Abstract

In this pilot study of 102 grandmothers raising grandchildren we used a quasi-experimental, repeated measures design to examine effects of resourcefulness training reinforced by expressive writing (journaling) or verbal disclosure (digital voice recording) in reducing stress and depressive symptoms and enhancing quality of life. Resourcefulness training was compared with expressive writing, verbal disclosure, and attention control conditions. Both the expressive writing and verbal disclosure methods for reinforcing resourcefulness training were more effective than the other three conditions in reducing stress and depressive symptoms and improving quality of life; no difference was found between the two reinforcement methods. Thus, grandmothers may benefit from learning resourcefulness skills and practicing them in a way that best fits their needs and lifestyle.

More and more grandmothers are raising grandchildren worldwide (Chen & Liu, 2012). In the United States, the number of grandchildren living with a grandparent has increased 64% over the past 20 years (Kreider & Ellis, 2011). A survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau (2010) found that more than 1.7 million grandmothers provided basic care (food, shelter, and clothing) for their grandchildren, 40% of whom live in their household. The survey also found that close to 70% of the grandmothers were between the ages of 30 and 59 and therefore likely to be in the workforce while also providing care to their grandchild. Maintaining the health of grandmothers raising grandchildren is of critical importance and interventions to address this issue are sorely needed. In this study, we examined an intervention to teach grandmothers resourcefulness skills aimed at reducing their stress and depressive symptoms and enhancing their quality of life.

Health of Grandmothers Raising Grandchildren

Raising a grandchild may be associated with substantial physical, emotional, social, financial, and legal challenges that affect a grandmother’s health and quality of life (Yagoda, 2003). Indeed, many studies have found that grandmothers raising grandchildren are at increased risk for both physical and mental health problems (Musil & Ahmad, 2002; Dowdell, 2005; Grinstead, Leder, Jensen, & Bond, 2003; Whitley, Kelley, & Sipe, 2001). In part, this is because a grandmother may overlook her own health while attending to the physical, psychosocial, and developmental needs of her grandchild (Blustein, Chan, & Guanais, 2004; Davidhizar, Bechtel, & Woodring, 2000; Dowdell, 2004; Landry-Meyer, Gerard & Guzell, 2005). This lack of attention to her own physical and mental health may lead to an inability to continue in this role, which in turn may have negative consequences for the grandchild.

Interventions with Grandmothers

The optimal health and quality of life of grandmothers raising grandchildren may be enhanced with appropriate interventions (Kelley, Whitley, Sipe, & Yorker, 2000; Musil & Ahmad, 2002; Musil, Warner, Zauszniewski, Jeanblanc, & Kercher, 2006; Zauszniewski, Au, & Musil, 2012). However, intervention studies with grandmothers raising grandchildren are few, and most are either purely descriptive, have minimal outcome data, or have small sample sizes (Collins, 2011; Dannison & Smith, 2003; Edwards & Sweeney, 2007; Kelley, Yorker, Whitley, & Sipe, 2001; Kicklighter et al., 2007; Vacha-Haase, Ness, Dannison, & Smith, 2000). Interventions tested have been educational programs (Broome, Dokken, Broome, Woodring, & Stegelman, 2003; Kicklighter et al., 2007), support groups (Collins, 2011; Dannison & Smith, 2003; McCallion, Janicki, & Kolomer, 2004; Robinson, et al., 2000; Smith & Dannison, 2003), or case management (Cohon, Hines, Cooper, Packman, & Siggins, 2003; McCallion, Janicki, Grant-Griffin, & Kolomer, 2000; Robinson, et al., 2000) or used a multimodal approach comprised of parenting skills, financial management, legal services, and other supportive/educational components (Kelley et al., 2001; Kelley, Whitley & Sipe, 2007; Kelley, Whitley, & Campos, 2010; 2013; Vacha-Haase et al., 2000).

Few studies however are focused on improving or maintaining the health of these grandmothers raising grandchildren. Ten studies published since 2000 are focused on grandmothers (Brown et al., 2000; Cohon et al., 2003; Collins, 2011; Cox, 2002; Kelley et al., 2001; 2007; 2010; 2013; Kicklighter et al., 2007; Strozier, Elrod, Beiler, Smith, & Carter, 2004) and four focused on grandparents of both genders (Broome et al., 2003; McCallion et al., 2000; Robinson et al., 2000; Smith & Dannison, 2002). The most common outcome was social support (Collins, 2011; Kelley et al., 2000; 2001; 2007; Robinson et al., 2000; Smith & Dannison, 2002; Strozier et al., 2004).

While some investigators examined health-related outcomes, they did not directly test the effectiveness of the interventions in promoting or maintaining the grandmother’s physical or mental health (i.e., Broome et al., 2003; Brown et al., 2000; Collins, 2011; Kicklighter et al., 2007). For example, Kicklighter and colleagues (2007) evaluated a 10-session educational program to improve nutrition and physical activity in 22 grandparents. The findings showed increased knowledge of healthy nutrition and the benefits of physical activity. However, there was no direct measure to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention on the mental or physical health of grandmothers. Collins (2011) examined the effects of a 4-month faith-based support group in 10 elderly African American grandmothers. Two themes emerged from the analysis that reflected the grandmother’s concerns, including an increased awareness of health risks and a need for occasional respite from the grandchild. However, the effects of the intervention on grandmother’s health were not reported.

