Abstract

Background

Acupuncture is often used for migraine prevention but its effectiveness is still controversial. We present an update of our Cochrane review from 2009.

Objectives

To investigate whether acupuncture is a) more effective than no prophylactic treatment/routine care only; b) more effective than sham (placebo) acupuncture; and c) as effective as prophylactic treatment with drugs in reducing headache frequency in adults with episodic migraine.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL: 2016, issue 1); MEDLINE (via Ovid, 2008 to January 2016); Ovid EMBASE (2008 to January 2016); and Ovid AMED (1985 to January 2016). We checked PubMed for recent publications to April 2016. We searched the World Health Organization (WHO) Clinical Trials Registry Platform to February 2016 for ongoing and unpublished trials.

Selection criteria

We included randomized trials at least eight weeks in duration that compared an acupuncture intervention with a no‐acupuncture control (no prophylactic treatment or routine care only), a sham‐acupuncture intervention, or prophylactic drug in participants with episodic migraine.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers checked eligibility; extracted information on participants, interventions, methods and results, and assessed risk of bias and quality of the acupuncture intervention. The primary outcome was migraine frequency (preferably migraine days, attacks or headache days if migraine days not measured/reported) after treatment and at follow‐up. The secondary outcome was response (at least 50% frequency reduction). Safety outcomes were number of participants dropping out due to adverse effects and number of participants reporting at least one adverse effect. We calculated pooled effect size estimates using a fixed‐effect model. We assessed the evidence using GRADE and created 'Summary of findings' tables.

Main results

Twenty‐two trials including 4985 participants in total (median 71, range 30 to 1715) met our updated selection criteria. We excluded five previously included trials from this update because they included people who had had migraine for less than 12 months, and included five new trials. Five trials had a no‐acupuncture control group (either treatment of attacks only or non‐regulated routine care), 15 a sham‐acupuncture control group, and five a comparator group receiving prophylactic drug treatment. In comparisons with no‐acupuncture control groups and groups receiving prophylactic drug treatment, there was risk of performance and detection bias as blinding was not possible. Overall the quality of the evidence was moderate.

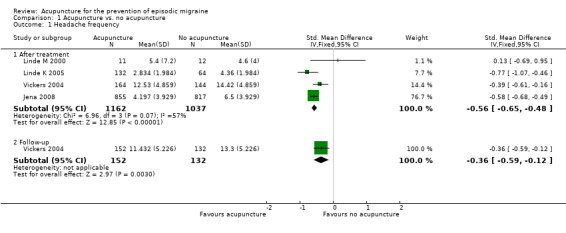

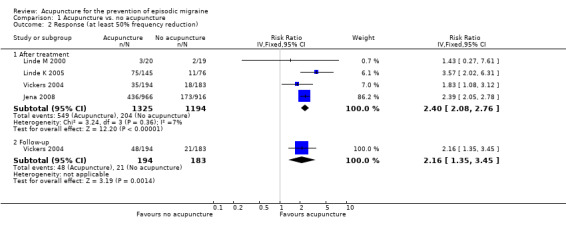

Comparison with no acupuncture

Acupuncture was associated with a moderate reduction of headache frequency over no acupuncture after treatment (four trials, 2199 participants; standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.56; 95% CI ‐0.65 to ‐0.48); findings were statistically heterogeneous (I² = 57%; moderate quality evidence). After treatment headache frequency at least halved in 41% of participants receiving acupuncture and 17% receiving no acupuncture (pooled risk ratio (RR) 2.40; 95% CI 2.08 to 2.76; 4 studies, 2519 participants) with a corresponding number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) of 4 (95% CI 3 to 6); there was no indication of statistical heterogeneity (I² = 7%; moderate quality evidence). The only trial with post‐treatment follow‐up found a small but significant benefit 12 months after randomisation (RR 2.16; 95% CI 1.35 to 3.45; NNT 7; 95% 4 to 25; 377 participants, low quality evidence).

