Abstract

Successful vaccination policies for protection from bacterial meningitis are dependent on determination of the etiology of bacterial meningitis. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples were obtained prospectively from children from 1 month to ≤ 18 years of age hospitalized with suspected meningitis, in order to determine the etiology of meningitis in Turkey. DNA evidence of Neisseria meningitidis (N. meningitidis), Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae), and Hemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) was detected using multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR). In total, 1452 CSF samples were evaluated and bacterial etiology was determined in 645 (44.4%) cases between 2005 and 2012; N. meningitidis was detected in 333 (51.6%), S. pneumoniae in 195 (30.2%), and Hib in 117 (18.1%) of the PCR positive samples. Of the 333 N. meningitidis positive samples 127 (38.1%) were identified as serogroup W-135, 87 (26.1%) serogroup B, 28 (8.4%) serogroup A and 3 (0.9%) serogroup Y; 88 (26.4%) were non-groupable. As vaccines against the most frequent bacterial isolates in this study are available and licensed, these results highlight the need for broad based protection against meningococcal disease in Turkey.

Keywords: Meningitis, Turkey, etiologic agents, N. meningitidis, S. pneumoniae, Hib, epidemiology, surveillance

Introduction

Acute bacterial meningitis is one of the most severe infectious diseases, not only causing physical and neurologic sequelae, but also continues to be an important cause of mortality.1,2 Although most disease occurs in infants and young children, high incidence may be observed in healthy older children and adolescents. Despite the continuing development of new antibacterial agents, bacterial meningitis fatality rates remain high, with reported rates between 2% and 30%.3,4 Furthermore, 10–20% of survivors suffer permanent sequel, including epilepsy, mental retardation, or sensorineural deafness.5-7

In infants and children, before the introduction of modern vaccines, 90% of reported cases of acute bacterial meningitis were caused by Hemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae), or Neisseria meningitidis (N. meningitidis).8,9 Hib meningitis primarily affects very young children, most cases occurring in children from 1 mo to 3 y of age.3,9 The introduction of highly effective Hib polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines has virtually eliminated invasive Hib disease in most industrialized countries where routine Hib vaccination has been implemented.8,9

In most countries, S. pneumoniae was the next major cause of childhood bacterial meningitis, particularly in those where Hib disease has been eliminated by vaccination.10 In some European and sub-Saharan African countries, it is the second most frequently reported cause of septic meningitis after meningococcal cases.4,10 The ongoing development and introduction into routine immunization schedules of glycoconjugate pneumococcal vaccines has markedly reduced the incidence of disease caused by vaccine serotypes, initially against the seven serotypes in the first vaccine, and now with coverage increasing from 10 or 13 serotypes in recent years.

The success of these vaccines means N. meningitidis is now considered to be the leading cause of bacterial meningitis in many regions of the world, causing an estimated 1.2 million cases of bacterial meningitis and sepsis worldwide each year.11,12 There are 12 recognized serogroups of N.meningitidis, but the vast majority of invasive disease is related to six meningococcal serogroups: (Men) A, B, C, W-135, X and Y.13-15 The epidemiology and distribution of these disease-causing serogroups varies widely by geographic region: so while Men A is the most predominant disease-causing serogroup in sub-Saharan Africa and remains an important factor in parts of Asia, it now seldom if ever occurs in Western Europe or North America, where cases of Men A used to occur. In contrast, Men B and Men C dominate in the industrialized countries of North and South America,15,16 while the introduction of routine childhood vaccination with monovalent meningococcal serogroup C conjugate vaccines into Europe and Australia has markedly decreased incidence there. Serogroup W-135 has recently emerged in some parts of the world, primarily in the Middle East and Africa, in some instances causing large epidemics, and has been associated with small outbreaks in Europe due to pilgrims returning from Hajj.17 Men Y has been increasing in relative incidence over recent years in North America, South America and South Africa, and most recently, cases of Men X disease have emerged in sub-Saharan Africa. Men ACWY conjugate vaccines have been available for years but are not widely used. On the other hand, MenC conjugate vaccine has been widely used in Europe and MenA conjugate vaccine in sub-Saharan Africa through mass vaccination campaign and that their impact (MenA and MenC) has been dramatic in reducing meningitis due to the respective serotypes.15,17-19 Since 2002, in accordance with the Saudi Arabian requirements, all Turkish pilgrims to the Hajj in Mecca have received a quadrivalent meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine before travel. However, MenB and MenACWY conjugate vaccines are not yet routinely recommended for infants in Turkey. Hib vaccine was included in the Turkish immunization schedule and was administered as a separate injection in 2006 as DPT+OPV+Hib. DTaP-IPV/Hib combined vaccine replaced them in 2008. The seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV-7) has been implemented into the Turkish national immunization schedule at ages 2, 4, 6, and 12 mo of age in 2008. This was replaced with the 13-valent vaccine (PCV-13) in 2011.

