Abstract

Participation in the federally subsidized school breakfast program often falls well below its lunchtime counterpart. To increase take-up, many districts have implemented Breakfast in the Classroom (BIC), offering breakfast directly to students at the start of the school day. Beyond increasing participation, advocates claim BIC improves academic performance, attendance, and engagement. Others caution BIC has deleterious effects on child weight. We use the implementation of BIC in New York City (NYC) to estimate its impact on meals program participation, body mass index (BMI), achievement, and attendance. While we find large effects on participation, our findings provide no evidence of hoped-for gains in academic performance, or of feared increases in obesity. The policy case for BIC will depend upon reductions in hunger and food insecurity for disadvantaged children, or its longer-term effects.

INTRODUCTION

The federal School Breakfast Program (SBP) has subsidized breakfasts for needy children since 1966, with the aims of reducing food insecurity, improving nutrition, and facilitating learning (Bhattacharya, Currie, & Haider, 2006; Frisvold, 2015; Millimet, Tchernis, & Husain, 2010; Poppendieck, 2010). Participation in the SBP, however, typically falls well below that of its lunchtime counterpart (Bartfeld & Kim, 2010; Basch, 2011; Dahl & Scholz, 2011; Schanzenbach & Zaki, 2014). In New York City, for example, less than a third of all students take a breakfast each day, even though it has been offered free to all students since 2003 and roughly three in four students live in low-income households (Leos-Urbel et al., 2013).1

To increase participation in the SBP, a number of school districts have adopted Breakfast in the Classroom (BIC), a program that offers free breakfast to students in the classroom at the start of the school day, rather than providing it in the cafeteria before school. The intent is to reach students unable or unwilling to arrive early to school, and to reduce stigma associated with visiting the cafeteria before school for a subsidized meal. New York City (NYC), the largest provider of school meals in the country and a national leader in school food policy, began implementing BIC in 2007. Today the program is offered in nearly 300 of the city’s 1,700 public schools, with more than 30,000 BIC breakfasts served per day.2

Advocates argue that moving breakfast from the cafeteria to the classroom provides myriad benefits, including improved academic performance, attendance, and engagement, in addition to reducing hunger and food insecurity among disadvantaged children. Indeed, there is evidence that the consumption, timing, and nutritional quality of breakfast can affect cognitive performance (e.g., Hoyland, Dye, & Lawton, 2009; Rampersaud et al., 2005; Wesnes et al., 2003). While there has been less work evaluating BIC in particular, at least one study found that moving breakfast to the classroom substantially improved math and reading performance (Imberman & Kugler, 2014).3 At the same time, others have raised concerns that BIC will contribute to weight gain and obesity, as participants consume more daily calories or less healthy food than they otherwise would. In NYC, the Bloomberg administration temporarily halted the expansion of BIC when an internal study found BIC students were more likely to eat two breakfasts, one at home and another during school (Van Wye et al., 2013).4 There is, however, scant research available to guide policymakers in resolving these conflicting claims, and virtually no evidence on the impact of BIC on student weight.

In this paper, we use the staggered implementation of BIC in NYC together with longitudinal data on student height, weight, achievement, and attendance to estimate the program’s impact on body mass index (BMI), obesity, academic performance, and attendance. We begin by investigating whether BIC had a significant impact on schools’ average daily participation in the breakfast and lunch programs. Then, we use longitudinal student data to estimate the impact of BIC on BMI and other outcomes. These analyses use a difference-in-difference design, contrasting observationally similar students in schools that did and did not adopt BIC, before and after implementation. We also estimate impacts through an event study specification, using a series of indicators identifying years before and after BIC adoption to capture potential differences in outcome trajectories prior to adoption.5 Importantly, all estimated effects are interpreted as intent-to-treat, since the treatment here is the offer of BIC to all or some students in a school. As is true in most studies, we do not observe individual student meal consumption or classroom level participation in BIC (and some schools partially implemented the program, as explained later). Rather, treatment status is measured using ordered categories representing the extent of BIC implementation at the school level, or alternately, the amount of time an individual student has been offered BIC at their school. Intent-to-treat effects are of interest to policymakers weighing the adoption of BIC, given schools’ (and students’) discretion to participate or not.

We find that NYC schools offering BIC saw a substantial increase in school breakfast participation with no spillover effects on lunch participation. There is no evidence BIC increased BMI or the incidence of obesity among affected students. We find small and statistically imprecise effects on reading and math achievement in grades 4 through 8, in sharp contrast with Imberman and Kugler (2014), and no effects on attendance rates, in contrast with Dotter (2012). While our data do not permit us to examine impacts on individual student eating behaviors, our findings are consistent with recent experimental evidence showing BIC has, at best, small effects on net breakfast consumption and nutrition (Schanzenbach & Zaki, 2014).

BACKGROUND

The Effects of School Meals on Health and Academic Achievement

There is evidence that the availability and quality of school meals programs can affect the nutritional intake and academic outcomes of participating students. For example, in a study of the SBP, Bhattacharya, Currie, and Haider (2006) used detailed survey data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III to investigate how access to the SBP affected children’s breakfast consumption and nutrient intake. They found no impact of the SBP on total calories consumed or the likelihood of eating breakfast, but found large effects on the nutritional quality of breakfasts eaten, with fewer calories from fat, and higher serum levels of vitamins C, E, and folate. Schanzenbach (2009) examined the body weight of students participating in the school lunch program and found that children eating school lunches were more likely to be obese than those bringing their own lunch, a finding she attributed to higher caloric intake among students taking school lunches. A study by Millimet, Tchernis, and Husain (2010) corroborated this finding for school lunches, but—consistent with Bhattacharya, Currie, and Haider (2006)—found that SBP participation was associated with lower rates of obesity.

Evidence on the causal impact of school meals on educational outcomes is more mixed (Hoyland, Dye, & Lawton, 2009). In one study of the long-run effects of the national school lunch program, Hinrichs (2010) found sizable effects on the educational attainment of adults who were exposed to the program early in life. Frisvold (2015) likewise found that state mandates to offer breakfast in high-poverty schools had a positive effect on achievement. On the other hand, using administrative data from Chile, McEwan (2013) found no short-run effects on test scores, school attendance, and grade repetition of providing free high-calorie meals to poor children. Similarly, Dunifon and Kowaleski-Jones (2003) found little association between school lunch program participation in the United States and achievement after accounting for selection into the program.6 It is important to point out that even where positive effects of school meals programs are found, it is difficult to separate their direct effect (through meals consumption) from indirect effects (via increased attendance or improved behavior, for example; see Hoyland, Dye, & Lawton, 2009; Adolphus, Lawton, & Dye, 2013).

A clever study examining schools’ responses to test-based accountability in Virginia found evidence that schools under accountability pressure increased the caloric content of their meals on test days and saw larger increases in passing rates as a result (Figlio & Winicki, 2005). Consistent with this type of short-run effect, Imberman and Kugler (2014) found the introduction of BIC into a large urban school district had large positive effects on reading and math achievement, even when the program was implemented a short time before the test. (We describe this study in greater detail in the next section.)

Experimental studies have also found that the consumption and quality of breakfast can have at least a short-run effect on child cognitive performance.7 For example, a study in the United Kingdom randomly assigned 10-year-old students to different breakfast regimens at home and found students receiving a higher energy breakfast scored higher on tests of creativity and number checking (Wyon et al., 1997). They were also less likely to report feeling bad or hungry. Wesnes et al. (2003) randomly assigned students to receive one of four types of breakfast on successive days (one of two types of cereal, a glucose drink, or no breakfast) and found that students eating a cereal breakfast performed better on a series of tests of attention and memory over the course of the morning. Simeon and Grantham-McGregor (1989) conducted a small experiment in which undernourished children in the West Indies were randomly assigned to receive a breakfast or a cup of tea on alternate days. After consuming breakfast, students performed better on cognitive tests of arithmetic and problem solving than when drinking only tea.

Relevant to BIC, one study we identified found that when breakfast is consumed relates to its effects on cognitive performance. In a randomized control trial, Vaisman et al. (1996) found that 11- to 13-year-old students who ate a regular breakfast before school (two hours before testing) performed no better than a control group on tests of cognitive functioning. However, students who ate a cereal and milk breakfast in class 30 minutes before testing performed significantly better.

Breakfast in the Classroom

BIC alters the traditional SBP by offering a free breakfast in class at the start of the school day, rather than in the cafeteria before school hours (FRAC, 2012). The intent is to increase breakfast participation among students who are unable or unwilling to arrive early to school, and to reduce stigma associated with visiting the cafeteria before school for a subsidized meal. BIC advocates have argued the program also provides an opportunity to integrate nutrition into the curriculum, as teachers can use the time to teach good eating habits. Proponents tout the social aspects of the program as well, citing the benefits of communal eating.8

BIC breakfasts are typically offered during the first 10 to 20 minutes of class. Meals are often bagged the prior evening by school food staff, placed into insulated containers, and refrigerated overnight. They are then delivered to classrooms in the morning, or distributed to students as they arrive (Grab and Go). Because breakfasts are typically assembled the night before, BIC menus generally differ from those prepared in the cafeteria. Specifically, BIC meals usually consist of cold, prepacked items such as cereal, fresh fruit, or bagels. Cafeteria breakfasts, on the other hand, include hot meals such as pancakes or egg omelets.9 Though they may differ in menu offerings, BIC meals are required to meet the same federal nutritional guidelines as cafeteria breakfasts. For federal reimbursement purposes, they are accounted for in the same way as traditional cafeteria breakfasts.