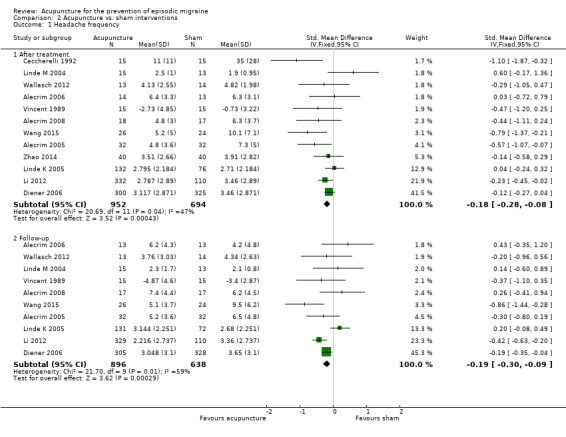

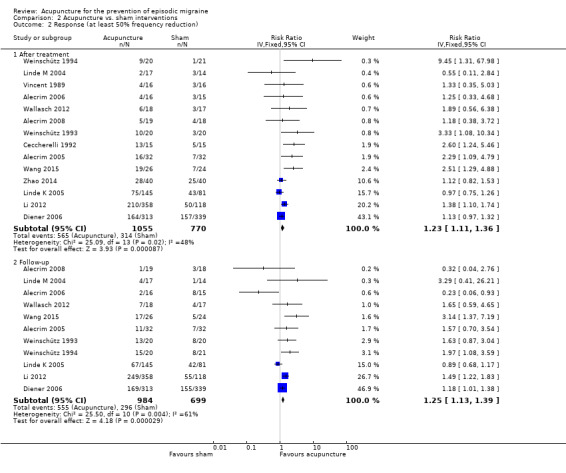

Comparison with sham acupuncture

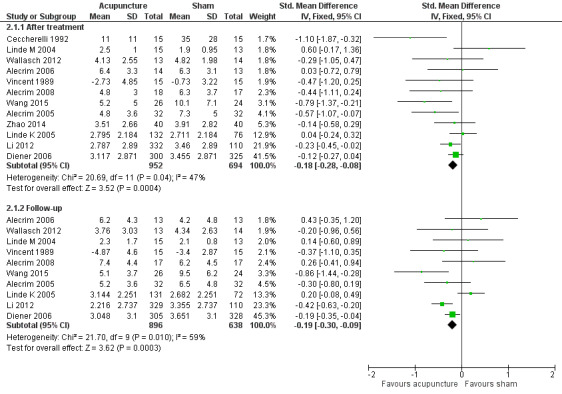

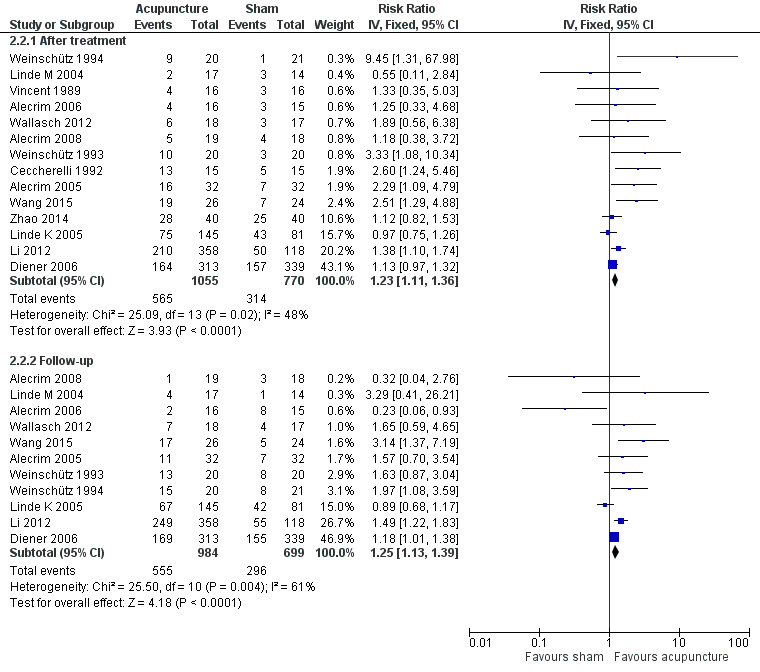

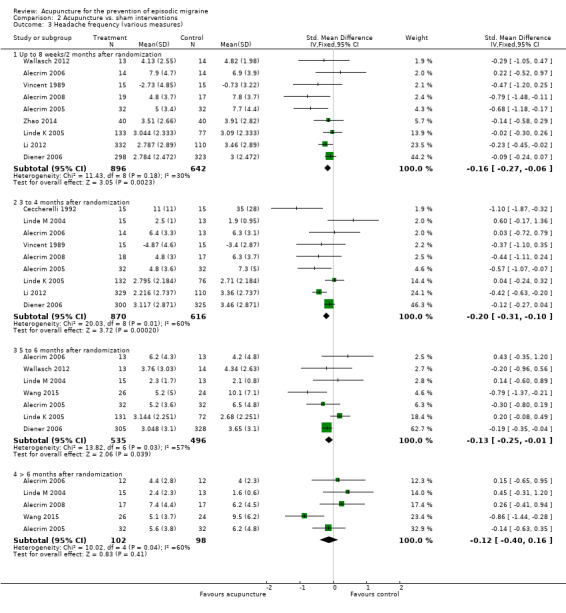

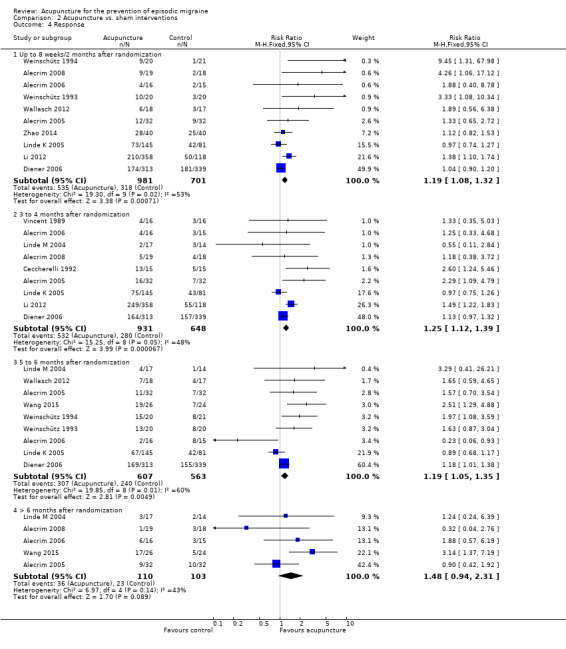

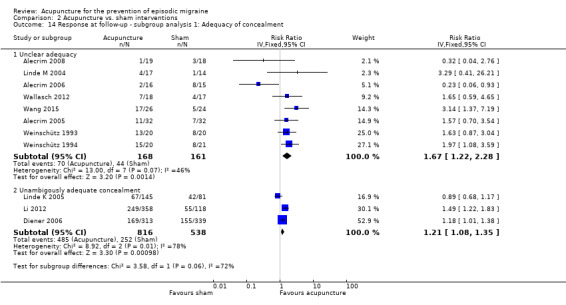

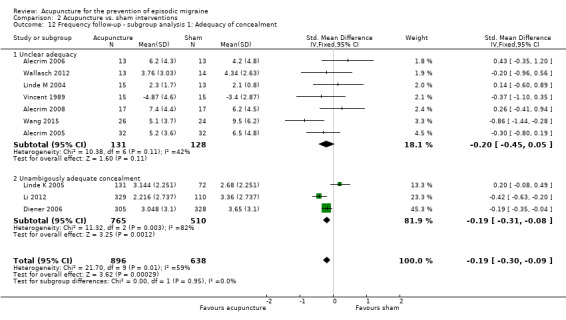

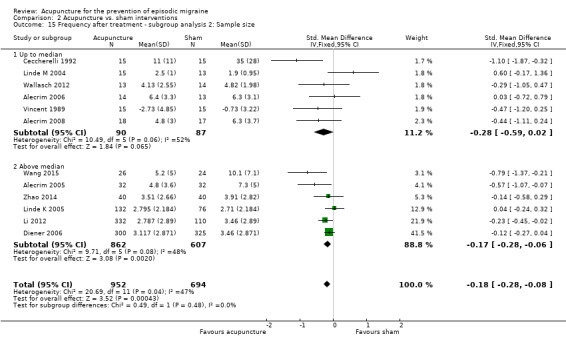

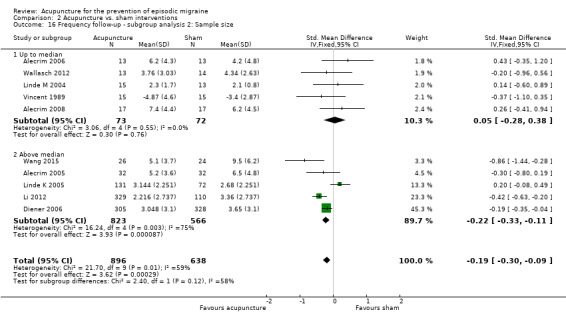

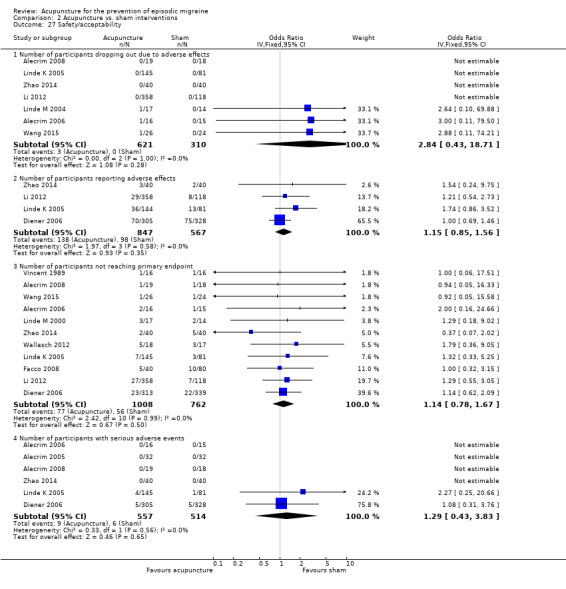

Both after treatment (12 trials, 1646 participants) and at follow‐up (10 trials, 1534 participants), acupuncture was associated with a small but statistically significant frequency reduction over sham (moderate quality evidence). The SMD was ‐0.18 (95% CI ‐0.28 to ‐0.08; I² = 47%) after treatment and ‐0.19 (95% CI ‐0.30 to ‐0.09; I² = 59%) at follow‐up. After treatment headache frequency at least halved in 50% of participants receiving true acupuncture and 41% receiving sham acupuncture (pooled RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.36; I² = 48%; 14 trials, 1825 participants) and at follow‐up in 53% and 42%, respectively (pooled RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.39; I² = 61%; 11 trials, 1683 participants; moderate quality evidence). The corresponding NNTBs are 11 (95% CI 7.00 to 20.00) and 10 (95% CI 6.00 to 18.00), respectively. The number of participants dropping out due to adverse effects (odds ratio (OR) 2.84; 95% CI 0.43 to 18.71; 7 trials, 931 participants; low quality evidence) and the number of participants reporting adverse effects (OR 1.15; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.56; 4 trials, 1414 participants; moderate quality evidence) did not differ significantly between acupuncture and sham groups.

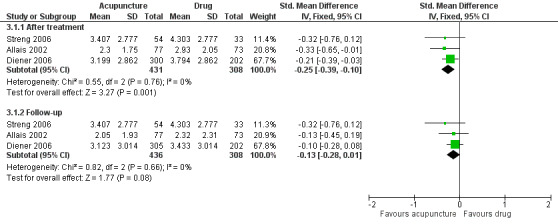

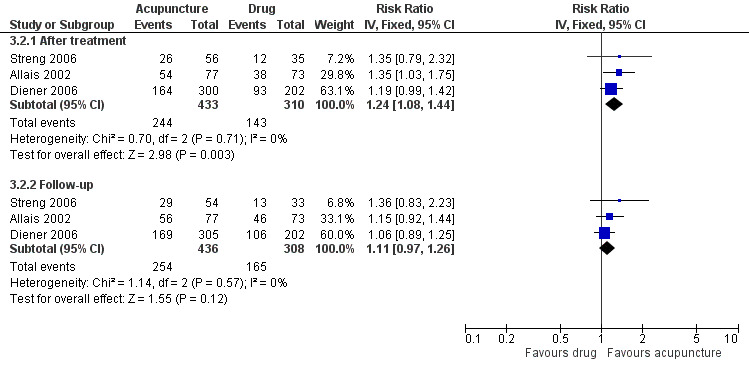

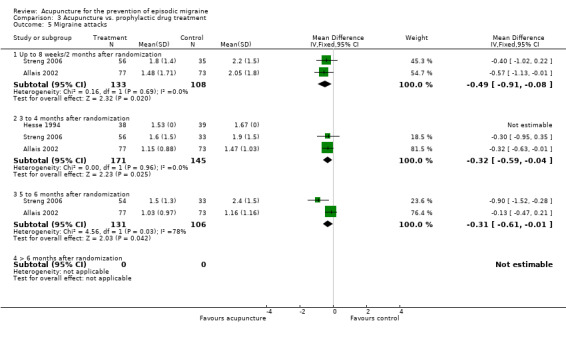

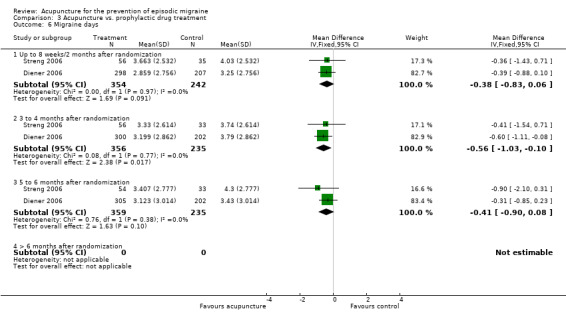

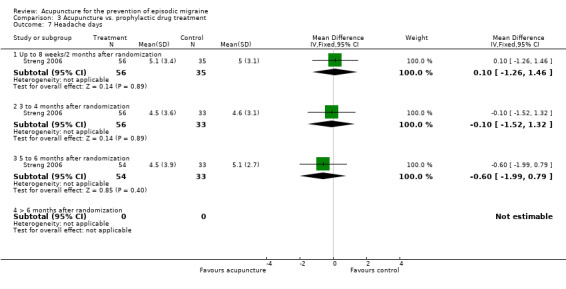

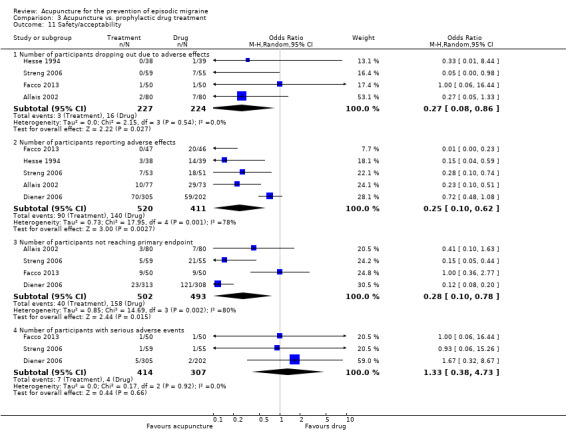

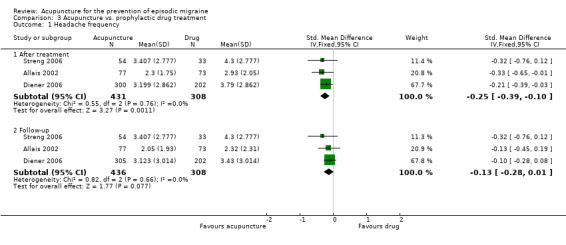

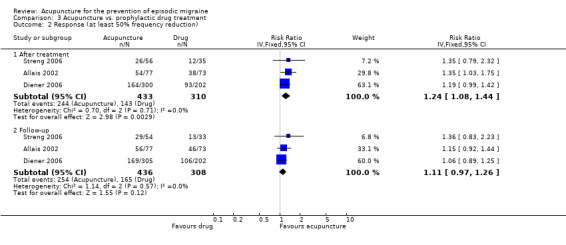

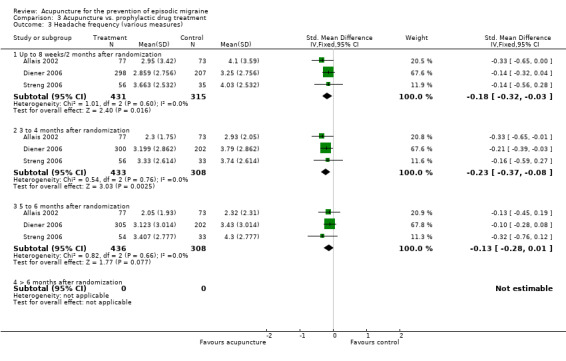

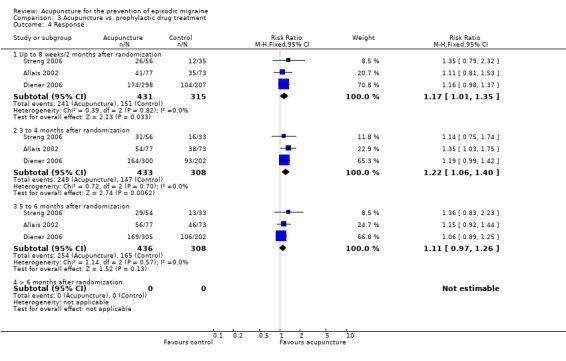

Comparison with prophylactic drug treatment

Acupuncture reduced migraine frequency significantly more than drug prophylaxis after treatment ( SMD ‐0.25; 95% CI ‐0.39 to ‐0.10; 3 trials, 739 participants), but the significance was not maintained at follow‐up (SMD ‐0.13; 95% CI ‐0.28 to 0.01; 3 trials, 744 participants; moderate quality evidence). After three months headache frequency at least halved in 57% of participants receiving acupuncture and 46% receiving prophylactic drugs (pooled RR 1.24; 95% CI 1.08 to 1.44) and after six months in 59% and 54%, respectively (pooled RR 1.11; 95% CI 0.97 to 1.26; moderate quality evidence). Findings were consistent among trials with I² being 0% in all analyses. Trial participants receiving acupuncture were less likely to drop out due to adverse effects (OR 0.27; 95% CI 0.08 to 0.86; 4 trials, 451 participants) and to report adverse effects (OR 0.25; 95% CI 0.10 to 0.62; 5 trials 931 participants) than participants receiving prophylactic drugs (moderate quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

The available evidence suggests that adding acupuncture to symptomatic treatment of attacks reduces the frequency of headaches. Contrary to the previous findings, the updated evidence also suggests that there is an effect over sham, but this effect is small. The available trials also suggest that acupuncture may be at least similarly effective as treatment with prophylactic drugs. Acupuncture can be considered a treatment option for patients willing to undergo this treatment. As for other migraine treatments, long‐term studies, more than one year in duration, are lacking.

Keywords: Female, Humans, Male, Acupuncture Therapy, Acupuncture Therapy/adverse effects, Migraine Disorders, Migraine Disorders/drug therapy, Migraine Disorders/prevention & control, Migraine with Aura, Migraine with Aura/prevention & control, Migraine without Aura, Migraine without Aura/prevention & control, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Acupuncture for preventing migraine attacks

Bottom line

The available evidence suggests that a course of acupuncture consisting of at least six treatment sessions can be a valuable option for people with migraine.

Background

Individuals with migraine have repeated attacks of severe headache, usually just on one side and often with vomiting. Acupuncture is a therapy in which thin needles are inserted into the skin at particular points. It originated in China, and is now used in many countries to treat people with migraine. We evaluated whether acupuncture reduces the number of episodes of migraine. We looked at the number of people in whom the number of migraine days per month was reduced by half or more than half.

Key results

For this update, we reviewed 22 trials with 4985 people, published up to January 2016. We omitted five trials from the original review because they included people who had had migraine for less than 12 months. We included five new trials in this update.

In four trials, acupuncture added to usual care or treatment of migraine on onset only (usually with pain‐killers) resulted in 41 in 100 people having the frequency of headaches at least halved, compared to 17 of 100 people given usual care only.