As knowledge of the local epidemiology is necessary to support policymakers decision on the most appropriate vaccine to be used against bacterial meningitis, since 2005 we have been performing a nationwide hospital-based meningitis surveillance study across several regions of Turkey. We present here the results from 2005 to 2012.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This multicenter, hospital-based, prospective, epidemiological study was conducted in Turkey between February 2005 and December 2012 among children and adolescents younger than 18 y of age. The study was reviewed and approved by the Hacettepe University Institutional Ethics Committee. This ethical approval was sufficient for the other study sites as well. Patients with suspected meningitis were screened and hospitalized in 12 hospitals located in 7 regions of Turkey [Central Anatolia, Marmara, South East Anatolia, Aegean, East Anatolia, Mediterranean, and Black Sea] which provide healthcare services to approximately 32% of the Turkish population. After patients’ parents/legal guardians had given informed consent, specimens were collected for the diagnosis.

Hospital pediatricians identified suspected cases of acute bacterial meningitis based on the following standard criteria: any sign of meningitis (fever [≥38°C], vomiting [≥3 episodes in 24 h], headache, signs of meningeal irritation [bulging fontanel, Kernig or Brudzinski signs, or neck stiffness]) in children >1 y of age; fever without any documented source; impaired consciousness (Blantyre Coma Scale <4 if <9 mo of age and <5 if ≥9 mo of age)20; prostration (inability to sit unassisted if ≥ 9 mo of age or breastfeed if <9 mo of age) in those <1 y of age; and seizures (other than those regarded as simple febrile seizures with full recovery within 1 h). For each suspected case, demographic data, main clinical signs and symptoms, prior clinical history including use of antimicrobial agents, treatment, and laboratory results and outcome data were recorded on a standardized case report form.

In addition, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples were obtained from all patients <18 y of age with clinically suspected meningitis. Since the pathogens responsible for neonatal meningitis are different from older patients, neonates (patients <1 mo of age) were not included in the study.3

Laboratory analyses

Samples were analyzed if CSF had the following criteria: 1) > 10 leukocytes/mm3 in the CSF, and/or 2) higher CSF protein levels than normal for the patient's age, and/or 3) lower CSF glucose levels than normal for the patient's age. In addition, all patients who had positive test results to CSF culture, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), Gram stain, or antigen detection test were also included in the study. CSF cultures and Gram stain were performed in the local hospitals, but CSF samples (minimum of 0.5 mL) from each patient was stored at −20°C until transportation to the Central Laboratory at Hacettepe University Pediatric Infectious Diseases Unit, Ankara, Turkey for PCR analysis. If available, bacterial isolates were also sent to the Central Laboratory, where they were re-cultured on chocolate and blood agars and grown at 37°C in 5% CO2. Suspected meningococcal colonies were characterized by Gram stain, oxidase test, and rapid carbohydrate utilization test Api (API NH ref. 10400, BioMerieux, Germany). The microbiology laboratory records were crosschecked in each hospital for missing data. Hospital's databases were searched for diagnosis of meningitis. Laboratory records were crosschecked on weekly basis with the hospital database. The phenotypic determination, based on the antigenic formula (serogroup: serotype: serosubtype) of meningococcal isolates, was performed by standard methods in the Meningococcal Reference Unit, Health Protection Agency, Manchester, United Kingdom.17,21-23

All samples transferred to the Central Laboratory were stored at −80°C and thawed immediately before each test. DNA was isolated as previously reported.24 Single tube, multiplex PCR assay was performed for the simultaneous identification of bacterial agents. The specific gene targets were ctrA, bex, and ply for N. meningitidis, Hib, and S. pneumoniae, respectively.24,25 PCR was performed by using a DNA thermal cycler (GeneAmp PCR System model 9700, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). PCR positive samples were recorded as laboratory-confirmed acute bacterial meningitis.