The Food Research and Action Center (FRAC), a national advocate for the SBP in general and BIC in particular, credits BIC for high rates of SBP participation in urban school districts such as Detroit, Houston, Newark, San Antonio, Washington, DC, and Providence in 2012. There have been few studies, however, on BIC’s effects on breakfast participation, academic or behavioral outcomes, or weight. One evaluation of a 2003/04 BIC pilot in upstate New York found SBP participation doubled after implementation of the program, and found modest improvements in attendance, behavior, and tardiness (Murphy, Drake, & Weineke, 2005). The study, however, lacked a control group and involved only a small number of schools. Anzman-Frasca et al. (2015) examined the effects of BIC on SBP participation in a large urban school district and estimated that BIC increased participation by 30 percentage points, relative to matched non-BIC schools. Similarly, in reanalyzing data from an earlier U.S. Department of Agriculture experiment, Schanzenbach and Zaki (2014) found that BIC had a large positive effect on SBP participation and increased the likelihood that students ate a “nutritionally substantive” breakfast. They found the effect of BIC on participation was considerably larger than the offer of free breakfast alone.

Imberman and Kugler (2014) provide strong quasi-experimental evidence on the intent-to-treat effects of BIC on achievement. That study examined the impact of BIC on math and reading scores in 5th grade, and attendance and report card marks in grades 1 through 5. Their setting was an urban district that—like NYC—had previously offered free breakfast to all students, regardless of subsidy eligibility (Leos-Urbel et al., 2013). The district implemented BIC in 85 schools over a period of 11 weeks in 2009/10, which enabled the authors to contrast outcomes in early adopter schools (those implementing BIC before the test) with those in late adopting schools (implementing after the test). They found substantial effects of BIC on reading and math achievement (0.10 standard deviations (SD)), with larger effects for initially low-achieving students (0.13 to 0.14 SD), Hispanics (0.14 to 0.15 SD), and low-BMI students (0.26 SD). As many students already participated in the SBP, the treatment effect of BIC on the treated in this district was potentially much higher. They found no impact of BIC on attendance rates or report card grades.

Interestingly, the achievement effects found in Imberman and Kugler did not vary with the amount of time students had been offered BIC. Thus, even schools that adopted BIC as little as one week prior to testing experienced gains in test performance. While seemingly implausible at first, their finding mirrors Figlio and Winicki (2005), who found that increasing caloric content of lunch on test day can improve test performance. It also aligns with the experimental evidence described earlier on the short-run effects of breakfast consumption and content on cognitive performance. Imberman and Kugler’s finding of no impact on grades but a large impact on test scores supports a short-run caloric effect and lack of a sustained, long-run impact on achievement, but the study’s short duration makes it difficult to rule out long-run effects.

Like Imberman and Kugler (2014), an unpublished study by Dotter (2012) used the introduction of BIC in San Diego over a four-year period to estimate its effects on achievement in grades 2 through 6, attendance, and classroom behavior. In contrast to NYC and the district in Imberman and Kugler (2014), San Diego had only previously offered universal-free breakfasts in schools with Provision 2 status under the National School Lunch Act (UFM schools).10 All others offered breakfast free or at a reduced rate to subsidy-eligible students and at full price to other students. BIC in San Diego thus coincided with a shift to universal-free breakfast in schools that were not already UFM, making it difficult to disentangle the BIC and price effects. Like Imberman and Kugler, Dotter found large intent-to-treat effects of BIC on achievement (0.11 SD in reading and 0.15 SD in math), but only in schools that did not already offer free breakfast to all students. Thus, the effect should be interpreted as the combined effect of BIC and free breakfast. He found no effect on attendance, but large positive effects on teacher-reported classroom behavior, such as exhibiting “respect for people and property.”

Finally, a third quasi-experimental study by Anzman-Frasca et al. (2015) examined the impact of BIC on meals program participation and achievement in a large urban school district in 2012/13. They found a large effect of the program on SBP participation (noted above), but unlike the other two studies described here, found no impact on student achievement in second to sixth grade. Anzman-Frasca et al. (2015) did find a positive, statistically significant effect of BIC on attendance, but the effect size was very small.

These three studies offer strong evidence on the academic impacts of BIC, and go far beyond what was previously available. However, they have several limitations. First, none provided evidence of the program’s effect on student weight, an important outstanding question in the literature. Second, two of the three relied on relatively small samples of elementary schools. Imberman and Kugler’s main estimates use fifth graders in approximately 85 treatment and 19 control schools; Dotter looked at a broader range of grade levels, but a smaller number of schools (45 treatment and 22 control). His sample of non-UFM schools—where the only significant effects were found—was smaller (19 treatment and 16 control). Third, only Dotter is able to say much about long-run effects, up to four years after the first BIC implementation. Imberman and Kugler provide a clean estimate of the short-run impact of BIC, but their results may say more about caloric intake and the short-term malleability of test performance than about the long-run consequences of adjusting children’s eating habits. Our analysis improves on prior work by incorporating annual student-level measures of BMI and a larger sample of students and BIC schools at both the elementary and middle school level.11

Three studies that we are aware of have looked at the relationship between BIC and calorie consumption or weight, although only one has a design that can support causal claims. Baxter et al. (2010) collected cross-sectional data on BMI, breakfast program participation, and energy intake (from researcher observations) for a sample of fourth grade students in 17 schools, seven of which had adopted BIC. They found children in BIC consumed more calories at breakfast and had higher BMIs, on average, than children eating breakfast in the cafeteria. Van Wye et al. (2013) surveyed students in nine BIC and seven comparison schools in NYC and found students offered BIC were more likely to eat more than once in the morning, consuming 95 more calories, on average, than students in schools not offering BIC. Access to student-specific data on food consumption is an obvious advantage of these studies. However, both were correlational with a small number of schools that did not address selection into BIC. Schanzenbach and Zaki (2014) provide stronger evidence of the program’s effects on breakfast consumption and obesity by reanalyzing data from an experiment conducted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in the early 2000s (Bernstein et al., 2004). In the original experiment, treatment schools offered universal free breakfast and could choose to serve it in the cafeteria or in the classroom. In a comparison of BIC and control schools that did not offer free breakfast, the authors found large effects of BIC on participation, and a five percentage point increase in the likelihood of eating more than one breakfast, but modest effects on breakfast consumption, and no effect on BMI or nutrition. They conclude that—for most students—BIC changed the location and timing of breakfast rather than the propensity to consume it. Not surprisingly in light of this, they find BIC had no impact on achievement or behavior. While randomization of free breakfast is an important feature of this study, it is worth noting the decision to offer BIC was not random, making the comparison of BIC and other treated schools (offering free breakfast only) nonexperimental. Further, the number of BIC schools (18) was small relative to the cafeteria group (61). The community context for schools in the USDA study was also quite different from ours.12 Thus, there are open questions about the efficacy of BIC in schools offering universal free breakfast in the cafeteria—the context increasingly relevant for urban school districts nationwide.

DATA

Data Sources, Outcomes, and Sample Definitions

We draw on four primary data sources, all provided by the New York City Department of Education (NYCDOE) and its Office of School Food. The first is a database of BIC participation that includes program start dates for schools that ever adopted BIC, and information about the extent of coverage in the school (e.g., grades served and the number of BIC and total classrooms). The second is longitudinal school-level data on breakfast and lunch participation for all regular public schools that served elementary grades, middle grades, or both between 2001/02 and 2011/12. These data provide annual counts of meals served, average daily attendance (ADA), and Provision 2 (UFM) status, and include 1,000 to 1,100 schools enrolling 713,000 to 730,000 students, depending on the year. The third is administrative data for the universe of students in NYC public schools between 2006/07 and 2011/12, including demographics, educational needs and program participation, standardized test scores, and attendance rates. Finally, the fourth is annual student height and weight measurements collected through the city’s Fitnessgram program; these are used to compute BMI and indicators of obesity, as described below. We exclude high schools, private, charter, prekindergarten, alternative, and other special schools and programs.13

The student-level administrative data track students longitudinally as they progress through school. These data include school of record, state test scores in English Language Arts (ELA) and mathematics (both in grades 3 through 8 only), gender, race/ethnicity, age, household income eligibility for free or reduced price meals, recent immigrant status, days in attendance, days enrolled, and participation in other educational programs (e.g., special education and English language learner (ELL)). We standardized ELA and math scores within grade, subject, and testing year. Grade 3 test scores are used only as lagged outcomes for students in 4th grade. We calculated student attendance rates as the number of days present as a percentage of days enrolled.

NYC schools have conducted the Fitnessgram since 2005/06 as part of the district’s standards-based physical education program.14 NYC’s Fitnessgram program requires all schools to collect students’ height and weight annually, and to assess students’ aerobic fitness, muscle strength, endurance, and flexibility. At the end of the year, students receive a report that summarizes their performance and suggests ways for them to reach their “Healthy Fitness Zone,” targets for better health based on their age and gender. While school coverage rates were lower in the early years of the Fitnessgram, by 2012 nearly 1,700 schools were participating each year, providing data on more than 860,000 students in all grades.