In 15 trials, acupuncture was compared with 'fake' acupuncture, where needles are inserted at incorrect points or do not penetrate the skin. The frequency of headaches halved in 50 of 100 people receiving true acupuncture, compared with 41 of 100 people receiving 'fake' acupuncture. The results were dominated by three good quality large trials (with about 1200 people) showing that the effect of true acupuncture was still present after six months. There were no differences in the number of side effects of real and 'fake' acupuncture, or the numbers dropping out because of side effects.

In five trials, acupuncture was compared to a drug proven to reduce the frequency of migraine attacks, but only three trials provided useful information. At three months, headache frequency halved in 57 of 100 people receiving acupuncture, compared with 46 of 100 people taking the drug. After six months, headache frequency halved in 59 of 100 people receiving acupuncture, compared with 54 of 100 people taking the drug. People receiving acupuncture reported side effects less often than people receiving drugs, and were less likely to drop out of the trial.

Our findings about the number of days with migraine per month can be summarized as follows. If people have six days with migraine per month on average before starting treatment, this would be reduced to five days in people receiving only usual care, to four days in those receiving fake acupuncture or a prophylactic drug, and to three and a half days in those receiving true acupuncture.

Quality of the evidence

Overall the quality of the evidence was moderate.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Acupuncture compared to no treatment/usual care.

| Acupuncture compared to no treatment/usual care | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with episodic migraine Setting: primary care or outpatient care Intervention: acupuncture Comparison: no treatment/usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no treatment/usual care | Risk with Acupuncture | |||||

| Headache frequency (after treatment)

assessed with days per month follow‐up: median 3 months |

Headache frequency was 0.56 SDs (‐0.65 to ‐0.48) lower than in the groups receiving no/usual treatment | ‐ | 2199 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 2 | As a rule of thumb 0.2 SD represents a small difference, 0.5 a moderate, and 0.8 a large difference. Size of difference open to change with more trials | |

| Headache frequency (follow‐up)

assessed with days per month follow‐up: 12 months |

Headache frequency was 0.36 SDs (‐0.59 to ‐0.12) lower than in the groups receiving no/usual treatment | ‐ | 284 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | Only single large trial available. As a rule of thumb 0.2 SD represents a small difference, 0.5 a moderate, and 0.8 a large difference. Size of difference open to change with more trials. | |

| Response (after treatment)

assessed with proportion of participants with at least 50% headache frequency reduction follow‐up: median 3 months |

Study population | RR 2.40 (2.08 to 2.76) | 2519 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | No blinding, variable care in control groups, variable size of effects, but moderate to large effects in all three larger trials | |

| 171 per 1000 | 410 per 1000 (355 to 472) | |||||

| Response (follow‐up)

assessed with proportion of participants with at least 50% headache frequency reduction follow‐up: 12 months |

Study population | RR 2.16 (1.35 to 3.45) | 377 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | Only single large trial available | |

| 98 per 1000 | 212 per 1000 (133 to 339) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Interventions in control groups and study findings variable (I² = 57%; Chi² = 6.96, P value = 0.07), but effects moderate to large in all three larger trials

2 Downgraded once: no blinding

3 Downgraded once: only one study

Summary of findings 2. Acupuncture compared to sham interventions.

| Acupuncture compared to sham acupuncture | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with episodic migraine Setting: primary care or outpatient care Intervention: acupuncture Comparison: sham acupuncture | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with sham acupuncture | Risk with Acupuncture | |||||

| Headache frequency (after treatment) assessed with days per month follow‐up: median 12 weeks | Headache frequency was 0.18 SDs (‐0.28 to ‐0.08) lower than in the groups receiving sham treatment | ‐ | 1646 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | As a rule of thumb 0.2 SD represents a small difference, 0.5 a moderate, and 0.8 a large difference | |

| Headache frequency (follow‐up) assessed with days per month follow‐up: median 6 months | Assuming a mean number of 3.5 (SD 3.0) migraine days in the sham group, participants in the acupuncture group would have 0.6 days (95% CI 0.3 to 1.1 days) less (SMD = ‐0.19; 95% CI ‐0.30 to ‐0.09; 896 patients receiving acupuncture, 638 sham) | ‐ | 1534 (10 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | As a rule of thumb 0.2 SD represents a small difference, 0.5 a moderate, and 0.8 a large difference | |

| Response (after treatment) assessed with proportion of participants with at least 50% headache frequency reduction follow‐up: median 12 weeks | Study population | RR 1.23 (1.11 to 1.36) | 1825 (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3 | Variable results between studies; modest effect size leaves magnitude of effect open to change with further large trials | |

| 408 per 1000 | 502 per 1000 (453 to 555) | |||||

| Response (follow‐up) assessed with proportion of participants with at least 50% headache frequency reduction follow‐up: median 6 months | Study population | RR 1.25 (1.13 to 1.39) | 1683 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 4 | Variable results between studies; modest effect size leaves magnitude of effect open to change with further large trials | |

| 423 per 1000 | 529 per 1000 (479 to 589) | |||||

| Number of participants dropping out due to adverse effects | Study population | RR 2.84 (0.43 to 18.71) | 931 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 5 | Relevant uncertainty due to low event rates | |

| Only 3/621 participants receiving acupuncture and 0/310 receiving sham dropped out due to adverse effects | ||||||

| Number of participants reporting adverse effects | Study population | RR 1.15 (0.85 to 1.56) | 1414 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Only 4 large trials report this outcome adequately; variable methods to document adverse effects, yet results of trials are consistent | |

| 173 per 1000 | 199 per 1000 (147 to 270) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded once: pronounced heterogeneity of study results (I² = 47%; Chi² = 20.69; P value = 0.04)

2 Downgraded once: pronounced heterogeneity of study results (I² = 59%; Chi² = 27.10; P value = 0.0003)

3 Downgraded once: pronounced heterogeneity of study results (I² = 48%; Chi² = 25.09; P value = 0.02)

4 Downgraded once: pronounced heterogeneity of study results (I² = 61%; Chi² = 25.50; P value = 0.004)

5 Downgraded twice: only very few events

Summary of findings 3. Acupuncture compared to prophylactic drugs.

| Acupuncture compared to prophylactic drugs | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with episodic migraine Setting: primary care or outpatient care Intervention: acupuncture Comparison: prophylactic drug treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with prophylactic drug treatment | Risk with acupuncture | |||||

| Headache frequency assessed with days per month follow‐up median 3 months | Headache frequency was 0.25 SDs (‐039 to ‐0.10) lower than in the groups receiving prophylactic drug treatment | ‐ | 739 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | As a rule of thumb 0.2 SD represents a small difference, 0.5 a moderate, and 0.8 a large difference. Size of difference open to change with more trials | |

| Headache frequency assessed with days per month follow‐up: median 6 months | Headache frequency was 0.13 SDs (‐0.28 to 0.01) lower than in the groups receiving prophylactic drug treatment | ‐ | 744 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | As a rule of thumb 0.2 SD represents a small difference, 0.5 a moderate, and 0.8 a large difference. Size of difference open to change with more trials | |

| Response assessed with proportion of participants with at least 50% headache frequency reduction follow‐up: median 3 months | Study population | RR 1.24 (1.08 to 1.44) | 743 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Due to the limited number of trials and risk of bias size of differences open to change with more trials | |

| 461 per 1000 | 572 per 1000 (498 to 664) | |||||

| Response assessed with proportion of participants with at least 50% headache frequency reduction follow‐up: median 6 months | Study population | RR 1.11 (0.97 to 1.26) | 744 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Due to the limited number of trials and risk of bias size of differences open to change with more trials | |

| 536 per 1000 | 595 per 1000 (520 to 675) | |||||

| Number of participants dropping out due to adverse effects | Study population | OR 0.27 (0.08 to 0.86) | 451 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | Consistent results between studies, but uncertainty about size of difference due to low frequency of events in acupuncture group | |

| 71 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (6 to 62) | |||||

| Number of participants reporting adverse effects | Study population | OR 0.25 (0.10 to 0.62) | 931 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3 | Consistently fewer adverse effects in acupuncture groups, but strong variability of size of differences (probably due to different assessment methods) | |

| 341 per 1000 | 114 per 1000 (49 to 243) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded once: in two of three studies a relevant proportion of participants randomized to drug treatment dropped out early (analysis included only participants receiving at least a minimal amount of treatment); no blinding of participants

2 Downgraded once: few events in acupuncture group; wide confidence interval

3 Downgraded once: size of differences highly variable (I² = 78%; Chi² = 17.95, P value = 0.001), but consistently more adverse effects in drug groups

Background

This review is an update of a previously published review in The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Issue 1, 2009] on acupuncture for migraine (Linde 2009).

Description of the condition

Migraine is a disorder with recurrent headaches manifesting in attacks lasting from four to 72 hours. Typical characteristics of the headache are unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe intensity, aggravation by routine physical activity and association with nausea, photophobia or phonophobia, or any combination of all three (IHS 2013). Epidemiological studies have consistently shown that migraine is a common disorder with a one‐year prevalence of around 10% to 12% and a lifetime prevalence of between 15% and 20% (Oleson 2007). In Europe, the economic cost of migraine is estimated at EUR 27 billion per year (Andlin‐Sobocki 2005). Migraine is subclassified into the more frequent episodic migraine (fewer than 15 days with migrainous headaches per month) and the less frequent chronic migraine (more than 15 days per month). Most people with migraine can be adequately managed by treatingof acute headaches alone, but a relevant minority need prophylactic interventions, as their attacks are either very frequent or are insufficiently controlled by acute therapy. Several drugs, such as propranolol, metoprolol, flunarizine, valproic acid and topiramate, have been shown to reduce attack frequency in some people (Dodick 2007; Linde M 2013a; Linde M 2013b), however, all these drugs are associated with adverse effects. Dropout rates in most clinical trials are high, suggesting that the drugs are not well accepted by patients. There is some evidence that behavioural interventions such as relaxation or biofeedback are beneficial (Holroyd 1990; Nestoriuc 2007), but additional effective, low‐risk treatments are clearly desirable.

Description of the intervention

Acupuncture in the context of this review is defined as the needling of specific points of the body. It is one of the most widely used complementary therapies in many countries (Bodeker 2005). For example, according to a population‐based survey in 2002 in the United States of America (USA), 4.1% of respondents reported lifetime use of acupuncture, and 1.1% reported recent use (Burke 2006). A similar survey in Germany performed in the same year found that 8.7% of adults between 18 and 69 years of age had received acupuncture treatment in the previous 12 months (Härtel 2004). Acupuncture was originally developed as part of Chinese medicine wherein the purpose of treatment was to bring the patient back to the state of equilibrium postulated to exist prior to illness (Endres 2007). Some acupuncture practitioners have dispensed with these concepts and understand acupuncture in terms of conventional neurophysiology. Acupuncture is often used to treat headache, especially migraine. For example, 9.9% of the acupuncture users in the US survey mentioned above stated that they had been treated for migraine or other headaches (Burke 2006).

How the intervention might work

Many studies have shown that acupuncture has short‐term effects on a variety of physiological variables relevant to analgesia (Bäcker 2004; Endres 2007). However, it is unclear to what extent these observations from experimental settings are relevant to the long‐term effects reported by practitioners. It is assumed that a variable combination of local effects; spinal and supraspinal mechanisms; and cortical, psychological or 'placebo' mechanisms contribute to the clinical effects in routine care (Carlsson 2002). While there is little doubt that acupuncture interventions cause neurophysiological changes in the organism, the traditional concepts of acupuncture involving specifically located points on a system of 'channels' called meridians are controversial (Kaptchuk 2002). As for many non‐pharmacological interventions, it is difficult to create sham interventions for acupuncture which are both indistinguishable and physiologically inert. This is due both to technical reasons and the unclear mechanism of action. Consequently, trials using sham acupuncture controls must be interpreted carefully, as sham treatments might not be inactive placebos, while trials comparing acupuncture with no prophylactic treatment, prophylactic drugs or other interventions must also be interpreted carefully, as they have a higher risk of bias due to lack of blinding.

Why it is important to do this review

Despite acupuncture's widespread use its effectiveness is still discussed controversially (Da Silva 2015, McGeeney 2015). Since the publication of the previous version of our Cochrane review (Linde 2009) a number of new trials have been published. Therefore, an update of the review was necessary. To sharpen the focus of our review we narrowed our selection criteria. In particular, we now focus on episodic migraine.