In samples positive for N. meningitidis, serogroup prediction (A, B, C, W-135, and Y) was based on the oligonucleotides in the siaD gene for serogroups B, C, W-135, and Y, and in orf-2 of a gene cassette required for serogroup A.25,26

All amplicons were analyzed by electrophoresis on standard 3% agarose gels and visualized using UV fluorescence. A negative control consisting of distilled water and positive control consisting of an appropriate reference strain (S. pneumoniae ATCC 49613, Hib ATCC 10211, N. meningitidis serogroup C L94 5016 also known as C11 [C:16:P1.7–1.1], serogroup A M99 243594 [A:4,21:P1.20,9], serogroup Y M05 240122 [Y:NT:P1.5], serogroup W-135 M05 240125 [W135:2a: NST], serogroup B M05 240120 [B:NT:NST] were analyzed simultaneously.

Results

During 2005–2012 a total of 1452 children were hospitalized with a clinical diagnosis of meningitis. CSF sample were obtained from each patient. The mean age was 4.8 ± 4.2 y (range, 1 mo and 18 y) and the boy-to-girl ratio was 1.56:1. There were 37 deaths, 21 of whom in patients with laboratory-confirmed cases. The case-fatality rate for the laboratory confirmed cases was 3.3%. The median age of fatal cases was 11 mo (interquartile range [IQR], 4–21). The etiology of the mortality were determined N.meningitis, S. pneumoniae, and Hib as 52.4% (n = 11), 33.3% (n = 7), and 14.3% (n = 3), respectively. Bacterial meningitis was confirmed by PCR in 645 (44.4%) patients, the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis was confirmed by CSF culture only in 105 (16.2%) of these. Overall, 476 patients received various antibiotic treatments before the lumbar puncture.

Laboratory-confirmed cases and etiology

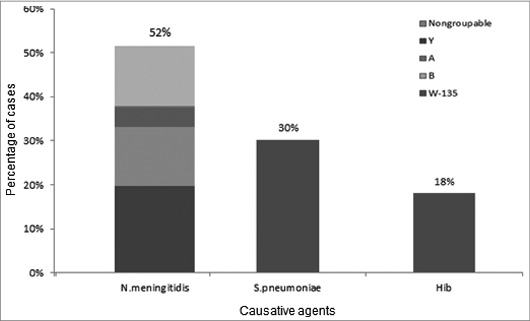

Of the 645 diagnosed cases of bacterial meningitis by PCR over the whole period of 2005–2012, 333 (51.6%) were meningococcal; 195 (30.2%) (n = 195) were pneumococcal and 117 (18.1%) were due to Hib (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of causative agents of bacterial meningitis and meningococcal serogroups in Turkey, 2005–2012. Of 645 PCR-confirmed cases, 333 (51.6%) were attributable to Neisseria meningitidis, 195 (30.2%) to Streptococcus pneumoniae, and 117 (18.1%) to Hemophilus influenzae type b (Hib). Among meningococcal meningitis, serogroup A, B and W-135 were 8.4%, 26.1%, and 38.1%, respectively. Serogroup Y was only detected 2.2%. Non-groupable cases were 26.4%.

Among meningococcal meningitis, cases of serogroup A, B and W-135 were 0.8% (n = 1), 31.1% (n = 43), and 42.7% (n = 59) in 2005–2006; 8.3% (n = 9), 35.1% (n = 38), and 17.6% (n = 19) in 2007–2008; 36.6% (n = 15), 7.3% (n = 3), and 56.1% (n = 23) in 2009–2010; and 6.5% (n = 3), 6.5% (n = 3), and 56.5% (n = 26) in 2011–2012, respectively (Table 1). Of meningococcal meningitis cases during 2005–2012, serogroup A, B and W-135 were identified in 8.4% (n = 28), 26.1% (n = 87), and 38.1% (n = 127), respectively (Fig. 1). No serogroup C was detected among meningococcal cases between 2005 and 2012. Serogroup Y was only detected in 2005–2006, representing 2.2% (n = 3) of meningococcal cases.

Table 1.