Though there is an ongoing conversation in the public health literature on the best measure of adiposity in children (e.g., Cole et al., 2005; Mooney, Baecker, & Rundle, 2013), BMI is the most common. From the Fitnessgram we used students’ weight (in pounds) and height (in inches) to compute the standard BMI measure (weight/height2) × 703. Biologically implausible values—defined as more than 4 SD below or 5 SD above the mean for the students’ gender and age in months—were set to missing (fewer than 20 cases per year). We classified children as obese if their BMI was at or above the 95th percentile for their gender and age in months, based on CDC growth charts.15 In our analyses of student weight, we use two outcome measures: BMI standardized by gender and age, using all students in the New York City Fitnessgram data (z-BMI), and a 0 to 1 indicator for BMI above the CDC obesity threshold.

Our analytic samples for BMI/obesity, achievement, and attendance overlap, but differ in two key ways. First, the included grade levels vary, depending on data availability. Models for BMI and attendance include students in grades K through 8, while the models for achievement include only grades 4 through 8. Second, the BMI sample excludes students in school years where Fitnessgram participation was lower than 50 percent. These students were not excluded from the other models. In allowing these analytic samples to differ, we make full use of available data. (The Appendix reports estimates from models estimated using a fixed sample of students. The results are very similar.)16

BIC Adoption in New York City

Figure 1 shows the cumulative number of NYC schools that adopted BIC, by month, between 2007/08 and 2011/12. (The figure is limited to public schools enrolling grades K through 8, and excludes private and charter schools.) The largest number of adoptions occurred in early 2010/11, although a significant number of schools began offering BIC in 2008/09 and 2009/10. By the end of 2011/12, 284 elementary and middle schools had adopted the program, with an average daily participation of more than 30,000 students. It is worth noting that some schools adopted BIC in the middle of the school year, suggesting its full effect on annually measured outcomes may not be observed until the following year.

Figure 1. Cumulative BIC Adoptions by Month, New York City.

Notes: Reflects all schools adopting BIC prior to June 30, 2012 that offered BIC to any of the grades K through 8. Only regular public schools are included; private, charter, alternative, and special education (District 75) schools are excluded, as are suspension or other special programs. As of April 2012, there were 163 schools offering BIC with <25 percent coverage; 80 schools offering BIC with ≥25 percent coverage (but not full school); and 41 schools offering BIC schoolwide.

Not every school adopted BIC schoolwide, which has implications for how we define “treatment.” In some cases, BIC was offered only to specific grades or a subset of classrooms within the school.17 Lacking data linking specific students or classrooms to BIC, we used information on the approximate number of BIC classrooms, participating grades (where available), and school grade span to create three ordered categories of program coverage in a school.18 The first includes schools offering BIC in fewer than 25 percent of classrooms, which may include schools piloting the program with a relatively small number of students. The second category consists of schools offering BIC in 25 percent or more classrooms, but not schoolwide. Finally, the third category includes schools reporting they offered BIC schoolwide (“full BIC”). The bars in Figure 1 show the cumulative number of schools that adopted BIC in each category. The majority of schools are in the first group, but by the end of 2011/12, 80 elementary and middle schools offered BIC to at least 25 percent of classrooms, and 41 offered it schoolwide.

While data from the Office of School Food included some information about specific grades and the percentage of classrooms in each school offering BIC, we were not confident enough in the precision of these data to use them as our primary measure of treatment exposure. This led us to adopt the broader categories described here. Results from models that use as-reported grade-specific treatment indicators or the (continuous) percentage of classrooms offering BIC do not yield different results, and are available from the authors upon request.

Table 1 reports baseline mean characteristics for schools that never (or ever) adopted BIC; the latter are split into the three categories of coverage defined above. On a number of dimensions, BIC schools were more disadvantaged than those that never adopted the program. For example, full BIC schools enrolled a greater percentage of students eligible for free meals (80.6 versus 67.3 percent in “never BIC” schools) and had higher concentrations of black, Hispanic, and ELL students. Standardized test scores were lower, on average, in full BIC schools, both in reading (−0.28 SD) and in math (−0.31 SD), and were comparably low in schools that adopted BIC in 25 percent or more classrooms, but not schoolwide. Schools in all five boroughs adopted BIC, though BIC schools were overrepresented in the Bronx. Average daily participation in the SBP was comparable in schools that adopted BIC versus those that did not, despite higher rates of eligibility for subsidized meals. Finally, students in BIC schools had a higher BMI, on average, at baseline than those attending non-BIC schools, especially in schools with greater BIC coverage. Roughly one in four students were obese in schools that adopted BIC schoolwide, compared with roughly one in five in non-BIC schools.

Table 1.

Mean school characteristics by BIC treatment status, baseline (2006/07).

| Never BIC | Ever BIC (<25%) |

Ever BIC (>25% but not full) |

Ever BIC (full school) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breakfast participation rate | 24.5 | 22.9 | 23.5 | 24.6 |

| Lunch participation rate | 76.5 | 77.6 | 82.7 | 82.4 |

| BMI z-score | 0.008 | −0.006 | 0.095 | 0.160 |

| Percent obese | 21.1 | 20.5 | 21.9 | 26.2 |

| Reading z-score (grades 3–8) | 0.016 | −0.036 | −0.247 | −0.276 |

| Math z-score (grades 3–8) | 0.001 | −0.064 | −0.285 | −0.307 |

| Attendance rate | 92.1 | 91.8 | 89.7 | 91.2 |

| Percent eligible for free lunch | 67.3 | 68.9 | 81.8 | 80.6 |

| Percent ELL | 11.7 | 12.8 | 11.9 | 14.5 |

| Percent special education | 13.9 | 14.1 | 14.6 | 17.1 |

| Percent Asian | 12.4 | 11.6 | 3.1 | 4.8 |

| Percent black | 33.5 | 34.8 | 43.4 | 34.6 |

| Percent Hispanic | 38.5 | 38.5 | 49.4 | 55.9 |

| Percent white | 14.7 | 14.2 | 3.2 | 3.5 |

| Percent male | 50.7 | 51.4 | 50.1 | 50.0 |

| Percent enrollment grades K–5 | 60.1 | 57.2 | 59.5 | 65.1 |

| Percent in Brooklyn | 33.2 | 32.1 | 30.8 | 7.9 |

| Percent in Manhattan | 17.3 | 17.0 | 17.9 | 42.1 |

| Percent in Queens | 24.3 | 23.0 | 6.4 | 10.5 |

| Percent in Staten Island | 4.8 | 7.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Percent in Bronx | 20.3 | 20.6 | 44.9 | 39.5 |

| Percent UFM school | 45.1 | 40.1 | 45.5 | 45.9 |

| School starting time | 8:20 a.m. | 8:18 a.m. | 8:22 a.m. | 8:19 a.m. |

| Total enrollment | 657 | 754 | 695 | 660 |

| N (observed in 2007) | 807 | 165 | 78 | 38 |

Notes: Only regular public schools serving any of the elementary and middle grades are included in the above. All means are for the 2006/07 academic year, and thus are prior to any school’s adoption of BIC. “Never BIC” refers to schools that had not adopted BIC as of June 30, 2012. “Ever BIC” refers to any school that adopted BIC prior to June 30, 2012. Schools that ever adopted BIC are divided into three categories: (1) those that offered BIC to fewer than 25 percent of all classrooms; (2) those that offered BIC to 25 percent or more of classrooms, but did not offer it schoolwide; (3) those that reported offering BIC schoolwide. In the few cases where BIC coverage changed over time, we classified schools according to their greatest extent of coverage.

Empirical Strategy

Our empirical approach uses difference-in-differences regressions at the school or student level (depending on the outcome), which compare outcomes in schools that did and did not adopt BIC, before and after implementation. Included covariates and school-fixed effects account for nonrandom selection of schools into the program on the basis of observed characteristics or time-invariant factors correlated with the outcome of interest. We address the possibility that BIC and non-BIC schools were on different trajectories prior to adoption of BIC through event study models, described below and shown graphically in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2. Estimated Impact of BIC on Annual Breakfast and Lunch Participation Rates: Elementary and Middle Schools.

Notes: Event study coefficients from school-level regressions. Meals program participation is measured as average daily meals served divided by ADA. All models include school and year effects. Covariates include total school enrollment, percent ELL, percent receiving special education services, percent of students by race/ethnicity, percent female, percent eligible for free meals, and percent eligible for reduced price meals. Separate indicator variables are included for three categories of BIC schools: (1) those that offered BIC to fewer than 25 percent of all classrooms; (2) those that offered BIC to 25 percent or more of classrooms, but did not offer it schoolwide; (3) those that reported offering BIC schoolwide. These category variables are interacted with indicators for years before and after BIC adoption. Only results for categories (2) and (3) are pictured. Dashed and dotted lines represent a robust 95 percent confidence interval.