Objectives

To investigate whether acupuncture is a) more effective than no prophylactic treatment/routine care only; b) more effective than 'sham' (placebo) acupuncture; and c) as effective as prophylactic treatment with drugs in reducing headache frequency in patients with episodic migraine.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included controlled trials investigating the prophylactic effect of acupuncture in which allocation to treatment was explicitly randomized, and in which participants were followed up for at least eight weeks after randomisation. We excluded trials in which a clearly inappropriate method of randomisation was used, for example, open alternation.

Types of participants

We included trials in which study participants had been diagnosed with episodic migraine (the word episodic did not have to be mentioned in the report explicitly; see exclusion criteria below to exclude trials focusing on chronic migraine). Studies focusing on migraine but including participants with additional tension‐type headache were included. We included studies including participants with headaches of various types (for example, some participants with migraine, some with tension‐type headache) only if findings for participants with migraine were available separately, or if more than 90% of participants suffered from migraine.

The duration of the condition had to be longer than one year in the great majority (more than 80%) of participants. This criterion was considered met if:

duration for longer than year was an inclusion criterion; or

the mean duration minus one standard deviation was more than one year; or

the mean duration (standard deviation not reported) was more than 10 years; or

other information was presented that made it highly likely that the criterion was met (e.g. study authors presented proportions with duration ranges).

We excluded trials in patients with chronic migraine, chronic daily headache or in which at baseline more than half of participants had more than 15 days with migrainous headache per month. We also excluded trials in which there was no information of the duration of headache complaints.

Changes to previous version

In this update of the review we have excluded trials focusing on chronic migraine, as the definition of chronic migraine is still debated and the separation from other diagnoses, for example headache due to medication overuse, is difficult (in the previous version of this review (Linde 2009) we were not aware of any trials on chronic migraine and they were not explicitly excluded). In the current update we have also excluded trials in which a relevant proportion of participants had been suffering from migraine for less than one year or in which duration was unclear.

Types of interventions

Experimental interventions

Any treatment involving needle insertion (with or without manual or electrical stimulation) at acupuncture points, pain points or trigger points, described as acupuncture. The planned treatment course must have had at least six treatment sessions, and been given at least once per week. Trials with individualised strategies were included if the median or mean number of treatments was at least six sessions, and there was no reason to believe that treatments were given less frequently than once per week in the majority of participants.

-

We excluded studies that:

exclusively investigated acupuncture at specific ‘micro‐systems’ (e.g. scalp or ear acupuncture), although we included trials using micro‐system points in addition to body acupuncture;

investigated other methods of stimulating acupuncture points without needle insertion, for example, acupressure, laser stimulation or transcutaneous electrical stimulation;

injected fluids at acupuncture or trigger points.

Control interventions

No treatment other than treatment of acute migraine attacks or routine care (which typically includes treatment of acute attacks, but might also include other treatments; however, trials normally require that no new experimental or standardized treatment be initiated during the trial period).

Sham interventions (interventions mimicking 'true' acupuncture/true treatment, but deviating in at least one aspect considered important by acupuncture theory, such as skin penetration or correct point location).

Prophylactic pharmacological treatment (for example, β‐blocking agents, calcium channel antagonists, anti‐epileptic drugs) given for at least eight weeks.

We excluded trials comparing acupuncture to food supplements, herbal drugs or combinations of herbal drugs, and trials that only compared different forms of acupuncture.

Changes to previous version

In the previous version of the review (Linde 2009) we included trials using any prophylactic treatment other than acupuncture as comparison. With a slowly increasing number of trials using a wide range of different treatments (mainly various herbal medicines) we decided to concentrate on conventional prophylactic pharmacological treatment to keep the review focused. We have defined a minimum number and frequency of acupuncture treatment sessions to ensure that treatments meet basic quality criteria.

Types of outcome measures

We included studies if they measured at least one of the following outcome measures for at least eight weeks after randomisation:

headache frequency (attacks, days, hours, headache‐free days) per defined time period;

response (≥ 50% frequency reduction documented in a headache diary);

disability or quality of life with a validated measure.

We excluded trials that:

focussed on the treatment and measurement of acute attacks;

reported only measures such as “total effectiveness rate” (e.g. proportion of participants healed, much improved, improved, unchanged);

reported only physiological or laboratory parameters;

had outcome measurement periods of less than eight weeks (from randomisation to final observation).

Changes to previous version

We have defined outcome measures more precisely to ensure that measurement methods meet current standards of migraine research.

Primary outcomes

The primary efficacy outcome of our systematic review was headache frequency at completion of treatment and at follow‐up. The primary safety/acceptability outcomes were the number of participants dropping out due to adverse effects and the number of participants reporting at least one adverse event or effect (see Measures of treatment effect for details).

Secondary outcomes

The secondary efficacy outcome of our systematic review was the proportion of 'responders' at completion of treatment and at follow‐up.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this update we searched the following databases without language restrictions (date of the last search 20 January 2016):

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; The Cochrane Library 2016, Issue 1), searched from 2008 to 2016;

MEDLINE (via Ovid) 2008 to week 1 of January 2016;

EMBASE (via Ovid) 2008 to 19 January 2016;

AMED (via OVID) 1985 to January 2016.

The search strategies are reported in Appendix 1. In addition, the first author checked PubMed monthly for new publications, screening all hits for 'acupuncture AND (headache OR migraine)' (last search 12 April 2016). For previous versions of this review (Melchart 2001; Linde 2009) we had searched the Cochrane Complementary Medicine Field Trials Register (whose results are now included in CENTRAL without relevant delay) and the Cochrane Pain, Palliative & Supportive Care Trials Register (no longer updated).

Searching other resources

We searched the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; apps.who.int/trialsearch/) and ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov) for completed or ongoing trials using the search string 'acupuncture AND (headache OR migraine)'. The last search was on February 10, 2016. We also searched the reference lists of all eligible studies for additional studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors screened all abstracts identified by the updated search and excluded those that were clearly irrelevant (for example, studies focusing on other conditions, reviews, etc.). We obtained full texts of all remaining references and, again, screened them to exclude clearly irrelevant papers. At least two review authors formally checked all remaining articles and all trials included in the previous version of our review (Linde 2009) for eligibility according to the above‐mentioned selection criteria. We resolved any disagreements by discussion.

Data extraction and management

At least two review authors independently extracted information on participants, methods, interventions, outcomes and results using a specially designed form before entry into Review Manager (RevMan) (RevMan 2014). In particular, we extracted exact diagnoses; headache classifications used; number and type of centres; age; sex; duration of disease; number of participants randomized, treated and analysed; number of, and reasons for dropouts; duration of baseline, treatment and follow‐up periods; details of acupuncture treatments (such as selection of points; number, frequency and duration of sessions; achievement of de‐chi (an irradiating feeling considered to indicate effective needling); number, training and experience of acupuncturists); and details of control interventions (sham technique, type and dosage of drugs). For details regarding methodological issues and study results, see below.

Where necessary, we sought additional information from the first or corresponding authors of the included studies.

For six trials (Diener 2006; Jena 2008; Li 2012; Linde K 2005; Streng 2006; Vickers 2004) included in the individual patient database of the Acupuncture Trialists' Collaboration (ATC), an international collaborative network for high quality randomized trials of acupuncture for chronic pain (see Vickers 2010; Vickers 2012), we obtained uniformly re‐analysed summary data for numeric variables and the number of responders for calculation of effect sizes. We used these data to ensure that we obtained the most precise estimate of treatment effect. For each trial, we created an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model for each numeric outcome at each time point and adjusted for the baseline value of that outcome, treatment group (acupuncture or control), and any variables that were used to stratify randomisation in the original trial. Using this model, we calculated the adjusted mean outcome values for each group (acupuncture and control), and we used the standard error for the effect of treatment from the ANCOVA model to calculate the standard deviation for the difference in adjusted means. Therefore, effect sizes calculated in our analyses might to some degree deviate from those in the original publications of the six trials. Use of raw data also allowed us to calculate response rates, such as for a 50% reduction in pain, even if this was not reported in the original trial publication.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For the assessment of study quality, the risk of bias approach for Cochrane reviews was used (Higgins 2011). We used the following six separate criteria:

adequate sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding;

incomplete outcome data addressed (up to three months after randomisation);

incomplete follow‐up outcome data addressed (four to 12 months after randomisation);

free of selective reporting.

We did not include the item 'other potential threats to validity' in a formal manner, but noted if relevant flaws were detected.

In a first step, we copied information relevant to making a judgment on a criterion from the original publication into an assessment table. We entered any additional information from the study authors into the table, if it was available, , along with an indication that this was unpublished information. At least two reviewers independently made a judgment on whether the risk of bias for each criterion was considered low, high or unclear. We resolved any disagreements by discussion.

For the first five criteria (above), we followed the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). For 'selective reporting', we decided to use a more liberal definition. Headache trials typically measure a multiplicity of headache outcomes at several time points using diaries, and there is a plethora of slightly different outcome measurement methods. While a single primary endpoint is sometimes predefined, the overall pattern of a variety of outcomes is necessary to get a clinically interpretable picture. If we had applied the strict guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, almost all trials would have been rated 'unclear' for 'selective reporting'. We considered trials as having a low risk of bias for selective reporting if they reported the results of the most relevant headache outcomes assessed (typically a frequency measure, intensity, analgesic use and response) for the most relevant time points (end of treatment and, if done, follow‐up), and if the outcomes and time points reported made it unlikely that study investigators had picked them out because they were particularly favourable or unfavourable.

If trials had both blinded sham control groups and unblinded comparison groups receiving no prophylactic treatment or drug treatment, in the risk of bias tables, the 'Judgement' column always relates to the comparison with sham interventions. In the 'Description' column, we included the assessment for the other comparison group(s). As the risk of bias table does not include a 'not applicable' option, we rated the item 'incomplete follow‐up outcome data addressed (four to 12 months after randomisation)?' as 'unclear' for trials that did not follow participants longer than three months.

We also assessed the adequacy of concealment of allocation according to the criteria of the ATC (Vickers 2010) which are stricter than those in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. In particular, in the case of envelope randomisation, investigators must have established and described detailed procedures to ensure that allocation could neither be predicted nor changed post hoc. For example, there should have been procedures to prevent investigators resealing and reusing an envelope after it had been opened (e.g. envelopes were held by an independent party). As the level of information needed for this assessment was often not available in publications, we contacted study authors for clarification. If information was not available, we did not consider adequacy of concealment to be "unambiguously adequate".

Assessment of the adequacy of the acupuncture intervention

We also attempted to provide a crude estimate of the quality of acupuncture. At least two reviewers who are trained in acupuncture and have several years of practical experience (GA, BB, YF, AW) answered two questions. First, they were asked how they would treat the participants included in the study. Answer options were 'exactly or almost exactly the same way', 'similarly', 'differently', 'completely differently' or 'could not assess' due to insufficient information (on acupuncture or on the participants). Second, they were asked to rate their degree of confidence that acupuncture was applied in an appropriate manner on a 100‐mm visual scale (with 0% = complete absence of evidence that the acupuncture was appropriate, and 100% = total certainty that the acupuncture was appropriate). A member of the review team (AW) proposed the latter method , which was used in a systematic review of clinical trials of acupuncture for back pain (Ernst 1998). In the Characteristics of included studies table, the acupuncturists' assessments are summarized under 'Methods' (for example, "similarly/70%" indicates a trial where the acupuncturist‐reviewer would treat 'similarly' and is '70%' confident that acupuncture was applied appropriately).

Measures of treatment effect

Main analysis

Our primary efficacy outcome was headache frequency at completion of treatment and at follow‐up (closest to six months after randomisation). As studies may report either attacks, migraine days or headache days as a measure of headache frequency, we used a system where various frequency measures could be used. As available, we used (in descending order of preference) absolute values from four‐week periods or other periods for (again, in descending order of preference) migraine days, migraine attacks or headache days. Due to the variability of outcomes, standardized mean differences (SMD) were calculated as effect size measures. Negative values indicate better outcomes in the acupuncture group.

