Introduction

The Current State of Asthma Management

In 2016, asthma is too often viewed as a monolithic entity. Thus, when the diagnosis of “asthma” is made it is viewed as appropriate to turn towards any of several guidelines, such as those published by the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program1, and initiate treatment based largely on the patient’s degree of severity or control. The over-arching theme of these asthma management guidelines being that for more than mild intermittent disease, the mainstay of treatment should be inhaled corticosteroids (CCS). That uniform guidelines will be universally effective for all patients is only logical if it were true that all “asthma” comprised the same disease entity. The question then arises, do the data really support uniform approaches?

Asthma “Defined”

Historically it was seemingly easy to give a phenotypic or pathological definition of asthma. The phenotypic definition being that asthma comprises obstructive lung disease with complete reversibility after the addition of bronchodilators or corticosteroids in the setting of concomitant bronchial hyperreactivity. And the pathological definition being that asthma comprises a disease of eosinophilic bronchitis characterized by a robust type 2 cytokine response (interleukin (IL-4), IL-5, and IL-13) that develops in the allergic setting. But what disease is it when the airway obstruction is irreversible and progressive? And similarly, is it still “asthma” when the persistent inflammatory infiltrate is non-eosinophilic and neither type 2 cytokines nor allergies are present?

Asthma Endotypes

In the future, it is likely that it will be possible to properly define many – presumably dozens or more – distinct “asthma” entities, each based upon its distinct pathogenic mechanism. Such a categorical diagnostic entity that is based upon a distinct pathogenic pathway is termed an “endotype”, an idealized concept currently nowhere near realization. Such endotypes could involve unique inherent mechanisms (genetic or gene control pathways) or extrinsic mechanisms (viruses or other pathogens, environmental exposures), or the interaction of both. For the purposes of this review, asthma will be approached as distinct phenotypes, a much less concise concept, and these phenotypes will be based primarily on their distinct pathologies, specifically into those with eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic presentations (Table I).

Table I.

Distinct asthma phenotypes

| Non-Eosinophilic | Paucigranulocytic Neutrophilic |

| Eosinophilic | Allergen-Exacerbated Idiopathic eosinophilic Aspirin-Exacerbated |

Non-eosinophilic asthma

is currently the most perplexing and challenging presentation of “asthma”. Even defining it pathologically is replete with controversy. Commonly this is associated with the increased prevalence of airway neutrophils. The problem with this literature is that it is difficult to separate the underlying “inherent” pathology from the confounding influence driven by the concomitant use of CCS. These patients are generally considered to have a more severe presentation and are usually on high dose inhaled CCS, if not oral CCS. The problem is that – in contrast to their effect on eosinophils – CCS inhibit neutrophil (PMN) apoptosis and thereby promote their accumulation in the airway. Thus it is difficult to distinguish the primary pathology of this disease from secondary influences of the CCS. Several papers argue that when inhaled CCS are withdrawn prior to performing the pathological studies, what is primarily a non- or paucigranulocytic inflammatory process is revealed2,3.

Consistent with a putative role for PMN in non-eosinophilic asthma, a role for IL-17+ T effector cells (Th17 cells) has been proposed. IL-17 through numerous mechanisms including induction of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor produces a robust neutrophilic response. The mechanism driving Th17 expression in asthma is – like much of this disease – completely unknown, however, studies have suggested a strong association between expression of airway PMN in asthmatics and presence and concentration of IL-174–7. And, more importantly, these studies reveal a strong relationship between the expression of IL-17 and asthma “severity”8. It should be noted that in the asthma literature the term “severe” is used interchangeably with the term “steroid resistant”. Either term is used to describe individuals refractory to asthma treatment – specifically those with persistent symptoms despite high dose inhaled or even oral CCS. Finally, the confusion as to whether these patients should be viewed as having neutrophilic as opposed to paucigranulocytic asthma may reflect that these are, in fact, two distinct phenotypes. This is particularly supported by a recent study showing that amongst those patients who lack a Th2 signature there are distinct populations who do or do not express a Th17 signature9.

Eosinophilic asthma

All asthma historically was considered to be eosinophilic. This includes individuals with what is termed allergen-exacerbated asthma, that is asthmatics who demonstrated sensitization to inhaled aeroallergens (atopy), have concomitant allergic rhinitis (AR), and report worsening symptoms on exposure. This phenotype is more common in childhood onset asthma10,11. The related phenotype comprises those in whom the prominent pathology remains eosinophils yet who do not demonstrate specific IgE sensitization (termed here, idiopathic eosinophilic asthma). This phenotype can present at any age but especially in adult-onset asthmatics who often have a more severe phenotype10,12. A third presentation of eosinophilic asthma comprises individuals with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. As with idiopathic eosinophilic asthma this is a phenotype most often presenting in adulthood and atopy is not an essential component. The defining features include the presence of severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps and the sensitivity to aspirin and other non-selective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase13.

Therapeutic Implications

Insofar as each of these crudely defined asthma phenotypes suggests a central pathogenic mechanism, by extension, each equally suggests phenotype-specific therapeutic interventions (Table II).

Table II.