Seven intervention studies are focused on physical or mental health outcomes of grandmothers raising grandchildren. Four of the studies were conducted by a research team developed by Kelley using a multi-pronged approach to intervention (Kelley et al., 2001; 2007; 2010; 2013). Their clinical trials tested the use of support groups, home visits, and parenting classes, and their work consistently showed improvement in mental health outcomes, including decreased psychological distress (Kelley et al., 2001) and increased psychological well-being (Kelley et al., 2007; 2010) and health promotion behaviors and attributes (Kelley et al., 2013) in the grandmothers.

In the other three studies of health outcomes of grandmothers, grandfathers were also included (Brown et al., 2000; Cohon et al., 2003; Robinson et al., 2000). In all three, individualized case management was combined with a support group. Robinson and colleagues (2000) examined the effects of a 12-month case management with monthly support groups and found that this blended intervention improved grandparents’ (N=25) mental health. McCallion and colleagues (2000) conducted a 12-month intensive case management program with a 6–8 week bimonthly support group for 103 grandparents raising grandchildren with developmental disabilities. The intervention was effective in decreasing their depressive symptoms. Finally, Cohon and colleagues (2003) tested a 6-month case management and support group intervention with 424 African American grandparents; the findings suggested that the intervention improved the general health of these grandparents.

The six studies focused on the health of grandmothers or both grandmothers and grandfathers all combined individual and support group approaches. While the value of support groups is widely known and appreciated, they also have disadvantages. For example, the priority for a grandmother raising a grandchild is the care/supervision of that child, which may interfere with her ability to attend group sessions. In addition, it is common for grandmothers to be working women, and even when children are in school the grandmothers may not be available to attend a support group. Finally, the support provided by other grandmothers may no longer exist once the sessions are over, leaving grandmothers on their own to manage their health while caring for the grandchildren.

Resourcefulness in Grandmothers

Although resourcefulness training has been found to be beneficial in older adults (Zauszniewski, Eggenschwiler, Preechawong, Roberts, & Morris, 2006a; 2006b), its effectives on the health of grandmothers has not been examined. Resourcefulness is a collection of cognitive and behavioral skills that have been found to promote health and quality of life (Zauszniewski, 2012). Resourcefulness skills are of two types: personal, or self-help skills that are performed independently, and social, or help-seeking skills that are used when self-help skills are either ineffective or inappropriate. Recent findings suggest that teaching grandmothers the personal and social skills that constitute resourcefulness, may be beneficial (Musil et al, 2011; Musil, Warner, Zauszniewski, Wykle, & Standing, 2009).

In this pilot study we examined the effects of a resourcefulness training (RT) intervention on three health outcomes from Zauszniewski’s (2012) theory of Resourcefulness and Quality of Life: perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and quality of life. According to that theory, both personal and social resourcefulness are associated with adaptive health outcomes (e.g., lower stress and fewer depressive symptoms) and quality of life. The individualized, tailored intervention allowed grandmothers to use one of two methods for practicing and reinforcing the skills - - expressive writing (EW) or verbal disclosure (VD). With either method, the grandmothers were able to reflect daily on the resourcefulness skills, whether or not they used them, and how they worked. Because the intervention groups received weekly telephone calls from the research staff, the study design also included an attention only (AO) control condition in which participants received weekly telephone calls but were not taught the resourcefulness skills.

Two research questions were addressed: 1) Do grandmothers who receive RT-EW or RT-VD report lower perceived stress, fewer depressive symptoms, and better quality of life over time than those in comparison groups (EW or VD without RT) and those in an AO condition? and 2) Is one method of reinforcing RT (EW or VD) more effective than the other in reducing perceived stress and depressive symptoms, and improving quality of life in grandmothers raising grandchildren?

Methods

Design

This pilot clinical trial used a quasi-experimental, repeated measures design. The study involved random assignment of grandmothers to one of five treatment conditions to compare the effects of: 1) RT reinforced by expressive writing (EW, journaling); 2) RT reinforced by verbal disclosure (VD, digital voice recording); 3) expressive writing (EW) without RT; 4) verbal disclosure (VD) without RT; and 5) an attention control (AO) condition. Effects on perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and quality of life were examined at baseline (T1) and at 2 (T2), 6 (T3), and 12 (T4) weeks post-intervention.

Sample

This community-based pilot trial involved a convenience sample of 102 grandmothers raising grandchildren. To be included in the study, the grandmother had to have been caring for a grandchild under 18 years of age for at least 6 months. Approval for the protection of human subjects’ was obtained from the University Institutional Review Board. Grandmothers were recruited through flyers posted in the community and distributed at support groups or through referrals made by other grandmothers. Grandmothers who met the study criteria were randomly assigned to one of the five treatment conditions.

Although 126 grandmothers completed baseline (T1) interviews, 10 did not continue because of telephone disconnection, loss of interest, illness, perceived difficulty, or inadequate compensation; 11 withdrew during the intervention phase for similar reasons, including 5 from the RT conditions and 6 from the comparison conditions; 3 withdrew after the intervention but before the second interview. A detailed discussion of reasons for attrition in this sample has been published elsewhere (Zauszniewski et al., 2012).

The final sample of 102 grandmothers included 40 who were randomly assigned to RT, 41 in the comparison conditions of EW or VD without RT, and 21 in the attention only control condition. The sample size was sufficient for examining descriptive statistics, including frequencies, and percentages; for plotting changes in mean scores on perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and quality of life over time; and for conducting repeated measures analyses based on an alpha of .05, power .80 and estimated medium to small effect size of .15 for the three group and two group analyses across four measurement points (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2009).