Our secondary efficacy outcome was the proportion of 'responders' at completion of treatment and at follow‐up (closest to six months after randomisation). Response was defined as a reduction in migraine days of at least 50% compared to baseline. If the number of responders regarding migraine days was not available we used at least 50% reduction in number of migraine attacks (second preference), or at least 50% reduction in number of headache days (third preference). We calculated risk ratios (RR) of having a response and 95% confidence intervals (CI) as effect size measures. Risk ratios greater than 1 indicate that there were more responders in the acupuncture group compared to the comparator group. When reporting results on response in this review (in the abstract, the plain language summary, the results section and the 'Summary of findings' tables) these are based on the observed proportion (sum of participants with response divided by the sum of participants randomized) in the control group and the expected proportion based on the pooled risk ratio from meta‐analysis.

As primary safety/acceptability outcomes we used the number of participants dropping out due to adverse effects and the number of participants reporting at least one adverse event or effect. Further safety/acceptability outcomes were the number of participants not reaching the primary endpoint (we originally had planned to extract the number of participants dropping out but this proved difficult due to multiple measurement time points and reporting issues) and the number of participants with serious adverse events. As the number of events was typically low we calculated odds ratios (OR) instead of risk ratios. Odds ratios greater than 1 indicate more events (e.g. dropouts) in the acupuncture group.

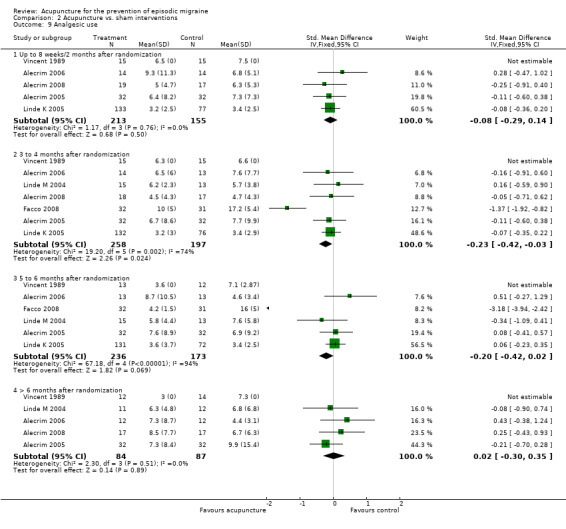

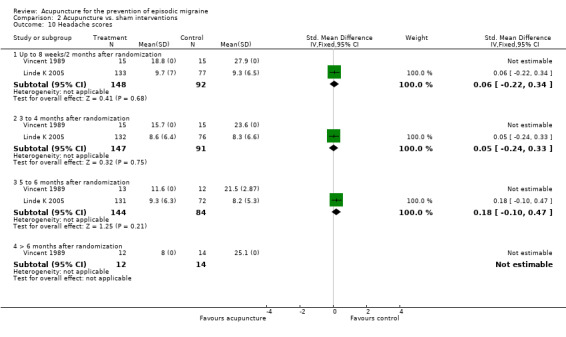

Time window analysis

In the previous version of this review (Linde 2009) we analysed findings according to the four time windows described below. This had the advantage that measurement times used were similar across trials. However, it had two disadvantages. Firstly, duration of treatment periods was quite variable, so while in some trials treatment was already completed (e.g. at 8 weeks) it was still ongoing (e.g. until week 16) in others; secondly, four time windows for each outcome made the 'Summary of findings' tables very complex. Therefore, in this update we have reported the time window analyses as additional analyses only.

We used the following time windows:

up to eight weeks/two months after randomisation;

three to four months after randomisation;

five to six months after randomisation; and

more than six months after randomisation.

If more than one data point was available for a given time window, we used: for the first time window, preferably data closest to eight weeks; for the second window, data closest to the four weeks after completion of treatment (for example, if treatment lasted eight weeks, data for weeks nine to 12); for the third window, data closest to six months; and for the fourth window, data closest to 12 months.

The following outcomes were used in the time windows analysis.

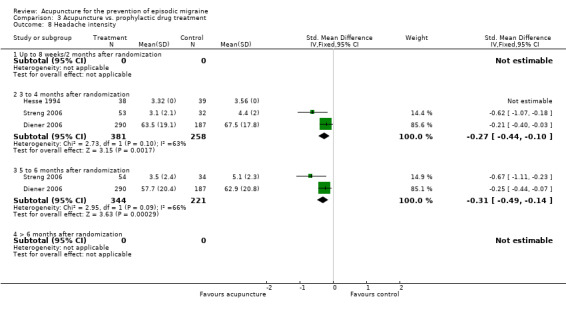

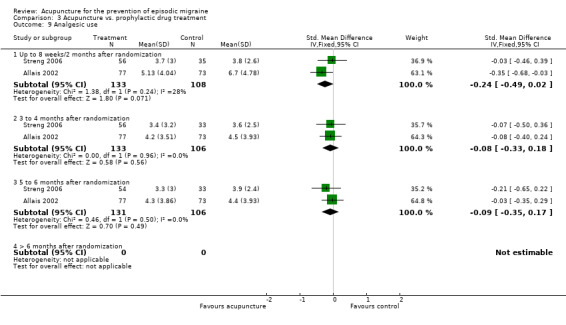

Frequency of migraine attacks (means and standard deviations) per four‐week period. Mean differences were calculated as effect size measures

Response (risk ratio of having a response).

Number of migraine days (means and standard deviations) per four‐week period (mean differences).

Number of headache days (means and standard deviations) per four‐week period (mean differences).

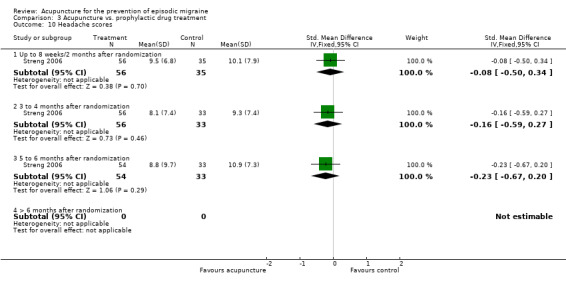

Headache intensity (any measures available, extraction of means and standard deviations, calculation of SMDs).

Frequency of analgesic use (any continuous or rank measures available, extraction of means and standard deviations, calculation of SMDs).

Headache scores (SMDs)

All these outcomes rely on participant reports, mainly collected in headache diaries.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual participant.

Dealing with missing data

If publications reported study findings with insufficient detail or in an inconsistent manner we attempted to obtain further information from the study authors.

Regarding missing participant data due to dropout or loss to follow‐up in the included studies we used the following strategies.

-

Efficacy outcomes:

for comparisons of acupuncture with no acupuncture and sham we used for continuous measures, if available, the data from intention‐to‐treat analyses with missing values replaced; otherwise, we used the presented data on available cases;

for response we used the number of responders divided by the number of participants randomized to the respective group (counting missing information as non‐response). In studies comparing acupuncture with drug treatment, we used as first preference analyses of participants having at least started treatment as first preference, available cases as second preference and intention‐to‐treat analyses as third preference.

-

Safety outcomes:

for all comparisons we used the number of participants randomized as denominator for the outcomes number of participants dropping out due to adverse effects, not reaching the primary endpoint and experiencing serious adverse events;

for the outcome number of participants reporting adverse effects we used the number of participants having received at least one treatment as denominator.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity with the Chi² test (Deeks 2011) and the I² statistic (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

In forest plots studies are ordered according to their weight in meta‐analysis. The weight depends on the standard errors of the point estimate (precision) which is dependent on sample size and variability/frequency of events. This gives readers a crude impression whether more and less precise trials yield similar findings.

Data synthesis

For the purposes of summarizing results, we categorized the included trials according to control groups:

comparisons with no acupuncture (acute treatment only or routine care);

comparisons with sham acupuncture interventions;

comparisons with prophylactic drug treatment.

If a trial included more than one acupuncture group, we pooled results of the groups so that participants in the control group were counted more than once.

We calculated pooled fixed‐effect estimates, their 95% confidence intervals, the Chi2 test for heterogeneity and the I2 statistic. If the P value of the Chi² test for heterogeneity was less than 0.2 or I² greater than 40%, or both, we also reported random‐effects estimates.

Change to previous version

Based on the recommendation of the statistician in our team (AV) we have used fixed‐effect models for calculating pooled estimates in this updated review. This is primarily because the fixed‐effect analysis constitutes a valid test of the null hypothesis. Moreover, due to very large discrepancies in sample size, a random‐effects model would have resulted in participants in small studies being given greater weight that participants in large studies. . Nonetheless, if the P value of the Chi² test for heterogeneity was less than 0.2 or I² was greater than 40%, or both, we have also reported random‐effect estimates.

We used the GRADE approach to assess the quality of evidence related to each of the key outcomes as appropriate (GRADEpro GDT 2015; Schünemann 2011). GRADE Working Group grades of evidence are:

High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate, the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited, the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate, the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

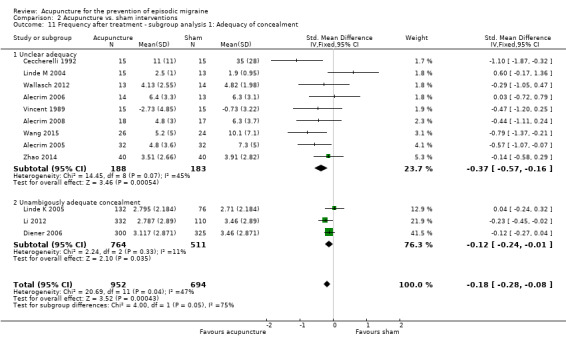

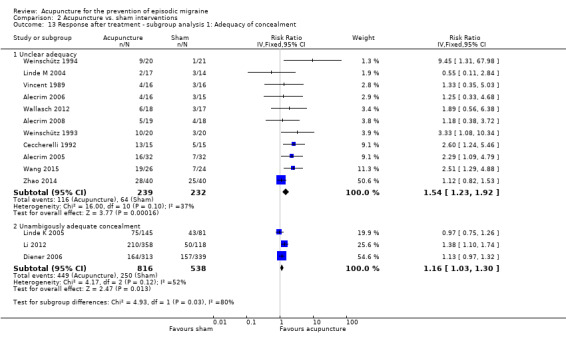

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

To investigate potential sources of heterogeneity and the robustness of our findings we performed subgroup analyses for the primary outcome, headache frequency, and for the secondary outcome, response, both after treatment and at follow‐up for the comparison vs. sham (the number of trials being too small for the other two comparisons) for four variables. These variables were selected after reviewing the trials qualitatively but before running analyses: unambiguously adequate randomisation vs. other; larger (sample size above median of the trials included in the analysis) vs. smaller trials; number of treatment sessions up to 12 vs. 16 and more; and sham penetrating the skin vs. non‐penetrating sham.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Update searches identified 528 hits (518 by database searches, six by checking references and alerts, and four from checking entries in trials registries not identified otherwise). Thirty‐six full‐text publications and four entries in clinical trial registries that were deemed potentially eligible were formally checked against the eligibility criteria (see Figure 1). As we had modified selection criteria for this update, we reassessed the 22 trials included in the previous version for eligibility. Five new trials met the revised selection criteria (Facco 2013; Li 2012; Wallasch 2012; Wang 2015; Zhao 2014), while five trials included in the previous version or our review had to be excluded (Baust 1978; Doerr‐Proske 1985; Dowson 1985; Henry 1985; Wylie 1997; see Characteristics of excluded studies).

1.

Flow diagram

Included studies

General characteristics

Twenty‐two trials including 4985 participants in total (median 71, range 30 to 1715) met our selection criteria; 18 studies were two‐armed, two were three‐armed and a further two were four‐armed (see Characteristics of included studies). All trials used parallel‐group designs; there were no cross‐over studies. Fifteen trials included a sham acupuncture control group (Alecrim 2005; Alecrim 2006; Alecrim 2008; Ceccherelli 1992; Diener 2006; Facco 2008; Li 2012; Linde K 2005; Linde M 2004; Vincent 1989; Wallasch 2012; Wang 2015; Weinschütz 1993; Weinschütz 1994; Zhao 2014), five a no‐acupuncture control group (Facco 2008; Jena 2008; Linde K 2005; Linde M 2000; Vickers 2004), and five a comparator group receiving prophylactic drug treatment (Allais 2002; Diener 2006; Facco 2013; Hesse 1994; Streng 2006). Sixteen trials were performed in a single centre and six were multicentre trials. Seven trials were performed in Germany, four in Italy, three in Brazil, two each in China, Sweden and the UK, and one each in Denmark and Australia. Seven trials were published between 1989 and 2002 and 15 between 2004 and 2015. We tried to contact corresponding authors of all trials at least once (either for previous versions of this review or for the current update). For one trial we could not obtain a valid contact address (Hesse 1994) and three study authors or co‐authors did not provide additional information before completion of this update (Wallasch 2012; Weinschütz 1993; Weinschütz 1994). For the remaining 18 trials we obtained some additional information. Detailed additional data for effect size calculation was obtained from study authors or from the individual patient database of the ATC for 11 trials (Alecrim 2005; Alecrim 2006; Alecrim 2008; Allais 2002; Diener 2006; Jena 2008; Li 2012; Linde K 2005; Streng 2006; Vickers 2004; Vincent 1989).