Phenotype-specific asthma therapeutic targeting

| Pathology | Phenotype | Therapeutic Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Eosinophilic | Paucigranulocytic / Neutrophilic |

IL-17 antagonists Macrolide antibiotics, methotrexate, phosphodiesterase IV inhibitors |

| Eosinophilic | Allergen-Exacerbated | Allergen avoidance immunotherapy anti-IgE IL-4 antagonists IL-13 antagonists IL-4/IL-13 dual antagonists |

| Idiopathic eosinophilic | Corticosteroids IL-5/IL-5R antagonists |

|

| Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease |

Leukotriene modifiers Aspirin desensitization |

Therapeutics for paucigranulocytic/neutrophilic asthma

To the extent that neutrophilic asthma is mediated by an IL-17 high milieu, IL-17antagonists should be effective therapeutics. This led to at least one clinical trial of an anti-IL-17 receptor antibody, brodalimumab, in asthma, an antibody that blocks engagement of IL-17 and the structurally related cytokine, IL-25 to their receptors14. To enrich for non-eosinophilic subjects, this study’s primary criteria for inclusion was the presence of inadequate control despite regular use of inhaled CCS. Unfortunately, this study did not reach its primary objectives of improved asthma control and lung function although a retrospective analysis suggested improvement in a cohort with high reversibility at baseline. As such future studies with this drug are not being considered. In retrospect this result may not have been surprising as it is clear from the numerous IL-5 antagonist studies that perhaps the largest cohort of inhaled steroid resistant asthmatics is comprised of those who, in fact, do have persistent eosinophilic disease refractory to the apoptosis-inducing influences of CCS. And, as noted above, even in Th2 low asthma, a large subset may exist who do not express IL-179. As these patients do comprise a large component of refractory asthmatics, future studies with these and related agents are essential but will demand development of biomarkers for the “IL-17/Th17” high patients who are scattered amongst the steroid-resistant asthma populations.

Therapeutics for allergen-exacerbated asthma

Many studies have demonstrated the benefit of allergen avoidance. However, what is intriguing in the most definitive studies of aeroallergen avoidance15–17 is that while demonstrating impressive improvement in lung function, both airway hyperreactivity (AHR) and airway inflammation (sputum eosinophilia) persisted (Table II). The implication of this observation has to be that once the disease is established, asthma-associated inflammation and AHR can persist independent of allergen exposure – the significance of which will be discussed below. In addition to allergen avoidance (and immunotherapy), the other therapeutic implication for allergen-exacerbated asthma is the use of IgE targeting therapeutics, specifically omalizumab. Omalizumab ultimately received FDA approval primarily on the basis of its ability to inhibit asthma exacerbations18–20 and this includes the seasonal asthma exacerbations driven by rhinovirus infections21,22. Quite surprisingly, this agent had less influence on asthma symptoms and rescue bronchodilator use and no discernible influence on lung function23. The implication of this observation has to be that although central to asthma exacerbations – as with allergen exposure – once the disease is established, asthma-associated inflammation and AHR can persist independent of IgE.

IL-4 / IL-13 / dual antagonists

Given the essential role of IL-4 and IL-13 in driving the IgE isotype switch, their antagonists would be obvious considerations in patients with allergen-exacerbated asthma. The antagonisms of these cytokines (reviewed in24,25) also seems logical through their capacity to drive goblet cell metaplasia, enhanced bronchial hyperreactivity, smooth muscle hypertrophy, and increased expression of chemokines and adhesion molecules central to recruitment of eosinophils and other inflammatory cells. A distinct “signature” of proteins induced by these cytokines can be identified and for IL-13 these include the protein periostin. Periostin is a secreted matrix protein that plays important roles in tissue injury and wound repair. In IL-13-exposed epithelial cells, it contributes to their transformation into mesenchymal stem cells that lack polarity and cell-to-cell adhesion. Periostin also activates airway fibroblasts, thereby contributing to remodeling. In development, periostin is physiologically produced by obsteoblasts, making it impossible to use its serum concentrations as a biomarker for IL-13 in children and adolescents. Serum periostin can thereby be utilized as a biomarker for the presence of an IL-13hi phenotype, that might predict responsiveness to IL-13 antagonism. Individual IL-4 antagonists ultimately failed large scale clinical trials and are no longer being developed. However, IL-13 antagonism (anti-IL-13 antibodies) and antibodies that block engagement of both IL-4 and IL-13 to their shared receptor (anti-IL-4Rα antibodies) both show promise and are in varying stages of development for asthma (and atopic dermatitis)26–30. And, in asthma, the efficacy of IL-13 antagonists was largely confined to the cohort demonstrating the IL-13hi biomarker periostin31. Again, what also seems intriguing about these studies is that while have influences on various parameters of asthma including lung function and symptoms, the more striking influence was the prevention of asthma exacerbations. Implying – as with allergen and IgE targeting interventions – that although central to asthma exacerbations, once established, asthma-associated inflammation and AHR can persist independent of IL-4/IL-13.

Therapeutics for idiopathic eosinophilic asthma: Corticosteroids

CCS are considered the most effective therapeutic intervention and are the central recommendation of current asthma guidelines. Their efficacy in asthma reflects in large part their ability to induce eosinophil apoptosis. To the extent that CCS inhibit PMN apoptosis and as such promote their long-term survival it is plausible that these agents could paradoxically worsen asthma control amongst asthmatics who do not have an eosinophilic phenotype. Amazingly, this concept was recognized almost as soon as CCS became available as asthma therapeutics, with a 1958 paper specifically stating that responsiveness to prednisolone was largely limited to those with eosinophils in their sputum32. This concept has been only recently rediscovered, for example, in a 2010 study in which inhaled CCS were withdrawn until patients either developed loss of asthma control or for 28 days3. At that time, each subject’s asthma was defined as being either non-eosinophilic (paucigranulocytic) or eosinophilic (as defined by ≥2% eosinophils in induced sputum samples). After inhaled CCS were re-administered, therapeutic benefit was restricted to subjects with eosinophilic disease (Table IV).