Distribution of causative agents of bacterial meningitis and meningococcal serogroups per year in Turkey

| Study Period (Year) | 2005–2006 | 2007–2008 | 2009–2010 | 2011–2012 | 2005–2012 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Causative Bacteria |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

| Serogroup W-135 | 59 | 42.7 | 19 | 17.6 | 23 | 56.1 | 26 | 56.5 | 127 | 38.1 |

| Serogroup B | 43 | 31.1 | 38 | 35.1 | 3 | 7.3 | 3 | 6.5 | 87 | 26.1 |

| Serogroup A | 1 | 0.8 | 9 | 8.3 | 15 | 36.6 | 3 | 6.5 | 28 | 8.4 |

| Serogroup C | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Serogroup Y | 3 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.9 |

| Nongroupable | 32 | 23.2 | 42 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 30.5 | 88 | 26.4 |

| N. meningitidis (Total) | 138 | 56.8 | 108 | 40.4 | 41 | 62.1 | 46 | 66.6 | 333 | 51.6 |

| S. pneumonia | 55 | 22.6 | 98 | 36.7 | 21 | 31.8 | 21 | 30.4 | 195 | 30.2 |

| H. influenzae type b | 50 | 20.6 | 61 | 22.8 | 4 | 6.1 | 2 | 2.9 | 117 | 18.1 |

| Total number of Positive Samples | 243 | 100 | 267 | 100 | 66 | 100 | 69 | 100 | 645 | 100 |

| Total number of Evaluated Clinical Samples | 408 | NA | 372 | NA | 355 | NA | 317 | NA | 1452 | NA |

Pneumococcal and Hib meningitis accounted for 22.6% (n = 55) and 20.6% (n = 50) of cases in 2005–2006; 36.7% (n = 98) and 22.8% (n = 61) in 2007–2008; 31.8% (n = 21) and 6.1% (n = 4) in 2009–2010; and 30.4% (n = 21) and 2.9% (n = 2) in 2011–2012, respectively (Table 1).

Age distribution

Among meningococcal meningitis, cases in subjects ≤1 y, 1–4 y, 5–9 y, 10–14 y, and 15–18 y old were 18.3%, 32.4%, 26.2%, 18.3%, and 4.8% in 2005–2012, respectively. Pneumococcal meningitis cases were reported in subjects ≤1 y, 1–4 y, 5–9 y, 10–14 y, and 15–18 y old as 12.3%, 44.1%, 23.1%, 11.3%, and 9.2% in 2005–2012, respectively. N.meningitidis was the predominant agent responsible for acute bacterial meningitis in children <5 y of age, in 2005–2006. Whereas, in 2007–2008 pneumococcal meningitis was the leading cause of acute bacterial meningitis, in the same age group. Among Hib meningitis, cases in subjects ≤1 y, 1–4 y, 5–9 y, 10–14 y, and 15–18 y were 14.5%, 29.9%, 27.4%, 18.8%, and 9.4% in 2005–2012, respectively. Hib meningitis was seen only one case in each 1–4 y and 15–18 y in 2011–2012. When we consider the entire study period (2005–2012), more bacterial meningitis cases were occurred in children under 5 y of age (51.3% of all cases) with a highest rate of 1–4 y (35.5%).

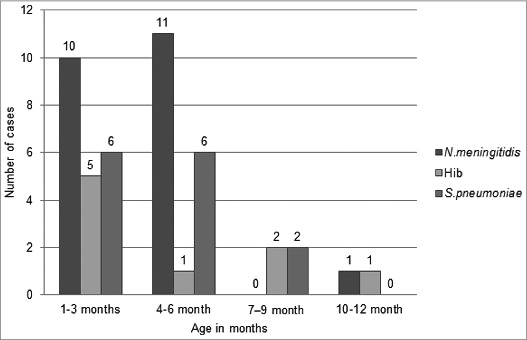

Acute bacterial meningitis in children under 1 y of age (Fig. 2) occurred mostly <6 mo of age. N.meningitidis was the leading cause of the meningitis in 6 mo, followed by S.pneumoniae. Hib represents 1/3 of the children in 1–3 mo.

Figure 2.

Age distribution of bacterial meningitis in infants in Turkey (2006–2012)

Incidence and regional distribution

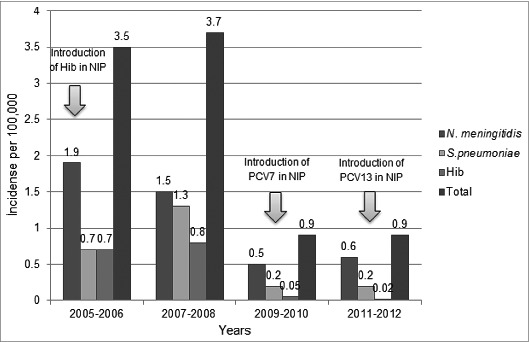

The annual incidence of acute laboratory-confirmed bacterial meningitis gradually decreased from 3.5 cases / 100,000 population in 2005–2006 to 0.9 cases/ 100,000 in 2011–2012 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Annual incidence of causative agents of bacterial meningitis per 100,000 and effect of Hib and PCV vaccinations in Turkey. Because our study centers provide service to 32% of the population of Turkey, extrapolation from the number of cases recorded was calculated for the possible number of acute bacterial meningitis cases (excluding neonatal cases) per year occur in the whole country. The population of children 1 mo through 18 y of age was calculated as 23.9 million.