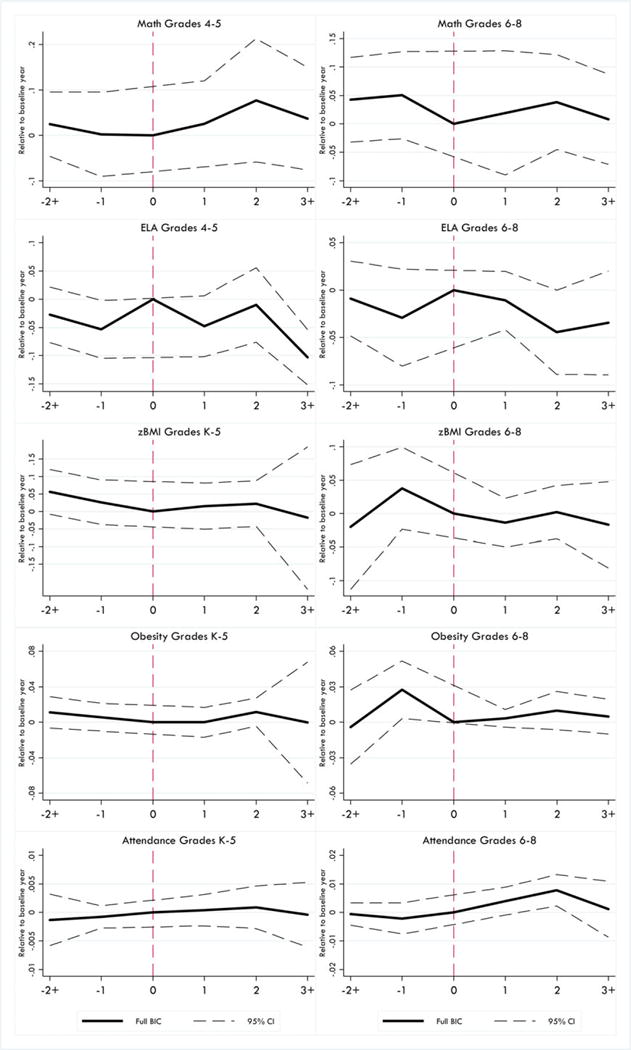

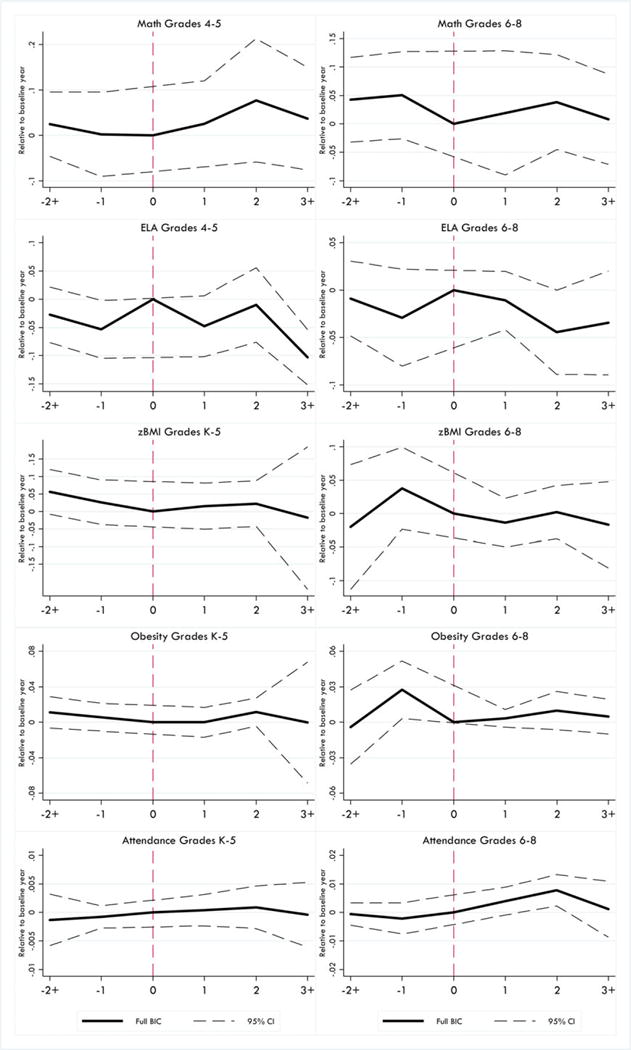

Figure 3. Estimated Impact of BIC by Year, Event Study Regressions.

Notes: Baseline year zero is the year prior to BIC adoption. For clarity of presentation only results for the second category of BIC coverage are shown (>25 percent of classrooms, but not school wide). Dashed lines represent a robust confidence interval.

The impact of BIC on meals program participation is estimated using annual data at the school level. The following model is estimated for breakfast and lunch participation for all schools combined and separately for elementary and middle schools:

| (1) |

In equation (1), the dependent variable is the average daily participation rate for meal m (breakfast or lunch) in school s and year t, defined as the average number of m meals served per school day (ADPm) divided by average daily attendance (ADA) and multiplied by 100. This can be interpreted as the percentage of students in attendance who take a meal m on an average day in school s in year t. BICst is a vector of indicators corresponding to the three-ordered categories of BIC coverage, equal to one if school s had adopted BIC at that level of coverage prior to the end of school year t (and zero otherwise). γs and αt are school and year effects, respectively, and Wst is a vector of school-level covariates, including total enrollment, percent female, percent by race/ethnicity, percent ELL, percent in special education, and percent eligible for free or reduced price meals. vst is an error term, and standard errors are adjusted for clustering by school. In alternative specifications of equation (1) shown in the Appendix, we add school-specific linear time trends to allow for differential trends over time in the outcomes.19

The intent-to-treat impact of BIC on student outcomes is estimated using data at the student level, again with separate models for elementary and middle school students, given prior literature that suggests the impact of school meals programs may vary by age, for both biological and behavioral reasons (e.g., stigma). Each model takes the following form for outcome Yigst (BMI, obesity, math/reading score, and attendance) for student i in grade g, school s, and year t:

| (2) |

BICst, γs, and αt are defined in the same manner as in equation (1), θg is a grade-level effect (interacted with the year effects in the achievement models), and Xit is a vector of student covariates potentially related to both the outcome and the adoption of BIC in school s. These include eligibility for free or reduced price meals, race and ethnicity, limited English proficiency, special education status, age in months (as of the date of BMI measurement and in the Fitnessgram models only), and lagged math or reading scores (in the math and reading models, respectively).20 uit is a student-year error term, and standard errors are adjusted for clustering by school. As before, BICst is defined using separate indicators for the three-ordered categories of coverage. In a second set of specifications, we allow the effect of BIC to vary by the cumulative number of days, in hundreds, that an individual student has attended a school offering BIC prior to the date their outcome was measured in year t.21 Note that this treatment variable can vary at the student level within school.

To test the identifying assumption that outcomes in BIC and non-BIC schools were on similar trajectories prior to adoption of the program, we estimate “event study” versions of models equations (1) and (2). In these regression models, we replace the BIC treatment variables with a set of indicators corresponding to specific years before and after BIC adoption, interacted with the BIC treatment variables. (The reference period for BIC schools is the first year of the program.) All other covariates from equations (1) and (2) are included in these models. Any significant differences in mean outcomes that we observe in the pretreatment period could reflect differential trends in BIC schools prior to adoption of the program. Differences in mean outcomes in the posttreatment period can also be used to test for differential effects over time (as in Dotter, 2012).

RESULTS

The Impact of BIC on School Meals Program Participation

Table 2 reports estimates of model (1) for the impact of BIC on average daily school breakfast and lunch program participation. Each column and panel in this table represents a separate regression, for the given meal type (breakfast or lunch) and school sample (elementary, middle, or all). Coefficients and standard errors are reported for the postadoption period for each of the three BIC coverage levels. Again, all models include school- and year-fixed effects, and school-level covariates.

Table 2.

Impact of BIC adoption on meals program participation, 2001/02.

| All schools | Elementary | Middle | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breakfast | |||

| Post-BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | 0.044*** (0.006) |

0.045*** (0.007) |

0.042*** (0.011) |

| Post-BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | 0.195*** (0.018) |

0.197*** (0.021) |

0.226*** (0.040) |

| Post-BIC adoption: full school | 0.302*** (0.032) |

0.333*** (0.043) |

0.336*** (0.032) |

| Lunch | |||

| Post-BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | 0.006 (0.007) |

0.009 (0.006) |

−0.009 (0.017) |

| Post-BIC adoption: School with >25% coverage, not full | −0.008 (0.008) |

0.011 (0.007) |

−0.036* (0.018) |

| Post-BIC adoption: full school | −0.005 (0.018) |

−0.001 (0.018) |

0.045 (0.048) |

| N—breakfast (school × year) | 12,407 | 7,833 | 2,598 |

| Mean breakfast participation pre-2008 | 0.201 | 0.236 | 0.120 |

| N—lunch (school × year) | 12,062 | 7,518 | 2,565 |

| Mean lunch participation 2008 | 0.732 | 0.813 | 0.629 |

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses, robust to clustering at the school level (***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05). Meals program participation is measured as the average daily breakfasts or lunches served divided by ADA. All models include school and year effects. Covariates include total school enrollment, percent Limited English proficient (LEP), percent receiving special education services, percent of students by race/ethnicity, percent female, percent eligible for free meals, and percent eligible for reduced price meals. Schools that ever adopted BIC are divided into three categories: (1) those that offered BIC to fewer than 25 percent of all classrooms; (2) those that offered BIC to 25 percent or more of classrooms, but did not offer it schoolwide; and (3) those that reported offering BIC schoolwide.