Interventions

Resourcefulness Training (RT)

The resourcefulness training (RT) intervention was provided for 40 grandmothers. The skills constituting personal and social resourcefulness were taught to the grandmothers by trained interventionists, who were graduate nursing or social work students, during a single 40-minute individual session. Personal resourcefulness skills included self-help strategies such as organizing daily activities, using positive self-statements, positive reframing, exploring new ideas, and changing from one’s usual response to stress. Social resourcefulness skills involved relying on family and friends, exchanging ideas with others, and seeking help from professionals and experts. A laminated 3×5 card that listed the 8 resourcefulness skills was given to each grandmother. The single RT session included an explanation of the resourcefulness skills followed by a discussion of potential situations in which the grandmother might use each skill in her daily activities and in her relationship with her grandchild. After teaching the resourcefulness skills, the interventionist explained the use of the daily written journal (expressive writing), recommending 3–5 pages per day, or daily use of the digital voice recorder (verbal disclosure), recommending 5–7 minutes per day, depending on the condition to which the grandmother was randomly assigned. Journals and recorders were provided for the grandmothers during the 4-week intervention period. Before journaling or recording each day, the grandmothers were asked to review the laminated card to reflect on the resourcefulness skills they had learned. Then, in their journals or recordings, they were to describe their use of the skills for the next 4 weeks, i.e., between the baseline (T1) and second (T2) data collection interviews. This process of reflection on their practice of the resourcefulness skills was expected to reinforce the skills. During the 4 weeks of journaling or recording, weekly reminder telephone calls were made by the interventionist.

Comparison conditions

Because it is known that expressive disclosure, including journaling (expressive writing) and recording (verbal disclosure), helps to reduce negative emotions, manage stress, and improve health and well-being (Lutgendorf & Ulrich, 2002; Pantchenko, Lawson, & Joyce, 2003; Smyth & Helm, 2003;), it was essential to measure its effects without RT. Therefore, 20 grandmothers were randomly assigned to verbal disclosure and 21 to expressive writing. The same number of pages for journaling and minutes for recording as for the RT conditions were recommended. Journals or recorders were provided for the grandmothers’ use during the 4-week intervention period. However, these grandmothers, who were not taught the resourcefulness skills, were asked to write or record daily events, and thoughts and feelings about their day with their grandchild for the 4 weeks between the T1 and T2 data collections. To be consistent with the RT intervention, weekly reminder telephone calls were made to these grandmothers by the interventionist during this 4-week period.

Attention control condition

Twenty-one grandmothers were randomly assigned to an attention control condition. They received weekly telephone calls from a research team member during the 4-week interval between T1 and T2 data collections. During these calls, these grandmothers were reminded about their next data collection appointment and when it would take place.

Instruments

In addition to a demographic questionnaire, we used three quantitative measures to evaluate the effectiveness of the RT intervention. The demographic questionnaire asked for age in years, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, income, and number of health problems identified from a list of 10 common health problems in women, including heart disease, cancer, stroke, respiratory disease, diabetes, hypertension, osteoporosis, kidney disorders, mental disorders, and HIV/AIDS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003).

Perceived stress was measured by the 14-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale from “never” to “very often,” and scores may range from 0 to 56. Higher scores, after reversing scores on 7 items reflecting low stress, indicate greater perceived stress. Internal consistency estimates, as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha, have ranged from .84 to .87 (Cohen et al, 1983; Cohen & Williamson, 1988). Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was .72. Test-retest reliability has been reported, with a correlation of .85 (Cohen et al., 1983; Cohen & Williamson, 1988). Evidence for construct validity comes from predictive relationships with self-assessed health, health service use, health behaviors, help-seeking behavior, and salivary cortisol (Schwartz & Dunphy, 2003; Wright et al., 2004).

Depressive symptoms were measured by the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Items on this scale are rated on a 4-point scale from “rarely” to “always,” and total scores may range from 0 to 60. Higher scores, after reversing scores on four positively worded items, indicate more depressive symptoms. In studies of grandmothers, Cronbach’s alphas have ranged from .88 to .91 (Blustein et al., 2004; Caputo, 2001; Ruiz, Zhu, & Crowther, 2003); the Cronbach’s alpha was .80 in this sample. The CES-D has widely reported validity and has been standardized across populations of various ages and races/ethnicities (Radloff, 1977).

Quality of life was measured by the Short Form 12 (SF-12; Ware, Kosinski, & Keller, 1996), which contains two subscales: psychological well-being (mental health) and physical function (physical health). The simplified scoring method developed by Resnick and Parker (2001) was used; thus, the total score was obtained by summing scores on the 12 items. Four negatively phrased items were reversed scored so that higher scores indicated better overall quality of life. Using this scoring method, the SF-12 was found to have internal consistency reliability in two studies, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .72 to .87 (Resnick & Parker, 2001). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was .90. Test-retest reliability has been reported, with correlations ranging between .73 and .86 after 2–4 weeks, indicating stability of the measure over time (Resnick & Parker, 2001). Construct validity was supported by confirmatory factor analysis, use of contrasted groups, and hypothesis testing (Resnick & Parker, 2001).