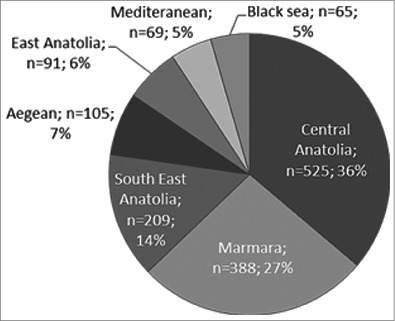

The regional distribution of etiologic pathogens during 2005–2012 showed that bacterial meningitis was most prevalent in the Central Anatolia, followed by Marmara and South East Anatolia (Fig. 4). The population of children 1 mo through 18 y of age was calculated per region according to the data of Turkish Statistical Institute. Therefore, the incidence of acute bacterial meningitis was 4.5/100.000 in Central Anatolia, 1.3/100.000 in Marmara, 8/100.000 in Southeast Anatolia, 3/100.000 in Aegean, 6/100.000 in Eastern Anatolia, 2.5/100.000 in Mediterranean, and 1/100.000 in Black Sea region in the study period of 2011–2012.

Figure 4.

Regional distribution of bacterial meningitis cases in Turkey (2005—2012)

Discussion

To efficiently implement regional and national immunization programs the availability of recent epidemiologic data on the vaccine-preventable diseases prevalent in those areas represents critical piece of information. We have monitored the incidence and nature of bacterial meningitis cases in Turkey from 2005 to 2012. At the beginning of this study period the annual incidence of acute bacterial meningitis in Turkey was 3.5 cases/ 100,000 population.24 This annual incidence decreased to 0.9 cases/ 100,000 in 2011–2012. Hib vaccination for children <1 y of age was implemented in the Turkish National Immunization Program (NIP) in 2006, leading to a marked decrease in incidence of Hib meningitis. Routine vaccination with PCV-7 for children <1 y of age was agreed on paper at the end of 2008 and included in the NIP in 2009, and PCV-7 was replaced by PCV-13 in November 2011. Between 2010–2013, approximately 97% of the target population was vaccinated with PCV.27 However, in spite of the availability of these pneumococcal vaccines; there has been no major decrease in pneumococcal meningitis incidence. This may be because the introduction of vaccination against pneumococcal disease is too recent and the effects of vaccination are not yet evident. Therefore, the main contribution to the overall decrease in annual incidence in Turkey can be attributed to the dramatic vaccination-induced decrease in Hib meningitis introduced in 2006 and with coverage of 97%.

In this study, 645 cases of laboratory-confirmed acute bacterial meningitis were recorded, but bacterial isolation was only possible in 105 (16.2%) of those confirmed cases. This may have been related to the use of antibiotics before admission to the study centers, as the majority of patients received various treatments before the lumbar puncture. Therefore, non-culture techniques might be necessary to detect the causative organisms.27 Laboratory confirmation of the etiology of acute bacterial meningitis is critical for providing optimal patient therapy and to ensure appropriate case contact management. In addition, case confirmation provides epidemiological information necessary for making decisions concerning immunization programs, and implementation of new available vaccines against the most common bacterial meningitis pathogens.24,25,28 Of the non-culture diagnostic tests, PCR is the most common method that is sufficiently accurate and reliable, especially when there is a history of antimicrobial drug use before lumbar puncture.24,29 In our study only 16,2% of cases were confirmed by CSF culture, and although bacterial culture is considered the standard method, PCR allowed to identify the etiological agent in most cases27 of acute bacterial meningitis in culture-negative patients.