Table IV.

Steroid response in eosinophilic and non-eosinophilic asthma*

| Eosinophilic Asthma | Non-Eosinophilic Asthma |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACQ | 48/60 (80%) | 13/28 (46%) | .001 |

| FEV1 | 48/60 (80%) | 4/28 (14%) | <.001 |

| PC20AMP | 36/49 (73%) | 12/28 (43%) | .008 |

| FENO | 44/59 (75%) | 9/28 (32%) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ACQ – asthma control questionnaire; FENO – fractional exhaled nitric oxide.

Adapted from3

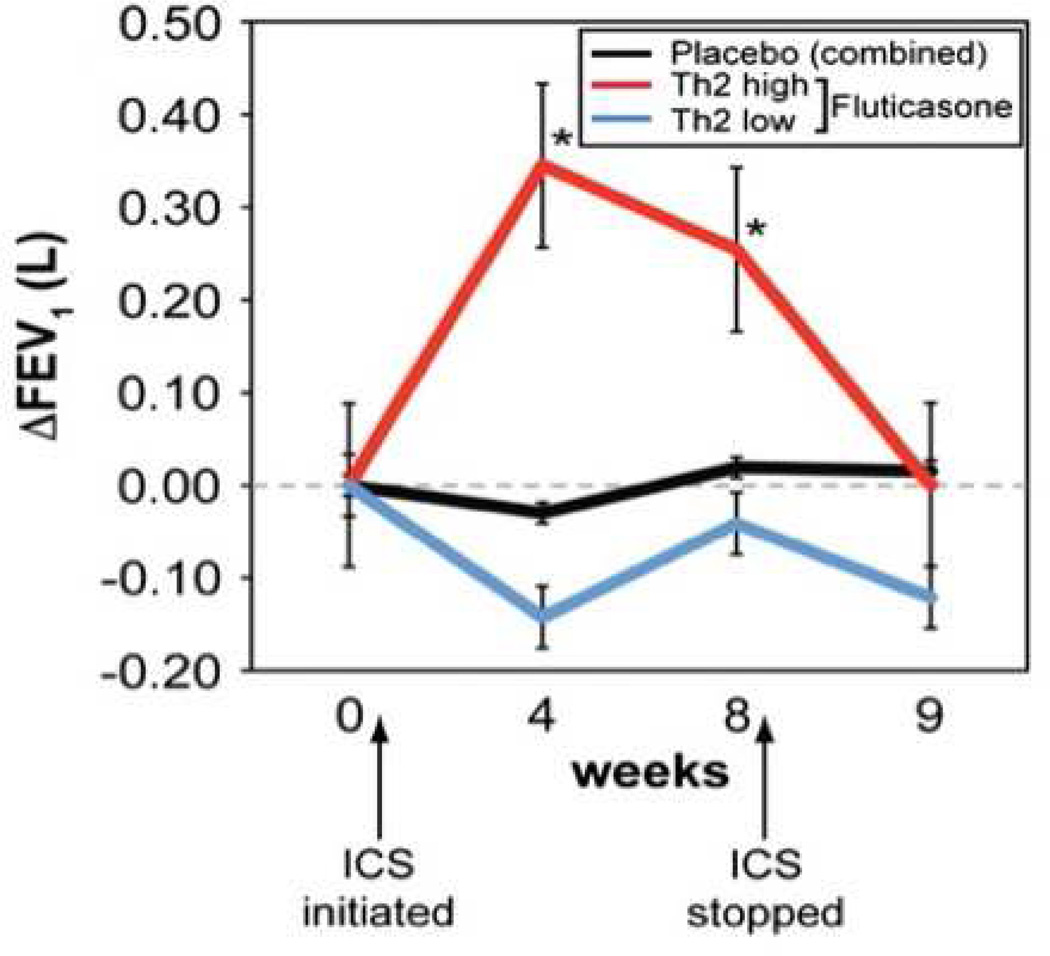

Subsequently, and even more compellingly, this concept that CCS might be minimally or perhaps even ineffective was confirmed in a study by Woodruff et al.33. This study involved collecting bronchoscopic samples from asthmatics from whom inhaled CCS were withheld and then performing protein analyses. This approach identified two distinct cohorts of asthmatics, one characterized by a type 2 cytokine signature (“Th2 high”) and the other that was termed “Th2 low”. As might be predicted, in addition to elevated IL-5 and IL-13, the Th2-high cohort subjects were distinguished by having elevated IgE and increases in both sputum and BAL eosinophils. In contrast, the Th2 low cohort had BAL eosinophil numbers indistinguishable from that of healthy controls, thus fitting into the non-eosinophilic (paucigranulocytic) phenotype. The key finding of this study, however, was the impact of this phenotypic dichotomy on response to the subsequent addition of inhaled CCS. Only the Th2 high subjects demonstrated clinical improvement after introduction of inhaled CCS (figure 1). This is a stunning result. The implication being that if inhaled CCS are given to large cohorts of asthmatics – as per the recommendation of current asthma management guidelines – no doubt a statistically significant benefit will be observed amongst the entire population. However, a large segment of the asthmatic population exists, perhaps as many as 1/3rd, amongst whom inhaled CCS provide no benefit (and if, indeed, their asthma is neutrophilic they might even be harmed by CCS – as suggested by the slight drop in FEV1 observed in figure 1):

Figure 1.