Procedures

Quantitative data were collected during four face-to-face, structured interviews with a trained data collector who was blinded to the intervention. The data collection interviews, which were spaced 6 weeks apart, were conducted in a private setting at a mutually agreed-upon time. During the interviews, measures of perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and quality of life were completed. Data from the journals and recorders were retrieved by the interventionist after the 4-week intervention period and before the T2 data collection. The grandmothers were compensated for data collection interviews, and days of journaling or recording were pro-rated. At the end of the study, grandmothers in the comparison and attention control groups were given a laminated card listing the resourcefulness skills and told about the importance of using these skills.

Preliminary analysis of RT

Before testing intervention effectiveness, we examined the need for RT, feasibility of the practice methods used for RT, and RT intervention fidelity in this sample of grandmothers. Detailed descriptions of these analyses are found elsewhere as indicated below and summarized briefly here. Baseline scores on the Resourcefulness Scale (RS) (Zauszniewski, Lai, & Tithiphontumrong, 2006) indicated that 72% of the grandmothers had more than a moderate need for RT; after receiving RT, 88% said they felt they needed the RT and 92% felt that other grandmothers would benefit from learning and practicing the resourcefulness skills (see Zauszniewski et al., 2012).

The two reflection methods used for RT, expressive writing and verbal disclosure, were similar in feasibility. Grandmothers in both conditions (N=40) reported feeling challenged in writing or recording on a daily basis. Although on average, journaling was done on 20/28 days and recording was done on 15/28 days, this difference was not significant; more words were expressed by grandmothers who recorded than those who wrote. Two thirds of the grandmothers in both conditions reported the intervention was acceptable and perceived it as beneficial (see Zauszniewski, Musil, & Au, 2013).

Fidelity of the RT intervention also was examined (Zauszniewski, Musil, Burant, Standing, & Au, in press). We expected that effective teaching and practice of the resourcefulness skills would be reflected in increased RS scores and evident in the journals and recordings. We found that the grandmothers who had RT (journal or recorder) had significantly higher RS scores than those who used a journal or recorder without RT. Yet, the scores did not differ by practice method (journal versus recorder). Moreover, similar use of resourcefulness skills was described in the journals and recordings, though the skills were described more frequently in the recordings, where higher word counts were found in the feasibility analysis (Zauszniewski et al., 2013).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed from the 102 grandmothers in the study; there were no missing data over the four data points (T1–T4). Repeated measures analysis of variance (RMANOVA) was used to examine the effects of RT, comparison conditions, and attention control on measures of perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and quality of life, and to determine whether the effects of RT reinforced by EW differed from those of RT reinforced by VD. Prior to conducting the RMANOVAs, assumptions were tested. Violations to Mauchley’s test of sphericity indicated a need to interpret alternative F statistics as described in the analyses below.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Ages of the 102 grandmothers who took part in the study ranged from 40 to 82 with an average age of 58. Over half of the sample was African American (60%) and almost one third was Caucasian (32%); 2% was Asian; 1% was American Indian and 5% did not report race/ethnicity. Almost one third (30%) were married or cohabitating and nearly another third (30%) reported they were divorced or separated; 19% were single and 21% widowed. One third of the grandmothers (33%) completed high school or GED; 11% reported less than a high school education; 45% completed some college or an associate degree; 11% had a college degree, including 6% with a bachelor’s degree and 5% with a master’s degree. More than half (53%) reported annual incomes less than $20,000 while 28% reported incomes between $20,001 and $40,000; 16% reported income above $40,001; and 3% did not report their income. The grandmothers on average reported having one health condition, with a range of one to six conditions; the most frequently reported were hypertension (43%), diabetes (20%), and mental disorder, i.e. depression (15%). Table 1 shows there were no significant differences found by treatment condition on any of the grandmothers’ characteristics.

Table 1.

Grandmother, caregiving, and grandchild characteristics by treatment condition

| Characteristics | RT Intervention (N = 40 ) | Comparison condition (N = 41) | Attention control (N = 21) | Statistical test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | |

| Age | 57.93 | 10.09 | 57.17 | 8.36 | 61.19 | 9.50 | 1.35 |

| Health problems | 1.23 | 1.50 | 1.17 | 1.26 | 1.52 | 1.33 | 0.50 |

| Years of care | 7.40 | 5.19 | 6.44 | 4.93 | 8.05 | 4.88 | 0.80 |

| Hours per day | 12.15 | 7.43 | 11.34 | 6.30 | 11.33 | 5.96 | 0.18 |

| Age of children | 10.08 | 4.64 | 7.54 | 4.39 | 11.19 | 4.18 | 5.72** |

| Health rating of children | 3.30 | 0.94 | 3.37 | 0.86 | 2.76 | 0.94 | 3.35* |

| Number of children | 1.83 | 0.71 | 1.98 | 1.15 | 1.62 | 0.97 | 0.96 |

|

| |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | χ2 | |

|

| |||||||

| Child gender: | |||||||

| Male | 13 | 32% | 17 | 42% | 9 | 43% | 2.10 |

| Female | 14 | 36% | 12 | 29% | 4 | 19% | |

| Both | 13 | 32% | 12 | 29% | 8 | 38% | |

|

| |||||||

| Race/ethnicity: | |||||||

| White | 18 21 | 46% | 11 27 | 29% | 4 | 19% | 4.74 |

| Nonwhite | 1 | 54% | 3 | 71% | 16 | 81% | |

| Unreporteda | 1 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Marital status: | |||||||