Study participants

Fifteen trials included participants diagnosed as having migraine with or without aura, six exclusively participants without aura, and one recruited only women with menstrually‐related migraine (Linde M 2004). In two large, pragmatic multicentre trials (Jena 2008; Vickers 2004) baseline headache frequency and the reported diagnoses make it likely that, in spite of the use of the criteria of the International Headache Society, there was some diagnostic misclassification (i.e. some participants were likely to suffer from tension‐type headache and not migraine). This applied to a minor extent also to three other multicenter trials (Diener 2006; Linde K 2005; Streng 2006).

Acupuncture interventions

The acupuncture interventions tested in the included trials varied to a great extent. Five trials (Allais 2002; Ceccherelli 1992; Li 2012; Wallasch 2012; Zhao 2014 ) standardized acupuncture treatments (all participants were treated at the same points); seven (Alecrim 2006; Diener 2006; Facco 2013; Linde K 2005; Linde M 2000; Linde M 2004; Wang 2015) semi‐standardized treatments (either all participants were treated at some basic points and additional individualized points, or there were different predefined needling schemes depending on symptom patterns); and 10 trials individualized the selection of acupuncture points (Alecrim 2005; Alecrim 2008; Facco 2008; Hesse 1994; Jena 2008; Streng 2006; Vickers 2004; Vincent 1989; Weinschütz 1993; Weinschütz 1994). The number of treatment sessions was between six and 12 in 13 trials, and 16 or more in nine trials. Most trials reporting the duration of sessions, left needles in place for between 20 and 30 minutes; one trial (Hesse 1994) investigated brief needling for a few seconds. Electro‐stimulation of needles was used in one trial (Li 2012). Agreement among acupuncturists on whether they would do acupuncture similarly to that used in the study assessed and whether they had confidence in the quality of the acupuncture was low (intra‐class correlation coefficients ‐0.08 and 0.24). For two studies (Hesse 1994; Linde M 2004) both acupuncturists rating the study had 50% or less confidence that the acupuncture had adequate quality. For a further six studies (Ceccherelli 1992; Li 2012; Linde M 2000; Wallasch 2012; Weinschütz 1993; Weinschütz 1994) at least one acupuncturist gave a rating of 50% or lower. We could not assess four trials using individualized treatments not described in detail (Alecrim 2005; Alecrim 2008; Facco 2008; Jena 2008).

Comparator interventions

Five trials included a group which either received treatment of acute attacks only (Facco 2008; Linde K 2005; Linde M 2000) or 'routine care' that was not specified by protocol (Jena 2008; Vickers 2004), while the experimental group received acupuncture in addition. In the 15 trials with a sham control, techniques varied considerably. Four trials superficially needled recognized acupuncture points considered inadequate for the treatment of migraine (Alecrim 2005; Alecrim 2006; Alecrim 2008; Zhao 2014); seven trials used needling (mostly superficial) of non‐acupuncture points at variable distance from true points (Diener 2006; Li 2012; Linde K 2005; Vincent 1989; Wallasch 2012; Weinschütz 1993; Weinschütz 1994). Two trials (Facco 2008; Linde M 2004) used 'placebo' needles (telescopic needles with blunt tips not penetrating the skin). In Linde M 2004 these were placed at the same predefined points as in the true treatment group. Facco 2008 had two sham groups: in one group the placebo needles were placed at correct, individualized points after the same process of Chinese diagnosis as in the true treatment group. In the second group placebo needles were placed at standardized points without the 'Chinese ritual' (to investigate whether the different interaction and process affected outcomes). One study (Ceccherelli 1992) used a complex procedure without real needling. One study used a mix of superficial needling at non‐acupuncture points and a non‐penetrating technique (with a blunted cocktail stick) for points on the head (Wang 2015). Five trials compared acupuncture to prophylactic drug treatment, using metoprolol (Hesse 1994; Streng 2006), flunarizine (Allais 2002), valproic acid (Facco 2013) or individualized treatment according to guidelines (Diener 2006). In four of these trials participants were unblinded, while one blinded trial used a double‐dummy approach (true acupuncture + metoprolol placebo vs. metoprolol + sham acupuncture; Hesse 1994).

Excluded studies

Results were not yet available for eight studies registered in trial registries likely to meet selection criteria. For four of these, detailed protocols have been published (Chen 2013; Lan 2013; Vas 2008; Zhang 2013); for the other four only the registry entries were available (Li 2007; Liang 2013; Wang J 2015; Xing 2015). For at least four trials recruitment has been completed (Lan 2013; Li 2007; Vas 2008; Wang J 2015) (see Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Twenty studies (described in 23 publications) did not meet selection criteria (Agro 2005; Boutouyrie 2010; Ceccherelli 2012; Deng 2006; Ferro 2012; Foroughipour 2014; Han 2011; Jia 2009; Matra 2012; Qin 2006; Vijayalakshmi 2014; Wang 2011; Wu 2011; Yang 2009; Yang 2011; Zhang 2006; Zhang 2009; Zheng 2013; Zhong 2009; Zhou 2007). A number of Chinese trials were excluded due to inadequate duration of prophylactic drug treatment (several Chinese trials gave flunarizine or other drugs for four weeks only), overall observation of less than eight weeks, inclusion of participants with recent onset of migraine, and lack of relevant outcome measures. Furthermore, five trials included in the previous version of our review were excluded (Baust 1978; Doerr‐Proske 1985; Dowson 1985; Henry 1985; Wylie 1997). Reasons for exclusions are reported in the Characteristics of excluded studies.

Studies awaiting classification

We classified three trials (five publications) identified by our most recent update search as awaiting assessment (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). One (Giannini 2015) is an abstract of an interim analysis of a trial comparing acupuncture and individualized prophylactic drug treatment. The abstract does not provide sufficient information but based on background information available to one of us (KL) it seems likely that the trial will meet our eligibility criteria when a full publication with final data becomes available. A second trial originating from China (Li 2016) was published in February and April 2016 after all analyses for this review had been completed. The two publications focus on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) outcomes but also report headache frequency data for participants completing all fMRI measurements. It seems likely that these trials will meet inclusion criteria. A third trial of uncertain eligibility (participants with "menstrual headache") is available only in Chinese (Sun 2015). Full text translation has to be available before final assessment of eligibility.

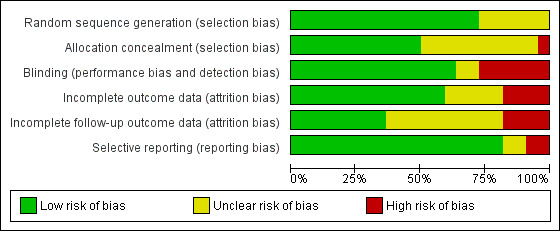

Risk of bias in included studies

We discuss the methodological quality of trials (risk of bias) for the three comparisons separately, as problems differ according to control groups. The risk of bias assessments of single trials are displayed in Figure 2; a summary across trials is presented in Figure 3. It should be noted that three trials rated unclear for the item 'incomplete follow‐up outcome data' actually did not include a follow‐up (Ceccherelli 1992; Jena 2008; Zhao 2014).

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study. Note: for trials including both a comparison with sham and a no‐acupuncture control/prophylactic drugs (Diener 2006, Facco 2008, Linde K 2005) blinding was assessed for the comparisons with sham. For the comparisons with no acupuncture/prophylactic drugs the risk of bias is high (no blinding).

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

Comparisons with no acupuncture (acute treatment only or routine care)

Four trials (Facco 2008; Jena 2008; Linde K 2005; Vickers 2004) used adequate methods for allocation sequence generation and concealment of allocation when judged according to the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011). According to the definition of the ATC, three trials (Jena 2008; Linde K 2005; Vickers 2004) were "unambiguously adequately concealed". For the two other trials sequence generation was adequate but concealment was inadequate (Linde M 2000) or not fully adequate (Facco 2008). Given the comparison between acupuncture and no acupuncture, the participants (who were also assessing all relevant outcomes) were unblinded in all six trials. In consequence, bias could not be ruled out. The use of headache diaries to monitor symptoms closely over a long period of time (Linde K 2005; Linde M 2000; Vickers 2004) might be less prone to bias than the use of questionnaires with retrospective assessment of symptoms for the preceding weeks (Facco 2008; Jena 2008). Attrition in the first three months was high in Linde M 2000 and minor to moderate in the remaining trials. The analyses of Jena 2008, Linde K 2005 and Vickers 2004 took account of attrition, suggesting a low risk of bias. This also applied to the long‐term follow‐up in Vickers 2004. Facco 2008 presented only a per‐protocol analysis. Although presentation of results was not always optimal, we considered the risk of selective reporting to be low as the most important outcome measures were always presented and consistent. Overall, due to the lack of blinding in all studies there was some risk of performance and detection bias for this comparison.

Comparisons with sham interventions

We could not formally assess the quality of Alecrim 2005, for which only an abstract and additional unpublished information provided by the authors were available. Unpublished information provided by the authors and published information from the two other trials (Alecrim 2006; Alecrim 2008) conducted by the same group suggested that the risk of bias in this trial was low. Among the 13 trials formally assessed, the risk of bias regarding sequence generation was low for 10 (Alecrim 2006; Alecrim 2008; Ceccherelli 1992; Diener 2006; Facco 2008; Li 2012; Linde K 2005; Linde M 2004; Wang 2015; Zhao 2014) and unclear in five. Publications for five trials reported adequate methods of allocation concealment (Alecrim 2006; Alecrim 2008; Diener 2006; Li 2012; Linde K 2005); for a further two trials, such information was provided by the authors (Ceccherelli 1992; Facco 2008). All the trials attempted to blind participants. Several trials that used sham interventions which were not strictly indistinguishable from 'true' acupuncture (Ceccherelli 1992; Diener 2006; Facco 2008; Linde K 2005) did not mention explicitly the use of a sham or placebo control in the informed consent procedure. This is ethically problematic, but enhances the credibility of the sham interventions. Taking into account also the results of the trials, we considered the risk of bias to be low in all trials. Reporting of dropouts was insufficient in several older trials. We considered the risk of bias to be low regarding short‐term outcomes (up to three months) in nine trials (Alecrim 2006; Alecrim 2008; Diener 2006; Li 2012; Linde K 2005; Linde M 2004; Vincent 1989; Wang 2015; Zhao 2014), and low regarding long‐term outcomes in six (Alecrim 2008; Diener 2006; Li 2012; Linde K 2005; Linde M 2004; Wang 2015). For two trials (Weinschütz 1993; Weinschütz 1994) outcomes were reported so inadequately that selective reporting could not be ruled out. Overall, the risk of bias was variable, but, particularly in the three largest trials, good quality. However, as acupuncturists could not be blinded in any trial performance, bias could not be ruled out completely.