Responsiveness of Th2 high asthma to inhaled steroids. FEV1 at baseline, after 4 and 8 weeks on fluticasone (500 µg BID), and 1 week after the cessation of fluticasone (week 9) according to cohort. Reproduced with permission from32.

Interleukin-5 Antagonism

The newest approach specifically targeting eosinophilic asthma involves antagonism of IL-5, reflecting in large part its role as the only known eosinophil hematopoietin. Hematopoietic stem cells grown in the presence of IL-5 differentiate into pure populations of eosinophils and in the absence (or blockade) of IL-5 eosinophils are largely precluded from developing. In addition, IL-5 is an important survival and activation factor for mature eosinophils. Thus targeting IL-5 has been one of the more inviting targets for biotherapeutics being developed for asthma. Very surprisingly, early studies failed to demonstrate meaningful benefit from these agents despite achieving their promise of eliminating bone marrow and circulating eosinophils34. Subsequent studies, however, have realized the potential of this therapeutic approach. In retrospect, and consistent with the focus of this article, the most important requirement for identifying a benefit for eosinophilia was limitation of study enrollment as much as possible to subjects with eosinophilic asthma. Thus, two critical studies in 2009 demonstrated benefit of anti-IL-5 in asthma but only when enrollment was limited to those with sputum eosinophilia persisting in the presence of CCS35,36. A key finding of both of these studies is that anti-IL-5 had very little influence on asthma symptoms, rescue bronchodilator use, or lung function, primarily acting to prevent asthma exacerbations. The implication of this observation, again, has to be that – as with allergen exposure and IgE – although central to asthma exacerbations, once the disease is established, asthma-associated inflammation and AHR persist, in this case, independent of eosinophilia, which may have only modest influences on day-to-day asthma symptoms or degree of control. Since induced sputum would be an unacceptable basis for determining appropriateness of prescribing IL-5 blocking agents, the more recent studies that led to FDA approval for this modality focused instead on peripheral eosinophilia as a flawed but adequate biomarker for airway eosinophilia. In 2 studies published in 2015, in patients with elevated absolute eosinophil counts (AECs) despite high dose CCSs, anti-IL-5 was shown to reduce steroid requirements of oral steroid-dependent subjects and reduce asthma exacerbations37,38. In the latter study38, in the retrospective analysis of subjects with particularly high AECs (≥500/µL) impacts on lung function were also observed. More recently, a second anti-IL-5 antibody was also reported to reduce exacerbation rates and improve lung function in uncontrolled exacerbation-prone asthmatics with elevated AECs39.

So how does a type 2 cytokine milieu get generated?

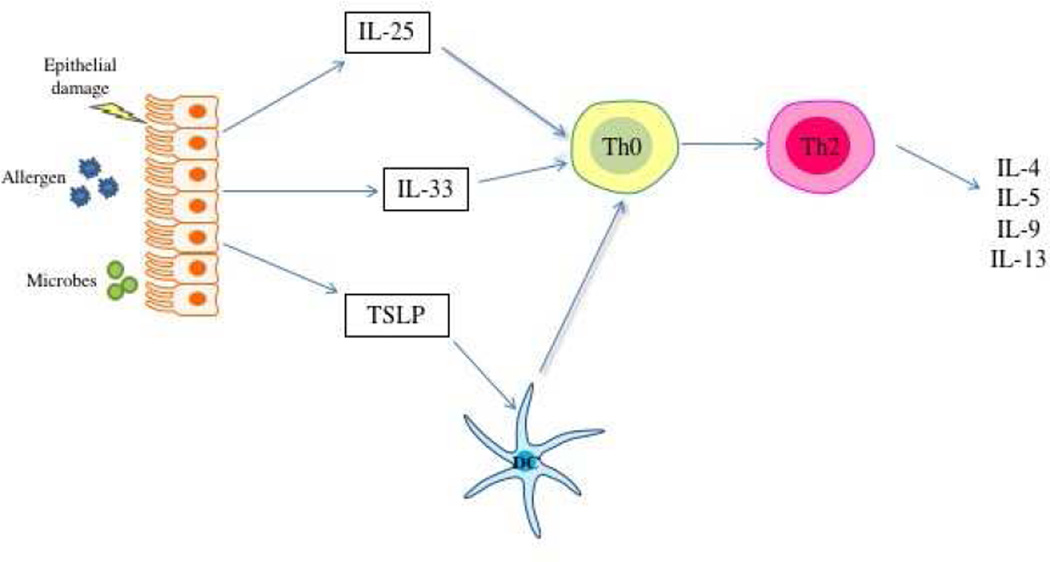

The failure of biotherapeutic agents that target specific mediators of Th2 inflammation to more comprehensively ameliorate asthma has led to consideration of the inviting prospect of targeting more “upstream” mediators. That is the targeting of mediators that underlie the development of the Th2 inflammatory state. There are numerous factors that influence the tendency of a naive T helper lymphocyte to differentiate down the Th2 pathway, including antigen concentration, affinity, and many others. But current understanding is that the most important factor involves a cytokine milieu created in asthma by airway epithelial cells (ECs). Current understanding of immunology recognize that the immune system will generally ignore harmless foreign molecules, such as allergens, unless that protein is accompanied by a signal that suggests a threat to the host. Such signals comprise molecular patterns that are derived from pathogens (that is, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and also molecular patterns generated by host cells themselves in response to perceived “danger” (danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)). Allergic diseases develop when the usual state of immune ignorance breaks down and the host responds to these otherwise benign allergens with the production of DAMPs. This model suggests that ECs sense that aeroallergens are somehow a “danger,” and furthermore misconstrue that danger as being driven by invasive helminths. As a result, ECs promote an environment where allergen-specific Th2 effector responses develop. Three EC-derived cytokines comprise danger signals that are central to this process: IL-25, IL-33, and TSLP (figure 2a)40–43. IL-25 and IL-33 act directly upon naive CD4+T helper cells to drive their differentiation down the Th2 pathway. In contrast, TSLP acts primarily on dendritic cells (DCs) inducing in them the tendency to drive any responding T helper cell to differentiate down the Th2 pathway.