| Married | 10 | 25% | 17 | 42% | 4 | 19% | 4.20 |

| Single/widowed/divorced | 30 | 75% | 24 | 58% | 17 | 81% | |

|

| |||||||

| Education: | |||||||

| Less than high school | 5 | 13% | 2 | 5% | 4 | 19% | 3.76 |

| High school/GED | 13 | 32% | 16 | 39% | 5 | 24% | |

| More than high school | 22 | 55% | 23 | 23% | 12 | 57% | |

|

| |||||||

| Income: | |||||||

| Less than $20,000 | 22 | 58% | 20 | 50% | 12 | 57% | 0.56 |

| $20,001 and more | 16 | 42% | 20 | 50% | 9 | 43% | |

| Unreporteda | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||||

p < .05

p < .01

not in analysis

The grandmothers reported an average of 7 years of caring for their grandchildren and spent an average of 12 hours per day in doing so. They were caring for 1 to 6 grandchildren with 30% raising girls, 38% raising boys, and 32% raising grandchildren of both genders. The grandchildren’s average age was 9 years and, according to the grandmothers, their health averaged a score of 3 (very good) on a 5 point scale that ranged from poor (0) to excellent (4). Table 1 shows there were no significant differences by treatment condition on variables associated with caregiving days or hours or number of children or their gender. However, the groups differed on age and health ratings of the grandchildren with those in the attention control condition being older and less healthy than those in the other treatment conditions (Table 1). However, because the age and health ratings of the grandchildren were not found to be correlated with the study outcomes (perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and quality of life), it was not necessary to control for their effects in the effectiveness analysis (Owen & Froman, 1998).

RT versus Comparison and Control Conditions

We conducted repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) to compare perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and quality of life in grandmothers who received RT (n = 40), those in the comparison groups (n = 41) and those in the attention only control condition (n = 21). We expected that grandmothers who received RT would experience less stress, fewer depressive symptoms, and better quality of life than those in the comparison or control conditions. The effects of the three treatment conditions on perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and quality of life are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Repeated measures analysis for RT effects on perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and quality of life over time

| RQ #1: Analysis of RT, comparison conditions, and attention control | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects | Perceived Stress | Depressive Symptoms | Quality of Life | |||

| df | F | df | F | df | F | |

| Time | 2.82, 278.85 | 6.49a** | 3, 297 | 0.41 | 1.77, 174.94 | 3.13b+ |

| Group | 2, 99 | 12.01** | 2, 99 | 3.09+ | 2, 99 | 4.80* |

| Group × Time | 5.63, 278.85 | 7.84a** | 6, 297 | 2.32+ | 3.53, 174.94 | 3.80b* |

|

| ||||||

| RQ #2: Analysis of RT with expressive writing versus RT with verbal disclosure | ||||||

| Effects | Perceived Stress | Depressive Symptoms | Quality of Life | |||

| df | F | df | F | df | F | |

| Time | 3, 114 | 20.40** | 3, 114 | 3.85* | 1.76, 66.78 | 9.28b** |

| Group | 1, 38 | 0.01 | 1, 38 | 0.01 | 1, 38 | 0.10 |

| Group × Time | 3, 114 | 0.15 | 3, 114 | 0.20 | 1.76, 66.78 | 0.05b |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Huynh-Feldt correction

Greenhouse-Geisser correction

Mean scores on perceived stress varied significantly over the four time points and a significant time × group interaction effect was found, indicating changes within the groups over time. Degrees of freedom were adjusted using the Greenhouse-Geisser epsilon (true experimental error = .893) because of violation of Mauchley’s test of sphericity. Because this value exceeded .75, the Huynh-Feldt adjustment was made (Girden, 1992). The test of between-subjects effects was also significant. Post hoc analysis revealed that grandmothers in the RT groups (EW and VD) reported lower stress over time than those in the comparison (EW and VD) conditions and those in the attention only control condition. Mean scores for the three groups over the four measurement points are plotted over time in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mean scores on Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) over time

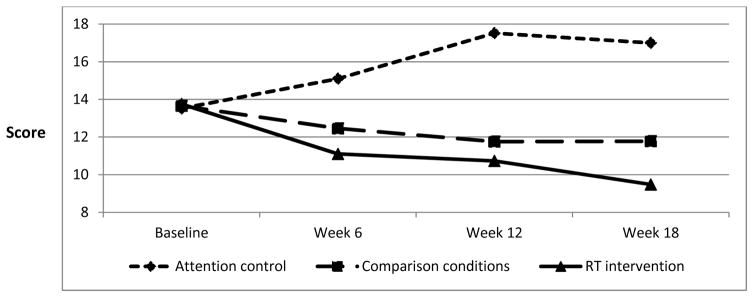

The next analysis involved examination of depressive symptoms to determine whether grandmothers who received RT reported fewer depressive symptoms over time than those who participated in the comparison or control conditions. Although mean scores appeared to suggest downward trends toward fewer depressive symptoms in the RT condition and, to a lesser degree, in the comparison condition, no significant effect of time was found in the tests of within-subjects effects. However, a significant time × group interaction effect was found, indicating changes within the groups over time. The test of between-subjects effects was also significant. Post hoc analysis revealed that grandmothers in the RT conditions (EW and VD) reported fewer depressive symptoms over time than those in the comparison (EW and VD) conditions and those in the attention only control condition. Mean scores for the three groups over the four measurement points are plotted over time in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mean scores on Center for Epidemiological Studies - Depression Scale (CES-D) over time