We identified N. meningitidis as the most common cause of bacterial meningitis (51.6%) in Turkey, especially in children <5 y of age. Additionally, N. meningitidis was the highest reason of the fatality. The case-fatality rate (3.3%) in the present study was lower than the literature that reported between 5.3% and 26.2%.30 This result may be attributed that receiving effective hospital antibiotic treatment and reaching a more qualified health care facility for the acute meningitis episode may be easier in Turkey than the low-income countries. There were no significant variations in the incidence of the bacterial meningitis in per region according to years. However, there was large variation in the incidence of disease caused by specific serogroups, serogroup B dominating in some years and W-135 in others, while disease caused by serogroup A has increased recently; there were no serogroup C cases observed in this study, and only a small number of serogroup Y cases. These data are in contrast to those from many parts of Europe, where serogroups B and C dominate.12,31,32 The reason for the sudden decrease in serogroup B disease in Turkey is not clear as there is no serogroup B vaccine currently available, but the epidemiology of serogroup B has been observed to vary with time in many countries without any apparent reason. In the United States, the proportion of disease caused by serogroup Y has increased over the past decade to over one third of cases,33 while serogroups C has declined in many European countries since the introduction of serogroup C vaccines into routine immunization programs.21 The reason why serogroups C and Y are rare in Turkey is unclear, as no vaccine has been used against these serotypes. Several points should be taken into account: the coverage of our study centers, population dynamics, diagnostic procedures, and possible importation of serogroups such as W-135 from other countries that may have decreased the proportion of some serogroups.

The first Turkish patient with meningitis caused by serogroup W-135 was reported in 2003.22 Most of the Turkish population is Muslim, and ≈150,000 pilgrims travel annually to the Hajj in Saudi Arabia. Since 2002, all Turkish pilgrims have received a quadrivalent (A, C, W, Y) meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine before travel. Although this vaccine generates a robust immune responses against all constituent serogroups, unlike conjugate vaccines, meningococcal polysaccharide vaccines do not prevent asymptomatic carriage.24,34 The rapid rise in the proportion of cases caused by serogroup W-135 may be attributable to transmission from pilgrims returning from the Hajj carrying W-135,24 despite their vaccination with polysaccharide vaccine. Of 11 family members of pilgrims who acquired W-135 carriage at the Hajj, 10 (91%) had acquired carriage of serogroup W-135.35 This study illustrated the acquisition of meningococcal carriage, predominantly of serogroup W-135 by pilgrims attending the Hajj, the transmission to their family members on their return, as the possible explanation for the presence of W-135 meningococcal disease in Turkey. Similar observations have been made in the UK and France.17 For this reason, the Turkish National Immunization Board has decided to change recommendation from a polysaccharide to a conjugated quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine for pilgrims and Umrah visitors, which may help to reduce carriage rates and decrease the burden of W-135 in Turkey.36

This study has several limitations. First, because previous antibiotic treatment had high rates, we did not find enough laboratory-confirmed cases to drive accurate incidence rates for each pathogen, thus limiting the generalizability of those data. Second, our study likely missed many bacterial meningitis cases, particularly among case-patients whose illnesses did not meet the case definition. Despite the limitations, this project has provided useful insights into the incidence and epidemiology of bacterial meningitis in Turkey. All the data presented in this study were gathered through study centers. This method (sentinel surveillance) is the appropriate way to collect data for common infectious diseases like influenza, but for rare diseases like meningococcal meningitis, we need nationwide study centers in Turkey where we may catch more cases through an active surveillance system.

It has been shown that introduction of conjugate vaccines can dramatically reduce meningitis disease incidence, if vaccines are administered to the target population with high vaccine coverage.1,14,37 Hib and PCV-13 vaccines are already available for infants starting from two months of age in the Turkish NIP and the meningococcal vaccine for Hajj pilgrims has already been switched to conjugated quadrivalent vaccine in order to decrease carriage of the microorganism by returning pilgrims. In this study we observed a drastic decreased of Hib meningitis in Turkish children since Hib vaccine has been introduced in NIP.

The epidemiology and etiology of bacterial meningitis may change over time and by regions in a way that cannot be predicted. In our study we showed that 51.6% of meningitis in seven Turkish regions in 1–18 y old children was caused by N. meningitidis. Although the number of Men B cases decreased in the last few years, serogroup B was still the second most common causative agent of meningococcal meningitis (26.1%) in Turkey over the entire study period (2005–2012).

As conjugated quadrivalent meningococcal ACWY vaccines as well as the recently licensed 1 meningococcal B vaccine38 are available, their use in 1–18 y old could dramatically reduce the burden of meningococcal disease in Turkey.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The study was supported by Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics (for 5 years) and by GlaxoSmithKline (for 2 years). The authors declare that they have no other conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Serdar Altinel MD PhD and Kathleen Jenks PhD, both employees of Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics, provided editorial support.