The point estimates in Table 2 show a large increase in breakfast program participation in schools offering BIC, with no corresponding change in lunch participation. As expected, we observe larger effects on participation where BIC coverage is greater. Across all schools serving elementary and middle grades, we find BIC increased SBP participation rates by 4.4 percentage points, on average, when BIC is offered in fewer than 25 percent of classrooms. On a baseline rate of 20.1, this represents an increase of 22 percent. When BIC is offered in 25 percent or more classes but not schoolwide, the increase in participation is 19.5 points—a near doubling. Finally, in schools reporting that they offered BIC schoolwide, we observe a 30.2 point increase in the SBP participation rate. Point estimates from separate elementary and middle school regressions are comparable, although the effect in middle school is proportionately larger, given a lower baseline rate (12 percent versus 23.6 in elementary schools).22 All coefficient estimates for breakfast program participation effects are statistically significant at the 0.01 level or better. Differences by program coverage provide some empirical support for our three-tiered classifications of BIC coverage, as well as a strong “first stage” effect of BIC on program take-up that would be needed if BIC were to have an effect on other student-level outcomes.23

In contrast, we find that offering BIC had no significant impact on lunch program participation. The coefficient estimates for lunch participation in Table 2 are small—usually less than one percentage point—and with the exception of one case, statistically insignificant. (We find a small negative effect of 3.6 points on lunch participation in middle schools with 25 percent or more coverage, on a baseline of 62.9 percent participation.) Taken together, there is little evidence to suggest BIC crowded out lunch program participation or encouraged greater participation (say, by reducing stigma associated with subsidized meals).

The difference in difference estimates are valid as causal effects only if BIC and non-BIC schools were experiencing similar trends in meals program participation prior to the adoption of BIC. In Figure 2, we show coefficients from event study regression models, in which separate indicator variables are included for BIC schools in years prior to and following BIC adoption. (Reference year zero is the year prior to adoption.) For clarity, the figure shows the coefficients and confidence interval bounds for the two most intensive BIC categories (more than 25 percent BIC and schoolwide). We observe virtually no trend in regression-adjusted participation rates prior to the adoption of BIC. The hypothesis that breakfast and lunch participation rates were equal to those in the reference year cannot be rejected, up to seven years prior to BIC adoption. After adoption, participation rates in BIC schools were 7 to 13 percentage points higher in the first year, depending on the extent of BIC coverage, and 14 to 27 percentage points higher in the second year. In schools where BIC was adopted schoolwide, breakfast program participation continued to increase three to four years later. By comparison, the event study analysis for lunch shows no discernible change in participation rates for any year following BIC adoption. (While the estimation sample for Figure 2 was an unbalanced panel, repeating the analysis with a smaller balanced panel of schools produced a nearly identical result.)

Using school-specific linear time trends in the models in Table 2 had only modest effects on these estimated impacts (see the Appendix).24 For example, among all schools, the effects on breakfast participation rates were 2.7, 15.6, and 26.9 percentage points for the three treatment intensities, respectively. All remain statistically significant at the 0.01 level. The negative effect on lunch program participation for middle schools in the second tier of coverage becomes insignificant when school-specific time trends are included.

The Impact of BIC on BMI and Obesity

Estimates of the impact of BIC on student BMI and obesity are shown in Table 3. In this table, the estimated coefficients and standard errors for the three BIC treatment categories are reported (less than 25 percent of classrooms, 25 percent or more of classrooms but not schoolwide, and full BIC). Each panel and column differs in the outcome measure, estimation sample (grades K through 5 or 6 through 8), and specification of the treatment (pre–post indicator for school s, or cumulative days of exposure for student i, measured in hundreds). Impact estimates for z-BMI are shown in panel A, while estimates for the dichotomous obesity outcome are in panel B. Results in later subsections are organized in an analogous manner.

Table 3.

Impact of BIC on obesity and BMI.

| Pre–post

|

Cumulative days

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade K–5 | Grade 6–8 | Grade K–5 | Grade 6–8 | |

| Panel A: impact on z-BMI | ||||

| Post-BIC adoption: school with < 25% coverage | −0.0008 (0.0143) |

−0.0263 (0.0169) |

0.0107* (0.0053) |

0.0080 (0.0045) |

| Post-BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | −0.0045 (0.0159) |

−0.0171 (0.0393) |

−0.0017 (0.0067) |

0.0109 (0.0082) |

| Post-BIC adoption: full school | −0.0164 (0.0304) |

−0.0301 (0.0187) |

−0.0236 (0.0175) |

0.0040 (0.0087) |

| Panel B: impact on obesity | ||||

| Post-BIC adoption: school with < 25% coverage | −0.0013 (0.0037) |

−0.0085 (0.0062) |

0.0029* (0.0014) |

0.0029 (0.0016) |

| Post-BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | 0.0011 (0.0047) |

−0.0100 (0.0154) |

0.0018 (0.0020) |

0.0035 (0.0032) |

| Post-BIC adoption: full school | −0.0023 (0.0086) |

−0.0053 (0.0066) |

−0.0032 (0.0059) |

0.0015 (0.0033) |

| Count of program schools | ||||

| With <25% coverage | 114 | 78 | 114 | 78 |

| With >25% coverage, not full | 55 | 35 | 55 | 35 |

| Full school | 32 | 15 | 32 | 15 |

| Observations | 2,131,469 | 980,088 | 2,131,469 | 980,088 |

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses, robust to clustering at the school level. Obese is defined as being above the 95th percentile nationally for one’s gender and age in months, based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) growth charts. All models include student covariates, grade, school, and year effects. Covariates include age, gender, race/ethnicity, low income status, LEP, immigrant, and special education status. Low income is measured by eligibility for free or reduced price meals or enrollment in a Universal Free Meal school. Age is measured in months at the time of the Fitnessgram. We exclude charter school students, students attending citywide special education schools (District 75), students in schools where Fitnessgram coverage is less than 50 percent, and students with biologically implausible BMIs.

We find no compelling evidence that the offer of BIC increased BMI or the prevalence of obesity in NYC schools. Many of the point estimates in Table 3 are negative, which if taken at face value would indicate that students have lower BMI and lower rates of obesity when their school offers BIC than observationally similar students attending the same schools when not offering BIC. (One notable exception is the cumulative days estimate for K through five students in the weakest BIC category, which is positive and significant at the 0.05 level.) All effect sizes are small and imprecise, however, and we cannot rule out very small positive effects on BMI. Focusing on the difference-in-difference results in the first two columns, the point estimates tend to be largest (in absolute value) for full BIC schools, as would be predicted if a treatment effect were present and were more likely in a school with greater BIC coverage. That said, we cannot reject the hypothesis that the coefficients are the same across the different treatment intensities.

As noted, we experimented with a number of alternative specifications for BIC treatment.25 For example, we set the cumulative days of exposure to zero if the student was not currently in a BIC school; in most cases, these point estimates were smaller in absolute value than those in Table 3. Alternatively, we defined cumulative days of exposure as the number of treated days prior to measurement in year t only, with a separate dummy variable indicating BIC treatment in prior years. The point estimates were again closer to zero than in Table 3. Finally, we estimated separate models for each category of BIC coverage. None of the results were materially different from those in Table 3.

The Impact of BIC on Student Achievement

Table 4 reports our estimates of the impact of BIC on student achievement in ELA and mathematics. As in Table 3, each panel and column reports the estimated coefficients and standard errors for the three treatment categories, with comparable samples and treatment variable definitions. The main difference in Table 3 is that the estimation sample for the elementary school models consists of grades 4 and 5 only, since testing begins in third grade and lagged achievement is included as a covariate.

Table 4.

Impact of BIC on ELA and math achievement.

| Grades 4–5 Pre–post |

Grades 6–8 Pre–post |

Grades 4–5 Cumulative days |

Grades 6–8Cumulative days |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELA | Math | ELA | Math | ELA | Math | ELA | Math | |

| Post-BIC adoption: school with < 25% coverage | −0.004 (0.009) |

−0.004 (0.011) |

0.008 (0.010) |

0.009 (0.013) |

−0.002 (0.003) |

−0.003 (0.004) |

0.001 (0.003) |

0.002 (0.005) |

| Post-BIC adoption: school with > 25% coverage, not full | −0.012 (0.015) |

−0.019 (0.019) |

−0.019 (0.010) |

0.010 (0.017) |

−0.005 (0.004) |

−0.006 (0.005) |

−0.005 (0.003) |

0.007* (0.004) |

| Post-BIC adoption: full school | −0.043 (0.026) |

0.023 (0.037) |

−0.016 (0.019) |

−0.005 (0.034) |

−0.008 (0.009) |

0.013 (0.010) |

−0.006 (0.004) |

0.013 (0.009) |

| Count of program schools | ||||||||

| With <25% coverage | 115 | 114 | 85 | 83 | 115 | 114 | 85 | 83 |

| With >25% coverage, not full | 52 | 52 | 42 | 41 | 52 | 52 | 42 | 41 |

| Full school | 28 | 28 | 16 | 15 | 28 | 28 | 16 | 15 |

| Observations | 717,486 | 744,934 | 1,097,593 | 1,126,258 | 717,486 | 744,934 | 1,097,593 | 1,126,258 |

Notes: Standard errors robust to clustering at the school level shown in parentheses (*P < 0.05). All models include student covariates, grade-by-year, and school effects. Covariates include lagged z-score, gender, race/ethnicity, low income status, LEP, immigrant, and special education status. Low income is measured by eligibility for free or reduced price meals or enrollment in a Universal Free Meal school. Excludes charter school students and students attending citywide special education schools (District 75).

We find no evidence of an impact of BIC on achievement in either subject. Point estimates are again small in absolute value, imprecisely estimated, and vary in sign. The only statistically significant effect we observe is for middle school math, for schools with at least 25 percent of classrooms covered (but not full BIC), a positive 0.007 SD per 100 days (P < 0.05). However, a large sample and multiple models can be expected to produce some statistically significant results. As in Table 3, point estimates for the effect of BIC on achievement tend to be larger in schools with greater BIC coverage, although we cannot reject the hypothesis that the effects are the same across categories. On balance, we see no convincing evidence of an impact of BIC on academic performance. More importantly, all of the point estimates here are considerably smaller than those estimated in Imberman and Kugler (2014) and Dotter (2012). In the concluding section of the paper, we suggest several potential explanations for the divergent findings.