A third RM-ANOVA focused on whether grandmothers who received RT reported better quality of life than those in the comparison and control conditions. Mean scores on quality of life over time suggested an increasing trend toward better quality of life for grandmothers who received RT. The tests of within subjects effects were significant for the effect of time and a significant group × time interaction effect was found. Degrees of freedom were adjusted for these analyses using the Greenhouse-Geisser epsilon (true experimental error = .589) because of violation of Mauchley’s test of sphericity. The test of between-subjects effects was also significant. Post hoc analysis revealed that grandmothers in the RT groups (EW and VD) reported better quality of life over time than those in the comparison (EW and VD) conditions and those in the attention only control condition. Mean scores for the three groups over the four measurement points are plotted over time in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Mean scores on Short Form – 12 (SF-12) over time

RT-EW versus RT-VD

We conducted RM-ANOVA to compare perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and quality of life in grandmothers who received RT with EW and those who received RT with VD. There were 20 grandmothers in each of these two conditions. Our aim was to determine whether the two methods of reinforcing resourcefulness skills had similar effects on the study outcomes. Although the literature on expressive disclosure suggests that EW is more beneficial than VD in reducing stress (Pennebaker, 2003), there is no literature on differences in depressive symptom or quality of life outcomes between the two reinforcement methods.

The mean scores on perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and quality of life varied significantly over the four time points. Perceived stress and depressive symptoms decreased over time while quality of life improved. However, for the analysis for quality of life, degrees of freedom were adjusted using the Greenhouse-Geisser epsilon (true experimental error = .586) because of violation of Mauchley’s test of sphericity. We found no significant differences between grandmothers who received RT with EW and those who received RT with VD on perceived stress, depressive symptoms, or quality of life. The interaction between group and time for those three outcomes was also not significant. Mean scores on perceived stress, depressive symptoms, and quality of life for the two groups at the four measurement points are shown in Table 2.

Discussion

We compared the effects of resourcefulness training (RT) with reinforcement through expressive disclosure (i.e. expressive writing, [EW], or verbal disclosure, [VD]), with expressive disclosure alone (without RT) and an attention control group. In general, RT was more effective than the two expressive disclosure comparison conditions and the attention control condition in reducing perceived stress and depressive symptoms and enhancing quality of life. The findings are consistent with resourcefulness theory, which suggests that personal and social resourcefulness are associated with process regulators involving affective and cognitive components, such as stress, and indicators of quality of life (Zauszniewski, 2012). Although the interventions tested in previous studies with grandmothers differed from RT, our findings are similar to those reported in a series of studies by Kelley and colleagues (Kelley et al., 2001; 2007; 2010; 2013) that found decreased psychological distress, increased psychological well-being, and improved health promotion behaviors in grandmothers.

The comparative analysis of treatment effects on perceived stress showed decreasing trends for the RT and comparison conditions with the RT effects much stronger. Previous research on expressive disclosure using self-reflection methods such as journaling (expressive writing) and recording (verbal disclosure), has shown that both methods can reduce stress and improve psychological well-being (Lutgendorf & Ulrich, 2002; Smyth & Helm, 2003; Pantchenko et al., 2003); our findings in regard to the comparison conditions are consistent with these findings. However, we found that teaching resourcefulness skills and using emotional disclosure methods for practice and reinforcement of the skills resulted in even stronger stress-reducing effects. Thus, the grandmother’s self-reflection on use of resourcefulness skills made a difference that exceeded the cathartic effect achieved through emotional disclosure alone.

Similar to the effects for perceived stress, the RT condition showed substantial decreases in depressive symptoms while the comparison conditions showed a slight but insignificant decrease and the attention control condition showed an increase in symptoms. While an interpretation similar to the one described above with perceived stress may exist for the RT and comparison conditions, the spike in depressive symptoms in the attention control condition, from a baseline score of 13.5 to 17, higher than the CES-D “cut-off” of 16, was not expected and may reflect an increased likelihood of clinical depression (Radloff, 1997). The increases in perceived stress and depressive symptoms in the attention control condition may reflect actual escalations in their distress over time, or they may represent reactivity to the fact that they were being studied but not receiving any intervention (Frey, 2010).

The quality of life measure remained stable for the comparison and attention control conditions, but improved for the RT condition. Thus, as is consistent with the theory of resourcefulness and quality of life (Zauszniewski, 2012), resourcefulness skills appear to have a positive influence on health appraisal and activity performance. There was no significant difference between the two self-reflection, practice methods for RT (journal or recorder) on the three outcomes. Both showed significant improvements over time, suggesting the possibility of providing a choice between the two methods for the grandmothers. Although previous research has shown that for RT in its present form, using either self-reflection method is feasible and acceptable (Zauszniewski et al., 2013), providing a choice between practice methods may enhance the sustainability of the RT over time.

Despite the encouraging results of the RT intervention, there were several limitations to this study. Grandmothers were recruited only from northeastern Ohio, and were primarily White and African American; the RT also needs to be tested with other samples, such as Hispanic or Asian grandmothers. In addition, the sample was fairly well educated; it is unknown whether less educated persons would be able to learn and apply the resourcefulness skills in the same way. Although the effectiveness of the RT intervention in reducing stress, and depressive symptoms and improving quality of life was supported, the EW and VD subgroup analyses may have been underpowered due to the small sample sizes. Additional comparisons, perhaps expanding on self-report data to include additional psychological and physiological outcome measures, are recommended. The design of the study required repeated use of the same outcome measures within a short time period (4 times in 24 weeks), which may have affected subsequent measures over time; however, if such effects occurred, they would have had similar effects across the treatment conditions.