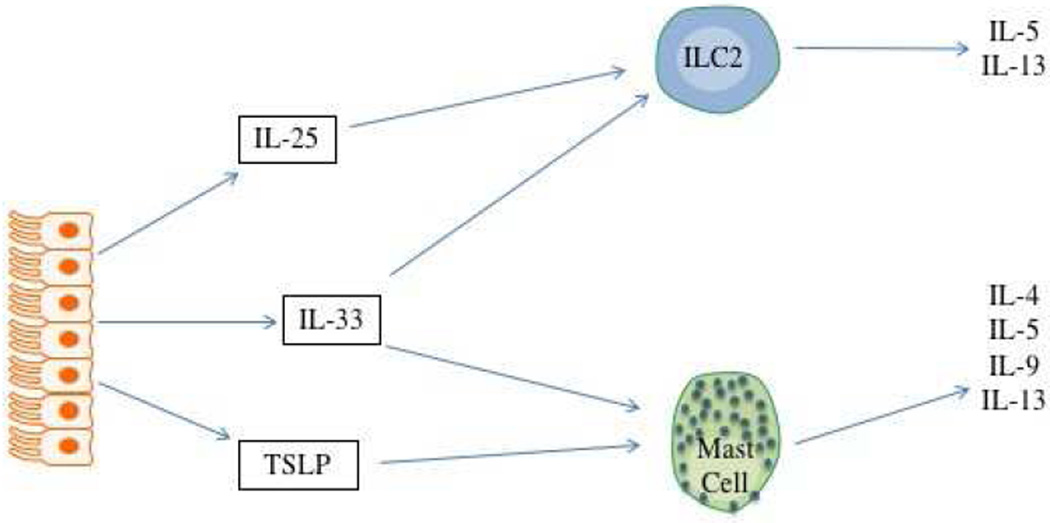

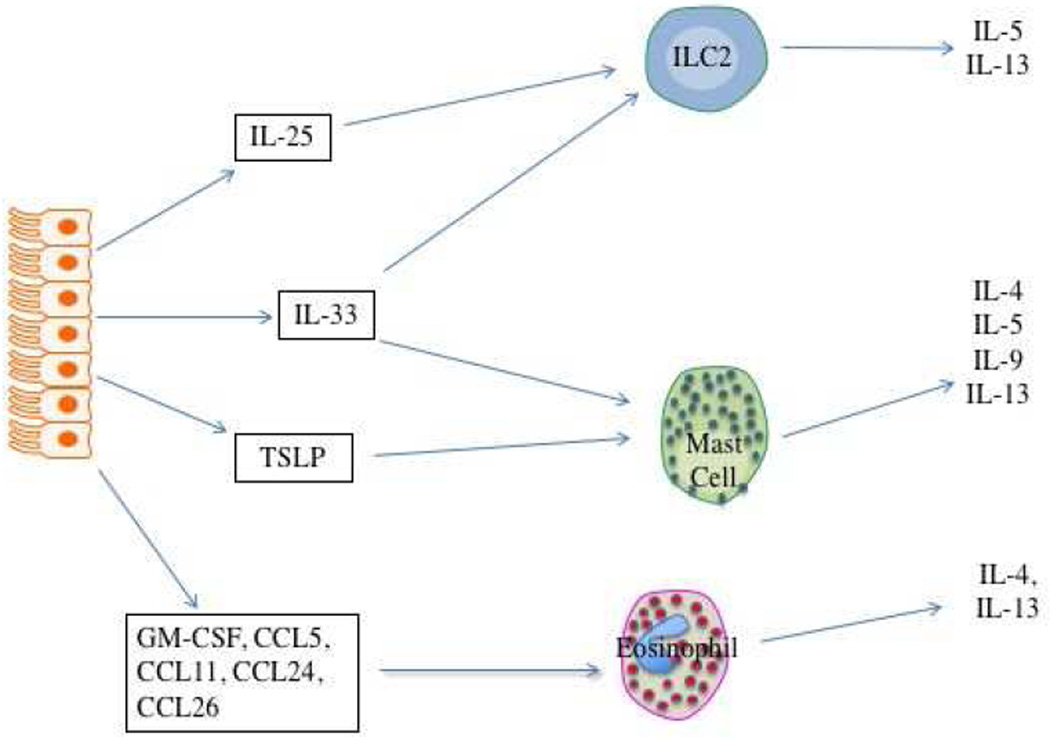

Figure 2.

Airway epithelial cell contribution to type 2 inflammation in asthma. Figure 2a. Epithelial cell derived IL-25, IL-33, and TSLP drive differentiation of Th2 effector cells via either direct influence on naïve T cells (IL-25 and IL-33) or influencing the function of antigen-presenting DCs (TSLP). Figure 2b. Once expressed, these cytokines do not require T effector lymphocytes to produce this type 2 cytokine milieu and can drive IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13 secretion from ILC2s and eosinophils. Figure 2c. Other cytokines and chemokines produced by these epigenetically-modified epithelial cells drive eosinophil recruitment and activation, again without the need for allergen-dependent Th2 lymphocytes.