We experimented with the same alternative specifications of the BIC treatment variable for our achievement models as we did for BMI and obesity. In no case were the results materially different (see the Appendix).26 Additionally, because the estimation sample differs for the BMI/obesity and achievement outcomes, we estimated both sets of models with a fixed, identical sample of students with sufficient data to be included in all models.27 Again, the results were qualitatively very similar.

The Impact of BIC on Attendance

Table 5 reports estimates of the impact of BIC on attendance rates, measured as the number of days present as a percent of days enrolled. As in earlier tables, each panel and column reports the estimated treatment effects and standard errors for the three treatment categories, with comparable estimation samples and treatment variable specifications. For attendance, the estimation sample for elementary school includes all grades K through 5 (not just those taking state tests). The middle school sample continues to include grades 6 through 8.

Table 5.

Impact of BIC on attendance.

| Pre–post

|

Cumulative days

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade K–5 | Grade 6–8 | Grade K–5 | Grade 6–8 | |

| Post-BIC adoption: school with < 25% coverage | <0.001 (0.001) |

0.001 (0.001) |

<0.001 (0.001) |

0.001 (0.001) |

| Post-BIC adoption: school with > 25% coverage, not full | 0.001 (0.001) |

0.004 (0.002) |

0.001 (0.001) |

0.001 (0.001) |

| Post-BIC adoption: full school | 0.001 (0.001) |

0.005 (0.003) |

<0.001 (0.001) |

<0.001 (0.001) |

| Count of program schools | ||||

| With <25% coverage | 120 | 86 | 120 | 86 |

| With >25% coverage, not full | 55 | 42 | 55 | 42 |

| Full school | 31 | 15 | 31 | 15 |

| Observations | 2,496,321 | 1,228,769 | 2,496,321 | 1,228,769 |

Notes: Standard errors robust to clustering at the school level shown in parentheses. All models include student covariates, grade, school, and year effects. Covariates include gender, race/ethnicity, low-income status, LEP, immigrant, and special education status. Low income is measured by eligibility for free or reduced-price meals or enrollment in a Universal Free Meal school. Excludes charter school students and students attending citywide special education schools (District 75).

Across models and samples, the estimated effects of BIC on attendance are small and statistically insignificant. The point estimate is never larger than 0.005 (or half a percentage point). In elementary school, attendance rates are already high—about 92 percent in schools that ever adopted BIC—and in middle school about four points lower, on average (88 percent). Assuming a 180-day school year, a 0.50 percentage point increase in attendance translates into 0.9 school days. Thus, the largest point estimate found here—if taken at face value—amounts to about one quarter to less than one full school day a year.

In complementary work (shown in the Appendix), we looked at the potential “socializing effects” of BIC by testing for effects on responses of middle school students to NYC’s School Environment Survey.28 This survey aims to capture student attitudes toward their school, classroom, and teachers, with items such as “I feel welcome in my school,” “Most of the adults I see at school every day know my name or who I am,” “I am safe in my classes,” and so on. We did not find any consistent effects of BIC on responses to any of these survey items.

Student-Level Event Study Models

As we did for school breakfast and lunch participation earlier, we estimated event study regression models for each of the student-level outcomes, school levels, and categories of BIC coverage. The results are shown in Figure 3. For clarity of presentation, this figure shows only the event study coefficients for the intermediate category of BIC program adoption (greater than 25 percent BIC but not full school). (Figures using the other definitions of treatment are similar, and provided in the Appendix.29) Year zero is again the year prior to the student’s school adopting BIC.

As in Figure 2, we see no evidence of a differential trend in math and ELA achievement in BIC schools prior to program adoption. Differences from year zero are small in magnitude and statistically insignificant. The same holds for BMI, obesity, and attendance, especially in grades K through 5. In grades 6 through 8, there is somewhat of an upward trend in BMI and obesity prior to program adoption, which halts after BIC adoption, although differences from year zero are again statistically insignificant. Consistent with our main results in Tables 3 through 5, we find no evidence that BIC significantly affected BMI, achievement, or attendance.

DISCUSSION

BIC has been widely adopted by school districts across the United States, with the goal of increasing SBP participation and ensuring no child starts the school day hungry. Advocates argue moving breakfast from the cafeteria to the classroom will provide myriad other benefits as well, including improved attendance, engagement, and academic performance. One recent study supports the latter claim, finding a substantial impact on math and reading performance (Imberman & Kugler, 2014). Whether these effects represent short-run boosts in test scores or sustained, long-run impacts on academics remains unclear.

At the same time, others have warned that BIC will have deleterious effects on students’ weight, increasing BMI, and obesity, as participants consume more daily calories or less nutritious food than they otherwise would. BIC expansion in NYC was temporarily suspended over this very claim. The evidence base on BIC’s impact on obesity, however, is thin. Our analysis using longitudinal Fitnessgram measures of student BMI indicates these fears are largely unwarranted. We find no evidence BIC increased BMI or the incidence of obesity among students attending schools in New York City offering the program. Nearly all of our point estimates suggest lower average body mass in schools when students are offered BIC, though these effects are small and statistically imprecise, and we cannot rule out very small positive effects. While these estimates are interpreted as “intent-to-treat”—and the treatment was weaker in BIC schools with lower coverage—they are close to zero even in cases where BIC was offered schoolwide.

While there is no evidence of an effect on BMI, our study finds large positive effects of BIC on SBP participation, an effect that did not come at the expense of lower lunch participation. We find no evidence of an impact on reading and math achievement in schools that adopted BIC, suggesting that class time devoted to BIC did not adversely affect achievement and is encouraging. But in no case do our estimates suggest the positive effects found in two of the three prior quasi-experimental studies (all of which were also intent-to-treat). They do, however, align with a recent re-analysis of experimental data showing BIC has small net effects on breakfast consumption and in turn no effect on achievement.

There are a number of reasons why our achievement effects may depart from those in earlier quasi-experimental studies. First, the “first stage” impact of BIC on program participation may have been weaker in NYC than in other settings. Table 2 revealed a substantial increase in SBP take-up in BIC schools, but this increase was smaller than that observed in San Diego (Dotter, 2012). In that study, SBP participation in BIC schools exceeded 90 percent, well above what we observe in NYC.30 As expected, we did not observe as large an impact on schoolwide participation in NYC schools that adopted BIC in a smaller subset of classrooms, which may contribute to our overall null finding on achievement. However, we also found no effects in schools that offered BIC schoolwide, where the impact on participation was much larger. Understanding variability in the effects of BIC on take-up across contexts will be an important question for future research. Second, NYC was already offering free breakfast to students citywide prior to BIC (Leos-Urbel et al., 2013). Dotter (2012) found effects on achievement in San Diego schools, but only in those that did not already offer universal free breakfast. This is consistent with our findings, and may suggest few added benefits of BIC—at least for achievement—beyond those provided by free breakfast.

While our study improves on existing work in a number of ways, it has several limitations. First, a lack of data on classroom-level implementation of the program led us to adopt three relatively broad categories of BIC coverage representing the extent to which BIC is offered in a school. These categories are validated by an increasingly strong relationship with SBP participation postimplementation, but could be improved with classroom- or individual-specific meals data. In ongoing work, we are using newly acquired POS data provided by the NYC Office of School Food to track individual daily student breakfast participation for a subset of schools. Second, the number of schools in NYC that reported schoolwide implementation of BIC was limited to 38. Others offered BIC to a majority of classrooms, however, and we observe large increases in SBP participation in these schools as well. We view the NYC case as relevant to other school districts where the extent of BIC implementation varies across schools. Finally, any potential effects estimated here must be viewed as the net effect of BIC’s direct and indirect impacts (Adolphus, Lawton, & Dye, 2013; Hoyland, Dye, & Lawton 2009). While the net effect is arguably of greatest interest to policymakers, more research will be needed on the mechanisms by which BIC affects students.

Despite these limitations, our study is one of the first to examine the effects of offering BIC on BMI and obesity. It uses annual student-level data on obesity from New York City, the largest school district in the country, where nearly 300 schools adopted BIC by 2011/12 (and roughly 200 schools serving grades K through 8 were used in our models). These data include observations on students as many as four years post-BIC implementation, allowing us to potentially detect longer-run effects. BIC has received considerable scrutiny and media attention in NYC, and school districts nationwide have followed its roll-out closely. Our investigation of the impact of BIC yields evidence of significant increases in SBP participation, with no effect on lunch participation, academic performance, attendance, or BMI. Thus, the modest positive impacts of BIC do not appear to come at the cost of worsening childhood obesity.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Award Number 1R01HD070739 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health. We would like to thank the New York City Department of Education, and especially the Office of School Food, for providing necessary data and support. Stephen O’Brien and Armando Taddei at the Office of School Food and Melissa Pflugh Prescott at NYU have been particularly valuable resources to this project. Siddhartha Aneja, Michele Leardo, and Elizabeth Debraggio provided outstanding research assistance.