Despite the study limitations, the RT intervention shows great promise for improving the health and well-being for grandmothers raising grandchildren. Previous research shows that grandmothers perceive a need for learning resourcefulness skills (Zauszniewski et al, 2012) and that the RT intervention is acceptable and feasible for the grandmothers (Zauszniewski et al, 2013). This individualized, tailored intervention is grounded in principles of adult learning and follows the philosophy that merely teaching skills is insufficient; intervention recipients must practice and use the skills to reinforce the learning and to incorporate them within their own personal repertoire of skills for coping, adaptation, and health promotion. RT involves a minimal investment of time and resources and may therefore be cost-effective. The RT intervention can be made available for grandmothers through various venues within the community, including senior centers and, health clinics. However, further research to examine the beneficial effects of RT within a randomized clinical trial with a larger, more diverse sample of grandmothers is recommended, and the impact of allowing grandmothers to choose a reinforcement method and other alternative methods for practicing and reinforcing the resourcefulness skills should be explored.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research (R21-NR-010581) awarded to Dr. Jaclene A. Zauszniewski.

The authors acknowledge the editorial assistance of Elizabeth M. Tornquist of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Contributor Information

Jaclene A. Zauszniewski, Kate Hanna Harvey Professor of Community Health Nursing.

Carol M. Musil, Professor of Nursing.

Christopher J. Burant, Assistant Professor of Nursing.

Tsay-yi Au, Project Coordinator.

References

- Blustein J, Chan S, Guanais FC. Elevated depressive symptoms among caregiving grandparents. Health Services Research. 2004;39:1671–1690. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00312.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broome ME, Dokken DL, Broome CD, Woodring B, Stegelman MF. A study of parent/grandparent education for managing a febrile illness using the CALM approach. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2003;17:176–183. doi: 10.1067/mph.2003.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Jemmott LS, Outlaw FH, Wilson G, Howard M, Curtis S. African American grandmothers’ perceptions of caregiver concerns associated with rearing adolescent grandchildren. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2000;14:73–80. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9417(00)80022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo RK. Depression and health among grandmothers co-residing with grandchildren in two cohorts of women. Families in Society. 2001;82:473–483. doi: 10.1606/1044-3894.166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Liu G. The health implications of grandparents for grandchildren in China. Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological and Social Sciences. 2012;67B:99–112. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The social psychology of health. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cohon D, Hines L, Cooper B, Packman W, Siggins E. A preliminary study of an intervention with kin caregivers. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships. 2003;1:49–72. doi: 10.1300/J194v01n03_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WL. A strengths-based support group to empower African American grandmothers raising grandchildren. Social Work & Christianity. 2011;38:453–466. [Google Scholar]

- Cox CB. Empowering African American custodial grandparents. Social Work. 2002;47:45–54. doi: 10.1093/sw/47.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannison L, Smith A. Lessons learned from a custodial grandparent community support program. Children and Schools. 2003;25:87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Davidhizar R, Bechtel G, Woodring B. The changing role of grandparenthood. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2000;26:24–29. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20000101-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdell EB. Grandmother caregivers and caregiver burden. American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2004;29(5):299–304. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200409000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdell EB. Grandmother caregiver reactions to caring for high-risk grandchildren. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2005;31(6):31–37. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20050601-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards OW, Sweeney AE. Theory-based interventions for school children cared for by their grandparents. Educational Psychology in Practice. 2007;23:177–190. doi: 10.1080/02667360701320879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavioral Research Methods. 2009;41:1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey B. Reactive arrangements. In: Salkind NJ, editor. Encyclopedia of research design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2010. pp. 1224–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Girden ER. ANOVA: Repeated measures. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1992. p. 84. Sage University Papers Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Grinstead LN, Leder S, Jensen S, Bond L. Review of research on the health of caregiving grandparents. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003;44:318–326. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SJ, Whitley DM, Campos PE. Grandmothers raising grandchildren: Results of an intervention to improve health outcomes. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2010;42:379–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SJ, Whitley DM, Campos PE. African American caregiving grandmothers: Results of an intervention to improve health indicators and health promotion behaviors. Journal of Family Nursing. 2013;19:53–73. doi: 10.1177/1074840712462135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SJ, Whitley DM, Sipe TA. Results of an interdisciplinary intervention to improve the psychosocial well-being and physical functioning of African American grandmothers raising grandchildren. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships. 2007;5:45–64. doi: 10.1300/J194v05n03_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley S, Whitley D, Sipe T, Yorker B. Psychological distress in grandmother kinship care providers: The role of resources, social support, and physical health. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24:311–321. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley S, Yorker B, Whitley D, Sipe T. A multimodal intervention for grandparents raising grandchildren: Results of an exploratory study. Child Welfare. 2001;80:27–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kicklighter JR, Whitley DM, Kelley SJ, Shipskie SM, Taube JL, Berry RC. Grandparents raising grandchildren: A response to a nutrition and physical activity intervention. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007;107:1210–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreider RM, Ellis R. Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2011. Living arrangements of children: 2009; pp. 70–126. [Google Scholar]