Once these EC cytokines are expressed, however, they do not actually require Th2 effector cells to produce the Th2 cytokine environment. Many cells in addition to T helper cells produce some or all of the “Th2 cytokines”, that is IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13. The capacity of this Th2 milieu to be generated by other cell types has led to the current preference for the term “type 2 cytokine” rather that “Th2 cytokine” milieu. These other cell types include CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells, eosinophils, basophils, mast cells, and the more recently described type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s)44. ILC2s have gained particular interest recently regarding their role in driving allergic inflammation. These lymphocytes lack T cell antigen receptors and do not respond in an antigen-dependent fashion. Instead, they respond to numerous inflammatory signals to secrete their cytokines. In ILC2 cells these cytokines are pre-programmed to be generated and thereby like mast cells and eosinophils, they can secrete these type 2 cytokines rapidly in response to activating signals. This is in contrast to T effector cells which must be engaged by antigen-presenting DCs and undergo several cycles of replications before they begin to secrete cytokines – a process that can take up to 5–7 days. Amongst the signals driving their secretion of IL-5 and IL-13 are EC-derived IL-25 and IL-33. Similarly, all 3 cytokines can drive mast cells to rapidly secrete their preformed type 2 cytokines. This creates the scenario that once driven to produce IL-25, IL-33, and TSLP, epithelial cells can produce a type 2 cytokine milieu that will persist even in the absence of ongoing antigen exposure or the presence of T effector cells (figure 2b). Additionally, EC are also characterized by expression of numerous other mediators associated with allergic inflammation including cytokines and chemokines associated with eosinophilic recruitment and activation such as the eotaxins and RANTES (CCL5, CCL11, CCL24, CCL26), GM-CSF, and others (figure 2c).

Asthma as a disease of epigenetic tissue modification

Epigenetics refers to the molecular processes that modify DNA and chromatin to regulate cell-specific gene expression, a process that underlies tissue differentiation. For example, epigenetics drives the differentiation, of stem cells into liver cells characterized by a “liver” gene signature. This epigenetic modification of DNA and chromatin explains how cellular differentiation is preserved in these liver cells during life-long cell division. That is, these processes explain how after DNA is repackaged into chromosomes at the time of cell division the subsequent “daughter” cells recall the memory of their hepatic differentiation. This raises the question of whether asthma could comprise a similar state of epigenetic modification. Current studies suggest that airway epithelial cells have been epigenetically modified such that they – and their daughter cells and their daughter’s daughter cells ad infinitum– retain the capacity to express an asthma-associated gene signature45 (figure 2c). In addition to cytokines and chemokines, this asthma EC signature likely includes genes associated with both goblet cell metaplasia and with promotion of bronchial hyperreactivity. This suggests the differentiation of “airway epithelial cells” into pathogenic “asthmatic airway epithelial cells.” Such differentiated cells will constitutively produce levels of the cytokines and chemokines requisite to drive a smoldering background level of airway inflammation but rapidly and robustly produce a surge in production of these mediators in response to agents that drive asthma exacerbations, such as allergens and especially respiratory viral infections. Just as epigenetics drives the life-long differentiation of liver cells, this differentiation will be preserved forever in the life of the descendants of the original “asthmatic airway epithelial cells.” How such epigenetic modification occurs is not known and will not be easy to discern, as by the time the asthma diagnosis is clinically apparent the original insult may have long since been resolved. Viral infections are capable of producing long-term epigenetic changes in tissue and such a mechanism would be consistent with our patients who describe their disease as presenting “as a cold that never went away46.” And, importantly, while not necessarily essential for the persistence of asthma-associated airway inflammation, adaptive Th2 immune responses do drive EC epigenetic changes and as such almost certainly have an essential role in initiating asthma. Either way, once asthmatic differentiation is programmed into the EC, it is unlikely to be unprogrammed and the subject will remain afflicted with asthma for these rest of his or her life – exactly what we see in clinical practice (at least with adult asthmatics).