References

- 1.Li Y, Yin Z, Shao Z, Li M, Liang X, Sandhu HS, Hadler SC, Li J, Sun Y, Li J, et al.; Acute Meningitis and Encephalitis Syndrome Study Group. Population-based surveillance for bacterial meningitis in China, September 2006-December 2009. Emerg Infect Dis 2014; 20:61-9; PMID:24377388; http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2001.120375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim KS. Acute bacterial meningitis in infants and children. Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10:32-42; PMID:20129147; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70306-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feigin RD, Curter WB. Bacterial Meningitis Beyond The Neonatal Period. In: Feigin & Cherry's Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases edn. Edited by Feigin RD, Cherry JD, Harrison RE, Kaplan SL; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sáez-Llorens X, McCracken GH, Jr. Bacterial meningitis in children. Lancet 2003; 361:2139-48; PMID:12826449; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13693-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baraff LJ, Lee SI, Schriger DL. Outcomes of bacterial meningitis in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1993; 12:389-94; PMID:8327300; http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006454-199305000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grandgirard D, Leib SL. Strategies to prevent neuronal damage in paediatric bacterial meningitis. Curr Opin Pediatr 2006; 18:112-8; PMID:16601488; http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.mop.0000193292.09894.b7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edmond K, Clark A, Korczak VS, Sanderson C, Griffiths UK, Rudan I. Global and regional risk of disabling sequelae from bacterial meningitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10:317-28; PMID:20417414; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70048-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khowaja AR, Mohiuddin S, Cohen AL, Khalid A, Mehmood U, Naqvi F, Asad N, Pardhan K, Mulholland K, Hajjeh R, et al. Mortality and neurodevelopmental outcomes of acute bacterial meningitis in children aged <5 years in Pakistan. J Pediatr. 2013 Jul;163(1 Suppl):S86-S91.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agrawal S, Nadel S. Acute bacterial meningitis in infants and children: epidemiology and management. Paediatr Drugs 2011; 13:385-400; PMID:21999651; http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/11593340-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melegaro A, Edmunds WJ, Pebody R, Miller E, George R. The current burden of pneumococcal disease in England and Wales. J Infect 2006; 52:37-48; PMID:16368459; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2005.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pathan N, Faust SN, Levin M. Pathophysiology of meningococcal meningitis and septicaemia. Arch Dis Child 2003; 88:601-7; PMID:12818907; http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/adc.88.7.601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Outbreak news. Meningococcal disease, African meningitis belt, epidemic season 2006. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2006; 81:119-20; PMID:16673512 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenstein NE, Perkins BA, Stephens DS, Popovic T, Hughes JM. Meningococcal disease. N Engl J Med 2001; 344:1378-88; PMID:11333996; http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200105033441807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison LH. Prospects for vaccine prevention of meningococcal infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006; 19:142-64; PMID:16418528; http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CMR.19.1.142-164.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephens DS. Conquering the meningococcus. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2007; 31:3-14; PMID:17233633; http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00051.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison LH, Trotter CL, Ramsay ME. Global epidemiology of meningococcal disease. Vaccine 2009; 27(Suppl 2):B51-63; PMID:19477562; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.04.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taha MK, Achtman M, Alonso JM, Greenwood B, Ramsay M, Fox A, Gray S, Kaczmarski E. Serogroup W135 meningococcal disease in Hajj pilgrims. Lancet 2000; 356:2159; PMID:11191548; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03502-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan LK, Carlone GM, Borrow R. Advances in the development of vaccines against Neisseria meningitidis. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:1511-20; PMID:20410516; http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0906357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertherat E, Yada A, Djingarey MH, Koumare B. [First major epidemic caused by Neisseria meningitidis serogroup W135 in Africa?]. Med Trop (Mars). 