APPENDIX

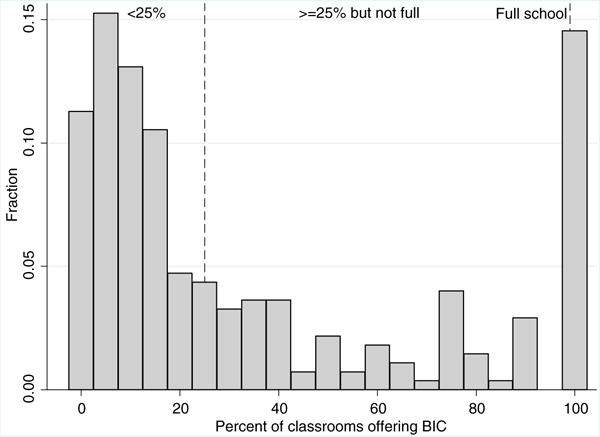

Figure A1. Percent of Classrooms Offering BIC.

Notes: Includes regular public schools serving any of the elementary and middle grades that offered BIC to at least one classroom prior to June 30, 2012 (n = 288). In the few cases where BIC coverage changed over time, we classified schools according to their greatest extent of coverage.

Figure A2. Effect of BIC by Year, Event Study Regressions (Comparable to Figure 3, but Using Full BIC Schools as Treatment).

Note: Baseline year zero is the year prior to BIC adoption.

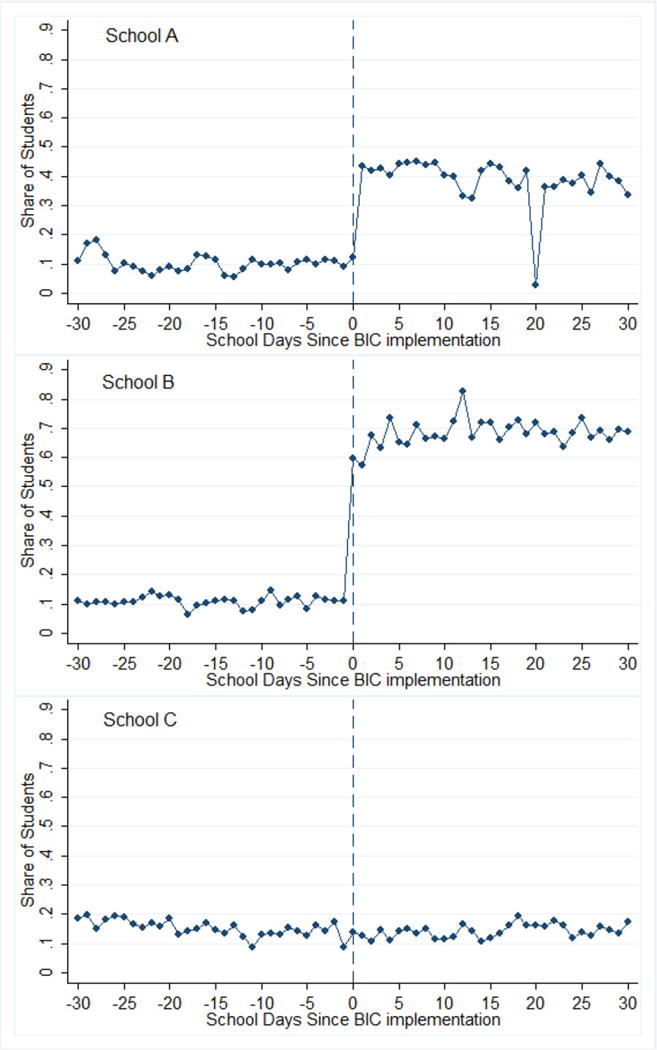

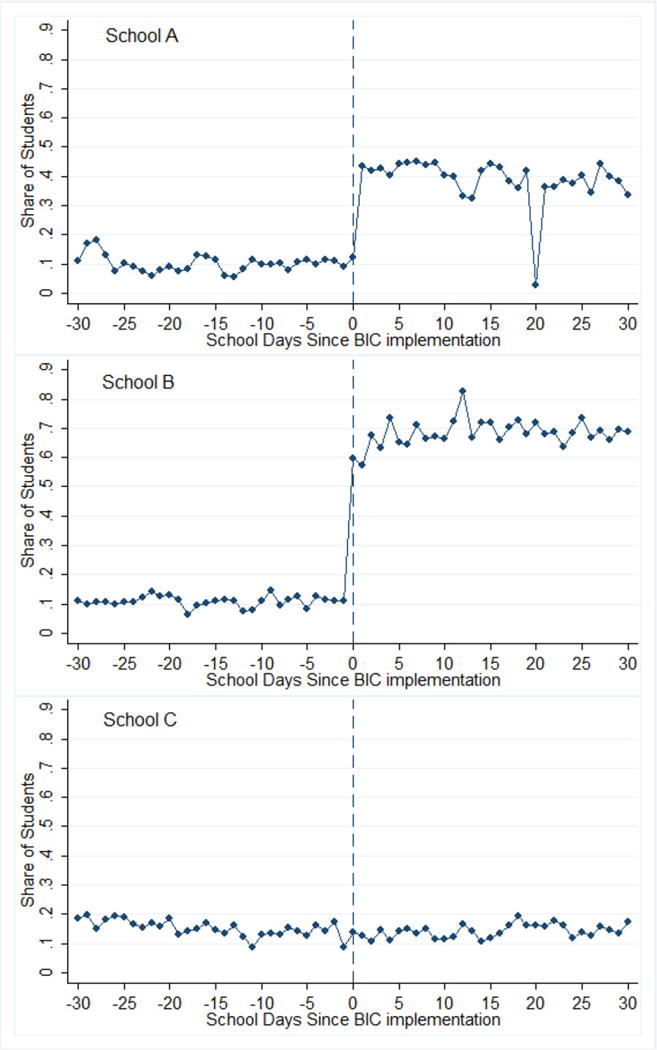

Figure A3. Daily Breakfast Participation before and after BIC Adoption Using Daily POS Data in Three Schools.

Note: See panel B of Table A2 for characteristics of these three schools.

Table A1.

Impact of BIC adoption on meals program participation, 2001/12—Models using school specific linear time trends (compare to Table 2).

| All schools | Elementary | Middle | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breakfast | |||

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | 0.027*** (0.006) |

0.026*** (0.007) |

0.034*** (0.013) |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | 0.156*** (0.019) |

0.168*** (0.022) |

0.152*** (0.043) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | 0.269*** (0.033) |

0.277*** (0.042) |

0.311*** (0.037) |

| Lunch | |||

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | −0.005 (0.007) |

−0.002 (0.006) |

−0.003 (0.018) |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | 0.002 (0.011) |

0.012 (0.010) |

−0.038 (0.021) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | 0.005 (0.020) |

−0.014 (0.023) |

0.041 (0.038) |

| N – breakfast (school × year) | 12,407 | 7,833 | 2,598 |

| Mean breakfast participation pre-2008 | 0.201 | 0.236 | 0.120 |

| N – lunch (school × year) | 12,062 | 7,518 | 2,565 |

| Mean lunch participation 2008 | 0.732 | 0.813 | 0.629 |

Notes: See notes to Table 2 in the paper.

Table A2.

Impact of BIC on daily breakfast participation using daily POS data from three schools.

| School A | School B | School C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Regression discontinuity models | |||

| BIC implementation | 0.36*** (0.02) |

0.53*** (0.02) |

−0.01 (0.01) |

| Daily time trend | 0.00 (0.00) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.00 (0.00) |

| Days post-BIC | −0.01*** (0.01) |

0.00** (0.01) |

0.00** 0.00 |

| Constant | 0.10*** (0.01) |

0.10*** (0.02) |

0.14*** (0.01) |

| N | 19,147 | 10,619 | 23,575 |

| (B) School characteristics | |||

| Percent white | 0.0 | 3.0 | 51.0 |

| Percent black | 33.0 | 17.0 | 14.0 |

| Percent Hispanic | 62.0 | 78.0 | 26.0 |

| Percent free or reduced price meals | 86.0 | 84.0 | 35.0 |

| Percent overweight | 43.6 | 43.8 | 22.9 |

| Percent obese | 17.5 | 24.0 | 12.5 |

| Enrollment | 472 | 259 | 610 |

| UFM school | Y | N | N |

| Borough | Bronx | Bronx | Manhattan |

| Grade range | 5–8 | PK–4 | K–5 |

| BIC implementation date | 12/7/2010 | 2/9/2011 | 1/31/2011 |

| BIC coverage | Full | >25% | >25% |

Notes: Panel (A) shows coefficient estimates from a regression discontinuity model focused on the 20 days before and after the BIC implementation date. The unit of observation is a student-day, and the outcome is a binary variable equal to 1 if the student took a breakfast, taken from point-of-sale transaction data. Each model controls for a daily time trend, day-of-the-week fixed effects, and the number of days after BIC implementation. Standard errors are clustered at the student level. All three of the above schools adopted BIC in 2010/11.

Table A3.

Impact of BIC on ELA and math achievement—models excluding lagged test score.

| Grades 4–5 Pre-post |

Grades 6–8 Pre-post |

Grades 4–5 Cumulative days |

Grades 6–8 Cumulative days |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELA | Math | ELA | Math | ELA | Math | ELA | Math | |

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | 0.0021 (0.0118) |

0.0062 (0.0147) |

0.0082 (0.0152) |

0.0168 (0.0191) |

0.0116** (0.0045) |

0.0107 (0.0055) |

0.0106* (0.0053) |

0.0170* (0.0069) |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | −0.0106 (0.0200) |

−0.0277 (0.0224) |

0.0037 (0.0181) |

0.0067 (0.0270) |

0.0054 (0.0052) |

0.0040 (0.0066) |

0.0082 (0.0042) |

0.0161** (0.0061) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | −0.0126 (0.0351) |

0.0409 (0.0499) |

−0.0190 (0.0283) |

−0.0521 (0.0327) |

0.0081 (0.0131) |

0.0233 (0.0155) |

−0.0017 (0.0060) |

0.0048 (0.0092) |

| Observations | 783,933 | 798,018 | 1,182,336 | 1,204,078 | 783,933 | 798,018 | 1,182,336 | 1,204,078 |

Notes: Compare to Table 4 of the paper. Regression models exclude control for lagged test score.