Implications for pharmacologic biotherapeutic interventions

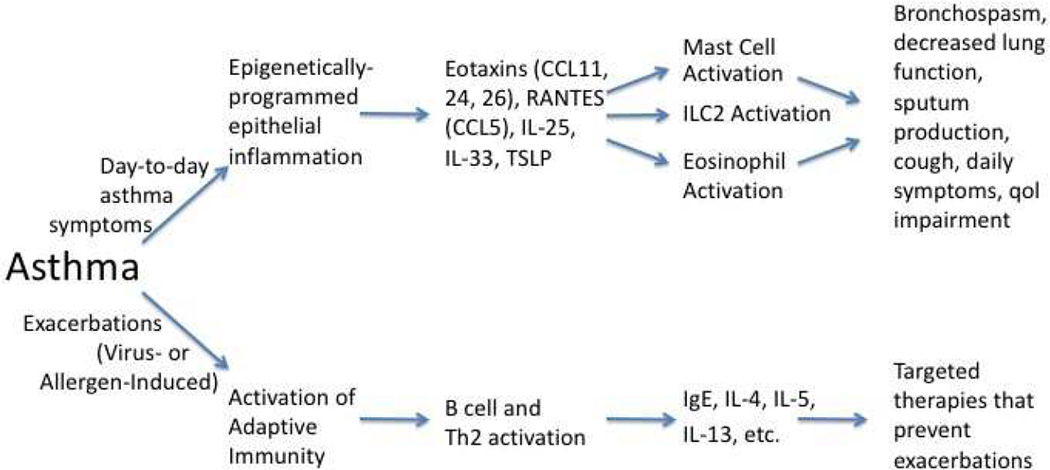

This concept of asthma as a disease primarily driven by epigenetically modified ECs has intriguing implications, in particular for all of the earlier observations regarding clinical responses to biotherapeutic interventions. As reiterated throughout this paper, interventions targeting adaptive immune responses of B and T effector cells, whether they be allergen avoidance, IgE blockade, or cytokine antagonism do a better job preventing asthma exacerbations than they do day-to-day asthma symptoms, airway hyperreactivity, and lung function. One interpretation of this consistent finding is that exposures to allergens, respiratory viruses, and other triggers drives a surge in the adaptive immune system, surges that when blocked by targeted interventions, prevents the subsequent asthma exacerbations. The “smoldering” inflammation driven by epigenetically-modified epithelial cells with their expression of low levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines but also the various genes responsible for goblet cell metaplasia, airway hyperreactivity, and others, are more responsible for day-to-day asthma symptoms and lung function. However, this component of asthma is relatively refractory to currently available biotherapeutic interventions that instead primarily target the cytokine “storm” driven by the adaptive immune responses during asthma exacerbation.

The implication is that asthma – once fully established – is no longer primarily a disease requiring continuous engagement of the adaptive immune system, but becomes instead a disease that can persist for the life of the patient without need for further engagement of T effector and B cells. This argument is particularly supported by one other observation. If asthma were just a disease of the adaptive immune system, then everyone with allergic rhinitis would have asthma. By definition, all AR patients have a full repertoire of differentiated allergen-specific Th2 lymphocytes and have demonstrated their production of IgE by allergen-specific B cells. And, indeed, the lung mast cells of AR patients are “coated” with allergen-specific IgE as evinced by the ability to generate an immediate phase bronchospastic response to inhaled allergen. However, only in asthmatics are late phase responses and protracted changes in airway hyperreactivity observed. And since this cannot be explained by any differences in adaptive immunity, this must reflect distinct inherent features of the asthmatic’s lung. In summary, this suggests the hypothesis that allergens, rhinovirus, and other triggers – acting through the adaptive immune system – drive asthma exacerbations. However, allergens and other external triggers may not be necessary to drive airway inflammation, airway hyperreactivity, bronchospasm, and day-to-day asthma symptoms (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Model of roles of innate and adaptive immunity in asthma. See text for details.

Conclusion

In summary, the current availability of biotherapeutics targeting “downstream” allergy mediators such as IgE and IL-5 and perhaps in the near future, IL-13 is an exciting vindication of molecular medicine. However, biotherapeutics must be targeted to individual asthma phenotypes and – as our understanding of this disease improves – ideally to individual endotypes. In the future inviting biotherapeutic targets for type 2 cytokine-driven asthma are the airway epithelial-derived cytokines IL-25, IL-33, and TSLP, cytokines generated in response to airway injury (virus, allergen) and then epigenetically programmed to remain constitutively expressed by these “asthmatic airway epithelial cells”. Targeting these epigenetically-programmed epithelial-derived mediators – instead of products of the adaptive immune system – may be more likely to improve day-to-day asthma symptoms, in contrast to targeting mediators of the adaptive immune system, approaches which primarily act to ameliorate asthma exacerbations.

Table III.

Allergen Avoidance in Asthma*

| Parameter | Baseline | End of Study |

|---|---|---|

| FEV1 (% predicted) | 77.7 | 122.0 |

| Methacholine PC20 | 1.90 | 2.40 |

| Sputum eosinophils (%) | 3.1 | 3.0 |

Adapted from15.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH: RO1 AI1057438, UO1 AI100799, and R56 AI120055

The author reports consulting work for Novartis/Genentech and Teva whose products are discussed in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Trial registration: Not applicable