2002;62(3):301-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berkley JA, Versteeg AC, Mwangi I, Lowe BS, Newton CR. Indicators of acute bacterial meningitis in children at a rural Kenyan district hospital. Pediatrics 2004; 114:e713-9; PMID:15574603; http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-0007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray SJ, Trotter CL, Ramsay ME, Guiver M, Fox AJ, Borrow R, Mallard RH, Kaczmarski EB; Meningococcal Reference Unit. Epidemiology of meningococcal disease in England and Wales 1993/94 to 2003/04: contribution and experiences of the Meningococcal Reference Unit. J Med Microbiol 2006; 55:887-96; PMID:16772416; http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.46288-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doganci L, Baysallar M, Saracli MA, Hascelik G, Pahsa A. Neisseria meningitidis W135, Turkey. Emerg Infect Dis 2004; 10:936-7; PMID:15200836; http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1005.030572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kilic A, Urwin R, Li H, Saracli MA, Stratton CW, Tang YW. Clonal spread of serogroup W135 meningococcal disease in Turkey. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44:222-4; PMID:16390974; http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.44.1.222-224.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceyhan M, Yildirim I, Balmer P, Borrow R, Dikici B, Turgut M, Kurt N, Aydogan A, Ecevit C, Anlar Y, et al. A prospective study of etiology of childhood acute bacterial meningitis, Turkey. Emerg Infect Dis 2008; 14:1089-96; PMID:18598630; http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1407.070938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taha MK. Simultaneous approach for nonculture PCR-based identification and serogroup prediction of Neisseria meningitidis. J Clin Microbiol 2000; 38:855-7; PMID:10655397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsolia MN, Theodoridou M, Tzanakaki G, Kalabalikis P, Urani E, Mostrou G, Pangalis A, Zafiropoulou A, Kassiou C, Kafetzis DA, et al. The evolving epidemiology of invasive meningococcal disease: a two-year prospective, population-based study in children in the area of Athens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2003; 36:87-94; PMID:12727371; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00083-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ceyhan M, Ozsurekci Y, Gurler N, Ozkan S, Sensoy G, Belet N, Hacimustafaoglu M, Celebi S, Keser M, Dinleyici EC, et al. Serotype Distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae Causing Parapneumonic Empyema in Turkey. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013 Jul;20(7):972-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray LD, Fedorko DP. Laboratory diagnosis of bacterial meningitis. Clin Microbiol Rev 1992; 5:130-45; PMID:1576585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tzanakaki G, Tsopanomichalou M, Kesanopoulos K, Matzourani R, Sioumala M, Tabaki A, Kremastinou J. Simultaneous single-tube PCR assay for the detection of Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae type b and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005 May;11(5):386-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lukšić I, Mulić R, Falconer R, Orban M, Sidhu S, Rudan I. Estimating global and regional morbidity from acute bacterial meningitis in children: assessment of the evidence. Croat Med J 2013; 54:510-8; PMID:24382845; http://dx.doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2013.54.510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snape MD, Pollard AJ. Meningococcal polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccines. Lancet Infect Dis 2005; 5:21-30; PMID:15620558; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01251-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lind I, Berthelsen L. Epidemiology of meningococcal disease in Denmark 1974-1999: contribution of the laboratory surveillance system. Epidemiol Infect 2005; 133:205-15; PMID:15816145; http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0950268804003413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenstein NE, Perkins BA, Stephens DS, Lefkowitz L, Cartter ML, Danila R, Cieslak P, Shutt KA, Popovic T, Schuchat A, et al. The changing epidemiology of meningococcal disease in the United States, 1992-1996. J Infect Dis 1999; 180:1894-901; PMID:10558946; http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/315158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maiden MC, Stuart JM, UK Meningococcal Carraige Group. Carriage of serogroup C meningococci 1 year after meningococcal C conjugate polysaccharide vaccination. Lancet 2002; 359:1829-31; PMID:12044380; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08679-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ceyhan M, Celik M, Demir ET, Gurbuz V, Aycan AE, Unal S. Acquisition of meningococcal serogroup W-135 carriage in Turkish Hajj pilgrims who had received the quadrivalent meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2013; 20:66-8; PMID:23136117; http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CVI.00314-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dinleyici EC, Ceyhan M. The dynamic and changing epidemiology of meningococcal disease at the country-based level: the experience in Turkey. Expert Rev Vaccines 2012; 11:515-8; PMID:22827237; http://dx.doi.org/10.1586/erv.12.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pellegrino P, Carnovale C, Perrone V, Salvati D, Gentili M, Brusadelli T, Antoniazzi S, Pozzi M, Radice S, Clementi E. Epidemiological analysis on two decades of hospitalisations for meningitis in the United States. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gasparini R, Amicizia D, Domnich A, Lai PL, Panatto D. Neisseria meningitidis B vaccines: recent advances and possible immunization policies. Expert Rev Vaccines 2014; 13:345-64; PMID:24476428; http://dx.doi.org/10.1586/14760584.2014.880341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]