring dosage reduction several weeks prior to admission. Hospital admission laboratories were notable for mild leukopenia (white blood cell count 2.2), elevated C-reactive protein (16.9, normal <0.2), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 76, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 91, and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) 69. Urinalysis and lipase were normal. Initial infectious evaluation was negative for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or cytomegalovirus (CMV) in serum as detected by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and for bacterial culture, Clostridium difficile toxin, and ova and parasites in stool. An abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a 3.7cm × 2.5cm × 2.4 cm fluid collection in the liver, concerning for pyogenic abscess (Figure 1A and 1B). Interventional radiology performed a computed tomography (CT)-guided drainage of the fluid collection as well as a liver biopsy (Figure 2). Serum adenovirus PCR was then noted to be significantly elevated at 21,700 viral copies/milliliter (mL). Liver tissue surrounding the aspirated fluid collection showed hepatic necrosis with positive immunohistochemical staining for adenovirus (Figure 3). The liver biopsy showed portal inflammation with granulomata, but negative adenovirus immunohistochemical staining. PCR of urine for adenovirus was positive, stool adenovirus antigen was negative, and respiratory viral PCR testing was negative for adenovirus. An extensive infectious work-up was performed and was negative, including hepatitis A, B and C serologies, bartonella titers, coccidiodomycosis titers, brucella antibody, coxiella titers, histoplasma antigen, toxoplasmosis antibody, HIV western blot, rapid plasma reagin (RPR), and QuantiFERON®-TB gold. Bacterial and fungal cultures of the blood and the liver abscess aspirate were negative. Liver tissue fungal stains and acid-fast bacilli stains were also negative.

Figure 1. Abdominal MRI post-contrast images of hepatic abscess in axial (A) and coronal (B) views.

Figure 2. Abdominal CT demonstrating interventional radiology needle drainage of hepatic abscess.

Figure 3. Histology demonstrating positive adenovirus immunohistochemical staining of hepatic tissue.

The patient became afebrile with improvement in AST to 48, although slight increases in the ALT (to 115) and GGT (to 98) were noted following the liver abscess drainage. Normalization of the AST to 23 and ALT to 50 were noted ∼ 2 weeks after her initial presentation. Treatment included careful reduction of her immunosuppression, but no antiviral therapy was given. Her adenovirus PCR continued to downtrend as an outpatient to 540 viral copies/mL after two weeks, and to undetectable concentrations six weeks after her initial presentation. Repeat abdominal MRI six weeks after initial presentation showed near resolution of the hepatic fluid collection.

Discussion

Adenovirus is a double stranded DNA virus with 51 serotypes that accounts for 5 - 10% of all febrile illnesses in infants and young children. It most commonly causes pharyngitis or coryza, but can also cause pneumonia, gastrointestinal, ophthalmologic, genitourinary, and neurologic disease. Adenovirus can be transmitted by aerosol droplets, fecal-oral route, or contact with contaminated fomites.1 Adenoviral infection in post-transplant patients can range from asymptomatic shedding to disseminated fatal disease. The adenoviral infection, which typically involves the transplanted organ, can be either a primary infection or a reactivation of a latent infection in the host or donor organ. One retrospective review of 484 liver transplant recipients documented 20 episodes of invasive adenovirus disease in children resulting in 9 deaths, and 14 patients with adenoviral hepatitis, 4 of whom recovered.2 Adenoviral infections typically occur within the first month after transplant when immunosuppression is the greatest.3 Pediatric intestinal transplant patients also have an increased risk of adenovirus infection, likely related to increased immunosuppression.3 Treatment of adenoviral infection in post-transplant patients primarily involves reduction in immunosuppression. Cidofovir is typically reserved for severe disseminated disease given its risk of nephrotoxicity and neutropenia.1, 3

Liver abscess, rare in developed nations, accounts for 25 of 100,000 pediatric hospital admission in the US, compared to 1 in 140 hospital admissions in Brazil.4,5 Risk factors for hepatic abscess include immunosuppression, underlying biliary or hepatic disease, malnutrition, trauma, or immunodeficiency.4,5 Pyogenic liver abscess is the most common etiology with Staphylococcus aureus as the most common pathogen worldwide.6,7 Pyogenic liver abscesses are often polymicrobial, with other common bacterial pathogens including Klebsiella species, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter species, and Salmonella typhi. Fungal and tubercular abscesses are less common, and viral abscesses are exceedingly rare.6,7 Typical presentation includes fever, abdominal pain and anorexia with leukocytosis, elevated ESR, and elevated liver function tests. Diagnosis is confirmed with imaging including ultrasound, CT, or MRI. Diagnostic and therapeutic drainage is required in 80-90% of pediatric cases, with percutaneous aspiration being the most commonly used.6,7 Treatment, dependent on the causative organism, is often a prolonged course of several weeks of IV antibiotics or antifungals. Complications of hepatic abscess include sepsis, empyema, peritonitis, hepatobronchial fistula, and Budd-Chiari syndrome.

We describe a novel finding of adenovirus hepatic abscess in a pediatric liver transplant patient whose initial manifestation was fever of unknown origin. We hypothesize that our patient's prior supratherapeutic immunosuppression and possibly an initial insult to the liver parenchyma from hepatic artery stenosis post-transplant predisposed her to adenoviral infection and hepatic abscess formation. Though adenoviral disease and hepatic abscess are well-described infections in the liver transplant recipient population, we believe this is the first report of hepatic abscess caused by adenovirus. We propose that adenovirus should become part of the differential diagnosis of possible etiologies of hepatic abscess, particularly in an immunosuppressed patient.

Key Messages.

Hepatic abscess should be considered as a possible source of prolonged fever, particularly in a post-transplant patient

Adenovirus is a common pathogen among children, but can cause severe disseminated disease or have an atypical presentation in post-transplant patients including hepatic abscess

Treatment of adenovirus infection in post-transplant patients involves reduction of immunosuppression, supportive care, and Cidofovir in severe cases

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics. Adenovirus Infections. In: Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, editors. Red Book®: 2015 REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON INFECTIOUS DISEASES. Vol. 2015. American Academy of Pediatrics; pp. 226–228. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michaels MG, Green M, Wald ER, Starzl TE. Adenovirus Infection in Pediatric Liver Transplant Recipients. J Infect Dis. 1992;165(1):170. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.1.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Florescu DF, Hoffman JA. Adenovirus in Solid Organ Transplant. Am J Transplant. 2013 Mar 13;4(Suppl 4):206–11. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan GG, Gregson DB, Laupland KB. Population-based study of the epidemiology of and the risk factors for pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1032. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00459-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nikeghbalian S, Salahi R, Salahi H, Bahador A, Kakaie F, Kazemi K, Malek-Hosseini SA, Janghorban P. Hepatic abscesses after liver transplant: 1997-2008. Exp Clin Transplant. 2009 Dec;7(4):256–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mishra K, Basu S, Roychoudhury S, Kumar P. Liver abscess in children: an overview. World J Pediatr. 2010;6(3):2010–216. doi: 10.1007/s12519-010-0220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma MP, Kumar A. Liver Abscess in Children. Indian J of Pediatrics. 2006;73(9):813–817. doi: 10.1007/BF02790392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]