Comparisons with prophylactic drug treatment

Three trials (Allais 2002; Diener 2006; Streng 2006) used adequate methods for sequence generation and concealment, one trial reported an adequate method for sequence generation but insufficient detail regarding concealment (Facco 2013), and one trial (Hesse 1994) did not describe the methods. Four trials (Allais 2002; Diener 2006; Facco 2013; Streng 2006) compared acupuncture and drug treatment in an open manner, which implies that bias on this level is possible. The use of a double‐dummy technique allowed participant blinding in Hesse 1994, but this approach might be associated with other problems (see Discussion). While there is little risk of bias due to low attrition rates in Allais 2002 and Hesse 1994, and unclear risk in Facco 2013, a relevant problem occurred in the two German trials (Diener 2006; Streng 2006). The recruitment situation for these trials made it likely that participants had a preference for acupuncture. This resulted in a high proportion of participants allocated to drug treatment withdrawing informed consent immediately after randomisation (34% in Diener 2006 and 13% in Streng 2006), as well as high treatment discontinuation (18% in Diener 2006) or dropout rates due to adverse effects (16% in Streng 2006). These trials did not include participants refusing informed consent immediately after randomisation in analyses, and one (Streng 2006) also excluded early dropouts. Such analyses should normally tend to favour drug treatment. Both trials presented additional analyses restricted to participants complying with the protocol. All five trials presented the most important outcomes measured, so we considered the risk of bias of selective reporting to be low. Overall, as four of the trials were not blinded and two trials had a problem with relevant attrition in the drug group there is a considerable risk of bias (see also Discussion).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Comparisons with no acupuncture (acute treatment only or routine care)

The five trials comparing acupuncture with a control group receiving either treatment of acute migraine attacks only or routine care are clinically very heterogeneous. Facco 2008 performed a four‐armed trial (n = 160) in which participants in the control group all received acute treatment of attacks with rizatriptan. Jena 2008 is a very large, highly pragmatic study which included a total of 15,056 headache sufferers recruited by more than 4000 physicians in Germany. A total of 11,874 people not giving consent to randomisation received up to 15 acupuncture treatments within three months and were followed for an additional three months. This was also the case for 1613 participants randomized to immediate acupuncture, while the remaining 1569 participants remained on routine care (not further defined) for three months and then received acupuncture. The published analysis of this trial is on all randomized participants, but we received unpublished results of subgroup analyses on the 1715 participants with migraine from the study authors for the previous version of our review and we re‐analysed the data from the ATC for this update. Linde M 2000 was a small pilot trial (n = 39) performed in a specialized migraine clinic in Sweden in which control participants continued with their individualized treatment of acute attacks but did not receive additional acupuncture. A similar approach was used for the waiting‐list control group in the three‐armed (also sham control group) Linde K 2005 (n = 302) trial. Finally, in the Vickers 2004 trial (n = 401), acupuncture in addition to routine care in the British National Health Service was compared to a strategy, 'avoid acupuncture'. In addition to the strong clinical heterogeneity, the methods and timing of outcome measurement in these trials also differed considerably.

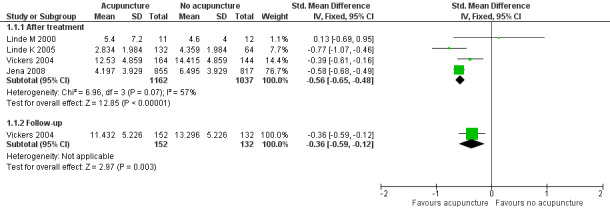

Therefore, pooled effect size estimates have to be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, the findings show that acupuncture treatment is associated with a moderately large short‐term benefit compared to no acupuncture control groups (Figure 4; Figure 5).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Acupuncture vs. no acupuncture, outcome: 1.1 Headache frequency

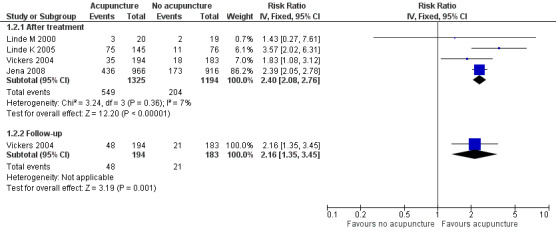

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Acupuncture vs. no acupuncture, outcome: 1.2 Response (at least 50% frequency reduction)

Among the four trials providing sufficient data the pooled fixed‐effects standardized mean difference (SMD) was ‐0.56 (95% CI ‐0.65 to ‐0.48; 2199 participants); findings were statistically heterogeneous (P value = 0.07; I² = 57%; random‐effects estimate ‐0.53; 95% CI ‐0.72 to ‐0.34).

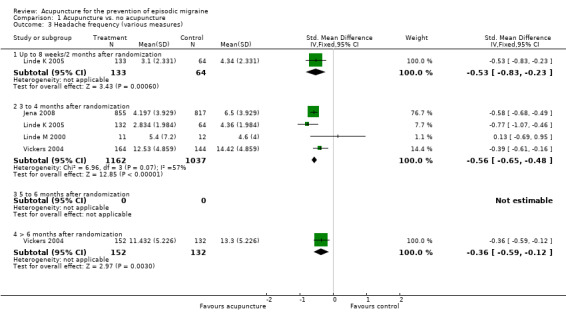

After treatment, headache frequency at least halved in 41% of participants receiving acupuncture and 17% receiving no acupuncture. The fixed effects risk ratio (RR) was 2.40 (95% CI 2.08 to 2.76; 4 trials, 2519 participants); there was no indication of statistical heterogeneity (P value = 0.36; I² = 7%). We consider these findings after treatment as moderate quality evidence because as the large trials consistently show clinically relevant differences, in spite of the risk of bias due to lack of blinding, we found some indication of heterogeneity (headache frequency) and clinical differences between trials. The corresponding number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) was 4 (95% CI 3 to 6). There was only one trial with a follow‐up beyond three months (Vickers 2004; 12 month follow‐up). The SMD (frequency) was ‐0.36 (95% CI ‐0.59 to ‐0.12; 284 participants with data) and the RR for response was 2.16 (95% CI 1.35 to 3.45; 377 participants). The NNTB based on this trial was 7 (95% CI 4.00 to 25.00; proportion of participants with response in the sham group 11%). Although the trial was large we consider its long‐term findings to be low quality evidence as, given the variable effect sizes after treatment in the available trials, future trials performed in different settings might well yield different effect sizes. Findings in the time window analyses are consistent with those of the main analysis (Analysis 1.3; Analysis 1.4). The single specific frequency outcomes, migraine attacks, migraine days and headache days were not measured or reported in any trials but findings were consistent with those in our primary outcome, headache frequency (Analysis 1.5; Analysis 1.6; Analysis 1.7). This also applies to the outcomes headache intensity, analgesic use and headache scores (Analysis 1.8; Analysis 1.9; Analysis 1.10). We did not explore reasons for heterogeneity due to the small number of trials.

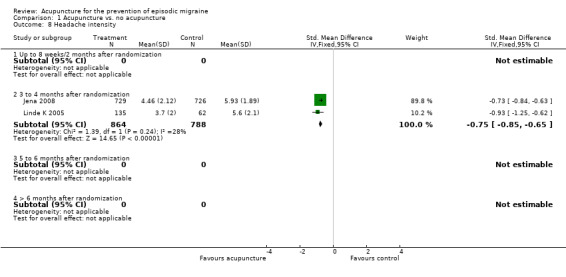

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture vs. no acupuncture, Outcome 3 Headache frequency (various measures).

1.4. Analysis.

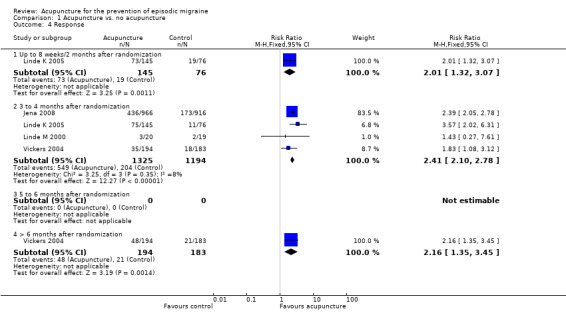

Comparison 1 Acupuncture vs. no acupuncture, Outcome 4 Response.

1.5. Analysis.

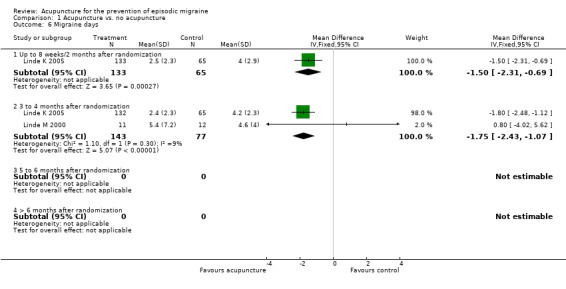

Comparison 1 Acupuncture vs. no acupuncture, Outcome 5 Migraine attacks.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture vs. no acupuncture, Outcome 6 Migraine days.

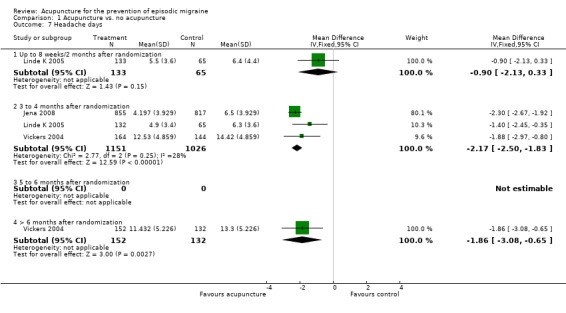

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture vs. no acupuncture, Outcome 7 Headache days.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture vs. no acupuncture, Outcome 8 Headache intensity.

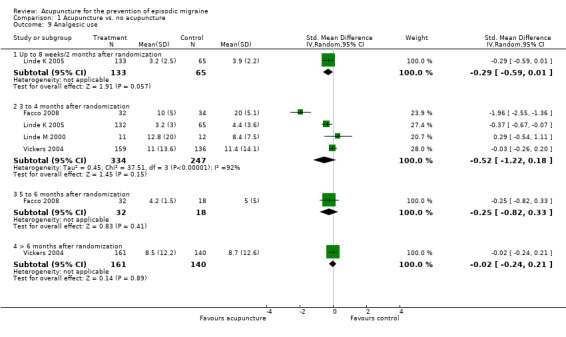

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture vs. no acupuncture, Outcome 9 Analgesic use.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture vs. no acupuncture, Outcome 10 Headache scores.

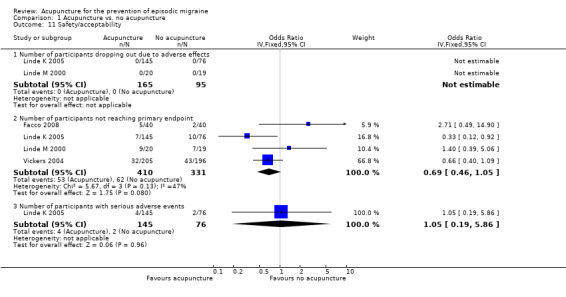

The number of participants not reaching the primary endpoint was slightly lower in acupuncture than in non‐acupuncture groups (OR 0.69; 95% CI 0.46 to 1.05); there was some heterogeneity (P value = 0.13; I² = 47%). In the two trials reporting reasons for attrition there were no dropouts due to adverse effects. Information on other safety/acceptability outcomes was reported insufficiently (see Analysis 1.11).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture vs. no acupuncture, Outcome 11 Safety/acceptability.