Table A4a.

Impact of BIC on BMI and obesity—cumulative days set to zero if student’s current school does not offer BIC (compare to Table 3).

| Cumulative days

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Grade K–5 | Grade 6–8 | |

| Panel A: Impact on z-BMI | ||

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | 0.0125 (0.0064) |

0.0026 (0.0064) |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | 0.0012 (0.0086) |

0.0045 (0.0105) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | −0.0275 (0.0193) |

0.0095 (0.0098) |

| Panel B: Impact on obesity | ||

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | 0.0032 (0.0017) |

0.0018 (0.0023) |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | 0.0028 (0.0025) |

0.0002 (0.0039) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | −0.0035 (0.0065) |

0.0040 (0.0032) |

| Observations | 2,131,479 | 980,088 |

Notes: Sets cumulative days to zero if student is not currently offered BIC.

Table A4b.

Impact of BIC on ELA and math achievement—cumulative days set to zero if student’s current school does not offer BIC (compare to Table 4).

| Grades 4–5 Cumulative days |

Grades 6–8 Cumulative days |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELA | Math | ELA | Math | |

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | 0.0023 (0.0035) |

−0.0009 (0.0048) |

0.0024 (0.0041) |

0.0032 (0.0061) |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | −0.0056 (0.0039) |

−0.0051 (0.0051) |

−0.0024 (0.0034) |

0.0121* (0.0047) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | −0.0069 (0.0091) |

0.0133 (0.0105) |

−0.0031 (0.0055) |

0.0085 (0.0127) |

| Observations | 717,486 | 744,934 | 1,097,593 | 1,126,258 |

Notes: Sets cumulative days to zero if student is not currently offered BIC.

Table A4c.

Impact of BIC on attendance—cumulative days set to zero if student’s current school does not offer BIC (compare to Table 5).

| Cumulative days

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Grade K–5 | Grade 6–8 | |

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | 0.0008*** (0.0002) |

0.0009 (0.0005) |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | 0.0009* (0.0004) |

0.0019* (0.0008) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | 0.0008 (0.0005) |

0.0008 (0.0013) |

| Observations | 2,496,321 | 1,228,769 |

Notes: Sets cumulative days to zero if student is not currently offered BIC.

Table A5a.

Impact of BIC on BMI and obesity—cumulative days this year only (compare to Table 3).

| Days this year

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Grade K–5 | Grade 6–8 | |

| Panel A: Impact on z-BMI | ||

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | −0.0001 (0.0002) |

0.0002 (0.0002) |

| Previously in BIC (0, 1) | −0.0028 (0.0134) |

0.0147 (0.0110) |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | 0.0001 (0.0002) |

0.0004 (0.0004) |

| Previously in BIC (0, 1) | −0.0058 (0.0194) |

0.0191 (0.0178) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | −0.0001 (0.0003) |

−0.0005* (0.0002) |

| Previously in BIC (0, 1) | 0.0208 (0.0308) |

−0.0070 (0.0252) |

| Panel B: Impact on obesity | ||

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | −0.0000 (0.0001) |

0.0001 (0.0001) |

| Previously in BIC (0, 1) | −0.0006 (0.0037) |

0.0032 (0.0041) |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | 0.0000 (0.0001) |

0.0001 (0.0001) |

| Previously in BIC (0, 1) | −0.0000 (0.0066) |

0.0076 (0.0072) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | 0.0000 (0.0001) |

−0.0001 (0.0001) |

| Previously in BIC (0, 1) | −0.0037 (0.0107) |

−0.0023 (0.0110) |

| Observations | 2,131,479 | 980,088 |

Notes: Days this year, with a dummy for student previously in BIC.

Table A5b.

Impact of BIC on reading and math achievement—cumulative days this year only (compare to Table 4).

| Grades 4–5 Days this year |

Grades 6–8 Days this year |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELA | Math | ELA | Math | |

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | −0.0000 (0.0001) |

−0.0001 (0.0001) |

0.0001 (0.0001) |

0.0001 (0.0001) |

| Previously in BIC (0, 1) | −0.0262* (0.0127) |

−0.0234 (0.0144) |

−0.0023 (0.0072) |

0.0045 (0.0101) |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | −0.0001 (0.0001) |

−0.0001 (0.0001) |

−0.0001 (0.0001) |

0.0000 (0.0001) |

| Previously in BIC (0, 1) | −0.0099 (0.0178) |

−0.0156 (0.0185) |

−0.0211* (0.0093) |

−0.0134 (0.0105) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | −0.0002 (0.0002) |

0.0003 (0.0003) |

−0.0001 (0.0002) |

−0.0001 (0.0002) |

| Previously in BIC (0, 1) | −0.0095 (0.0256) |

0.0238 (0.0280) |

−0.0199 (0.0165) |

0.0485** (0.0182) |

| Observations | 717,486 | 744,752 | 1,097,593 | 1,125,898 |

Notes: Days this year, with a dummy for student previously in BIC.

Table A5c.

Impact of BIC on attendance—cumulative days this year only (compare to Table 5).

| Days this year

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Grade K–5 | Grade 6–8 | |

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage |

−0.0000 (0.0000) |

0.0000 (0.0000) |

| Previously in BIC (0, 1) | −0.0039*** | 0.0005 |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | (0.0011) 0.0000 |

(0.0013) 0.0000 |

| Previously in BIC (0, 1) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | −0.0083*** (0.0020) |

−0.0045* (0.0021) |

| Previously in BIC (0, 1) | 0.0000 (0.0000) |

0.0000 (0.0000) |

| Previously in BIC (0, 1) | −0.0179*** (0.0030) |

−0.0076* (0.0031) |

| Observations | 2,496,321 | 1,228,769 |

Notes: Days this year, with a dummy for student previously in BIC.

Table A6a.

Impact of BIC on BMI and obesity—cumulative days in 2010 only (compare to Table 3).

| Days this year

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Grade K–5 | Grade 6–8 | |

| Panel A: Impact on z-BMI | ||

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | −0.0004 (0.0008) |

0.0006 (0.0003) |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | 0.0006 (0.0007) |

0.0006 (0.0006) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | 0.0019 (0.0017) |

−0.0006 (0.0018) |

| Panel B: Impact on obesity | ||

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | −0.0001 (0.0002) |

0.0001 (0.0002) |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | 0.0001 (0.0002) |

0.0001 (0.0002) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | 0.0005 (0.0004) |

−0.0002 (0.0006) |

| Observations | 371,111 | 175,697 |

Notes: Uses cumulative days this year only, for the cross section of schools that began BIC in 2010.

Table A6b.

Impact of BIC on reading and math achievement—cumulative days in 2010 only (compare to Table 4).

| Grades 4–5 Days this year |

Grades 6–8 Days this year |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELA | Math | ELA | Math | |

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | −0.0006*** (0.0002) |

−0.0012*** (0.0003) |

−0.0002 (0.0005) |

0.0001 (0.0003) |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | −0.0002 (0.0004) |

−0.0004 (0.0007) |

−0.0005* (0.0002) |

−0.0004 (0.0004) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | −0.0006* (0.0002) |

0.0010** (0.0004) |

−0.0004 (0.0003) |

−0.0006 (0.0004) |

| Observations | 119,025 | 120,607 | 179,503 | 181,926 |

Notes: Uses cumulative days this year only, for the cross section of schools that began BIC in 2010.

Table A6c.

Impact of BIC on attendance—cumulative days in 2010 only (compare to Table 4).

| Days this year

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Grade K–5 | Grade 6–8 | |

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | −0.0001*** (0.0000) |

0.0000 (0.0000) |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | 0.0000 (0.0000) |

−0.0001 (0.0001) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | 0.0001** (0.0000) |

−0.0000 (0.0001) |

| Observations | 397,693 | 193,677 |

Notes: Uses cumulative days this year only, for the cross section of schools that began BIC in 2010.

Table A7a.

Impact of BIC on BMI and obesity—cumulative days in 2010 only, models with school effects and 2007/10 data (compare to Table 3).

| Days this year

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Grade K–5 | Grade 6–8 | |

| Panel A: Impact on z-BMI | ||

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | −0.0004 (0.0008) |

0.0006 (0.0003) |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | 0.0007 (0.0007) |

0.0006 (0.0005) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | −0.0019 (0.0017) |

−0.0007 (0.0018) |

| Panel B: Impact on obesity | ||

| Post BIC adoption: school with <25% coverage | −0.0001 (0.0002) |

0.0002 (0.0002) |

| Post BIC adoption: school with >25% coverage, not full | 0.0001 (0.0002) |

0.0001 (0.0002) |

| Post BIC adoption: full school | 0.0005 (0.0004) |

−0.0002 (0.0006) |

| Observations | 1,304,810 | 590,004 |

Notes: Uses cumulative days this year only, when school began BIC in 2010; includes school fixed effects and 2007/10 data.

Table A7b.