- Landry-Meyer L, Gerard JM, Guzell JR. Caregiver stress among grandparents raising grandchildren: The functional role of social support. Marriage and Family Review. 2005;37:171–190. doi: 10.1300/J002v37n01_11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lutgendorf SK, Ullrich P. Cognitive processing, disclosure, and health: Psychological and physiological mechanisms. In: Lepore SJ, Smyth JM, editors. The writing cure: How expressive writing promotes health and emotional well-being. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- McCallion P, Janicki MP, Grant-Griffin L, Kolomer SR. Grandparent caregivers: Service needs and service provision issues. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2000;33:57–84. doi: 10.1300/J083v33n03_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCallion P, Janicki MP, Kolomer SR. Controlled evaluation of support groups for grandparent caregivers of children with disabilities and delays. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 2004;109:352–361. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109<352:CEOSGF>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musil C, Ahmad M. Health of grandmothers: A comparison by caregiver status. Journal of Aging and Health. 2002;14:96–121. doi: 10.1177/089826430201400106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musil C, Gordon NL, Warner CB, Zauszniewski JA, Standing T, Wykle M. Grandmothers and caregiving to grandchildren: Continuity, change, and outcomes over 24 months. The Gerontologist. 2011;51:86–100. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musil CM, Warner CB, Zauszniewski JA, Jeanblanc A, Kercher K. Grandmothers, caregiving, and family functioning. Journal of Gerontology. 2006;61:S89–S98. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.2.s89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musil CM, Warner CB, Zauszniewski JA, Wykle ML, Standing TS. Grandmother caregiving, family stress and strain, and depressive symptoms. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2009;31:389–408. doi: 10.1177/0193945908328262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen SV, Froman RD. Uses and abuses of the analysis of covariance. Research in Nursing and Health. 1998;21:557–562. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199812)21:6<557::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantchenko T, Lawson M, Joyce MR. Verbal and non-verbal disclosure of recalled negative experiences: Relation to well-being. Psychology & Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice. 2003;76:251–265. doi: 10.1348/147608303322362488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. The social, linguistic, and health consequences of emotional disclosure. In: Suls J, Wallston KA, editors. Social psychological foundations of health and illness. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers; 2003. pp. 288–313. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1997;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick B, Parker R. Simplified scoring and psychometrics of the revised 12-item Short Form Health Survey. Outcomes Management for Nursing Practice. 2001;5(4):161–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MM, Kropf NP, Myers LL. Grandparents raising grandchildren in rural communities. Journal of Mental Health and Aging. 2000;6:353–365. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz D, Zhu C, Crowther M. Not on their own again: Psychological, social, and health characteristics of custodial African American grandmothers. Journal of Women and Aging. 2003;15(2/3):167–184. doi: 10.1300/J074v15n02_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz KA, Dunphy G. An examination of perceived stress in family caregivers of older adults with heart failure. Experimental Aging Research. 2003;29:221–235. doi: 10.1080/03610730303717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Dannison L. Educating educators: Programming to support grandparent-headed families. Contemporary Education. 2002;72:47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Dannison L. Grandparent-headed families in the United States: Programming to meet unique needs. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships. 2003;1:35–47. doi: 10.1300/J194v01n03_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth J, Helm R. Focused expressive writing as self-help for stress and trauma. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59:227–235. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strozier AL, Elrod B, Beiler P, Smith A, Carter K. Developing a network of support for relative caregivers. Children and Youth Services Review. 2004;26:641–656. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey: Current Population, “Table 3: Employment Status of the Civilian Noninstitutional Population by Age, Sex, and Race,” Annual Averages 2010. Washington, DC: Author; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Women’s Health USA 2003. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vacha-Haase T, Ness CM, Dannison L, Smith A. Grandparents raising grandchildren: A psychoeducational group approach. Journal for Specialists in Group Work. 2000;25:67–78. doi: 10.1080/01933920008411452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley DM, Kelley SJ, Sipe TA. Grandmothers raising grandchildren: Are they at increased risk of health problems? Health & Social Work. 2001;26:105–114. doi: 10.1093/hsw/26.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright RJ, Finn P, Contreras JP, Cohen S, Wright RO, Staudenmayer J, … Gold DR. Chronic caregiver stress and Ige expression, allergen-induced proliferation, and cytokine profiles in a birth cohort predisposed to atopy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2004;113:1051–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagoda L. Grandparent-headed households: Implications for the older adult. National Association of Social Workers. 2003;3 Retrieved from https://www.naswdc.org/login.asp?ms=restr&ref=/practice/aging/Aging-PU_0403.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA. Resourcefulness. In: Fitzpatrick JJ, Kazer M, editors. Encyclopedia of nursing research. New York, NY: Springer Publishing; 2012. pp. 448–449. [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA, Au TY, Musil CM. Resourcefulness training for grandmothers raising grandchildren: Is there a need? Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2012;33:680–686. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.684424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA, Eggenschwiler K, Preechawong S, Roberts BL, Morris DL. Effects of teaching resourcefulness skills in elders. Aging and Mental Health. 2006a;10:404–412. doi: 10.1080/13607860600638446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA, Eggenschwiler K, Preechawong S, Roberts BL, Morris DL. Effects of teaching resourcefulness and acceptance on affect, behavior, and cognition of chronically ill elders. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2006b;28:575–592. doi: 10.1080/01612840701354547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA, Lai CY, Tithiphontumrong S. Development and testing of the Resourcefulness Scale for older adults. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2006;14:57–68. doi: 10.1891/jnum.14.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA, Musil CM, Au TY. Resourcefulness training for grandmothers raising grandchildren: Acceptability and feasibility of two methods. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2013;34:435–441. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.758208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauszniewski JA, Musil CM, Burant CJ, Standing TS, Au TY. Resourcefulness training for grandmothers raising grandchildren: Establishing fidelity. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0193945913500725. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]