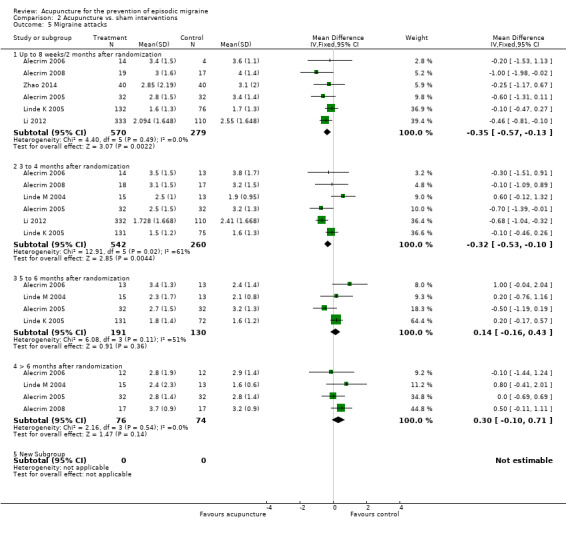

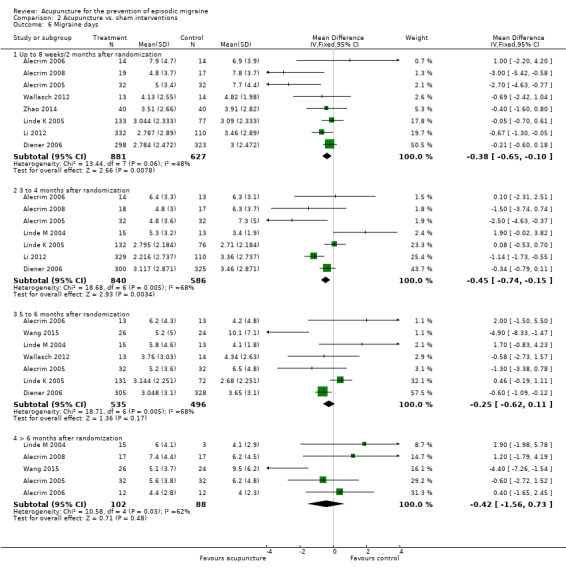

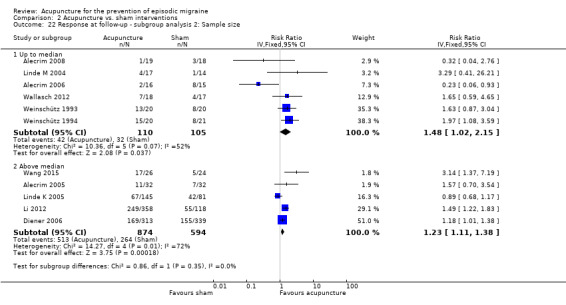

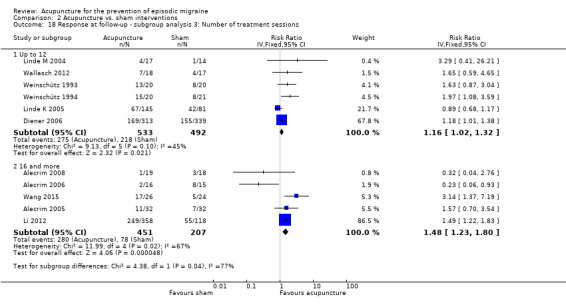

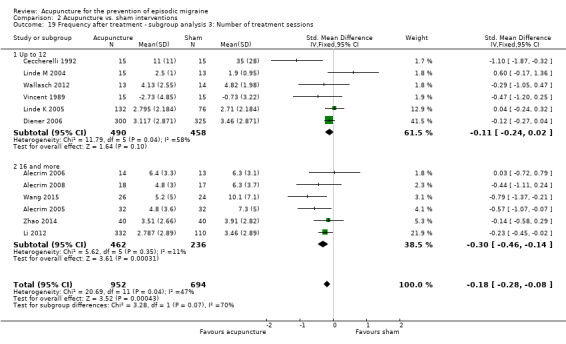

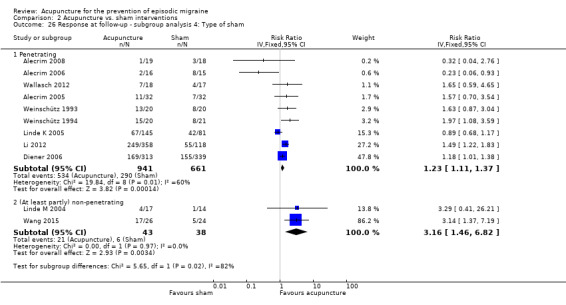

Comparisons with sham interventions

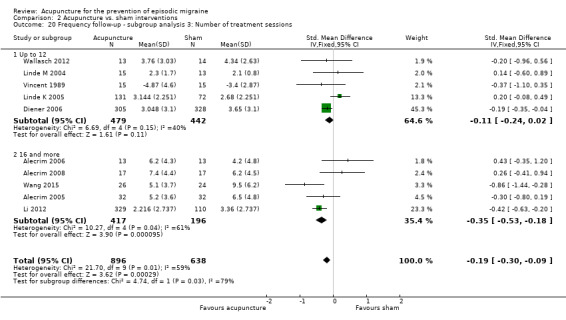

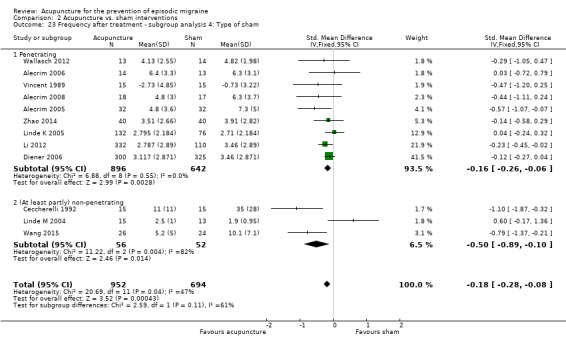

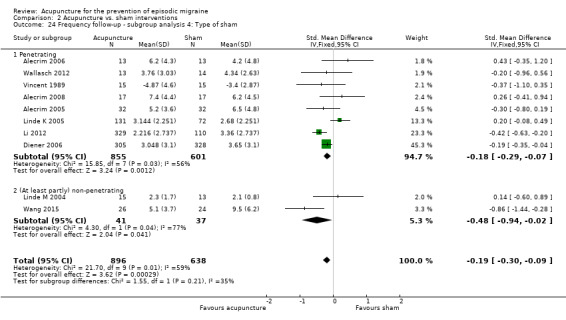

Both after treatment (12 trials providing data from 1646 participants) and at follow‐up (10 trials, 1534 participants) acupuncture was associated with a small but statistically significant frequency reduction over sham in the fixed‐effect analyses (Figure 6). The SMD was ‐0.18 (95% ‐0.28 to ‐0.08; P value from the Chi² test for heterogeneity = 0.04, I² = 47%) after treatment and ‐0.19 (95% ‐0.30 to ‐0.09; P value from the Chi² test for heterogeneity = 0.01, I² = 59%) at follow‐up. The results of the random‐effects models were similar (SMD ‐0.24; 95% CI ‐0.41 to ‐0.07 for post‐treatment, SMD‐0.16; 95% CI ‐0.37 to 0.04 at follow‐up).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Acupuncture vs. sham interventions, outcome: 2.1 Headache frequency

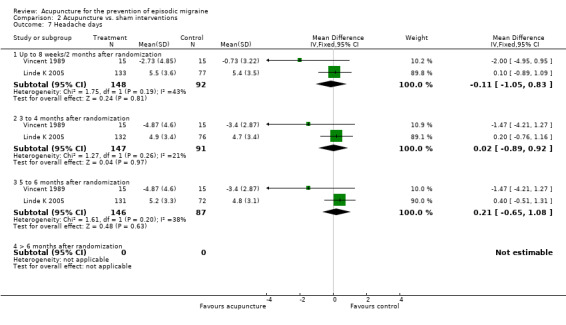

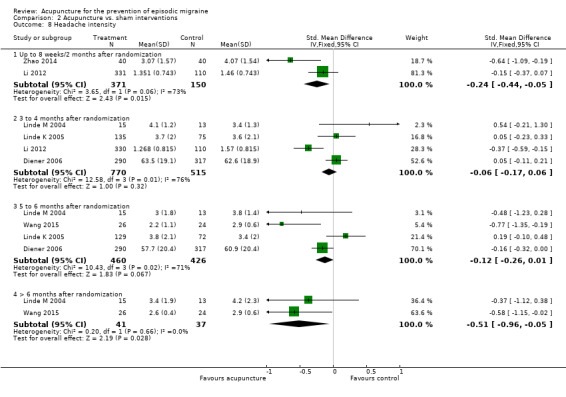

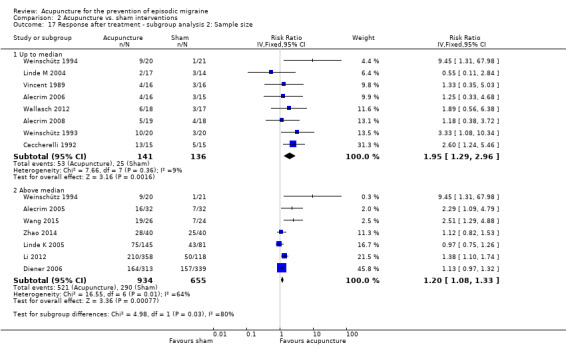

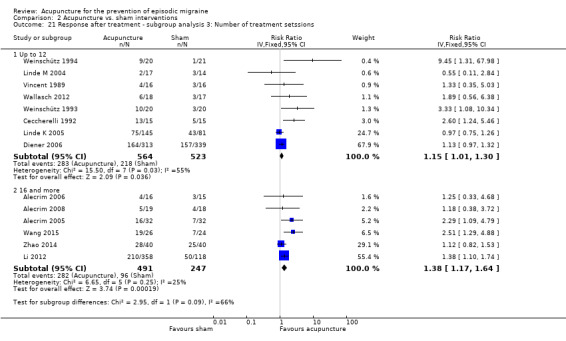

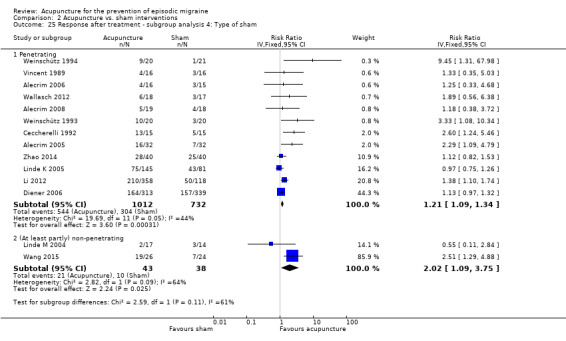

After treatment, headache frequency at least halved in 50% of participants receiving true acupuncture and 41% receiving sham acupuncture (pooled RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.36; P value = 0.02, I² = 48%; 14 trials, 1825 participants) and at follow‐up in 53% and 42%, respectively. The pooled fixed effects RR was 1.23 (95% CI 1.11 to 1.36; P value from the Chi² test for heterogeneity = 0.02, I² = 48%; 14 trials, 1825 participants) after treatment and 1.25 (95% CI 1.13 to 1.39; P value from the Chi² test for heterogeneity = 0.004, I² = 61%; 11 trials, 1683 participants) at follow‐up (Figure 7). The corresponding NNTB would be 11 (95% CI 7.00 to 20.00) after treatment and 10 (95% CI 6.00 to 18.00) at follow‐up. Random‐effects RRs were 1.39 (95% CI 1.14 to 1.69) and 1.33 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.70). The results were dominated by the three large, high‐quality trials (Diener 2006; Li 2012; Linde K 2005; 75% and 82% weight, respectively, in the meta‐analyses). We consider the findings for the outcomes headache frequency and response both after treatment and at follow‐up as moderate quality evidence (indication of heterogeneity and small effect sizes leaving magnitude and statistical significance of effect open to some change with more trials). The time windows analyses yielded findings which were consistent with our main analyses (Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4). Specific frequency outcomes as well as intensity, analgesic use and headache scores were typically available for less than half of the trials (Analysis 2.5; Analysis 2.6; Analysis 2.7; Analysis 2.8; Analysis 2.9; Analysis 2.10).

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Acupuncture vs. sham interventions, outcome: 2.2 Response (at least 50% frequency reduction)

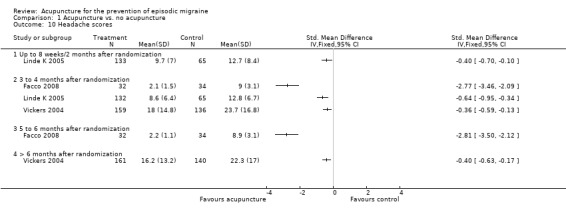

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture vs. sham interventions, Outcome 3 Headache frequency (various measures).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture vs. sham interventions, Outcome 4 Response.

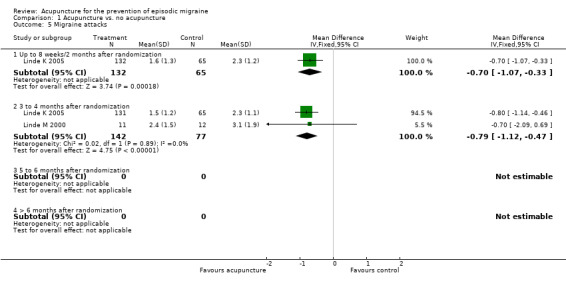

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture vs. sham interventions, Outcome 5 Migraine attacks.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture vs. sham interventions, Outcome 6 Migraine days.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture vs. sham interventions, Outcome 7 Headache days.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture vs. sham interventions, Outcome 8 Headache intensity.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture vs. sham interventions, Outcome 9 Analgesic use.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture vs. sham interventions, Outcome 10 Headache scores.