References

- 1.Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5 Suppl):S94–S138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green RH, Brightling CE, Bradding P. The reclassification of asthma based on subphenotypes. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;7(1):43–50. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3280118a32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowan DC, Cowan JO, Palmay R, Williamson A, Taylor DR. Effects of steroid therapy on inflammatory cell subtypes in asthma. Thorax. 2010;65(5):384–390. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.126722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bullens DM, Truyen E, Coteur L, et al. IL-17 mRNA in sputum of asthmatic patients: linking T cell driven inflammation and granulocytic influx? Respir Res. 2006;7:135. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nembrini C, Marsland BJ, Kopf M. IL-17-producing T cells in lung immunity and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(5):986–994. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.033. quiz 995–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Ramli W, Prefontaine D, Chouiali F, et al. T(H)17-associated cytokines (IL-17A and IL-17F) in severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(5):1185–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nanzer AM, Chambers ES, Ryanna K, et al. Enhanced production of IL-17A in patients with severe asthma is inhibited by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in a glucocorticoid-independent fashion. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(2):297–304. e293. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore WC, Hastie AT, Li X, et al. Sputum neutrophil counts are associated with more severe asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(6):1557–1563. e1555. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choy DF, Hart KM, Borthwick LA, et al. TH2 and TH17 inflammatory pathways are reciprocally regulated in asthma. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(301):301ra129. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lotvall J, Akdis CA, Bacharier LB, et al. Asthma endotypes: a new approach to classification of disease entities within the asthma syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(2):355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie M, Wenzel SE. A global perspective in asthma: from phenotype to endotype. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126(1):166–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raundhal M, Morse C, Khare A, et al. High IFN-gamma and low SLPI mark severe asthma in mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(8):3037–3050. doi: 10.1172/JCI80911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinke JW, Borish L. Factors driving the aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease phenotype. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2015;29(1):35–40. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2015.29.4123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Busse WW, Holgate S, Kerwin E, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab, a human anti-IL-17 receptor monoclonal antibody, in moderate to severe asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(11):1294–1302. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201212-2318OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benckhuijsen J, van den Bos JW, van Velzen E, de Bruijn R, Aalbers R. Differences in the effect of allergen avoidance on bronchial hyperresponsiveness as measured by methacholine, adenosine 5'-monophosphate, and exercise in asthmatic children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1996;22(3):147–153. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(199609)22:3<147::AID-PPUL2>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Velzen E, van den Bos JW, Benckhuijsen JA, van Essel T, de Bruijn R, Aalbers R. Effect of allergen avoidance at high altitude on direct and indirect bronchial hyperresponsiveness and markers of inflammation in children with allergic asthma. Thorax. 1996;51(6):582–584. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.6.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grootendorst DC, Dahlen SE, Van Den Bos JW, et al. Benefits of high altitude allergen avoidance in atopic adolescents with moderate to severe asthma, over and above treatment with high dose inhaled steroids. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31(3):400–408. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soler M, Matz J, Townley R, et al. The anti-IgE antibody omalizumab reduces exacerbations and steroid requirement in allergic asthmatics. Eur Respir J. 2001;18(2):254–261. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00092101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busse W, Corren J, Lanier BQ, et al. Omalizumab, anti-IgE recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of severe allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(2):184–190. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milgrom H, Berger W, Nayak A, et al. Treatment of childhood asthma with anti-immunoglobulin E antibody (omalizumab) Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):E36. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Busse WW, Morgan WJ, Gergen PJ, et al. Randomized trial of omalizumab (anti-IgE) for asthma in inner-city children. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(11):1005–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teach SJ, Gill MA, Togias A, et al. Preseasonal treatment with either omalizumab or an inhaled corticosteroid boost to prevent fall asthma exacerbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(6):1476–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNicholl DM, Heaney LG. Omalizumab: the evidence for its place in the treatment of allergic asthma. Core Evid. 2008;3(1):55–66. doi: 10.3355/ce.2008.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hershey GK. IL-13 receptors and signaling pathways: an evolving web. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(4):677–690. quiz 691. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borish L. IL-4 and IL-13 dual antagonism: a promising approach to the dilemma of generating effective asthma biotherapeutics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(8):769–770. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0147ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corren J, Busse W, Meltzer EO, et al. A randomized, controlled, phase 2 study of AMG 317, an IL-4Ralpha antagonist, in patients with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(8):788–796. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200909-1448OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wenzel S, Ford L, Pearlman D, et al. Dupilumab in persistent asthma with elevated eosinophil levels. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(26):2455–2466. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck LA, Thaci D, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(2):130–139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanania NA, Noonan M, Corren J, et al. Lebrikizumab in moderate-to-severe asthma: pooled data from two randomised placebo-controlled studies. Thorax. 2015;70(8):748–756. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thaci D, Simpson EL, Beck LA, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical treatments: a randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):40–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corren J, Lemanske RF, Hanania NA, et al. Lebrikizumab treatment in adults with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1088–1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown HM. Treatment of chronic asthma with prednisolone; significance of eosinophils in the sputum. Lancet. 1958;2(7059):1245–1247. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(58)91385-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, et al. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(5):388–395. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0392OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flood-Page P, Swenson C, Faiferman I, et al. A study to evaluate safety and efficacy of mepolizumab in patients with moderate persistent asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(11):1062–1071. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-085OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haldar P, Brightling CE, Hargadon B, et al. Mepolizumab and exacerbations of refractory eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(10):973–984. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nair P, Pizzichini MM, Kjarsgaard M, et al. Mepolizumab for prednisone-dependent asthma with sputum eosinophilia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(10):985–993. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bel EH, Wenzel SE, Thompson PJ, et al. Oral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of mepolizumab in eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1189–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, et al. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1198–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castro M, Zangrilli J, Wechsler ME, et al. Reslizumab for inadequately controlled asthma with elevated blood eosinophil counts: results from two multicentre, parallel, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(5):355–366. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharkhuu T, Matthaei KI, Forbes E, et al. Mechanism of interleukin-25 (IL-17E)-induced pulmonary inflammation and airways hyper-reactivity. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36(12):1575–1583. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang YH, Angkasekwinai P, Lu N, et al. IL-25 augments type 2 immune responses by enhancing the expansion and functions of TSLP-DC-activated Th2 memory cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204(8):1837–1847. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu YJ, Soumelis V, Watanabe N, et al. TSLP: an epithelial cell cytokine that regulates T cell differentiation by conditioning dendritic cell maturation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:193–219. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borish L, Steinke JW. Interleukin-33 in asthma: how big of a role does it play? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11(1):7–11. doi: 10.1007/s11882-010-0153-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klein Wolterink RG, Kleinjan A, van Nimwegen M, et al. Pulmonary innate lymphoid cells are major producers of IL-5 and IL-13 in murine models of allergic asthma. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42(5):1106–1116. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borish L, Steinke JW. Beyond transcription factors. Allergy Clin Immunol Int. 2004;16:20–27. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walter MJ, Morton JD, Kajiwara N, Agapov E, Holtzman MJ. Viral induction of a chronic asthma phenotype and genetic segregation from the acute response. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(2):165–175. doi: 10.1172/JCI14345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]